Abstract

Human intestinal capillariasis is a rare parasitosis that was first recognized in the Philippines in the 1960 s. Parasitosis is a life threatening disease and has been reported from Thailand, Japan, South of Taiwan (Kaoh-Siung), Korea, Iran, Egypt, Italy and Spain. Its clinical symptoms are characterized by chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, borborygmus, marked weight loss, protein and electrolyte loss and cachexia. Capillariasis may be fatal if early treatment is not given. We reported 14 cases living in rural areas of Taiwan. Three cases had histories of travelling to Thailand. They might have been infected in Thailand while stayed there. Two cases had the diet of raw freshwater fish before. Three cases received emergency laparotomy due to peritonitis and two cases were found of enteritis cystica profunda. According to the route of transmission, freshwater and brackish-water fish may act as the intermediate host of the parasite. The most simple and convenient method of diagnosing capillariasis is stool examination. Two cases were diagnosed by histology. Mebendazole or albendezole 200 mg orally twice a day for 20-30 d is the treatment of choice. All the patients were cured, and relapses were not observed within 12 mo.

INTRODUCTION

Capillaria species parasitize many classes of vertebrates, although only 4 species described have been found in humans, namely Capillaria phillippinensis, Capillaria plica, Capillaria aerophila, and Capillaria hepatica[1]. C. philippinensis is a tiny nematode that was first described in the 1960 s as the causative agent of severe diarrheal syndromes in humans. In 1962, the first case of human intestinal capillariasis occurred in a previously healthy young man from Luzon (Philippines) who subsequently died. At autopsy, a large number of worms, later described as C. Philippinensis, were found in the large and small intestines[2]. The disease was first reported by Chitwood et al in 1964[3]. During the Philippine epidemic from 1967 to 1968, more than 1300 persons acquired the illness and 90 patients with parasitologically confirmed infections died[4]. In late 1978 and early 1979, another small outbreak was identified in northeastern Mindanao, the Phillippines, and about 50 persons acquired the infection[4]. Sporadic cases continued to appear in northern Luzon as well as in other areas where epidemics had occurred. The disease is also endemic in Thailand, and was first reported in 1973[5]. Sporadic cases have also been found in Iran[6], Egypt[7,8], Taiwan[9], Japan[10,11], Indonesia[12], Korea[13], Spain (probably acquired in Colombia)[14] and Italy (acquired in Indonesia)[15], indicating that this infection is widespread. Because the infection can result in a severe disease with a high mortality when untreated, early diagnosis is very important. Here we described 14 cases of human intestinal capillariasis found in Taiwan from 1983 to 2001.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

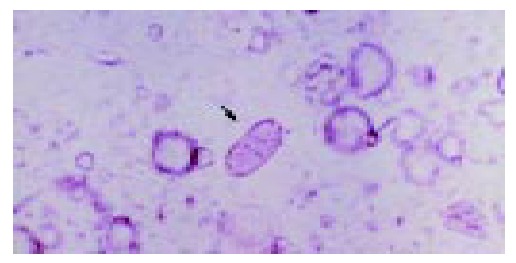

Since 1983, 14 cases have been diagnosed as intestinal capillariasis in Taiwan, all with the symptoms of chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, borborygmus and marked weight loss. All patients were hospitalized for examination and treatment. Their diagnosis was confirmed by eggs and/or larvae and/or adult C. philippinensis found in the feces of 5 patients. Two cases were recognized by a pathologist by histology of jejunum or ileum (Figure 1, Figure 2) with negative stool examination. Bacterial cultures of stool specimens were negative in all patients. The stool specimens were examined by formalin-ether concentration method. C. Philippinensis eggs were peanut-shaped with flattened bipolar plugs, 20×40 mm in size (Figure 3).

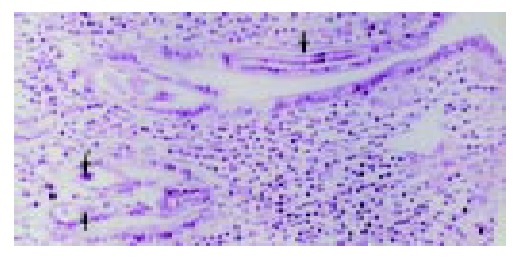

Figure 1.

C Philippinensis worms embedded in intestinal mu-cosa (arrow). Hematoxylin and eosin, × 200.

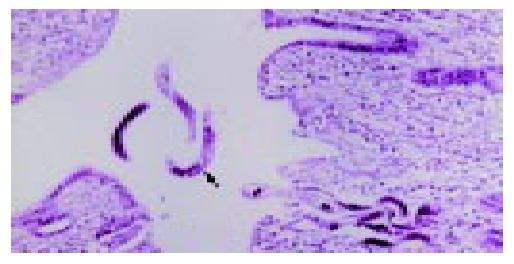

Figure 2.

Multiple longitudinal sections of C. philippinensis on mucosal surface and lumen. The longitudinal sections shows a row of stichocytes (arrow). Hematoxylin and eosin, × 200.

Figure 3.

Peanut-shaped eggs of C. philippinensis in feces with flattened bipolar plugs. × 160.

RESULTS

Fourteen cases, nine males and five females, were 36 to 76 years old when they were diagnosed as intestinal capillariasis (Table 1, Table 2). Three lived in Kaohsiung County and eleven in Taitung County. Seven of them were aborigines and two were brother and sister. Two of them had histories of travelling to Thailand. Two patients had history of eating raw or insufficiently cooked fresh-water fish. Four of 14 patients had mixed infection with Clonorchis sinensis or Strongyloides stercoralis whose eggs were also found in the feces.

Table 1.

Cheracteristics of seven patients with intestinal capillariasis reported in Tai-tung

| Case No. | Year Occurred | Occupation | Age (yr) | Sex | Travel history | Associated parasite | Treatment | Outcome |

| 1 | 1983 | Farmer | 76 | M | - | Clonorchis sinensis | Albendazole | Cure |

| 2 | 1987 | Merchant | 46 | M | - | - | Albendazole | Cure |

| 3 | 1988 | Housewife | 58 | F | Thailand | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 4 | 1990 | Housewife | 41 | F | - | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 5 | 1991 | Housewife | 36 | F | - | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 6 | 1991 | Farmer | 62 | M | - | Clonorchis sinensis | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 7 | 1991 | Housewife | 46 | F | - | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 8 | 1992 | Merchant | 53 | M | Thailand | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 9 | 1992 | Farmer | 45 | M | - | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 10 | 1995 | Farmer | 61 | M | - | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 11 | 1995 | Housewife | 45 | F | - | Strongyloides stercoralis | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 12 | 1999 | Farmer | 39 | M | - | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 13 | 2000 | Fisher-man | 69 | M | - | - | Mebendazole | Cure |

| 14 | 2001 | Farmer | 50 | M | - | Clonorchis sinensis | Mebendazole | Cure |

Table 2.

Clinical features and diagnostic method of seven patients with intestinal capillariasis reported in Tai-tung

| Case No. | Duration of onset to diagnosis | Diagnostic method | Chronic diarrhea | Abdominal Pain | Abdominal borborygmi | Body weight loss | Anemia | Hypoalbu minemia |

| 1 | 119 d | Stool ova | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | 2Y7 M | Stool ova | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | 6 M | Stool ova | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | 1Y3 M | Histology | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | 120 d | Histology | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | 70 d | Stool ova | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| 7 | 7 d | Stool ova | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| 8 | 65 d | Stool ova | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 9 | 34 d | Stool ova | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| 10 | 103 d | Stool ova | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| 11 | 66 d | Stool ova | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| 12 | 37 d | Histology | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| 13 | 25 d | Histology | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| 14 | 17 d | Stool ova | + | + | + | + | - | + |

Three cases received emergency laparotomy due to peritonitis and two of them were found to have jejunitis cystica profunda. Small bowel series and colonoscopic study revealed mild dilatation and thickened mucosa of jejunum and ileum, which suggested malabsorption. Laboratory findings revealed anemia, malabsorption of fats and carbohydrates and low serum levels of potassium, sodium, calcium and total protein. Mebendazole 200 mg twice a day for 20 d was given to 12 patients, while albendazole was given to the other two patients. All of them were cured and relapses were not observed within 12 mo following chemotherapy and supportive treatment.

DISCUSSION

Capillaria species parasitize many classes of vertebrates, although only 4 species have been found in humans, namely C. philippinensis, C. plica, C. aerophila, and C. hepatica[1]. C. philippinensis is a tiny nematode first described in the 1960 s as a pathogen inducing severe diarrheal syndromes in humans. In 1962, the first reported case of human intestinal capillariasis occurred in a previously healthy young man from Luzon in the Philippines, who subsequently died. At autopsy, a large number of worms were found in the large and small intestines[2]. Chitwood et al described this case in 1964[3]. There was an epidemic of the disease in the Philippines from 1967 to 1968, more than 1 300 persons acquired the illness, and 90 patients with parasitologically confirmed infection died[4]. In late 1978 and early 1979, another small outbreak was identified in northeastern Mindanao, Phillippines, with about 50 persons infected[4]. Sporadic cases continued to appear in northern Luzon and also in other areas where epidemics had occurred. The disease is endemic in Thailand, where it was first reported in 1973[5]. Sporadic cases have also been found in Iran[6], Egypt[7,8], Taiwan[9], Japan[10,11], Indonesia[12], Korea[13], Spain (probably acquired in Colombia)[14], and Italy (acquired in Indonesia)[12]. The parasite thus appears to be widespread. Because infection may result in severe disease with a high mortality when untreated, early diagnosis is very important. Infection with C. philippinensis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of malabsorption syndrome[15]. There was often a delay in diagnosis, averaging 4 mo and even longer in Taiwan, especially in non-endemic areas[16]. The delay was over a year in our cases.

It has been found that Capillaria species are closely related to Trichuris and Trichinella species[1], and the eggs of Trichuris trichiura and C. philippinensis are similar in appearance, although they can be differentiated by experienced observers[17]. Some individuals could be infected with both parasites, which further confuse the picture. In fact, 10 of the 11 patients described by Whaler et al[18] were infected with both T. trichiura and C. philippinensis. An inexperienced observer might confuse the eggs of Capillaria with those of T. trichiuria[1], although a correct parasitologic diagnosis could be made by finding characteristic peanut-shaped eggs with flattened bipolar plugs[2].

The source of C. philippinensis infection in our two patients was unclear, particularly as they had no travel history. In Thailand and the Philippines, the infection has been attributed to eating raw or insufficiently cooked fish harboring the larvae[2,19]. Hakka Chinese in Taiwan like to eat raw, freshwater fish, so they might be expected to have a significant incidence of infection if freshwater fish in Taiwan commonly host C. philippinensis. This is not the case, however. Our two patients lived in the southeastern part of Taiwan, closest to Luzon, so it was possible that the fish imported from the Philippines were the source of infection. Fish in markets in Taitung County, southeastern Taiwan, have been examined for C. philippinensis infection, but the results were negative. Recent findings suggested that fishing-eating birds might be the natural definitive hosts[20], including Bulbulcus ibis, Nyticorax nyticorax, and Ixobrychus sinensis, all of which have been found in Taiwan[21]. Therefore, the possibility of human infection acquired in Taiwan by direct or indirect ingestion of fresh-water fish with a larval stage of the parasite cannot be discounted.

Enteritis cystic profunda is a disorder with mucin-filled cystic spaces lined by non-neoplastic columnar epithelium in the wall of small intestine, predominantly the submucosa. The histology has been found to simulate mucinous carcinoma[22]. It has also been shown to occur in the esophagus[23] and stomach[24,25]. The irregular distribution of the glands and cysts with normal-appearing glandular epithelium containing mucus and Paneth’s cells were features suggestive of its benign nature[26].

Albendazole was presently considered the drug of choice for the treatment of human intestinal capilliariasis because it was effective against eggs, larvae, and adult worms[1,26]. However, for a major infection, mebendazole (200 mg orally twice a day for 20 d) was recommended as the treatment of choice. Attempts to reduce the standard schedule of mebendazole treatment (400 mg daily for 3 wk) have failed in Thailand. Our patients responded well to a standard course of mebendazole and had no evidence of relapse.

Convenient international travel and commercial globalization have facilitated the wide dissemination of infectious diseases, whether they are carried by human hosts or non-human vectors. Intestinal capillariasis needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with chronic diarrhea, borborygmus, abdominal pain, and marked weight loss.

Footnotes

Edited by Wang XL and Xu JY Proofread by Xu FM

References

- 1.Cross JH. Intestinal capillariasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:120–129. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross JH. Intestinal capillariasis. Parasitol Today. 1990;6:26–28. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90389-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chitwood MB, Valesquez C, Salazar NG. Capillaria philippinensis sp. n. (Nematoda: Trichinellida), from the intestine of man in the Philippines. J Parasitol. 1968;54:368–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross JH, Singson CN, Battad S, Basaca-Sevilla V. Intestinal capillariasis: epidemiology, parasitology and treatment. Proc R Soc Med Int Cong Symp Ser. 1979;24:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pradatsundarasar A, Pecharanónd K, Chintanawóngs C, Ungthavórn P. The first case of intestinal capillariasis in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1973;4:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoghooghi-Rad N, Maraghi S, Narenj-Zadeh A. Capillaria philippinensis infection in Khoozestan Province, Iran: case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;37:135–137. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.37.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youssef FG, Mikhail EM, Mansour NS. Intestinal capillariasis in Egypt: a case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:195–196. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansour NS, Anis MH, Mikhail EM. Human intestinal capillariasis in Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:114. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90398-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CY, Hsieh WC, Lin JT, Liu MC. Intestinal capillariasis: report of a case. Taiwan Yixuehui Zazhi. 1989;88:617–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukai T, Shimizu S, Yamamoto M. A case of intestinal capillariasis. Jpn Arch Int Med. 1983;3:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nawa Y, Imai JI, Abe T, Kisanuki H, Tsuda K. A case report of intestinal capillariasis. The second case found in Japan. Jpn J Parasitol. 1988;37:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chichino G, Bernuzzi AM, Bruno A, Cevini C, Atzori C, Malfitano A, Scaglia M. Intestinal capillariasis (Capillaria philippinensis) acquired in Indonesia: a case report. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:10–12. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SH, Hong ST, Chai JY, Kim WH, Kim YT, Song IS, Kim SW, Choi BI, Cross JH. A case of intestinal capillariasis in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:542–546. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dronda F, Chaves F, Sanz A, Lopez-Velez R. Human intestinal capillariasis in an area of nonendemicity: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:909–912. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.5.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paulino GB, Wittenberg J. Intestinal capillariasis: a new cause of a malabsorption pattern. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;117:340–345. doi: 10.2214/ajr.117.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang KP Human intestinal capillariasis (Capillaria philippinensis) in Taiwan. Zhonghua Minguo Xiaoerke Yixuehui Zazhi ; 39: 82-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaman V, Keong LA. Helminths in: Handbook of medical parasitology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. 1990:87–217. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whalen GE, Rosenberg EB, Strickland GT, Gutman RA, Cross JH, Watten RH. Intestinal capillariasis. A new disease in man. Lancet. 1969;1:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhaihulaya M, Indra-Ngarm S, Anathapruit M. Freshwater fishes of Thailand as experimental intermediate host for Cap-illaria philippinensis. Int J Parasitol. 1979;9:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhaibulaya M, Indra-Ngarm S. Amaurornis phoenicurus and Ardeola bacchus as experimental definitive hosts for Capillaria philippinensis in Thailand. Int J Parasitol. 1979;9:321–322. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(79)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cross JH, Basaca-Sevilla V. Experimental transmission of Capillaria philippinensis to birds. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:511–514. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyriakos M, Condon SC. Enteritis cystica profunda. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:77–85. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voirol MW, Welsh RA, Genet EF. Esophagitis cystica. Am J Gastroenterol. 1973;59:446–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.OBERMAN HA, LODMELL JG, SOWER ND. DIFFUSE HETEROTOPIC CYSTIC MALFORMATION OF THE STOMACH. N Engl J Med. 1963;269:909–911. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196310242691708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonde EC, Rodning CB. Gastritis cystica profunda. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:459–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson NJ, Rivera ES, Flores DJ. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with cervical adenocarcinoma and enteritis cystica profunda. West J Med. 1984;141:242–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]