Abstract

Benznidazole is considered the first-line treatment option against Chagas disease. The major drawback of benznidazole is its toxicity profile. The main objectives of this study were to describe the adverse events (AEs) in patients with chronic Chagas disease treated with benznidazole, determine the risk factors involved and compare the toxic profiles of two different preparations of the drug from ELEA and Roche. A total of 746 patients were diagnosed with Chagas disease in a 5-year period, and of these 472 were treated with benznidazole. A high proportion of patients (n = 360 [76%]) suffered AEs, the most frequent being those related to hypersensitivity (52.9% of patients), headache (12.5%), and epigastric pain (10.4%). In 72 (12.7%) cases, treatment was discontinued. Overall, women had a higher incidence of AEs compared to men (81.3% versus 66%, P = 0.001) and were subject to higher levels of hypersensitivity-related events. Dermatological events, digestive tract manifestations, and general symptoms had a greater likelihood to appear around day 10 and neurological AEs around day 40 after starting treatment. With respect to liver function and hematological tests, the majority of patients did not suffer significant perturbation of liver enzymes or altered blood cell counts. However, 14 patients suffered from neutropenia, and 14 patients had aminotransferase levels that were more than four times the upper limit of the normal range. Patients treated with the ELEA benznidazole product experienced more arthromyalgia, neutropenia, and neurological disorders (mainly paresthesias) than those treated with the Roche product. Both drug products resulted in approximately the same percentage of permanent withdrawals.

INTRODUCTION

Chagas disease, one of the considered neglected tropical diseases, remains a public health problem in Latin America, and a new challenge in countries where the disease is not endemic. Its causative agent, Trypanosoma cruzi, was first discovered by Carlos Chagas in 1909 (1). Prevention strategies, access to accurate diagnosis, and an affordable treatment are the main actions that can be offered to patients.

The current therapeutic scenario is limited to nifurtimox, derived from nitrofuran, and benznidazole, a nitroimidazole derivate. Nifurtimox was launched by Bayer in 1965 and benznidazole was launched by Roche in 1971 (2). Unfortunately, therefore, over the last 50 years the treatment of Chagas disease has remained unaltered. These two drugs have been shown to be curative in the acute phase of the disease, with parasitological cure rates ranging from 60 to 85% rising to 100% in congenitally transmitted cases. However, in the chronic phase of the disease, cure rates of only 15 to 40% are achieved (3). The major drawback of both drugs is their toxicity profile. The severity of the adverse events (AEs) leads to permanent withdrawal of treatment in 6 to 40% of patients receiving nifurtimox and 7 to 30% of those receiving benznidazole (3, 4). Despite limited cure rates for both compounds, during the chronic phase, due to its availability and better tolerance compared to nifurtimox, benznidazole is considered the first-line treatment option against Chagas disease regardless of clinical phase (5).

Benznidazole provokes a broad spectrum of adverse effects. The most common are those related to hypersensitivity, such as dermatitis, which occurs in 29 to 50% of patients, while digestive tract intolerance appears in 5 to 15% of patients. General symptoms such as anorexia, asthenia, headache, and sleeping disorders are present in up to 40% of patients. Neuropathy is present in almost one-third of the patients, but this only represents a relevant clinical problem in a small percentage of patients (6). Depression of bone marrow is another important side effect that can be manifested as neutropenia, agranulocytosis, or thrombocytopenia (6). Although this AE is considered rare (reported among fewer than 1% of patients), its very nature makes it one of the most serious.

Benznidazole was developed and then commercialized over a long period by Roche. In 2003, the license and technology were transferred to LAFEPE (Laboratório do Estado de Pernambuco), making this Brazilian state pharmaceutical laboratory the sole producer of benznidazole. Initially LAFEPE produced batches of the final product with the active ingredient donated by Roche. However, in 2010 due to a series of logistic problems, the production and distribution of benznidazole were withdrawn, leading to a worldwide shortage of the drug. Not until early 2012, did a new manufacturer, ELEA, a private pharmaceutical company based in Argentina, announce that it had produced and registered generic benznidazole.

The main objectives of the present study were to describe the adverse events found in our large cohort of chronic Chagas disease patients treated with benznidazole, to determine the risk factors involved, and to compare the toxic profiles of the two different commercial preparations of the drug.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective observational study was performed in the Infectious Diseases Department of the University Hospital Vall d'Hebron, a tertiary hospital, included in The International Health Program of Catalonian Health Institute, PROSICS Barcelona, Spain.

Study population and data collection.

All patients presenting with Chagas disease who attended PROSICS Barcelona from June 2008 to June 2013 and were treated with benznidazole are included in the present study. The following clinical and epidemiological data were collected: age, gender, country of origin, time since arrival in Spain, clinical symptoms, comorbidities, visceral involvement study, and completion of treatment. Cardiac involvement was assessed through a physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram, and chest X-ray. For the gastrointestinal involvement assessment, physical examination, esophagogram, and barium enema were undertaken; radiological evaluation was performed on all patients independent of their symptoms. Eosinophilia was defined as an eosinophil cell count of ≥500 cells/μl and/or a percentage of ≥7%. Neutropenia was considered present when the absolute neutrophil count was under 1,000 cell/μl. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the hospital and verbal informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Diagnosis of Chagas disease.

Diagnosis of Chagas disease was confirmed by two seropositive results from three different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs): Bioelisa Chagas (Biok, Spain), Ortho T. cruzi ELISA (Jonhson & Johnson, USA) or ELISA cruzi (bioMérieux, France). When serological tests were discordant, sera were tested by an in-house Western blot method using a lysate from T. cruzi epimastigotes to confirm the diagnosis (7).

Treatment protocol.

Treatment with benznidazole was offered to all patients diagnosed with Chagas disease who were less than 50 years old. Benznidazole at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day (maximum, 300 mg/day), divided into three doses, was administered for 60 days. Patients were assessed at the baseline and on days 15, 30, and 60. A structured patient interview focused on AEs, and hematological and biochemical analyses were performed at each visit. According to the severity of AEs, the responsible physician determined whether to stop therapy permanently or interrupt temporarily the drug's administration. In both situations, concomitant treatment was administered to the patients (corticosteroids or antihistamines). In cases of moderate adverse reactions, the drug was reintroduced using a stepwise increasing dose regimen (starting from 12.5 mg/24 h) when the previous AE symptomology had disappeared. Patients were informed to feel free to come to the hospital whenever they have any AE. The choice of manufacturer was based on commercial availability. Patients diagnosed before 2012 were treated with Lafepe-Roche's benznidazole, and those diagnosed beyond 2012 were treated with ELEA's benznidazole.

Statistical analysis.

Continuous variables were compared to the Mann-Whitney U test and expressed as the medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables were compared to the chi-squared test or Fisher test when the expected frequency was ≤5 and presented as absolute numbers and proportions. A linear mixed-effects model for repeated measures was used to compare white blood cells and liver enzymes values over time. Univariate analyses were performed, and only those variables which were statistically significant were included in the logistic model. A stepwise regression with forward selection of variables was used. Separate logistic models for each outcome were constructed. SPSS software for Windows (verson 15.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

A total of 746 patients were diagnosed with Chagas disease in the 5-year period of the present study. Of these patients, 472 were treated with benznidazole. The major cause for not treating the patients was the loss to follow-up (201 patients, 73.3%), mainly during the shortage period of benznidazole, so we did not even have the opportunity to offer them the treatment. Fifty-three patients (19.3%) were recently diagnosed, and treatment had not yet been initiated. Twenty patients (7.3%) were not treated because they were more than 50 years old (the age limit according to international recommendations for treatment). Among treated patients, 322 (68.2%) were women, most were originally from Bolivia (92%), and they had a median age of 37 years (range, 31 to 44 years). No differences were found regarding the baseline characteristics of the patients according the treatment used (Table 1). Fifty-five (11.6%) patients were considered to have chagasic myocardiopathy, 80 (18%) had digestive tract involvement, and in 21 (4.4%) cases there was a mixed form (both cardiac and digestive forms).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics according to benznidazole manufacturer

| Characteristic | Benznidazole manufacturer |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roche (n = 264) | ELEA (n = 208) | ||

| Mean patient age in yr (IQR) | 36 (31–44) | 37 (32–45) | >0.05 |

| No. (%) female | 139 (52) | 111 (53) | >0.05 |

| No. (%) of patients with clinical involvement | >0.05 | ||

| Digestive form | 50 (18.9) | 30 (14.4) | |

| Cardiac forma | 38 (14.4) | 17 (8.2) | |

| Kuschnir 1 | 35 (13.2) | 15 (7.2) | |

| Kuschnir 2 | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Median baseline laboratory values (IQR) | >0.05 | ||

| Leukocytes (cells/μl) | 6,050 (5,175–7,200) | 6,100 (5,400–7,375) | |

| Neutrophils (cells/μl) | 3,400 (2,800–4,200) | 3,400 (2,700–4,300) | |

| Eosinophils (cells/μl) | 100 (100–300) | 200 (100–375) | |

| Platelets (cells [10–E9]/liter) | 244 (205–285) | 243 (212–275) | |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/liter) | 21 (18–27) | 22 (19–28) | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/liter) | 19 (14–27) | 19 (14–29) | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/liter) | 78 (63–93) | 83 (71–105) | |

| Gamma glutamyltransferase (IU/liter) | 20 (816–30) | 20 (16–35) | |

The Kuschnir scale measures clinical cardiac involvement in Chagas disease. A score of 0 indicates reactive serum and a normal electrocardiogram and chest radiograph; a score of 1 indicates reactive serum, an abnormal electrocardiogram, and a normal chest radiograph; a score of 2 indicates reactive serum, a chest radiograph showing cardiac enlargement, and no radiologic or clinical signs of heart failure; a score of 3 indicates heart failure.

A high proportion of patients (360 patients, 76%) had one or more AEs. Hypersensitivity phenomena (250 patients, 53%) with a dermatological involvement in all patients but one were the most frequents followed by headache (59 patients, 12.5%) and epigastric pain (49 patients, 10.4%). For more details, see Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Description of adverse events during benznidazole treatment

| Adverse eventa | No. (%) of patients (n = 472) | Median time of appearance in days (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypersensitivity | 250 (52.9) | 12 (7–20) |

| Rash | 29 (6.1) | |

| Rash and pruritus | 148 (31.4) | |

| Pruritus | 72 (15.3) | |

| Desquamation | 5 (1.1) | |

| Fever | 8 (1.7) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 3 (0.6) | |

| Angioedema | 5 (1.1) | |

| Digestive | 91 (19.3) | 10 (5–25) |

| Epigastralgia | 49 (10.4) | |

| Nausea and vomit | 21 (4.5) | |

| General symptoms | 131 (27.7) | 10 (5–24) |

| Somnolence | 46 (9.7) | |

| Headache | 59 (12.5) | |

| Alopecia | 4 (0.8) | |

| Arthromyalgia | 19 (4) | |

| Asthenia | 15 (3.2) | |

| Mucosa dryness | 2 (0.4) | |

| Neurological | 33 (7) | 40 (20–50) |

| Dysgeusia | 9 (1.9) | |

| Paresthesia | 24 (5) | |

| Analytical disorder | 72 (15.4) | 30 (15–50) |

| Neutropenia | 14 (4.2) | |

| Hypertransaminasemia | 58 (12.3) | |

| Increase in alanine aminotransferase | ||

| >2 to 3 ULN | 13 (2.7) | |

| >3 to 4 ULN | 4 (0.8) | |

| >4 ULN | 6 (1) | |

| Increase in aspartate aminotransferase | ||

| 2 to 3 ULN | 29 (6.1) | |

| >3 to 4 ULN | 15 (3.2) | |

| >4 ULN | 14 (2.9) |

ULN, upper limit of normal.

As a consequence of the AEs, treatment was temporarily interrupted in 31 (6.5%) patients, while in 72 (12.7%) cases benznidazole was permanently withdrawn. The major reason for discontinuing treatment was dermatitis in 44 (74%) patients. Four of these individuals fulfilled clinical and analytical criteria of DRESS syndrome (i.e., drug reaction [or rash] with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms). There were not any association between the clinical involvement and the incidence of any AE.

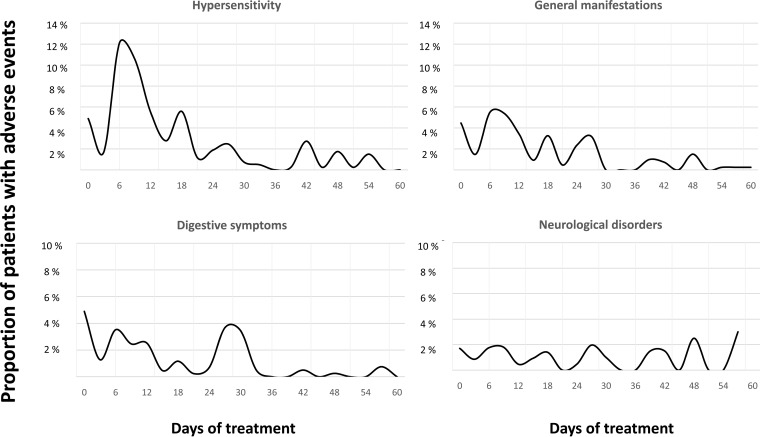

Women had an overall higher incidence of AEs compared to male patients (261 of 322 [81.3%] versus 99 of 150 [66%], respectively; P = 0.001), specifically digestive tract disturbances (77 of 322 [23.9%] versus 19 of 150 [12.7%]; P = 0.004) and also general symptoms (102 of 322 [31.7%] versus 30 of 150 [20%]; P = 0.008). Women also had a higher proportion suffering hypersensitivity-related events, but this did not reach statistical significance (175 of 322 [65.1%] versus 69 of 150 [46.3%]; P = 0.058). No differences were observed between the sexes in the numbers discontinuing benznidazole therapy as a result of AEs (females at 49 of 322 [15%] versus males at 24 of 150 [16%]). Details are given in Table 3. With respect to age, patients with neurological disorders were found to be older (42 years old [range, 36 to 48] versus 37 years old [range, 31 to 44], P = 001). No association was found between eosinophilia and other AEs, notably hypersensitivity. All AEs could appear at any time during the treatment period, but dermatological events, digestive tract manifestations, and general symptoms had a greater likelihood of occurring around day 10 and neurological AEs around day 40 (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Risk factors for adverse events during the benznidazole treatment perioda

| Category | Benznidazole manufacturer |

Gender |

Eosinophilia |

Age |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) |

P values |

No. (%) |

P values |

No. (%) |

P values |

Comparisonc |

P values |

||||||||

| Roche (n = 264) | ELEA (n = 208) | P | P* | Female (n = 322) | Male (n = 150) | P | P* | Yes (n = 127) | No (n = 345) | P | P* | P | P* | ||

| Overall AEs | 194 (73) | 166 (79) | 0.12 | 261 (81) | 99 (66.4) | 0.001 | 103 (81) | 259 (74.6) | 0.1 | 37 vs 37 | 0.9 | ||||

| Hypersensitivity | 139 (52) | 111 (53) | 0.92 | 175 (65.1) | 69 (46.3) | 0.058 | 76 (60.3) | 174 (50) | 0.06 | 37 vs 37 | 0.9 | ||||

| Digestive tract | 51 (19.3) | 40 (19.2) | 0.98 | 77 (23.9) | 19 (12.7) | 0.005 | 29 (23) | 67 (19.4) | 0.2 | 37 vs 37 | 0.6 | ||||

| General symptoms | 64 (24.2) | 67 (32.2) | 0.05 | 0.036 (1–2.3) | 102 (32) | 30 (20) | 0.008 | 0.009 (1.1–2.9) | 26 (20.6) | 106 (30.6) | 0.03 | 0.057 (0.4–1) | 37 vs 37 | 0.3 | |

| Arthromyalgia | 5 (1.9) | 14 (7.2) | 0.009 | 0.016 (1.3–10) | 13 (4) | 6 (4) | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 18 (5.2) | 0.03 | 0.069 (0.02–11.6) | 37 vs 37 | 0.5 | ||

| Neurological disorders | 11 (4.16) | 21 (10)b | 0.01 | <0.001 (2.2–9.6) | 22 (7) | 10 (6.7) | 0.6 | 9 (7.1) | 23 (6.6) | 0.3 | 42 vs 37 | 0.01 | 0.019 (1–1.1) | ||

| Dysgeusia | 3 (0.6) | 6 (1.2) | 0.19 | 8 (2.5) | 1 (0.7) | 0.2 | 2 (1.5) | 7 (2) | 0.7 | 41 vs 37 | 0.9 | ||||

| Paresthesia | 8 (1.7) | 16 (3.9) | 0.03 | 15 (4.8) | 9 (6) | 0.6 | 6 (4.7) | 18 (5.1) | 0.7 | 43 vs 37 | 0.1 | ||||

| Analytical disorder | 39 (14.4) | 33 (15.8) | 0.5 | 48 (14.9) | 24 (16) | 0.7 | 24 (19) | 48 (14) | 0.2 | 38 vs 37 | 0.7 | ||||

| Neutropenia | 4 (1.5) | 10 (4.8) | 0.053 | 9 (2.8) | 5 (3.3) | 1 | 3 (2.4) | 9 (2.6) | 1 | 45 vs 37 | 0.09 | ||||

| Hypertransaminasemia | 35 (11.3) | 23 (11.7) | 0.4 | 39 (12.1) | 19 (12.7) | 1 | 21 (16.5) | 40 (11.5) | 0.7 | 37 vs 37 | 0.5 | ||||

| Treatment withdrawal | 44 (16.7) | 28 (13.5) | 0.3 | 49 (15.1) | 24 (16) | 0.8 | 21 (16.5) | 52 (14.9) | 0.6 | 37 vs 37 | 0.3 | ||||

Data are reported as the number (%) of patients or the median P value (confidence interval). In addition to standard P value calculations, data in the P* column were determined by multivariate logistic regression analysis. These results are expressed as P values and their respective 95% confidence intervals. Boldfacing is used to indicate statistical significance.

Note that one patient suffered from both neurological adverse events (AEs).

These numbers correspond to the median age of the patients suffering from the stated AE versus the age of those not having the adverse event.

FIG 1.

Time to appearance of the major AEs during the benznidazole treatment period.

Clinical laboratory tests revealed that most patients did not suffer from marked changes in liver enzymes and blood cell count (leukocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets). On day 30, there was a significant increase in transaminase titers and a significant decrease in white blood cells counts (P < 0.001). Despite this decline in leukocytes, they remained within the normal range. After treatment was terminated in these patients, all parameters returned to normal (Fig. 2). Fourteen patients suffered from neutropenia (neutrophils under 1,000 cells/μl) with a median of 425 cells/μl (range, 300 to 600 cells/μl), and another 14 patients had aminotransferase levels that were more than four times the upper limit of the normal range. In addition, five patients discontinued therapy because of their neutrophil levels, and one patient discontinued therapy due to severe hepatotoxicity.

FIG 2.

Monitoring of white blood cells and liver enzymes during the benznidazole treatment period. Leuk, leukocytes; Neut, neutrophils; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase. P values are in reference of the differences of white blood cells or liver enzymes values compared to their respective baseline values. *, Statistically significant differences were only found on day 30 after the start of treatment.

The change of benznidazole manufacturer was not associated with a higher overall incidence of AEs. Nonetheless, those patients treated with ELEA's benznidazole experienced more general symptoms (mainly arthromyalgia), more neutropenia, and more neurological disorders, mainly paresthesia. Both drug products had a similar percentage of withdrawals. Details are given in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Despite the modest cure rates, benznidazole remains the best treatment option against Chagas disease. Given the current scenario of limited therapeutic options, we will continue using benznidazole for the disease's treatment for the time being (3). The high incidence of AEs represents the most important disadvantage of the drug's use, constraining its efficacy, by provoking permanent interruption in therapy in ca. 15% of patients (8).

Despite the important constraints that benznidazole's toxic profile represents for its clinical use, the mechanisms leading to its toxicity and even the drug's mechanism of action are still not fully understood. The enzymatic reduction of its nitro group results in the production of several metabolites. The direct interaction of these metabolites with significant cellular constituents, their accumulation, the allergic response they elicit, or even a combination of all of these factors could be the reason for the compound's toxicity (8–11).

The published incidence of AEs varies from 40 to 50% up to 98% of patients (4, 6, 8, 12–17). The data from our study are in the middle of the published ranges (76%). Apart from the high variability, probably due to subjectivity in both answering the questions and interpreting patient responses, what all studies have in common is a high incidence of side effects linked to benznidazole treatment.

The most common AE observed in our study was hypersensitivity, with a high proportion of cutaneous toxicity (249 of 250 patients [99.6%]), as is the case in the vast majority of the above-mentioned studies. Although mechanistically its toxic pathway has not yet been studied, it is suspected to be an allergic phenomenon and probably IgE mediated. More than 50% of our patients suffered from hypersensitivity, and it was also the leading cause of treatment interruption. Four patients, also fulfilled criteria for DRESS syndrome, although a skin biopsy was only performed in two of these individuals. This serious AE appeared between days 10 and 14 of treatment.

General symptoms range widely from one study to another, due to the difficulty in assessing them accurately, something which makes cross-study comparisons difficult. In addition, laboratory parameters, although certainly more objective, are not always monitored or reported in many studies. In the case of liver enzymes in our study, we have observed a significant increase in alanine and aspartate aminotransferase titers on day 30 of treatment. Although the proportion of patients suffering moderate to severe increases in these liver enzymes is supposed to be low according to previous published papers (8), we had 29 patients who reached more than three times the upper limit of normality, which led in one case to a permanent halt in treatment.

Regarding the hematological parameters, neutropenia is considered one of the most serious AEs, but, fortunately, it is extremely rare. Over the monitoring period, we also witnessed a significant decrease in neutrophils by day 30 of treatment. In most cases, the white blood cell count did not fall significantly, but 14 (4.2%) patients had levels under 1,000 neutrophils/μl. Only one individual was admitted to hospital, but this individual made a complete recovery and was later discharged. The higher rate of either neutropenia or hypertransaminasemia observed in our study might be explained by improved close monitoring of patients as has happened in other studies (15).

There are some AEs which have a certain temporal pattern. Dermatological manifestations and digestive symptomatology tend to appear around day 10 of treatment, whereas neurological disorders tend to appear after day 40 of treatment. The pattern of appearance of symptoms has been attributed to the toxicity mechanism inherent to each AE. In the case of cutaneous toxicity, the allergic hypothesis might provide some insights into its early appearance. Neurological disorders have been related to the cumulative total dose; therefore, the presence of polyneuritis or dysgeusia might be directly proportional to the time needed to reach a toxic threshold (estimated to be 18 g) (8, 10).

Among the risk factors associated with overall AEs, one increased risk factor appears to be gender. Limited studies have been undertaken to study this, but where evaluated, the data point to an increased risk of developing toxicity, in women (4, 12). In our study, there was a higher overall incidence of AEs in female compared to male patients, mainly due to side effects categorized as general symptoms (headache, astenia, drowsiness, etc.). We also observed a trend in hypersensitivity-related events, but this was without statistical significance. Some authors have suggested that women have higher nitroreductive activity, and given that this is important in benznidazole metabolism, there could exist a physiopathological basis for the higher incidence of AEs in females (9).

Other classical risk factors are the age of the patient and the duration of the treatment. In our study, it was intended to treat all patients for 60 days; however, this goal could not be analyzed. Furthermore, age had an impact on the occurrence of neurological disorders, but we did not observe any correlation of age with other AEs or treatment compliance (the number of patient withdrawals), probably because of the narrow age range of the patients studied. In summary, despite the wide use of benznidazole and the high incidence of reported AEs, there still remains a lack of knowledge over the risk factors to be considered when the drug is used and the mechanism(s) surrounding its toxicity.

The disruption in the supply of benznidazole from LAFEPE was followed by the emergence of the new manufacturer ELEA. We observed that the benznidazole produced by ELEA (Abarax) was associated with more cases of neurological disorders (mainly neuropathy) and a greater incidence of neutropenia (almost reaching statistical significance) but, fortunately, without any clinical relevance. Both types of events have been attributed to a cumulative-drug mechanism. The data from comparative pharmacokinetics would be extremely valuable in order to better understand the differences observed between the ELEA and Roche products.

Beyond the extent and type of AEs, the number of withdrawals is what represents the greatest loss to the overall efficacy of benznidazole (17). We had to interrupt the treatment of almost 13% of our patients which is consistent with the average of previously reported studies (4, 6, 8, 12–17). Therefore, strategies focused on reducing AEs and consequently achieving better therapy completion rates are strongly recommended. The addition of antioxidant agents such as thioctic acid has previously failed to prevent AEs (18). Low-fat and hypoallergenic diets have also been proposed as a means to reduce AEs, but their benefits have not yet been evaluated (8). There is also controversy over the relationship between drug concentrations and AEs. Although some authors hypothesize that there could exist a direct correlation with drug exposure (4, 19), others have not found any association between serum drug concentration and adverse reactions (15). At this time, what seems the most effective strategy is to offer patients a close follow-up in order to monitor AEs and to then deal with these early. In accordance, with the time of first appearance of the overall AEs, it would appear that the most reasonable approach is to supervise patients closely during their first month of benznidazole therapy.

We note that benznidazole has a high incidence of undesirable side effects, most of which are treatable or reversible but which unfortunately lead to treatment interruption in a significant number of patients. Cutaneous manifestations are the most frequent AE and represent the major cause of treatment discontinuation. Women appear to be more susceptible to developing AEs, but this does not lead to increased discontinuation of treatment in female patients. The newer ELEA benznidazole product was associated with an increased risk of neurological disorders and general symptoms, mainly arthromyalgia. Close follow-up of patients during the duration of treatment is required, most notably during the first month and ideally with additional monitoring through blood tests whenever possible.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chagas C, Chagas C. 1909. Nova tripanozomiaze humana: estudos sobre a morfolojia e o ciclo evolutivo do Schizotrypanum cruzi n. gen., n. sp., ajente etiolojico de nova entidade morbida do homem. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1:159–218. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761909000200008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt BL, Rassi A Jr, Marin-Neto JA, Dantas RO, Maguire JH, Acquatella H, Morillo C, Kirchhoff LV, Gilman RH, Reyes PA, Salvatella R, Moore AC. 2007. Evaluation and treatment of Chagas disease in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA 298:2171–2181. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bern C. 2011. Antitrypanosomal therapy for chronic Chagas' disease. N Engl J Med 364:2527–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1014204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasslocher-Moreno AM, do Brasil PEAA, de Sousa AS, Xavier SS, Chambela MC, Sperandio da Silva GM. 2012. Safety of benznidazole use in the treatment of chronic Chagas' disease. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1261–1266. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. 2010. Chagas disease. Lancet 375:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinazo M-J, Muñoz J, Posada E, López-Chejade P, Gállego M, Ayala E, del Cacho E, Soy D, Gascon J. 2010. Tolerance of benznidazole in treatment of Chagas' disease in adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:4896–4899. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00537-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riera C, Verges M, Iniesta L, Fisa R, Gállego M, Tebar S, Portús M. 2012. Identification of a Western blot pattern for the specific diagnosis of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in human sera. Am J Trop Med Hyg 86:412–416. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Alvarez MG, Petti M, Bertocchi G, Armenti A. 2009. Side effects of benznidazole as treatment in chronic Chagas disease: fears and realities. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 7:157–163. doi: 10.1586/14787210.7.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castro JA, de Mecca MM, Bartel LC. 2006. Toxic side effects of drugs used to treat Chagas' disease (American trypanosomiasis). Hum Exp Toxicol 25:471–479. doi: 10.1191/0960327106het653oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancado JR. 2002. Long term evaluation of etiological treatment of Chagas disease with benznidazole. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo 44:29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maya JD, Cassels BK, Iturriaga-Vásquez P, Ferreira J, Faúndez M, Galanti N, Ferreira A, Morello A. 2007. Mode of action of natural and synthetic drugs against Trypanosoma cruzi and their interaction with the mammalian host. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 146:601–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tornheim JA, Lozano Beltran DF, Gilman RH, Castellon M, Solano Mercado MA, Sullca W, Torrico F, Bern C. 2013. Improved completion rates and characterization of drug reactions with an intensive Chagas disease treatment program in rural Bolivia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7:e2407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Pontes VMO, de Souza Júnior AS, daCruz FMT, Coelho HLL, Dias ATN, Coêlho ICB, de Oliveira MF. 2010. Adverse reactions in Chagas disease patients treated with benznidazole, in the State of Ceará. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 43:182–187. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822010000200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrilero B, Murcia L, Martínez-Lage L, Segovia M. 2011. Side effects of benznidazole treatment in a cohort of patients with Chagas disease in non-endemic country. Rev Esp Quimioter Publ Soc Esp Quimioter 24:123–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinazo M-J, Guerrero L, Posada E, Rodríguez E, Soy D, Gascon J. 2013. Benznidazole-related adverse drug reactions and their relationship to serum drug concentrations in patients with chronic Chagas disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:390–395. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01401-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fabbro DL, Streiger ML, Arias ED, Bizai ML, del Barco M, Amicone NA. 2007. Trypanocide treatment among adults with chronic Chagas disease living in Santa Fe city (Argentina), over a mean follow-up of 21 years: parasitological, serological and clinical evolution. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 40:1–10. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822007000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina I, Gómez i Prat J, Salvador F, Treviño B, Sulleiro E, Serre N, Pou D, Roure S, Cabezos J, Valerio L, Blanco-Grau A, Sánchez-Montalvá A, Vidal X, Pahissa A. 2014. Randomized trial of posaconazole and benznidazole for chronic Chagas' disease. N Engl J Med 370:1899–1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sosa-Estani S, Armenti A, Araujo G, Viotti R, Lococo B, Ruiz Vera B, Vigliano C, de Rissio AM, Segura EL. 2004. Treatment of Chagas disease with benznidazole and thioctic acid. Medicina 64:1–6. (In Spanish.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altcheh J, Moscatelli G, Mastrantonio G, Moroni S, Giglio N, Marson ME, Ballering G, Bisio M, Koren G, García-Bournissen F. 2014. Population pharmacokinetic study of benznidazole in pediatric Chagas disease suggests efficacy despite lower plasma concentrations than in adults. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e2907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]