Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in Asian patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and to assess prognostic variables on overall post-recurrence survival time.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who underwent secondary cytoreduction at the Gynaecological Cancer Center at the KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore, between 1999 and 2009. Eligible patients included those who had been firstly treated by primary cytoreductive surgery and followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and had a period of clinical remission of at least six months and subsequently underwent secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrence. Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate various variables influencing the overall survival.

Results

Twenty-five patients met our eligibility criteria. The median age was 52 years (range=31–78 years). The median time from completion of primary treatment to recurrence was 25.1 months (range=6.4–83.4). Secondary cytoreduction was optimal in 20 of 25 patients (80%). The median follow-up duration was 38.9 months (range=17.8–72.4) and median overall survival time was 33.1 months (95% confidence interval, 15.3–undefined.). Ten (40.0%) patients required bowel resection, but no end colostomy was performed. One (4.0%) patient had wedge resection of the liver, one (4.0%) had a distal pancreatectomy, one (4.0%) had a unilateral nephrectomy, and one (4.0%) had adrenalectomy. There were no operative deaths. The overall survival of patients who responded to secondary cytoreductive surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy was significantly longer than those patients who did not respond to the treatment. Of those patients who responded to the surgical management, patients with clear cell carcinoma fared well compared to those with the endometrioid, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and papillary serous type (p<0.001). Complete secondary cytoreductive surgery appeared to have some relationship to overall survival but was not statistically significant.

Conclusion

In carefully selected patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, optimal cytoreductive surgery is possible and in a subgroup of patients who respond to surgery and chemotherapy survival is significantly longer.

Keywords: Ovarian Cancer, Cytoreduction Surgical Procedures, Debulking Surgical Procedures

Introduction

The role of primary cytoreductive surgery in the management of ovarian cancer is well established. It is known that complete cytoreductive surgery enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy by decreasing the cell clones that are resistant. Also, chemotherapy is delivered better to a small and well-vascularised residual tumor.1 Despite the standard treatment of primary cytoreduction and systemic chemotherapy, 70–90% of patients develop recurrent disease.2 Patients who have recurrence after six months of primary treatment are known to be platinum sensitive and hence most often rechallenged with platinum-based chemotherapy with various response rates due to the heterogeneity of the recurrent disease.

The role of surgery in the management of recurrent ovarian cancer has not been well established. Recent literature shows that in a selected group of patients, secondary cytoreductive surgery improves the prognosis.2-5 The two most consistent factors showing favorable outcome in patients undergoing secondary cytoreductive procedure were prolonged treatment-free survival (first recurrence from six months to 24 months) and postoperative residual disease, described as "<0.5mm," "microscopic," or "none."3-6 A meta-analysis by Bristow et al,7 supports the role of secondary cytoreductive surgery and proved that residual disease after debulking surgery is an important determinant of survival. New surgical options are emerging for selected patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, such as complete cytoreductive surgery including peritonectomy and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). These surgeries aim at achieving minimal or no residual disease and targeting the remaining residual disease with heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Again, this is based on the principle of using aggressive primary cytoreductive surgery with intraperitoneal chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer. Chi et al,8 demonstrated that along with traditional primary cytoreductive surgery, incorporating procedures such as resection of diaphragm peritonectomy, splenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, partial hepatectomy, cholecystectomy, and portal caval dissection in order to address tumor deposits in the upper abdomen has led to improved five-year progression–free survival.

The question of whether a change in the surgical paradigm should occur for recurrent ovarian cancer remains a topic of debate. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate our experience with secondary cytoreductive surgery for Asian patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and to evaluate various prognostic variables on overall post-recurrence survival time.

Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, the Gynaecological Cancer Center at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore, database was reviewed to identify patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who underwent secondary cytoreductive surgery from 1999 to 2009. Only those patients with epithelial ovarian cancer who had primary surgery followed by platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy and who were in clinical remission for six months were included in the study. All patients with recurrent ovarian cancer were presented at multidisciplinary tumor board meeting and, based on their clinical and radiological findings, patients who were deemed to have the resectable disease were selected for secondary cytoreductive surgery. The criteria for optimal cytoreductive surgery varied during the study period, before 2002 it was taken as <2cm and after that it was <1cm. Following surgery, patients were treated with a platinum-based chemotherapy combination and were changed to second- or third-line regimens based on their response. Twenty-five patients were identified from the database that fulfilled our criteria. Data were retrieved for age, details of primary surgery, stage, histological type, grade, adjuvant chemotherapy treatment, secondary debulking surgery if optimal or sub-optimal, follow-up, and survival outcome.

Disease-free interval (DFI) was calculated as the time (in months) from the date of completion of chemotherapy following primary cytoreductive surgery to the date of recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time (in months) from the date of completion of chemotherapy following secondary cytoreductive surgery to the date of death from all causes or censored at the date of last follow-up. Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated as the time (in months) from the date of completion of chemotherapy following secondary cytoreductive surgery to the date of recurrence or death from all causes, or censored at date of last follow-up. Patients who had progressive disease following secondary cytoreductive surgery were excluded from the analysis of DFS. Median follow-up duration was estimated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to determine the survival functions for DFI, OS, and DFS. Median DFI, OS, and DFS were derived, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the log-log method. One-, two- and three-year survival rates were also derived from the Kaplan-Meier survivor function. The log-rank test was used to determine if there was a difference in survival curves between different groups of patients. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.050 was taken as significant. All analyzes were performed using Stata 9.0 software (StataCorp, Texas, US).

Results

During the study period, 25 patients were identified who underwent secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer. Demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients at the time of diagnosis of recurrence are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics at recurrence.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at initial diagnosis (years) | |

| Median (range) | 52 (31–78) |

| Primary surgery | |

| Optimal | 20 (80.0) |

| Suboptimal | 5 (20.0) |

| Disease stage | |

| I | 7 (28.0) |

| II | 3 (12.0) |

| III | 13 (52.0) |

| IV | 0 (0) |

| Unstaged | 2 (8.0) |

| Grade of the disease | |

| Well-differentiated | 5 (20.0) |

| Moderately differentiated | 10 (40.0) |

| Poorly differentiated | 10 (40.0) |

| Histology | |

| Serous | 11 (44.0) |

| Endometroid | 7 (28.0) |

| Clear cell | 5 (20.0) |

| Mucinous | 2 (8.0) |

| Site of recurrence | |

| Solitary | 19 (76.0) |

| Multiple | 6 (24.0) |

| Neoadjuvant therapy before secondary cytoreduction | 9 (36.0) |

| Secondary cytoreduction | |

| Optimal | 20 (80.0) |

| Suboptimal | 5 (20.0) |

| Surgical procedure associated with secondary debulking | |

| Wedge resection of liver | 1 |

| Colon resection | 8 |

| Small bowel resection | 2 |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 1 |

| Splenectomy | 2 |

| Adrenalectomy | 1 |

| Unilateral nephrectomy | 1 |

| Adjuvant therapy after secondary cytoreduction | |

| Yes | 23 (92.0) |

| No | 2(8.0) |

The median age at the time of recurrence was 52 years (range=31–78); 13 (52.0%) patients initially had stage III disease. At primary cytoreductive surgery, 20 patients (80.0%) had optimal, and five (20.0%) had suboptimal cytoreductive surgery. After primary surgery, all patients received platinum-based chemotherapy. The median DFI was 25.1 months (range=6.4–83.4). At the 5% significance level, only tumor grade was significantly (p<0.009) related to the disease-free interval [Table 2]. The median disease-free interval was 63.2, 16.7, and 22.4 months in disease grades one, two, and three, respectively. Patients with grade two and three tumors had shorter DFI compared to patients with grade one disease. Patients with optimal versus suboptimal primary cytoreductive surgery also appeared to have some relationship with the DFI [Table 3]; however, this was not statistically significant (p<0.348). This could be because the criteria for optimal cytoreduction varied in the study group.

Table 2. Median disease-free interval for all patients by prognostic factors.

| Variables | No. of events/No. of patients | Disease-free interval* (months) |

p- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 25/25 | 25.1 (12.8–35.2) | |

| Cancer stage | |||

| One | 7/7 | 33.7 (5.8–52.4) | 0.630 |

| Two | 3/3 | 23.0 (9.8–undefined) | |

| Three | 13/13 | 16.8 (10.7–33.6) | |

| Tumor grade | |||

| One | 5/5 | 63.2 (5.8–undefined) | 0.009 |

| Two | 10/10 | 16.7 (8.0–38.0) | |

| Three | 10/10 | 22.4 (5.4–26.6) | |

| Histopathology | |||

| Serous | 11/11 | 26.6 (10.7–46.2) | 0.705 |

| Endometroid | 7/7 | 12.8 (8.0–51.4) | |

| Clear cell | 5/5 | 25.1 (12.6–undefined) | |

| Mucinous | 2/2 | 5.8 (5.8–undefined) | |

| Primary cytoreduction | |||

| Optimal | 20/20 | 25.1 (9.8–46.2) | 0.313 |

| Suboptimal | 5/5 | 22.4 (10.7–undefined) |

**Median (95% CI).

Table 3. Median overall survival for all patients by prognostic factors.

| Variables | No. of events/No. of patients | Median disease-free interval (months)** |

p- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 11/25 | 33.1 (15.3–undefined) | |

| Stage | |||

| One | 2/7 | NR(1.3–undefined) | 0.024 |

| Two | 3/3 | 8.1 (8.0–undefined) | |

| Three | 5/13 | 33.1 (11.6–undefined) | |

| Tumor grade | |||

| One | 2/5 | NR (8.1–undefined) | 0.981 |

| Two | 5/10 | 33.1 (8.0–undefined) | |

| Three | 4/10 | 21.8 (1.3–undefined) | |

| Histopathology | |||

| Serous | 4/11 | 33.1 (9.7–undefined) | 0.089 |

| Endometroid | 2/7 | NR(8.0–undefined) | |

| Mucinous | 2/2 | 8.1 (8.1–undefined) | |

| Clear cell | 3/5 | 21.8 (1.3–undefined) | |

| Secondary cytoreduction | |||

| Optimal | 7/20 | NR (15.3–undefined) | 0.348 |

| Suboptimal | 4/5 | 21.8 (9.7–undefined) | |

| Disease-free interval | |||

| <12 months | 2/6 | NR (8.0–undefined) | 0.761 |

| 312 months | 9/19 | 30.6 (11.6–undefined) | |

| Response to secondary cytoreductive surgery | |||

| No* | 4/7 | 11.6 (1.3–undefined) | 0.007 |

| Yes | 7/18 | NR (18.5–undefined) |

**Median (95% CI); NR: Not reached.

*These patients had the progressive disease even after secondary surgery and chemotherapy.

Optimal secondary cytoreduction was achieved in 20 (80.0%) patients, five (20.0%) had suboptimal debulking. Of those five patients, three had nodal metastasis adherent to a major vessel, and the other two patients had a frozen pelvis with the disease extending up to the pelvic sidewall. Ten (40.0%) patients required bowel resection, but no end colostomy was performed. One (4.0%) patient had wedge resection of the liver, one (4.0%) had distal pancreatectomy, one (4.0%) had a unilateral nephrectomy, and one (4.0%) had adrenalectomy. There was no operative mortality. Following secondary cytoreductive surgery, 23 (85.2%) patients had adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy and two patients refused chemotherapy. Patients who did not respond to platinum-based chemotherapy were treated with second- and third-line chemotherapeutic agents.

The median follow-up duration for all patients was 38.9 months (95% CI, 17.8–72.4 months). Median overall survival was not reached for many groups, and 95% confidence intervals were not fully defined due to a small number of events (11 deaths out of 25 patients in total). Of the 25 patients, 12 (48.0%) developed a second recurrence and of these five patients underwent a third cytoreductive surgery, and seven patients received palliative chemotherapy.

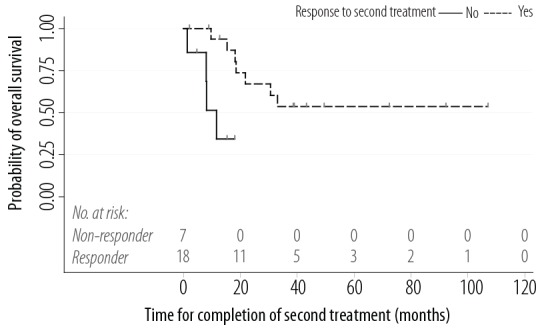

At the 5% significant level, only cancer stage was significantly related to overall survival. Stage two and three patients were shown to do have a worse overall survival than stage one cancer patients [Table 3]. From the Kaplan-Meier plots, secondary cytoreduction being optimal or suboptimal also appeared to have some relationship with overall survival, but was not statistically significant. Additionally, patients responding to secondary treatment (i.e. secondary cytoreductive surgery plus chemotherapy) were analyzed, and those patients who had progressive disease after completion of secondary treatment were termed non-responders. Non-responders had a significantly shorter OS compared to responders (p=0.002) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival for all patients by their response to secondary treatment

The DFS of those 18 patients who responded to secondary cytoreductive surgery was analyzed. Only histopathology was significantly related to disease-free survival at the 5% significance level [Table 4]. Of the histopathology types, patients with clear-cell carcinoma showed better survival (p=0.002). Overall, after a median follow-up time of 38.9 months, eight patients (32.0%) were alive with no evidence of disease, six (24.0%) were alive with disease, and eleven (44.0%) had died. Figure 1 shows the overall survival following secondary cytoreductive surgery. The overall one-, two- and three-year survival rate following secondary cytoreductive surgery was 78.1%, 56.1%, and 44.9%, respectively.

Table 4. Median disease-free survival by prognostic factors for patients who responded to secondary treatment.

| Variables | No. of events/No. of patients | Median disease-free survival (months)** | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 14/18 | 21.5 (8.2–30.6) | |

| Cancer stage | |||

| One | 4/6 | 16.6 (3.5–undefined) | 0.433 |

| Two | 1/1 | 12.3 (only one patient) | |

| Three | 7/9 | 21.5 (8.0–30.6) | |

| Tumor grade | |||

| One | 3/4 | 3.7 (3.5–undefined) | 0.268 |

| Two | 7/8 | 16.6 (8.0–24.9) | |

| Three | 4/6 | 52.9 (12.3–undefined) | |

| Histopathology | |||

| Serous | 6/8 | 22.0 (8.2–52.9) | <0.001 |

| Endometroid | 5/6 | 8.9 (3.7–undefined) | |

| Mucinous | 1/1 | 3.5 (only one patient) | |

| Clear cell | 2/3 | 87.0 (12.3–undefined) | |

| Secondary cytoreduction | |||

| Optimal | 10/13 | 22.0 (3.7–52.9) | 0.803 |

| Sub-optimal | 4/5 | 12.3 (8.9–undefined) | |

| Disease-free interval (months) | |||

| <12 | 3/4 | 22.0 (3.5–undefined) | 0.727 |

| ≥12 | 11/14 | 16.6 (8.2–52.9) |

**Median (95% CI).

Univariate analysis was performed on various clinical variables such as DFI (fewer than vs. more than 12 months), disease stage, tumor grade, and optimal versus suboptimal surgery. There was no significant difference in any of these variables, but those patients who responded to secondary cytoreductive surgery had a longer survival period than not responders.

Discussion

The role of primary cytoreductive surgery is well established in the management of epithelial ovarian cancer. Numerous investigators have documented improved survival after secondary cytoreductive surgery, but still lack evidence-based protocols for managing such patients. This is partly because most of the literature on this subject are non-randomized, retrospective studies. As these recurrent tumors develop resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy, and due to their heterogeneous behavior, the role of aggressive secondary cytoreductive surgery has always been questioned. Factors that affect survival following secondary cytoreductive surgery are disease-free interval following primary cytoreductive surgery and volume of residual disease following secondary cytoreductive surgery. Several studies, including ours, showed that the volume of residual disease after secondary cytoreduction had some effect on OS. We looked into the studies published on this subject over the last three decades. Since these studies were published between 1983 to 2012, the criteria for optimal cytoreduction varied from <2.5cm to no gross disease, we tabulated them according to the criteria used to see the rate of optimal secondary cytoreduction and their OS [Table 5]. During the period where the optimal cytoreduction was defined as <2.5 to >1.0cm, optimal cytoreduction was achieved in 37.5%–90.5% of cases and overall survival in these patients ranged from 10.0–45.8 months. When it was defined as less than <1.0cm optimal cytoreduction was achieved in 33.0%–100% of cases and the OS ranged from 11–48 months. With current definition of optimal cytoreduction being <0.25cm to no gross disease, optimal cytoreduction was achieved in 22.2%–100.0% of cases and OS in these patients was 22.5–60 months.

Table 5. Clinical series of cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer.

| Author | Study type | Publication year |

n (total) |

Age (median) |

Median overall survival (months) |

Disease-free interval (months) |

Optimal criteria (cm) |

Optimal cytoreduction (%) |

Complete cytoreduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berek et al9 | A | 1983 | 32 | 54.5 | 10 | 6 | <1.5 | 37.5 | NA |

| Morris et al10 | A | 1989 | 30 | 50 | 16.3 | 36 | <2.0 | 56.7 | 30.0 |

| Janicke et al11 | A | 1992 | 30 | 53 | 18 | 16 | <2.0 | 86.7 | 46.7 |

| Segna et al12 | A | 1993 | 100 | 55 | 16.6 | NA | <2.0 | 61.0 | NA |

| Eisenkop et al13 | B | 1995 | 36 | 60.6 | 43 | 22 | ≤1.0 | 91.7 | 83.3 |

| Vaccarello et al14 | A | 1995 | 57 | 57 | 18 | 20 | <0.5 | 36.8 | 17.5 |

| Landoni et al15 | A | 1998 | 38 | 51C (mean) | 29 | 22 | No gross | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Cormio et al16 | A | 1999 | 21 | 58 | 29 | 25 | <2.0 | 90.5 | 71.4 |

| Gadducci et al17 | A | 2000 | 30 | 58.5 | 21 | 17.5 | <2.0 | 83.3 | 56.7 |

| Zang et al18 | A | 2000 | 60 | 50 | 11 | 12 | ≤1.0 | 38.3 | NA |

| Chen et al19 | A | 2000 | 22 | 56.5 | 41 | 26 | <1.0 | 86.4 | 63.6 |

| Eisenkop et al20 | B | 2000 | 106 | 60.5 | 35.9 | 16.8 | No gross | 82.1 | 82.1 |

| Munkarah, et al21 | A | 2001 | 25 | 55 | 25.1 | 37.6 | ≤2.0 | 72 | 48 |

| Tay et al22 | A | 2002 | 46 | 50.3 | 22.5 | 26 | ≤1.0 | 71.7 | 41.3 |

| Bristow et al23 | A | 2002 | 21 | 46 | 56.2 | 15.7 | ≤1.0 | 71.4 | 61.9** |

| Yoon et al24 | B | 2003 | 24 | 47.5 | 62 | 36.5 | ≤1.0 | 100.0 | 87.5 |

| Zang et al25 | A | 2003 | 60 | 52 | 17 | NA | ≤1.0 | 38.3 | NA |

| Meredith et al26 | A | 2003 | 26 | 62 | 26.3 | 23.4 | ≤1.0 | 80.8 | 69.2 |

| Look et al27 | A | 2003 | 24 | 54 | 45.8 | NA | <2.5 | 87.5 | 20.8 |

| Loizzi et al28 | D | 2003 | 31 | 57 | 38 | 34 | <2.0 | 90.3 | NA |

| Leitao et al29 | A | 2004 | 26 | 55.5 | 33.4 | 13.4 | ≤0.5 | 73.1 | 53.8 |

| Zang et al30 | B | 2004 | 117 | 53 | 22 | 15.4 | ≤1.0 | 61.5 | 9.4 |

| Zanon et al31 | B | 2004 | 30 | 60 | 28.1 | NA | ≤0.25 | 76.7 | NA |

| Uzan et al32 | A | 2004 | 12 | 51 | 50 | 21 | No gross | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Gronlund et al33 | B | 2005 | 38 | 59C | 27.4E | 16.3 | No gross | 42.1 | 42.1 |

| Gungor et al34 | A | 2005 | 44 | 54.3 | 16 | 27.1 | <1.0 | 77.3 | NA |

| Yap et al35 | A | 2005 | 22 | 57.4 | 26 | 48.2 | <0.5 | 100.0 | NA |

| Onda et al36 | B | 2005 | 44 | 52 | 32 | 18.5 | <1.0 | 84.1 | 59.1 |

| Ayhan et al37 | A | 2006 | 64 | 50.6 | 18.6 | 15.5 | ≤1.0 | 82.8 | 43.8 |

| Matsumoto et al38 | A | 2006 | 23 | 55.7 | 41.7 | 22.5 | <2.0 | 43.4 | 30.4 |

| Manci et al39 | A | 2006 | 24 | 54 | 56 | 26 | ≤0.5 | 100.0 | 66.7 |

| Chi et al40 | A | 2006 | 153 | 56.5 | 41.7 | NA | ≤0.5 | 51.6 | 40.5 |

| Harter et al41 | B | 2006 | 267 | 60 | 29.2 | NA | ≤1.0 | 75.7 | 49.8 |

| Rufian et al42 | B | 2006 | 14 | 55 | 57 | NA | ≤1.0 | 85.0 | 52.0 |

| Helm et al43 | A | 2007 | 18 | 64 | 31 | 24.6 | ≤0.5 | 94.4 | 61.1 |

| Salani et al44 | A | 2007 | 55 | 57.7 | 48 | 26 | ≤1.0 | 89.1 | 74.5 |

| Santillan et al45 | A | 2007 | 25 | 59 | 37 | 16 | ≤1.0 | 100.0 | 96.0 |

| Benedetti Panici et al46 | B | 2007 | 40 | 51 | 60C | 14 | No gross | 72.5 | 72.5 |

| Benedetti Panici et al47 | B | 2007 | 47 | 52 | 49 | 15 | ≤1.0 | 87.2 | 78.7 |

| Cotte et al48 | B | 2007 | 81 | 54.3 | 28.4 | NA | ≤0.5 | 80.2 | 55.6 |

| Tebes et al49 | A | 2007 | 85 | 61 (mean) | 30 | 39 (mean) | <1.0 | 86 | NA |

| Fotiou et al50 | A | 2009 | 21 | 50 | 47 | 21 | ≤1.0 | 90.5 | 81 |

| Bae et al51 | A | 2009 | 54 | 54 | 42 | 24 | ≤0.5 | 87 | 59.3 |

| Cheng et al52 | A | 2009 | 21 | 53 | 27 | 14 | ≤1.0 | 33 | NA |

| Bristow et al53 | A | 2009 | 56 | 56 | 38.4 | NA | ≤1.0 | 92.9 | 85.7 |

| Fagotti et al54 | B | 2009 | 25 | 52 | C | 25 | <0.25 | NA | 92 |

| Harter et al55 | A | 2009 | 250 | 60 | 29.5 | NA | ≤1.0 | NA | 50 |

| Park et al56 | A | 2010 | 67 | 20 | 55.2 | ||||

| Tian et al57 | A | 2010 | 125 | 51 | 31.7 | 16.1 | ≤1.0 | 78.9 | 41.5 |

| Sehouli et al58 | B | 2010 | 240 | 57 | 29 | NA | ≤1.0 | 77.9 | 53.8 |

| Woelber et al59 | A | 2010 | 48 | 60 | 26 | 18 | <1.0 | 47.9 | 33.3 |

| Schorge et al1 | A | 2010 | 40 | 55.4 | 54 | 28 | <0.5 | 80 | 55 |

| Fagotti et al60 | B | 2011 | 41 | 52.6 | 38 | 19 | <0.25 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Frederick et al61 | A | 2011 | 62 | 52.7 | 28.2 | <1.0 | 40.3 | 36 | |

| Burton et al62 | A | 2011 | 20 | 59 | 22.5 | 18 | No gross | NA | 55 |

| Königsrainer et al63 | A | 2011 | 31 | 60 | 1150 days | 762 days | No gross | 90.3 | 65 |

| Classe et al64 | A | 2011 | 35 | 58.5 | 35 | 40 | <1.0 | 60 | 34.3 |

| Ceelen et al65 | B | 2012 | 42 | 52 | 37 | 3 | No gross | NA | 50 |

NA:data not available; A: retrospective review; B: prospective, non-randomized; C: median not yet reached; D: retrospective case-control; E: personal communication.

Various authors have shown that one important factor to have a significant influence on OS following secondary cytoreduction was the DFI (recurrence-free interval): a longer DFI was associated with more prolonged survival.3,17,18,22,66 However, some studies have shown that DFI was not a significant variable.4,8,9,44,49 In our study, the univariate analysis did not reveal any factors that affected the duration of OS. Our analysis was inherently limited by the potential for selection bias as, being a retrospective study, it covered a time during which concepts of optimal cytoreductive surgery and available adjuvant therapies evolved. This could have influenced the prognostic impact of individual variables on survival.

Conclusion

Our experience confirms that in a selected group of patients secondary cytoreduction improves survival of patients with ovarian cancer whose disease recurs at least six months after the primary treatment. Whether this is due to the surgical procedure itself or tumor biology remains unclear. There is urgent need for a large multi-institutional prospective randomized trial to analyze various variables and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study.

References

- 1.Schorge Epithelial Ovarian Cancer JO. Schorge, J.I. Schaffer, L.M. Holverson, B.L. Hoffman, K.D. Bradshaw, F.G. Cunningham (Eds.), Williams’ Gynecology (1st edn.), McGraw-Hill, New York (2008), p. 716. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong DK. Relapsed ovarian cancer: challenges and management strategies for a chronic disease. Oncologist 2002;7(Suppl 5):20-28. 10.1634/theoncologist.7-suppl_5-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jänicke F, Hölscher M, Kuhn W, von Hugo R, Pache L, Siewert JR, et al. Radical surgical procedure improves survival time in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer 1992. Oct;70(8):2129-2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segna RA, Dottino PR, Mandeli JP, Konsker K, Cohen CJ, Cohen CJ. Secondary cytoreduction for ovarian cancer following cisplatin therapy. J Clin Oncol 1993. Mar;11(3):434-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaccarello L, Rubin SC, Vlamis V, Wong G, Jones WB, Lewis JL, et al. Cytoreductive surgery in ovarian carcinoma patients with a documented previously complete surgical response. Gynecol Oncol 1995. Apr;57(1):61-65. 10.1006/gyno.1995.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman RL. Making of a Phase III Study in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: The Odyssey of GOG 213. Clinical Ovarian Cancer 2008. Jun;1(1):78-80 . 10.3816/COC.2008.n.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bristow RE, Puri I, Chi DS. Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2009. Jan;112(1):265-274. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi DS, Eisenhauer EL, Zivanovic O, Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Levine DA, et al. Improved progression-free and overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer as a result of a change in surgical paradigm. Gynecol Oncol 2009. Jul;114(1):26-31. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berek JS, Hacker NF, Lagasse LD, Nieberg RK, Elashoff RM. Survival of patients following secondary cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1983. Feb;61(2):189-193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris M, Gershenson DM, Wharton JT, Copeland LJ, Edwards CL, Stringer CA. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1989. Sep;34(3):334-338. 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jänicke F, Hölscher M, Kuhn W, von Hugo R, Pache L, Siewert JR, et al. Radical surgical procedure improves survival time in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer 1992. Oct;70(8):2129-2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segna RA, Dottino PR, Mandeli JP, Konsker K, Cohen CJ. Secondary cytoreduction for ovarian cancer following cisplatin therapy. J Clin Oncol 1993. Mar;11(3):434-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenkop SM, Friedman RL, Wang HJ. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer. A prospective study. Cancer 1995. Nov;76(9):1606-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaccarello L, Rubin SC, Vlamis V, Wong G, Jones WB, Lewis JL, et al. Cytoreductive surgery in ovarian carcinoma patients with a documented previously complete surgical response. Gynecol Oncol 1995. Apr;57(1):61-65. 10.1006/gyno.1995.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landoni F, Pellegrino A, Cormio G, Milani R, Maggioni A, Mangioni C. Platin-based chemotherapy and salvage surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer following negative second-look laparotomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1998. Feb;77(2):233-237. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1998.770220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cormio G, di Vagno G, Cazzolla A, Bettocchi S, di Gesu G, Loverro G, et al. Surgical treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer: report of 21 cases and a review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999. Oct;86(2):185-188. 10.1016/S0301-2115(99)00067-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gadducci A, Iacconi P, Cosio S, Fanucchi A, Cristofani R, Riccardo Genazzani A. Complete salvage surgical cytoreduction improves further survival of patients with late recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2000. Dec;79(3):344-349. 10.1006/gyno.2000.5992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zang RY, Zhang ZY, Li ZT, Chen J, Tang MQ, Liu Q, et al. Effect of cytoreductive surgery on survival of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol 2000. Sep;75(1):24-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen LM, Leuchter RS, Lagasse LD, Karlan BY. Splenectomy and surgical cytoreduction for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2000. Jun;77(3):362-368. 10.1006/gyno.2000.5800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenkop SM, Friedman RL, Spirtos NM. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in the treatment of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 2000. Jan;88(1):144-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munkarah A, Levenback C, Wolf JK, Bodurka-Bevers D, Tortolero-Luna G, Morris RT, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for localized intra-abdominal recurrences in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2001. May;81(2):237-241. 10.1006/gyno.2001.6143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tay EH, Grant PT, Gebski V, Hacker NF. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2002. Jun;99(6):1008-1013. 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)01977-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bristow RE, Gossett DR, Shook DR, Zahurak ML, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, et al. Recurrent micropapillary serous ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 2002. Aug;95(4):791-800. 10.1002/cncr.10789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon SS, Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Barakat RR, Blumgart LH, et al. Resection of recurrent ovarian or fallopian tube carcinoma involving the liver. Gynecol Oncol 2003. Nov;91(2):383-388. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zang RY, Li ZT, Zhang ZY, Cai SM. Surgery and salvage chemotherapy for Chinese women with recurrent advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a retrospective case-control study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2003. Jul-Aug;13(4):419-427. 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13315.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merideth MA, Cliby WA, Keeney GL, Lesnick TG, Nagorney DM, Podratz KC. Hepatic resection for metachronous metastases from ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2003. Apr;89(1):16-21. 10.1016/S0090-8258(03)00004-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Look M, Chang D, Sugarbaker PH. Long-term results of cytoreductive surgery for advanced and recurrent epithelial ovarian cancers and papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2003. Nov-Dec;13(6):764-770. 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2003.13319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loizzi V, Chan JK, Osann K, Cappuccini F, DiSaia PJ, Berman ML. Survival outcomes in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who were treated with chemoresistance assay-guided chemotherapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003. Nov;189(5):1301-1307. 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00629-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leitao MM, Jr, Kardos S, Barakat RR, Chi DS. Tertiary cytoreduction in patients with recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2004. Oct;95(1):181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zang RY, Li ZT, Tang J, Cheng X, Cai SM, Zhang ZY, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: who benefits? Cancer 2004. Mar;100(6):1152-1161. 10.1002/cncr.20106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zanon C, Clara R, Chiappino I, Bortolini M, Cornaglia S, Simone P, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia for recurrent peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. World J Surg 2004. Oct;28(10):1040-1045. 10.1007/s00268-004-7461-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uzan C, Morice P, Rey A, Pautier P, Camatte S, Lhommé C, et al. Outcomes after combined therapy including surgical resection in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer recurrence(s) exclusively in lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol 2004. Jul;11(7):658-664. 10.1245/ASO.2004.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gronlund B, Lundvall L, Christensen IJ, Knudsen JB, Høgdall C. Surgical cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian carcinoma in patients with complete response to paclitaxel-platinum. Eur J Surg Oncol 2005. Feb;31(1):67-73. 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Güngör M, Ortaç F, Arvas M, Kösebay D, Sönmezer M, Köse K. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2005. Apr;97(1):74-79. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yap OW, Kapp DS, Teng NN, Husain A. Intraoperative radiation therapy in recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005. Nov;63(4):1114-1121. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onda T, Yoshikawa H, Yasugi T, Yamada M, Matsumoto K, Taketani Y. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: proposal for patients selection. Br J Cancer 2005. Mar;92(6):1026-1032. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayhan A, Gultekin M, Taskiran C, Aksan G, Celik NY, Dursun P, et al. The role of secondary cytoreduction in the treatment of ovarian cancer: Hacettepe University experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006. Jan;194(1):49-56. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsumoto A, Higuchi T, Yura S, Mandai M, Kariya M, Takakura K, et al. Role of salvage cytoreductive surgery in the treatment of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer after platinum-based chemotherapy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2006. Dec;32(6):580-587. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2006.00460.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manci N, Bellati F, Muzii L, Calcagno M, Alon SA, Pernice M, et al. Splenectomy during secondary cytoreduction for ovarian cancer disease recurrence: surgical and survival data. Ann Surg Oncol 2006. Dec;13(12):1717-1723. 10.1245/s10434-006-9048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chi DS, McCaughty K, Diaz JP, Huh J, Schwabenbauer S, Hummer AJ, et al. Guidelines and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 2006. May;106(9):1933-1939. 10.1002/cncr.21845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harter P, du Bois A, Hahmann M, Hasenburg A, Burges A, Loibl S, et al. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Ovarian Committee. AGO Ovarian Cancer Study Group . Surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie (AGO) DESKTOP OVAR trial. Ann Surg Oncol 2006. Dec;13(12):1702-1710. 10.1245/s10434-006-9058-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rufián S, Muñoz-Casares FC, Briceño J, Díaz CJ, Rubio MJ, Ortega R, et al. Radical surgery-peritonectomy and intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in recurrent or primary ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol 2006. Sep;94(4):316-324. 10.1002/jso.20597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helm CW, Randall-Whitis L, Martin RS, III, Metzinger DS, Gordinier ME, Parker LP, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in conjunction with surgery for the treatment of recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2007. Apr;105(1):90-96. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salani R, Santillan A, Zahurak ML, Giuntoli RL, II, Gardner GJ, Armstrong DK, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for localized, recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: analysis of prognostic factors and survival outcome. Cancer 2007. Feb;109(4):685-691. 10.1002/cncr.22447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santillan A, Karam AK, Li AJ, Giuntoli R, II, Gardner GJ, Cass I, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for isolated nodal recurrence in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2007. Mar;104(3):686-690. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benedetti Panici P, De Vivo A, Bellati F, Manci N, Perniola G, Basile S, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007. Mar;14(3):1136-1142. 10.1245/s10434-006-9273-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benedetti Panici P, Perniola G, Angioli R, Zullo MA, Manci N, Palaia I, et al. Bulky lymph node resection in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: impact of surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2007. Nov-Dec;17(6):1245-1251. 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00929.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cotte E, Glehen O, Mohamed F, Lamy F, Falandry C, Golfier F, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemo-hyperthermia for chemo-resistant and recurrent advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: prospective study of 81 patients. World J Surg 2007. Sep;31(9):1813-1820. 10.1007/s00268-007-9146-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tebes SJ, Sayer RA, Palmer JM, Tebes CC, Martino MA, Hoffman MS. Cytoreductive surgery for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2007. Sep;106(3):482-487. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fotiou S, Aliki T, Petros Z, Ioanna S, Konstantinos V, Vasiliki M, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients presenting with isolated nodal recurrence of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2009. Aug;114(2):178-182. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bae J, Lim MC, Choi JH, Song YJ, Lee KS, Kang S, et al. Prognostic factors of secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol 2009. Jun;20(2):101-106. 10.3802/jgo.2009.20.2.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng X, Jiang R, Li ZT, Tang J, Cai SM, Zhang ZY, et al. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC). Eur J Surg Oncol 2009. Oct;35(10):1105-1108. 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bristow RE, Peiretti M, Gerardi M, Zanagnolo V, Ueda S, Diaz-Montes T, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery including rectosigmoid colectomy for recurrent ovarian cancer: operative technique and clinical outcome. Gynecol Oncol 2009. Aug;114(2):173-177. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fagotti A, Paris I, Grimolizzi F, Fanfani F, Vizzielli G, Naldini A, et al. Secondary cytoreduction plus oxaliplatin-based HIPEC in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer patients: a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol 2009. Jun;113(3):335-340. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harter P, Hahmann M, Lueck HJ, Poelcher M, Wimberger P, Ortmann O, et al. Surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer: role of peritoneal carcinomatosis: exploratory analysis of the DESKTOP I Trial about risk factors, surgical implications, and prognostic value of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol 2009. May;16(5):1324-1330. 10.1245/s10434-009-0357-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park JY, Eom JM, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery in the management of platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol 2010. Apr;101(5):418-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian WJ, Jiang R, Cheng X, Tang J, Xing Y, Zang RY. Surgery in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: benefits on Survival for patients with residual disease of 0.1-1 cm after secondary cytoreduction. J Surg Oncol 2010. Mar;101(3):244-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sehouli J, Richter R, Braicu EI, Bühling KJ, Bahra M, Neuhaus P, et al. Role of secondary cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer relapse: who will benefit? A systematic analysis of 240 consecutive patients. J Surg Oncol 2010. Nov;102(6):656-662. 10.1002/jso.21652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woelber L, Jung S, Eulenburg C, Mueller V, Schwarz J, Jaenicke F, et al. Perioperative morbidity and outcome of secondary cytoreduction for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010. Jun;36(6):583-588. 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fagotti A, Costantini B, Vizzielli G, Perelli F, Ercoli A, Gallotta V, et al. HIPEC in recurrent ovarian cancer patients: morbidity-related treatment and long-term analysis of clinical outcome. Gynecol Oncol 2011. Aug;122(2):221-225. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frederick PJ, Ramirez PT, McQuinn L, Milam MR, Weber DM, Coleman RL, et al. Preoperative factors predicting survival after secondary cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2011. Jul;21(5):831-836. 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821743f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burton E, Chase D, Yamamoto M, de Guzman J, Imagawa D, Berman ML. Surgical management of recurrent ovarian cancer: the advantage of collaborative surgical management and a multidisciplinary approach. Gynecol Oncol 2011. Jan;120(1):29-32. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Königsrainer I, Beckert S, Becker S, Zieker D, Fehm T, Grischke EM, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC in peritoneal recurrent ovarian cancer: experience and lessons learned. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011. Oct;396(7):1077-1081. 10.1007/s00423-011-0835-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Classe JM, Jaffre I, Frenel JS, Bordes V, Dejode M, Dravet F, et al. Prognostic factors for patients treated for a recurrent FIGO stage III ovarian cancer: a retrospective study of 108 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol 2011. Nov;37(11):971-977. 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.08.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ceelen WP, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Van Belle S, Denys H, Pattyn P. Cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion in women with heavily pretreated recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2012. Jul;19(7):2352-2359. 10.1245/s10434-009-0878-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scarabelli C, Gallo A, Carbone A. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2001. Dec;83(3):504-512. 10.1006/gyno.2001.6404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]