Abstract

Neonatal whisker trimming followed by adult whisker regrowth leads to higher responsiveness and altered receptive field properties of cortical neurons in corresponding layer 4 barrels. Studies of functional thalamocortical (TC) connectivity in normally reared adult rats have provided insights into how experience-dependent TC synaptic plasticity could impact the establishment of feedforward excitatory and inhibitory receptive fields. The present study employed cross-correlation analyses to investigate lasting effects of neonatal whisker trimming on functional connections between simultaneously recorded thalamic neurons and regular-spike (RS), presumed excitatory, and fast-spike (FS), presumed inhibitory, barrel neurons. We find that, as reported previously, RS and FS cells in whisker-trimmed animals fire more during the earliest phase of their whisker-evoked responses, corresponding to the arrival of TC inputs, despite a lack of change or even a slight decrease in the firing of thalamic cells that contact them. Functional connections from thalamus to cortex are stronger. The probability of finding TC-RS connections was twofold greater in trimmed animals and similar to the frequency of TC-FS connections in control and trimmed animals, the latter being unaffected by whisker trimming. Unlike control cases, trimmed RS units are more likely to receive inputs from TC units (TCUs) and have mismatched angular tuning and even weakly responsive TCUs make strong functional connections on them. Results indicate that developmentally appropriate tactile experience early in life promotes the differential thalamic engagement of excitatory and inhibitory cortical neurons that underlies normal barrel function.

Keywords: barrel, somatosensory system, experience-dependent plasticity, development

sensory experience affects the development of thalamocortical (TC) circuitry. Pioneering studies in the visual system of cats and monkeys demonstrated substantial alterations in the termination of geniculocortical axons in layer 4 of primary visual cortex and/or of receptive field properties of layer 4 neurons consequent to monocular eye closure (Hubel et al. 1977; Wiesel and Hubel 1963). Effects are age dependent and extend well into adulthood after normal vision is restored, often remaining permanent. In the rodent somatosensory system, damage to primary afferent neurons innervating the whiskers results in permanent alterations in the anatomical pattern of whisker-related cortical layer 4 barrels provided that the peripheral damage is produced within the first few days of postnatal life (Van der Loos and Woolsey 1973). Simply trimming whiskers early in life has no effect on the gross morphology of corresponding cortical barrels but does lead to abnormalities in somatosensory cortical function and whisker-based tactile discrimination (Carvell and Simons 1996; Hand 1982; Rema et al. 2003; Simons and Land 1987). In adult animals whisker trimming immediately reduces afferent activity (Durham and Woolsey 1978; Kelly et al. 1999), although it is unclear how this affects long-term activity in young animals. Simons and Land first reported that neonatal whisker trimming followed by 3–15 wk of regrowth during adulthood leads to increased responsiveness of cortical barrel neurons that can be observed even months after whiskers fully regrow. Such increased responsiveness is not observed in layer 4 barrels when plucked whiskers are allowed to regrow for only a few days (Fox 1992). Neonatal whisker trimming followed by regrowth is associated with abnormal inhibitory as well as excitatory barrel neuron receptive fields (Shoykhet et al. 2005). During normal development whisker-evoked responses of thalamic and cortical neurons remain immature for many weeks after birth during a time when TC synapses continue to mature (Shoykhet and Simons 2008). Correspondingly, similar though less robust functional effects can be produced when whisker trimming is delayed until the beginning of the third postnatal week (Shoykhet et al. 2005).

A number of studies have shown a variety of robust changes in barrel interneurons after neonatal whisker trimming or whisker plucking without subsequent regrowth. These abnormalities include a decreased number of GABA-immunoreactive neurons (Micheva and Beaulieu 1995a, 1995b), diminished parvalbumin (PV)-positive expression and GAD-positive varicosities (Jiao et al. 2006), fewer symmetric synapses (Sadaka et al. 2003), and smaller-amplitude miniature inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (Jiao et al. 2006). Jiao et al. observed an overall 1.5-fold reduction in the size of evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in spiny stellate cells. Intrinsic properties of PV-positive cells are also altered by whisker trimming, rendering them less excitable (Sun 2009). Interpretation of changes in inhibitory barrel circuitry is often complicated by the experimental approach, in some cases necessitated by the use of in vitro slices, in which barrels are examined in relatively young animals before whiskers are allowed to regrow fully. It is thus difficult to disambiguate long-term developmental changes from use-dependent phenomena that can be observed in adult animals when whiskers are prevented from regrowing to normal lengths (Welker et al. 1989). On the other hand, after neonatal whisker trimming and prolonged regrowth there is an absence of activity-related effects on GAD staining when whiskers are retrimmed in adulthood (Akhtar and Land 1991; Land et al. 1995). Differences in experimental design notwithstanding, available evidence is nevertheless consistent with the view that early whisker trimming produces a potentially wide range of abnormalities in local inhibitory barrel circuitry, some of which may persist well after whiskers regrow in adulthood (e.g., Chattopadhyaya et al. 2004).

Whisker trimming followed by adult regrowth leads to larger responses in barrel neurons that are observed as early as the first 1 or 2 ms of the whisker-evoked response (Lee et al. 2007; Simons and Land 1987), corresponding to the arrival time of TC signals (Bruno et al. 2003). Based on this observation Simons and Land proposed that trimming-induced effects reflect “increased or more efficient input” from the thalamus accompanied by diminished intracortical inhibition. Subsequent in vitro studies described a number of mechanisms underlying TC synapse development and experience-dependent modulation (for a review see Inan and Crair 2007), including differential TC engagement of inhibitory vs. excitatory barrel neurons (Chittajallu and Isaac 2010; Daw et al. 2007).

Here we employed simultaneous recordings of thalamic and cortical spike trains to examine changes in TC functional connectivity consequent to neonatal whisker trimming followed by whisker regrowth in adulthood. Cross-correlation approaches have provided key insights into how responses of cortical layer 4 neurons reflect those of thalamic cells that contact them (e.g., Alonso and Swadlow 2005; Bruno and Simons 2002; Johnson and Alloway 1996; Reid and Alonso 1995; Roy and Alloway 2001; Swadlow and Gusev 2002). Findings from these and closely related studies using a variety of experimental approaches (see discussion) point to the potential consequences of developmentally regulated TC synaptic plasticity in the establishment of feedforward excitatory and inhibitory cortical receptive fields. We find that functional connections between thalamic cells and regular-spike (RS) barrel neurons, presumed excitatory cells, are twofold more likely and less response selective than in control animals, rendering RS cells similar to fast-spike (FS) cells, presumed inhibitory neurons, in barrels of control and whisker-trimmed rats. Findings indicate that tactile experience early in life regulates the differential engagement of excitatory and inhibitory barrel neurons that underlies normal adult barrel function.

METHODS

Animals.

All procedures using rats were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rat pups were obtained from pregnant dams (Sprague-Dawley strain; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). Pups, both male and female, were randomly assigned to two groups. One group, denoted “trimmed,” had all whiskers on the left face trimmed until 30 days after birth; trimming was done daily until 2 wk of age and then every other day thereafter. Whiskers were trimmed with irridectomy scissors, with care taken to cut only the whiskers, not the common fur. Rats were held gently without general anesthesia. The second group were handled similarly, but their whiskers were trimmed only once, at 30 days after birth; these animals are denoted “control.” Rats (5 control, 10 trimmed) were coded with tail markings so that recording experiments and initial analyses, i.e., spike sorting, were performed blindly by the experimenters. Median regrowth periods of 61 days (range: 35–115), comparable to previous studies (Shoykhet et al. 2005; Simons and Land 1987), did not differ between control and trimmed groups. A third group of animals (n = 3), studied in pilot experiments, were normally reared without any whisker trimming. Because data from these animals were similar to those from control animals and to data from previous studies in our laboratory, they were combined with data from the control group (total, n = 8 control animals). There were no differences in the relative proportions of male and female rats in trimmed and control groups, nor were there sex-related differences in connectivity.

Electrophysiological recordings.

Unit recordings were obtained from animals prepared as described previously (Bruno and Simons 2002). Rats were anesthetized with 1.5–2.0% isoflurane vapors in 50% O2-N2 and fitted with a tracheal cannula for artificial ventilation and venous and arterial cannulas for drug delivery and blood pressure/heart rate monitoring. Skull screws were used for electroencephalography. Small craniotomies were made overlying the right barrel cortex and ventral posterior medial thalamus (VPm). The animal's head was held by a steel post fixed to the skull with dental acrylic, and the animal was warmed with a servo-controlled heating blanket. After all surgical procedures isoflurane was discontinued, and during subsequent unit recordings rats were narcotized with fentanyl (∼10 μg·kg−1·h−1 iv). To prevent spontaneous whisker movements that would interfere with our whisker stimulators, animals were immobilized with pancuronium bromide (1.6 mg·kg−1·h−1) and artificially ventilated with a positive-pressure respirator. The condition of the animal was monitored continuously with a computer program that assessed electroencephalogram, heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure, and the tracheal airway pressure waveform. Experiments were terminated if normative physiological values could not be maintained; this occurred only rarely. At the end of the recording session, rats were killed with pentobarbital sodium (>100 mg/kg iv) and perfused for cytochrome oxidase (CO) histochemistry. The right cortical hemisphere was removed from the rest of the brain and sectioned tangentially, reacted for CO and horseradish peroxidase (HRP), and stained with Nissl. The diencephalon was cut in the coronal plane and stained similarly.

Extracellular unit recordings were obtained simultaneously from neurons in VPm and layer 4 cortical barrel field corresponding to contralateral facial whiskers. Thalamocortical units (TCUs) were recorded with insulated stainless steel or tungsten microelectrodes having impedances of 1–3 MΩ at 1,000 Hz. Recordings of cortical units were obtained with glass micropipettes (3–6 MΩ) filled with 3 M NaCl or HRP (10% wt/vol) for marking selected sites. After initial physiological mapping thalamic and cortical electrodes were advanced into topographically corresponding locations in VPm and cortical layer 4, the latter corresponding to microdrive readings from 700 to 1,000 μm below the pial surface. Data were collected from units having the same principal whisker (PW) defined as the vibrissa clearly evoking the most robust response from nearby neurons. Histological evaluation confirmed that cortical recordings were obtained from anatomically corresponding CO-dense barrel centers or from the barrel sides or immediately adjacent septa; in this preparation, firing properties and functional TC connectivity are similar among barrel center and nearby cells (Bruno and Simons 2002). Thalamic recordings were verified as being within VPm. Standard amplification and filtering were used.

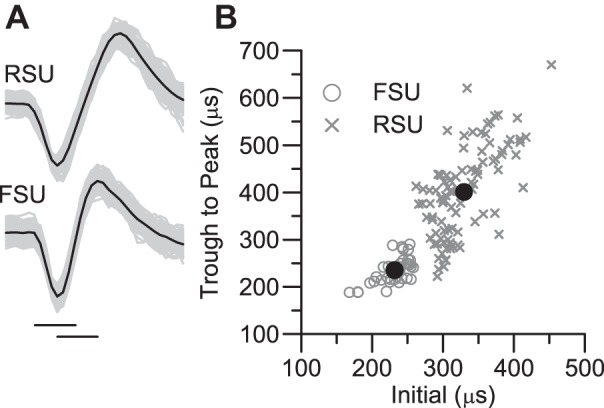

Data were collected at 32 kHz with custom software written for the LabVIEW platform (National Instruments, Austin, TX). Spike waveforms were parsed online based on amplitude and later sorted off-line on the basis of principal components with custom software that permitted visualization of individual spike waveforms in the cluster cutting display. Cluster boundaries were drawn around spikes having similar waveforms. Cut spikes were further examined to eliminate any outlier waveforms, and interspike interval (ISI) histograms were checked to ensure the absence of short intervals indicative of multiple-unit recordings. A subsample of up to 100 waveforms that were preceded by flat baselines were averaged. From these averages we calculated the duration of the initial negative phase and the time between peak negativity and peak positivity (see Fig. 1A). Scatterplots of these measures revealed two nonoverlapping populations (Fig. 1B). Spikes having short initial and trough-to-peak times were classified as fast-spike units (FSUs, presumed inhibitory cells), with longer-duration spikes classified as regular-spike units (RSUs, presumed excitatory barrel neurons). The scatterplots are similar to those of Bruno and Simons, who used slightly different criteria. As noted above, off-line spike sorting was performed without knowledge of the animal's trimming history. Average waveforms were saved as templates for ensuring a match between spikes recorded with the ramp-and-hold deflections and those recorded with the 4-Hz sinusoids used for cross-correlation analyses (see below).

Fig. 1.

Classification of regular-spike (RS) and fast-spike (FS) waveforms. A: average waveforms (dark line) and 100 overlaid traces from a representative regular-spike unit (RSU) and a representative fast-spike unit (FSU). Total length of trace = 1 ms. Horizontal lines below the FS averaged waveform indicate its initial width and trough-to-peak width. B: scatterplot of width measurements for 95 cells classified as RSUs and 37 cells classified as FSUs. The large filled circles denote the units shown in A.

Whisker stimulation.

The PW was deflected with a multiangle whisker stimulator attached to the whisker hair ∼10 mm from the skin surface. First, the PW was deflected in 10 blocks of 8 different directions in 45° increments, randomized within each block. Deflections were 1-mm ramp-and-hold movements having onset and offset velocities of ∼125 mm/s and plateau duration of 200 ms; deflections were centered within a 500-ms period of data collection. Peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) having 1- or 0.1-ms bins were constructed separately for each deflection angle. Spike counts during the 25 ms after stimulus onsets (ON responses) averaged over all eight angles are taken as a measure of responsiveness to whisker deflections; a value of 1.0 spike/stimulus corresponds to a mean firing rate of 40 Hz. Spontaneous activity was calculated during a 100-ms period prior to deflection onset. Interstimulus intervals were ≥1.5 s.

Spike train analyses were performed with LabVIEW and/or Microsoft Excel Visual Basic. Polar plot data were analyzed off-line to assess the strength of ON responses to different angles of whisker movement. We quantified angular tuning as

where is the mean spike count for the maximally effective deflection angle (10 deflections) and is the average spike count over the other seven angles (70 deflections). The tuning index varies from 0.0 for a circular polar plot to 1.0 for a polar plot in which responses are evoked at only a single direction; values are independent of overall firing rate.

We compared the shapes of polar plots of thalamic and cortical cells with a similarity index (SI) calculated, with the Excel CORREL function, as a standard correlation coefficient of the corresponding ON responses of the two simultaneously recorded units to each of the eight angles of whisker deflection (Bruno et al. 2003):

where xi is the ON response of cortical cell X to deflections at angle i, yi is the ON response of thalamic cell Y to deflection at angle i, x̄ and ȳ are the means over all eight angles, sx and sy are the standard deviations, and n = 8. A value of 1.0 indicates identically shaped polar plots; a value of −1.0 denotes opposite shapes.

Simultaneous thalamic and cortical recordings.

Cross-correlation analyses require large numbers of pre- and postsynaptic spikes. To obtain large samples (thousands to tens of thousands of spikes), we stimulated the PW with one hundred 4-s trains of 4-Hz sinusoidal deflections. Deflections were 1 mm peak to peak and began and ended with the whisker's neutral (undeflected) position corresponding to the trough of the sinusoid. Deflections were in a direction that evoked spikes from both thalamic and cortical units based on their polar plots obtained during the recording session. Note that such stimuli were not necessarily in each cell's maximally effective direction because pairs of recorded cells could have dissimilar angular tuning. The low-velocity (4 Hz) stimuli evoked relatively asynchronous thalamic spiking (Temereanca et al. 2008; see results), necessary for cross-correlational approaches. Each 4-s train was preceded by and followed by 500 ms of non-stimulus-driven, e.g., spontaneous, activity.

Functional connectivity for simultaneously recorded TC-RS and TC-FS pairs was assessed by cross-correlating spike trains obtained with the 4-Hz sinusoids. Cross-correlational algorithms were similar to those used by Bruno and Simons. For each pair, a “raw” cross-correlogram (CCG) having 1-ms bins was constructed by measuring the time of occurrence of each cortical spike relative to that of each thalamic spike. To remove stimulus-locked correlation and to assess whether remaining peaks were statistically significant, we used a nonparametric bootstrap procedure. First we resampled data from the 100 trials to produce a “shuffled” CCG histogram based on responses to the whisker stimulus obtained in different trials (Perkel et al. 1967). The shuffled CCG was subtracted on a bin-by-bin basis from the raw CCG to remove stimulus-locked correlations. Resampling was repeated with replacement 5,000 times, each iteration producing a bin-by-bin difference value between the raw and trial-shuffled CCGs. The mean difference for each bin was used as a measure of spike time correlation independent of the whisker stimulus. For each bin we found the 1st percentile confidence limit of the difference distribution constructed from the 5,000 iterations. If the lower limit was >0, the mean difference between raw and trial-shuffled CCGs was deemed statistically larger than expected from chance with P ≤ 0.01. A functional TC connection was inferred if any of the three bins corresponding to time lags +1, +2, or +3 ms reached significance; this corresponds to a probability of detecting a false positive of 0.03. The range of time lags from the TC spike to the cortical spike is consistent with the distribution of TC axonal conduction times plus a short monosynaptic delay (Bruno et al. 2003). Earlier or later significant bins, outside a monosynaptic latency, are not taken as evidence for a direct connection.

The robustness of a connection was assessed by the measure “efficacy,” calculated as

where Nc is the sum of the three lag bins and Npre is the total number of thalamic spikes. For example, a value of 0.02 for a connected pair indicates that a single thalamic spike evokes a cortical spike only 2% of the time. The likelihood of the cortical spike reflects postsynaptic processes as well as the strength of the functional connection, which is not necessarily limited to a single TC synapse per cell. For example, a given spiny barrel neuron is estimated to receive ∼250 TC synapses (Oberlaender et al. 2012a) from ∼90 thalamic barreloid neurons (Bruno and Sakmann 2006; Bruno and Simons 2002). Efficacy is therefore not a measure of individual synaptic contacts and is used only to compare the relative impact of TC spiking on cortical spiking (see discussion).

In several experiments (n = 2 control, 2 trimmed animals) we estimated the strength of firing synchrony between pairs of simultaneously recorded TC cells, without cortical recording. With a multielectrode Eckhorn drive (Uwe Thomas Recording), two or three platinum-in-quartz microelectrodes were positioned within the same physiologically defined thalamic barreloid, and the PW was deflected caudally using the 4-Hz sinusoids (n = 50 trials). Raw CCGs were constructed to evaluate firing synchrony for pairs of cells recorded only on separate electrodes (see Temereanca et al. 2008). Strength was calculated as the normalized number of events occurring within ±10 ms of each other:

where Ncc is the sum of correlated spikes within the time window spanning 0 lag in the CCG and N1 and N2 are the total number of spikes used to construct the CCG. Strength values were calculated separately for prestimulus and stimulus-driven activities.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical tests comparing control and trim units were performed with the Excel Add-In Analyse-It (Analyse-It Software). χ2-Tests were used for comparing categorical data, e.g., relative numbers of connected and nonconnected pairs. Nonparametric Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney tests were used for continuously distributed data; distributions are graphed as box-and-whisker plots showing the median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and range. We report population values as median and range from 1st to 3rd quartiles. For analyses based on linear least-squares regression, we compared slopes for trim vs. control cases (by calculating a t-statistic as the difference between slopes normalized to the pooled estimate of the error variances of the curve fits weighted by their degrees of freedom). For statistical tests indicating rejection of the null hypothesis, we report the obtained P value; when the null hypothesis is accepted, we do not report P values unless they are construed as being at trend level.

RESULTS

Data were obtained from 8 control and 10 trimmed animals. We recorded 121 TCUs (48 control, 73 trim) and 132 cortical cells in topographically aligned layer 4 barrels. From these we obtained 196 paired thalamic and cortical recordings, some cells being used in more than one pairing. Cortical units were classified as RS or FS based on the time course of their spike waveforms (Fig. 1). Ninety-five cells were classified as RSUs (42 control, 53 trim) and 37 as FSUs (18 control, 19 trim). There were no differences between trim and control RS or FS waveforms in terms of their initial or trough-to-peak widths.

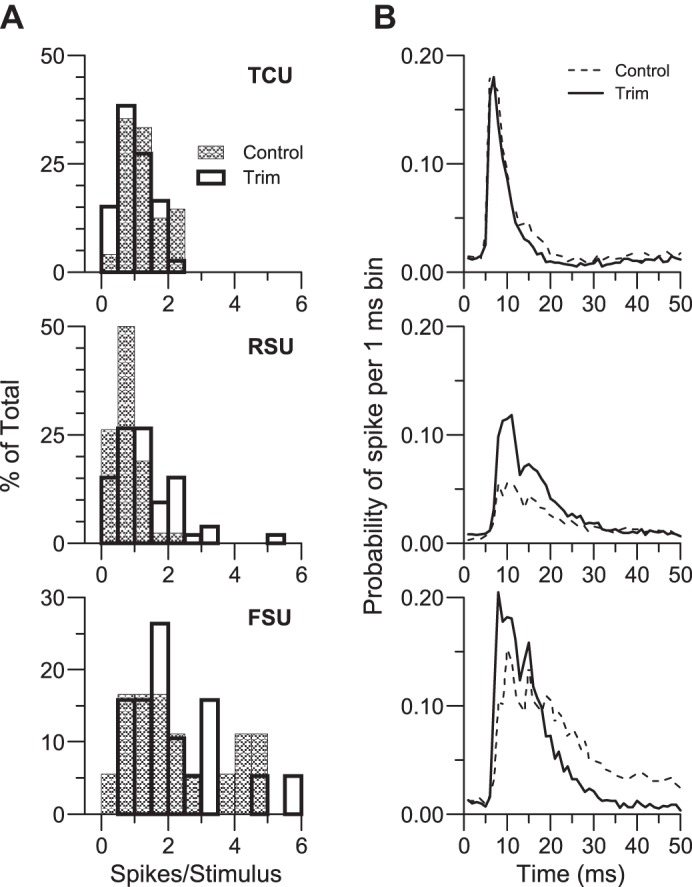

Whisker-evoked ON responses of RSUs were larger in trimmed (spikes/stimulus median = 1.00, 0.531st quartile–1.523rd quartile) vs. control animals (0.61, 0.33–0.82; P < 0.001; see Fig. 2). Spontaneous activities were also higher for trim RSUs (2.87, 1.58–11.8 Hz vs. 2.31, 0.50–6.30 Hz, P = 0.05). Background firing rates of FSUs were equivalent (trim: 6.25, 2.40–17.69 Hz; control: 7.7, 2.98–34.9 Hz). Control vs. trim-evoked responses differed after subtraction of spontaneous rates (P = 0.004). Population RSU PSTHs for stimulus onsets (Fig. 2B, middle) indicated elevated firing during the initial phase of the response and a small second peak of activity ∼10 ms later; cell-by-cell analyses showed that the two response peaks were present to varying degrees in all cells such that the second peak did not reflect activity of a separate, long-latency group. Overall response magnitudes did not differ for FSUs (trim: 1.76, 1.43–3.06 spikes/stimulus; control: 1.73, 1.06–3.93 spikes/stimulus), but, as reported previously (Lee et al. 2007), FSUs in trimmed rats fired more robustly during the first 15 ms of the ON response and less robustly during the latter phase (25–50 ms; Fig. 2B, bottom; all P < 0.03). Trimming-induced decreases in FS cell excitability (Sun 2009) could account in part for the late phase reduction in whisker-evoked FSU firing that would nevertheless be elevated at short latencies because of more effective TC input (see below). TCU responses were smaller in trimmed animals (0.93, 0.63–1.36 vs. 1.16, 0.79–1.57, P = 0.04), but spontaneous activities were equivalent (trim: 11.0, 6.4–19.2 Hz; control: 13.5, 6.8–17.1 Hz). Examination of population PSTHs showed that the difference in evoked responses was due to somewhat shorter-duration firing in the trimmed TCU population, as observed for trimmed FSUs but not RSUs. Results are consistent with previous findings of limited whisker-trimming effects on VPm neurons (Arsenault and Zhang 2006; Simons and Land 1994).

Fig. 2.

Whisker-evoked responses to stimulus onsets averaged over all 8 deflection directions. A: frequency histograms of spikes/stimulus based on a 25-ms window; a value of 1.0 spike/stimulus corresponds to a mean firing rate of 40 Hz. B: population peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) having 1-ms bins accumulated over 80 whisker deflections (8 directions × 10 repetitions). Data from 28 control and 73 trim thalamocortical (TC) units (TCUs), 42 control and 53 trim RSUs, and 18 control and 19 trim FSUs.

We dichotomized cortical units into FS and RS classes based on waveform duration and found that FSUs are on average more responsive than RSUs. As a check on the classification approach, we regressed response magnitude with initial spike width. When all units were examined, cells having shorter-duration waveforms, regardless of classification as FS or RS, had larger ON responses (R2 = 0.12, P < 0.0001); this was also true for control and trim units examined separately. Within populations classified as FS or RS, however, no significant correlations were found between response magnitude and initial spike width for all units combined or examined separately for control and trim cases.

Functional connectivity.

We used cross-correlation analyses to examine functional connectivity in 140 TC-RS pairs and 56 TC-FS pairs. Figure 3, A and B, show shuffle-corrected CCGs for representative control TC-FS and TC-RS pairs. Histogram bars indicate the bin-by-bin mean difference between the raw and shuffle-corrected CCGs based on 5,000 iterations with a bootstrap procedure (see methods). The height of each bar relative to baseline = 0 indicates the magnitude of the relationship at that time lag; the continuous line corresponds to the lower 1% confidence limit of the difference distribution constructed for each 1-ms bin. The TC-RS relationship in Fig. 3A shows a large mean peak difference at a lag of 1 ms consistent with a monosynaptic delay. The lower confidence limit for the difference between raw and trial-shuffled values at this lag exceeds 0, indicating that the mean positive difference would be expected to occur by chance with a probability ≤ 0.01. This is taken as evidence that the TCU evokes spikes in the cortical cell independent of the effects of the whisker stimulus (Perkel et al. 1967). The TC-RS CCG is sharply peaked, having only one significant bin, at the 1.0–1.9 ms lag. For the TC-FS pair in Fig. 3B the peak is broader, and all three bins from 1 to 3.9 ms after the TC cell spiked are statistically significant. Although some of the bins at even longer lags differ significantly from 0, the delay is too long to be considered as evidence for a monosynaptic connection, perhaps reflecting instead a prolonged postsynaptic response in the FS cell.

Fig. 3.

Cross-correlograms (CCGs) of thalamocortical pairs. A: representative stimulus-corrected CCG (vertical bars at 1-ms lags) for a connected TC-RS pair. x-Axis indicates time lag between thalamic and cortical spikes, with a positive lag representing cases where the RSU fired after the TCU; note that bin 0–0.99 corresponds to the 1st millisecond after a thalamic spike. y-Axis indicates mean difference between raw and shuffled values; baseline 0 = no difference. Continuous line indicates the lower confidence limits (CI) for individual bins based on the distribution of 5,000 difference values from the bootstrap procedure (see text). In this example, the line exceeds 0 at the 1st ms lag (indicated by marker) after the reference thalamic spikes at time 0; this indicates that the mean positive difference at this lag would be expected to occur by chance with a probability ≤ 0.01. Data from 15,048 TC and 2,298 RS spikes. B: representative TC-FS pair. Three bins corresponding to the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd ms lags are greater than baseline = 0 and are significantly different from chance based on the bootstrap procedure. Data are based on 15,517 TC and 11,342 FS spikes. C and D: average of peak-normalized difference CCGs for all pairs deemed to be functionally connected. CCGs for TC-FS pairs (D) are similar in control vs. trimmed animals. The peak for trim TC-RS pairs (C) is prolonged relative to control. *Significant difference at lag 3–3.9 ms.

To visualize the temporal difference in trial-corrected CCGs from control and trimmed animals we created average normalized CCGs (Fig. 3, C and D). For each connected pair (see Fig. 4 for numbers of connected pairs), difference values, i.e., the vertical bars in Fig. 3, A and B, were normalized to the bin from −20 to +20 ms lags having the largest mean difference between raw and shuffled values. These normalized CCGs were then averaged to construct population CCGs from connected TC-RS and TC-FS pairs in control and trimmed animals. The difference in time course of the individual example TC-RS and TC-FS pairs in Fig. 3, A and B is evident in the control population CCGs (Fig. 3, C and D). For trim cases the population CCG for TC-RS pairs is broad and similar in time course to the control TC-FS and trim TC-FS pairs, which are also similar to each other. Values at lag 3.0–3.9 ms of the control and trim RS CCGs differ (P = 0.03). Thus RSUs in trimmed animals are more responsive to whisker deflections and are more likely to fire within a longer period of time immediately following a spike in a TC cell from which they receive a monosynaptic functional connection.

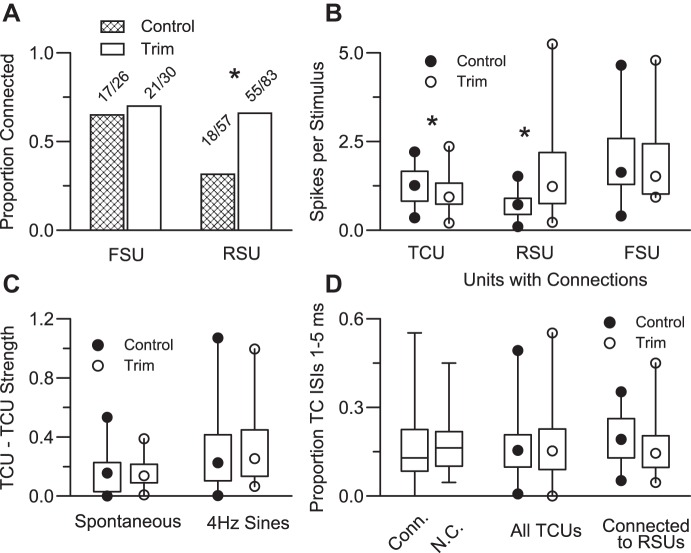

Fig. 4.

Functional connectivity. A: proportions of connected TC-FS and TC-RS pairs in trimmed and control animals. *Significant difference based on χ2 analysis. B: firing rates, as in Fig. 2, represented as box-and-whisker plots (see methods) of units having a functional connection. Connected RSUs in trimmed animals are more responsive, whereas trimmed connected TCUs are less responsive (*). C: strength of TC-TC coincident firing, a measure of synchrony (see methods) based on spontaneous and 4-Hz sinusoid-evoked deflections used for the connectional analyses. Control and trim TCUs have equivalent, low levels of near-synchronous firing. D: TCU firing characteristics: proportions of short (1–5 ms) interspike intervals (ISIs) for all connected (Conn.) and not connected (N.C.) TCUs (left), for all control vs. trim TCUs (center), and for TCUs connected to RSUs in control vs. trimmed animals (right).

Connectivity was higher in trimmed animals, reflecting substantially more functional TC-RS connections (Fig. 4A). TC-FS connections were equivalent in trimmed and control animals (70% vs. 65%). On the other hand, 18 of 57 TC-RS pairs (31.5%) in control animals were connected vs. 55 of 83 trim pairs (66%, χ2, P < 0.0001). Control TC-FS and TC-RS connection rates are nearly identical to those reported previously (Bruno and Simons 2002; see also Bruno and Sakmann 2006). The greater probability of observing TC-RS connections in trimmed animals could simply reflect a large number of false positives due to greater overall activity of trim RSUs. However, spontaneous firing rates were equivalent for connected trim and control cells. Furthermore, we examined connectivity for units having low spontaneous firing or, separately, low 4-Hz evoked firing rates, selecting cells that fired less than or equal to the median of control units; for these subsamples of equivalently low-firing cells, connectivity was still greater for TC-RS pairs in trimmed animals (χ2-tests, all P < 0.004).

Connected RSUs in trimmed animals were more responsive to the eight-angle whisker deflection stimuli than connected RSUs in control animals (Fig. 4B; P < 0.001); no difference was observed for FSUs. In contrast, as in the case of the entire TCU population (Fig. 2), firing rates of connected TC cells were slightly smaller in trim vs. control cases (P = 0.05). We further examined TC-RS connectivity by subdividing TCUs into those firing above or below the trim population median. For the upper halves, 84% (19/25) of TCUs were connected in trimmed animals, whereas 43% (11/29) were connected in control cases (χ2, P = 0.005). Similarly for the lower 50th percentiles, TC-RS connections were twofold more likely to be observed in trimmed animals [62% (36/58)] than in control animals [31% (7/28), χ2, P = 0.001]. Thus, although TC-RS connections were somewhat more common for more responsive TCUs in both trimmed and control animals, TCUs in trimmed animals were more likely to connect to RSUs regardless of their firing rates. Furthermore, TCU firing rates evoked by the 4-Hz stimuli used to determine connectivity were similar between control and trim cases, arguing against a larger number of firing rate-dependent false positives in trimmed pairings. The elevated stimulus-evoked firing of trim RSUs relative to control values likely reflects, in part, their receiving functional inputs from more TC cells rather than from more robustly firing ones (see discussion).

Coincident or near-coincident thalamic spikes preferentially activate barrel neurons. Hence, greater TC-RS connectivity observed in trimmed animals could reflect trimming-induced increases in thalamic firing synchrony. We examined this by calculating the strength of correlated firing in pairs of TCUs recorded simultaneously on different microelectrodes (see methods). For control cases, strength values for spontaneous activity were similar to those from the study by Temereanca et al. (2008), and strength values for the 4-Hz stimuli were within the range expected from that study where 8 Hz, but not 4-Hz, sinusoidal deflections were used. No differences were observed for strength values in trimmed (n = 27 pairs) vs. control (n = 26 pairs) animals for either spontaneous or 4-Hz stimulus-evoked activity (Fig. 4C). We also examined the relative incidence of short TCU ISIs (1–5 ms), inasmuch as more burst firing in trimmed animals could conceivably lead to a greater likelihood of finding functional connections due, possibly, to paired TC spike facilitation (Usrey et al. 2000). For the 4-Hz sinusoidal deflections, there were no differences in the proportion of short TCU ISIs between connected and not-connected pairs, between control and trim TCUs, and between control and trim TCUs connected to RSUs (Fig. 4D). Finally, we performed the cross-correlation analyses with all TC and cortex (RS, FS) short (≤5 ms)-interval spikes deleted. As observed also by Bruno and Simons, these analyses did not affect conclusions regarding connectivity probabilities. For TC-RS, 35% of pairs were connected in control animals vs. 69% in trimmed animals (χ2, P < 0.0001); proportions were unchanged for TC-FS pairs. Thus the greater connectivity found for trim RSUs is unlikely to reflect the firing statistics of their TC inputs.

Angular tuning.

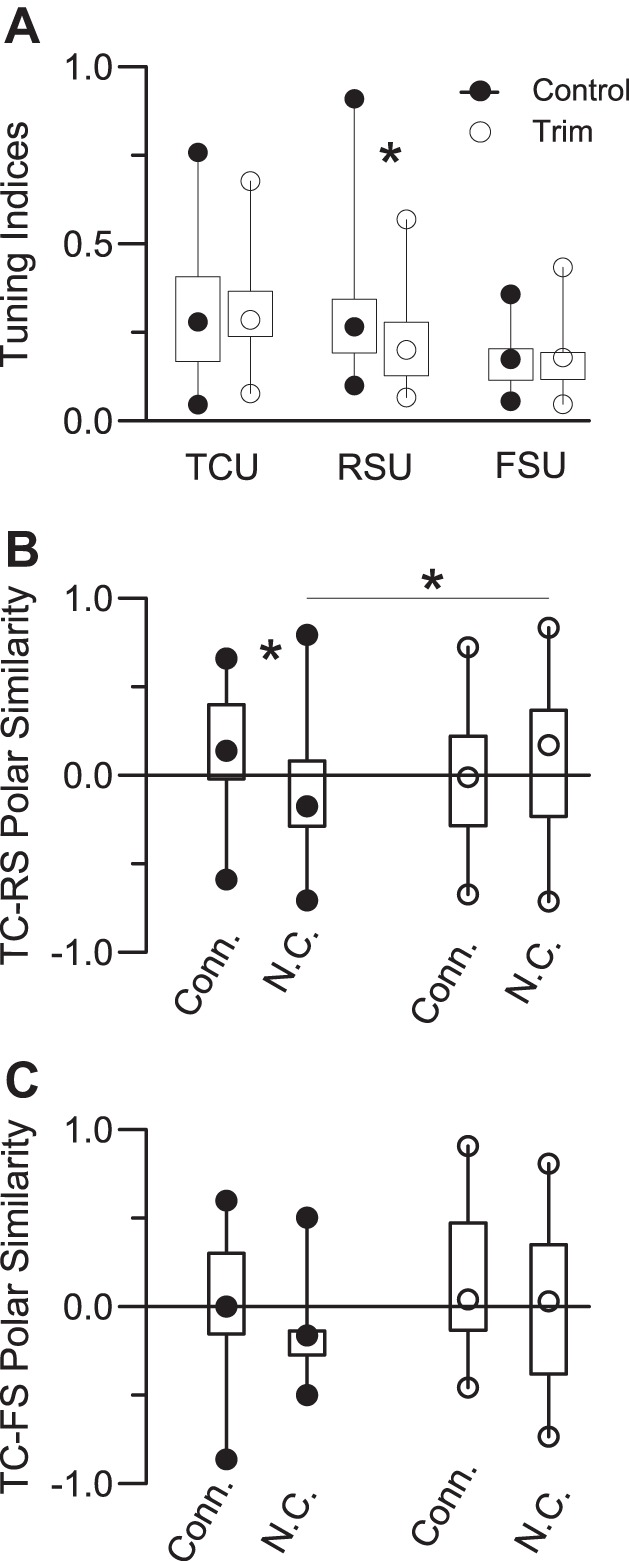

RSUs were less selective for deflection angle in trimmed vs. control animals (Fig. 5A; P = 0.003), whereas there were no trimming-related effects in FSUs and TCUs. In addition, RSUs in control animals are more tuned than FSUs (P = 0.0001), but such is not the case in trimmed animals. We compared simultaneously recorded polar plots from TC-RS and TC-FS pairs with a SI in which cells having identically shaped polar plots have values = 1.0 and oppositely shaped polar plots having values = −1.0 (see methods); values > 0 indicate polar plot similarity. Previously Bruno and Simons showed that in normally reared rats polar plots of connected TC-RS pairs are more similar to one another than polar plots of not-connected pairs. As shown in Fig. 5B, we also find in control animals that SIs are larger for connected vs. not-connected TC-RS pairs (P = 0.006). On average, SI values for connected pairs are >0 (P = 0.05), whereas those for not-connected pairs are <0 (P = 0.027). In contrast, indexes of connected vs. not-connected control TC-FS or trim TC-RS and TC-FS pairs do not differ, nor do any of the distributions differ from 0. SI values for not-connected control RSUs are smaller (more negative) than those of their trim counterparts (P = 0.05); TC-RS values for connected pairs are larger at trend level in control vs. trim cases (P = 0.07). Thus RSUs in control animals are more tuned, being less likely to receive inputs from dissimilarly tuned TCUs. Functional connectivity between trim TCUs and RSUs is less selective.

Fig. 5.

Angular tuning. A: tuning indexes for TCUs (28 control, 73 trim), RSUs (42 control, 53 trim), and FSUs (18 control, 19 trim). Larger values denote more sharply tuned polar plots (see methods). B and C: similarity indexes comparing polar plot shapes of simultaneously recorded TC-RS (B) and TC-FS (C) units. A value of 1.0 indicates identically shaped polar plots; −1.0 indicates oppositely tuned plots. *Significant differences.

Thalamocortical connections and response selectivity.

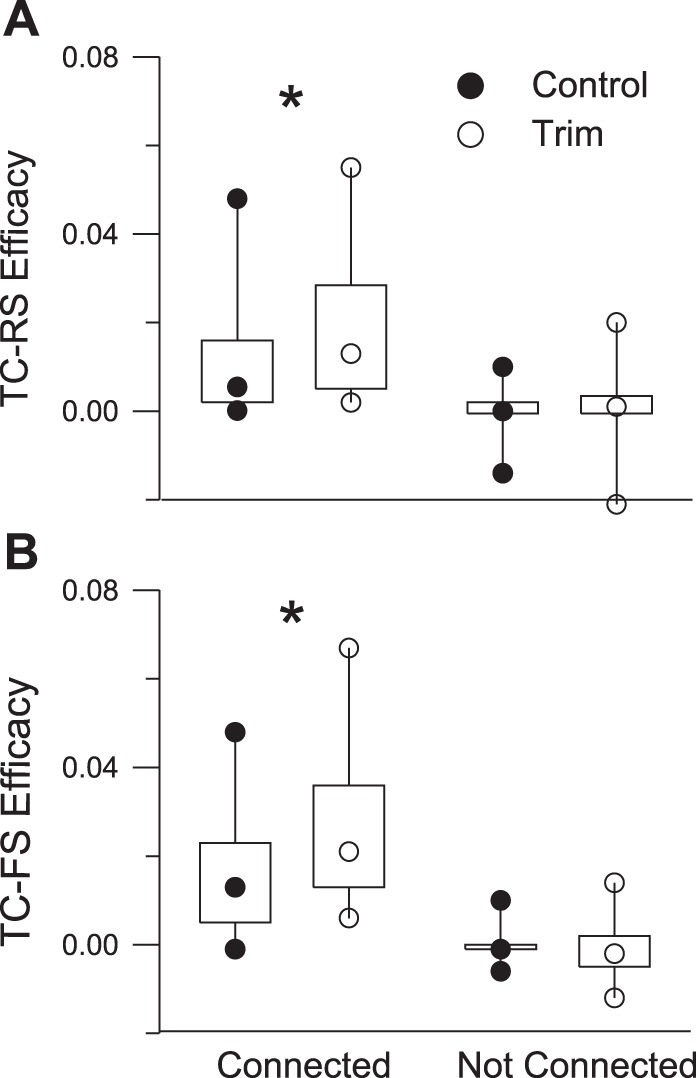

We used efficacy (see methods) as a measure of functional connection strength (Fig. 6). For connected pairs, TC-RS and TC-FS efficacies were larger in trimmed animals relative to their control counterparts (all P < 0.03). In trimmed animals, TC-FS efficacies were larger than TC-RS efficacies (P < 0.04); although TC-FS efficacies were larger than TC-RS efficacies in control animals, the difference did not reach significance (P = 0.16). As expected, in all cases efficacies of connected pairs were larger than those of not-connected pairs (all P < 0.001), with the latter not differing from 0.

Fig. 6.

Efficacy values for connected and not-connected TC-RS (A) and TC-FS (B) pairs. None of the not-connected distributions differs from 0. *Significant differences.

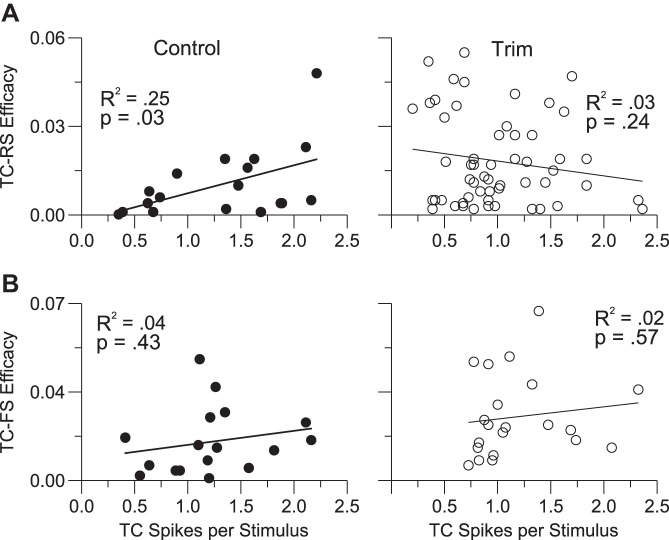

The angular tuning analyses indicate that functional connections between thalamic cells and RS cortical units are less selective in trimmed animals, whereas TC-FS connections are equivalently nonselective. To address this further, we examined the relationship between TC firing and the strength of its cortical contacts. In control TC-RS pairs (Fig. 7A, left) connection efficacy was positively correlated with TC firing; a TC cell that fired more strongly to whisker deflection was more likely to make a strong RSU contact (R2 = 0.25, P = 0.03; note that with the outlying point removed the correlation, though weaker, is still positive, R2 = 0.15, P = 0.12). The converse (negative) relationship was found for trimmed RSUs (R2 = 0.03, P = 0.24) due largely to a number of weakly responding TC cells making some of the strongest functional connections (Fig. 7A, right; note that with the 9 upper left data points omitted the relationship is weak but positive, R2 = 0.066, P = 0.08). Slopes of the control and trim regression lines differ (P = 0.02; when outlier is removed, P = 0.06). In contrast, no significant relationship between TC firing and TC-FS efficacy was observed for either control (R2 = 0.04, P = 0.43) or trim (R2 = 0.02, P = 0.57) cases, and the slopes did not differ (Fig. 7B). Thus compared with control RSUs, trim RS cells, like control and trim FS cells, receive more diverse TCU inputs.

Fig. 7.

Efficacies and firing rates of connected pairs. A: TC-RS efficacies as a function of TC firing rates, measured by ON responses to the 8-direction deflection stimuli. Slopes of regression lines differ between control and trim pairs (see text). B: TC-FS pairs. Slopes of regression lines do not differ.

DISCUSSION

Here we employed single-unit recordings of simultaneously acquired thalamic and cortical spike trains to examine effects of neonatal whisker trimming followed by adult regrowth on functional connections between thalamic VPm neurons and layer 4 barrel neurons that receive direct inputs from them. Our finding of a twofold greater TC-FS vs. TC-RS convergence in control animals is similar to that reported previously with nearly identical extracellular recordings and analyses (Bruno and Simons 2002) and to estimates of TC-RS connectivity based on cross-correlations of TC spiking and RS postsynaptic membrane potentials (Bruno and Sakmann 2006). Whole cell in vitro experiments using TC slices in the whisker barrel system yield similar findings of a twofold greater TC convergence onto FS vs. RS cells (Cruikshank et al. 2007). Physiologically based cross-correlation measures of TC connections to layer 4–6 spiny cells (Constantinople and Bruno 2013) parallel those derived from purely anatomical approaches (Oberlaender et al. 2012a). As regards relative synaptic strengths, Cruikshank et al. found that the larger TC excitatory postsynaptic potentials evoked in FS vs. RS cells reflect in part stronger TC-FS inputs, consistent with our and Bruno and Simons' measures of cross-correlation connection efficacy. Estimates of TC synaptic strengths based on the dendritic locations of morphologically identified TC synapses onto spiny barrel neurons (Schoonover et al. 2014) are nearly identical to those obtained with cross-correlation by Bruno and Sakmann. The consistency of findings with a variety of approaches supports our conclusions regarding trimming-induced alterations in TC connectivity.

Neonatal whisker trimming followed by long periods of whisker regrowth leads to elevated firing of barrel neurons, greater impact of functional TC connections, and twice the probability of finding connected pairs of thalamic and RS cortical neurons. TCU spiking rates and firing synchrony are not increased, with the former actually being somewhat lower than in control animals. Thus elevated firing of barrel neurons in trimmed animals does not simply reflect their receiving inputs from more responsive or more synchronously firing TCUs. Elevated stimulus-evoked firing in trimmed animals occurs as early as the first few milliseconds, corresponding to the arrival time of thalamic spikes. Findings are consistent with barrel neurons in trimmed animals receiving stronger functional TC connections and, in the case of RSUs, more of them.

Previously, Bruno and Simons (2002) and Lee et al. (2007) suggested that abnormally high firing rates in trimmed RSUs reflect a redistribution, relative to control animals, of TC connections such that the more responsive TCUs, reported by Bruno and Simons to contact FSUs preferentially, make and/or maintain connections to RSUs. We did not observe this bias in control animals. We did find, however, that control TCUs are much less likely to contact RSUs than FSUs and that no such bias exists in trimmed animals in which probabilities of observing TC-RS and TC-FS connections are equivalently high. Trim RSUs have a higher incidence of inputs from TCUs with mismatched polar plots as well as mismatched firing-rate associated efficacies. Taken together, these results indicate that functional TC inputs onto RSUs are less selective in trimmed animals. Along with much higher connectivity rates, trim TC-RS relationships appear more similar to those observed for TC-FS pairs in control (and trimmed) animals. During the period of whisker trimming, when firing of thalamic and cortical neurons may be at an abnormally low level, excitatory barrel neurons, like inhibitory cells in normally reared animals, may accept and retain inputs indiscriminately from TCUs. Responses of trim RSUs, like those of control FSUs, would more faithfully display a conjunction of their numerous and diverse TC inputs (Bruno and Simons 2002; Swadlow and Gusev 2002), yielding, for example, reduced angular tuning and broader whisker receptive fields (Shoykhet et al. 2005).

RSUs in 2-wk-old rat pups are more responsive and less tuned than their adult counterparts (Shoykhet and Simons 2008). Perhaps normal whisking behavior, which begins 2 wk postnatally, promotes pruning or weakening of mismatched thalamic inputs onto cells (RSUs) that under normal conditions would retain sparse and weak connections. Abnormal patterns of afferent activity associated with the absence of full-length whiskers could alter developmentally regulated activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, making existing TC synapses stronger and/or preventing their elimination (Feldman et al. 1998). Consistent with this view, compared with control cases trim TC-RS connections have higher efficacy and trim RSUs are as likely to receive inappropriate inputs as appropriate ones.

Barrel neurons are embedded within a densely interconnected network of local excitatory neurons (Petersen and Sakmann 2000). Such connections are thought to reinforce TC-driven activity and enhance the nonlinearity of RSU responses (Pinto et al. 2003). Although excitatory cortico-cortical synapses, like TC synapses, are weak in normally reared rats (Schoonover et al. 2014), trimming-induced increases in their number and/or strength could contribute to elevated RSU activity by enhancing the relative effectiveness of TC inputs. The number of dendritic spines, sites of corticocortical excitatory inputs, is reduced in whisker-trimmed animals, but these changes are transient and are reported to occur in superficial layers, not in layer 4 (Briner et al. 2010). These results contrast with a recent study reporting a whisker trimming-induced increase in some types of dendritic protrusions but a decrease in others on pyramidal cell basilar dendrites in layer 4 of mice (Chen et al. 2015). Mice deprived of their whiskers from birth to 60 days of age, without regrowth, show no changes in the numerical density of asymmetric barrel synapses of nonthalamic origin (Sadaka et al. 2003). Finally, whisker trimming prevents the normally occurring increase in excitatory connectivity among spiny stellate cells that begins at approximately postnatal day 9, and excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) amplitudes are similar in normally reared and whisker-trimmed mice (Ashby and Isaac 2011). Thus available evidence suggests that increased firing in trim barrels is not due to greater local recurrent excitation.

Barrels in neonatally whisker-trimmed animals may be subject to persistent activity-related changes in inhibitory circuitry and its ongoing regulation in adulthood, even after prolonged whisker regrowth. Elevated firing rates of trim barrel neurons are likely due in part to weaker or fewer inhibitory synapses rather than less FSU firing (Jiao et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2007). Our results show that trim FSUs, presumed inhibitory barrel neurons, receive convergent inputs from a high percentage of TC neurons that on average make stronger than normal functional connections. Like RSUs, FSUs in trimmed animals fire more robustly during the earliest phase of the thalamic-evoked response. Thus trimming-induced reductions in intrabarrel inhibition probably reflect changes in the number and/or strengths of inhibitory synapses, as reported by many investigators (see introduction). Our analyses suggest, however, that our finding of a twofold increase in TC-RS connections observed in trimmed animals is unlikely due simply to elevated RS firing associated with reduced intrabarrel inhibition.

Barrel neurons are strongly activated by converging inputs from synchronously firing TCUs (Bruno 2011; Roy and Alloway 2001). In control animals we found that TC-FS connections are much more likely than TC-RS connections. Based on nearly identical findings in normally reared rats (Bruno and Simons 2002), it was estimated that an average RS neuron receives functional connections from ∼90 thalamic barreloid neurons, an average FS neuron receiving ∼160. Analyses of TC synaptic connections with whole cell recordings of excitatory postsynaptic potentials yield similar estimates of TC-RS connectivity (Bruno and Sakmann 2006). Higher responsiveness and more broadly tuned receptive fields of FSUs, relative to RSUs, are thought to reflect at least in part much more extensive TC-FS convergence (Bruno and Simons 2002; Swadlow and Gusev 2002). When accompanied by diminished local inhibition, increased TC-RS connectivity in trimmed rats may similarly contribute to elevated firing rates, reduced angular tuning, and less spatially focused RSU whisker receptive fields.

Does the greater TC-RS functional connectivity observed in trimmed animals reflect more thalamic synapses? Sadaka et al. (2003) found that the number of TC synapses decreased by 43% in the barrels of mice subjected to whisker trimming for the first 60 days of postnatal life. In that study, whiskers were not allowed to regrow. Adult regrowth could possibly result in synapse proliferation or a delay in the elimination of asymmetric synapses, some of which are likely of TC origin, that normally begins at approximately postnatal day 20 (White et al. 1997). A net increase in TC synapses would presumably have to be accompanied by a substantial overshoot to sustained, above-normal numbers in order to account for the twofold greater TC-RS connectivity that we observed. A trimming-induced proliferation of TC-RS synapses would also likely necessitate increased numbers of postsynaptic sites, e.g., spines, on excitatory barrel neurons. As noted above, most of the presently available evidence is inconsistent with this. In this regard, Sadaka et al. found a similar trimming-induced decrease in the number of TC synapses onto smooth barrel neurons, presumed FS interneurons, yet we observed no differences in TC-FS functional connectivity in trimmed vs. control animals. Moreover, in adult-trimmed animals TC axon arborization is reduced, at least in the absence of full whisker regrowth (Oberlaender et al. 2012b). The available evidence is thus inconsistent with the idea that neonatal whisker trimming results in a substantial increase in the number of TC synapses.

A trimming-induced increase in TC-RS functional connectivity may not necessarily require more TC synapses. Cross-correlation analyses based on extracellular recordings provide estimates of functional connectivity, not necessarily measures of the number and/or strength of individual synaptic contacts. Lower spike thresholds due to changes in intrinsic cell properties and/or decreased local inhibition could contribute to the increased probability of inferring a functional connection. We found, however, that the magnitude of spontaneous firing, which we take as a measure of overall cell excitability, was unrelated to connectivity. Connection efficacies were, however, larger in trim TC-RS and TC-FS connected pairs, indicating greater overall functional impact of the contacting TC cell. Increased dendritic nonlinearities, (e.g., Lavzin et al. 2012) could compensate for a net loss of synapses. Perhaps in trimmed animals an individual TC axon, which normally makes multiple synapses on a postsynaptic cell, makes fewer contacts on that neuron but its inputs summate more effectively with those from other TC neurons. Increased clustering of inputs from multiple TC neurons could enhance the synergistic effects of thalamic firing synchrony, making it more likely to observe a functional connection (Ratte et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2010). When accompanied by a trimming-induced reduction in inhibition, RSUs would fire more robustly to whisker deflection and receive efficacious inputs from more TC cells even if an overall reduction in the number of TC synapses persists after whisker regrowth. Interestingly, in normally reared animals Schoonover et al. (2004) found greater clustering of TC synapses on dendrites of star pyramid vs. spiny stellate barrel neurons. In visual cortex the developmental change from pyramidal to stellate morphology requires retinal input (Callaway and Borrell 2011). Accordingly, barrels in whisker-trimmed animals may contain a higher proportion of star pyramids and/or more clustering of TC synapses onto spiny stellate cell dendrites.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-19950 to D. J. Simons.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: D.J.S. and G.E.C. conception and design of research; D.J.S., G.E.C., and H.T.K. performed experiments; D.J.S., G.E.C., and H.T.K. analyzed data; D.J.S., G.E.C., and H.T.K. interpreted results of experiments; D.J.S. and G.E.C. prepared figures; D.J.S. and G.E.C. drafted manuscript; D.J.S., G.E.C., and H.T.K. edited and revised manuscript; D.J.S., G.E.C., and H.T.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Emily Basara for excellent technical assistance and Randy Bruno for many helpful comments.

REFERENCES

- Akhtar ND, Land PW. Activity-dependent regulation of glutamic acid decarboxylase in the rat barrel cortex: effects of neonatal versus adult sensory deprivation. J Comp Neurol 307: 200–213, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Swadlow HA. Thalamocortical specificity and the synthesis of sensory cortical receptive fields. J Neurophysiol 94: 26–32, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault D, Zhang ZW. Developmental remodelling of the lemniscal synapse in the ventral basal thalamus of the mouse. J Physiol 573: 121–132, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby MC, Isaac JT. Maturation of a recurrent excitatory neocortical circuit by experience-dependent unsilencing of newly formed dendritic spines. Neuron 70: 510–521, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briner A, De Roo M, Dayer A, Muller D, Kiss JZ, Vutskits L. Bilateral whisker trimming during early postnatal life impairs dendritic spine development in the mouse somatosensory barrel cortex. J Comp Neurol 518: 1711–1723, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno RM. Synchrony in sensation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21: 701–708, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno RM, Khatri V, Land PW, Simons DJ. Thalamocortical angular tuning domains within individual barrels of rat somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci 23: 9565–9574, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno RM, Sakmann B. Cortex is driven by weak but synchronously active thalamocortical synapses. Science 312: 1622–1627, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno RM, Simons DJ. Feedforward mechanisms of excitatory and inhibitory cortical receptive fields. J Neurosci 22: 10966–10975, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway EM, Borrell V. Developmental sculpting of dendritic morphology of layer 4 neurons in visual cortex: influence of retinal input. J Neurosci 31: 7456–7470, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvell GE, Simons DJ. Abnormal tactile experience early in life disrupts active touch. J Neurosci 15: 2750–2757, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya B, Di Cristo G, Higashiyama H, Knott GW, Kuhlman SJ, Welker E, Huang ZJ. Experience and activity-dependent maturation of perisomatic GABAergic innervation in primary visual cortex during a postnatal critical period. J Neurosci 24: 9598–9611, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Bajnath A, Brumberg JC. The impact of development and sensory deprivation on dendritic protrusions in the mouse barrel cortex. Cereb Cortex 25: 1638–1653, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittajallu R, Isaac JT. Emergence of cortical inhibition by coordinated sensory-driven plasticity at distinct synaptic loci. Nat Neurosci 13: 1240–1248, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinople CM, Bruno RM. Deep cortical layers are activated directly by thalamus. Science 340: 1591–1594, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank SJ, Lewis TJ, Connors BW. Synaptic basis for intense thalamocortical activation of feedforward inhibitory cells in neocortex. Nat Neurosci 10: 462–468, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Ashby MC, Isaac JT. Coordinated developmental recruitment of latent fast spiking interneurons in layer IV barrel cortex. Nat Neurosci 10: 453–461, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham D, Woolsey TA. Acute whisker removal reduces neuronal activity in barrels of mouse SmI cortex. J Comp Neurol 178: 629–644, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC, Isaac JT. Long-term depression at thalamocortical synapses in developing rat somatosensory cortex. Neuron 21: 347–357, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. A critical period for experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci 12: 1826–1838, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand PJ. Plasticity of the rat cortical barrel system. In: Changing Concepts of the Nervous System, edited by Morrison AR, Strick PL. New York: Academic, 1982, p. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN, LeVay S. Plasticity of ocular dominance columns in monkey striate cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 278: 377–409, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inan M, Crair MC. Development of cortical maps: perspectives from the barrel cortex. Neuroscientist 13: 49–61, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Zhang C, Yanagawa Y, Sun QQ. Major effects of sensory experiences on the neocortical inhibitory circuits. J Neurosci 26: 8691–8701, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MJ, Alloway KD. Cross-correlation analysis reveals laminar differences in thalamocortical interactions in the somatosensory system. J Neurophysiol 75: 1444–1457, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MK, Carvell GE, Jobling J, Simons DJ. Sensory loss by selected whisker removal produces immediate disinhibition in the somatosensory cortex of behaving rats. J Neurosci 19: 9117–9125, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land PW, de Blas AL, Reddy N. Immunocytochemical localization of GABAA receptors in rat somatosensory cortex and effects of tactile deprivation. Somatosens Mot Res 12: 127–141, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavzin M, Rapoport S, Polsky A, Garion L, Schiller J. Nonlinear dendritic processing determines angular tuning of barrel cortex neurons in vivo. Nature 490: 397–401, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Land PW, Simons DJ. Layer- and cell-type-specific effects of neonatal whisker-trimming in adult rat barrel cortex. J Neurophysiol 97: 4380–4385, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheva KD, Beaulieu C. An anatomical substrate for experience-dependent plasticity of the rat barrel field cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 11834–11838, 1995a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheva KD, Beaulieu C. Neonatal sensory deprivation induces selective changes in the quantitative distribution of GABA-immunoreactive neurons in the rat barrel field cortex. J Comp Neurol 361: 574–584, 1995b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlaender M, de Kock CP, Bruno RM, Ramirez A, Meyer HS, Dercksen VJ, Helmstaedter M, Sakmann B. Cell type-specific three-dimensional structure of thalamocortical circuits in a column of rat vibrissal cortex. Cereb Cortex 22: 2375–2391, 2012a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlaender M, Ramirez A, Bruno RM. Sensory experience restructures thalamocortical axons during adulthood. Neuron 74: 648–655, 2012b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkel DH, Gerstein GL, Moore GP. Neuronal spike trains and stochastic point processes. II. Simultaneous spike trains. Biophys J 7: 419–440, 1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen CH, Sakmann B. The excitatory neuronal network of rat layer 4 barrel cortex. J Neurosci 20: 7579–7586, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto DJ, Hartings JA, Brumberg JC, Simons DJ. Cortical damping: analysis of thalamocortical response transformations in rodent barrel cortex. Cereb Cortex 13: 33–44, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratte S, Hong S, De Schutter E, Prescott SA. Impact of neuronal properties on network coding: roles of spike initiation dynamics and robust synchrony transfer. Neuron 78: 758–772, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid RC, Alonso JM. Specificity of monosynaptic connections from thalamus to visual cortex. Nature 378: 281–284, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rema V, Armstrong-James M, Ebner FF. Experience-dependent plasticity is impaired in adult rat barrel cortex after whiskers are unused in early postnatal life. J Neurosci 23: 358–366, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SA, Alloway KD. Coincidence detection or temporal integration? What the neurons in somatosensory cortex are doing. J Neurosci 21: 2462–2473, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadaka Y, Weinfeld E, Lev DL, White EL. Changes in mouse barrel synapses consequent to sensory deprivation from birth. J Comp Neurol 457: 75–86, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonover CE, Tapia JC, Schilling VC, Wimmer V, Blazeski R, Zhang W, Mason CA, Bruno RM. Comparative strength and dendritic organization of thalamocortical and corticocortical synapses onto excitatory layer 4 neurons. J Neurosci 34: 6746–6758, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoykhet M, Land PW, Simons DJ. Whisker trimming begun at birth or on postnatal day 12 affects excitatory and inhibitory receptive fields of layer IV barrel neurons. J Neurophysiol 94: 3987–3995, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoykhet M, Simons DJ. Development of thalamocortical response transformations in the rat whisker-barrel system. J Neurophysiol 99: 356–366, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons DJ, Land PW. Early experience of tactile stimulation influences organization of somatic sensory cortex. Nature 326: 694–697, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons DJ, Land PW. Neonatal whisker trimming produces greater effects in nondeprived than deprived thalamic barreloids. J Neurophysiol 72: 1434–1437, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun QQ. Experience-dependent intrinsic plasticity in interneurons of barrel cortex layer IV. J Neurophysiol 102: 2955–2973, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swadlow HA, Gusev AG. Receptive-field construction in cortical inhibitory interneurons. Nat Neurosci 5: 403–404, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temereanca S, Brown EN, Simons DJ. Rapid changes in thalamic firing synchrony during repetitive whisker stimulation. J Neurosci 28: 11153–11164, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usrey WM, Alonso JM, Reid RC. Synaptic interactions between thalamic inputs to simple cells in cat visual cortex. J Neurosci 20: 5461–5467, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Loos H, Woolsey TA. Somatosensory cortex: structural alterations following early injury to sense organs. Science 179: 345–398, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HP, Spencer D, Fellous JM, Sejnowski TJ. Synchrony of thalamocortical inputs maximizes cortical reliability. Science 328: 106–109, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker E, Soriano E, Van der Loos H. Plasticity in the barrel cortex of the adult mouse: effects of peripheral deprivation on GAD-immunoreactivity. Exp Brain Res 74: 441–452, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White EL, Weinfeld L, Lev DL. A survey of morphogenesis during the early postnatal period in PMBSF barrels of mouse SmI cortex with emphasis on barrel D4. Somatosens Mot Res 14: 34–55, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel TN, Hubel DH. Single-cell responses in striate cortex of kittens deprived of vision in one eye. J Neurophysiol 26: 1003–1017, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]