Abstract

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are important components of the host innate defense mechanism against invading pathogens. Our previous studies have shown that the outer membrane protein, OprI from Pseudomonas aeruginosa or its homologue, plays a vital role in the susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria to cationic α-helical AMPs (Y. M. Lin, S. J. Wu, T. W. Chang, C. F. Wang, C. S. Suen, M. J. Hwang, M. D. Chang, Y. T. Chen, Y. D. Liao, J Biol Chem 285:8985–8994, 2010, http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.078725; T. W. Chang, Y. M. Lin, C. F. Wang, Y. D. Liao, J Biol Chem 287:418–428, 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.290361). Here, we obtained two forms of recombinant OprI: rOprI-F, a hexamer composed of three disulfide-bridged dimers, was active in AMP binding, while rOprI-R, a trimer, was not. All the subunits predominantly consisted of α-helices and exhibited rigid structures with a melting point centered around 76°C. Interestingly, OprI tagged with Escherichia coli signal peptide was expressed in a hexamer, which was anchored on the surface of E. coli, possibly through lipid acids added at the N terminus of OprI and involved in the binding and susceptibility to AMP as native P. aeruginosa OprI. Deletion and mutation studies showed that Cys1 and Asp27 played a key role in hexamer formation and AMP binding, respectively. The increase of OprI hydrophobicity upon AMP binding revealed that it undergoes conformational changes for membrane fusion. Our results showed that OprI on bacterial surfaces is responsible for the recruitment and susceptibility to amphipathic α-helical AMPs and may be used to screen antimicrobials.

INTRODUCTION

Conventional antimicrobials inhibit the synthesis of bacterial nucleic acid, protein, and cell wall components. However, the widespread use of antibiotics in both medicine and agriculture have increased the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria. Unfortunately, the number of new antibiotics in the pipelines of major pharmaceutical companies has been declining in the past decade (1, 2). Thus, development of new antimicrobials with unique targets and mechanisms of action different from those of conventional antibiotics is an acute and urgent need. Natural antimicrobial peptides/proteins (AMPs) that may fill this need have been isolated from multiple sources, including bacteria, fungi, insects, invertebrates, and vertebrates (3–5). These AMPs exert important roles in innate immunity against a broad spectrum of pathogens like bacteria, fungi, enveloped viruses, parasites, and even cancer cells (6, 7).

Although AMPs possess diverse secondary structures, like α-helices, β-strands, and random coils, their surfaces are uniformly amphipathic with cationic and hydrophobic residues on opposite sides (8–10). The former property promotes selectivity for negatively charged components on microbial surfaces, whereas the latter facilitates interactions with fatty acyl chains of the bacterial membrane. Disruption of membrane integrity and subsequent condensation of cytoplasmic components usually occur in the AMP-treated bacteria. Various targets and mechanisms of action of AMPs have been extensively proposed and studied, such as the outer surface lipid, outer membrane protein, inner membrane, inner membrane protein, nucleic acid, and intracellular protein (11–14).

Our previous studies have shown that the outer membrane protein OprI of Pseudomonas aeruginosa or its homologue, Lpp in the Enterobacteriaceae, play a vital role in the susceptibilities of Gram-negative bacteria to cationic α-helical AMPs. These AMPs include SMAP-29 from sheep, CAP-18 from rabbit, and LL-37 from human, but not AMPs with different secondary structures, like polymyxin B from Bacillus polymyxa (15, 16). Although OprI and Lpp exhibit only 30% identity in amino acid sequence, they are mainly composed of long-stranded α-helices of 56 to 64 amino acid residues in length (16, 17). At the N terminus, they start with the Cys-Ser-Ser sequence and anchor onto the outer membrane through the N-terminal modified glycerylcysteine, to which amide- and ester-linked palmitic acids are covalently bound. At the C terminus, most of them are covalently linked to the cell wall by the ε-amino group of terminal lysine residues, while some are not (18–20). However, the mechanism of action of these cationic α-helical AMPs on target proteins such as OprI/Lpp still are unclear. In this report, we obtained two forms of recombinant OprI, as hexamers and trimers, and found that the hexameric recombinant form, rOprI-F, which is composed of three double-stranded α-helices, possesses higher affinity to α-helical cationic AMPs than trimeric rOprI-R. Alternatively, the hexameric OprI expressed on the surface of Escherichia coli was lipidated at the N terminus for anchoring onto the outer membrane and was involved in the binding and susceptibility to AMPs as native OprI of P. aeruginosa. OprI became hydrophobic upon SMAP-29 binding, probably through conformational changes for membrane fusion. The N-terminal cysteine as well as Asp27 play a vital role in the hexamer formation and AMP binding, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptides.

The following oligopeptides and/or their N-terminal biotinylated or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled products, sheep SMAP-29 (RGLRRLGRKIAHGVKKYGPTVLRIIRIAG-NH2), rabbit CAP-18 (GLRKRLRKFRNKIKEKLKKIGQKIQGLLPKLAPRTDY), and human LL-37 (LLGDFFRKSK EKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES), were synthesized by Kelowna International Scientific Inc. (Taipei, Taiwan). Polymyxin B and 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonate (ANS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Missouri, USA).

Size exclusion column multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS).

The molecular weight of rOprI was determined by static light scattering (SLS) using a Wyatt Dawn Heleos II multiangle light scattering detector (Wyatt Technology) coupled to an AKTA purifier UPC10 fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) protein purification system using a Superdex 75 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). A total of 100 μl of 2 mg ml−1 rOprI was applied to the column with a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and 400 mM NaCl by a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min as mentioned previously (21).

Purification of nOprI and sOprI.

Native OprI (nOprI) was extracted from insoluble lysate of P. aeruginosa by 2% SDS at 95°C for 30 min, followed by ultracentrifugation at 38,000 × g, precipitation, and washing by 80% acetone. The pellet was resuspended in 0.25% sodium N-dodecanoylsarcosinate and stored at −20°C. The surface OprI (sOprI) was expressed in E. coli RST2 (Novagen) at 26°C for 6 h without isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction. The proteins in the insoluble lysate were extracted by 0.25% sodium N-dodecanoylsarcosinate at 55°C for 1 h. The soluble fraction after centrifugation at 190,00 × g for 30 min was stored at 4°C.

Antimicrobial activity assay.

Bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa [Schroeter] Migula [ATCC BAA-47TM]) were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth containing 0.17 M NaCl and plated on Luria-Bertani agar. The microbes were grown overnight, washed, and diluted 1:300 in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5. Forty-five microliters of the microbes (5 × 104 to 10 × 104 CFU) was mixed with various concentrations of antimicrobial peptide (5 μl), which was dissolved in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Serial dilutions of each AMP-treated bacterium were prepared and plated for the determination of the remaining colony-forming units. For the assay of the effect of sOprI on the susceptibility of E. coli RST2, bacteria were transformed and incubated for a further 6 h at 26°C after the absorbance of 600 nm reaches 0.6 to ∼0.8. Both parental and transformed bacteria were kept at 4°C before use. At least three independent experiments were performed for each assay to present average values with standard deviations.

Cross-linking assay.

Small aliquots of various OprIs and AMPs were incubated with various concentrations of 1-ethyl-3(3-dimethylaminopropyl carbodiimide) (EDC), a cross-linker, in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 5.5, or glutaraldehyde in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, at 37°C for 30 min. The cross-linked complexes were separated by reduced SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining or Western blotting using anti-OprI or anti-SMAP-29 antibody.

Measurement of ANS fluorescence.

The emission spectra of 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonate (ANS) excited at 380 nm were measured between 400 and 600 nm at 20°C using a temperature-controlled fluorimeter (FP8500; Jasco, Japan) (22). A small volume of ANS stock solution was added to a 200-μl solution (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl) containing 80 μg/ml rOprI-F, 80 μg/ml rOprI-R, and/or 10 μg/ml SMAP-29. The ANS concentration was adjusted to 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 μM as indicated throughout the study.

Measurement of fluorescence polarization.

For fluorescence polarization experiments, SMAP-29 was labeled with FITC at the N terminus. The OprIs (200 μM) were added to the well containing 10 nM FITC-labeled SMAP-29 in 20 mM HEPES and 50 mM NaCl at pH 7.4. Reactions were measured by use of a SpectraMax paradigm plate reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) with an excitation wavelength of 494 nm and emission wavelength of 518 nm. Data were analyzed and plotted by use of GraphPad Prism 5 (San Diego, CA).

Pulldown of OprI by biotinylated AMPs.

Streptavidin-conjugated beads were incubated with biotinylated SMAP-29 or LL-37 in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.15% Triton X-100 for 2 h at 4°C on a rolling wheel. The complexes were mixed with recombinant OprI, incubated for 4 h at 4°C, washed three times with 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.15% Triton X-100, and visualized by Coomassie blue staining or Western blotting.

The methods for cloning, expression, and purification of OprI, circular dichroism (CD) experiments, and measurement of molecular mass by mass spectrometry are described in the supplemental material.

RESULTS

Two forms of recombinant OprI.

Recombinant OprI was excised from maltose-binding protein (MBP) by protease factor Xa (Fig. 1A, lane 3) and then heated at 55°C for 30 min to remove MBP as well as most impurities (Fig. 1A, lanes 4 and 5). The OprIs remaining in the supernatant were separated into two peaks by FPLC Superose 12 gel filtration chromatography and named rOprI-F and rOprI-R for the front and rear peaks, respectively (Fig. 1B). rOprI-F was mostly composed of dimeric subunits, while rOprI-R was both dimer and monomer as analyzed by nonreducing SDS-PAGE and as shown in Fig. 1A, lanes 8 and 9. However, most of the dimers that are either rOprI-F or rOprI-R were dissociated into monomers in reducing environments (Fig. 1A, lanes 6 and 7). Interestingly, a small portion of the proteins remained in dimer formation even after being heated to 95°C for 10 min in 700 mM 2-mercaptothanol (2-ME) and 2% SDS. The original molecular mass of most rOprI-F was 13,894 Da but became 6,948 Da after 2-mercaptoethanol treatment (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material). Thus, OprI is suspected to be a disulfide bridge-linked dimer. In contrast, the masses of the rOprI-R subunits were 13,894 Da and 6,980 Da, respectively (see Fig. S1C). The addition of 32 Da in one of the rOprI-R subunits may be derived from posttranslational modification of the N-terminal cysteine residue. These results suggest that rOprI-F is composed mainly of disulfide bridge-linked dimers, while rOprI-R is composed of dimers and modified monomers.

FIG 1.

Preparation and configuration of two recombinant OprIs, rOprI-F and rOprI-R. (A) Analysis of recombinant OprI at different purification steps. Proteins were separated by 14% SDS-PAGE and stained by Coomassie blue. Lane 1, crude lysate from E. coli BL21(DE3) transformed with a maltose-binding protein (MBP)/OprI-fused gene; lane 2, eluate of nickel-affinity gel; lane 3, protease factor Xa-digested product; lanes 4 and 5, supernatant and pellet of protease-digested products after heat treatment and centrifugation; lanes 6 and 7, front peak (rOprI-F) and rear peak (rOprI-R) of Superose 12 column eluates; lanes 8 and 9, rOprI-F and rOprI-R analyzed by nonreducing SDS-PAGE. (B) Gel filtration chromatography of rOprI. Immunoglobulin (IgG; 150 kDa), bovine serum albumin (BSA; 66 kDa), and bovine RNase A (RNase A; 14 kDa) were used as molecular size markers. (C) SEC-MALS analysis of rOprI. Horizontal line segments above the elution peaks correspond to calculated molar mass (left ordinate axis), and the corresponding molecular mass is indicated in Daltons. The solid line corresponds to relative UV absorbance at 280 nm, and the dashed line in gray represents light scattering (right ordinate axis). (D and E) Configuration of rOprI-F and rOprI-R after cross-linking with EDC. rOprI-F and rOprI-R were incubated with increasing amounts of EDC, as indicated, at pH 5.5 for 30 min and subjected to 14% SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (4 μg protein in each lane) (D) and Western blot analysis (0.8 μg protein in each lane) (E). Numbers 1 to 6 represent the status of rOprI polymerization.

Configuration of recombinant OprI.

To examine the compositions of both rOprIs under native conditions, we performed another SEC-MALS using Superdex 75. The SEC-MALS analysis yielded two distinct symmetric peaks at an elution volume of ca. 9 and 10.8 ml with molecular masses of 42.8 ± 0.3 kDa and 20.9 ± 0.2 kDa, respectively (Fig. 1C). This reveals that rOprI-F and rOpr-R exist as hexamers and trimers, respectively. To further study the configurations of rOprI-F and rOprI-R, both proteins were analyzed by reduced SDS-PAGE after cross-linking with EDC. Monomer, dimer, trimer, tetramer, pentamer, and hexamer were observed in the cross-linked rOprI-F as detected by Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 1D) and Western blotting (Fig. 1E). On the other hand, only monomer, dimer, and trimer were observed in rOprI-R. With respect to the secondary structure of recombinant OprI, both proteins were predominantly composed of rigid α-helices, as shown by the CD spectra displaying two negative ellipticities at 209 and 220 nm and exhibiting high thermal stabilities with melting points (Tm) of 75.6°C and 76.7°C for rOprI-F and rOprI-R, respectively (Fig. 2A and B). These results indicate that rOprI-F is a hexamer composed of six α-helical subunits, while rOprI-R is a trimer composed of three α-helical subunits.

FIG 2.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectrum analyses of OprI. (A) Circular dichroism spectrum analysis of 20 μM rOprI-F and rOprI-R in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl. M.E., molar ellipticity. (B) Equilibrium circular dichroism titration experiments of 20 μM rOprI-F and rOprI-R as a function of temperature monitored at 220 nm.

AMP-binding ability of recombinant OprI.

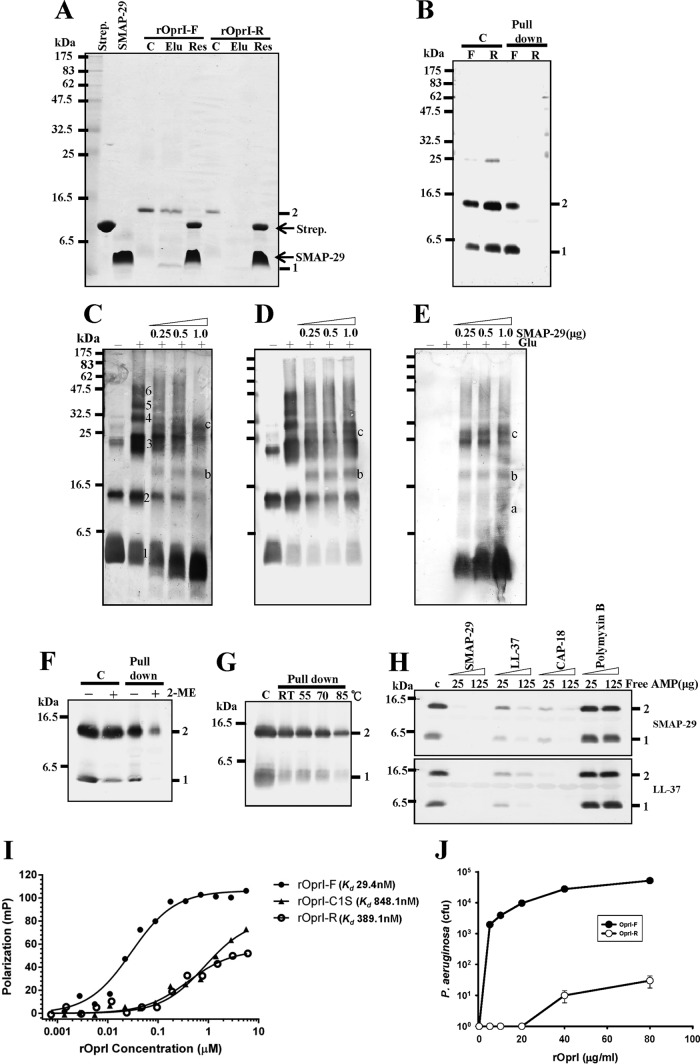

rOprI-F was observed to bind to biotinylated SMAP-29 and was further pulled down by streptavidin gel, eluted by 0.75% sodium N-dodecanoylsarcosinate, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 3A) or eluted directly by 2% SDS and visualized by Western blotting (Fig. 3B), while rOprI-R was not detected under the same assay conditions. SMAP-29 formed a complex with rOprI-F when visualized by silver staining (Fig. 3C) or Western blotting using anti-OprI and anti-SMAP-29 antibody after glutaraldehyde cross-linking and SDS-PAGE separation (Fig. 3D and E). The AMP-binding ability of rOprI-F was labile to reducing agent (15 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) but resistant to heat inactivation of up to 70°C just below its Tm value, 75.6°C (Fig. 3F to G). rOprI-F was able to bind not only SMAP-29 but also other cationic α-helical AMPs, like LL-37. The binding of OprI-F to biotinylated SMAP-29 was competed for by the addition of exogenous free-form SMAP-29, CAP-18, and LL-37 in descending order but not by the cyclic polypeptide polymyxin B (Fig. 3H, top). Similarly, the binding of rOprI-F to biotinylated LL-37 was competed for by SMAP-29 and CAP-18 and partially by LL-37 itself (Fig. 3H, bottom). The binding abilities of FITC-labeled SMAP-29 to rOprI-F and rOprI-R were measured by fluorescence polarization with dissociation constants (Kd) of 29.4 nM and 389.1 nM, respectively (Fig. 3I). The addition of exogenous rOprI-F was able to protect Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the action of SMAP-29, while rOprI-R was less effective, with a thousandfold reduction in colony formation at 20 to ∼80 μg/ml rOprI (Fig. 3J). These results demonstrated that AMPs with cationic α-helical structure are recognized by hexameric rOprI-F, which is resistant to heat (70°C) but susceptible to reducing agent (15 mM).

FIG 3.

Differential AMP-binding ability of rOprI-F and rOprI-R. (A) Pulldown experiments by biotinylated SMAP-29-streptavidin gel. The biotinylated SMAP-29 was incubated with streptavidin-conjugated gels (Strep.) in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and then with rOprI-F and rOprI-R (4 μg each), and finally it was eluted by 0.75% sodium N-dodecanoylsarcosinate, separated by nonreducing SDS-PAGE, and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. C, Elu, and Res represent control without pulldown, N-dodecanoylsarcosinate eluate, and residual proteins, respectively. (B) Pulldown experiments similar to those shown in panel A. The biotinylated SMAP-29 was incubated with streptavidin-conjugated beads in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.15% Triton X-100, with rOprI-F and rOprI-R (2 μg each), and then separated by reduced SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blotting using anti-OprI antibody. C, F, and R represent control, rOprI-F, and rOprI-R, respectively. (C to E) Formation of rOprI-F and SMAP-29 complex. rOprI-F (0.4 μg each) was incubated with increasing amounts of SMAP-29 for 30 min, cross-linked with 0.02% glutaraldehyde for 20 min, separated by 14% reduced SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by silver staining (C), Western blotting with anti-OprI antibody (D), or anti-SMAP-29 antibody (E). Numbers 1 to 6 represent the status of rOprI-F polymerization, and letters a to c indicate the positions of rOprI-F/SMAP-29 complexes. (F) Sensitivity of rOprI-F to reducing agent. rOprI-F was incubated in 15 mM 2-mercaptoethanol for 10 min at room temperature (RT) before SMAP-29-binding experiments as described for panel B. (G) Thermal stability of rOprI-F to bind SMAP-29. rOprI-F was treated at 55°C, 70°C, or 85°C for 10 min before binding to SMAP-29. (H) Competition of the formation of OprI-F-SMAP-29 complex by free cationic α-helical AMPs. rOprI-F (2 μg each) was incubated with biotinylated SMAP-29 in the presence of free SMAP-29, CAP-18, LL-37, and polymyxin B. (I) Fluorescence polarization of the interaction between FITC-SMAP-29 and various OprI variants. (J) Repression of antimicrobial activity of SMAP-29 by exogenous recombinant OprI. P. aeruginosa (5 × 104 to 10 × 104 CFU) was treated with 0.1 μM SMAP-29 in the presence of exogenous rOprI-F and rOprI-R as indicated. At least three independent experiments were performed for each bactericidal assay to present average values with standard deviations. Some statistical bars could not be drawn clearly due to the very minor experimental variations at high CFU values.

Expression of lipidated OprI on the surface of E. coli in hexamer.

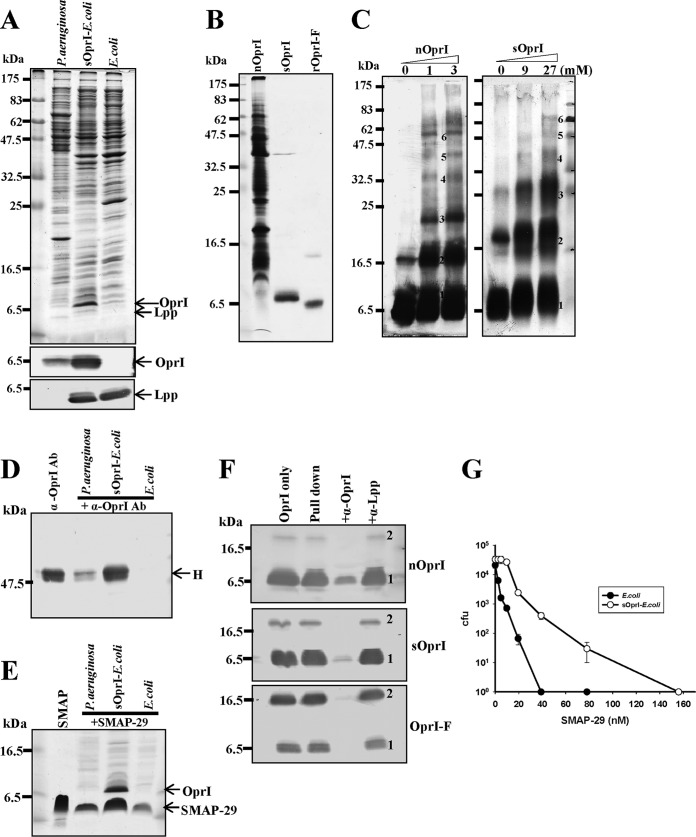

The OprI of P. aeruginosa tagged with the signal peptide of Escherichia coli Lpp at the N terminus, named sOprI, was overexpressed in E. coli. The amount of sOprI in transformed E. coli was much more abundant than that in P. aeruginosa, while the endogenous Lpp in the transformed E. coli was similar to that of parental cells, as shown in Fig. 4A. Both the native OprI (nOprI) extracted from P. aeruginosa and the overexpressed OprI (sOprI) from transformed E. coli RST2 were partially purified, as shown in Fig. 4B. Using mass spectrum analysis, we found that most sOprI precursors (mass of 8,886 Da) were processed and lipidated by three fatty acids (mainly palmitic acid) at the N terminus through glycerylcysteine (mass of 7,735 Da), while some unprocessed sOprI was converted into dimers through a disulfide bridge (mass of 17,771 Da). The palmitic acid of the triacylated lipoprotein may be replaced by other fatty acids, like myristic acid (mass of 7,707 Da) or stearic acid (mass of 7,763 Da) (see Fig. S1D and E in the supplemental material) (19, 20, 23). Both sOprI and nOprI existed in hexameric forms, like rOprI-F, when analyzed by Western blotting after EDC cross-linking (Fig. 4C). sOprI was located on the surface of transformed E. coli, similar to nOprI on P. aeruginosa, because both bacteria were recognized and bound by anti-OprI antibody, while parental E. coli was not (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that the lipidated sOprI resides on the surface of bacteria in hexamer and is exposed to outside environments.

FIG 4.

Hexameric OprI expressed on the surface of E. coli having AMP-binding ability. (A) Expression of OprI. The total lysates of P. aeruginosa, sOprI-transformed E. coli RST-2, and parental cells (107 CFU) were separated by 14% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Coomassie blue staining (top), Western blotting with anti-OprI antibody (middle), or anti-Lpp antibody (bottom), respectively. (B) SDS-PAGE analyses of OprI extracted from P. aeruginosa (nOprI; 21 μg), sOprI-transformed E. coli (sOprI; 2 μg), and recombinant OprI excised from MBP-fused protein (rOprI-F; 1.6 μg) visualized by Coomassie blue staining. (C) Analyses of oligomerization of nOprI (left) and sOprI (right). nOprI (0.7 μg each) and sOprI (0.02 μg each) were incubated with increasing amounts of EDC at pH 5.5, as indicated, containing 0.25% sodium N-dodecanoylsarcosinate for 30 min and subjected to 14% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. (D and E) The binding abilities of P. aeruginosa, sOprI-transformed E. coli RST2, and parental cells to anti-OprI antibody (Ab) or SMAP-29. Bacteria (107 CFU) were incubated with anti-OprI antibody (4 μg) or SAMP-29 (3 μg) in 100 μl at 37°C for 30 min, washed by 0.4 M NaCl, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. H represents the heavy chain of immunoglobulin. (F) SMAP-29 binding ability of various OprIs. The biotinylated SMAP-29 bound to streptavidin-conjugated gels was incubated with nOprI (14 μg), sOprI (2 μg), and rOprI-F (2 μg), respectively, in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.15% Triton X-100 in the absence or presence of anti-OprI and anti-Lpp antibodies (4 μg each) for blocking the AMP-binding activity of OprI. After pulling down and washing, the OprIs were visualized by Western blotting using anti-OprI antibody. (G) Susceptibilities of sOprI-transformed and parental E. coli RST2 cells to SMAP-29. The cold-stored bacteria (5 × 104 to 10 × 104 CFU) were treated with SMAP-29 and assayed for their viabilities. Average values with standard deviations are presented.

AMP binding and susceptibility of sOprI and native OprI to AMPs.

The transformed E. coli having abundant sOprI on its surface possessed stronger SMAP-29 binding ability than parental cells and even more than P. aeruginosa, as visualized by Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 4E). To see whether the increase of AMP-binding ability is mediated through OprI, the specific interaction between SMAP-29 and OprIs from various sources was examined in vitro. All three OprIs (nOprI, sOprI, and rOprI-F) could be bound by SMAP-29 and repressed by anti-OprI antibody but not by anti-Lpp antibody, which is unable to react with OprI (Fig. 4F). Perhaps surprisingly, we found that the sOprI-transformed E. coli was less susceptible to SMAP-29 than parental E. coli (Fig. 4G). These results reveal that the hexameric OprI, lipidated or nonlipidated, is involved in binding and even susceptibility to AMP.

Key residues for the hexamer formation and AMP-binding ability.

To examine key residues responsible for dimer/hexamer formation and AMP binding, several deletions and mutations were made, including N-terminal C1S substitution, sub-N-terminal deletions (d2-3-OprI, d2-10-OprI, d2-13-OprI, and d2-17-OprI), and C-terminal deletions (dC4-OprI, dC8-OprI, dC11-OprI, and dC15-OprI). These mutated OprIs were expressed and purified to homogeneity similar to that of the wild type (wt). Both front (hexamer) and rear (trimer) peaks also were obtained by Superose 12 gel filtration chromatography for all deletion mutants except C1S-OprI, which lacked the front peak (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). The front peak of all mutants was mostly composed of disulfide bridge-linked dimers, as revealed by reduced and nonreducing SDS-PAGE (see Fig. S2B) and mass spectrum analyses. Interestingly, the rear peak of C1S-OprI was exclusively composed of monomer and has a molecular mass of 6,932 Da without dimer formation and with a 32-Da addition (see Fig. S1F). The CD spectra of most mutants were similar to that of wild-type OprI, displaying two negative ellipticities at 209 and 220 nm but exhibiting different thermal stabilities (Fig. 5A to D). The Tms of C1S-OprI, d2-3-OprI, and d2-10-OprI were 69.9°C, 69.9°C, and 64.5°C, respectively, and those of dC4-OprI, dC8-OprI, and dC11-OprI were 69.6°C, 57.2°C, and 46.4°C, respectively, much lower than that of wild-type rOprI-F, 75.6°C. These results indicate that the residues close to N and C termini also play important roles in maintaining the rigid structure of OprI, especially at the region near the C terminus. The front peak of most OprI mutants was hexameric, as visualized by Western blotting after EDC cross-linking, while C1S-OprI and dC15-OprI were trimeric (Fig. 5E and F). For AMP-binding ability, most mutants except C1S-OprI and dC15-OprI were able to recognize biotinylated SMAP-29 (Fig. 6A). The binding affinity of C1S-OprI to SMAP-29 was even weaker than that of rOprI-R, with a Kd of 848.1 nM (Fig. 3I). Moreover, most OprI mutants also were able to protect bacteria from SMAP-29 action except C1S-OprI and dC15-OprI (Fig. 6B and C). To examine key residues for AMP binding, two suspected acidic residues at the b site of the heptad repeats of OprI (described in Discussion) were converted to basic residues D27R and D34K. We found that the ability to bind SMAP-29 and protect the bacteria from the action of 0.1 μM SMAP-29 were markedly decreased (10- to 100-fold reduction in colony formation) if Asp27 was mutated to Arg but not by D34K substitution at a concentration of 1 to 6 μg/ml OprI, which equals 0.14 to 0.85 μM monomeric OprI (Fig. 6A and D). It is interesting that both mutants still possessed hexameric structure similar to that of wild-type OprI (Fig. 5G; also see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). These results suggest that residues 18 to 53 are critical for the formation of α-helix, Cys1 for the formation of dimer as well as hexamer, and Asp27 for AMP binding.

FIG 5.

Analyses of secondary structure and configurations of OprI variants. (A and C) Circular dichroism spectrum analyses of 20 μM OprI variants in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl. (B and D) Equilibrium circular dichroism titration experiments as a function of temperature monitored at 220 nm. (E to G) EDC cross-linking of OprI variants. The OprI variants (0.8 μg each) were incubated with 125 mM EDC at pH 5.5 for 30 min and subjected to 14% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Numbers 1 to 8 represent the status of rOprI polymerization.

FIG 6.

AMP-binding abilities of OprI variants. (A, bottom) The OprI variants (2 μg each) were pulled downed by biotinylated SMAP-29 as described in the legend to Fig. 3B. (Top) A volume of 0.4 μg of each rOprI variant was used as a control without the pulldown experiment. (B, C, and D) Protection of bacteria from AMP action by OprI variants. The viability of P. aeruginosa (5 × 104 to 10 × 104 CFU) was determined after being treated with 0.1 μM SMAP-29 in the presence of OprI variants. Average values with standard deviations are presented.

Changes of hydrophobicity of rOprI upon AMP binding.

To investigate the possible mechanism of amphipathic AMP on OprI, which is anchored on the bacterial outer membrane, the changes of OprI hydrophobicity were traced by the fluorescence hydrophobic dye 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonate (ANS). The emission spectra of ANS in the presence of rOprI-F, rOprI-R, and/or SMAP-29 were determined in vitro, with an emission maximum at 520 nm in free form and a blue shift to 470 nm once bound to hydrophobic residues of protein/peptide. Our results showed that the emission spectra of ANS in the presence of 10 μg/ml SMAP-29 or 16 μg/ml rOprI-R alone was not significantly changed from that of free dye in increasing ANS concentration (5 to 40 μM) (Fig. 7A and B and E). However, the fluorescence intensity slightly increased, and the blue shift (470 nm; left arrow) moved to a red shift (520 nm; right arrow) in increasing concentrations of ANS if rOprI-R was preincubated with SMAP-29 (Fig. 7F). Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity in the presence of rOprI-F was higher than that of rOpr-R (Fig. 7C and E). Most interestingly, the fluorescence intensity markedly increased, and both red and blue shift phenomena also were observed if rOprI-F was treated with SMAP-29 (Fig. 7C and D). These results reveal that rOprI-F is more susceptible to amphipathic AMP than rOprI-R and becomes hydrophobic once bound by SMAP-29.

FIG 7.

Changes of emission spectra of OprI-associated ANS driven by SMAP-29. The emission spectra of ANS in the presence of 10 μg/ml SMAP-29 and/or 80 μg/ml rOprI were measured in 200 μl solution. ANS was added and adjusted to the indicated concentrations (lines 1 to 6 at 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 μM, respectively). Arrows indicate the wavelength of emission maximum at 470 nm or 520 nm, emitted by bound- and free-form ANS, respectively. (A) ANS alone; (B) SMAP-29; (C) rOprI-F; (D) rOprI-F plus SMAP-29; (E) rOprI-R; (F) rOprI-R plus SMAP-29.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria has created an urgent need for the development of novel classes of antimicrobials with mechanisms of action different from those of conventional antibiotics. The discovery of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) from multiple sources may fill this need (3, 4, 6, 24). For example, the protegrin-derived β-stranded oligopeptide, iseganan, is currently in a phase III trial for the prevention of oral mucositis in patients receiving chemotherapy (25, 26). Disruption of membrane integrity, membrane leakage, or condensation of cytoplasmic components usually occurs in AMP-treated bacteria. Various mechanisms of action of AMPs on bacterial targets have been extensively proposed and studied (11–14). Our previous studies showed that the outer membrane blebs and detaches from the inner membrane in hRNase7-treated P. aeruginosa and SMAP-29-treated Klebsiella pneumonia. OprI/Lpp on the surface of the bacteria was recognized and internalized into cytosol by AMP in vivo. Direct binding of these α-helical cationic AMPs to OprI/Lpp also was observed in vitro (15, 16). In this report, we focus on the configuration, location, and active residues of OprI responsible for AMP binding and the conformational changes upon AMP binding to permeate the bacterial membrane.

E. coli mutants deficient in Lpp form large blebs on their surface, leak periplasmic enzymes into the medium, and have difficulty forming septa during cell division (27). Lpp is known to be one of the major outer membrane proteins of E. coli (7.2 × 105 molecules/cell), and it exists in two major forms. A bound form is linked to the peptidoglycan of the cell wall through the C-terminal lysine residue, while the free form remains flexible. However, both forms contain N-acyl-S-diacylglycerylcysteine at the N terminus for integrating into the outer membrane (18, 19, 28–30). The bound form has been suggested to link to the outer membrane and cell wall, while the function of the free form remains unclear. The composition and location of Lpp have been studied in several aspects. First, Lpp is suggested to be composed of six α-helices in a tubular channel through the outer membrane with a hydrophilic interior and hydrophobic outer surface (31). In contrast, a Cys1-deficient Lpp is determined to be a trimeric α-helix with numerous polar and charged residues on its surface and is suspected to reside in the periplasm linking the outer membrane and cell wall (32–34). However, a free form of Lpp having cysteine at the N terminus spans the outer membrane, and its C terminus is exposed to the outer surface instead of linking to the cell wall like the bound form (28).

OprI is one of the major outer membrane lipoproteins of P. aeruginosa, with 30% identity in amino acid sequence to E. coli Lpp, and exists in two forms, free and bound forms, as has been found in E. coli (20). In this study, we obtained two forms of recombinant OprI, rOprI-F and rOprI-R, which are different from mutants deficient in Cys-1 or Lys58/64 as reported by other groups, with both having N-terminal cysteines at which lipid acids are added for outer membrane integration and the C-terminal Lys64 functions in cell wall anchoring (32, 34). rOprI-F forms hexamers and has a greater ability to bind AMP than rOprI-R, which forms trimers. In addition, the former is more hydrophobic than the latter, and it became even more hydrophobic upon AMP binding. The lipidated OprI (sOprI) on the surface of transformed E. coli in hexamer was able to bind AMP in vivo, similar to the case in P. aeruginosa. Furthermore, the OprIs (nOprI, sOprI, and rOprI-F) were able to bind SMAP-29 regardless of their lipidated or nonlipidated status, and their activities were repressed by anti-OprI antibody but not by anti-Lpp antibody (Fig. 4F). Therefore, we propose that the free-form hexameric OprI is anchored onto the outer membrane through three fatty acids at the N terminus and exposed to the outside environments for AMP recognition. With respect to posttranslational modification of lipidated OprI, two ester-linked as well as one amide-linked fatty acids (mainly palmitic acid) are suspected to be added at the N-terminal glycerylcysteine based on mass spectrum analysis as shown in Fig. S1D and E in the supplemental material. The lipid components (mainly palmitic acid) of triacylated lipoproteins may be replaced with other fatty acids, such as myristic acid or stearic acid, for lipoproteins with masses of 7,707 Da and 7,763 Da, respectively (19, 20, 23).

The structure of monomeric OprI was predicted to consist of a long helix and a heptad repeat characteristic of coiled coils by the COILS program, using the structure of E. coli Lpp-56 as a template (32, 35, 36). Therefore, the elution volume of rOprI-F on gel filtration chromatography was less than that of globular bovine serum albumin (BSA), although the latter possessed a higher molecular mass than hexameric rOprI-F, as shown in Fig. 1B. The differential elution behaviors of gel filtration chromatography also were observed in extended proteins having the same molecular sizes (37). To investigate the composition of rOprI, we used SEC-MALS analysis along with EDC cross-linking and found that the molecular masses of rOprI-F and rOprI-R are 42.8 ± 0.3 kDa and 20.9 ± 0.2 kDa, respectively (Fig. 1C). This result indicates that rOprI-F and rOprI-R are hexamers and trimers, respectively.

In this study, the configuration of rOprI-R was found to be a three-stranded α-helix similar to that of E. coli Lpp56. The amino acid sequence of OprI contain 10 alanines in the hydrophobic a and d positions of the five heptad repeats from residues Ala19 to Ala50 (Fig. 8A). The trimeric assembly could be stabilized by interhelical hydrophobic interactions through alanines in the a and d positions of the heptad repeat, while two of them were further tethered by a disulfide bridge at the N terminus and the third remained flexible. The addition of 32 Da to the third subunit may be derived from oxidization of N-terminal cysteine to cysteine sulfinic acid, which was not observed in C1S-rOprI (Fig. 8B; also see Fig. S1C and F in the supplemental material) (38). rOprI-F, which possessed a greater ability to bind AMP and became more hydrophobic than rOprI-R upon AMP binding, is a hexamer composed of three pairs of two-stranded α-helices (Fig. 8C). Each pair of the dimeric α-helices is suspected to be tethered by disulfide bridges at the N terminus and stabilized by salt bridges and hydrogen bonds between oppositely charged residues in the pairings of c to f and b to g (Fig. 8D). Three pairs of dimeric α-helices are further assembled into hexamers through hydrophobic interaction between alanines in the a position of one of the dimeric α-helixes to alanines in the d position of an adjacent helix, similar to that of trimeric rOprI-R (39). Therefore, the alanine clusters of the second α-helix having hydrophobic faces are exposed to outside environments instead of buried in the central core, which is seen with trimeric rOprI-R. Furthermore, the acidic residues, like Asp27, in the b position of the heptad repeats in combination with the nearby alanine clusters render the hexameric rOprI-F accessible to amphipathic AMP through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, respectively (Fig. 8C and D).

FIG 8.

Proposed model of the structure of trimeric and hexameric OprIs. (A) Helical wheel projections of residues 10 to 64 of monomeric OprI. The 4,3 hydrophobic heptad repeats are labeled in a through g positions. (B) Three-stranded α-helices showing hydrophobic interactions between alanine residues in positions a and d. (C) Diagram of hexameric OprI and AMP complex. Three pairs of two-stranded α-helices, which are held together by salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, and a disulfide bond, are assembled into hexamer by hydrophobic interactions through the core subunits of the dimers, similar to the trimeric OprI, as shown in panel B. The amphipathic AMPs are located between alanine clusters and acidic residues in the b position. (D) The binding forces within the paired two-stranded α-helices are attributed to the disulfide bond between N-terminal cysteines, salt bridges, and hydrogen bonds between charged residues. Bars in boldface and stars represent disulfide bonds and modifications at the N terminus of α-helical OprI, respectively. Gray areas, solid lines, and dotted lines represent hydrophobic interaction, salt bridge, and hydrogen bond, respectively. Gray circles and squares represent the main body and hydrophobic residues of amphipathic α-helical AMP, respectively.

Our results showed that OprI deficient or modified at Cys1 is only able to form trimers, not hexamers, while OprIs deleted near the N terminus (residues 2 to 10) or C terminus (residues 54 to 64) still retained the α-helical and hexameric structures, although they had lower Tms. These results suggest that the 10 alanine residues from Ala19 to Ala50 in the a and d positions of heptad repeats are critical for the formation of polymeric and α-helical structures either in dimers or trimers by hydrophobic interactions. The subterminal regions are able to strengthen the α-helical structure of OprI, although they are not essential. Based on the mutation and functional studies, Asp27 rather than Asp34 at the b site of the heptad repeat plays a key role in AMP binding. It is worth mentioning that Asp27 is the sole acidic residue which is conserved in the amino acid sequence of OprI of P. aeruginosa and Lpp of the Enterobacteriaceae family of bacteria (16). Therefore, we propose that the amphipathic AMPs are recognized and bound by the hexameric rOprI-F through a specific negatively charged residue at the b position of heptad repeats, like Asp27, and then move or bind simultaneously to the hydrophobic Leu/Ala residues at the a and d positions (Fig. 8C). Further biophysical studies utilizing X-ray crystallography of the rOprI-F/AMP complex may be helpful in elucidating the exact binding sites of AMPs or conformational changes upon AMP binding.

The increase in AMP binding and reduction of susceptibility of sOprI-transformed E. coli to SMAP-29, as shown in Fig. 4E and G, are suspected to occur for the following reasons. First, OprI-associated proteins may be required to assist the conformational change or internalization of OprI after AMP treatment, which exists in P. aeruginosa but not in E. coli. Second, the ratio of AMP to OprI/Lpp has to reach a threshold for AMP to trigger the change in OprI conformation and even membrane integrity, although the amount of sOprI markedly increased on the surface of transformed E. coli. In addition, it is worth mentioning that during the preparation of recombinant OprI, most impurities as well as fused maltose-binding protein (MBP) after protease Xa cleavage were inactivated at 55°C and removed, at which point rOprI still retained the secondary structure and AMP binding ability, as shown in Fig. 2B and 3G.

In conclusion, our previous studies have shown that OprI is accessible to exogenous anti-OprI antibody, cross-linking agent (EDC), and antimicrobial peptide/protein (SMAP-29 and hRNase 7) and is internalized into the cytosol after AMP treatment (15, 16). Here, we further demonstrated that rOprI-F is a hexamer composed of three α-helical dimers linked by an N-terminal disulfide bridge. The surface OprI is anchored on the bacterial outer membrane through lipid acids hanging on the N-terminal Cys residue. Cys1 as well as the coiled coils (residues 18 to 53) are essential for hexamer formation and Asp27 for AMP binding. The increase of hydrophobicity of OprI upon AMP binding suggests that OprI is able to recruit amphipathic AMP through specific negatively charged residues as well as hydrophobic residues and becomes hydrophobic to permeate the bacterial outer membrane (Fig. 8C).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Proteomics Core Facility of the Institutes of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica, for assistance in mass spectrometry analysis and the Biophysical Instrumentation Laboratory at the Institute of Biological Chemistry, Academia Sinica, for performing fluorescence polarization experiments. We also thank Chinpan Chen for assistance in CD spectrum analysis and Li-Wen Chen and Chia-En Huang for their assistance in the preparation of recombinant OprIs.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Council (NSC 101-2320-B-001-019-MY3) and funds from Academia Sinica and Ministry of Science and Technology Taiwan (104-0210-01-09-02).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01406-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams KJ, Bax RP. 2009. Challenges in developing new antibacterial drugs. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 10:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock RE. 2000. Cationic antimicrobial peptides: towards clinical applications. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 9:1723–1729. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.8.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zasloff M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown KL, Hancock RE. 2006. Cationic host defense (antimicrobial) peptides. Curr Opin Immunol 18:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epand RM, Vogel HJ. 1999. Diversity of antimicrobial peptides and their mechanisms of action. Biochim Biophys Acta 1462:11–28. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(99)00198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock RE, Sahl HG. 2006. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat Biotechnol 24:1551–1557. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tjabringa GS, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. 2005. The human cathelicidin LL-37: a multifunctional peptide involved in infection and inflammation in the lung. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 18:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brogden KA, Kalfa VC, Ackermann MR, Palmquist DE, McCray PB Jr, Tack BF. 2001. The ovine cathelicidin SMAP29 kills ovine respiratory pathogens in vitro and in an ovine model of pulmonary infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:331–334. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.331-334.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis SM, Anderson NN, Forsyth WR, Espiritu C, Conway BD, Greenberg EP, McCray PB Jr, Lehrer RI, Welsh MJ, Tack BF. 2000. Bactericidal activity of mammalian cathelicidin-derived peptides. Infect Immun 68:2748–2755. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.5.2748-2755.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroder JM, Harder J. 2006. Antimicrobial skin peptides and proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci 63:469–486. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5364-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen LT, Haney EF, Vogel HJ. 2011. The expanding scope of antimicrobial peptide structures and their modes of action. Trends Biotechnol 29:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolas P. 2009. Multifunctional host defense peptides: intracellular-targeting antimicrobial peptides. FEBS J 276:6483–6496. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brogden KA. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol 3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang YC, Lin YM, Chang TW, Wu SJ, Lee YS, Chang MD, Chen C, Wu SH, Liao YD. 2007. The flexible and clustered lysine residues of human ribonuclease 7 are critical for membrane permeability and antimicrobial activity. J Biol Chem 282:4626–4633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin YM, Wu SJ, Chang TW, Wang CF, Suen CS, Hwang MJ, Chang MD, Chen YT, Liao YD. 2010. Outer membrane protein I of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a target of cationic antimicrobial peptide/protein. J Biol Chem 285:8985–8994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang TW, Lin YM, Wang CF, Liao YD. 2012. Outer membrane lipoprotein Lpp is gram-negative bacterial cell surface receptor for cationic antimicrobial peptides. J Biol Chem 287:418–428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.290361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duchene M, Barron C, Schweizer A, von Specht BU, Domdey H. 1989. Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane lipoprotein I gene: molecular cloning, sequence, and expression in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 171:4130–4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inouye M, Shaw J, Shen C. 1972. The assembly of a structural lipoprotein in the envelope of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 247:8154–8159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoyye S, Takeishi K, Lee N, DeMartini M, Hirashima A, Inouye M. 1976. Lipoprotein from the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: purification, paracrystallization, and some properties of its free form. J Bacteriol 127:555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizuno T, Kageyama M. 1979. Isolation of characterization of a major outer membrane protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Evidence for the occurrence of a lipoprotein. J Biochem 85:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu W, Feng X, Zheng Y, Huang CH, Nakano C, Hoshino T, Bogue S, Ko TP, Chen CC, Cui Y, Li J, Wang I, Hsu ST, Oldfield E, Guo RT. 2014. Structure, function and inhibition of ent-kaurene synthase from Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Sci Rep 4:6214. doi: 10.1038/srep06214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andley UP, Chakrabarti B. 1981. Interaction of 8-amino-1-naphthalenesulfonate with rod outer segment membrane. Biochemistry 20:1687–1693. doi: 10.1021/bi00509a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basto AP, Piedade J, Ramalho R, Alves S, Soares H, Cornelis P, Martins C, Leitao A. 2012. A new cloning system based on the OprI lipoprotein for the production of recombinant bacterial cell wall-derived immunogenic formulations. J Biotechnol 157:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser R, Harder J, Lange H, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroder JM. 2005. Antimicrobial psoriasin (S100A7) protects human skin from Escherichia coli infection. Nat Immunol 6:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ni1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giles FJ, Redman R, Yazji S, Bellm L. 2002. Iseganan HCl: a novel antimicrobial agent. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 11:1161–1170. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.8.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elad S, Epstein JB, Raber-Durlacher J, Donnelly P, Strahilevitz J. 2012. The antimicrobial effect of Iseganan HCl oral solution in patients receiving stomatotoxic chemotherapy: analysis from a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, phase III clinical trial. J Oral Pathol Med 41:229–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fung J, MacAlister TJ, Rothfield LI. 1978. Role of murein lipoprotein in morphogenesis of the bacterial division septum: phenotypic similarity of lkyD and lpo mutants. J Bacteriol 133:1467–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowles CE, Li Y, Semmelhack MF, Cristea IM, Silhavy TJ. 2011. The free and bound forms of Lpp occupy distinct subcellular locations in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 79:1168–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sankaran K, Wu HC. 1994. Lipid modification of bacterial prolipoprotein. Transfer of diacylglyceryl moiety from phosphatidylglycerol. J Biol Chem 269:19701–19706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tokunaga M, Tokunaga H, Wu HC. 1982. Post-translational modification and processing of Escherichia coli prolipoprotein in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79:2255–2259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.7.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inouye M. 1974. A three-dimensional molecular assembly model of a lipoprotein from the Escherichia coli outer membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 71:2396–2400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.6.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shu W, Liu J, Ji H, Lu M. 2000. Core structure of the outer membrane lipoprotein from Escherichia coli at 1.9 A resolution. J Mol Biol 299:1101–1112. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Cao W, Lu M. 2002. Core side-chain packing and backbone conformation in Lpp-56 coiled-coil mutants. J Mol Biol 318:877–888. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi DS, Yamada H, Mizuno T, Mizushima S. 1986. Trimeric structure and localization of the major lipoprotein in the cell surface of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 261:8953–8957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geourjon C, Deleage G. 1995. SOPMA: significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus prediction from multiple alignments. Comput Appl Biosci 11:681–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. 1991. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uzgiris EE, Cline H, Moasser B, Grimmond B, Amaratunga M, Smith JF, Goddard G. 2004. Conformation and structure of polymeric contrast agents for medical imaging. Biomacromolecules 5:54–61. doi: 10.1021/bm034197+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shetty V, Neubert TA. 2009. Characterization of novel oxidation products of cysteine in an active site motif peptide of PTP1B. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 20:1540–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen C, Parry DA. 1990. Alpha-helical coiled coils and bundles: how to design an alpha-helical protein. Proteins 7:1–15. doi: 10.1002/prot.340070102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.