Abstract

While much is known concerning azole resistance in Candida albicans, considerably less is understood about Candida parapsilosis, an emerging species of Candida with clinical relevance. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of azole resistance in a collection of resistant C. parapsilosis clinical isolates in order to determine which genes might play a role in this process within this species. We examined the relative expression of the putative drug transporter genes CDR1 and MDR1 and that of ERG11. In isolates overexpressing these genes, we sequenced the genes encoding their presumed transcriptional regulators, TAC1, MRR1, and UPC2, respectively. We also sequenced the sterol biosynthesis genes ERG3 and ERG11 in these isolates to find mutations that might contribute to this phenotype in this Candida species. Our findings demonstrate that the putative drug transporters Cdr1 and Mdr1 contribute directly to azole resistance and suggest that their overexpression is due to activating mutations in the genes encoding their transcriptional regulators. We also observed that the Y132F substitution in ERG11 is the only substitution occurring exclusively among azole-resistant isolates, and we correlated this with specific changes in sterol biosynthesis. Finally, sterol analysis of these isolates suggests that other changes in sterol biosynthesis may contribute to azole resistance in C. parapsilosis.

INTRODUCTION

Although Candida albicans classically has been, and currently remains, the most commonly isolated organism of the species, approximately 50% of all Candida infections are attributable to one of the non-albicans species of Candida. Reports of rising rates of these species are increasingly common in the literature, and of these, Candida parapsilosis is of particular concern (1, 2). Population-based surveillance has determined that the incidence of C. parapsilosis candidemia increased 2-fold between 2008 and 2011 and is responsible for 10 to 20% of all candidemia cases in North America (3, 4). It can lead to a wide spectrum of manifestations, including endocarditis, meningitis, ocular infections, vulvovaginitis, and urinary tract infections. This organism has a propensity for forming biofilms on catheters and other implanted medical devices and within high glucose-containing solutions, such as total parenteral nutrition. Nosocomial acquisition is fostered by the unique ability of this organism to grow on inanimate objects and surfaces, and by the documented spread by health care workers via hand carriage. Also, as it is the predominant fungal pathogen recovered in neonatal intensive care units and is associated with neonatal mortality, C. parapsilosis is of specific concern for the pediatric population (5, 6).

The azole antifungals, and particularly fluconazole, are often first-line therapies for candidemia, and therefore, there has been much investigation of azole resistance in C. albicans, the most frequently isolated human fungal pathogen (7). Indeed, several mechanisms of azole resistance have been described. The overexpression of ERG11, which encodes the azole target enzyme sterol demethylase, leads to its increased production, which overwhelms the activity of the drug. This often occurs due to activating mutations in the gene encoding the transcriptional regulator Upc2 (8, 9). Also, mutations in ERG11 that lead to amino acid substitutions alter target protein structures, reduce drug binding affinity, and increase azole resistance (10). A less commonly observed mechanism is the inactivation of sterol desaturase due to a mutation in ERG3. This permits the fungal cell to bypass the production of toxic methylated sterols in the presence of the azole antifungal and results in resistance to azoles and amphotericin B (11). In addition to these mechanisms, two types of transporters have been shown to contribute to azole resistance in C. albicans. Overexpression of the ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters Cdr1 and Cdr2 results in the efflux of all azole antifungals, whereas overexpression of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter Mdr1 results in the efflux of fluconazole and voriconazole (12, 13). Overexpression of CDR1 and CDR2 is due to activating mutations in the transcription factor gene TAC1, whereas overexpression of MDR1 is due to activating mutations in the transcription factor gene MRR1 (14, 15).

Previous studies have provided limited information concerning azole resistance in C. parapsilosis. One study has correlated the overexpression of MDR1 and mutations within MRR1 with fluconazole resistance in laboratory-derived resistant isolates of C. parapsilosis (2). More recently, a surveillance study of a collection of clinical C. parapsilosis isolates again implicated MDR1 and MRR1 in fluconazole resistance in this species; however, a direct role for these genes in azole resistance was not established. This study also identified a mutation in ERG11 leading to the Y132F substitution in sterol demethylase in many of the resistant isolates (16). This substitution has been shown to contribute directly to fluconazole resistance in C. albicans (17).

In the present study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of azole resistance in a collection of resistant C. parapsilosis complex clinical isolates to determine which genes might play a role in this process within this species. We examined the relative expression of the putative drug transporter genes CDR1 and MDR1 and that of ERG11. In isolates overexpressing these genes, we sequenced the genes encoding their presumed transcriptional regulators, TAC1, MRR1, and UPC2, respectively. We also sequenced the sterol biosynthesis genes ERG3 and ERG11 in these isolates to find mutations that might contribute to this phenotype in this Candida species. Our findings demonstrate that the putative drug transporters Cdr1 and Mdr1 contribute directly to azole resistance and suggest that their overexpression is due to activating mutations in the genes encoding their transcriptional regulators. We also observed the Y132F substitution to be the only substitution occurring exclusively among azole-resistant isolates and correlated this with specific changes in sterol biosynthesis. Finally, sterol analysis of these isolates suggests that other changes in sterol biosynthesis may contribute to azole resistance in C. parapsilosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

All C. parapsilosis isolates used in this study are listed in Table 1. The isolates were kept as frozen stock in 40% glycerol at −80°C and subcultured on YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 1% dextrose) agar plates at 30°C. YPD liquid medium was used for routine growth of strains, while YPM (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 1% maltose) liquid medium was used for induction of the MAL2 promoter in the constructed strains. Nourseothricin (200 μg/ml) was added to YPD agar plates when needed for the selection of isolates containing the SAT1 flipper cassette (18). One Shot Escherichia coli strain TOP10 chemically competent cells (Invitrogen) were used for plasmid construction. These cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar plates supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Sigma) or 50 μg/ml kanamycin (Fisher BioReagents), when needed.

TABLE 1.

C. parapsilosis strains used in this study

| Strain | Strain background | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDC317 | NAa | NA | ATCC |

| Clinical isolates | |||

| CP3, CP5, CP13, CP23 | NA | Fluconazole susceptible | University of Iowa |

| CP1, CP2, CP4, CP6 to CP12, CP14 | NA | Fluconazole resistant | University of Iowa |

| CP22, CP24 to CP40 | |||

| Constructed laboratory strains | |||

| 29I23N1 | CP29 | mdr1Δ::FRT/mdr1Δ::FRT | This study |

| N1A2G3 | 29I23N1 | mdr1Δ::FRT/mdr1Δ::MDR1CP29-FRT | This study |

| 30B6A1 | CP30 | mdr1Δ::FRT/mdr1Δ::FRT | This study |

| A1B2G1 | 30B6A1 | mdr1Δ::FRT/mdr1Δ::MDR1CP30-FRT | This study |

| 36O3EE12 | CP36 | mdr1Δ::FRT/mdr1Δ::FRT | This study |

| EE12B4D1 | 36O3EE12 | mdr1Δ::FRT/mdr1Δ::MDR1CP36-FRT | This study |

| 35A1B1 | CP35 | cdr1Δ::FRT/cdr1Δ::FRT | This study |

| B1H2M10 | 35A1B1 | cdr1Δ::FRT/cdr1Δ::CDR1CP35-FRT | This study |

| 38A1B1 | CP38 | cdr1-1Δ::FRT/cdr1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| B1T4V1 | 38A1B1 | cdr1Δ::FRT/cdr1Δ::CDR1CP38-FRT | This study |

| 40B1G1 | CP40 | cdr1-1Δ::FRT/cdr1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| G1A2C12 | 40B1G1 | cdr1Δ::FRT/cdr1Δ::CDR1CP40-FRT | This study |

NA, not applicable.

Drug susceptibility testing.

Stock solutions of fluconazole were prepared by dissolving the drug in water to a concentration of 5 mg/ml. Stock solutions of both voriconazole and itraconazole were prepared by dissolving the drugs in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 640 μg/ml. MICs were obtained by performing broth microdilution, as described in CLSI document M27-A3 (19). Aliquots of 100 μl from the working drug stocks were used to inoculate a series of RPMI medium dilutions, the highest being 256 μg/ml for fluconazole and 8 μg/ml for both itraconazole and voriconazole. The cultures were incubated at 35°C, and MICs were recorded at 48 h.

Construction of plasmids.

All primers used are listed in Table 2. An MDR1 deletion construct was generated by amplifying an ApaI-XhoI-containing fragment consisting of flanking regions −822 to +116 relative to the start codon of MDR1 using primers MDR1-A and MDR1-B and a NotI-SacII-containing fragment of flanking region +1601 to +2463 using primers MDR1-C and MDR1-D. These upstream and downstream fragments of MDR1 were cloned on both sides of the SAT1 flipper cassette in plasmid pSFS2 (18) to result in plasmid p317MDR1. A CDR1 deletion construct was generated in a similar fashion. An ApaI-XhoI-containing fragment consisting of flanking regions −670 to +131 relative to the start codon of CDR1 was amplified using primers CDR1-A and CDR1-B, and a SacII-SacI-containing fragment consisting of flanking regions +4689 to +5219 was amplified using primers CDR1-C and CDR1-D. These upstream and downstream fragments of CDR1 were cloned on both sides of the SAT1 flipper cassette in plasmid pBSS2 to result in plasmid p317CDR1. The coding region of each gene was amplified with primers MDR1-A and MDR1-E or CDR1-A and CDR1-E. This ApaI-XhoI-containing fragment replaced the upstream sequence in cassettes p317MDR1 and p317CDR1 to reintroduce the native gene, creating plasmids pMDR1comp and pCDR1comp, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| qRT-PCR | |

| ACT1-F | 5′-TGGTTGGTATGGGTCAAA-3′ |

| ACT1-R | 5′-TGACGAAGCCCAATCA-3′ |

| ERG11-F | 5′-ATCAGCATCCACCAATGACG-3′ |

| ERG11-R | 5′-TCGTATTTCTAATTTGGTGG-3′ |

| CDR1-F | 5′-GCGTTTGACCATCGGAGTT-3′ |

| CDR1-R | 5′-AGATTCGCAAACAGC-3′ |

| MDR1-F | 5′-ATTGCCTCGGTGTTTCCAA-3′ |

| MDR1-R | 5′-CCTGTGGCTTGGGGTTCTC-3′ |

| Mutant construction | |

| MDR1-A | 5′-ATATTGCAACCAGCGGGCCCGGATATAAGT-3′ |

| MDR1-B | 5′-AGACTATGTCATTCTCGAGAAATATTTGAA-3′ |

| MDR1-C | 5′-GGGAATGGTCGCTATAGCGGCCGCATTTTATTTG-3′ |

| MDR1-D | 5′-GAGAGAAAGTGCCGCGGCCAGATATCACTA-3′ |

| MDR1-E | 5′-GAGAGAAAGTGCTCGAGCCAGATATCACTA-3′ |

| CDR1-A | 5′-GAAGTGGGGCCCATATGCATTAATTTTGTC-3′ |

| CDR1-B | 5′-CTGAACTGGTGTCTTCTCGAGTGTATGTTCTT-3′ |

| CDR1-C | 5′-AGAAACCGCGGTTTAGTCATTTGTTTTATT-3′ |

| CDR1-D | 5′-AATATCGGATGAGCTCAACTAGACTTTATC-3′ |

| CDR1-E | 5′-AATATCGGATGGTATCCTCGAGACTTTATC-3′ |

| Sequencing | |

| ERG11-A | 5′-CATACGACTGAGTTTCCCATCG-3′ |

| ERG11-B | 5′-GAAACAGAAAAGTGGCGTTGTTG-3′ |

| ERG11-C | 5′-GAGGACACCACGTATTGGTG-3′ |

| ERG11-D | 5′-CAACGAACATTCTGCATTAAACC-3′ |

| ERG11-E | 5′-GTAGTGGCACTAGTATGCTGTC-3′ |

| ERG11-F | 5′-CACGACATTGTTCAAAAAACCC-3′ |

| ERG3-A | 5′-CCCACGTTTATTTCACTAGATCC-3′ |

| ERG3-B | 5′-GGTTGCCTTGACCAACCC-3′ |

| ERG3-C | 5′-GTGTCCCTATTGCCCATTCCC-3′ |

| ERG3-D | 5′-GGGTTGGTCAAGGCAACC-3′ |

| UPC2-A | 5′-CCATCCTCAGAGTGAGAGACA-3′ |

| UPC2-B | 5′-GGACAGTTCGGTACCACCTG-3′ |

| UPC2-C | 5′-CTATGGCACAAGCAATGAATTCG-3′ |

| UPC2-D | 5′-CGAATATTTGCATTTCCGGCATTG-3′ |

| UPC2-E | 5′-GCCATTTGAAGTTGACCCACTAG-3′ |

| UPC2-F | 5′-CTAGTGGGTCAACTTCAAATGGC-3′ |

| UPC2-G | 5′-CCTTGGGAGTCCAAGTTGATG-3′ |

| UPC2-H | 5′-CGTTGAAGAGTTCAACCCATCC-3′ |

| TAC1-A | 5′-TGAACCATATCTGGGAGTTTAACAG-3′ |

| TAC1-B | 5′-GGATATGCACTGTATATCGGTACC-3′ |

| TAC1-C | 5′-GATGATGTCACAACCTGTACAGAG-3′ |

| TAC1-D | 5′-CGATTTTGCCAAACCCGATAAG-3′ |

| TAC1-E | 5′-CTAAACACCCCACTTGAGATGC-3′ |

| TAC1-F | 5′-CTTATCGGGTTTGGCAAAATCG-3′ |

| TAC1-G | 5′-CTCTGTACAGGTTGTGACATCATC - 3′ |

| TAC1-H | 5′-GGTACCGATATACAGTGCATATCC-3′ |

| MRR1-A | 5′-CTCGCTCTTACTTAAAGCGGAAATAC-3′ |

| MRR1-B | 5′-CCGGCTAATAAGCATCTCCAATTAG-3′ |

| MRR1-C | 5′-GAAGAAGAGTTTATCGAGTGGACGG-3′ |

| MRR1-D | 5′-GAGTGCTTGCAGGCAAATACATAC-3′ |

| MRR1-E | 5′-CATCAATTGGTGAATTCACCAAGGAG-3′ |

| MRR1-F | 5′-GAAAACAAGAAACACTGGGGTGG-3′ |

| MRR1-G | 5′-CTCCTTGGTGAATTCACCAATTGATG-3′ |

| MRR1-H | 5′-GTATGTATTTGCCTGCAAGCACTC-3′ |

| MRR1-I | 5′-CCGTCCACTCGATAAACTCTTCTTC-3′ |

| MRR1-J | 5′-CTAATTGGAGATGCTTATTAGCCGG-3′ |

Underlined segments indicate introduced restriction sites.

C. parapsilosis transformation.

C. parapsilosis strains were transformed by electroporation, as described previously, but with some modifications (18). Cells were grown for 6 h in 2 ml of YPD liquid medium, and then 4 μl of this cell suspension was passed to 50 ml of fresh YPD liquid medium and grown overnight at 30°C in a shaking incubator. When the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 2.0, cells were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of 10× Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, 1 ml of lithium acetate, and 8 ml of deionized water and then reincubated at 30°C for 1 h. Freshly prepared 1 M dithiothreitol was added to the cell suspension and reincubated for a further 30 min. Cells were then diluted with 40 ml of ice-cold water, pelleted at 4,000 rpm for 5 min, and washed twice, first with 25 ml of ice-cold sterile water and next with 5 ml of ice-cold 1 M sorbitol. Finally, the cells were resuspended in 100 μl of fresh ice-cold 1 mM sorbitol. A gel-purified ApaI-SacI fragment from the correct plasmid was mixed with 40 μl of competent cells and transferred into a chilled 2-mm electroporation cuvette. The reaction was carried out at 1.5 kV using a CelljecT Pro electroporator (Thermo). Immediately following, 1 ml of YPD containing 1 M sorbitol was added, and the mixture was transferred to a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube. Cells were allowed to recover at 30°C for 6 h. Finally, 100 μl was removed and plated to YPD agar plates containing 200 μg/ml nourseothricin and 1 M sorbitol. Transformants were selected after ≥48 h of growth at 30°C.

RNA isolation.

RNA was isolated using the hot phenol method of RNA isolation described previously (20). Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 and then incubated at 30°C with shaking for an additional 3 h to mid-log phase. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, liquid medium was poured off, and cells were frozen at −80°C for a minimum of 1 h. Next, cell pellets were resuspended in 900 μl of sodium acetate-EDTA buffer and then transferred to a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 950 μl of acid phenol (pH 4.3) and 80 μl of 20% SDS. Cells were incubated at 65°C for 10 min with occasional inversion mixing, placed on ice for a minimum of 5 min, and centrifuged. The supernatant was then transferred into a new tube containing 900 μl of chloroform and mixed. The sample was subjected to centrifugation again, and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube containing 1 ml of isopropanol and 100 μl of 2 M sodium acetate. This RNA pellet was washed with 500 μl of 70% ice-cold ethanol and collected by centrifugation. The RNA pellet was resuspended in DNase/RNase-free H2O. RNA concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and RNA integrity was verified using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies).

Reverse transcription-qualitative PCR.

cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Synthesized cDNA was used for both the amplification of ACT1 and the gene of interest by PCR, using SYBR green PCR master mix, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Gene-specific primers were designed using the Primer Express software synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies and are listed in Table 2. The PCR conditions consisted of AmpliTaq Gold activation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C. Software for the 7000 detection system (Applied Biosystems) was used to determine the dissociation curve and threshold cycle (CT). The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to calculate changes in gene expression among the isolates. All experiments included biological and technical replicates in triplicate. The standard error was calculated from the ΔCT values, as previously described (21).

Isolation of gDNA and Southern hybridization.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated, as described previously (22), and digested with an appropriate restriction endonuclease, separated on a 1% agarose gel, and, after staining with ethidium bromide, transferred by vacuum blotting to a nylon membrane and fixed by UV cross-linking. Southern hybridization with enhanced chemiluminescence-labeled probes was performed with the Amersham ECL Direct nucleic acid labeling and detection system, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequence analysis of individual genes.

Coding sequences from the genes of interest in C. parapsilosis were amplified by PCR from C. parapsilosis genomic DNA using the primers listed in Table 2. Products were cloned into pCR-BLUNTII-TOPO using a Zero Blunt TOPO PCR cloning kit and transferred into E. coli TOP10 cells with selection on LB agar plates containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Plasmid DNA was purified (Qiagen) and sequenced on an ABI model 3130xl genetic analyzer using sequencing primers, resulting in a full-length sequence from both strands of the C. parapsilosis gene of interest. The sequencing was performed using six sets of clones derived from three independent PCRs for each strain/isolate sequenced.

Sterol profiling.

Nonsaponifiable lipids were extracted using alcoholic KOH. Samples were dried in a vacuum centrifuge (Heto) and were derivatized by adding 100 μl of 90% N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA)–10% trimethylsilyl (TMS) (Sigma), 200 μl of anhydrous pyridine (Sigma), and heating for 2 h at 80°C. TMS-derivatized sterols were analyzed and identified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Thermo 1300 GC coupled to a Thermo ISQ mass spectrometer; Thermo Scientific) with reference to retention times and fragmentation spectra for known standards. GC-MS data files were analyzed using Xcalibur software (Thermo Scientific) to determine the sterol profiles for all isolates and for integrated peak areas (23).

RESULTS

Collection of clinical isolates and susceptibility testing.

Thirty-five unrelated fluconazole-resistant isolates and four susceptible isolates of C. parapsilosis were selected from a collection from the University of Iowa. These isolates vary in terms of source of infection, year of collection, country of origin, and demographics of the patients from which they were obtained. In accordance with the most recent CLSI guidelines for C. parapsilosis (19), resistance was defined as an MIC for fluconazole of ≥8 μg/ml and for voriconazole of ≥1 μg/ml. There are currently no interpretive guidelines for in vitro susceptibility testing of C. parapsilosis against itraconazole. The MICs were confirmed in our laboratory and are listed in Table 3. The 35 resistant isolates exhibited MICs for fluconazole ranging from 8 to 256 μg/ml. As expected, the four remaining isolates were susceptible to fluconazole, with MICs of 0.5 μg/ml, and none were susceptible dose dependent. Of the 39 total isolates, 14 isolates were susceptible to voriconazole, 13 were susceptible dose dependent, and the remaining 12 isolates were resistant to voriconazole, with MICs ranging from 1 to 8 μg/ml. The susceptibilities of all isolates to itraconazole ranged from 0.016 to 0.5 μg/ml.

TABLE 3.

Azole antifungal susceptibilities of the C. parapsilosis isolates in this collection

| Isolate | MIC (μg/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | Voriconazole | Itraconazole | |

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.0313 |

| 5 | 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.0625 |

| 13 | 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.0313 |

| 23 | 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.0625 |

| 21 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 |

| 1 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 6 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 8 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| 9 | 16 | 0.0313 | 0.125 |

| 10 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 11 | 16 | 0.0625 | 0.25 |

| 12 | 16 | 0.0625 | 0.25 |

| 15 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| 16 | 16 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| 17 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| 18 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| 19 | 16 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| 20 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 25 | 16 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 24 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 27 | 32 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| 31 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 64 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 14 | 64 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| 28 | 64 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 29 | 64 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 36 | 64 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| 39 | 64 | 1 | 0.25 |

| 7 | 128 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| 26 | 128 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 30 | 128 | 2 | 1 |

| 34 | 128 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 35 | 128 | 4 | 0.5 |

| 40 | 128 | 8 | 0.5 |

| 22 | 256 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 32 | 256 | 0.0313 | 0.125 |

| 37 | 256 | 4 | 0.5 |

| 38 | 256 | 4 | 0.5 |

Expression of ERG11, CDR1, and MDR1.

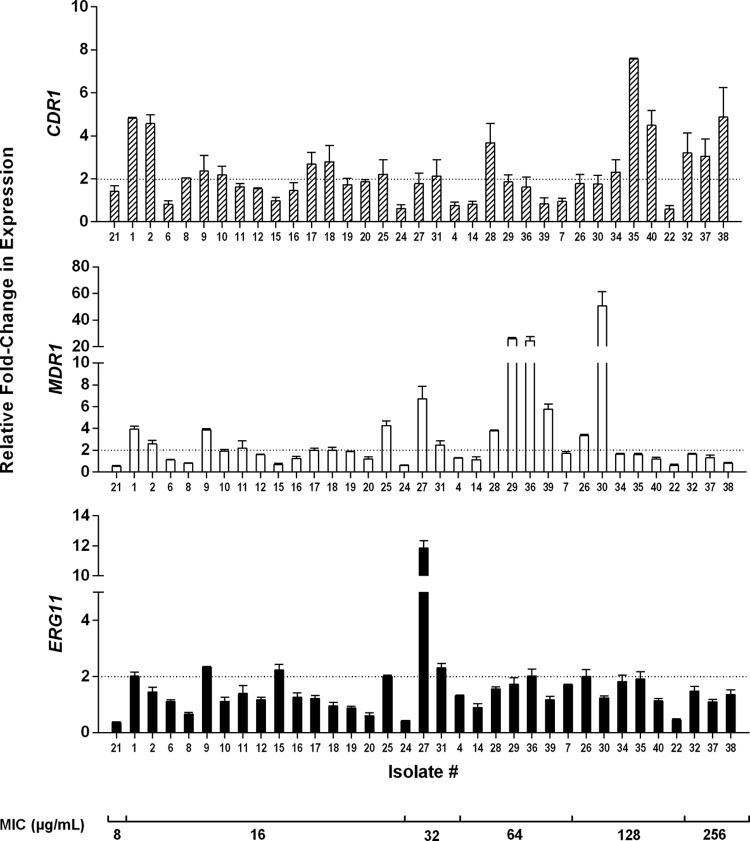

Orthologs of genes CaMDR1, CaCDR1, and CaERG11 were identified in C. parapsilosis by performing a BLAST search of these genes at the Candida Genome Database website, and the sequence with the highest homology to that of C. albicans was selected for primer creation. C. parapsilosis genes CPAR2_301760, CPAR2_405290, and CPAR2_303740 were identified as orthologs of MDR1, CDR1, and ERG11, respectively. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was used to determine whether transcript levels were increased in any resistant isolate compared to an average of those for the 4 susceptible isolates (Fig. 1). For the purposes of our investigation, we defined overexpression as a 2-fold increase in expression. For the four susceptible control isolates, the relative expression levels for CDR1, MDR1, and ERG11, compared to the average of those for these four isolates, ranged from 0.8- to 1.3-fold, 0.4- to 2.1-fold, and 0.3- to 1.8-fold, respectively. For the resistant isolates, we observed varied expression of both drug transporter genes among the isolates, with expression levels increased as much as 50-fold. More isolates showed CDR1 overexpression than MDR1 overexpression. Sixteen isolates showed a minimum of 2-fold increased expression of CDR1. These isolates exhibited a fluconazole MIC of ≥16 μg/ml. Isolates 29, 30, and 36 showed the highest expression levels of MDR1, with a minimum 25-fold increase; each exhibited an MIC of fluconazole of ≥64 μg/ml. Eight isolates exhibited a minimum of a 2-fold increase in C. parapsilosis ERG11 expression. These isolates ranged in susceptibility to fluconazole from 16 to 128 μg/ml. Notably, a single isolate (isolate 27) exhibited the highest expression level, with an 11-fold increase. This particular isolate exhibited a fluconazole MIC of 32 μg/ml.

FIG 1.

Relative fold change in expression of MDR1, CDR1, and ERG11 obtained from qRT-PCR for each resistant isolate of the collection. All experiments include biological and technical replicates in triplicate. Fold expression of the genes was compared to the average of the expression levels of the 4 susceptible isolates within the collection. The dotted line indicates a 2-fold relative change in gene expression. Error bars show standard errors. The isolates are listed in order of increasing MIC to fluconazole.

Sequencing of transcriptional regulators.

In C. albicans, activating mutations within transcriptional regulator genes UPC2, MRR1, and TAC1 led to the upregulation of target genes ERG11, MDR1, and CDR1, respectively, and in turn decreased fluconazole susceptibility (8, 9, 12–15). Therefore we questioned whether any of our ERG11-, MDR1-, or CDR1-overexpressing isolates contain single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the gene encoding its putative regulator. We identified the orthologs of CaTAC1, CaMRR1, and CaUPC2, in the manner described above, and determined their sequences in the isolates which overexpressed CDR1, MDR1, and ERG11, respectively, compared to those in the reference strain C. albicans CDC317. CPAR2_807270, CPAR2_303510, and CPAR2_207280 were identified as orthologs of MRR1, TAC1, and UPC2, respectively. Although ERG11 expression was observed to increase in eight of these isolates, among them, we found a single heterozygous UPC2 mutation in only a single isolate (isolate 36). While this mutation may influence Upc2 activity, these data suggest that activating mutations are not the mechanism by which ERG11 is overexpressed in most of these isolates and, unlike in C. albicans, this does not represent a common genetic mechanism of azole resistance in C. parapsilosis.

Among the 16 CDR1-overexpressing isolates, mutations leading to amino acid substitutions were detected in TAC1 in isolates 35, 38, and 40. Both isolates 35 and 38 contained the amino acid substitution G650E, whereas isolate 40 contained a heterozygous L978W substitution. None of these SNPs correspond to a documented activating mutation in CaTAC1. TAC1 mutations were not observed in the remaining 13 isolates that overexpress CDR1.

We know from C. albicans that overexpression of MDR1 must be quite high in order to impact azole susceptibility (24). Therefore, we focused on the 3 isolates (isolates 29, 30, and 36) that overexpressed MDR1 to the greatest degree for further evaluation. Mutations leading to amino acid substitutions were detected in MRR1 among MDR1-overexpressing isolates 29, 30, and 36. Isolate 29 contained an A854V substitution, isolate 30 contained an R479K substitution, and isolate 36 contained an I283R substitution. As was observed with TAC1, none of these SNPs corresponded to a documented activating mutation in CaMRR1 and, therefore, their direct role in constitutively activating the transcription of MRR1 in C. parapsilosis remains to be determined.

Targeted disruption of drug transporter genes.

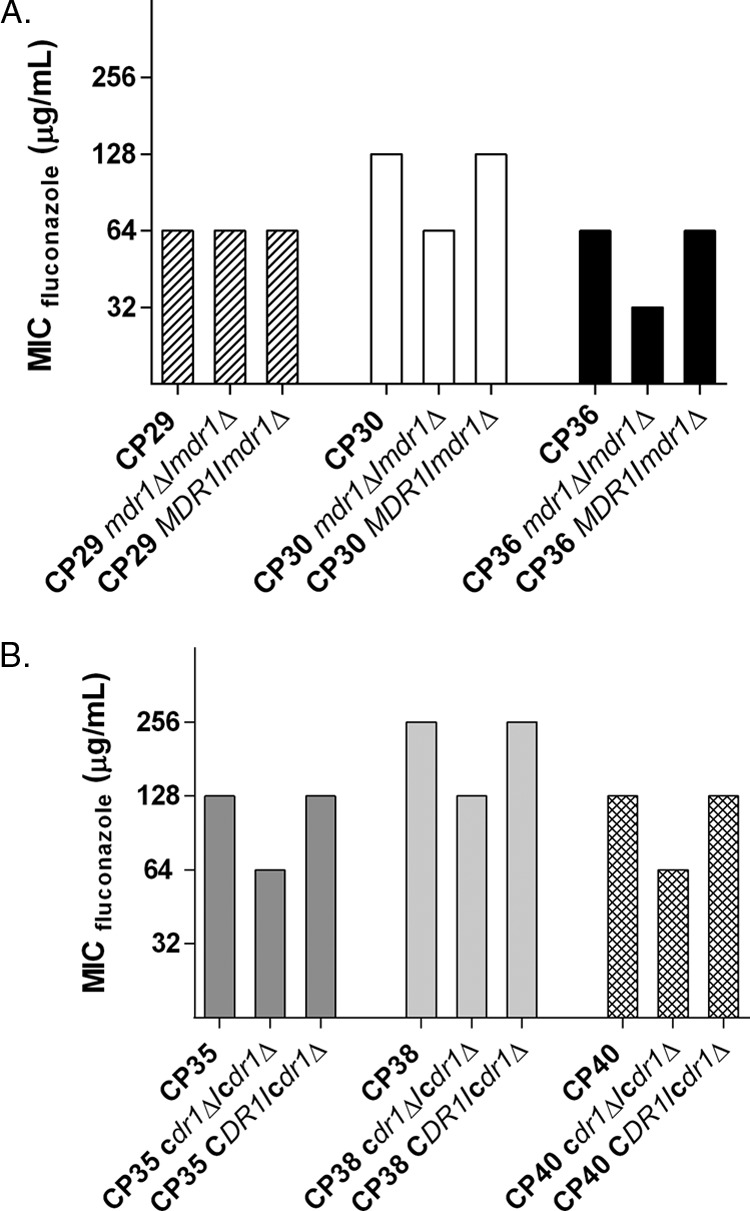

To determine if the putative drug transporters Mdr1 and Cdr1 directly contribute to azole resistance, we selected those isolates which overexpressed each drug transporter gene to the highest degree and deleted both alleles of the corresponding gene from those strains (Fig. 2). Two independent replicate mutant strains were created for each, and MICs were determined according to CLSI guidelines.

FIG 2.

Fluconazole MICs for isolates in which either Mdr1 (A) or Cdr1(B) have been deleted. Susceptibility testing was performed according to CLSI guidelines, and the 48-h MICs are reported here in micrograms per milliliter. The bars are grouped by a specific isolate, listing the wild-type isolate, the deletion mutant, and the complemented derivative isolate, respectively.

CDR1 was deleted in isolates 35, 38, and 40 and led to a 1-dilution decrease in fluconazole susceptibility in all 3 isolates. The fluconazole MIC for isolates 35 and 40 both dropped from 128 μg/ml to 64 μg/ml, and that for isolate 38 dropped from 256 μg/ml to 128 μg/ml. All phenotypes reverted upon complementation of the deleted alleles.

MDR1 was deleted from isolates 29, 30, and 36, and this conferred a reproducible 1-dilution decrease in fluconazole susceptibility in both isolates 30 and 36. The fluconazole MIC for isolate 30 dropped from 128 μg/ml to 64 μg/ml, and that for isolate 36 dropped from 64 μg/ml to 32 μg/ml. Isolate 29 showed no change in susceptibility upon MDR1 deletion; it maintained its fluconazole MIC of 64 μg/ml.

These data suggest that increased expression of MDR1 or CDR1 contributes only in part to the observed azole-resistant phenotype of these isolates, but it cannot completely explain the high levels of resistance observed. Therefore, other as-yet-undetermined mechanisms also impact azole resistance in these isolates.

Alterations in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway.

In C. albicans, alterations among genes in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway contribute to changes in azole susceptibility (25). In order to determine whether similar resistance mechanisms are operative among the 35 C. parapsilosis isolates within this collection, we sequenced both ERG11 and ERG3 in all isolates and compared the resulting sequences to the reference strain CDC317. We also acquired comprehensive sterol profiles by GC-MS for each isolate in order to determine whether alterations in sterol biosynthesis may be associated with azole resistance in these clinical isolates.

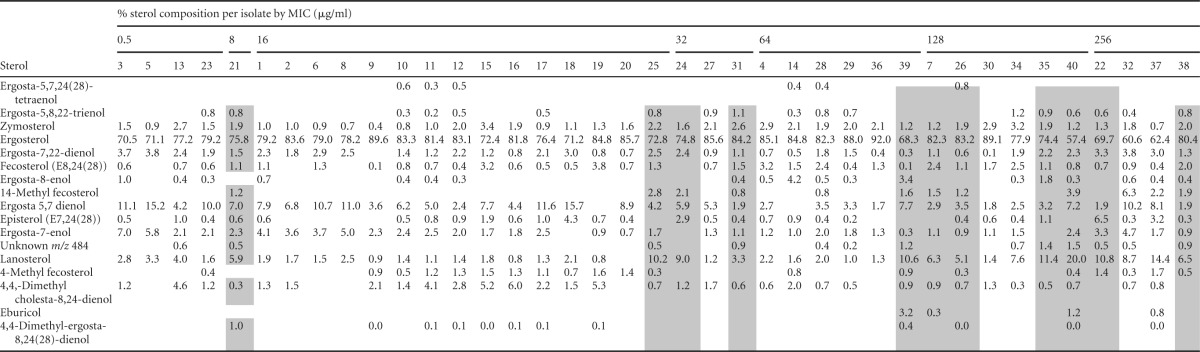

We found no mutations present in ERG3 among any isolate within the collection compared to the reference strain. This conclusion is supported by the sterol profile data, as no isolate exhibited increases in any sterol that would point to a change in the functionality of Erg3, namely, ergosta-7,22-dienol, episterol, and ergosta-7-enol. We did, however, observe three distinct SNPs in ERG11, S216L, Y132F, and R398I, within 16 of the isolates. As S216L was found in only one susceptible isolate, and R398I was identified in both susceptible and resistant isolates, we presume that these mutations alone do not contribute to azole resistance. The Y132F substitution, however, is present alone in only one of these resistant isolates, whereas it occurred together with the R398I substitution in 10 resistant isolates. Interestingly, nine of the 11 total isolates containing this amino acid substitution in ERG11 showed measurable levels of 14-methyl fecosterol, a sterol undetected in most isolates within this collection (Table 4). Additionally, these isolates exhibit increases in a sterol denoted to be either lanosterol or obtusifoliol; these are indistinguishable by our methodology of detection.

TABLE 4.

Sterol composition of C. parapsilosis isolatesa

Isolates containing ERG11 Y132F substitutions are indicated with gray shading.

We also observed additional variations within the sterol profiles of isolates within this collection. For example, isolates 4, 15, and 19 each exhibited increases in fecosterol, isolates 15 and 19 displayed higher than average levels of 4-methyl fecosterol, and isolate 4 exhibited an increase in fecosterol in addition to an increase in ergosterol. The significance of these alterations in sterol biosynthesis in the context of azole resistance remains to be determined (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

We reasoned that mechanisms of azole resistance operative in clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis would be similar to those observed in C. albicans. Therefore, we focused our efforts on the genes encoding the drug transporters Cdr1 and Mdr1, those encoding the sterol biosynthesis enzymes Erg11 and Erg3, and those encoding their transcriptional regulators Tac1, Mrr1, and Upc2. While similarities between these species were indeed observed, important and unexpected differences are apparent.

We found that both drug transporters Mdr1 and Cdr1 appear to play a modest role in azole resistance in C. parapsilosis. For Mdr1, this observation is consistent with what has been observed in C. albicans, in which the deletion of CaMDR1 in resistant isolates overexpressing this gene led to only a 1-dilution decrease in fluconazole susceptibility (14). The same was found to be true in the MDR1-overexpressing isolates of C. parapsilosis examined in the present study. We observed a marked overexpression of MDR1 in only three of the isolates in this collection. This is also consistent with our observations in a collection of azole-resistant isolates of C. albicans (9). We were, however, surprised that the deletion of CDR1 in isolates overexpressing this gene did not increase susceptibility to fluconazole to a greater degree, as has been observed in C. albicans (15). As amino acid substitutions in both regulators of these transporters, TAC1 and MRR1, are correlated with overexpression of their target genes, it is tempting to speculate that other targets of these regulators may contribute to azole resistance in these isolates.

As has been observed in C. albicans, ERG11 was found to be overexpressed in many of the azole-resistant clinical C. parapsilosis isolates in this collection. However, this does not appear to be mediated by activating mutations in UPC2. Only one isolate, isolate 36, contained a heterozygous mutation in UPC2. Unlike previously described CaUPC2 activating mutations, the substitution is not located in the C-terminal domain and therefore may not contribute to increased ERG11 expression (17). The mechanism by which this increased expression occurs is under investigation.

We sequenced both ERG3 and ERG11 in all isolates of this collection and found no amino acid substitutions in ERG3 in any isolate compared to the reference strain CDC317. The sterol profiles corroborate this finding. This azole resistance mechanism is considered uncommon in clinical isolates of C. albicans and, according to this analysis, the same might be concluded about C. parapsilosis. We did, however, identify 3 individual SNPs in the ERG11 gene leading to the S216L, R398I, and Y132F amino acid substitutions. The Y132F substitution was found in resistant isolates but not susceptible isolates. Amino acid position 132 is located in the predicated Erg11 catalytic site and most likely interacts with fluconazole. Furthermore, in C. albicans, its introduction into a susceptible strain reduces susceptibility to the azoles (17).

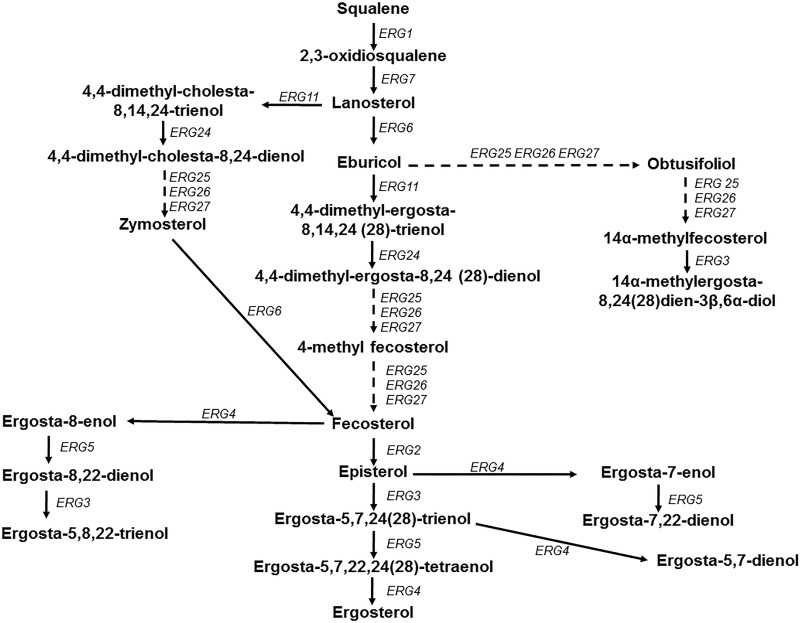

Interestingly, the sterol profiles of the isolates in this collection indicate that isolates that contain the Y132F substitution in ERG11 have higher than average levels of 14-methyl fecosterol. Increases in this sterol have been identified in Erg3-defective strains of C. albicans following Erg11 inhibition by azole treatment (26). It should be reiterated that the isolates in this study contain no mutation within the gene encoding Erg3, and the sterol profiles as a whole confirm this fact. These Y132F-containing isolates also showed a particularly high abundance of lanosterol/obtusifoliol compared to that of other isolates in the collection. This pattern suggests a potential bottleneck in sterol biosynthesis at the point of Erg11 in these isolates (Fig. 3). It is possible that Erg11 is altered in such a way by the Y132F mutation that the function of this enzyme has been compromised, forcing higher sterol turnover at the point of Erg25/Erg26/Erg27.

FIG 3.

Schematic representation of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway for Candida species. The solid arrows indicate a single enzymatic step, while the dashed arrows represent multiple enzymatic steps.

The low variability observed in the ERG11 sequence in this collection is both surprising and intriguing. We previously found 26 distinct amino acid substitutions in a collection of 63 fluconazole-resistant C. albicans clinical isolates (17). It is therefore somewhat unexpected that we observed only one Erg11 substitution associated with azole resistance in this collection of azole-resistant C. parapsilosis isolates. It is important to note that many azole-resistant C. albicans isolates in which ERG11 mutations have been identified are oral isolates, whereas the C. parapsilosis isolates in this collection were bloodstream isolates, for which higher doses of azoles are used and higher concentrations at the site of infection are achieved. Indeed, in C. albicans, the Y132F substitution was among the strongest individual mutations with regard to impact on fluconazole susceptibility, increasing the MIC of fluconazole from 0.5 μg/ml to 2 μg/ml (17). It is possible that weaker mutations fail to arise in the presence of azole concentrations achieved during the treatment of bloodstream infections. It is worthwhile to note that the ERG11 sequence for the reference strain CDC317 contains the Y132F substitution in Erg11, and the MIC of fluconazole for this strain is 4 μg/ml.

The remaining sterol data point to changes that may give insight into the ability of these isolates to cope with the effects of azole treatment. Isolate 4 has a relatively normal ergosterol abundance but a high fecosterol abundance. This might indicate a higher turnover through the enzymes upstream of fecosterol and less rapid consumption/conversion through the enzymes encoded by ERG2/3/4/5 (Fig. 3). Isolates 22 and 37 have larger than average amounts of 4-methyl fecosterol, with slight decreases in ergosterol abundance. This might indicate a bottleneck in the pathway around ERG25/26/27, leading to reduced ergosterol production. Whereas ergosta-8-enol is detected in quite small quantities in most isolates, its level is relatively high in isolate 39. Excess amounts of this sterol would be expected with impaired function of Erg2 (27). Whether this alteration in sterol composition is a consequence of a mutation in ERG2, and in turn impacts azole resistance, is not known.

A recent investigation of C. parapsilosis azole resistance mechanisms by Grossman et al. (16) also examined the sequences of ERG11 for the presence of amino acid substitutions. This group utilized the sequence of a different reference strain as the comparator, C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019. They identified the Y132F substitution as well and in fact observed it in 56.7% of their fluconazole-resistant isolates. They concluded that this mutation is perhaps largely responsible for most of the fluconazole resistance observed within this species. Our findings differ slightly with respect to frequency and in that we observed this polymorphism most frequently in combination with another substitution, R398I. The R398I substitution occurred alone in 1 susceptible isolate (isolate 3) and therefore does not appear to directly influence azole susceptibility. As this substitution is often observed in combination with the Y132F substitution, it is tempting to speculate that it may mitigate a cost in fitness that may occur in the presence of the Y132F substitution alone.

These data strongly indicate that known molecular mechanisms of resistance do not completely account for the azole resistance observed in this collection. Although it is likely that an individual isolate contains more than one mechanism, there is still insufficient cause for the high-level resistance observed for numerous isolates. This finding highlights the importance of continued investigation into the mechanisms of C. parapsilosis resistance to the azole drug class.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH NIAID grant R01 AI058145 awarded to P.D.R.

We thank Daniel J. Diekema for generously providing the clinical isolates used in this study and Qing Zhang for her assistance in the laboratory. We also thank Tom Cunningham in the Molecular Resource Center of Excellence at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diekema D, Arbefeville S, Boyken L, Kroeger J, Pfaller M. 2012. The changing epidemiology of healthcare-associated candidemia over three decades. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 73:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva AP, Miranda IM, Guida A, Synnott J, Rocha R, Silva R, Amorim A, Pina-Vaz C, Butler G, Rodrigues AG. 2011. Transcriptional profiling of azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3546–3556. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01127-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockhart SR, Iqbal N, Cleveland AA, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Bolden CB, Baughman W, Stein B, Hollick R, Park BJ, Chiller T. 2012. Species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida bloodstream isolates from population-based surveillance studies in two U.S. cities from 2008 to 2011. J Clin Microbiol 50:3435–3442. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01283-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. 2010. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit Rev Microbiol 36:1–53. doi: 10.3109/10408410903241444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Asbeck EC, Clemons KV, Stevens DA. 2009. Candida parapsilosis: a review of its epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical aspects, typing and antimicrobial susceptibility. Crit Rev Microbiol 35:283–309. doi: 10.3109/10408410903213393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trofa D, Gácser A, Nosanchuk JD. 2008. Candida parapsilosis, an emerging fungal pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:606–625. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK Jr, Calandra TF, Edwards JE Jr, Filler SG, Fisher JF, Kullberg BJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 48:503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacPherson S, Akache B, Weber S, De Deken X, Raymond M, Turcotte B. 2005. Candida albicans zinc cluster protein Upc2p confers resistance to antifungal drugs and is an activator of ergosterol biosynthetic genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:1745–1752. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1745-1752.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flowers SA, Barker KS, Berkow EL, Toner G, Chadwick SG, Gygax SE, Morschhauser J, Rogers PD. 2012. Gain-of-function mutations in UPC2 are a frequent cause of ERG11 upregulation in azole-resistant clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 11:1289–1299. doi: 10.1128/EC.00215-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warrilow AG, Martel CM, Parker JE, Melo N, Lamb DC, Nes WD, Kelly DE, Kelly SL. 2010. Azole binding properties of Candida albicans sterol 14-alpha demethylase (CaCYP51). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:4235–4245. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00587-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly SL, Lamb DC, Kelly DE, Manning NJ, Loeffler J, Hebart H, Schumacher U, Einsele H. 1997. Resistance to fluconazole and cross-resistance to amphotericin B in Candida albicans from AIDS patients caused by defective sterol delta5,6-desaturation. FEBS Lett 400:80–82. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanglard D, Kuchler K, Ischer F, Pagani JL, Monod M, Bille J. 1995. Mechanisms of resistance to azole antifungal agents in Candida albicans isolates from AIDS patients involve specific multidrug transporters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:2378–2386. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.11.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Ribot JL, McAtee RK, Lee LN, Kirkpatrick WR, White TC, Sanglard D, Patterson TF. 1998. Distinct patterns of gene expression associated with development of fluconazole resistance in serial Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:2932–2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morschhäuser J, Barker KS, Liu TT, BlaB-Warmuth J, Homayouni R, Rogers PD. 2007. The transcription factor Mrr1p controls expression of the MDR1 efflux pump and mediates multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 3:e164. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coste A, Turner V, Ischer F, Morschhäuser J, Forche A, Selmecki A, Berman J, Bille J, Sanglard D. 2006. A mutation in Tac1p, a transcription factor regulating CDR1 and CDR2, is coupled with loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 5 to mediate antifungal resistance in Candida albicans. Genetics 172:2139–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grossman NT, Pham CD, Cleveland AA, Lockhart SR. 2014. Molecular mechanisms of fluconazole resistance in Candida parapsilosis isolates from a U.S. surveillance system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1030–1037. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04613-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flowers SA, Colón B, Whaley SG, Schuler MA, Rogers PD. 2015. Contribution of clinically derived mutations in ERG11 to azole resistance in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:450–460. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03470-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reuss O, Vik A, Kolter R, Morschhäuser J. 2004. The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 341:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard—3rd ed CLSI document M27-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt ME, Brown TA, Trumpower BL. 1990. A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 18:3091–3092. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.10.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunkel N, Liu TT, Barker KS, Homayouni R, Morschhäuser J, Rogers PD. 2008. A gain-of-function mutation in the transcription factor Upc2p causes upregulation of ergosterol biosynthesis genes and increased fluconazole resistance in a clinical Candida albicans isolate. Eukaryot Cell 7:1180–1190. doi: 10.1128/EC.00103-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amberg DC, Burke DJ, Strathern JN. 2006. Isolation of yeast genomic DNA for Southern blot analysis. CSH Protoc 2006:pdb.prot4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly SL, Lamb DC, Corran AJ, Baldwin BC, Kelly DE. 1995. Mode of action and resistance to azole antifungals associated with the formation of 14 alpha-methylergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3 beta,6 alpha-diol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 207:910–915. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiller D, Sanglard D, Morschhäuser J. 2006. Overexpression of the MDR1 gene is sufficient to confer increased resistance to toxic compounds in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1365–1371. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1365-1371.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White TC, Marr KA, Bowden RA. 1998. Clinical, cellular, and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 11:382–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson PF, Rose ME, Ellis SW, England H, Kelly SL. 1989. Defective sterol C5-6 desaturation and azole resistance: a new hypothesis for the mode of action of azole antifungals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 164:1170–1175. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(89)91792-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hull CM, Bader O, Parker JE, Weig M, Gross U, Warrilow AG, Kelly DE, Kelly SL. 2012. Two clinical isolates of Candida glabrata exhibiting reduced sensitivity to amphotericin B both harbor mutations in ERG2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:6417–6421. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01145-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]