Abstract

Metabolic cascades involving arachidonic acid (AA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) within brain can be independently targeted by drugs, diet and pathological conditions. Thus, AA turnover and brain expression of AA-selective cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), but not DHA turnover or expression of DHA-selective Ca2+-independent iPLA2, are reduced in rats given agents effective against bipolar disorder mania, whereas experimental excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation selectively increase brain AA metabolism. Furthermore, the brain AA and DHA cascades are altered reciprocally by dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) deprivation in rats. DHA loss from brain is slowed and iPLA2 expression is decreased, whereas cPLA2 and COX-2 are upregulated, as are brain concentrations of AA and its elongation product, docosapentaenoic acid (DPA).

Positron emission tomography (PET) has shown that the normal human brain consumes 17.8 and 4.6 mg/day, respectively, of AA and DHA, and that brain AA consumption is increased in Alzheimer disease patients. In the future, PET could help to determine how human brain AA or DHA consumption is influenced by diet, aging or disease.

Keywords: Phospholipid, Brain, Metabolism, PUFA, Phospholipase A2 (PLA2), Arachidonic, Docosahexaenoic, Diet, Lithium, Rat, Human, Bipolar disorder

1. Introduction

Normal brain metabolism, function and structure depend on maintaining homeostatic concentrations of the nutritionally essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) [1]. Disturbances in these concentrations or in the enzymes that regulate their metabolism have been associated with a number of human diseases, including Alzheimer disease [2] and bipolar disorder [3], and with altered behavior in animals [4].

Recent insights into brain PUFA metabolism have been accomplished with the integrated use of kinetic, analytical and molecular methods, in animals as well as in humans. This review briefly summarizes these methods and some results derived with them. These results suggest that DHA and AA turnover rates within brain phospholipids are regulated by independent sets of selective enzymes. Thus, the brain AA metabolic cascade [5] is downregulated in awake rats treated chronically with mood stabilizers that are effective against the mania of bipolar disorder [6], whereas it is upregulated while the DHA metabolic cascade is downregulated in rats fed, for 15 weeks, a diet low in n-3 PUFAs [7].

2. Kinetic methods

To quantify brain PUFA metabolism in vivo in rodents, a loosely restrained unanesthetized rodent is injected intravenously with a radiolabeled PUFA bound to serum albumin. Labeled and unlabeled unesterified PUFA concentrations are quantified in plasma at fixed times until the animal is anesthetized and its brain is removed after being subjected to high-energy microwaving to stop metabolism, or simply is removed and frozen. Lipids are extracted from the microwaved brain and labeled and unlabeled PUFA concentrations are determined in the brain unesterified fatty acid, acyl-CoA and phospholipid pools. The frozen brain is cut into serial coronal slices for quantitative autoradiography, or is used for molecular or enzyme activity analyses. PUFA half-lives due to metabolic loss can be determined by injecting a radiolabeled PUFA intracerebrally, and measuring PUFA-specific activity in individual phospholipids of microwaved brain as a function of time [8]. Positron emission tomography (PET) with intravenously injected positron-emitting [1-11C]AA or [1-11C]DHA can be used to measure human brain consumption of AA and DHA [2,9,10].

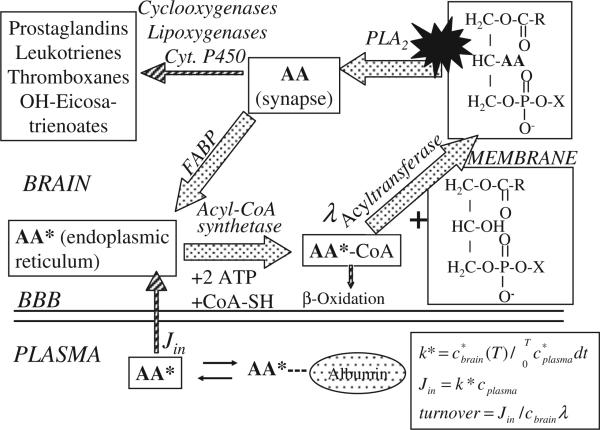

3. Compartmental representation of brain AA cascade

Fig. 1 illustrates plasma–brain exchange of AA and of its intravenously injected radiolabel (designated as AA*), as well as pathways and compartments of the brain AA metabolic cascade. The cascade is initiated by the activation of a phospholipase A2 (PLA2), which releases unesterified AA from the stereospecifically numbered-2 position of synaptic membrane phospholipid [11]. PLA2 activation is coupled by a G-protein or Ca2+ to activation of certain neuroreceptors [12]. A comparable figure can be written for the DHA cascade [13].

Fig. 1.

Model of brain arachidonic acid (AA) cascade. AA at the stereospecifically numbered-2 position of a phospholipid is liberated by activation (star) of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) at the synapse. A small fraction of the liberated AA is converted to bioactive eicosanoids. The remainder diffuses to the endoplasmic reticulum while bound to a fatty acid binding protein (FABP), from where it is converted to arachidonoyl-CoA by acyl-CoA synthetase with the consumption of 2 ATPs, then reesterified by an acyltransferase. Unesterified AA in the endoplasmic reticulum exchanges freely and rapidly with unesterified AA in plasma, into which labeled AA (AA*) has been injected. Equations for calculating kinetic parameters are shown in right lower corner. Adapted from [35].

After its release by PLA2, AA is transported to the endoplasmic reticulum and cycled back into phospholipid by the serial actions of acyl-CoA synthetase and acyl transferase. A small fraction however is metabolized to eicosanoids and other products, or undergoes β-oxidation after being transferred to mitochondria from the arachidonoyl-CoA pool by carnitine palmitoyltransferase. Due to the differential affinity of this enzyme for acyl-CoA moieties [14], AA and DHA are largely (90%) reacylated into brain phospholipid and palmitic acid (16:0) is 50% β-oxidized, but linoleic acid (LA, 18: 2n-6) and α-linolenic acid (α-LNA, 18: 3n-3) are almost entirely (about 99%) β-oxidized after entering brain [15,16]. Circulating AA* rapidly reaches equilibrium with brain arachidonoyl-CoA during its intravenous infusion [17].

The coefficient k* (ml/s/g wet wt brain) of incorporation of unesterified plasma AA into stable brain lipids (mostly phospholipids) is given as

| (1) |

where c*brain(T) (nCi/g) is the labeled esterified brain AA concentration at time T (usually 5 min) after tracer injection, and the denominator (the input function) is integrated plasma radioactivity due to AA*, c*plasma (nCi/ml), between the start of injection at time t = 0 and T.

The rate of incorporation Jin (nmol/s/g brain) of unesterified unlabeled plasma AA into brain equals the product of the unesterified unlabeled plasma AA concentration cplasma, and the incorporation coefficient k*,

| (2) |

k* and Jin are unaffected by changes in cerebral blood flow [18], and thus solely reflect brain metabolism. AA and DHA cannot be synthesized de novo in brain from 2-carbon fragments [19] or significantly converted from LA (18:2n-6) and α-LNA (18:3n-3), respectively [15,16]. Thus, Jin for AA and DHA represents their respective rates of metabolic consumption by brain [20].

AA turnover in brain phospholipids due to deacylation–reacylation (Fig. 1) [21] is given as

| (3) |

where cbrain (nmol/g) equals the unlabeled esterified PUFA concentration in stable brain lipid, and the dilution factor λ equals the steady-state-specific activity of the precursor arachidonoyl-CoA pool divided by plasma AA-specific activity.

4. AA and DHA cascades regulated by separate selective enzymes

AA recycling (Fig. 1), and DHA recycling [13] appear to be independent processes that can be selectively targeted by drugs, diet or disease, as they are regulated by different enzymes. Three major PLA2 enzymes have been described in mammalian brain: (1) an AA-selective cytosolic phospholipase (cPLA2) (85 kDa, Type IVA) that requires <1 μM Ca2+ for translocation to the membrane plus phosphorylation for activation; (2) an AA-selective secretory PLA2 (sPLA2) (14kDa, Type IIA), which is also Ca2+ (20 mM) dependent; (3) and a Ca2+-independent PLA2 (iPLA2) (101 kDa, Type VIA) thought to be selective for DHA [22,23]. cPLA2 colocalizes and is coupled with cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 at postsynaptic sites [24–26], whereas iPLA2 is found at these sites and in astrocytes. Acyl-CoA synthetases also can be selective for AA or DHA [27,28].

The brain AA but not the DHA cascade is downregulated in rats chronically given antibipolar disorder drugs (see below), whereas the AA cascade but not the DHA cascade is upregulated by experimental neuroinflammation or excitotoxicity [29–31]. The two cascades are affected reciprocally (the AA cascade is upregulated while the DHA cascade is diminished) in rats fed an n-3 PUFA deficient diet [7], and in mice in which the gene for α-synuclein, a protein involved in Parkinson disease, has been knocked out [32].

5. Selective targeting of the rat brain AA cascade by mood stabilizers

Bipolar disorder is a life-long neuropsychiatric disease that consists of repeated cycles of manic and depressive episodes (Bipolar I) or of hypomanic and depressive episodes (Bipolar II). It affects 1–2% of the US population, appears initially in young adults, and has a 10–20% lifetime incidence of suicide. Agents called “mood stabilizers” are used to treat the disease [33]. Of these, lithium, carbamazepine [5-carbamoyl-5H-dibenz[b,f]azepine] and valproic acid [2-propylpentanoic acid] are FDA-approved for treating bipolar mania, whereas lamotrigine [6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine-3,5-diamine] is approved for bipolar depression and rapid cycling. A common mechanism that has been suggested to explain the action of each of the three antimanic agents is downregulation of the brain AA cascade [6,34,35].

Lithium, valproic acid or carbamazepine, when administered chronically to rats to produce plasma concentrations therapeutically relevant to bipolar disorder, reduced turnover (Eq. (3)) of AA but not of DHA or palmitic acid in brain phospholipids (Table 1). The effect of lithium and carbamazepine corresponded to reduced transcription of AA-selective cPLA2 and reduced binding of its transcription factor, activator protein-2 (AP-2). iPLA2 and sPLA2 were unaffected. Valproate's reduction of AA turnover resulted from its inhibiting an AA-selective microsomal acyl-CoA synthetase, thus acylation of AA to arachidonoyl-CoA (Fig. 1). Each of the three agents reduced the brain COX-2 activity [6], with valproate doing so by downregulating COX-2 transcription and the COX-2 transcription factor, NF-kB. Lamotrigine did not alter AA turnover but did reduce COX-2 transcription, thus downregulating part of the AA cascade. Topiramate [2,3:4,5-di-O-isopropylidene-β-D-fructopyranose sulfamate], an anticonvulsant suggested by initial phase II trials to be effective against bipolar disorder, but later proven ineffective in phase III trials [36], did not significantly change any brain AA or DHA cascade marker. These results suggest that antimanic bipolar drugs downregulate AA turnover and the enzymes that regulate turnover, and that bipolar mania is associated with upregulated brain AA metabolism.

Table 1.

Effective anti-bipolar agents downregulate parts of the rat brain arachidonic acid cascade

| Treatment | AA turnover | DHA turnover | cPLA2 mRNA, protein, activityf | sPLA2 mRNA, protein, activity | iPLA2 mRNA, protein, activity | AA-selective acyl-CoA synthetase activity | COX-2 protein and/or activity | PGE2e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithiuma | ↓ | Nc | ↓ | Nc | Nc | Nc | ↓ | ↓ |

| Carbamazepinea | ↓ | Nc | ↓ | Nc | Nc | Nc | ↓ | ↓ |

| Valproatea | ↓ | Nc | Nc | Nc | Nc | ↓ | ↓ +mRNAd | ↓ |

| Lamotrigineb | Nc | - | Nc | Nc | Nc | - | ↓ +mRNA | - |

| Topiramatec | Nc | Nc | Nc | Nc | Nc | - | Nc | Nc |

Nc, no change; -, not tested.

Preferred for bipolar mania.

Preferred for bipolar depression.

Ineffective in phase III trials.

COX-1 mRNA and TXB2 also decreased; accompanied by reduced binding NF- κB.

Formed preferentially via COX-2.

Accompanied by reduced binding of AP-2.

6. Dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation upregulates the arachidonic cascade but downregulates the DHA cascade

The brain AA and DHA cascades can be altered reciprocally by diet or genetic manipulation [32]. With regard to diet, feeding rats an n-3 PUFA deficient diet compared with an adequate diet (containing 0.2% and 4.6% α-LNA, respectively, but no DHA) for 15 weeks post-weaning, increased mRNA and protein levels of AA-selective cPLA2 and of sPLA2 and COX-2, but reduced expression of iPLA2 and COX-1 [7]. These changes were accompanied by increased brain concentrations of esterified AA and its elongation product, docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, 22:5n-6), and by slowed DHA metabolic loss from brain [8,37].

7. Quantifying regional PUFA consumption by the human brain

The rates of incorporation of AA and DHA from plasma into brain, Jin (Eq. (2)), equal their respective rates of metabolic consumption by brain (see above). Consumption rates by brain have been estimated with PET in healthy human volunteers [9,10] as 17.8 mg/day for AA and 4.6 mg/day for DHA.

PET also showed that brain AA consumption was higher in patients with Alzheimer disease than in age-matched controls [2]. The elevated consumption is consistent with evidence of inflammation and excitotoxicity in the postmortem brain from Alzheimer patients [38], as it also occurs in animal models of neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity.

8. Discussion

Radiotracer methods and kinetic models have been used to show that AA and DHA turnover rates in rat brain phospholipids are rapid and energy consuming. The recycling (deacylation–reacylation) processes of the two PUFAs appear independent of each other, as they are regulated by independent sets of PLA2, acyl-CoA synthetase and possibly acyltransferase enzymes, and can be independently targeted by drugs, diet or disease. AA recycling is reduced by chronic administration to rats of agents effective against mania in bipolar disorder, in association with reduced brain expression of AA-selective cPLA2 or acyl-CoA synthetase, and of COX-2. DHA metabolism and metabolic enzymes are unaffected. In contrast, brain AA but not DHA cascade markers are upregulated in rat models of neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity.

Reciprocal changes in the rodent brain AA and DHA cascades can be produced by dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation or by genetic manipulation. Feeding a low n-3 PUFA diet to rats for 15 weeks reduced brain DHA metabolic loss and expression of DHA-selective iPLA2 and of COX-1, but increased brain n-6 PUFA (AA plus DPA) concentrations and expression of cPLA2, sPLA2 and COX-2. Mice deficient in the α-synuclein gene have downregulated brain AA cascade markers but upregulated DHA cascade markers.

Because AA and DHA cannot be synthesized de novo in vertebrate tissue, nor converted from their respective LA and α-LNA precursors, their rates of incorporation from plasma into brain, Jin (Eq. (2)), measured following the intravenous injection of their radiolabel, equal their respective rates of metabolic consumption by brain. PET was used to show that brain consumption rates in healthy human volunteers equal 17.8 mg/day for AA, and 4.6 mg/day for DHA. This DHA consumption rate represents 2.5–5% of the estimated average daily dietary intake of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and DHA in the United States, 100–200 mg/day [39]. The AA consumption rate is increased in patients with Alzheimer disease, consistent with evidence for neuroinflammation and upregulated AA-selective enzymes in the postmortem Alzheimer brain.

In the future, AA and DHA consumption rates could be measured with PET in relation to human aging, diet and various neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. It would be of interest to see if the AA consumption was elevated in the manic phase of bipolar disorder, insofar as effective antimanic drugs downregulate AA metabolism in experimental animals.

Acknowledgement

The author (S. Rapoport) has no conflicts of interest regarding this work. This work was fully supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- DPA

docosapentaenoic acid

- LA

linoleic acid

- α-LNA

α-linolenic acid

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- cPLA2

cytosolic phospholipase A2

- sPLA2

secretory PLA2

- iPLA2

calcium-independent PLA2

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

References

- 1.Contreras MA, Rapoport SI. Recent studies on interactions between n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in brain and other tissues. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2002;13:267–272. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esposito GI, Giovacchini G, Liow J-S, Bhattacharjee A, Greenstein D, Schapiro M, Hallett M, Herscovith P, Eckleman W, et al. Imaging neuroinflammation in Alzheimer disease with radiolabeled arachidonic acid and PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2008;49(9):1414–1421. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.049619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao JS, Kim EM, Lee HJ, Rapoport SI. Up-regulated arachidonic acid cascade enzymes and their transcription factors in post-mortem frontal cortex from bipolar disorder patients. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 2007 797.5/Z4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demar JC, Jr., Ma K, Bell JM, Igarashi M, Greenstein D, Rapoport SI. One generation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid deprivation increases depression and aggression test scores in rats. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47(1):172–180. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500362-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimizu T, Wolfe LS. Arachidonic acid cascade and signal transduction. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao JS, Lee HJ, Rapoport SI, Bazinet RP. Mode of action of mood stabilizers: is the arachidonic acid cascade a common target? Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13(6):585–596. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao JS, Ertley RN, DeMar JC, Jr., Rapoport SI, Bazinet RP, Lee H-J. Dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation alters expression of enzymes of the arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid cascades in rat frontal cortex. Mol. Psychiatry. 2007;12(2):151–157. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeMar JC, Jr., Ma K, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Half-lives of docosahexaenoic acid in rat brain phospholipids are prolonged by 15 weeks of nutritional deprivation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Neurochem. 2004;91(5):1125–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovacchini G, Lerner A, Toczek MT, Fraser C, Ma K, DeMar JC, Herscovitch P, Eckelman WC, Rapoport SI, et al. Brain incorporation of 11C-arachidonic acid, blood volume, and blood flow in healthy aging: a study with partial-volume correction. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;45(9):1471–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umhau JC, Zhou W, Polozova A, Demar J, Bhattacharjee A, Ma K, Esposito G, Rapoport SI, Eckelman W, et al. Human brain incorporation of docosahexaenoic acid measured using PET. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapoport SI. In vivo fatty acid incorporation into brain phosholipids in relation to plasma availability, signal transduction and membrane remodeling. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2001;16(2–3):243–261. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:2-3:243. discussion 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rapoport SI. In vivo approaches to quantifying and imaging brain arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid metabolism. J. Pediatr. 2003;143(4 Suppl):S26–S34. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rapoport SI, Rao JS, Igarashi M. Brain metabolism of nutritionally essential polyunsaturated fatty acids depends on both the diet and the liver. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007;77(5–6):251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavino VC, Cordeau S, Gavino G. Kinetic analysis of the selectivity of acylcarnitine synthesis in rat mitochondria. Lipids. 2003;38(4):485–490. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demar JC, Jr., Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Alpha-linolenic acid does not contribute appreciably to docosahexaenoic acid within brain phospholipids of adult rats fed a diet enriched in docosahexaenoic acid. J. Neurochem. 2005;94(4):1063–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeMar JC, Jr., Lee HJ, Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI, Bazinet RP. Brain elongation of linoleic acid is a negligible source of the arachidonate in brain phospholipids of adult rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1761(9):1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Washizaki K, Smith QR, Rapoport SI, Purdon AD. Brain arachidonic acid incorporation and precursor pool specific activity during intravenous infusion of unesterified [3H]arachidonate in the anesthetized rat. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:727–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang MC, Arai T, Freed LM, Wakabayashi S, Channing MA, Dunn BB, Der MG, Bell JM, Sasaki T, et al. Brain incorporation of [1-11C]-arachidonate in normocapnic and hypercapnic monkeys measured with positron emission tomography. Brain Res. 1997;755:74–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holman RT. Control of polyunsaturated acids in tissue lipids. J. Am Coll. Nutr. 1986;5:183–211. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1986.10720125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapoport SI, Chang MC, Spector AA. Delivery and turnover of plasma-derived essential PUFAs in mammalian brain. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:678–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun GY, MacQuarrie RA. Deacylation–reacylation of arachidonoyl groups in cerebral phospholipids. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1989;559:37–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb22597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A(2) enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1488(1–2):1–19. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strokin M, Sergeeva M, Reiser G. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid release in rat brain astrocytes is mediated by two separate isoforms of phospholipase A2 and is differently regulated by cyclic AMP and Ca2+ Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;139:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufmann WE, Worley PF, Pegg J, Bremer M, Isakson P. COX-2, a synaptically induced enzyme is expressed by excitatory neurons at postsynaptic sites in rat cerebral cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:2317–2321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong WY, Sandhya TL, Horrocks LA, Farooqui AA. Distribution of cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 in the normal rat brain. J. Hirnforsch. 1999;39:391–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ong WY, Yeo JF, Ling SF, Farooqui AA. Distribution of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) in monkey brain. J. Neurocytol. 2005;34(6):447–458. doi: 10.1007/s11068-006-8730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Horn CG, Caviglia JM, Li LO, Wang S, Granger DA, Coleman RA. Characterization of recombinant long-chain rat acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 3 and 6: identification of a novel variant of isoform 6. Biochemistry;2005;44(5):1635–1642. doi: 10.1021/bi047721l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazinet RP, Weis MT, Rapoport SI, Rosenberger TA. Valproic acid selectively inhibits conversion of arachidonic acid to arachidonoyl-CoA by brain microsomal long-chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetases: relevance to bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2006;184(1):122–129. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao JS, Ertley RN, Rapoport SI, Bazinet RP, Lee HJ. Chronic NMDA administration to rats up-regulates frontal cortex cytosolic phospholipase A2 and its transcription factor, activator protein-2. J. Neurochem. 2007;102(6):1918–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HJ, Rao JS, Chang L, Rapoport SI, Bazinet RP. Chronic N-methyl-D-aspartate administration increases the turnover of arachidonic acid within brain phospholipids of the unanesthetized rat. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49(1):162–168. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700406-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberger TA, Villacreses NE, Hovda JT, Bosetti F, Weerasinghe G, Wine RN, Harry GJ, Rapoport SI. Rat brain arachidonic acid metabolism is increased by a 6-day intracerebral ventricular infusion of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:1168–1178. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golovko MY, Rosenberger TA, Feddersen S, Faergeman NJ, Murphy EJ. Alpha-synuclein gene ablation increases docosahexaenoic acid incorporation and turnover in brain phospholipids. J. Neurochem. 2007;101(1):201–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression. second ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang MC, Grange E, Rabin O, Bell JM, Allen DD, Rapoport SI. Lithium decreases turnover of arachidonate in several brain phospholipids. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;220:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13264-x. Erratum in: Neurosci Lett 1997 1931, 1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapoport SI, Bosetti F. Do lithium and anticonvulsants target the brain arachidonic acid cascade in bipolar disorder? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:592–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kushner SF, Khan A, Lane R, Olson WH. Topiramate monotherapy in the management of acute mania: results of four double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(1):15–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Igarashi M, DeMar JC, Jr., Ma K, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Upregulated liver conversion of alpha-linolenic acid to docosahexaenoic acid in rats on a 15 week n-3 PUFA-deficient diet. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48(1):152–164. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600396-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. NSAIDs and Alzheimer disease: epidemiological, animal model and clinical studies. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007;28(5):639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kris-Etherton PM, Taylor DS, Yu-Poth S, Huth P, Moriarty K, Fishell V, Hargrove RL, Zhao G, Etherton TD. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in the food chain in the United States. Am J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;71(1 Suppl):179S–188S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.179S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]