Abstract

The 4-aminoquinoline naphthoquine (NQ) and the thiazine dye methylene blue (MB) have potent in vitro efficacies against Plasmodium falciparum, but susceptibility data for P. vivax are limited. The species- and stage-specific ex vivo activities of NQ and MB were assessed using a modified schizont maturation assay on clinical field isolates from Papua, Indonesia, where multidrug-resistant P. falciparum and P. vivax are prevalent. Both compounds were highly active against P. falciparum (median [range] 50% inhibitory concentration [IC50]: NQ, 8.0 nM [2.6 to 71.8 nM]; and MB, 1.6 nM [0.2 to 7.0 nM]) and P. vivax (NQ, 7.8 nM [1.5 to 34.2 nM]; and MB, 1.2 nM [0.4 to 4.3 nM]). Stage-specific drug susceptibility assays revealed significantly greater IC50s in parasites exposed at the trophozoite stage than at the ring stage for NQ in P. falciparum (26.5 versus 5.1 nM, P = 0.021) and P. vivax (341.6 versus 6.5 nM, P = 0.021) and for MB in P. vivax (10.1 versus 1.6 nM, P = 0.010). The excellent ex vivo activities of NQ and MB against both P. falciparum and P. vivax highlight their potential utility for the treatment of multidrug-resistant malaria in areas where both species are endemic.

INTRODUCTION

Early diagnosis and effective treatment of malaria are central to the success of malaria control programs. However, this strategy is compromised by the emergence of drug-resistant parasites that are well established in Plasmodium falciparum and increasingly recognized in P. vivax (1, 2). The emergence of multidrug-resistant parasites throughout the regions of the world where malaria is endemic has been a driving force in the development and deployment of a variety of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT) for the treatment of falciparum malaria (3). Endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), ACT is now the first-line antimalarial treatment in more than 80 countries. Although chloroquine (CQ) remains the treatment of choice for vivax malaria, this position is increasingly under threat from the emergence and spread of CQ-resistant P. vivax strains that, in some areas, have reached high levels, requiring the revision of national guidelines (2).

The ability of parasites to develop resistance to antimalarial drugs is relentless, as evidenced by reports of the emergence and spread of decreased in vivo and in vitro susceptibility to most antimalarial agents, including the artemisinin derivatives (4, 5) and ACT (6, 7). It is imperative that the development of new and effective partner drugs is maintained to ensure an armamentarium of highly effective antimalarial treatments.

Naphthoquine phosphate (NQ), a 4-aminoquinoline compound first synthesized in China in the 1980s, demonstrates excellent efficacy against the murine malaria parasite P. berghei and CQ-resistant P. falciparum (8–10). NQ has been combined with artemisinin as a fixed-dose combination therapy (ARCO) with proven in vivo efficacy against falciparum (11–13) and vivax malaria (14–16). Although approved and registered in more than 10 countries, in vitro NQ susceptibility data in clinical isolates of P. falciparum are limited, with no published ex vivo data yet available for P. vivax.

The antimalarial activity of the thiazine dye methylene blue (MB) was first reported at the end of the 19th century (17). Although MB's antimalarial efficacy has been proven in several studies over the next decades, MB was abandoned from the drug development pipeline due to its low tolerability, which was the result of unpleasant, but reversible, adverse effects (18). There is renewed interest in the use of MB in the modern era of malaria therapeutics, with studies highlighting its potent schizonticidal activity against CQ-resistant P. falciparum (19–24) and gametocytocidal activity (25–27). Furthermore, clinical trials in Africa have shown that effective antiplasmodial doses of MB are safe in both adults and children, including glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)-deficient individuals (28, 29). MB has also been shown to have ex vivo activity against CQ-sensitive P. vivax (30) but has yet to be assessed against CQ-resistant P. vivax.

The objectives of the current study were to examine the species- and stage-specific ex vivo susceptibilities of NQ and MB in clinical field isolates of Plasmodium from an area with known multidrug resistance in P. falciparum and P. vivax and to define the cross-susceptibility patterns between NQ and MB and conventional antimalarials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Field location and sample collection.

Plasmodium isolates were collected from patients attending malaria clinics in Timika (Papua, Indonesia), a region known to be endemic for P. falciparum isolates resistant to CQ, amodiaquine (AQ), and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), and P. vivax isolates resistant to CQ (31–33). Unpublished clinical data from 2015 suggest that dihydroartemisinin (DHA) and piperaquine (PIP) retain high efficacy against both Plasmodium species. Patients with symptomatic malaria were recruited into the study if they were singly infected with P. falciparum or P. vivax, with a parasitemia of between 2,000 μl−1 and 80,000 μl−1, and the majority (>70%) of parasites at the ring stage of development. After written consent was obtained, venous blood samples (5 ml) were collected and after removal of host white blood cells by using cellulose filters, the packed infected red blood cells (iRBCs) were used for the ex vivo drug susceptibility assay.

Ex vivo drug susceptibility assay.

Drug plates were predosed with the standard antimalarials CQ, AQ, PIP, mefloquine (MFQ), and artesunate (AS) (WWARN QA/QC Reference Material Programme) (34) plus NQ (MMV17; Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland, on behalf of Medicines for Malaria Venture [MMV]) and MB (Sigma-Aldrich, Australia).

The drug susceptibility of P. vivax and P. falciparum isolates was measured using a protocol modified from the WHO microtest as described previously (33, 35, 36). In brief, 200 μl of a 2% hematocrit blood media mixture (BMM), consisting of RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% AB+ human serum (P. falciparum) or McCoy's 5A medium plus 20% AB+ human serum (P. vivax) was added to each well of predosed drug plates containing 11 serial concentrations (2-fold dilutions) of the antimalarials (maximum concentration shown in parentheses) CQ (2,993 nM), AQ (158 nM), PIP (1,029 nM), MFQ (338 nM), AS (49 nM), NQ (481 nM), and MB (51 nM). A candle jar was used to mature the parasites at 37.0°C for 35 to 56 h. Incubation was stopped when >40% of the ring-stage parasites had reached the mature schizont stage in the drug-free control wells.

Thick blood films made from each well were stained with 5% Giemsa solution for 30 min and examined microscopically. The number of schizonts per 200 asexual stage parasites was determined for each drug concentration and normalized to the control well.

To investigate the stage-specific drug susceptibility of antimalarial action, a subgroup of isolates with >90% ring-stage parasites initially was exposed to the drugs for 24 h. The iRBCs were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline using centrifugation and were resuspended in drug-free medium and cultured for another 20 to 24 h before harvest (i.e., ring-stage assay). The same isolate was cultured for 20 to 24 h in the absence of drugs until 85 to 95% of parasites had reached the trophozoite stage; these were then drug exposed for 24 h until harvest (trophozoite stage assay) (33, 37).

Quality control procedures.

Microscopy quality control was ensured by randomly selecting recordings for two drugs per isolate which were read by a second microscopist. If the raw data derived by the two microscopists led to a significant shift in the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) estimates of the selected drugs (i.e., more than one dilution difference), the whole assay (i.e., all standard drugs and experimental compounds) was reread by a second reader, and the results were compared. Discrepant results were resolved by a third reading by an expert microscopist. Drug plate quality was ensured by testing drug plates using the same methodology with P. falciparum laboratory strains K1 and FC27.

Data analysis.

The dose-response data were analyzed using nonlinear regression analysis (WinNonlin 4.1; Pharsight Corporation), and the IC50s were derived using an inhibitory sigmoid Emax model. Ex vivo IC50 data were only used from predicted curves where the maximum effect (Emax) and E0 were within 15% of 100 and 1, respectively. Data analysis was performed using STATA (version 13.1) and GraphPad Prism (version 6). The Mann-Whitney U test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and Spearman rank correlation were used for nonparametric comparisons and correlations.

Ethical approval.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Eijkman Institute Research Ethics Commission, the Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology, Jakarta, Indonesia, and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory (NT) Department of Health and Families and Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin, Australia.

RESULTS

Drug susceptibility.

A total of 147 clinical isolates from patients with single-species infections of either P. falciparum (n = 80) or P. vivax (n = 67) were assessed. The standard antimalarials were assayed for all isolates and NQ was assayed in 63 isolates (25 P. falciparum and 38 P. vivax) between June and October 2011 and again between June and September 2013. MB was tested in 113 isolates (63 P. falciparum and 50 P. vivax) between January and September 2013. NQ and MB were tested in parallel in only 8 P. falciparum and 21 P. vivax isolates. Adequate growth for harvest was achieved in 84% (21/25) of P. falciparum and 76% (29/38) of P. vivax isolates in which NQ was tested and in 83% (52/63) of P. falciparum and 82% (41/50) of P. vivax isolates in which MB was tested. The baseline characteristics of the isolates processed are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of isolates for which ex vivo assays were performed

| Baseline characteristic | Naphthoquine |

Methylene blue |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum (n = 25) | P. vivax (n = 38) | P. falciparum (n = 63) | P. vivax (n = 50) | |

| Isolates reaching harvest (no. [%]) | 21 (84.00) | 29 (76.32) | 52 (82.54) | 41 (82.00) |

| Delay from venepuncture to start of culture (median [range]) (min) | 160 (85–310) | 178 (55–330) | 125 (60–310) | 148 (55–330) |

| Duration of assay (median [range]) (h) | 44 (32–48) | 47 (42–50) | 45 (32–50) | 46 (32–50) |

| Parasitemia (geometric mean [95% CIa]) (asexual parasites/μl) | 24,102 | 25,001 | 13,343 | 22,454 |

| (15,856–36,637) | (17,487–35,742) | (11,059–16,099) | (16,531–30,501) | |

| Parasites at ring stage initially (median [range]) (%) | 100b | 96 (71–99) | 100b | 96 (70–99) |

| Schizont count at harvest (mean [range]) (%) | 50 (16–76) | 45 (13–70) | 42 (14–75) | 43 (13–70) |

CI, confidence interval.

No range given (all values were 100%).

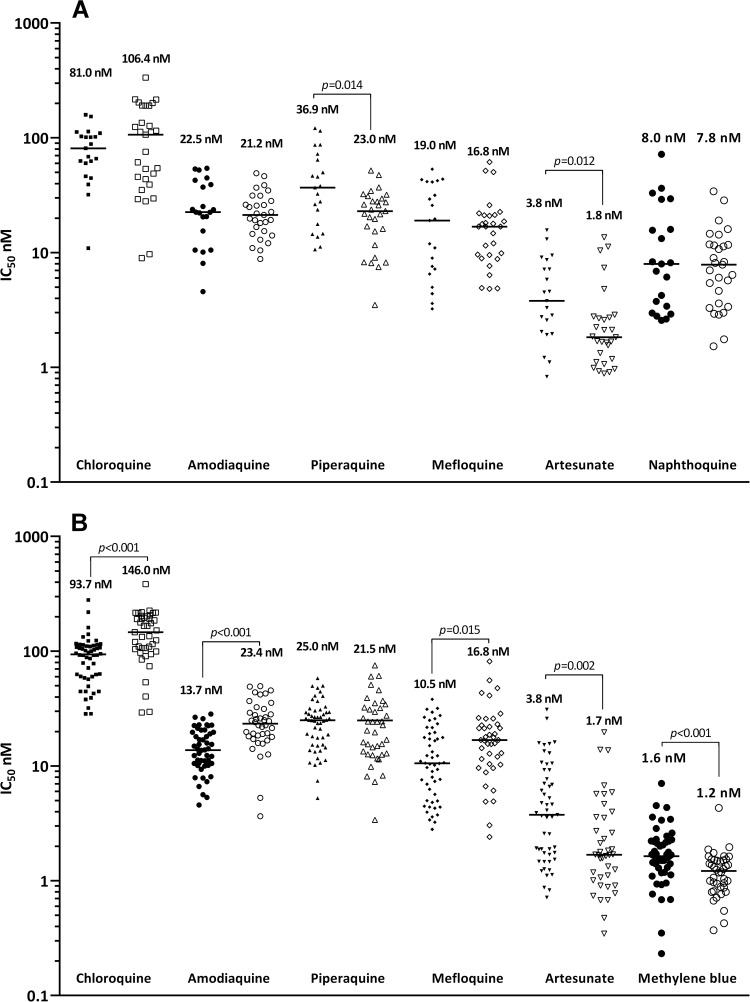

The IC50s for isolates which were successfully cultured and the comparison with IC50s for P. falciparum laboratory strains FC27 and K1 are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Although NQ and MB were tested on different drug plate lots, quality control experiments using laboratory strains and the same assay method showed no differences between drug plate lots for either the standard antimalarials or the test compounds NQ and MB. In the MB group, the median IC50s in P. falciparum were significantly higher than those of P. vivax for AS (3.8 versus 1.7 nM, P = 0.002) and MB (1.6 versus 1.2 nM, P < 0.001), but lower than those for CQ (93.7 nM versus 146.0, P < 0.001), AQ (13.7 versus 23.4 versus, P < 0.001), and MFQ (10.5 nM versus 16.8, P = 0.015).

TABLE 2.

Ex vivo drug susceptibility for each drug according to the species tested

| Drug |

P. falciparum laboratory linesa |

P. falciparum clinical field isolates |

P. vivax clinical field isolates |

Pb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC27 (CQs) | K1 (CQr) | No. (%)c | Median (range) IC50 (nM) | Pd | No. (%)c | Median (range) IC50 (nM) | Pd | ||

| CQ | 24.1 | 140.5 | 21 (100) | 80.9 (10.9–158.7) | <0.001 | 29 (100) | 106.4 (9.0–334.6) | <0.001 | 0.485 |

| AQ | 20.3 | 26.9 | 21 (100) | 22.5 (4.6–54.2) | <0.001 | 29 (100) | 21.2 (8.8–49.2) | <0.001 | 0.549 |

| PIP | 31.7 | 47.2 | 21 (100) | 36.9 (10.6–121.2) | <0.001 | 29 (100) | 23.0 (3.5–51.9) | <0.001 | 0.014 |

| MFQ | 53.8 | 13.7 | 21 (100) | 19.0 (3.2–53.3) | 0.030 | 29 (100) | 16.8 (4.9–61.5) | <0.001 | 0.791 |

| AS | 10.1 | 7.7 | 21 (100) | 3.8 (0.8–15.7) | [0.001] | 29 (100) | 1.8 (0.9–13.5) | [0.001] | 0.012 |

| NQ | 13.1 | 15.3 | 21 (100) | 8.0 (2.6–71.8) | 29 (100) | 7.8 (1.5–34.2) | 0.7015 | ||

| CQ | 16.3 | 121.4 | 52 (100) | 93.7 (28.4–279.0) | <0.001 | 41 (100) | 146.0 (29.2–383.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AQ | 14.2 | 21.3 | 50 (96) | 13.7 (4.6–28.3) | <0.001 | 40 (98) | 23.4 (3.7–49.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PIP | 45.9 | 38.1 | 52 (100) | 25.0 (5.2–58.1) | <0.001 | 40 (98) | 21.5 (3.4–75.3) | <0.001 | 0.440 |

| MFQ | 72.0 | 16.3 | 52 (100) | 10.5 (2.8–38.0) | <0.001 | 41 (100) | 16.8 (2.4–81.4) | <0.001 | 0.015 |

| AS | 9.7 | 5.1 | 51(100) | 3.8 (0.7–31.0) | <0.001 | 40 (98) | 1.7 (0.4–19.7) | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| MB | 7.2 | 5.7 | 51 (100) | 1.6 (0.2–7.0) | 40 (98) | 1.2 (0.4–4.3) | <0.001 | ||

Mean IC50s (derived from three independent experiments) were assessed by in vitro schizont maturation quantified by microscopy. CQs, chloroquine-sensitive laboratory strain; CQr, chloroquine-resistant laboratory strain.

Significant difference in median drug IC50s between species (Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Total number of assays with acceptable IC50s (percentage of samples which fulfilled the criteria for successful culture).

Comparison of each drug (Wilcoxon rank sum test) with either NQ (top) or MB (bottom).

FIG 1.

Ex vivo drug susceptibility (median IC50s) to standard antimalarials, NQ (A) and MB (B) in P. falciparum (closed symbols) and P. vivax (open symbols) clinical isolates (P, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

NQ showed very potent activities against both species (8.0 nM in P. falciparum and 7.8 nM in P. vivax), and its activity was significantly higher than the activities of all of the standard antimalarials tested, with the exception of AS. MB exhibited excellent activities (median IC50s of 1.6 nM against P. falciparum and 1.2 nM against P. vivax), exceeding the activities of all standard antimalarials tested, including the artemisinin derivative AS (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Stage-specific drug activity.

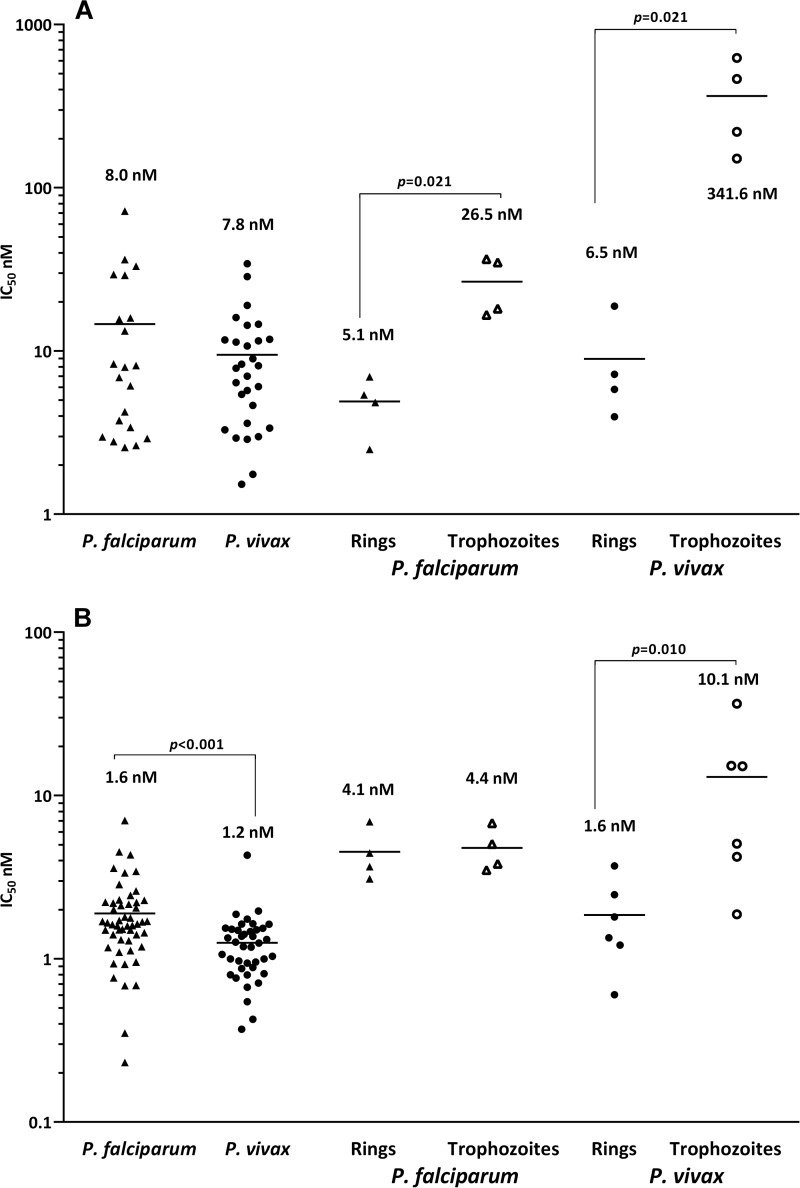

In P. vivax isolates, the median IC50s of all drugs were significantly higher at the trophozoite stage than at the ring stage, the ratio being 1.5- to 8-fold higher for the standard antimalarials and MB and 50-fold higher for NQ (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The difference in stage specificity was much less in P. falciparum isolates, with significance reached only for PIP (21.9 nM for rings versus 128.2 nM for trophozoites; P = 0.045) and NQ (5.1 nM versus 26.5 nM; P = 0.021).

TABLE 3.

Ex vivo susceptibilities for paired isolates exposed for 24 h at the ring and trophozoite stages

| Drug |

P. falciparum |

P. vivax |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.a | Median (range) IC50 (nM) |

Pb | No.a | Median (range) IC50 (nM) |

Pb | |||

| Rings | Trophozoites | Rings | Trophozoites | |||||

| CQ | 6 | 107.9 (60.2–163.6) | 142.7 (25.5–163.6) | 0.855 | 11 | 81.7 (27.6–190.2) | 705.6 (99.9–4,033.3) | <0.001 |

| AQ | 7 | 16.2 (4.9–20.8) | 18.0 (7.8–25.4) | 0.570 | 11 | 20.0 (2.1–39.5) | 47.7 (7.6–89.8) | 0.031 |

| PIP | 6 | 21.9 (7.8–33.3) | 128.2 (13.8–359.3) | 0.045 | 11 | 18.0 (3.5–69.6) | 30.3 (18.1–204.5) | 0.042 |

| MFQ | 7 | 15.3 (4.7–46.9) | 17.3 (4.6–30.6) | 0.570 | 11 | 21.4 (4.9–41.0) | 34.9 (11.7–85.5) | 0.042 |

| AS | 6 | 2.1 (0.7–5.1) | 3.9 (1.3–8.1) | 0.584 | 11 | 1.9 (0.9–5.7) | 7.2 (0.8–19.3) | 0.045 |

| NQ | 4 | 5.1 (2.5–7.0) | 26.5 (16.6–36.5) | 0.021 | 4 | 6.5 (4.0–18.8) | 341.6 (150.8–622.6) | 0.021 |

| MB | 4 | 4.1 (3.1–6.9) | 4.4 (3.5–6.8) | 0.773 | 6 | 1.6 (0.6–3.7) | 10.1 (1.9–36.5) | 0.010 |

Number of paired isolates.

Comparison of drugs tested at the ring and trophozoite stages.

FIG 2.

Ex vivo drug susceptibility (median IC50s) for NQ (A) and MB (B) according to the species tested and for paired ring-stage (closed symbols) versus trophozoite-stage (open symbols) parasites (P, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Cross-susceptibility patterns.

Growth inhibition by NQ was strongly correlated in P. falciparum and P. vivax isolates with AQ, PIP, and MFQ but only with CQ in P. vivax and with AS in P. falciparum isolates (Table 4). For MB, moderate correlations were observed for CQ, AQ, PIP, and MFQ in P. falciparum but not in P. vivax isolates.

TABLE 4.

Correlation of ex vivo antimalarial susceptibilities in P. falciparum and P. vivax clinical field isolatesa

| Antimalarial combination |

P. falciparum |

P. vivax |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | P | df | rs | P | df | |

| NQ-CQ | 0.179 | 0.437 | 21 | 0.528 | 0.003 | 28 |

| NQ-AQ | 0.583 | 0.006 | 21 | 0.418 | 0.024 | 28 |

| NQ-PIP | 0.607 | 0.004 | 21 | 0.413 | 0.026 | 27 |

| NQ-MFQ | 0.495 | 0.023 | 21 | 0.380 | 0.042 | 28 |

| NQ-AS | 0.609 | 0.003 | 21 | 0.015 | 0.937 | 28 |

| MB-CQ | 0.422 | 0.002 | 51 | 0.021 | 0.900 | 40 |

| MB-AQ | 0.393 | 0.005 | 50 | −0.105 | 0.520 | 40 |

| MB-PIP | 0.385 | 0.005 | 51 | 0.116 | 0.481 | 39 |

| MB-MFQ | 0.327 | 0.020 | 51 | 0.021 | 0.897 | 40 |

| MB-AS | 0.170 | 0.239 | 50 | 0.107 | 0.516 | 39 |

rs, Spearman rank correlation; df, degrees of freedom.

DISCUSSION

The current study highlights the potent ex vivo activities of NQ and MB against multidrug-resistant isolates of P. falciparum and P. vivax. The IC50s of NQ in P. falciparum isolates (median IC50, 8.0 nM; interquartile range, 26.5 nM) were similar to those reported in culture-adapted P. falciparum isolates from Papua New Guinea (geometric mean, 7.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 5.5 to 8.8 nM) (38). Our ex vivo study presents additional evidence for NQ's potent activities against highly CQ-resistant isolates of P. falciparum and P. vivax, revealing lower IC50s for NQ than for all of the standard drugs with the exception of AS. The ex vivo activity of MB was greater than that of NQ, in line with previous observations in P. falciparum (19–24, 39) and P. vivax (30), with lower IC50s than those for all standard drugs, including AS, for both species.

Interspecies comparisons of drug susceptibilities revealed slightly different patterns in the two subgroups of isolates. Although these observations might suggest underlying species differences in pharmacodynamic activity, the differences were of marginal magnitude and may also reflect statistical chance.

Positive correlations of drug susceptibilities are potentially indicative of either similar modes of action of these drugs or similar pharmacokinetic properties. Alternatively, they can represent acquired resistance on the background of previous antimalarial resistance phenotypes. Previous studies of P. falciparum have documented positive correlations between the IC50s for the quinoline class of compounds and related drugs (38, 40). The correlation of NQ with AQ, PIP, MFQ, and AS observed in P. falciparum isolates in the present study was similar to that reported from neighboring Papua New Guinea (38). Surprisingly, we observed no correlation between NQ and CQ IC50s in P. falciparum. However, in P. vivax isolates, NQ IC50s were positively correlated with those of all the quinoline-based drugs, but not AS. In contrast, the only significant correlations for MB were with CQ, AQ, and PIP in P. falciparum, a pattern similar to that observed in previous studies (22, 24). MB's parasitocidal activity is postulated to be mediated by the inhibition of heme polymerization (39, 41) and glutathione reductase in P. falciparum (42, 43). Assuming a similar mode of cytotoxicity in P. vivax, the contrasting correlation most likely indicates differences in drug uptake and partition between the two species.

We observed a marked stage-specific action for NQ. Compared to parasites at the ring stage, the trophozoites of both P. falciparum and P. vivax were resistant to NQ, with 5-fold and 50-fold higher IC50s, respectively. The stage specificity was less apparent for MB, only reaching significance for P. vivax trophozoites, which had 6-fold higher IC50s than ring stages. The findings for NQ are at odds with previous data for other conventional antimalarials such as CQ and AQ, which manifest a far greater difference in stage-specific activity for P. vivax, although the number of isolates tested was small (33, 37). Further studies are needed to validate these findings and investigate the phenomenon of innate versus acquired drug tolerance in Plasmodium.

The potent NQ ex vivo activity demonstrated against both P. falciparum and P. vivax suggests that NQ may be a suitable candidate as an ACT partner drug in regions where these species are coendemic. NQ combined with artemisinin derivatives has achieved adequate clinical efficacy against falciparum malaria (11–13), as well as against CQ-sensitive and CQ-resistant vivax malaria (14–16). However, concerns have been raised that the currently available single-dose regimen (ARCO) provides inadequate reduction of the early parasite biomass, leaving the more slowly eliminated NQ vulnerable to the selection of drug resistance. Our data demonstrate a correlation in antimalarial activity with that of the other 4-aminoquinolines and, together with a report of the induction of NQ resistance in an experimental rodent model (8), highlight the importance of close monitoring of drug efficacy, particularly in areas where quinoline-based ACTs have been in widespread use.

The current study also confirms MB's remarkable ex vivo efficacy against resistant strains of P. falciparum and P. vivax, showing high potency, a broad stage specificity of action, including gametocyte stages (25), and synergism with other antimalarials (19, 21, 44). Although researchers and drug developers have been aware of the antimalarial properties of MB against P. falciparum for almost a century, it has never been widely used in clinical practice, largely due to its poor tolerability profile. Its side effects include headaches, nausea, and discoloration of urine and sclera, all of which are reversible. Neurotoxicity and mutagenicity have also been observed in animal models (45). However, recent clinical studies have demonstrated MB's ability to elicit an adequate cure for P. falciparum infection with acceptable tolerability in young children (46, 47), and MB plasma levels have been shown to be safe at concentrations 10-fold higher than the IC50s observed in our ex vivo experiments (48). In areas where artemisinin resistance is emerging, the partner drugs in combination therapies are under increasing pressure for the selection of resistance and the therapeutic agents available are limited. In this context, the utility of MB in the treatment of multidrug-resistant malaria warrants further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Lembaga Pengembangan Masyarakat Amungme Kamoro and the staffs of the Rumah Sakit Mitra Masyarakat (RSMM) Hospital and the Malaria Research Facility of the Papuan Health and Community Development Foundation (PHCDF) in Timika (Papua, Indonesia) for their support in conducting this study. We thank the Australian Red Cross blood transfusion service for the supply of human sera.

The study was funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Clinical Science (091625; R.N.P.), a National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant (1023438; R.N.P. and J.J.M.), a National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (1037304; R.N.P.), a Swiss National Science Foundation Fellowship for Advanced Researchers (J.M.), and the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV).

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2010. Global report on antimalarial drug efficacy and drug resistance: 2000-2010. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price RN, von Seidlein L, Valecha N, Nosten F, Baird JK, White NJ. 2014. Global extent of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 14:982–991. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70855-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. 2010. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria, 2nd ed World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, Ringwald P, Silamut K, Imwong M, Chotivanich K, Lim P, Herdman T, An SS, Yeung S, Singhasivanon P, Day NP, Lindegardh N, Socheat D, White NJ. 2009. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med 361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM. 2008. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med 359:2619–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lon C, Manning JE, Vanachayangkul P, So M, Sea D, Se Y, Gosi P, Lanteri C, Chaorattanakawee S, Sriwichai S, Chann S, Kuntawunginn W, Buathong N, Nou S, Walsh DS, Tyner SD, Juliano JJ, Lin J, Spring M, Bethell D, Kaewkungwal J, Tang D, Chuor CM, Satharath P, Saunders D. 2014. Efficacy of two versus three-day regimens of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for uncomplicated malaria in military personnel in northern Cambodia: an open-label randomized trial. PLoS One 9:e93138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders DL, Vanachayangkul P, Lon C, U.S. Army Military Malaria Research Program, National Center for Parasitology, Entomology, and Malaria Control (CNM), Royal Cambodian Armed Forces. 2014. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure in Cambodia. N Engl J Med 371:484–485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1403007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Bei ZC, Wang JY, Cao WC. 2011. Plasmodium berghei K173: selection of resistance to naphthoquine in a mouse model. Exp Parasitol 127:436–439. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Gao B, Huang K. 1999. Comparison of sensitivity of artesunate-sensitive and artesunate-resistant Plasmodium falciparum to chloroquine and amodiaquine. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 17:353–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H, Yang C, Li C, Li X, Li L, Yang C. 2004. Curative effect on artesunate-naphthoquine combination in treatment of malaria. Chin J Parasitic Dis Control 2004-2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toure OA, Penali LK, Yapi J-D, Ako BA, Toure W, Djerea K, Gomez GO, Makaila O. 2009. A comparative, randomized clinical trial of artemisinin/naphtoquine twice daily one day versus artemether/lumefantrine six doses regimen in children and adults with uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Cote d'Ivoire. Malar J 8:148. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hombhanje FW, Linge D, Saweri A, Kuanch C, Jones R, Toraso S, Geita J, Masta A, Kevau I, Hiawalyer G, Sapuri M. 2009. Artemisinin-naphthoquine combination (ARCO) therapy for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in adults of Papua New Guinea: a preliminary report on safety and efficacy. Malar J 8:196. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meremikwu MM, Odey F, Oringanje C, Oyo-Ita A, Effa E, Esu EB, Eyam E, Oduwole O, Asiegbu V, Alaribe A, Ezedinachi EN. 2012. Open-label trial of three dosage regimens of fixed-dose combination of artemisinin and naphthoquine for treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Calabar, Nigeria. Malar J 11:413. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laman M, Moore BR, Benjamin JM, Yadi G, Bona C, Warrel J, Kattenberg JH, Koleala T, Manning L, Kasian B, Robinson LJ, Sambale N, Lorry L, Karl S, Davis WA, Rosanas-Urgell A, Mueller I, Siba PM, Betuela I, Davis TM. 2014. Artemisinin-naphthoquine versus artemether-lumefantrine for uncomplicated malaria in Papua New Guinean children: an open-label randomized trial. PLoS Med 11:e1001773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Yang H-l, Xu J-W, Wang J-Z, Nie R-H, Li C-F. 2013. Artemisinin-naphthoquine combination versus chloroquine-primaquine to treat vivax malaria: an open-label randomized and noninferiority trial in Yunnan Province, China. Malar J 12:409. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tjitra E, Hasugian AR, Siswantoro H, Prasetyorini B, Ekowatiningsih R, Yusnita EA, Purnamasari T, Driyah S, Salwati E, Yuwarni E, Januar L, Labora J, Wijayanto B, Amansyah F, Dedang TA, Purnama A. 2012. Efficacy and safety of artemisinin-naphthoquine versus dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in adult patients with uncomplicated malaria: a multi-centre study in Indonesia. Malar J 11:153. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guttmann P, Ehrlich P. 1891. Ueber die Wirkung des Methylenblau bei Malaria. Berl Klin Wochenz 28:4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wainwright M, Crossley KB. 2002. Methylene blue—a therapeutic dye for all seasons? J Chemother 14:431–443. doi: 10.1179/joc.2002.14.5.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akoachere M, Buchholz K, Fischer E, Burhenne J, Haefeli WE, Schirmer RH, Becker K. 2005. In vitro assessment of methylene blue on chloroquine-sensitive and -resistant Plasmodium falciparum strains reveals synergistic action with artemisinins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:4592–4597. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4592-4597.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ademowo OG, Nneji CM, Adedapo AD. 2007. In vitro antimalarial activity of methylene blue against field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum from children in Southwest Nigeria. Indian J Med Res 126:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garavito G, Bertani S, Rincon J, Maurel S, Monje MC, Landau I, Valentin A, Deharo E. 2007. Blood schizontocidal activity of methylene blue in combination with antimalarials against Plasmodium falciparum. Parasite 14:135–140. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2007142135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okombo J, Kiara SM, Mwai L, Pole L, Ohuma E, Ochola LI, Nzila A. 2012. Baseline in vitro activities of the antimalarials pyronaridine and methylene blue against Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Kenya. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1105–1107. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05454-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vennerstrom JL, Makler MT, Angerhofer CK, Williams JA. 1995. Antimalarial dyes revisited: xanthenes, azines, oxazines, and thiazines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:2671–2677. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.12.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascual A, Henry M, Briolant S, Charras S, Baret E, Amalvict R, Huyghues des Etages E, Feraud EEM, Rogier C, Pradines B. 2011. In vitro activity of Proveblue (methylene blue) on Plasmodium falciparum strains resistant to standard antimalarial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2472–2474. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01466-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adjalley SH, Johnston GL, Li T, Eastman RT, Ekland EH, Eappen AG, Richman A, Sim BK, Lee MC, Hoffman SL, Fidock DA. 2011. Quantitative assessment of Plasmodium falciparum sexual development reveals potent transmission-blocking activity by methylene blue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:E1214–E1223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112037108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delves MJ, Ruecker A, Straschil U, Lelievre J, Marques S, Lopez-Barragan MJ, Herreros E, Sinden RE. 2013. Male and female Plasmodium falciparum mature gametocytes show different responses to antimalarial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3268–3274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00325-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coulibaly B, Zoungrana A, Mockenhaupt FP, Schirmer RH, Klose C, Mansmann U, Meissner PE, Müller O. 2009. Strong gametocytocidal effect of methylene blue-based combination therapy against falciparum malaria: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 4:e5318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandi G, Witte S, Meissner P, Coulibaly B, Mansmann U, Rengelshausen J, Schiek W, Jahn A, Sanon M, Wust K, Walter-Sack I, Mikus G, Burhenne J, Riedel KD, Schirmer H, Kouyate B, Müller O. 2005. Safety of the combination of chloroquine and methylene blue in healthy adult men with G6PD deficiency from rural Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health 10:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meissner PE, Mandi G, Witte S, Coulibaly B, Mansmann U, Rengelshausen J, Schiek W, Jahn A, Sanon M, Tapsoba T, Walter-Sack I, Mikus G, Burhenne J, Riedel KD, Schirmer H, Kouyate B, Müller O. 2005. Safety of the methylene blue plus chloroquine combination in the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in young children of Burkina Faso [ISRCTN27290841]. Malar J 4:45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suwanarusk R, Russell B, Ong A, Sriprawat K, Chu CS, PyaePhyo A, Malleret B, Nosten F, Renia L. 2014. Methylene blue inhibits the asexual development of vivax malaria parasites from a region of increasing chloroquine resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:124–129. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karyana M, Burdarm L, Yeung S, Kenangalem E, Wariker N, Maristela R, Umana KG, Vemuri R, Okoseray MJ, Penttinen PM, Ebsworth P, Sugiarto P, Anstey NM, Tjitra E, Price RN. 2008. Malaria morbidity in Papua Indonesia, an area with multidrug resistant Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J 7:148. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratcliff A, Siswantoro H, Kenangalem E, Wuwung M, Brockman A, Edstein MD, Laihad F, Ebsworth EP, Anstey NM, Tjitra E, Price RN. 2007. Therapeutic response of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in southern Papua, Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 101:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell B, Chalfein F, Prasetyorini B, Kenangalem E, Piera K, Suwanarusk R, Brockman A, Prayoga P, Sugiarto P, Cheng Q, Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Price RN. 2008. Determinants of in vitro drug susceptibility testing of Plasmodium vivax. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1040–1045. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01334-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lourens C, Watkins WM, Barnes KI, Sibley CH, Guerin PJ, White NJ, Lindegardh N. 2010. Implementation of a reference standard and proficiency testing programme by the World Wide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN). Malar J 9:375. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marfurt J, Chalfein F, Prayoga P, Wabiser F, Kenangalem E, Piera KA, Machunter B, Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Price RN. 2011. Ex vivo drug susceptibility of ferroquine against chloroquine-resistant isolates of Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4461–4464. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01375-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marfurt J, Chalfein F, Prayoga P, Wabiser F, Kenangalem E, Piera KA, Fairlie DP, Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Andrews KT, Price RN. 2011. Ex vivo activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:961–966. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01220-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharrock WW, Suwanarusk R, Lek-Uthai U, Edstein MD, Kosaisavee V, Travers T, Jaidee A, Sriprawat K, Price RN, Nosten F, Russell B. 2008. Plasmodium vivax trophozoites insensitive to chloroquine. Malar J 7:94. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong RP, Lautu D, Tavul L, Hackett SL, Siba P, Karunajeewa HA, Ilett KF, Mueller I, Davis TM. 2010. In vitro sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum to conventional and novel antimalarial drugs in Papua New Guinea. Trop Med Int Health 15:342–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schirmer RH, Coulibaly B, Stich A, Scheiwein M, Merkle H, Eubel J, Becker K, Becher H, Muller O, Zich T, Schiek W, Kouyate B. 2003. Methylene blue as an antimalarial agent. Redox Rep 8:272–275. doi: 10.1179/135100003225002899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pradines B, Hovette P, Fusai T, Atanda HL, Baret E, Cheval P, Mosnier J, Callec A, Cren J, Amalvict R, Gardair JP, Rogier C. 2006. Prevalence of in vitro resistance to eleven standard or new antimalarial drugs among Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Pointe-Noire, Republic of the Congo. J Clin Microbiol 44:2404–2408. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00623-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ignatushchenko MV, Winter RW, Bachinger HP, Hinrichs DJ, Riscoe MK. 1997. Xanthones as antimalarial agents; studies of a possible mode of action. FEBS Lett 409:67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Färber PM, Arscott LD, Williams CH Jr, Becker K, Schirmer RH. 1998. Recombinant Plasmodium falciparum glutathione reductase is inhibited by the antimalarial dye methylene blue. FEBS Lett 422:311–314. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pastrana-Mena R, Dinglasan RR, Franke-Fayard B, Vega-Rodriguez J, Fuentes-Caraballo M, Baerga-Ortiz A, Coppens I, Jacobs-Lorena M, Janse CJ, Serrano AE. 2010. Glutathione reductase-null malaria parasites have normal blood stage growth but arrest during development in the mosquito. J Biol Chem 285:27045–27056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dormoi J, Pascual A, Briolant S, Amalvict R, Charras S, Baret E, Huyghues des Etages E, Feraud M, Pradines B. 2012. Proveblue (methylene blue) as an antimalarial agent: in vitro synergy with dihydroartemisinin and atorvastatin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3467–3469. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06073-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gillman PK. 2011. CNS toxicity involving methylene blue: the exemplar for understanding and predicting drug interactions that precipitate serotonin toxicity. J Psychopharmacol 25:429–436. doi: 10.1177/0269881109359098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zoungrana A, Coulibaly B, Sie A, Walter-Sack I, Mockenhaupt FP, Kouyate B, Schirmer RH, Klose C, Mansmann U, Meissner P, Müller O. 2008. Safety and efficacy of methylene blue combined with artesunate or amodiaquine for uncomplicated falciparum malaria: a randomized controlled trial from Burkina Faso. PLoS One 3:e1630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Müller O, Mockenhaupt FP, Marks B, Meissner P, Coulibaly B, Kuhnert R, Buchner H, Schirmer RH, Walter-Sack I, Sie A, Mansmann U. 2013. Haemolysis risk in methylene blue treatment of G6PD-sufficient and G6PD-deficient West-African children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria: a synopsis of four RCTs. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 22:376–385. doi: 10.1002/pds.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walter-Sack I, Rengelshausen J, Oberwittler H, Burhenne J, Mueller O, Meissner P, Mikus G. 2009. High absolute bioavailability of methylene blue given as an aqueous oral formulation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 65:179–189. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]