Introduction

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is a nearly universal finding in patients with end-stage renal disease. When left untreated, secondary hyperparathyroidism results in kidney stones, osteoporosis, and pathological fractures.1 These symptoms and the necessity of dialysis have serious implications on patient’s quality of life. Kidney transplantation remains the treatment of choice in renal failure and is reported to resolve many of the endocrine and metabolic imbalances of hyperparathyroidism.2 The current practice in the transplant community is to wait 12 months after transplant prior to considering parathyroidectomy.3 This is based on previous work which demonstrated that post-transplant hypercalcemia typically resolves within 1 year after successful renal transplantation.4 Accordingly, a watchful waiting approach is typically employed for asymptomatic patients with elevated parathyroid hormone levels in the year following transplantation.

Many parameters have been studied as possible risk factors for predicting persistent post-transplant hyperparathyroidism, including female gender, elevated pre-transplant parathyroid hormone (PTH) and hypercalcemia, 2, 5 but none have been prospectively validated. For patients with persistent or recurrent hyperparathyroidism post-transplant, the only curative treatment is parathyroidectomy, which has been shown to be safe and effective.2, 6, 7

The aim of this study is to examine the incidence of persistent hyperparathyroidism after renal transplantation in a contemporary cohort. We then sought to identify factors predictive of serum PTH normalization, and finally studied the impact of elevated serum PTH levels on overall graft as well as patient survival.

METHODS

The Division of Transplant Surgery at the University of Wisconsin prospectively maintains a database of all transplant cases since 1994. We examined solitary renal transplant patients between January 1, 2004 and June 30, 2012. For improved homogeneity of this cohort, we only included patients with a minimum of 24 months of graft survival, as well as a minimum of 24 months of follow-up. Our primary outcome of interest was the incidence of normalization of PTH levels after transplant. From all available serum PTH levels in the months following transplantation, patients were stratified into three groups: those who normalized serum PTH within the first year after transplant, those who normalized serum PTH between the first and second years after transplant, with the remaining patients having recurrent or persistently elevated serum PTH classified as having hyperparathyroidism. Normalization was defined as a PTH value less than 72 pg/mL, which is the upper limit of normal in our laboratory system.

We also sought to examine the impact of serum PTH normalization on overall renal allograft survival. As increasing transplant number negatively impacts graft survival, we then excluded patients with a history of previous transplantation and looked only at those receiving their first renal allograft. Allograft loss included resumption of dialysis, or patient death with or without a functional graft. Therefore, a patient survival analysis was conducted specifically examining serum PTH normalization and patient death.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed comparing the mean overall length of graft survival between groups based on timing of serum PTH normalization. Univariate comparison of means was performed using Student t test or Pearson Χ2 test, as appropriate. A multivariable logistic regression model was then constructed including all significant variables on univariate analysis, with results expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. A Kaplan-Meier log-rank survival analysis was then performed to determine the association between normalization of PTH and overall graft survival, as well as overall patient survival. Statistical significant was defined as p< 0.05.

RESULTS

Patients

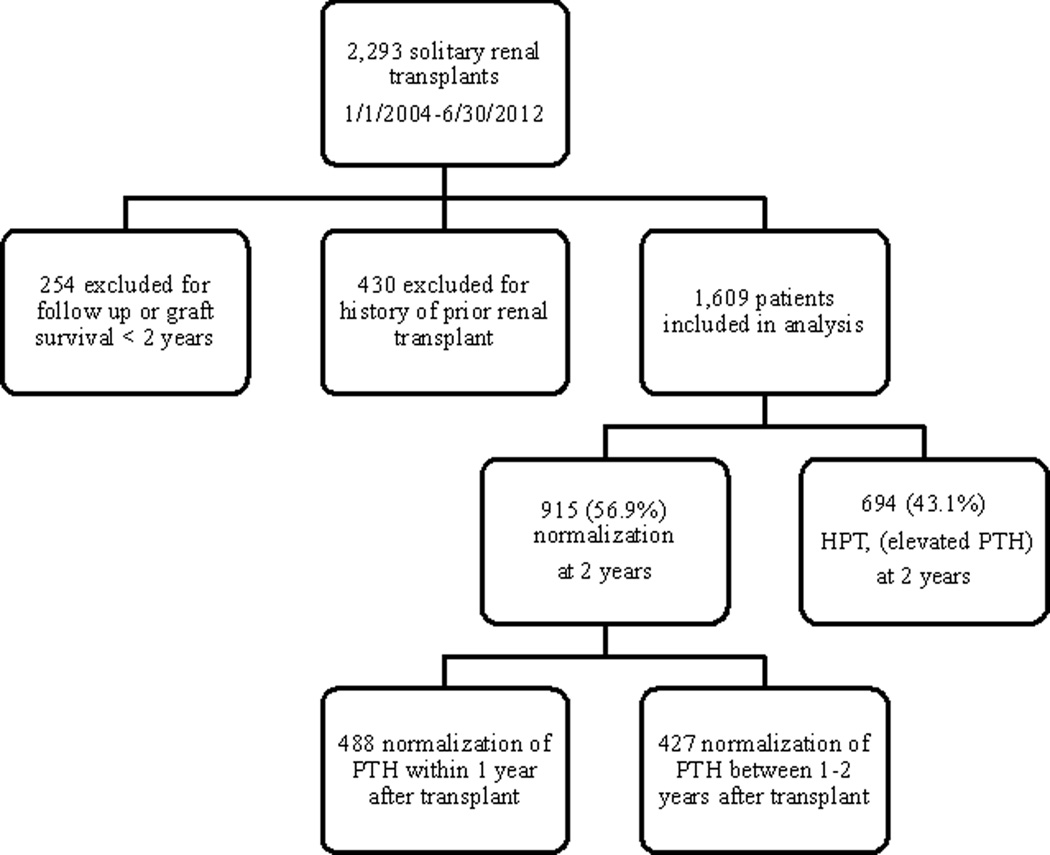

A total of 2,293 patients underwent solitary renal transplantation between January 1, 2004 and June 30, 2012. Of these, we excluded 254 patients for graft survival or follow-up time less than 24 months. We also excluded 430 patients with history of prior renal transplantation. This left 1,609 patients who met our inclusion criteria. We then examined all post-transplant serum PTH levels for resolution to the normal range. Nine hundred fifteen (56.9%) patients normalized serum PTH by 2 years post-transplant, and 694 (43.1%) patients developed hyperparathyroidism, or elevated serum PTH levels. (Figure 1) Of the 694 patients who did not achieve a normal serum PTH level by 2 years post-transplant, 558 (80.4%) were due to persistent disease, with the remaining 19.6% due to recurrent disease. The 915 patients who achieved normal serum PTH within the first two years of transplantation were further stratified into those who resolved within the first year (n=488, 30.3%), or between the first and second year (n=427, 26.6%). There was a slight male predominance in all three groups, and the majority of patients across groups were white. (Table 1)

Figure 1. Flowchart of patient selection.

PTH = parathyroid hormone, HPT = hyperparathyroidism, defined as an elevated serum PTH level

Table 1.

Patient demographics and characteristics

| PTH resolution by 1 year (N=488) |

PTH resolution by 2 years (N=427) |

Hyperparathyroid patients (N=694) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant (years) | 47.7 ± 0.77 | 51.6 ± 0.67 | 51.5 ± 0.51 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 277 (56.8%) | 242 (56.7%) | 436 (62.8%) |

| Female | 211 (43.2%) | 185 (43.3%) | 258 (37.2%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 396 (81.1%) | 334 (78.2%) | 475 (68.4%) |

| Non-White | 90 (18.4%) | 92 (21.5%) | 217 (31.3%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 ± 0.25 | 27.2 ± 0.24 | 28.8 ± 0.20 |

| Time on dialysis pre-transplant (months) | 13.2 ± 0.93 | 17.3 ± 1.09 | 24.8 ± 0.20 |

| Donor type | |||

| Deceased | 241 (49.4%) | 248 (58.1%) | 455 (65.6%) |

| Live | 247 (50.6%) | 179 (41.9%) | 239 (34.4%) |

| Delayed Graft Failure | 26 (5.3%) | 66 (15.5%) | 150 (21.6%) |

| Graft survival (years) | 7.33 [5.02–9.26] | 4.92 [3.36–6.69] | 5.13 [3.43–6.79] |

| Time on transplant wait-list* (months) | N=406 32.6 ± 1.78 |

N=387 33.6 ± 2.10 |

N=652 38.4 ± 1.54 |

Results presented as median [25th; 75th percentile], mean ± standard error, or n (%)

PTH = parathyroid hormone, BMI = body mass index

N provided for each group due to missing data

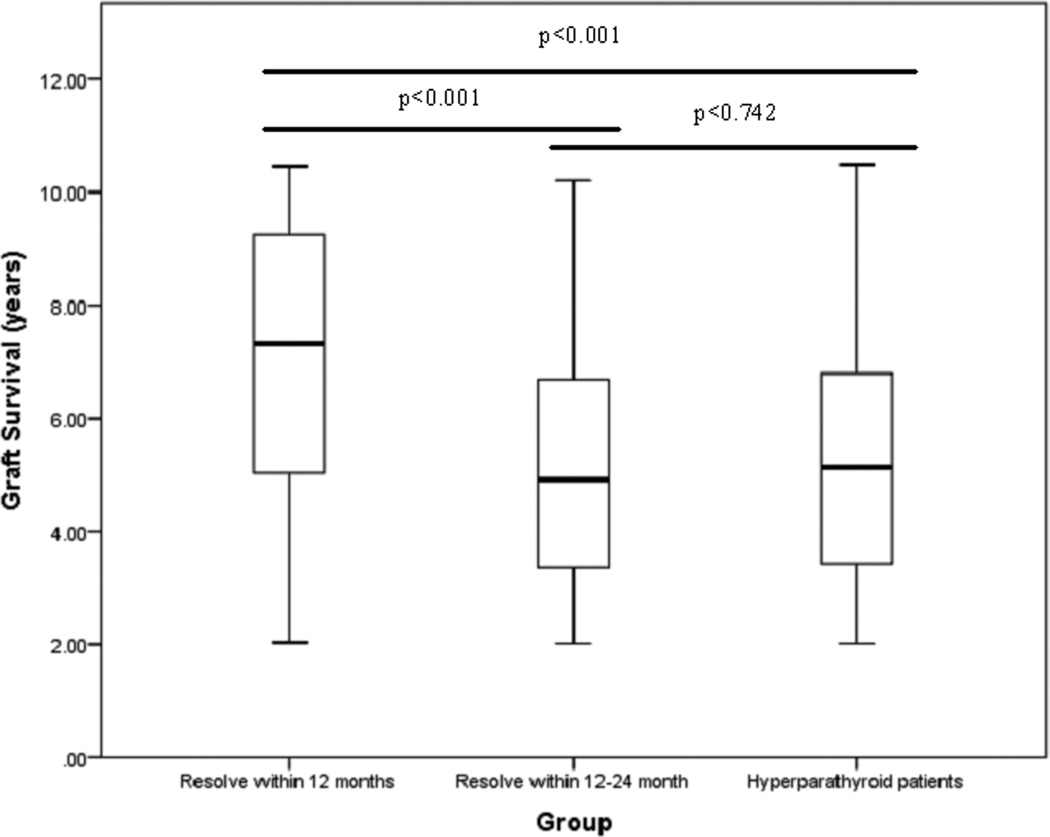

Patients who obtained normal serum PTH levels by the first year had a shorter mean time on dialysis, and a higher proportion underwent living donor transplantation. When calculating the mean time spent on the transplant waiting list, we excluded all patients that had a live donor since until recently recipients of live donors were not required to be listed. Patients who normalized their serum PTH values by 12 months had improved median graft survival (7.33 years, IQR 5.02–9.26) compared to those who did not normalize their serum PTH until 12–24 months (4.92 years, IQR 3.36–6.69), and those with hyperparathyroidism (5.13 years, IQR 3.43–6.79). ANOVA analysis of these three groups revealed a statistically significant difference on mean graft survival. Post-hoc analysis revealed that there was a difference between those that normalize their serum PTH within the first year and both other groups (p<0.001). There was no significant difference in mean graft survival between those who achieved normal PTH between 12–24 months, and hyperparathyroid patients (p=0.742). (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Median graft survival grouped by timing of parathyroid hormone resolution.

ANOVA boxplot of graft survival grouped by timing of parathyroid hormone resolution

Predictors of PTH normalization after renal transplantation

In order to determine patient factors that would be predictive of achieving a normal serum PTH at 2 years, the cohort was divided into two groups: those who achieved serum PTH normalization by 24 months post-transplant, and those who did not. (Table 2) Univariate analysis was initially performed between the two groups and variables with a p-value <0.05 were used to construct a multiple variable regression model. We found that obesity (p<0.001, OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.40–0.61), longer time spent on dialysis pre-transplantation (p<0.001, OR 0.986, 95% CI 0.980–0.991), and the development of delayed graft failure (DGF) defined as the need for acute dialysis within 7 days of transplantation (p<0.006, OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47–0.88) were predictive of not achieving normal serum PTH at 2 years. However, male gender (p=0.026, OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.03–1.57) and white race (p=0.003, OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.14–1.91) were predictive of achieving serum PTH normalization by 24 months. When adjusted, the kidney donor type (p=0.633), and patient age (p=0.053) were found to no longer be significant.

Table 2.

Factors predictive of normalization of PTH after renal transplantation

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTH Normalization* (N=915) |

No PTH Normalization (N=694) |

p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Sex (male) | 519 (56.7%) | 436 (62.8%) | .014 | 1.27 | 1.03–1.57 | .026 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 730 (79.8%) | 475 (68.4%) | <0.001 | 1.48 | 1.14–1.91 | .003 |

| Non-white | 182 (19.9%) | 217 (3 1.3%) | ||||

| Age at transplant (years) | 49.5 ± 0.52 | 51.5 ± 0.51 | 0.006 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | .053 |

| Obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 239 (26.1%) | 294 (42.4%) | <0.001 | 0.49 | 0.40–0.61 | <0.001 |

| Time on dialysis pre-transplant (months) | 15.1 ± 0.71 | 24.8 ± 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.986 | 0.980–0.991 | <0.001 |

| Donor type | ||||||

| Deceased | 489 (53.4%) | 455 (65.6%) | <0.001 | 1.06 | 0.84–1.35 | 0.633 |

| Live | 426 (46.6%) | 239 (34.4%) | ||||

| Presence of DGF | 92 (10.1%) | 150 (21.6%) | <0.001 | 0.65 | 0.47–0.88 | 0.006 |

Represented as mean ± standard error mean, or n (%)

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, PTH = parathyroid hormone, BMI = body mass index, DGF = delayed graft failure

Normalization defined as normal PTH value within 24 months of transplantation

Allograft and patient survival based on normalization of PTH

We then examined the effect of normalization of serum PTH by 24 months on overall graft, and patient survival. Graft loss was defined as resumption of dialysis, re-transplantation, or patient death with or without a functional allograft. Our mean follow up time was 6.03 ± 0.06 years. There were a total of 329 graft losses in our cohort. Of these, 148 (45%) of patients resumed dialysis, and 9 (2.7%) patients were re-transplanted. There were a total of 172 (52.3%) patient deaths, of which 168 (97.6%) died with a functioning graft. The majority of post-transplant mortality was attributed to an unknown cause (68 patients, 39.5%). Of the known causes of death, the three most frequently reported reasons were infection (38 patients, 22.1%), cardiovascular events including stroke (36 patients, 22.1%), and malignancy (29 patients, 16.3%).

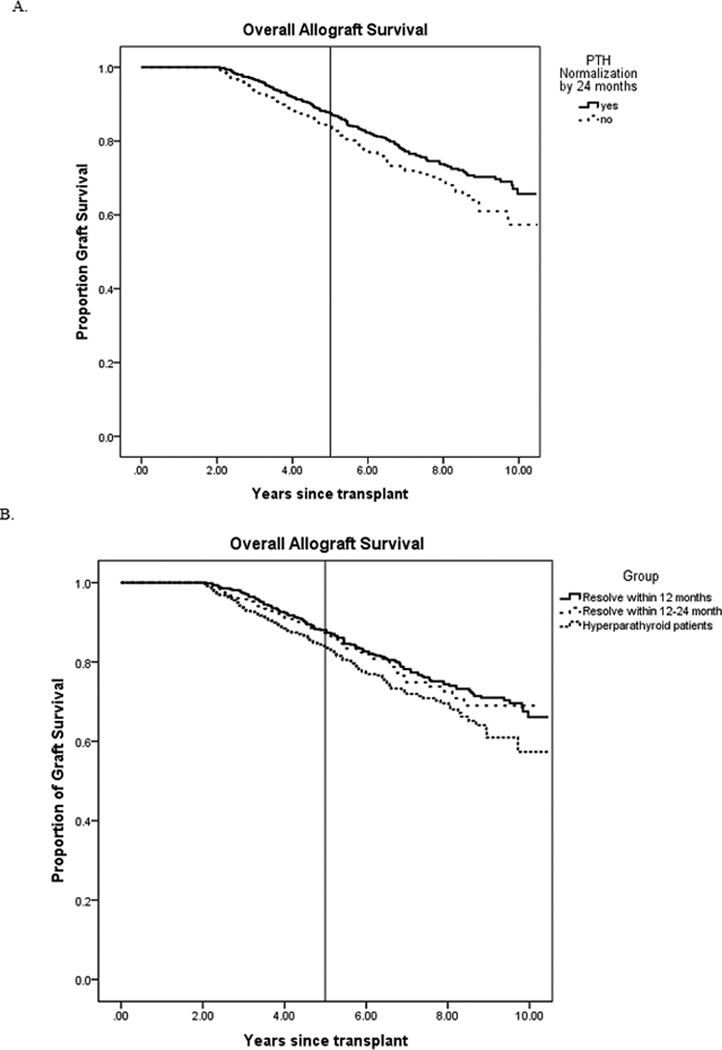

Normalization of serum PTH by 24 months was shown to have improved overall long-term allograft survival on Kaplan-Meier analysis (p=0.012). Five-year allograft survival was 88% in the normalization group compared to 84% in the non-normalization group. Further subdivided by timing of normalization, survival curves were drawn for those who resolved to normal serum PTH within 12 months, and those who resolved within 12–24 months. A similar trend was shown in this subgroup analysis, with patients who normalized within 12 months showing improved overall graft survival compared to other groups (p=0.038). Five- year allograft survival in those who resolved within 12 months, those who resolved within 12–24 months, and those with hyperparathyroidism were 88%, 87%, and 84%, respectively. (Figure 3) Paired comparisons revealed no difference between the resolution within 12 months and the resolution within 12–24 months groups.

Figure 3. Kaplan Meier allograft survival curves A. Grouped by normalization at 24 months post-transplant B. Grouped by timing of PTH normalization.

PTH = parathyroid hormone A. Long-term allograft survival by Kaplan-Meier estimate based on normalization of PTH. Reference line drawn at 5 years B. Long-term allograft survival by Kaplan-Meier estimate based on timing of PTH normalization. Reference line drawn at 5 years

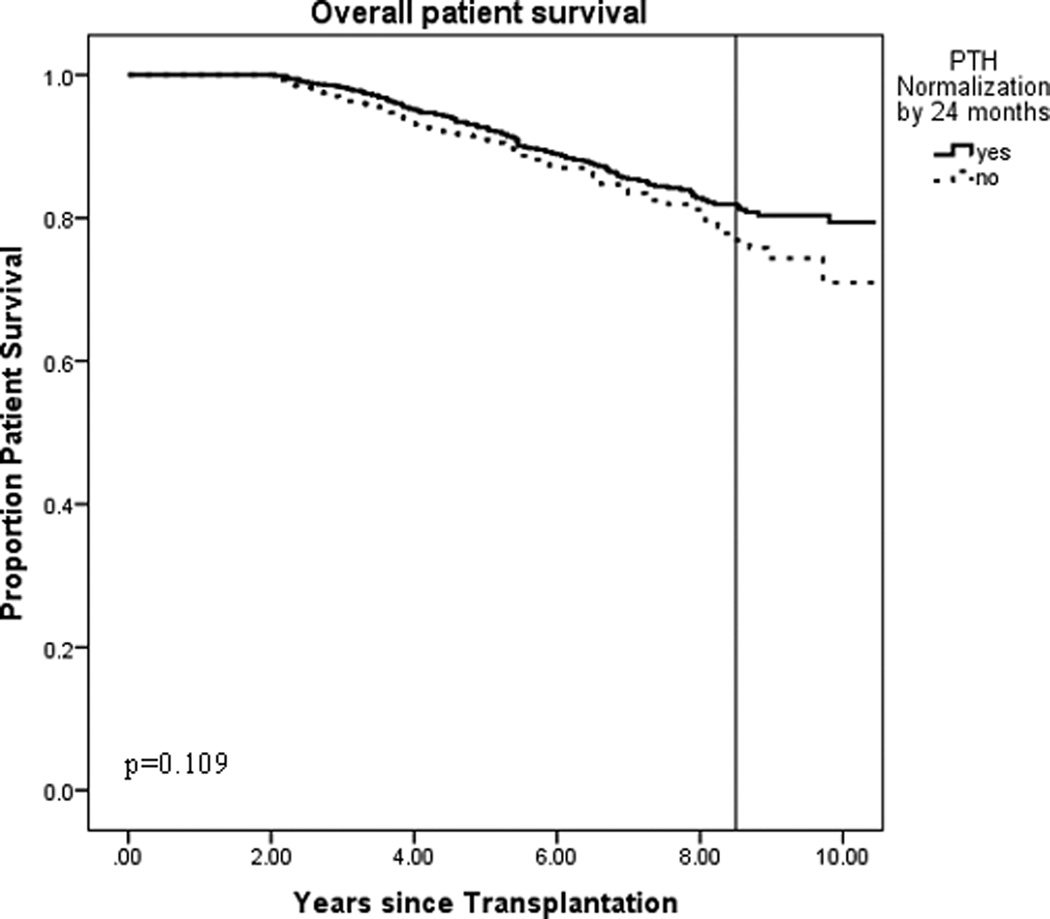

We then performed survival analysis specifically examining patient deaths to determine the impact of timing of serum PTH normalization on patient survival. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that patient survival in both groups trended very similarly with divergence around 8.5 years. A reference line drawn at that time point revealed the proportion of survival in the serum PTH normalization group was 0.819 compared to 0.778 in the no normalization group. Due to this late divergence, it is possible that a patient survival analysis beyond 10 years may demonstrate significant difference, but no differences were seen in our analysis (p=0.109).

DISCUSSION

Renal transplantation was initially reported to cure hyperparathyroidism in nearly 100% of patients.8, 9 Later studies have then noted that transplantation resolves secondary hyperparathyroidism in approximately 95% of patients10; however, these estimations were based on the assumption of coexisting hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia is often used as an endpoint for evaluation of hyperparathyroidism after transplantation1, 4, yet it is high levels of serum PTH rather than calcium that has been found to be associated with bone loss after renal transplantation.11 This study is unique in that it directly examines post-transplant serum PTH levels, and more specifically timing of PTH resolution, as a potential factor with impact on allograft survival. More recent work has also revealed that elevated levels of parathyroid hormone post-transplant occurs more commonly in the absence of hypercalcemia, and that the prevalence of elevation of serum PTH at both one and two years was stable at around 17%.12 Our study in a more contemporary cohort found that renal transplant cured hyperparathyroidism in only 30.3% of cases at one year, and 56.9% of cases at two years. A prospective study to identify the underlying mechanism by which parathyroid function is improved after renal transplantation found maximal recovery to occur between one and six months.13 We demonstrate that normalization of serum PTH, especially at an earlier time point after transplant, is associated with longer median and overall allograft survival. As the current practice pattern is to wait at least one year until intervention of an elevated serum PTH level, consideration should be made for earlier intervention after transplantation.

Many factors have been studied to determine associations with renal allograft failure including time spent on dialysis and donation source. Interestingly, the mean time spent on dialysis and percentage of live donors was directly related to timing of serum PTH resolution in this study. Patients who attained serum PTH resolution by 1 year had a higher percentage of living donors, and this likely contributes to the shortened interval of time spent on dialysis. Of the 665 living donor transplants, 410 (61.7%) were living related transplants, most often siblings followed by parents of the recipient. Regardless of whether the living donor kidney was from a related or unrelated donor, a living donor kidney has improved graft survival over a deceased donor.14 In addition, patients with potential living donors were not required to be placed on the transplant waiting list until July of 2014. Therefore while the time spent on the transplant waiting list is more similar amongst the three groups, due to missing data from live donor recipients, the time spent on dialysis prior to transplantation is likely a more accurate representation of actual waiting time. By combining the resolution by 12 months with the resolution by 12–24 months group to form the normalization by 24 months group for comparison, the mean time spent on dialysis was increased. As graft survival advantage of living donor transplantation diminishes with prolonged time on dialysis,15 this correlation may in part explain why donor type was no longer significant on multivariate analyses.

With improvements in immunosuppression regimens and care coordination, renal transplantation has made great strides with regard to short-term allograft survival. Nationally, the one year allograft survival in 2011 was 92.3% for deceased donors and 96.7% for living donors.16 Therefore, new attention has been brought to prevention of long-term allograft failure. In a single center retrospective study of 864 patients during a 13 year period undergoing primary renal transplantations, increased creatinine, delayed graft function, and age older than 45 were among the factors that predicted late graft failure.17 The rising incidence of obesity has also led to the examination of body mass index (BMI) as a predictor of long-term kidney transplant outcomes. A BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 was associated with an increased risk of delayed graft function, and therefore poorer graft and patient survival.18 In this modern cohort, we have found that normalization of PTH by 24 months is associated with improved overall allograft survival. Interestingly, delayed graft function and obesity were similarly significant predictive factors in PTH normalization within the first two years after transplantation. However, older recipient age was not a predictive factor. This is likely a reflection of an aging population and more careful selection of patients approved for transplantation. Our analysis also revealed white race as a positive predictive factor for PTH normalization. However, given the large proportion of white patients in our geographic area, this is not likely clinically significant.

Our study does have several limitations. We focused on post-transplant PTH values, but did not examine pre-transplant PTH or calcium levels. Tracking pre-transplant serum PTH values and evaluating the response after transplantation is important in further understanding the pathophysiology of secondary hyperparathyroidism, however this information was unavailable in our database. Query revealed that less than 20% of the patients in cohort had available pre-transplant serum PTH levels, and such values were obtained typically over a year prior to transplant date. By not examining calcium, we cannot truly classify our patients with tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Previous studies that have looked at patients with tertiary hyperparathyroidism relied heavily on hypercalcemia for basis of intervention.19 However determining indications for treatment was not the focus of our analysis. Since it is serum PTH that directly mediates the bone loss associated with hyperparathyroidism, we instead sought to determine the incidence of elevated serum PTH and its potential effect on graft survival. Resolution of serum PTH to the normal range is confounded by treatment interventions, either cinacalcet or parathyroid surgery. Spontaneous serum PTH resolution will most likely occur in the resolution by 12 month group with few interventions. Therefore treatments are occurring more commonly in the other two groups. To examine this further, we found no difference in the incidence of parathyroid surgery or cinacalcet prescriptions given to patients in the 12–24 month or hyperparathyroid groups. Additionally, only a small proportion our cohort (13%, or 200/1609) was given cinacalcet therefore unlikely affecting our primary endpoint. With the current practice patterns, renal transplant patients tend to have no intervention on elevated serum PTH levels until approximately 12 months after date of transplantation. We have demonstrated that achievement of normal PTH has a positive impact on overall allograft survival. Though we did not specifically examine renal function, among the 20% of our patients who suffered graft loss, over half died with intact renal function indicating generally adequate graft function. Although beyond the scope of this study, further work that explores a more exact timing of treatment of hyperparathyroidism after transplantation would certainly be useful. The contemporary nature of our cohort is an obvious strength, but also a limitation on follow-up time. As our patients were transplanted as recently as June of 2012, serum PTH normalization by 24 months would be captured but we are potentially underestimating the patients who develop recurrent disease. In addition, we lack 5-year overall allograft and patient survival data on these patients and therefore may also be underestimating the number of events taking place in these patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Hyperparathyroidism after renal transplantation continues to be an ongoing problem. We have shown the rate of serum PTH resolution is only 30.3% at 1 year, and 56.9% at 2 years after renal transplantation; lower than previously reported. In this contemporary cohort, we have shown normalization of serum PTH to within the normal range, especially by 1 year after transplant, is associated with improved overall renal allograft survival. The optimal timing of intervention of hyperparathyroidism in renal transplant patients is unknown, however, based on these findings consideration for earlier intervention is warranted.

Figure 4. Kaplan Meier estimate of overall patient survival based on normalization of PTH by 24 months post-transplant.

PTH = parathyroid hormone, Kaplan-Meier estimate of long-term patient survival based on normalization of PTH. Reference line drawn at divergence, at 8.5 years

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding:

Irene Lou is currently receiving grant support from NIH T32 CA090217-14

Footnotes

Presented at the American Surgical Association, San Diego, CA April 2015

Conflicts of Interest

For the remaining authors, none are declared.

References

- 1.Torres A, Lorenzo V, Salido E. Calcium metabolism and skeletal problems after transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:551–558. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V132551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evenepoel P, Claes K, Kuypers DR, et al. Parathyroidectomy after successful kidney transplantation: a single centre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1730–1737. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid T, Müller P, Spelsberg F. Parathyroidectomy after renal transplantation: a retrospective analysis of long-term outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2393–2396. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.11.2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David DS, Sakai S, Brennan BL, et al. Hypercalcemia after renal transplantation. Long-term follow-up data. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:398–401. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197308232890804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres A, Rodríguez AP, Concepción MT, et al. Parathyroid function in long-term renal transplant patients: importance of pre-transplant PTH concentrations. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13(Suppl 3):94–97. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.suppl_3.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Triponez F, Kebebew E, Dosseh D, et al. Less-than-subtotal parathyroidectomy increases the risk of persistent/recurrent hyperparathyroidism after parathyroidectomy in tertiary hyperparathyroidism after renal transplantation. Surgery. 2006;140:990–997. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.039. discussion 997-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nichol PF, Starling JR, Mack E, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with tertiary hyperparathyroidism treated by resection of a single or double adenoma. Ann Surg. 2002;235:673–678. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200205000-00009. discussion 678-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfrey AC, Jenkins D, Groth CG, et al. Resolution of hyperparathyroidism, renal osteodystrophy and metastatic calcification after renal homotransplantation. N Engl J Med. 1968;279:1349–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196812192792501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson JW, Hattner RS, Hampers CL, et al. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic renal failure. Effects of renal homotransplantation. JAMA. 1971;215:478–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parfitt AM. The hyperparathyroidism of chronic renal failure: a disorder of growth. Kidney Int. 1997;52:3–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heaf J, Tvedegaard E, Kanstrup IL, et al. Bone loss after renal transplantation: role of hyperparathyroidism, acidosis, cyclosporine and systemic disease. Clin Transplant. 2000;14:457–463. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2000.140503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evenepoel P, Claes K, Kuypers D, et al. Natural history of parathyroid function and calcium metabolism after kidney transplantation: a single-centre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:1281–1287. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonarek H, Merville P, Bonarek M, et al. Reduced parathyroid functional mass after successful kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 1999;56:642–649. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gjertson DW, Cecka JM. Living unrelated donor kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2000;58:491–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B. Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: a paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation. 2002;74:1377–1381. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Renal Data System. 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponticelli C, Villa M, Cesana B, et al. Risk factors for late kidney allograft failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1848–1854. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang SH, Coates PT, McDonald SP. Effects of body mass index at transplant on outcomes of kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:981–987. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000285290.77406.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitt SC, Sippel RS, Chen H. Secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism, state of the art surgical management. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:1227–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]