Abstract

Objective: To assess the integration of a smoking cessation intervention into routine tuberculosis (TB) services.

Method: Consecutive TB patients registered from 1 March to 31 August 2010 were enrolled in an intervention for self-reported smoking to promote tobacco cessation during treatment for TB. Information on the harmful health effects of tobacco smoke and smoking and TB were provided to TB patients who self-reported as current smokers. Smoking status was reassessed at every follow-up visit during anti-tuberculosis treatment with reinforced health messages and advice to quit.

Results: Of 800 TB patients enrolled, 572 (71.5%) were male and 244 (30.5%) were current smokers. Females were more likely to be non-smokers (100% vs. 35.8%, P < 0.001). Of the 244 current smokers, 144 (59.0%) started smoking at <20 years, 197 (80.7%) consumed ⩾20 cigarettes per day, 211 (86.5%) had perceived smoking dependence and 199 (81.6%) had made no attempt to quit before the diagnosis of TB. Of the 244 current smokers, 234 (95.9%) were willing to quit, and 156 (66.7%) reported abstinence at month 6. Challenges to implementing smoking cessation intervention were identified.

Conclusion: The majority of current smokers among TB patients were willing to quit and remained abstinent at the end of anti-tuberculosis treatment. This intervention should be scaled up nationwide.

Keywords: smoking, cessation, tuberculosis, China

Abstract

Objectif : Evaluer la possibilité d'intégrer une intervention d'arrêt du tabac dans les services de routine de la tuberculose (TB).

Méthode : Les patients tuberculeux consécutifs inscrits entre le 1e mars et le 31 août 2010 ont été enrôlés dans une intervention visant à promouvoir l'arrêt du tabac chez ceux qui disaient fumer pendant le traitement de leur TB. Des informations sur les effets sanitaires dangereux de la fumée de tabac et sur le fait de fumer en étant tuberculeux ont été fournies aux patients qui se sont dit fumeurs actuels. Le statut en matière de tabac a été réévalué à chaque visite de suivi pendant le traitement antituberculeux avec des messages sanitaires renforcés et des conseils visant à l'arrêt.

Résultats : Sur 800 patients TB enrôlés, 572 (71,5%) étaient des hommes et 244 (30,5%) étaient des fumeurs actuels. Les femmes étaient plus souvent non fumeuses (100% contre 35,8% ; P < 0,001). Des 244 fumeurs actuels, 144 (59,0%) avaient commencé à fumer avant 20 ans, 197 (80,7%) consommaient ⩾20 cigarettes par jour, 211 (86,5%) étaient conscients de leur dépendance au tabac et 199 (81,6%) n'avaient jamais essayé d'arrêter avant le diagnostic de TB. Des 244 fumeurs actuels, 234 (95,9%) voulaient arrêter et 156 (66,7%) ont déclaré être toujours abstinents à 6 mois. Les défis à la mise en œuvre d'une intervention d'arrêt du tabac ont été identifiés.

Conclusion : La majorité des fumeurs actuels parmi les patients TB voulaient arrêter et sont restés abstinents à la fin du traitement antituberculeux. Cette intervention devrait être étendue au pays tout entier.

Abstract

Objetivo: Evaluar la utilidad de la integración de las intervenciones de promoción del abandono del tabaquismo en los servicios ordinarios de atención de la tuberculosis (TB).

Métodos: Se inscribieron de manera consecutiva los pacientes con diagnóstico de TB y tabaquismo actual del 1° de marzo al 31 de agosto del 2010 en una intervención cuyo objeto era a promover el abandono del hábito tabáquico durante el tratamiento antituberculoso. Se suministró información acerca de los efectos deletéreos del humo del tabaco sobre la salud y de la asociación del tabaquismo y la TB a los pacientes que autorrefirieron un tabaquismo actual. En cada consulta de seguimiento durante el tratamiento se evaluó de nuevo la situación frente al tabaco, se reforzaron los mensajes sobre la salud y se reiteró el consejo de abandonar el hábito.

Resultados: De los 800 pacientes con TB inscritos, 572 fueron de sexo masculino (71,5%) y 244 eran fumadores actuales (30,5%). Las mujeres fueron con mayor frecuencia no fumadoras (100% contra 35,8%; P < 0,001). De los 244 fumadores actuales, 144 habían comenzado a fumar antes de los 20 años de edad (59,0%), 197 consumían ⩾20 cigarrillos por día (80,7%), 211 habían percibido la dependencia al tabaquismo (86,5%) y 199 nunca habían intentado abandonar el hábito antes del diagnóstico de TB (81,6%). De los 244 fumadores actuales, 234 estaban dispuestos a abandonar el tabaco (95,9%) y 156 notificaron abstinencia al sexto mes (66,7%). Se pusieron de manifiesto obstáculos a la aplicación de la intervención en favor del abandono del tabaquismo.

Conclusión: En su mayoría, los fumadores actuales entre los pacientes con diagnóstico reciente de TB estaban dispuestos a abandonar el tabaquismo y cumplieron con la abstinencia hasta el final del tratamiento antituberculoso. Se debería ampliar la aplicación de esta intervención a escala nacional.

China is one of the World Health Organization (WHO) defined 22 high tuberculosis (TB) burden countries, with an estimated 0.8–1.0 million TB cases per year, accounting for 11% of the global TB burden.1 There has been substantial progress in the fight against TB in China in the past two decades. In 1990, the prevalence of smear-positive pulmonary TB, at 170 per 100 000 population, had decreased to 59/100 000 by 2010.2 However, TB remains a major public health concern and, with a rate of 5.7% among new TB patients and 25.6% among previously treated patients, the prevalence of multidrug-resistant TB is relatively high.3

China also has a high burden of tobacco use and the largest number of smokers in the world.4 Available data suggest that the proportion of smokers among those aged ⩾15 years is 33.5%, 62.8% among males and 3.1% among females; 72.4% of the population is regularly exposed to second-hand smoke.5 Smoking has been reported to kill approximately 1 million persons annually in China.6

Several studies have highlighted a significant association between smoking and TB.7–11 TB patients who are smokers tend to take longer to access health care services,12 and are more likely to have recurrent TB than non-smokers.13,14 An association between smoking and drug-resistant TB and TB-related mortality has also been suggested.8,15,16 To address the dual burden of TB and smoking, the WHO and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) published a monograph on TB and tobacco control and called for the merging of efforts aimed at managing these two related global epidemics.17 The Union has published a guide on tobacco cessation interventions for TB patients,18 and organised a working group to pilot the guide. We report on the results of the smoking cessation intervention (SCI) for TB patients in China.

METHODS

Design

This was a prospective study of a pilot project implemented at two county TB dispensaries (public health TB clinics).

Setting

In 2009, The Union established a TB/Tobacco Working Group to pilot the SCI among TB patients. A meeting was held in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China, to review evidence on the association between tobacco smoke and TB and to discuss piloting of the SCI for TB patients in China. The Xingguo and Ningdu County TB dispensaries in Jiangxi Province were selected, in part because these are rural counties with a sufficiently large population (1.6 million). The annual number of registered TB patients at the TB dispensaries was approximately 1550. Xingguo County was one of the sampling sites in the 2010 national smoking prevalence survey; the proportion of males who smoked was 41.1%, while that of females was 0.

Study population

All consecutive TB patients registered from 1 March to 31 August 2010 were recruited into the study.

Smoking status

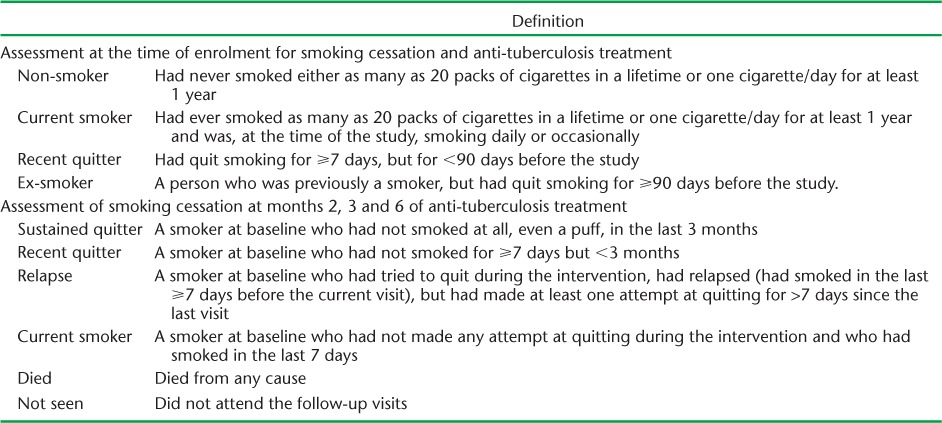

The patients' smoking status upon diagnosis of TB was assessed through a structured questionnaire administered by their doctors. The definitions used in the study are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Definition of non-smoker, smoker, quitter and ex-smoker at enrolment and outcome assessment

Cessation intervention

A one-day training course was conducted on the integration of the SCI into routine TB services. Four health care workers from Xingguo and Ningdu County TB dispensaries were trained to assess and monitor patients' smoking status and provide brief advice on smoking cessation. The health care workers then provided similar training for other health workers at their TB dispensaries. The SCI registers and the SCI card were adopted by participants for recording and reporting on their TB disease and smoking status.

General information on the harmful effects of tobacco smoke on health and specific information on smoking and TB was provided to current smokers, who were strongly advised to quit smoking. Current smokers were asked the following: 1) Do you want to stop? and 2) Do you intend to stop completely as of now? Anti-tuberculosis treatment was provided immediately, according to National TB Guidelines, regardless of smoking status and willingness to quit.19,20

TB patients who were willing to quit smoking immediately were enrolled into the cessation intervention. Information on the harmful effects of smoking on health and brief advice to quit were then reinforced during each visit to the TB dispensary. The smoking status of TB patients who smoked was re-assessed at the follow-up visits carried out at months 2, 3 and 6 of anti-tuberculosis treatment (Table 1).

Monitoring, recording and reporting

All enrolled patients were registered in the SCI register and assigned an SCI card. Supervision visits were carried out during the study period by Union and Jiangxi Provincial TB Institute staff. The supervision team assessed patient recruitment, provision of brief advice to recruited patients, maintenance of the SCI cards and the SCI registers and the challenges encountered.

Data analysis and statistics

Individual patient data were entered into a computer and cross-checked by Union and Jiangxi Provincial TB Institute staff. Data were analysed using STATA version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Categorical variables were analysed using Pearson's χ2 test. Multinomial logistic regression models were constructed to assess factors associated with smoking status at month 6 of anti-tuberculosis treatment, for which outcome was classified as follows: current smoker/relapse, quitter and died/not seen. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Jiangxi Provincial Institute of Tuberculosis Control and Prevention, Nanchang, China. As the information collected formed part of routine health services and patient information was handled only by those providing care to patients, no individual identifiers were provided to anyone who was not affiliated with the health service, and data were de-identified at the analysis stage, specific consent or review by an ethics committee was not considered necessary.

RESULTS

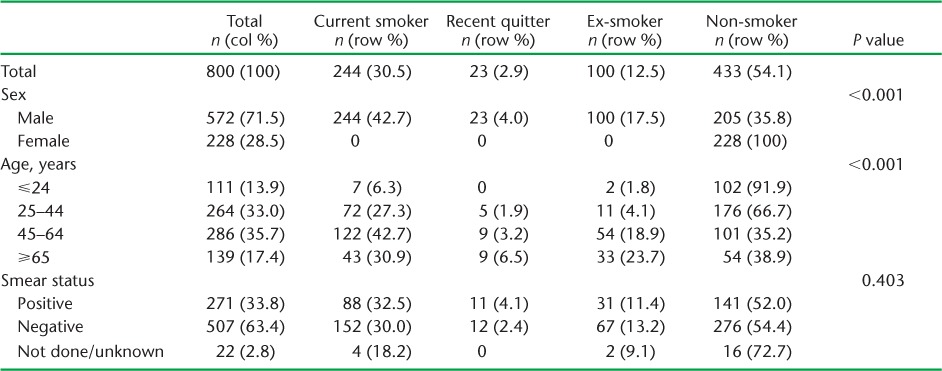

Of the 800 TB patients (age 14–92 years) diagnosed and registered during the 6-month study period, 572 (71.5%) were male, 550 (68.8%) were aged 25–64 years (mean age 46.2 ± 17.3) and 271 (33.8%) were smear-positive (Table 2). Of the 800 TB patients, 244 (30.5%) were current smokers, 23 (2.9%) were recent quitters, 100 (12.5%) were ex-smokers and 433 (54.1%) were non-smokers. Females were more likely to be non-smokers than males (100% vs. 35.8%, P < 0.001). The proportion of non-smokers was highest among those aged ⩽24 years (91.9%), followed by those aged 25–44 years (66.7%, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of registered tuberculosis patients, Xingguo and Ningdu Counties, China

Of the 244 current smokers, 144 (59.0%) began smoking under the age of 20, 197 (80.7%) consumed ⩾20 cigarettes per day, 211 (86.5%) perceived themselves as dependent on tobacco and 199 (81.6%) had not attempted to quit before being diagnosed with TB; 234 (95.9%) were willing to quit immediately. Age (P = 0.488), number of cigarettes consumed daily (P = 0.616), age at smoking initiation (P = 0.949), perceived dependence (P = 0.739) and previous quitting attempts (P = 0.125) were not significantly associated with willingness to quit smoking at baseline.

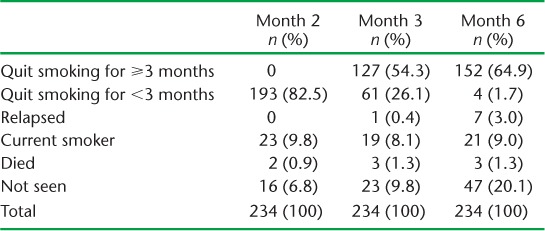

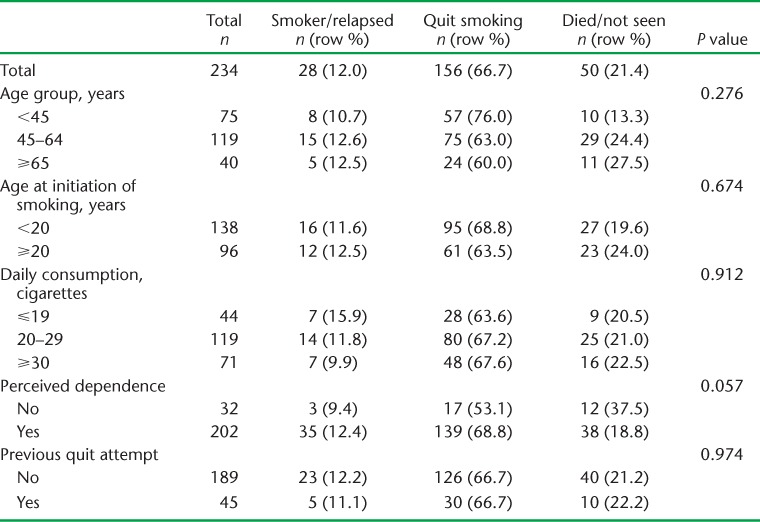

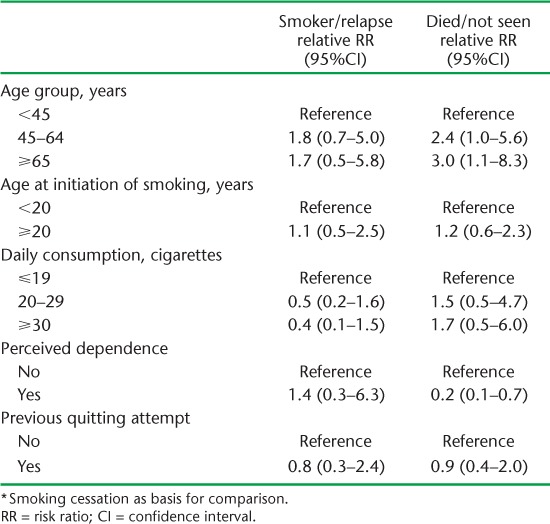

Of the 234 TB patients who were willing to quit smoking by participating in cessation services during anti-tuberculosis treatment, 193 (82.5%) attempted to quit at month 2; of these, 23 (9.8%) were smoking again at month 2. This number fell to 20 (8.5%; 19 current smokers and 1 relapse) at month 3, but increased to 28 (12%; 21 current smokers and 7 relapses) at month 6 (Table 3). Of the 234 patients, 152 (64.9%) had not smoked for ⩾3 months at month 6 of anti-tuberculosis treatment. Age (P = 0.276), age at smoking initiation (P = 0.674), number of cigarettes smoked daily (P = 0.912), perceived dependence (P = 0.057) and previous attempts at quitting (P = 0.974) were not significantly associated with smoking status at month 6 of anti-tuberculosis treatment, as determined through univariable analysis (Table 4). In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, no determinant was found to be significantly associated with current smoker/relapse as compared with quitting (Table 5).

TABLE 3.

Smoking status at months 2, 3 and 6 of 234 tuberculosis patients who were willing to quit at initiation of anti-tuberculosis treatment

TABLE 4.

Factors associated with smoking status at month 6 of anti-tuberculosis treatment

TABLE 5.

Multinomial logistic regression on factors associated with smoking status at month 6 of anti-tuberculosis treatment *

DISCUSSION

There is substantial evidence to support the association between TB and tobacco smoking.7,9,17,18 In our study, a high proportion of male TB patients had previously smoked; this indicated a strong need to integrate an SCI into the TB programme and clinical services.21–25

In our study, a substantial minority of TB patients had quit smoking prior to the tobacco cessation intervention. This was probably due to improved awareness about the harm caused by tobacco due to a health promotion programme that had been undertaken by the government;26 nevertheless, this requires further investigation. Although the proportion of male TB patients classified as current smokers was high, 95.9% of these were willing to quit, which indicated good opportunities for SCI. Prior to the study, a few doctors in Ningdu had advised patients to quit smoking during routine service provision; however, this was not done consistently. Researchers have reported that patients are inclined to follow physicians' advice to quit smoking if they have TB.26–28 We found that the majority of smokers had not attempted to quit smoking before their TB diagnosis, and that TB patients are indeed at a ‘teachable moment’ that renders them open to an SCI.

Our project achieved a 66.7% cessation rate at month 6 among current smokers who, at baseline, had indicated a willingness to quit, which is similar to reports of cessation intervention for tobacco use among TB patients in Sudan, Bangladesh and Indonesia.29–31 We assessed whether age, age at smoking initiation, daily consumption of tobacco, perceived dependence and previous quit attempts were associated with abstinence at month 6 of anti-tuberculosis treatment. None of the determinants were found to be significant, which suggests that abstinence is achievable regardless of such determinants.

Ng et al. reported that more than one third of quitters were starting to smoke again at the end of anti-tuberculosis treatment.22 We did not find a high frequency of smoking relapse, probably due to the merging of the intervention with intensive supervision throughout the course of anti-tuberculosis treatment.21 Our finding supported the findings of other researchers that patients who are ill are receptive to the advice of their health care providers.26,27

The following challenges in the piloting of the smoking cessation intervention among TB patients were identified: 1) some health care workers might have been reluctant to routinely advise patients on the harmful effects of tobacco and implement the cessation intervention due to busy clinical work, and 2) a few health care workers, particularly those who were smokers, did not acknowledge the SCI as an essential component of anti-tuberculosis treatment.

The study had several limitations. First, our findings may not be applicable to female smokers, as there were none in the study. Second, smoking status was based on self-report and was not confirmed by family members or through biochemical tests. A study using plasma cotinine as a reference standard has shown that self-reports are a reliable measure of smoking status;23 however, we do not know if there was any ‘social desirability bias’ and whether some patients were failing to report their true smoking behaviour. Third, 20.1% of the TB patients assigned to the SCI were not seen at month 6; their smoking status at the time was therefore unknown. This finding may raise questions about the reported high treatment success rate among TB patients in China, necessitating further investigation. Fourth, due to the lack of a control group, we could not determine the proportion of smokers who might have quit smoking without any intervention. Finally, we could not determine whether the intervention was implemented as intended.

This pilot project was conducted as part of routine TB services, without the use of any additional budget. The Ministry of Health, together with three other government agencies in China, issued a joint statement asking all health facilities to be smokefree by the end of 2011. Despite recommendations by the international community, smoking cessation has not yet been included in China's national TB control strategy. If SCIs were scaled up nationwide, a high cessation rate among a large number of smoking TB patients in China could substantially reduce the risk of TB recurrence.

CONCLUSION

The majority of TB patients who smoked were willing to quit, and those who had attempted quitting reported abstinence at follow-up, 6 months later. Our findings demonstrate the potential feasibility of the integration of a tobacco cessation intervention into routine TB services. It is important that countries with a dual burden of TB and tobacco use integrate SCIs into routine TB services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff at the two TB dispensaries who implemented the project and collected data for the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report, 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. WHO/HTM/TB/2014.08. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Zhang H, Ruan Y et al. Tuberculosis prevalence in China, 1990–2010: a longitudinal analysis of national survey data. Lancet. 2014;383:2057–2064. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao Y, Xu S, Wang L et al. National survey of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2161–2170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2008 (the MPOWER package) Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang G H. Global adult tobacco survey China 2010 country report. Beijing, China: China Center of Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu D F, Kelly T N, Wu X G et al. Mortality attributable to smoking in China. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:150–159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slama K, Chiang C-Y, Enarson D A et al. Tobacco and tuberculosis: a qualitative systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1049–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin H H, Ezzati M, Murray M. Tobacco smoke, indoor air pollution and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS MED. 2007;4:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed G W, Choi H, Lee S Y et al. Impact of diabetes and smoking on mortality in tuberculosis. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e58044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Den Boon S, van Lill S W, Borgdorff M W et al. The association between smoking and tuberculosis infection: a population survey in a high tuberculosis incidence area. Thorax. 2005;60:555–557. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang C-C, Tchetgen T E, Becerra M C et al. Cigarette smoking among tuberculosis patients increases risk of transmission to child contacts. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:1285–1291. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bam T S, Enarson D A, Hinderaker S G, Bam D S. Long delay in accessing treatment among current smokers with new sputum smear-positive tuberculosis in Nepal. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:822–827. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.d'Arc Lyra Batista J, de Fatima Pessoa Militao de Albuquerque M, de Alencar Ximenes R et al. Smoking increases the risk of relapse after successful tuberculosis treatment. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:841–851. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millet J P, Orcau A, de Olalla P G et al. Tuberculosis recurrence and its associated risk factors among successfully treated patients. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:799–804. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruddy M, Balabanova C, Graham C et al. Rates of drug resistance and risk factor analysis in civilian and prison patients with tuberculosis in Samara Region, Russia. Thorax. 2005;60:130–135. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.026922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang J, Liu B, Nasca P C et al. Smoking and risk of death due to pulmonary tuberculosis: a case-control comparison in 103 population centres in China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1530–1535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization & International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. A WHO/The Union monograph on TB and tobacco control—joining efforts to control two related global epidemics. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2007. WHO/HTM/TB/2007.390. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slama K, Chiang C-Y, Enarson D A. Tobacco cessation intervention for tuberculosis patients—a guide for low-income countries. Paris, France: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis: guideline for national programmes. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.420. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Health and China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline of national TB control program. Beijing, China: The Peking Union Medical College Publishing House; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sereno A B, Soares E C C, Lapa e Silva J R et al. Feasibility study of a smoking cessation intervention in Directly Observed Therapy Short-Course tuberculosis treatment clinics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Panam Publica. 2012;32:451–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng N, Padmawati R S, Prabandari Y S et al. Smoking behavior among former tuberculosis patients in Indonesia: intervention is needed. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunet L, Pai M, Davids V et al. High prevalence of smoking among patients with suspected tuberculosis in South Africa. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:139–146. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00137710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lönnroth K, Raviglione M. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: prospects for control. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:481–491. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health. China report on the health hazards of smoking. Beijing, China: People's Medical Publishing House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin S S, Xiao D, Cao M et al. Patient and doctor perspectives on incorporating smoking cessation into tuberculosis care in Beijing, China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:126–131. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Novotny T E. Smoking cessation and tuberculosis: connecting the DOTS. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awaisu A, Nik Mohamed M H, Noordin N M et al. The SCIDOTS project: evidence of benefits of an integrated tobacco cessation intervention in tuberculosis care on treatment outcomes. Substance Abuse Trea, Prev and Policy. 2011;6:26–39. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Sony A, Slama K, Salieh M et al. Feasibility of brief tobacco cessation advice for tuberculosis patients: a study from Sudan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddiquea B N, Islam M A, Bam T S et al. High quit rate among smokers with tuberculosis in a modified smoking cessation programme in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Public Health Action. 2013;3:243–246. doi: 10.5588/pha.13.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bam T S, Aditama T Y, Chiang C Y, Rubaeah R, Suhaemi A. Smoking cessation and smokefree environments for tuberculosis patients in Indonesia—a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:604. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1972-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]