Abstract

Determining the three-dimensional structure of myoglobin, the first solved structure of a protein, fundamentally changed the way protein function was understood. Even more revolutionary was the information that came afterward: protein dynamics play a critical role in biological functions. Therefore, understanding conformational dynamics is crucial to obtaining a more complete picture of protein evolution. We recently analyzed the evolution of different protein families including green fluorescent proteins (GFPs), β-lactamase inhibitors, and nuclear receptors, and we observed that the alteration of conformational dynamics through allosteric regulation leads to functional changes. Moreover, proteome-wide conformational dynamics analysis of more than 100 human proteins showed that mutations occurring at rigid residue positions are more susceptible to disease than flexible residue positions. These studies suggest that disease-associated mutations may impair dynamic allosteric regulations, leading to loss of function. Thus, in this study, we analyzed the conformational dynamics of the wild-type light chain subunit of human ferritin protein along with the neutral and disease forms. We first performed replica exchange molecular dynamics simulations of wild-type and mutants to obtain equilibrated dynamics and then used perturbation response scanning (PRS), where we introduced a random Brownian kick to a position and computed the fluctuation response of the chain using linear response theory. Using this approach, we computed the dynamic flexibility index (DFI) for each position in the chain for the wild-type and the mutants. DFI quantifies the resilience of a position to a perturbation and provides a flexibility/rigidity measurement for a given position in the chain. The DFI analysis reveals that neutral variants and the wild-type exhibit similar flexibility profiles in which experimentally determined functionally critical sites act as hinges in controlling the overall motion. However, disease mutations alter the conformational dynamic profile, making hinges more loose (i.e., softening the hinges), thus impairing the allosterically regulated dynamics.

Introduction

Proteins are the remarkable workhorses of life. In addition to being proficient, specific, and diverse, proteins have the paramount ability to evolve new functions. The ability to evolve and adapt is remarkable considering all modern proteins are thought to have diverged from a limited set of ancestral proteins. Recent evolutionary events such as the emergence of drug resistance and enzymes with the ability to degrade antibiotics underscore the need to understand the driving forces and mechanisms behind protein evolution.

In 1963, L. Pauling and E. Zuckerland stated it would be possible one day to infer the gene sequences of ancestral species to “synthesize these presumed components of extinct organisms and study the physiochemical properties of these molecules.” A half century later their prescient vision has been realized through advances in computational power, phylogenetics, and DNA synthesis. It is now possible to obtain ancestral sequences and resurrect ancient gene sequences in the laboratory. The first crucial step is to generate accurate phylogenetic trees by methods such as parsimony (1,2), maximum likelihood (1,3–6), and Markov Chain Monte Carlo-based Bayesian inference (7). These studies have shown that, as function evolves, a protein’s structure is more conserved than its sequence indicating that conformational dynamics must play an integral role in protein evolution.

Proteins are not static. A protein folded in its native state in vivo has internal dynamics where some parts are more flexible than others due to the interresidue network of interactions. Protein dynamics is critical to biological function—allosteric signaling, protein transport (8–12), ligand recognition (13), electron transfer (14), enzymatic reaction efficiency (15,16), and evolution of novel functions (17). Furthermore, evolutionary sequence variability has been analyzed in the context of protein structure dynamics (18–23) and shows a high correlation between evolutionary rates and the flexibility of individual positions (10,24).

Point mutations, either one or a few changes in the amino acid sequence, can alter the flexibility of a protein, causing a change in dynamics and, ultimately, the function. There is a growing body of evidence to support the idea that biological mechanisms can be explained by analyzing the contribution of individual residues to the conformational dynamics and stability of a protein (10,25–28).

The change of conformational dynamics as function evolves has recently been studied in three ancestral steroid receptors, the ancestors of mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs), and glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) (29). MRs and GRs arose by duplication of a single ancestor (AncCR) deep in the vertebrate lineage and then diverged in function. Through structural comparison of human MR and GR, two point mutations (S106P and L111Q) emerged to be critical in ligand specificity. However, swapping these residues between human MR and human GR yielded receptors with no binding activity (30). By resurrecting key ancestral proteins—AncCR, AncGR1, AncGR2—in MR and GR and determining their crystal structures, Thornton and colleagues were able to shed insight into how function diverges through time using both functional on-site and structural off-site permissive mutations (31–33). AncCR and AncGR1 have a promiscuous binding affinity, AncGR2 exclusively binds to cortisol. AncGR1 and AncGR2, which diverge functionally through 36 mutations, have highly similar experimental structures. However, a comparison of the conformational dynamics of the three ancestral proteins reveals AncCR and AncGR1 have a flexible binding pocket, suggesting flexibility plays a role in promiscuous binding affinity. In contrast, the mutations of AncGR2 lead to a rigid binding pocket, suggesting that as the binding pocket becomes cortisol specific, evolution acts to shape the binding pocket toward a specific ligand. Critical mutations were identified by analyzing the change in dynamics at each residue position using the mean square fluctuation profile and cross-correlation map.

Similar to the promiscuous ancestors of MRs and GRs, proteins corresponding to 2- to 3-billion-year-old Precambrian nodes in the evolution of Class A β-lactamases have been shown to be moderately efficient and promiscuous catalysts that are able to degrade a variety of antibiotics with catalytic efficiency levels similar to those of an average enzyme (34). Promiscuity is thought to play an essential role in the evolution of new functions as evinced by modern enzymes (34), which are highly efficient specialists and primordial enzymes, which were likely promiscuous generalists. Modern-day proteins can be thought of as evolved from generalists into specialists (35–40). Remarkably, there are only a few structural differences—in particular at the active-site regions—between the resurrected ancestral enzymes and penicillin-specialist modern β-lactamase. This then raises the question whether the functional differences arise from the conformational dynamics of the lactamases. The dynamics of the lactamases were simulated using replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD). Then the covariance matrix of C-alpha positions was calculated and analyzed using perturbation response scanning (PRS) (22,41). PRS relies on sequentially applying an external random force (i.e., a Brownian kick) on a single residue and quantifying the fluctuation response of other residues (10,41,42) using linear response theory. In a crowded cell environment, a protein can be exposed to many different types of forces exerted by the surrounding macromolecules and ligands. We mimic these forces, to a first approximation, by applying small random forces on the protein and computing the displacement of each residue through PRS (22,41). PRS results, thus, allow us to calculate a metric known as the dynamic flexibility index (DFI) that quantifies the resilience of each given residue to a perturbation occurring at another part of the chain (27) and quantifies the flexible and rigid parts of a protein. The special dynamics associated to substrate promiscuity of ancestral β-lactamases was revealed by patterns of high DFI values in regions close to the active site, illuminating the deformability required for the binding and catalysis of different ligands. These specific DFI patterns suggest that the protein’s native state is actually an ensemble of conformations displaying the structural variability in the active site region required for efficient binding of substrates of different sizes and shapes. On the other hand, DFI analysis of modern TEM-1 lactamase shows a comparatively rigid active-site region, likely reflecting adaptation for the efficient degradation of a specific substrate, penicillin (43). Principal component analysis of the ancestral β-lactamases and the extant TEM-1 lactamase reveal the special dynamics associated with substrate promiscuity and is in agreement with the functional divergence, as the highest-order modes of the ancient β-lactamases cluster together, separated from their modern descendant.

DFI analysis further reveals how functional evolution is related to changes in flexibility, specifically at hinge points, as the protein structure remains largely unchanged. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and PRS of reconstructed ancestral proteins of green fluorescent protein (GFP) shows the evolution of red color from a green ancestor emerged by migration of the hinge point from the active site diagonally across the beta-barrel fold (44). Although the flexibility of the mutational sites does not change in allosteric response to these mutants, both an increase in flexibility (softening) and decrease in flexibility (hardening) occurs for the regions of the beta fold that are widely separated.

Although the reconstruction of ancestral proteins provides insights about evolution, genome sequencing provides an opportunity to study protein evolution from a different perspective. With advancements in genome sequencing efforts, there has been an exponential growth in the number of known nonsynonymous single nucleotide variants (nSNVs). It is now clear that each personal genome contains millions of variants, many of which are nSNVs (45). More importantly, variations in the human exome, protein coding region, are already associated with more than a thousand diseases (46). Because disease-associated nSNVs coded in exomes are the part of the human genome best understood in how sequence relates to function via the known phenotypic impact, they represent our best chance to evaluate the role of conformational dynamics in genomics and evolution. In a recent study, the amino acid site-specific DFI metric was used to evaluate the effect of dynamic flexibility of individual positions on biological fitness and function in more than 100 proteins. The study found that disease-associated mutations occur predominately at low DFI sites (i.e., rigid hinge sites), indicating the importance of hinge sites. Neutral mutations, however, were more abundant at sites with high DFI, suggesting that flexible sites are more robust to mutations (27,28).

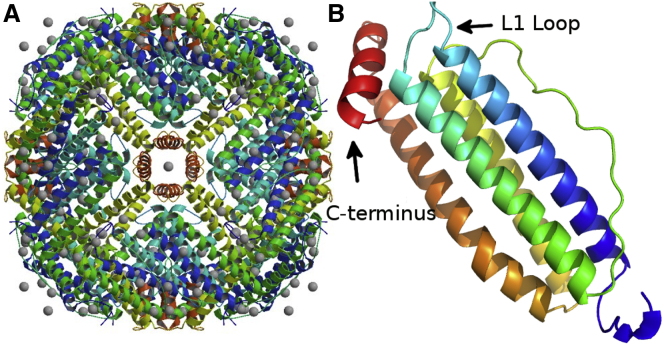

In this study, we investigated whether the conformational dynamics of a protein provides a mechanistic insight about why certain mutations lead to disease whereas others do not, even when both disease-associated and neutral mutations are close in sequence and result in a severe biochemical change upon mutation. Encouraged by the proteome-wide results of DFI, we analyzed whether DFI can provide further insight about disease mechanisms. We have studied the wild-type light chain subunit of human ferritin protein (FTL) and its mutant forms (Fig. 1). FTL contains 24 subunits and is able to store up to 4500 Fe (+3 oxidation state) atoms inside. Of these 24 subunits, some are of the heavy form, which catalyze the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ with oxygen, whereas the light form stores the oxidized iron and regulates the release of Fe3+ via a gating mechanism. The conformational dynamics of the light form subunit were sampled using REMD on the wild-type and mutant variants. DFI analysis was then performed to compare the change in conformational dynamics between the wild-type, neutral, and disease forms. As discussed in detail below, DFI analysis provides a unique picture of a protein as a machine controlled by rigid control knobs that transmit information to flexible regions via allosteric residue communication. Thus, allosteric residue communication between these rigid knobs and flexible portions is necessary for function. We found that a mutation that impairs (softens) these rigid knobs, leads to an overall loss in allosteric regulation and uncontrolled flabby dynamics.

Figure 1.

(A) Human ferritin contains 24 subunits and can store up to 4500 ferric (+3 oxidation state) atoms. Disruption in the function of ferritin has been linked to iron misregulation, anemia, cataract syndrome, basal ganglia disease, Hallervordern-Spatz Syndrome, Alzheimer's disease, and other neurodegenerative diseases. Of the 24 subunits, some are heavy form, which catalyze the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, whereas the light form stores the oxidized form (PDB ID: 3AJO). (B) The light subunit of the human ferritin protein colored from blue to red, where blue is the N terminus and red is the C terminus. The important regions for its function are the L1 loop (residues 40–50), critical for releasing Fe3+ and ion binding. The other critical regions for ion binding sites are residues 57–64, 84–92, and 118–135. (PDB ID: 2FG4). To see this figure in color, go online.

Materials and Methods

Human ferritin protein

The test set used for DFI analysis is the subunit of the FTL (PDB ID: 2FGL) and its mutant forms—L23M, D42Y, T93P, H124R, T30I, R40G, A96T, and H132P. The set of disease-associated mutations were found using the Human Genome Mutation Database (47). Human ferritin is involved in iron regulation; dysfunctions in the protein have been linked to disease-associated nSNV(s) manifested through anemia, cataract syndrome (48), basal ganglia disease (49,50), Parkinson’s disease (51), Huntington’s disease (52), Alzheimer’s disease, Hallverordern-Spatz syndrome (51–53), and an array of other neurodegenerative diseases. FTL was chosen for its integral role in human health and the experimental knowledge of disease-associated and neutral nSNVs.

REMD

The dynamics of the protein is sampled by running a REMD simulation. REMD samples the dynamics of a protein by performing multiple simulations at different temperatures (replicas) and allows the system to exchange configurations between replicas (54). By simultaneously simulating the protein at multiple temperatures, potential energy barriers that inhibit sampling can be overcome. The REMD simulations for the wild-type and mutants were simulated for 5 ns with convergence observed after 3 ns. The replicas are exponentially distributed between 240K and 450K to optimize the acceptance ratio for swapping structures (∼0.5). The Amber99SB force field (55) with generalized born surface area implicit solvent (56) is used to perform the simulation. The covariance matrix is extracted for the last half-nanosecond and used to calculate the DFI profile.

PRS Method and DFI Analysis

The canonical PRS method is originally based on the elastic network model (ENM), where the protein is viewed as an elastic network in which each node represents a residue (C-alpha atom) and a harmonic interaction is assigned to pairs of residues within a specified cutoff distance (22,41). In PRS, an external random force (i.e., a Brownian-like kick) is sequentially applied on each residue. The perturbation cascades through the residue interaction network and may introduce conformational changes in the protein. The linear responses of other residues are formed as in the following:

| (1) |

where F is a unit random force on selected residues, H−1 is the inverse of the Hessian matrix, and ΔR is the positional displacements of the N residues of the protein in three dimensions.

However, an ENM-based PRS approach cannot capture the differences in conformational dynamics caused by the changes in biochemical specificity of mutated amino acids because it is a coarse-grained model lacking biochemical detail. To compare the neutral and disease-associated variants with similar backbone structures, we replace the ENM basis of PRS with all-atom REMD simulations. Then after running equilibrated MD simulations, we obtain the covariance matrix of the C-alpha positions. The inverse of the Hessian matrix is replaced with the covariance matrix, G, derived from the MD trajectory, i.e.,

| (2) |

Because MD simulations take into account long-range interactions, solvation effects, and the biochemical specificity of amino acids, PRS using the covariance matrix obtained from REMD leads to insight beyond the scope of ENM-based PRS.

PRS quantifies the flexibility of a residue upon perturbation of other residues using the DFI. To compute DFI, we first apply a unit random external force on a single residue. The response vector of the positional displacements, ΔR, is computed using Eq. 1. To ensure each perturbation is isotropic, we perform the perturbation in ten different directions. The perturbation is repeated for each residue and we obtain the following perturbation matrix, A, which records the displacements for each residue upon the perturbation of another residue:

| (3) |

where denotes the magnitude of the displacement by residue i in response to the perturbation at residue j.

A given row of the perturbation matrix is the average displacement of a specific residue from its equilibrium position when all other residues are perturbed one at a time; a given column shows the response profile of all residues under the perturbation of specific residue. DFI is defined as the total displacement of residue i induced by perturbations placed on all residues in the protein and is calculated by taking the sum of row i in the matrix A (Eq. 3), which is normalized by the total displacement of all residues as in the following:

| (4) |

DFI is able to measure the impact of a nSNV on the structural dynamics of a protein at a specific position. In evolutionary-based approaches, simplistic measures that ignore dynamics such as the Grantham distance (57), a measure of the similarity of amino acid types by examining their side chain volume, polarity, and atomic composition, are frequently used.

To measure positions that are allosterically linked to functionally critical hinge points through interresidue dynamics, we introduced the metric functional-DFI (f-DFI). F-DFI is the ratio of the sum of the mean square fluctuation response of the residue j upon functional site perturbations (i.e., active or binding sites residues) to the response of residue j upon perturbations on all residues. F-DFI enables us to identify residues that are more sensitive to perturbations because of functionally critical residues. This index can be crucial to finding functionally important residues that are sequentially and spatially distant from the active or binding site, especially those involved in allosteric regulation, and it is expressed as in the following:

| (5) |

where is the response fluctuation profile of residue j upon perturbation of residue i. The numerator is the average mean square fluctuation response obtained over the perturbation of the functionally critical residues Nfunctional; the denominator is the average mean square fluctuation response over all residues. Below we discuss the specific case of the FTL. When computing the residues that are allosterically linked to regulatory loop L1, Nfunctional is the total number of residues in the regulatory loop L1, Nfunctional-L1, (residues 40–50) and Nfunctional-Cterminus (residues 162–168) are the residues of the C terminus.

Results and Discussion

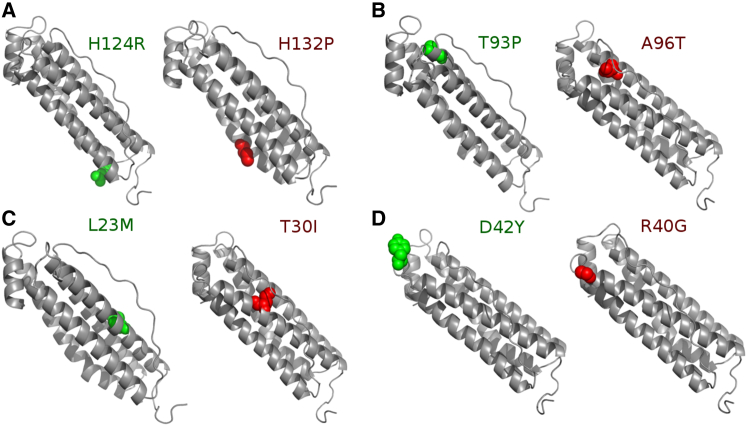

We investigated whether protein conformational dynamics can provide a mechanistic insight about why certain mutations lead to disease whereas others do not, irrespective of the fact that both types of mutations are very close in sequence and represent severe biochemical changes (i.e., high Grantham distance). To this aim, we have chosen a set of neutral (L23M, D42Y, T93P, and H124R) and disease associated (T30I, R40G, A96T, and H132P) nSNVs that have been observed in FTL (Fig. 2). Among those mutations, T30I and R40G nSNVs are associated with cataract syndrome (58,59). The A96T is associated with adult-onset basal ganglia disease (60). The H132P mutation is associated with Parkinson’s disease (61). These mutations are specifically chosen for multiple reasons: 1) there are known neutral nSNVs close in the sequence to the disease-associated nSNVs (e.g., L23M and T30I, R40G and D42Y, etc.); 2) the nSNVs occur in both secondary structural motifs and a flexible loop region; and 3) the neutral and disease variants span the biochemical spectrum for amino acids. For instance, the disease variant R40G mutates arginine, a positively charged amino acid, to glycine, the smallest amino acid type that is also considered nonpolar in certain scales. The neutral variant D42Y, which is close in sequence to R40G, also has a drastic change from a negatively charged amino acid to a hydrophobic amino acid.

Figure 2.

In addition to the wild-type of human ferritin we also studied the following neutral and disease-associated mutation pairs respectively: (A) H124R/H132P, (B) T93P/A96T, (C) L23M/T30I, and (D) D42Y/R40G. T30I and R40G mutations are associated with cataract syndrome. A96T is associated with adult-onset basal ganglia disease. H132P is associated with Parkinson's disease. Each pair was chosen because it was close in sequence, located in a secondary structure motif or the integral L1 loop, and covering the biochemical spectrum of amino acid mutations. Additionally, these mutations have not been correctly predicted as disease-associated mutations by other methods. To see this figure in color, go online.

Previous methods are unable to accurately predict these mutations. Using FoldX (62) to calculate the ΔΔG value, the change in folding stability upon mutation, it would be expected that disease variants should have larger ΔΔG values because they cause more destabilization. However, comparison of the ΔΔG values between disease and neutral variants show only a marginal change in stability. These results are not surprising as previous studies indicate that without at least limited backbone sampling, ΔΔG values are not accurate enough to distinguish disease versus neutral nSNVs (63). In addition to the lack of prediction accuracy via ΔΔG values, disease prediction servers are unable to accurately determine these mutations. Of the neutral nSNVs, Polyphen-2 (64) correctly predicts L23M and T93P mutations to be neutral, however, it fails in predicting D42Y and H124R as disease-associated. Likewise for the disease variants, Polyphen-2 incorrectly predicts the R40G and A96T nSNV.

There is a growing body of evidence linking the significant role of allosteric regulation in cellular function to disease and drug development in cases involving changes in structure and dynamics of proteins (65,66). Moreover, the mutations on the residue positions involved in allosteric pathways between active and allosteric sites may impair the function by disturbing allosteric communication, thus leading to different populations of active and inactive conformations (65,67). Therefore we investigated the role of structural dynamics on the phenotypic changes associated with genotypic changes (nSNVs) by simulating the monomeric form of wild-type FTL structure along with the four neutral and four diseases-associated mutations using replica-exchange molecular dynamics. Our goal is to calculate the dynamics profile of each position as they deviate from unbound equilibrium, shedding light on the response of specific residues to external forces experienced by the protein. Therefore we use a PRS approach (see Materials and Methods). In PRS, we introduce perturbations by applying a random external unit force on single residues as a first-order approximation to the forces exerted on a protein in a crowded cell environment, then we analyze the residue response fluctuation profile of the rest of the chain using linear response theory. It has been shown that PRS using an elastic network model or coupled with MD can be useful to 1) obtain conformational changes upon binding (22,41); 2) identify critical residues that mediate long-range communication through dynamic allostery (10,65,68–70); 3) predict a better binding affinity score through rapidly generating an ensemble of configurations for flexible docking (71–73); and 4) distinguish disease-associated and putatively neutral population variations in human proteome (27,28).

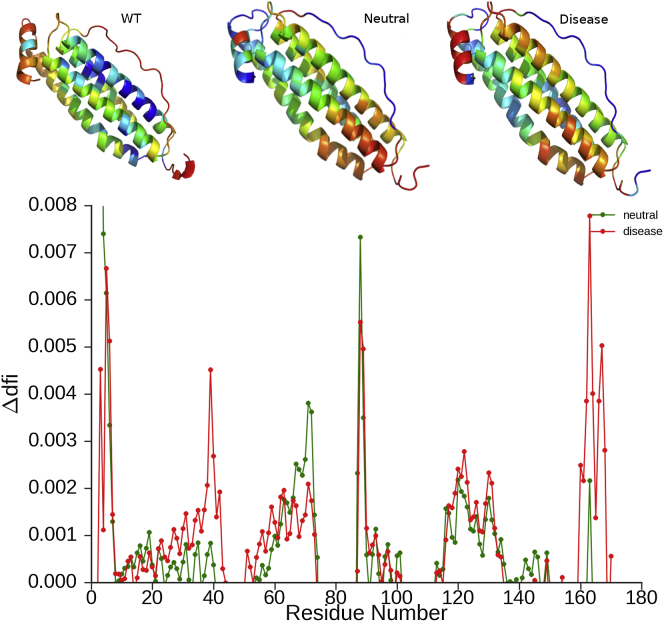

As defined, DFI is a relative value that indicates the average fluctuation response at a specific residue site upon perturbing the other residues one at a time. Sites with high DFI are more flexible and prone to feel the perturbation of other residues. Furthermore, because of this enhanced flexibility, regions encompassing several high DFI residues are expected to be more deformable overall. On the other hand, sites with low DFI may absorb and transfer the perturbation throughout the residue-dynamics communication network in a cascade fashion. They are usually involved with hinge parts of the protein that control the motion, similar to control knobs in machines. After generating the covariance matrix using REMD trajectories, we computed the DFI profiles for each mutant along with the wild-type and obtained the average DFI profile for disease and neutral mutants. Then we subtracted the wild-type DFI from each nSNV DFI profile to determine the change in DFI (ΔDFI) between mutant and wild-type. The average DFI profiles of the neutral and the disease-associated mutants are clearly distinct as shown by the color-coded ribbon diagrams (Fig. 3). The positions with low DFI are typically considered to be critical residues that control motion, i.e., hinges; an increase in the DFI value at these hinge points is interpreted as a loss of function. Interestingly, the plot of ΔDFI profiles for disease and neutral variants shows a distinct change in behavior at the region of regulatory loop L1 (residues 40−50) and the C terminus α-helix, where the DFI values of the disease profile are greatly increased relative to those of the neutral variant. Strikingly, this agrees with experimental findings that implicate the critical role of the C terminus and the nearby (spatially) regulatory loop (L1) residues in disease (53). Thus, an increase in DFI at these regions is correlated with a loss in functionality.

Figure 3.

(Top) The ribbon diagrams of the wild-type, neutral, and disease-associated nSNVs colored by their average DFI value within a spectrum of blue to red with blue being the lowest (most rigid) and red being the highest (most flexible). (Bottom) There is a significant increase in the DFI profile of the disease form at the L1 loop (residues 40–50) and the C-terminus. The ribbon diagram of the wild-type and disease forms correspondingly show a major increase in the DFI profile of the L1 loop and C-terminus. To see this figure in color, go online.

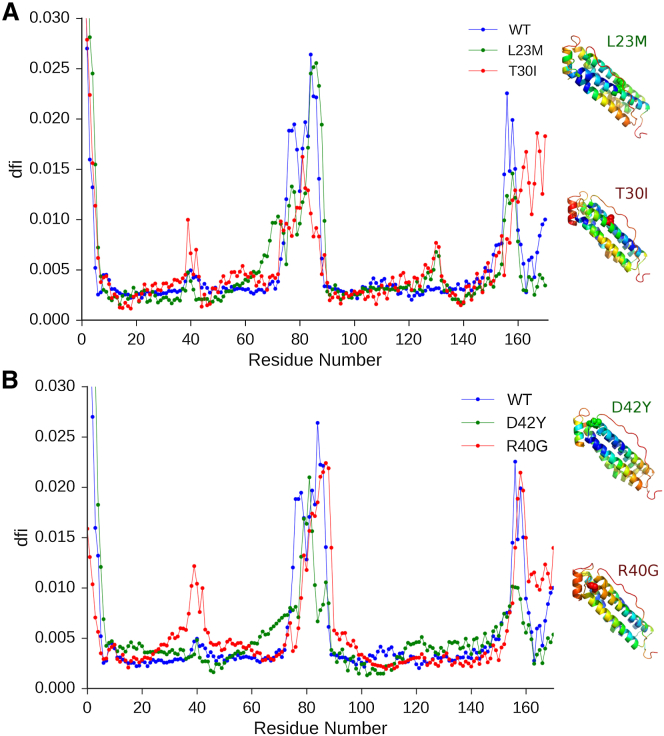

Furthermore, we examine each disease-associated and neutral nSNVs pair (close in sequence) to explore whether alterations in a DFI profile can give a mechanistic insight regarding how the disease develops. Cataract syndrome is caused by both T30I and R40G variants, however, the two neutral variants, close in sequence to these two disease-associated mutations, L23M and D42Y, are benign. Fig. 4A shows that whereas both L23M and T30I disrupt the ion binding region near region T130-T135, only the T30I variant drastically increases the flexibility, increasing the DFI values near the L1 loop and the C terminus α-helix. Experimental studies of cataract syndrome link only the mutations in the L1 loop region (residues 40−50) and near the C terminus α-helix (74) to the disease. Thus, the increase in the DFI at those regions is consistent with experimental findings. Given that both T30I and R40G cause the same disease, they could be expected to have similar DFI profiles. Fig. 4B shows that although the neutral D42Y nSNV exhibits behavior similar to the wild-type, it does not significantly disrupt the DFI profile, whereas the R40G profile is nearly identical to that of T30I, exhibiting the increase in DFI in loop L1 and the C terminus. Another interesting observation is that both disease-associated mutations are far separated from the C terminus end of the protein, yet they have an allosteric impact on the flexibility of C terminus end.

Figure 4.

(A) The DFI profile for the wild-type (blue), L23M neutral mutation (green), and the T30I disease mutation (red) with the corresponding ribbon diagrams color-coded with respect to their DFI profiles, with blue being the lowest (rigid) and red being the highest (flexible). The mutations are shown in spherical representation on the ribbon diagram. The DFI profile of T30I (red) is a signature of cataract syndrome with functional disruptions near the L1 loop (residues 40–50) and the C terminus helix, which is responsible for the gating mechanism. The increase in DFI leads to a loss of function of those residues because of their inability to transmit motion. (B) The DFI profile of the wild-type (blue), D42Y neutral mutation (green), and R40G disease-associated mutation (red) with the corresponding ribbon diagrams colored with respect to DFI profiles. The DFI profile of R40G is nearly identical to the DFI profile of T30I. To see this figure in color, go online.

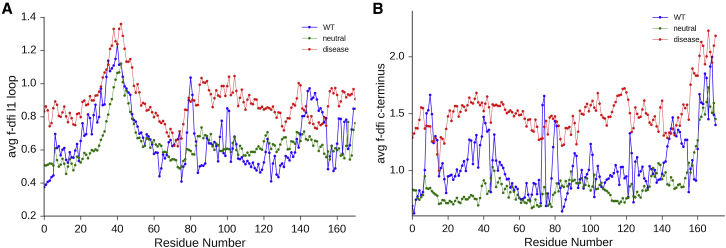

All disease-associated nSNVs tested led to increased DFI values around regulatory loop L1 and C terminus, as shown in Fig. 3. Most of the mutations (Fig. 3) are not located in those regions. The only special case is D42Y, which is very close to loop L1. However, the neutral mutation R40G is also in the same region of loop L1, and it does not impair the function. The allosteric network disruption by off-site nSNVs prompted us to investigate the role of allosteric residues whose dynamics are coupled to achieve functional regulation of FTL, because such coupling orchestrates functional behaviors through the residue interaction network of the given protein structure (9,71–73). For this analysis, we used the functional-DFI (f-DFI) metric for identifying the residues exhibiting significant fluctuation responses upon perturbation of functionally important sites in the protein (10). Thus, positions that are farther away from the functional site exhibiting high f-DFI values are allosteric sites, and dynamically linked to the functional sites. The f-DFI profiles of the positions that are allosterically linked to regulatory loop L1 were calculated for all the disease and neutral nSNVs. The average f-DFI profile for the disease and neutral mutations is obtained by taking the average over all the disease and neutral variants respectively. Previous DFI analysis showed that the L1 loop is a critical hinge point (i.e., exhibiting low DFI values) in the wild-type, and disease mutations cause an increase in DFI values in this region, thus making this critical control knob softer. In agreement with this picture, comparison of the neutral and disease f-DFI profiles with that of the wild-type provide a striking observation: the disease profile exhibits overall higher f-DFI values than the wild-type (Fig. 5A). The high f-DFI profile suggests that losing rigidity in a functionally critical hinge region impairs the dynamic allosteric residue coupling, leading to an overall flabby dysfunctional protein. Similarly, when we repeated the f-DFI analysis for the other critical hinge region, the C terminus, we observe the same behavior. The disease f-DFI profile is, in general, much greater suggesting the loss of dynamic allosteric residue coupling as a possible commonly observable trait for all disease-associated nSNVs (Fig. 5B) as may also be observed in somatic cancer mutations. Interestingly, in cancer distinguishing driver mutations from a preponderance of neutral passenger mutations is a challenging task (75). Moreover, more challenging cases occur with latent driver mutations, which act a passengers; yet, these mutations cooperatively drive disease with other emerging mutations (67). Thus, metrics such as DFI and f-DFI analysis may shed light on allosteric mechanisms these latent driver mutations play in disease development.

Figure 5.

The f-DFI profiles of the wild-type (blue), average neutral mutations (green), and average disease mutations (red). f-DFI measures the sensitivity of each position (i.e., residue response fluctuation) to the functionally important residues, in this case (A) the L1 loop (residues 40–50) and (B) C terminus involved in ion binding and the release of ions. f-DFI profiles of the disease mutations exhibit high overall values, suggesting the loss in allosteric control of these functional regions. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

Earlier studies on reconstruction of ancestral proteins suggest that nature uses changes in conformational dynamics to evolve at the molecular level (17,29,33,43). Our recent studies that incorporated the conformational dynamics of hundreds of monomeric and multimeric proteins have shown that protein dynamics has the power to distinguish between disease-associated nSNVs that affect biological function and neutral nSNVs that have no effect on function at a proteome scale (27,28). This large-scale analysis includes population variations implicated in diseases, functionally critical positions (catalytic and binding sites), and evolutionary rates of substitutions. It has produced concordant patterns, indicating that preservation of dynamic profiles of residues in a protein structure is crucial for maintaining the biological function. Based on these findings, we investigated how the dynamic profiles of residue positions are different between disease and neutral variants. We studied the conformational dynamics of the wild-type FTL along with four pairs of neutral and disease-associated variants. In each case, the neutral and disease-associated nSNVs are close in sequence and have a large biochemical change upon mutation. Comparison of the dynamic profiles among wild-type, disease, and neutral variants reveals that disease-associated mutations soften the functionally critical regions of human ferritin, leading to a flabby protein with loss of allosterically regulated conformational dynamics.

Author Contributions

T.J.G. and S.B.O. conceived and designed the experiments; T.J.G. and A.K. performed the experiments; A.K., T.J.G., S.B.O. analyzed the data; and A.K., T.J.G., and S.B.O. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded in part from NIH Grants (1U54GN0945999, LM011941-01 to SBO).

We also thank A2C2 at Arizona State University and XSEDE for CPU time. We also thank Brandon Butler for a careful review of the manuscript.

Editor: H. Jane Dyson

Footnotes

Avishek Kumar and Tyler J. Glembo contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Kolaczkowski B., Thornton J.W. Performance of maximum parsimony and likelihood phylogenetics when evolution is heterogeneous. Nature. 2004;431:980–984. doi: 10.1038/nature02917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huelsenbeck J.P., Hillis D.M., Jones R. Parametric bootstrapping in molecular phylogenetics: applications and performance. In: Ferraris J.D., Palumbi S.R., editors. Molecular Zoology: Advances, Strategies, and Protocols. Wiley-Liss; New York: 1996. pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollock D.D., Taylor W.R., Goldman N. Coevolving protein residues: maximum likelihood identification and relationship to structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;287:187–198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuffley C., Steel M. Links between maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony under a simple model of site substitution. Bull. Math. Biol. 1997;59:581–607. doi: 10.1007/BF02459467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaut B.S., Lewis P.O. Success of maximum likelihood phylogeny inference in the four-taxon case. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1995;12:152–162. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huelsenbeck J.P., Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenmesser E.Z., Bosco D.A., Kern D. Enzyme dynamics during catalysis. Science. 2002;295:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1066176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenmesser E.Z., Millet O., Kern D. Intrinsic dynamics of an enzyme underlies catalysis. Nature. 2005;438:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature04105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerek Z.N., Ozkan S.B. Change in allosteric network affects binding affinities of PDZ domains: analysis through perturbation response scanning. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y., Rader A.J., Jernigan R.L. Global ribosome motions revealed with elastic network model. J. Struct. Biol. 2004;147:302–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng W., Brooks B.R., Thirumalai D. Allosteric transitions in the chaperonin GroEL are captured by a dominant normal mode that is most robust to sequence variations. Biophys. J. 2007;93:2289–2299. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Gierasch L.M., Bahar I. Role of Hsp70 ATPase domain intrinsic dynamics and sequence evolution in enabling its functional interactions with NEFs. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin D.R., Ozkan S.B., Matyushov D.V. Dissipative electro-elastic network model of protein electrostatics. Phys. Biol. 2012;9:036004. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/9/3/036004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhabha G., Lee J., Wright P.E. A dynamic knockout reveals that conformational fluctuations influence the chemical step of enzyme catalysis. Science. 2011;332:234–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1198542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson C.J., Foo J.-L., Ollis D.L. Conformational sampling, catalysis, and evolution of the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:21631–21636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907548106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokuriki N., Tawfik D.S. Protein dynamism and evolvability. Science. 2009;324:203–207. doi: 10.1126/science.1169375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberles D.A., Teichmann S.A., Whelan S. The interface of protein structure, protein biophysics, and molecular evolution. Protein Sci. 2012;21:769–785. doi: 10.1002/pro.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maguid S., Fernandez-Alberti S., Echave J. Evolutionary conservation of protein vibrational dynamics. Gene. 2008;422:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang G.W., Altman R.B. Remote thioredoxin recognition using evolutionary conservation and structural dynamics. Structure. 2011;19:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng W., Brooks B.R., Thirumalai D. Low-frequency normal modes that describe allosteric transitions in biological nanomachines are robust to sequence variations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7664–7669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510426103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atilgan A.R., Durell S.R., Bahar I. Anisotropy of fluctuation dynamics of proteins with an elastic network model. Biophys. J. 2001;80:505–515. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76033-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maguid S., Fernández-Alberti S., Echave J. Evolutionary conservation of protein backbone flexibility. J. Mol. Evol. 2006;63:448–457. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chennubhotla C., Yang Z., Bahar I. Coupling between global dynamics and signal transduction pathways: a mechanism of allostery for chaperonin GroEL. Mol. Biosyst. 2008;4:287–292. doi: 10.1039/b717819k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiménez-Osés G., Osuna S., Houk K.N. The role of distant mutations and allosteric regulation on LovD active site dynamics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhabha G., Ekiert D.C., Wright P.E. Divergent evolution of protein conformational dynamics in dihydrofolate reductase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:1243–1249. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nevin Gerek Z., Kumar S., Banu Ozkan S. Structural dynamics flexibility informs function and evolution at a proteome scale. Evol. Appl. 2013;6:423–433. doi: 10.1111/eva.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler B.M., Gerek Z.N., Ozkan S.B. Conformational dynamics of nonsynonymous variants at protein interfaces reveals disease association: the role of dynamics in neutral and damaging nsSNVs. Proteins. 2015;83:428–435. doi: 10.1002/prot.24748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glembo T.J., Farrell D.W., Ozkan S.B. Collective dynamics differentiates functional divergence in protein evolution. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia Y., Levitt M. Simulating protein evolution in sequence and structure space. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liberles D.A. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2007. Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yokoyama S., Tada T., Britt L. Elucidation of phenotypic adaptations: molecular analyses of dim-light vision proteins in vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:13480–13485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802426105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harms M.J., Thornton J.W. Evolutionary biochemistry: revealing the historical and physical causes of protein properties. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:559–571. doi: 10.1038/nrg3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Risso V.A., Gavira J.A., Sanchez-Ruiz J.M. Hyperstability and substrate promiscuity in laboratory resurrections of Precambrian β-lactamases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:2899–2902. doi: 10.1021/ja311630a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duarte F., Amrein B.A., Kamerlin S.C.L. Modeling catalytic promiscuity in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013;15:11160–11177. doi: 10.1039/c3cp51179k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Seisdedos H., Ibarra-Molero B., Sanchez-Ruiz J.M. Probing the mutational interplay between primary and promiscuous protein functions: a computational-experimental approach. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khersonsky O., Roodveldt C., Tawfik D.S. Enzyme promiscuity: evolutionary and mechanistic aspects. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:498–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khersonsky O., Tawfik D.S. Enzyme promiscuity: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:471–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-030409-143718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen R.A. Enzyme recruitment in evolution of new function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1976;30:409–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.30.100176.002205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Brien P.J., Herschlag D. Catalytic promiscuity and the evolution of new enzymatic activities. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:R91–R105. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atilgan C., Atilgan A.R. Perturbation-response scanning reveals ligand entry-exit mechanisms of ferric binding protein. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atilgan C., Okan O.B., Atilgan A.R. How orientational order governs collectivity of folded proteins. Proteins. 2010;78:3363–3375. doi: 10.1002/prot.22843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zou T., Risso V.A., Ozkan S.B. Evolution of conformational dynamics determines the conversion of a promiscuous generalist into a specialist enzyme. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:132–143. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim H., Zou T., Wachter R.M. A hinge migration mechanism unlocks the evolution of green-to-red photoconversion in GFP-like proteins. Structure. 2015;23:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar S., Dudley J.T., Liu L. Phylomedicine: an evolutionary telescope to explore and diagnose the universe of disease mutations. Trends Genet. 2011;27:377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bamshad M.J., Ng S.B., Shendure J. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper D.N., Stenson P.D., Chuzhanova N.A. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) and its exploitation in the study of mutational mechanisms. In: Baxevanis A.D., Petsko G.A., Stein L.D., Stormo G.D., editors. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campagnoli M.F., Pimazzoni R., Ramenghi U. Onset of cataract in early infancy associated with a 32G-->C transition in the iron responsive element of L-ferritin. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2002;161:499–502. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-1019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curtis A.R., Fey C., Burn J. Mutation in the gene encoding ferritin light polypeptide causes dominant adult-onset basal ganglia disease. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:350–354. doi: 10.1038/ng571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dexter D.T., Carayon A., Marsden C.D. Alterations in the levels of iron, ferritin and other trace metals in Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases affecting the basal ganglia. Brain. 1991;114:1953–1975. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.4.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qian Z.M., Wang Q. Expression of iron transport proteins and excessive iron accumulation in the brain in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1998;27:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ke Y., Ming Qian Z. Iron misregulation in the brain: a primary cause of neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:246–253. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ponting C.P. Domain homologues of dopamine β-hydroxylase and ferric reductase: roles for iron metabolism in neurodegenerative disorders? Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1853–1858. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.17.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sugita Y., Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearlman D.A., Case D.A., Kollman P. AMBER, a package of computer programs for applying molecular mechanics, normal mode analysis, molecular dynamics and free energy calculations to simulate the structural and energetic properties of molecules. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mongan J., Simmerling C., Onufriev A. Generalized Born model with a simple, robust molecular volume correction. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007;3:156–169. doi: 10.1021/ct600085e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grantham R. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science. 1974;185:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4154.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vidal R., Ghetti B., Delisle M.B. Intracellular ferritin accumulation in neural and extraneural tissue characterizes a neurodegenerative disease associated with a mutation in the ferritin light polypeptide gene. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2004;63:363–380. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Z., Li C., Carter D.C. Structure of human ferritin L chain. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:800–806. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906018294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Orino K., Harada S., Watanabe K. Kinetic analysis of bovine spleen apoferritin and recombinant H and L chain homopolymers: iron uptake suggests early stage H chain ferroxidase activity and second stage L chain cooperation. Biometals. 2004;17:129–134. doi: 10.1023/b:biom.0000018379.20027.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Granier T., Comberton G., Précigoux G. Evidence of new cadmium binding sites in recombinant horse L-chain ferritin by anomalous Fourier difference map calculation. Proteins. 1998;31:477–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guerois R., Nielsen J.E., Serrano L. Predicting changes in the stability of proteins and protein complexes: a study of more than 1000 mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:369–387. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Subramanian S., Kumar S. Evolutionary anatomies of positions and types of disease-associated and neutral amino acid mutations in the human genome. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:306. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adzhubei I., Jordan D.M., Sunyaev S.R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. In: Haines J.L., Korf B.R., Morton C.C., Seidman C.E., Seidman J.G., Smith D.R., editors. Current Protocols in Human Genetics. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2013. pp. 7.20.1–7.20.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsai C.-J., Nussinov R. A unified view of “how allostery works.”. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cooper A., Dryden D.T. Allostery without conformational change. A plausible model. Eur. Biophys. J. 1984;11:103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00276625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nussinov R., Tsai C.-J. ‘Latent drivers’ expand the cancer mutational landscape. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015;32C:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nussinov R., Tsai C.-J. The design of covalent allosteric drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015;55:249–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu S., Huang W., Zhang J. The structural basis of ATP as an allosteric modulator. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nussinov R., Tsai C.-J., Liu J. Principles of allosteric interactions in cell signaling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:17692–17701. doi: 10.1021/ja510028c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bolia A., Gerek Z.N., Dev K.K. The binding affinities of proteins interacting with the PDZ domain of PICK1. Proteins. 2012;80:1393–1408. doi: 10.1002/prot.24034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bolia A., Woodrum B.W., Ghirlanda G. A flexible docking scheme efficiently captures the energetics of glycan-cyanovirin binding. Biophys. J. 2014;106:1142–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bolia A., Gerek Z.N., Ozkan S.B. BP-Dock: a flexible docking scheme for exploring protein-ligand interactions based on unbound structures. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:913–925. doi: 10.1021/ci4004927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hedges S.B., Dudley J., Kumar S. TimeTree: a public knowledge-base of divergence times among organisms. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2971–2972. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vogelstein B., Papadopoulos N., Kinzler K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]