Abstract

An Enterobacter ludwigii strain was isolated during routine screening of a Japanese patient for carriage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. PCR analysis revealed the blaNMC-A carbapenemase gene. Whole-genome sequencing revealed that blaNMC-A was inserted in the chromosome and associated with a novel 29.1-kb putative Xer-dependent integrative mobile element, named EludIMEX-1. Bioinformatic analysis identified similar elements in the genomes of an Enterobacter asburiae strain and of other Enterobacter cloacae complex strains, confirming the mobile nature of this element.

TEXT

Members of the Enterobacter cloacae complex (ECC) are an important cause of health care-associated infections, with a notable propensity to acquire antibiotic resistance determinants (1). The ECC includes at least six species, namely, E. cloacae, Enterobacter asburiae, Enterobacter hormaechei, Enterobacter kobei, Enterobacter ludwigii, and Enterobacter nimipressuralis (1). The epidemiology of these species, however, remains poorly defined since conventional phenotypic methods and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry, which are routinely used in the clinical microbiology laboratory, are unreliable for identification of ECC isolates at the species level (1, 2). Even 16S rRNA gene sequencing is unreliable for identification of ECC isolates at the species level, which requires sequence analysis of additional targets such as the hsp60 and rpoB genes (3, 4).

Carbapenems are among the most reliable drugs for treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant ECC strains. Acquired resistance to carbapenems remains uncommon among isolates of these species and is generally due to overexpression of the resident AmpC β-lactamase in combination with permeability defects or to the production of acquired carbapenemases of different types (VIM, IMP, NDM, OXA-48, KPC, and NMC-A/IMI) (5, 6).

NMC-A is a serine carbapenemase originally detected in a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter strain (NOR-1, initially identified as E. cloacae and subsequently reidentified as E. asburiae) isolated from a soft tissue infection in France in 1990 (7, 8). The enzyme is able to hydrolyze a broad spectrum of β-lactam substrates, with preference for penicillins, narrow-spectrum cephalosporins, and carbapenems (7, 9), and together with IMI-type enzymes belongs to a well-defined lineage of molecular class A β-lactamases (10). In the NOR-1 index strain, the blaNMC-A gene was integrated in the chromosome, and expression was regulated by a LysR-type transcriptional regulator encoded by the nmcR gene, located upstream of the β-lactamase gene (11).

Since the first description, NMC-A has occasionally been reported to occur in E. cloacae isolates from Europe, the United States, and South America (12–15), while closely related enzymes of the IMI-type (IMI-1 to IMI-8, with 98% to 86% amino acid sequence identity to NMC-A) have also been detected in isolates of E. cloacae, E. asburiae, and Escherichia coli from the United States, Europe, the Far East, and South Africa (16–23). Nevertheless, NMC-A and IMI carbapenemases have remained overall uncommon in the clinical setting, unlike other class A serine carbapenemase such as the KPC-type enzymes (24).

Apart from the chromosomal location and the linkage with the nmcR regulatory gene, the genetic context of blaNMC-A has not been further elucidated.

In this work, we investigated an NMC-A-positive isolate of E. ludwigii by whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and identified a novel 29.1-kb genetic element carrying the blaNMC-A gene, which was putatively integrated in the chromosome by a Xer-mediated recombination mechanism.

E. ludwigii AOUC-8/14 was isolated in August 2014 from a surveillance rectal swab taken from a patient upon admission to the Neurointensive Care Unit of Careggi University Hospital of Florence, Italy. The patient was a Japanese tourist admitted to the hospital due to a ruptured brain aneurysm. The isolate grew on the carba section (selective for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae) of the chromID Carba Smart dual medium (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Étoile, France) and was initially identified as E. cloacae or E. asburiae by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Vitek-MS; bioMérieux, France). By reference broth microdilution (25), the isolate was resistant to carbapenems and chloramphenicol but susceptible to piperacillin, piperacillin-tazobactam, expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and colistin (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of E. ludwigii AOUC-8/14

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Ampicillin | >256 |

| Piperacillin | 8 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactama | 1 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanateb | 256 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.125 |

| Cefepime | 0.125 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25 |

| Aztreonam | 4 |

| Amikacin | 2 |

| Gentamicin | 0.25 |

| Tobramycin | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 128 |

| Meropenem | 32 |

| Ertapenem | 8 |

| Doripenem | 8 |

| Colistin | 0.125 |

| Chloramphenicol | 16 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.015 |

Tazobactam at fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

Clavulanate at a 1:2 proportion to amoxicillin.

A crude extract, prepared by sonic disruption of an overnight culture grown in LB medium, revealed the presence of carbapenemase activity (imipenem-hydrolyzing specific activity, 261 ± 3 nmol/min/mg protein) that was not inhibited by EDTA when tested in a spectrophotometric assay as described previously (26). In PCR assays, the isolate tested negative for blaKPC, blaOXA-48, blaNDM, and blaVIM carbapenemase genes (27) and positive for the blaNMC-A gene (13).

The AOUC-8/14 isolate was investigated by draft WGS using an Illumina MiSeq platform and a 2 × 300-bp paired-end approach (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The WGS reads were assembled with A5-miseq (28) and analyzed by BLAST searches using the nr and WGS databases (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Data from WGS identified AOUC-8/14 as E. ludwigii based on sequence analysis of the rpoB and hsp60 genes (4). Identification at the species level was further confirmed by comparison of the WGS data with the genomes of type strains of E. ludwigii and of other species of the ECC using GGDC software, version 2.0 (29) (Table 2). Analysis of the WGS data detected the resident ampC gene, encoding a class C β-lactamase of the ACT lineage identical to that of E. cloacae strain ARC4540 (GenBank accession no. KJ949114), and confirmed the presence of a blaNMC-A gene identical to that of E. asburiae NOR-1 (11).

TABLE 2.

Results of comparative analysis of the genomes of E. ludwigii AOUC-8/14 and other ECC strains carried out using GGDC software, version 2.0 (29)a

| Strain (accession no.) | E. ludwigii EN-119T | E. ludwigii P101 | E. ludwigii EcWSU1 | E. asburiae MNCRE14 | E. asburiae L1 | E. cloacae ATCC 13047T | E. hormachei ATCC 49162T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. ludwigii AOUC-8/14 (LGIV00000000) | 90 | 90 | 91 | 36 | 35 | 34 | 31 |

| E. ludwigii EN-119T (JTLO01000001) | 90 | 90 | 35 | 35 | 34 | 31 | |

| E. ludwigii P101 (CP006580) | 91 | 36 | 36 | 34 | 31 | ||

| E. ludwigii EcWSU1 (CP002886) | 36 | 36 | 34 | 31 | |||

| E. asburiae MNCRE14 (JYMF01000000) | 73 | 36 | 34 | ||||

| E. asburiae L1 (NZ_CP007546) | 36 | 34 | |||||

| E. cloacae ATCC 13047T (NC_014121) | 33 | ||||||

| E. hormachei ATCC 49162T (AFHR01000000) |

The value for each comparison represents the percentage of DNA-DNA relatedness. Values of >70% indicate belonging to the same species. Sequences are from the WGS database (draft genomes) or from the nr database (complete genomes). Complete genomes are boldfaced.

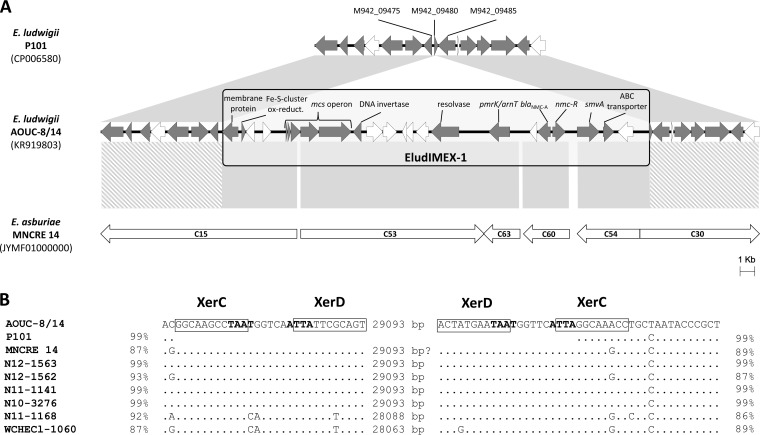

In E. ludwigii AOUC-8/14, the blaNMC-A gene was located in a contig of 888 kb that, in a BLAST comparison, revealed high similarity (>99% nucleotide identity) to the complete genomes of Enterobacter strains P101 (GenBank accession no. CP006580) and EcWSU1 (GenBank accession no. CP002886), reported as E. cloacae in the database entries but reidentified here as E. ludwigii based on analysis of their rpoB and hsp60 genes and on comparisons with the genomes of the E. ludwigii type strain and of strains of other ECC species by the GGDC software (Table 2). A high level of similarity (>99% nucleotide identity) of the contig containing the blaNMC-A gene was also observed with the draft genome of the E. ludwigii EN-119 type strain (accession no. JTLO01000001) (30). Sequence alignment of these regions also revealed that in AOUC-8/14, blaNMC-A was associated with a 29.1-kb DNA insertion that was not present in the other strains and was flanked by two 29-bp imperfect inverted repeats homologous to the XerC/XerD binding sites (31, 32) (Fig. 1). Such sites are present on the chromosome of most bacteria and are targeted by the XerC/XerD tyrosine recombinases to resolve chromosome dimers (31). Xer-mediated recombination events are also involved in the topological maintenance of several plasmids and in integration of mobile DNA elements that are indicated as IMEX (integrative mobile genetic elements exploiting the Xer-mediated recombination mechanism) (31). As such, the DNA insertion associated with the blaNMC-A gene was identified as a putative IMEX and named EludIMEX-1. The element was inserted into the gene defined by locus tag M942_09480 of E. ludwigii P101, encoding a hypothetical protein of unknown function and containing a region of homology to part of the XerC binding site (Fig. 1). The EludIMEX-1 element showed a lower GC content than that of the E. ludwigii AOUC-8/14 genome (39.1% versus 54.6%), further confirming its acquisition by horizontal gene transfer.

FIG 1.

(A) Comparison of the genomic region of E. ludwigii AOUC-8/14 carrying the blaNMC-A gene and the corresponding chromosomal region of E. ludwigii P101 (region 1872587 to 1888317 of GenBank accession no. CP006580), revealing the chromosomal insertion of the EludIMEX-1 element in AOUC-8/14. Comparisons with the corresponding regions of the EcWSU1 and EN-119 E. ludwigii strains yielded identical results and are not shown. ORFs are indicated by arrows, showing direction of transcription. Proteins of unknown function are filled in white. Regions connected by gray areas exhibit >98% nucleotide sequence identity. Comparison with the draft genome of E. asburiae MNCRE14 (GenBank accession no. JYMF01000001) is shown at the bottom. In this case, contigs from WGS of MNCRE14 (indicated by C and contig number) were aligned and ordered according to homology with the corresponding parts of the AOUC-8/14 genome. The regions connected by striped areas exhibit <91% nucleotide sequence identity. (B) Nucleotide sequences at the junctions of EludIMEX-1 with the E. ludwigii AOUC-8/14 chromosome, revealed by alignment with the corresponding E. ludwigii P101 chromosomal region. The imperfect repeats homologous to the XerC/XerD binding sites are boxed, the conserved consensus sequence is boldfaced (32), and the size of the intervening DNA segment (bp) is indicated. A comparison is also shown with the presumptive blaNMC-A-carrying element of strain MNCRE14, with the elements associated with blaNMC-A from ECC strains N12-1563 (GenBank accession no. KR057496.1), N12-1562 (GenBank accession no. KR057495.1), N11-1141 (GenBank accession no. KR057493.1), and N10-3276 (GenBank accession no. KR057492.1), and with the elements associated with blaIMI from ECC strain N11-1168 (GenBank accession no. KR057494.1) and E. cloacae WCHECl-1060 (GenBank accession no. LFDQ01000001). Percentages at the left and right sides of the sequences represent the nucleotide identity with the corresponding region of AOUC-8/14 (for a 10-kb region, except for N12-1563, N12-1562, N11-1141, N10-3276, and N11-1168, which have shorter flanking regions).

EludIMEX-1 carried 23 open reading frames (ORFs), including the blaNMC-A and nmcR genes, a microcin S-like operon similar to that from plasmid pSYM1 from Escherichia coli G3/10 (33), a pmrK (arnT)-like homolog possibly involved in the decoration of bacterial lipopolysaccharide with 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose, putative recombinase, and resolvase genes, and additional ORFs encoding hypothetical proteins of unknown function (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Interestingly, a BLAST search against the WGS database detected the presence of an element very similar to EludIMEX-1 (>98% nucleotide sequence identity) in the draft genome of Enterobacter strain MNCRE14 (GenBank accession no. JYMF01000001), although fragmented in different contigs (Fig. 1). In MNCRE14, reported as E. cloacae in the database but reidentified here as E. asburiae based on analysis of rpoB and hsp60 genes and on genome comparisons by the GGDC analysis (Table 2), this element was inserted at the same genomic position as in AOUC-8/14, in an overall conserved but more divergent genomic context (Fig. 1), in agreement with its belonging to a different species. This observation suggested an independent acquisition of the two elements by recombination at the same chromosomal site and further supported the involvement of a site-specific recombination mechanism in the mobilization of this element.

While this paper was under revision, the sequences of genomic regions associated with blaNMC-A and blaIMI from ECC strains isolated in Canada and China were released in public databases. The regions associated with blaNMC-A (GenBank accession numbers KR057492.1, KR057493.1, KR057495.1, and KR057496.1) were very similar to EludIMEX-1 (>99% nucleotide identity), while those associated with blaIMI (accession numbers KR057494.1 and LFDQ01000001) were more divergent but very similar to each other and clearly related to EludIMEX-1; all were apparently inserted in similar genetic contexts (Fig. 1B).

Altogether, present findings identified a novel putative IMEX that may be responsible for integration of the blaNMC-A carbapenemase gene into the chromosome of Enterobacter spp., apparently via a Xer-dependent recombination mechanism. Related elements may be responsible for chromosomal integration of blaIMI genes. The site specificity requirement and the dependence on the XerC/XerD recombination system may explain the lower promiscuity of this element and the more limited diffusion observed for the blaNMC-A- and blaIMI-type genes compared with that observed for other carbapenemase genes associated with different types of mobile genetic elements.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence of EludIMEX-1 was deposited in the INSDC database under the accession no. KR919803. The whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession no. LGIV00000000. The version described in this paper is version no. LGIV01000000.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from EvoTAR (no. HEALTH-F3-2011-2011-123 282004) to G.M.R.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01452-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mezzatesta ML, Gona F, Stefani S. 2012. Enterobacter cloacae complex: clinical impact and emerging antibiotic resistance. Future Microbiol 7:887–902. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlovic M, Konrad R, Iwobi AN, Sing A, Busch U, Huber I. 2012. A dual approach employing MALDI-TOF MS and real-time PCR for fast species identification within the Enterobacter cloacae complex. FEMS Microbiol Lett 328:46–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann H, Roggenkamp A. 2003. Population genetics of the nomenspecies Enterobacter cloacae. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:5306–5318. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5306-5318.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paauw A, Caspers MP, Schuren FH, Leverstein-van Hall MA, Deletoile A, Montijn RC, Verhoef J, Fluit AC. 2008. Genomic diversity within the Enterobacter cloacae complex. PLoS One 3:e3018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doumith M, Ellington MJ, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2009. Molecular mechanisms disrupting porin expression in ertapenem-resistant Klebsiella and Enterobacter spp. clinical isolates from the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 63:659–667. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. 2011. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1791–1798. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordmann P, Mariotte S, Naas T, Labia R, Nicolas MH. 1993. Biochemical properties of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from Enterobacter cloacae and cloning of the gene into Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 37:939–946. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.5.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girlich D, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2015. Clonal distribution of multidrug-resistant Enterobacter cloacae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 81:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mariotte-Boyer S, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Labia R. 1996. A kinetic study of NMC-A β-lactamase, an Ambler class A carbapenemase also hydrolyzing cephamycins. FEMS Microbiol Lett 143:29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walther-Rasmussen J, Høiby N. 2007. Class A carbapenemases. J Antimicrob Chemother 60:470–482. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naas T, Nordmann P. 1994. Analysis of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase from Enterobacter cloacae and of its LysR-type regulatory protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:7693–7697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pottumarthy S, Moland ES, Juretschko S, Swanzy SR, Thomson KS, Fritsche TR. 2003. NmcA carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme in Enterobacter cloacae in North America. Emerg Infect Dis 9:999–1002. doi: 10.3201/eid0908.030096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radice M, Power P, Gutkind G, Fernández K, Vay C, Famiglietti A, Ricover N, Ayala JA. 2004. First class A carbapenemase isolated from Enterobacteriaceae in Argentina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:1068–1069. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.1068-1069.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Österblad M, Kirveskari J, Hakanen AJ, Tissari P, Vaara M, Jalava J. 2012. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Finland: the first years (2008-11). J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2860–2864. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanco VM, Rojas LJ, De La Cadena E, Maya JJ, Camargo RD, Correa A, Quinn JP, Villegas MV. 2013. First report of a nonmetallocarbapenemase class A carbapenemase in an Enterobacter cloacae isolate from Colombia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3457. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02425-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen BA, Bush K, Keeney D, Yang Y, Hare R, O'Gara C, Medeiros AA. 1996. Characterization of IMI-1 β-lactamase, a class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme from Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40:2080–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu YS, Du XX, Zhou ZH, Chen YG, Li LJ. 2006. First isolation of blaIMI-2 in an Enterobacter cloacae clinical isolate from China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1610–1612. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1610-1611.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu YW, Tung VW, Cheung TK, Chu MY, Cheng N, Lai C, Tsang DN, Lo JY. 2011. Carbapenemases in enterobacteria, Hong Kong, China, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis 17:130–132. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.101443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rojo-Bezares B, Martín C, López M, Torres C, Sáenz Y. 2012. First detection of blaIMI-2 gene in a clinical Escherichia coli strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1146–1147. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05478-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naas T, Cattoen C, Bernusset S, Cuzon G, Nordmann P. 2012. First identification of blaIMI-1 in an Enterobacter cloacae clinical isolate from France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1664–1665. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06328-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teo JWP, La M-V, Krishnan P, Ang B, Jureen R, Lin RTP. 2013. Enterobacter cloacae producing an uncommon class A carbapenemase, IMI-1, from Singapore. J Med Microbiol 62:1086–1088. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.053363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boo TW, O'Connell N, Power L, O'Connor M, King J, McGrath E, Hill R, Hopkins KL, Woodford N. 2013. First report of IMI-1-producing colistin-resistant Enterobacter clinical isolate in Ireland, March 2013. Euro Surveill 18(31):pii=20548 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gqunta K, van Wyk J, Ekermans P, Bamford C, Moodley C, Govender S. 2015. First report of an IMI-2 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter asburiae clinical isolate in South Africa. South Afr J Infect Dis 30:34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, Schwaber MJ, Daikos GL, Cormican M, Cornaglia G, Garau J, Gniadkowski M, Hayden MK, Kumarasamy K, Livermore DM, Maya JJ, Nordmann P, Patel JB, Paterson DL, Pitout J, Villegas MV, Wang H, Woodford N, Quinn JP. 2013. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis 13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard— 10th ed CLSI document M07-A10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauretti L, Riccio ML, Mazzariol A, Cornaglia G, Amicosante G, Fontana R, Rossolini GM. 1999. Cloning and characterization of blaVIM, a new integron-borne metallo-β-lactamase gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:1584–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirel L, Walsh TR, Cuvillier V, Nordmann P. 2011. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 70:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coil D, Jospin G, Darling AE. 2015. A5-miseq: an updated pipeline to assemble microbial genomes from Illumina MiSeq data. Bioinformatics 31:587–589. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auch AF, von Jan M, Klenk HP, Goker M. 2010. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand Genomic Sci 2:117–134. doi: 10.4056/sigs.531120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann H, Stindl S, Stumpf A, Mehlen A, Monget D, Heesemann J, Schleifer KH, Roggenkamp A. 2005. Description of Enterobacter ludwigii sp. nov., a novel Enterobacter species of clinical relevance. Syst Appl Microbiol 28:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das B, Martínez E, Midonet C, Barre FX. 2013. Integrative mobile elements exploiting Xer recombination. Trends Microbiol 21:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krupovic M, Forterre P. 2011. Microviridae goes temperate: microvirus-related proviruses reside in the genomes of Bacteroidetes. PLoS One 6(5):e19893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zschüttig A, Zimmermann K, Blom J, Goesmann A, Pöhlmann C, Gunzer F. 2012. Identification and characterization of microcin S, a new antibacterial peptide produced by probiotic Escherichia coli G3/10. PLoS One 7(3):e33351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.