Prosaposin directly interacts with progranulin and facilitates progranulin lysosomal trafficking via the trafficking receptors M6PR and LRP1, independent of the previously identified progranulin trafficking pathway mediated by sortilin.

Abstract

Mutations in the progranulin (PGRN) gene have been linked to two distinct neurodegenerative diseases, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL). Accumulating evidence suggests a critical role of PGRN in lysosomes. However, how PGRN is trafficked to lysosomes is still not clear. Here we report a novel pathway for lysosomal delivery of PGRN. We found that prosaposin (PSAP) interacts with PGRN and facilitates its lysosomal targeting in both biosynthetic and endocytic pathways via the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. PSAP deficiency in mice leads to severe PGRN trafficking defects and a drastic increase in serum PGRN levels. We further showed that this PSAP pathway is independent of, but complementary to, the previously identified PGRN lysosomal trafficking mediated by sortilin. Collectively, our results provide new understanding on PGRN trafficking and shed light on the molecular mechanisms behind FTLD and NCL caused by PGRN mutations.

Introduction

Proper lysosomal function is essential for cellular health and long-term neuronal survival (Nixon and Cataldo, 2006; Lee and Gao, 2008). Defects in lysosomal function cause a group of metabolic diseases known as lysosomal storage disorders, which are characterized by the accumulation of lysosomal cargoes and autophagic vacuoles and are often accompanied by severe neurodegenerative phenotypes (Bellettato and Scarpa, 2010). More recently, lysosomal dysfunction has also been implicated in adult-onset neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Nixon et al., 2008; Cook et al., 2012). Thus lysosomal dysfunction is closely linked to neurodegeneration.

Progranulin (PGRN) is an evolutionarily conserved, secreted glycoprotein of 7.5 granulin repeats that was recently implicated in several neurodegenerative diseases (Ahmed et al., 2007; Cenik et al., 2012). PGRN haploinsufficiency resulting from heterozygous mutations in the Granulin (GRN) gene is one of the major causes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) with ubiquitin-positive inclusions (FTLD-U; Baker et al., 2006; Cruts et al., 2006; Gass et al., 2006). It is believed that the neurotrophic and anti-inflammatory functions of PGRN and granulin peptides prevent neurodegeneration in the aging brain (Ahmed et al., 2007; Cenik et al., 2012). However, several recent studies have suggested a surprising role of PGRN in lysosomes (Ahmed et al., 2010; Belcastro et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2012; Götzl et al., 2014). First, homozygous PGRN mutant human patients exhibit neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL; Smith et al., 2012), a lysosomal storage disease characterized by the accumulation of autofluorescent storage material (lipofuscin), which is also seen in PGRN knockout mice (Ahmed et al., 2010). Second, PGRN is transcriptionally coregulated with several essential lysosomal genes (Belcastro et al., 2011). Finally, FTLD-U/GRN patients also exhibit typical pathological features of NCL patients (Götzl et al., 2014), suggesting FTLD and NCL caused by GRN mutations are pathologically linked and lysosomal dysfunction caused by PGRN mutations might serve as the common mechanism. Thus PGRN actions in lysosomes are essential for neuronal health. However, how PGRN gets delivered into lysosomes and its functions therein remain to be elucidated.

Previously, we have shown that sortilin, a member of the Vps10 family, mediates the delivery of PGRN into lysosomes (Hu et al., 2010). However, PGRN is still partially localized to lysosomes in sortilin-deficient neurons, suggesting an additional sortilin-independent mechanism for PGRN lysosomal trafficking. To understand these additional pathways and PGRN action in lysosomes, we performed a proteomic screen and uncovered a novel interaction between PGRN and prosaposin (PSAP), the precursor of saposin peptides (A, B, C, and D) that serve as activators of lysosomal sphingolipid metabolizing enzymes (O’Brien and Kishimoto, 1991; Qi and Grabowski, 2001; Matsuda et al., 2007). We demonstrate that PSAP helps target PGRN into lysosomes in both biosynthetic and endocytic pathways independent of sortilin, via the cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (M6PR) and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1).

Results

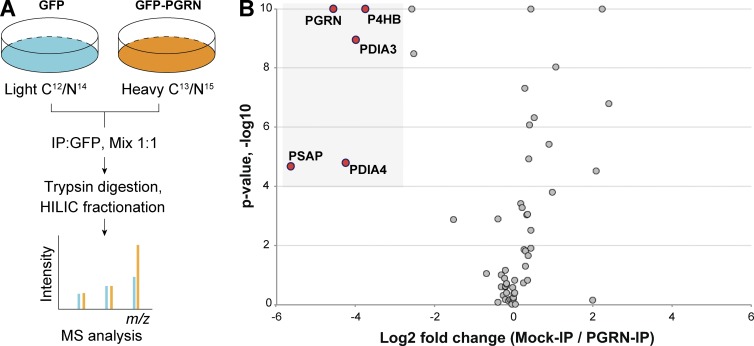

PGRN physically interacts with PSAP

To understand PGRN regulation and function, we searched for PGRN interactors using a stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) based proteomic screen (Fig. 1 A). In addition to several members of the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family, which have been shown to regulate PGRN folding and secretion (Almeida et al., 2011), we identified PSAP as the top hit from the screen (Fig. 1 B and Table S1). PSAP is a secreted glycoprotein and the precursor of saposin peptides that serve as activators of sphingolipid degradation in lysosomes (Matsuda et al., 2007). The PGRN–PSAP interaction was further verified by coimmunoprecipitation with overexpressed PGRN and PSAP in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2 A) and endogenous levels of PGRN and PSAP both in the medium and cell lysates of mouse fibroblasts (Fig. 2, B and C). Both PSAP and saposin peptides are detectable in the fibroblast lysates, but only full-length PSAP is present in the PGRN immunoprecipitate, suggesting saposins do not bind to PGRN under this immunoprecipitation condition (Fig. 2 B). Purified recombinant PGRN and PSAP (Fig. S1) strongly interact with each other at a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 2 D), indicating a direct physical interaction between PGRN and PSAP.

Figure 1.

Proteomic screen for PGRN interactors. (A) Schematic illustration of the SILAC experiment searching for PGRN interactors. (B) Volcano plot of SILAC hits. Top hits identified in the heavy fraction are highlighted. The complete list of proteins is summarized in Table S1.

Figure 2.

Physical interaction between PGRN and PSAP. (A) PGRN and PSAP interact when overexpressed in HEK293T cells. PSAP-V5 and FLAG-PGRN constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells as indicated. Lysates were prepared 2 d later and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies. (B and C) PSAP and PGRN interact with each other at endogenous levels in fibroblasts. Cell lysates (B) and conditioned medium (C) from wild-type (WT), PSAP−/− (PS−/−), and PGRN−/− (GRN−/−) fibroblasts were immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-PGRN antibodies. The presence of PGRN and PSAP in the immunoprecipitation was detected using sheep anti–mouse PGRN and rabbit anti–mouse PSAP antibodies, respectively. Asterisk indicates IgG bands. (D) Direct interaction between PGRN and PSAP. Purified recombinant his-PSAP and Flag-PGRN proteins of indicated amounts were mixed in 100 µl PBS + 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h before adding anti-FLAG beads. Beads were washed after a 2-h incubation. 0.2 µg of each purified protein was loaded as input. After SDS-PAGE, the gel was stained with Krypton dye to visualize proteins. The binding ratio of PGRN–PSAP was provided based on the densitometric evaluation of PGRN and PSAP band intensities. All the results shown are the representative pictures from at least three independent experiments.

PSAP facilitates lysosomal delivery of PGRN in the biosynthetic pathway

Because both PGRN and PSAP are lysosomal proteins, we hypothesized that they might regulate each other’s lysosomal trafficking. To test this, we evaluated the effect of PGRN or PSAP ablation on the other’s localization to lysosomes. In the wild-type fibroblast, PGRN and PSAP are colocalized within late endosomes/lysosomes, which are labeled by the lysosomal membrane protein LAMP1 (Fig. 3 A). Loss of PGRN has no obvious effect on PSAP lysosomal localization (Fig. S2). However, PSAP deficiency results in complete disruption of PGRN lysosomal localization in fibroblasts (Fig. 3, A and B). Loss of lysosomal PGRN signal is accompanied by increased secretion of PGRN to the extracellular space (Fig. 3, C and D) and increased colocalization of PGRN with the ER marker PDI (Fig. 3 E). To rule out a general defect of lysosomal targeting in PSAP−/− fibroblasts, we examined the localization of two other lysosomal proteins, cathepsin D and TMEM106B (Chen-Plotkin et al., 2012; Lang et al., 2012; Brady et al., 2013). Both cathepsin D and TMEM106B are lysosomally localized in PSAP−/− fibroblast (Fig. 4, A and B), confirming that PSAP deficiency does not cause a general defect in lysosomal trafficking. Mislocalization of PGRN is also observed in PSAP-deficient fibroblasts generated by the constitutive expression of shRNAs targeted to PSAP, as well as by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)–mediated genome editing (Fig. S3 A; Cong et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013). To further demonstrate that this defect is a result of direct loss of PSAP function, we infected PSAP−/− fibroblasts with lentivirus expressing mCherry-tagged PSAP. Lysosomal localization of PGRN is fully restored upon the expression of mCherry-PSAP in PSAP−/− fibroblast (Fig. S3 B). However, addition of recombinant PSAP protein to the medium to deliver PSAP through the endocytic pathway failed to rescue endogenous PGRN trafficking defects in PSAP−/− fibroblasts (Fig. S3 C), supporting that PSAP is required for the lysosomal trafficking of PGRN in the biosynthetic pathway in fibroblasts.

Figure 3.

PSAP is required for PGRN lysosomal targeting in fibroblasts. (A) Mislocalization of PGRN in PSAP−/− fibroblasts. Immunostaining for PGRN, LAMP1, and PSAP in fibroblasts derived from wild-type and PSAP−/− mice using sheep anti– mouse PGRN, rat anti–mouse LAMP1, and rabbit anti–mouse PSAP antibodies. PGRN mislocalization was observed in all the PSAP−/− fibroblasts examined. (B) Quantification of PGRN localization within LAMP1-positive vesicles in wild-type and PSAP−/− fibroblasts using ImageJ. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001, Student’s t test. (C) Increased PGRN secretion in PSAP−/− fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 h before the lysates and conditioned media (CM) were harvested. Proteins from the conditioned media were precipitated with TCA. (D) Quantification of experiments in C. PGRN levels are normalized to transferrin in the conditioned media and Gapdh in the cell lysates. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05, Student’s t test; N.S., no significance. (E) Immunostaining for PGRN, PDI, and cathepsin D in fibroblasts derived from wild-type and PSAP−/− mice. Representative images from three replicated experiments are shown Bars: (main) 20 µm; (inset) 5 μm.

Figure 4.

PSAP is not required for lysosomal localization of cathepsin D and TMEM106B in fibroblasts. (A) Immunostaining for PGRN, LAMP1, and cathepsin D in fibroblasts derived from wild-type and PSAP−/− mice. (B) Immunostaining for PGRN, LAMP1, and TMEM106B in fibroblasts derived from wild-type and PSAP−/− mice. Representative images from three replicated experiments are shown. Bars: (main) 20 µm; (inset) 5 μm.

PSAP facilitates lysosomal delivery of PGRN from the extracellular space

Receptor-mediated endocytosis from the extracellular space is another mechanism to deliver proteins to lysosomes. Because both PGRN and PSAP are secreted, we examined whether PSAP could also facilitate lysosomal delivery of PGRN from the extracellular space. Recombinant human PSAP and PGRN were purified from transfected HEK293T cells and added alone or in combination to fibroblasts isolated from PGRN−/− mice. Because the recombinant PGRN used in these experiments has a 6× histidine tag at its C terminus and the PGRN C terminus is required for its binding to sortilin (Zheng et al., 2011), these recombinant PGRN proteins are not capable of sortilin binding. After 12 h of incubation, purified PSAP alone is delivered to lysosomes labeled by the lysosomal marker LAMP1, whereas purified PGRN alone is not endocytosed (Fig. 5 A). However, the addition of PSAP with PGRN leads to lysosomal accumulation of both molecules (Fig. 5 A). Similar results were obtained with primary cortical neurons (Fig. S4). Western blot analysis confirmed the immunostaining results and showed that PGRN is only present in the cell lysate in the presence of PSAP (Fig. 5 B). Moreover, endocytosed PSAP is processed into saposin peptides, indicating lysosomal delivery of PSAP (Fig. 5 B). Consistent with this active endocytosis, a significant decrease in the extracellular levels of recombinant PGRN and PSAP proteins was observed (Fig. 5, B and C). Collectively, these experiments clearly demonstrate that PSAP facilitates lysosomal delivery of PGRN from the extracellular space in both fibroblasts and neurons.

Figure 5.

PSAP facilitates PGRN lysosomal targeting from the extracellular space. (A) PSAP facilitates PGRN lysosomal targeting from the extracellular space in fibroblasts. GRN−/− fibroblasts were treated with recombinant human his-PSAP and human FLAG-PGRN-his at a concentration of 5 µg/ml in serum-free media for 12 h as indicated. Fixed cells were stained with goat anti–human PGRN, rat anti–mouse LAMP1, and rabbit anti–human saposin B (PSAP) antibodies. Representative images from three replicated experiments are shown. Bars: (main) 20 µm; (inset) 5 μm. (B) Western blot analysis of PGRN and PSAP proteins in the uptake assay. GRN−/− fibroblasts were treated with PGRN and PSAP proteins as in A and the proteins in the lysate after 24-h uptake as well proteins in the medium before and after 24-h uptake are shown. Western blots were detected using goat anti–human PGRN and rabbit anti–human saposin B antibodies. For unknown reasons, PSAP signal is always stronger in the medium when PGRN is added together in the Western blot (although the same amount of PSAP protein was added). (C) Quantification of PGRN–PSAP levels in the medium for experiment in B. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.01, Student’s t test; N.S., no significance.

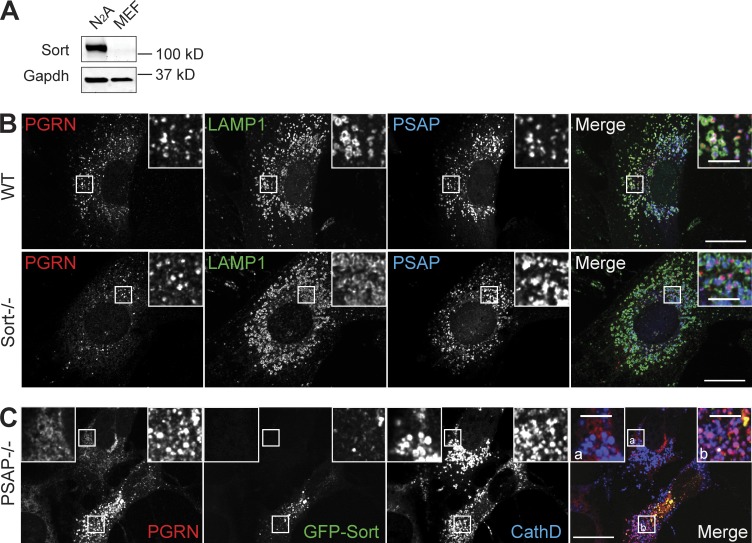

PSAP and sortilin are two independent pathways for PGRN lysosomal trafficking

Previously, we showed that a transmembrane protein of the VPS10 family, sortilin, interacts with PGRN and mediates its lysosomal delivery (Hu et al., 2010). We found that sortilin protein is barely detectable in fibroblasts compared with the neuronal cell line N2a (Fig. 6 A). Consistent with this expression pattern, sortilin is dispensable for PGRN lysosomal trafficking in fibroblasts because PGRN remains localized to lysosomes in sortilin-deficient fibroblasts (Fig. 6 B). Moreover, PSAP-mediated lysosomal delivery of PGRN from the extracellular space is not affected by sortilin deletion in fibroblasts and neurons (Fig. S5). However, ectopic expression of GFP-tagged sortilin in PSAP-deficient fibroblasts fully restored PGRN lysosomal localization (Fig. 6 C). These results demonstrate that sortilin and PSAP are two independent and complementary pathways for PGRN lysosomal trafficking.

Figure 6.

Sortilin and PSAP comprise two independent and complementary pathways for PGRN lysosomal targeting. (A) Immunoblot for sortilin with lysates prepared from fibroblasts and N2a cells. Gapdh was used as a loading control. (B) Immunostaining for PGRN, LAMP1, and PSAP in fibroblasts derived from wild-type and Sort1−/− mice. (C) Ectopic expression of sortilin in PSAP−/− fibroblasts rescues the PGRN trafficking defect. PSAP−/− fibroblasts were transfected with GFP-sortilin. 48 h after transfection, the cells were fixed and stained with sheep anti–mouse PGRN and rabbit anti–Cathepsin D. Representative images from three replicated experiments are shown. Bars: (main) 20 µm; (inset) 5 μm.

PSAP facilitates PGRN lysosomal trafficking through M6PR and LRP1

To identify the trafficking receptors involved in PSAP-mediated lysosomal targeting of PGRN in fibroblasts, we performed a SILAC proteomic screen using FLAG-tagged PSAP as the bait. In addition to several known interactors of PSAP, including PGRN and cathepsins (Zhu and Conner, 1994; Gopalakrishnan et al., 2004), we identified the cation-independent M6PR (also known as IGF2R) as the binding partner for PSAP (Fig. 7 A and Table S2). This binding was supported by the mannose 6-phosphate glycoprotein proteome study using solubilized M6PR as the bait (Sleat et al., 2008) and further confirmed with the coimmunoprecipitation of these proteins (Fig. 7 B). PGRN by itself does not interact with M6PR (Fig. 7 C). However, in the presence of PSAP, PGRN pulls down M6PR efficiently, suggesting that PSAP bridges the binding between PGRN and M6PR (Fig. 7 C). M6PR has previously been shown to play a role in PSAP lysosomal targeting (Vielhaber et al., 1996; Qian et al., 2008). To confirm the role of M6PR in PSAP-mediated PGRN trafficking, we generated M6PR-deficient fibroblasts using the CRISPR technique and examined PSAP and PGRN localization in these cells. M6PR ablation in fibroblasts results in a significant loss of lysosomal localization of both PSAP and PGRN (Fig. 8, A–C). PSAP-mediated lysosomal delivery of PGRN from the extracellular space is also greatly reduced by M6PR deletion (Fig. 8, D and E), indicating that M6PR plays a critical role in PSAP-mediated PGRN lysosomal targeting.

Figure 7.

PSAP interacts with M6PR. (A) Volcano plot of the SILAC experiment using recombinant Flag-PSAP protein to identify interactors from cell lysates prepared from fibroblasts grown in SILAC medium. The top hits are highlighted. (B) PSAP interacts with M6PR. Lysates prepared from PSAP−/− fibroblasts were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated beads with Flag-PSAP or beads only. After washing, the immunoprecipitation products were analyzed by Western blot using anti-M6PR and anti-Flag antibodies. (C) PSAP bridges the binding between PGRN and M6PR. Lysates prepared from PSAP−/− fibroblasts were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated beads with purified FLAG-PGRN or FLAG-PGRN+PSAP or beads only. After washing, the immunoprecipitation products were analyzed by Western blot using anti-M6PR, anti-PSAP, and anti-Flag antibodies. Representative images from three replicated experiments are shown.

Figure 8.

M6PR and LRP1 mediate PGRN–PSAP lysosomal trafficking. (A) Both PSAP and PGRN are mislocalized in M6PR-deficient fibroblasts. Fibroblasts infected with lentiviruses harboring guide RNA against M6PR and Cas9 were selected with puromycin and fixed and stained with goat anti–mouse PSAP or sheep anti–PGRN antibodies as indicated together with rat anti-LAMP1 and rabbit anti-M6PR antibodies. Two neighboring cells with (a) or without (b) M6PR expression are shown. (B and C) Quantification of PSAP (B) and PGRN (C) localization within LAMP1-positive vesicles in control and M6PR−/− fibroblasts as shown in A using ImageJ. Data are given as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments: **, P < 0.01; Student’s t test. (D and E) M6PR is required for PSAP-mediated PGRN lysosomal targeting from the extracellular space. Fibroblasts infected with lentiviruses harboring guide RNA against M6PR and Cas9 were selected with puromycin for a week and treated with recombinant human his-PSAP and human FLAG-PGRN-his proteins (5 µg/ml) in serum-free medium for 12 h, and then stained with hPGRN, LAMP1, and M6PR antibodies. Two neighboring cells with (a) or without (b) M6PR expression are shown. Intensities of endocytosed PGRN were quantified using ImageJ. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments: ***, P < 0.001, Student’s t test. (F and G) LRP1 is also critical for PGRN–PSAP uptake in fibroblasts. Fibroblasts infected with lentiviruses harboring guide RNA against LRP1 and Cas9 were selected with puromycin for 1 wk and treated as in D. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments: ***, P < 0.001, Student’s t test. Bars: (main) 20 µm; (inset) 5 μm.

Besides M6PR, low density LRP1 has also been shown to play a role in PSAP uptake in fibroblasts (Hiesberger et al., 1998). To determine the role of LRP1 in PGRN–PSAP trafficking, we created LRP1−/− fibroblasts using the CRISPR technique. PSAP-dependent PGRN lysosomal delivery from the extracellular space is also significantly reduced in LRP1−/− fibroblasts (Fig. 8, F and G), although we failed to detect an interaction between PSAP and LRP1 in our SILAC screen and in the PSAP pulldown experiment (Table S2 and not depicted). Nevertheless, these experiments demonstrated that both M6PR and LRP1 are critical for PSAP-mediated PGRN lysosomal delivery from the extracellular space.

PSAP regulates PGRN trafficking in vivo

Lysosomal PGRN and PSAP localization is prominent in neurons in the mouse brain, as shown by colocalization with LAMP1 and cathepsin D (Fig. 9, A and B). To determine the in vivo role of PSAP in PGRN lysosomal localization, we examined PGRN localization in wild-type and PSAP−/− mouse brains. Consistent with a previous study, massively enlarged lysosomes were detected in PSAP−/− neurons because of defects in sphingolipid degradation (Fujita et al., 1996). In most cases, the entire PSAP−/− neuron is packed with enlarged lysosomes (Fig. 9 C). More PGRN signals outside of the LAMP1-positive lumen were observed in PSAP−/− neurons compared with wild type (Fig. 9, C and D), although a significant amount of PGRN remains localized in the lysosomal lumen as small puncta in the PSAP−/− neurons, probably because of the high level of neuronal sortilin expression (Fig. 9 B). In contrast, another lysosomal resident protein, cathepsin D, remains in lysosomes labeled by LAMP1 in PSAP−/− neurons (Fig. 9 C), suggesting PSAP is specifically required for PGRN lysosomal targeting in neurons. Consistent with the critical role of PSAP in PGRN lysosomal targeting, serum PGRN levels were increased approximately twofold in PSAP+/− mice and approximately fivefold in PSAP−/− mice (Fig. 9 E). These results strongly support that PSAP plays a critical role in regulating PGRN trafficking in vivo.

Figure 9.

PSAP regulates PGRN trafficking in vivo. (A) PGRN and PSAP colocalize with LAMP1 in cortical neurons of the adult mouse brain. (B) Both sortilin and PSAP are expressed in cortical neurons of the adult mouse brain. (C) Enlarged lysosomes and PGRN mislocalization in cortical neurons of PSAP−/− mice. PSAP−/− and littermate wild-type mice were sacrificed at postnatal day 21 and 15-µm brain sections were stained as indicated. Bars: (main) 20 µm; (inset) 5 μm. (D) Quantification of PGRN signals inside LAMP1-positive vesicles in C using ImageJ. Data are given as mean ± SEM from three pairs of mice: *, P < 0.05, Student’s t test. (E) Serum PGRN levels in newborn wild-type, PSAP+/−, and PSAP−/− littermate mice before the appearance of any apparent lysosomal phenotype in PSAP−/− mice. Data are given as mean ± SEM from four groups of mice. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, one-way analysis of variance.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate a novel interaction between PSAP and PGRN that facilitates lysosomal trafficking of PGRN. We show that this pathway is independent from the previously identified sortilin-mediated lysosomal trafficking of PGRN (Fig. 10). The PSAP and sortilin-dependent PGRN lysosomal targeting mechanisms seem to compensate for each other. In fibroblasts, which express very low levels of sortilin, the PSAP pathway appears essential for PGRN lysosomal targeting, but ectopic expression of sortilin is capable of rescuing PGRN localization in the absence of PSAP. In adult cortical neurons, both PSAP and sortilin are highly expressed (Fig. 9 B) and are critical for PGRN lysosomal trafficking, as demonstrated by a deficiency in either PSAP (Fig. 9, C and D) or sortilin (Hu et al., 2010) causing a lysosomal trafficking defect of PGRN. Ablation of either PSAP (Fig. 9 E) or sortilin (Hu et al., 2010) in mice causes similar changes in serum PGRN levels. A systemic examination of PGRN localization in PSAP−/− and Sort1−/− tissues will allow us to understand tissue-specific PGRN lysosomal trafficking pathways.

Figure 10.

A model for PGRN lysosomal targeting. PSAP and Sortilin are two independent and complementary pathways for PGRN lysosomal targeting in both biosynthetic and endocytic pathways. M6PR and LRP1 are required for PSAP-mediated PGRN lysosomal trafficking.

Several receptors have been shown to mediate PSAP trafficking, including the mannose-6-phosphate receptor (Vielhaber et al., 1996; Qian et al., 2008), sortilin (Lefrancois et al., 2003), and LRP1 (Hiesberger et al., 1998). Among these, both M6PR and LRP1 have been reported to mediate PSAP endocytosis in fibroblasts specifically. Deletion of either M6PR or LRP1 in fibroblasts causes significant reduction in PGRN–PSAP endocytosis (Fig. 8), supporting the finding that PGRN gets a “piggyback ride” from PSAP mainly through M6PR and LRP1 in fibroblasts. Results from our SILAC screen (Fig. 7 A) and coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 7, B and C) clearly demonstrated a direct interaction between PSAP and M6PR. However, we failed to detect an interaction between PSAP and LRP1 in the SILAC screen (Table S2) and in the coimmunoprecipitation experiment (unpublished data). How LRP1 regulates PSAP trafficking remains to be determined. One possiblity could be that the interaction between PSAP and LRP1 is very weak and transient. Alternatively, LRP1 might indirectly regulate PSAP trafficking. Nevertheless, consistent with our findings, a recent study has demonstrated an important role of LRP1 in the M6PR-independent lysosomal delivery of multiple lysosomal luminal proteins from the extracellular space (Markmann et al., 2015).

It is possible that the interaction between PGRN and PSAP plays additional roles in regulating PSAP and PGRN functions besides facilitating PGRN lysosomal trafficking. Processing of PSAP in the endolysosomal compartments generates four saposin peptides (A, B, C, and D) that play critical roles in lysosomal sphingolipid degradation. PSAP and saposin deficiency has been linked to many types of lysosomal storage disorders, including Gaucher disease caused by saposin C deficiency, Krabbe disease caused by saposin A deficiency, and metachromatic leukodystrophy caused by saposin B deficiency (Matsuda et al., 2007). The current study focuses on the role of PSAP in PGRN trafficking. Conversely, PGRN might regulate PSAP processing or saposin function in lysosomes. It is also puzzling that PGRN accumulates in the ER in PSAP−/− fibroblasts. One explanation for the ER localization of PGRN in PSAP−/− cells is that PSAP might facilitate the trafficking of PGRN from the ER to the Golgi. However, the increased secretion of PGRN in PSAP−/− cells fails to support this possibility, although it remains to be determined whether PSAP affects the kinetics of PGRN transport from the ER to the Golgi. Additionally, it is known that both PGRN and PSAP are secreted and have neurotrophic functions (Ahmed et al., 2007; Meyer et al., 2014). Their comparable levels secreted in human serum (Ghidoni et al., 2008; Finch et al., 2009; Koochekpour et al., 2012) and the 1:1 stoichiometric interaction between PGRN and PSAP (Fig. 2 D) support the idea that these two proteins might form a complex extracellularly to promote cell survival.

How PGRN functions in lysosomes is another mystery. One hypothesis is that PGRN is processed into granulin peptides in lysosomes (Cenik et al., 2012). Future proteomic studies to identify PGRN/GRN binding partners in lysosomes will help us understand their critical roles in regulating lysosomal activities. Recently, PGRN has also been shown to regulate the activity of TFEB through mTORC1 signaling in microglia after injury (Tanaka et al., 2013). How PGRN/GRN regulates mTORC1 is still not clear. Although this could be a signaling function of PGRN from the extracellular space, another intriguing possibility is that GRN regulates mTORC1 from inside lysosomes, as mTORC1 activities have been shown to be regulated by amino acid flux from the lysosomal lumen (Zoncu et al., 2011).

Endolysosomal dysfunction has been implicated in many neurodegenerative diseases, including FTLD-U. Correspondingly, VCP/p97 and CHMP2B, two FTLD-U–associated genes, are involved in membrane trafficking and autophagy (Lee and Gao, 2008; Rusten and Simonsen, 2008; Ju et al., 2009). The FTLD-U risk factor TMEM106B regulates lysosomal morphology and function (Brady et al., 2013). The newly identified mutated gene in FTLD-U/ALS, C9Orf72, might also be involved in membrane trafficking (Farg et al., 2014). Furthermore, accumulating evidence suggests a critical role of PGRN in lysosomes. The fact that total loss of PGRN results in NCL and haploinsufficiency of PGRN leads to FTLD-U indicates that these two diseases are linked to each other and lysosomal dysfunction might serve as a common disease mechanism. In line with this, a recent study has found that NCL patients develop pathological TDP-43 phosphorylation, which is typically seen in FTLD patients, and FTLD-U/GRN patients have NCL-like pathology (Götzl et al., 2014). Future studies on PGRN–PSAP interactions and function of PGRN/granulin peptides in lysosomes will reveal novel insights into the cellular processes that might be affected in FTLD-U, NCL, and possibly other neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Materials and methods

DNA and plasmids

Human PSAP cDNA in the pDONR223 vector was a gift from H. Yu (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY). His- and FLAG-tagged PSAP construct was obtained by cloning PSAP into pSectag2B vector (Invitrogen). PSAP-V5 construct was obtained through a gateway reaction with pDONR223-PSAP entry vector and pDEST6.2 destination vector (Invitrogen). GST-PSAP construct was obtained by cloning mouse PSAP into the pGEX 6p-1 vector (GE Healthcare). PGRN constructs were previously described (Hu et al., 2010). His-tagged human PSAP construct was generated by cloning human PSAP cDNA into pSectag2 vector with a 6× his tag after signal sequence. GFP-PGRN was constructed by replacing the AP sequence with GFP in the pAP5-PGRN plasmid (Hu et al., 2010). N-terminal tagged mCherry-PSAP was cloned into pCDH-puro lentiviral vector.

For the mouse PSAP shRNA targeting construct, the targeting sequence 5′-GGAACTTGCTGAAAGATAA-3′, together with short hairpins, was cloned into the BglII and XhoI sites of the pSuper vector.

CRISPR-mediated genome editing

To generate CRISPR constructs, two oligonucleotides with the sequences 5′-CACCGAAGAGGGCGAGGGCGTACA-3′ and 5′-AAACTGTACGCCCTCGCCCTCTTC-3′ (mouse PSAP), the sequences 5′-CACCGGCCCCACGCCACACGCGATG-3′ and 5′-AAACCATCGCGTGTGGCGTGGGGCC-3′ (mouse CI-M6PR), and the sequences 5′-CACCGGGGCTTCATCAGAGCCGTCG-3′ and 5′-AAACCGACGGCTCTGATGAAGCCCC-3′ (mouse LRP1) were annealed and ligated to pLenti-CRISPRv2 (52961; Addgene) digested with BsmB1. Lentiviruses were generated by transfecting lentiviral vectors together with pMD2.G and psPAX2 plasmids.

For CRISPR-mediated genome editing, fibroblasts were infected with lentiviruses containing pLenti-CRISPRv2 harboring guide RNA sequences targeted to mouse PSAP, LRP1, or CI-M6PR. Cells were selected with 2 µg/ml puromycin and assayed 1 wk after selection. The efficiency of gene knockout was confirmed by both immunostaining and Western blot analysis.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: mouse anti-FLAG (M2) and rabbit anti-LRP1 from Sigma-Aldrich, rabbit anti-PDI from Thermo Fisher Scientific, mouse anti-GAPDH from Proteintech Group, mouse anti-V5 from Invitrogen, and rat anti–mouse LAMP1 (1D4B) from BD. Sheep anti–mouse PGRN and goat anti–human PGRN antibodies were obtained from R&D Systems. Rabbit anti–mouse PSAP and PGRN antibodies were generated by Pocono Rabbit Farm and Laboratory using the recombinant Gst-PSAP proteins purified from bacteria or FLAG-tagged PGRN from HEK293T cells as the antigen. Rabbit anti-–human saposin B antibodies (Leonova et al., 1996) and goat anti–mouse PSAP antibodies (Sun et al., 2005) were described previously. Rabbit anti–cathepsin D and anti-M6PR antibodies were homemade by W. Brown’s laboratory (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY; Park et al., 1991). The homemade anti-TMEM106B antibodies have been characterized previously (Brady et al., 2013).

Mouse strains

C57/BL6 and PGRN−/− (Yin et al., 2010) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and housed in the Weill Hall animal facility. Sortilin knockout mice (Nykjaer et al., 2004) were a gift from S. Strittmatter (Yale University, New Haven, CT) and A. Nykjaer (Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark). PSAP−/− mice were previously described (Fujita et al., 1996).

Cell culture, DNA transfection, and virus infection

HEK293T, T98G, and BV2 cells were maintained in DMEM (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen) in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were transiently transfected with polyethyleneimine as described previously (Vancha et al., 2004). FH14 cells stably expressing FLAG-human-PGRN-6Xhis were a gift from A. Ding (Weill Medical College, New York, NY). FH14 cells were grown in DMEM + 10% FBS + 100 µg/ml hygromycin.

Retroviruses were generated by transfecting pSuper-mPSAP shRNA or control shRNA construct together with pCMV-VSVG in Phoenix 293T cells.

Primary cortical neurons were isolated from P0–P1 pups using a modified protocol (Beaudoin et al., 2012). Cortices were rapidly dissected from the brain in 2 ml HBSS supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen) and 0.5 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen) at 4°C. Meninges and excess white matter were removed before digestion with papain (2 mg/ml in HBSS; Worthington) and DNaseI (1 mg/ml in HBSS; Sigma-Aldrich) for 12 min at 37°C. Tissues were then dissociated using fire-polished glass pipettes. Cells were spun down and resuspended in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) plus B27 and plated onto poly-lysine (Sigma-Alsrich)–coated dishes.

Primary mouse fibroblasts were isolated from wild-type, PGRN−/−, Sort1−/−, and PSAP−/− mouse newborn pups and grown in DMEM plus 10% FBS.

Protein purification

GST-PSAP proteins were purified using Gst beads from Origami B(DE3) bacterial strains (EMD Millipore) after 0.1 mM IPTG induction overnight at 20°C. The proteins were eluted with glutathione. FLAG-PGRN-his protein was purified from the serum-free culture medium of FH14 cells (HEK293T cells stably expressing FLAG-human-PGRN-6Xhis) using cobalt beads. Protein was eluted with imidazole. His-tagged human PSAP was purified from the culture medium (serum free) of HEK293T cells transfected with his-PSAP construct using cobalt beads. All purified proteins were further concentrated and changed to PBS buffer using the Centricon device (EMD Millipore).

SILAC and mass spectrometry analysis

T98G cells and immortalized fibroblasts were grown a minimum of five generations in DMEM with 10% dialyzed FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with either light (C12, N14 arginine and lysine) or heavy (C13, N15 arginine and lysine) amino acids. To search for PGRN interactors, the heavy T98G cells were transfected in two 15-cm dishes with GFP-PGRN expression constructs, whereas the light T98G cells were transfected with pEGFP-C1 as a control. 2 d after transfection, cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% deoxycholic acid with protease inhibitors (Roche). The lysates were subjected to anti-GFP immunoprecipitation using GFP-Trap beads (ChromoTek). The presence of GFP and GFP-PGRN in immunoprecipitated samples was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. Samples were then mixed and boiled 5 min with 1% DTT followed by alkylation by treating samples with a final concentration of 28 mM iodoacetamide. Proteins were precipitated on ice for 30 min with a mixture of 50% acetone/49.9% ethanol/0.1% acetic acid. Protein was pelleted and washed with this buffer, reprecipitated on ice, and dissolved in 8 M urea/50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) followed by dilution with three volumes of 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0)/150 mM NaCl. Proteins were digested overnight at 37°C with 1 µg of mass spectrometry grade Trypsin (Promega). The resulting peptide samples were cleaned up for mass spectrometry by treatment with 10% formic acid and 10% trifluoroacetic acid and washed twice with 0.1% acetic acid on preequilibrated Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (Waters). Samples were eluted with 80% acetonitrile/0.1% acetic acid into silanized vials (National Scientific) and evaporated using a SpeedVac. Samples were redissolved in H2O with ∼1% formic acid and 70% acetonitrile. Peptides were separated using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography on an Ultimate 300 LC (Dionex). Each fraction was evaporated with a SpeedVac and resuspended in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid with 0.1 pM angiotensin internal standard. Samples were run on an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and data were analyzed using the SORCERER system (Sage-N Research). To search for PSAP interactors, lysates prepared from heavy labeled fibroblasts were incubated with purified FLAG-PSAP bound to anti-FLAG antibody–conjugated agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich), whereas lysates from light-labeled fibroblasts were incubated with beads only. After 4-h incubation, beads were washed and the eluted samples were analyzed as described for GFP-PGRN SILAC.

Immunoprecipitation and protein analysis

Cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris, pH8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% deoxycholic acid with protease inhibitors (Roche). The lysates were subject to anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody–conjugated beads (Sigma-Aldrich) or incubated with anti-PGRN antibodies followed by protein G beads (Genscript). Beads were washed with 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100 after 4 h of incubation. Western blot was visualized using the Licor-Odyssey system as described previously (Brady et al., 2013).

To determine the direct interaction between purified PGRN and PSAP, proteins were mixed in PBS + 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h before incubating with anti-FLAG antibody–conjugated beads for another 2 h. Beads were washed three times with PBS + 0.2% Triton X-100. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE and the gel is stained with Krypton dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and scanned using the Licor-Odyssey system.

The PGRN and PSAP levels in the medium were analyzed after trichloroacetic acid precipitation as described previously (Brady et al., 2013).

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 0.05% saponin, and visualized using immunofluorescence microscopy as previously described (Brady et al., 2013). For brain staining, mice were perfused and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. 10-µm-thick brain sections were cut with a cryotome. Tissue sections were blocked and permeabilized with 0.05% saponin in Odyssey blocking buffer before incubating with primary antibodies overnight.

Microscope image acquisition

Microscope image acquisition was performed at room temperature (21°C) on a CSU-X spinning disc confocal microscope system (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) using an inverted microscope (DMI600B; Leica), 100×/1.46 NA objective, and the CoolSnap HQ2 camera (Photometrics). Micrographs were acquired in Slidebook (Intelligent Imaging Innovations), which was also used to create single and merged images.

Quantitative analysis of lysosomal PSAP, PGRN, and endocytosed PGRN

The ImageJ program was used to process images. To quantify the degree of colocalization between PSAP or PGRN and the lysosomal marker LAMP1, the JACoP plugin was used to generate Manders’ coefficients (Bolte and Cordelières, 2006). To quantify endocytosed PGRN, the entire cell was selected and the fluorescence intensity was measured directly by ImageJ. For each experiment, at least 12 pairs of cells were measured and the data from three or four independent experiments were used for statistical analysis.

ELISA

Serum samples were collected from newborn pups and analyzed using mouse PGRN ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance between multiple groups was compared by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Two-group analysis was performed using the Student’s t test. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism4 software (GraphPad Software).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows coomassie staining of SDS-PAGE with purified Flag-PGRN-his and PSAP proteins used in this study. Fig. S2 shows that PGRN is not required for PSAP lysosomal targeting in fibroblasts. Fig. S3 shows mislocalization of PGRN in fibroblasts with PSAP expression knocked down by shRNA or ablated with CRISPR. Fig. S4 shows that PSAP facilitates PGRN lysosomal targeting from the extracellular space in neurons. Fig. S5 shows that PSAP facilitates PGRN lysosomal targeting from the extracellular space in Sort1−/− fibroblasts and neurons. Table S1 lists SILAC hits identified with GFP-PGRN in T98G cells. Table S2 lists SILAC hits identified with FLAG-PSAP pull-down in fibroblasts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Haiyuan Yu for his kind gifts of cDNAs and Dr. Anders Nykjaer and Dr. Stephen Strittmatter for providing sortilin knockout mice. We thank Dr. Ling Fang for his help with CRISPR; Xiaochun Wu for technical assistance; and Daniel Paushter, Peter Sullivan, and Kevin Dean Thorsen for proofreading the manuscript.

This work is supported by funding to F. Hu from Weill Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Association of Frontotemporal Dementia, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R21 NS081357-01 and R01NS088448-01) and by funding to X. Zhou from the Weill Institute Fleming Postdoctoral Fellowship.

The authors declare no additional competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- CRISPR

- clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- FTLD

- frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- LRP1

- lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1

- M6PR

- mannose 6-phosphate receptor

- NCL

- neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis

- PDI

- protein disulfide isomerase

- PGRN

- progranulin

- PSAP

- prosaposin

- SILAC

- stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture

References

- Ahmed Z., Mackenzie I.R., Hutton M.L., and Dickson D.W.. 2007. Progranulin in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation. 4:7 10.1186/1742-2094-4-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z., Sheng H., Xu Y.F., Lin W.L., Innes A.E., Gass J., Yu X., Wuertzer C.A., Hou H., Chiba S., et al. . 2010. Accelerated lipofuscinosis and ubiquitination in granulin knockout mice suggest a role for progranulin in successful aging. Am. J. Pathol. 177:311–324. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida S., Zhou L., and Gao F.B.. 2011. Progranulin, a glycoprotein deficient in frontotemporal dementia, is a novel substrate of several protein disulfide isomerase family proteins. PLoS ONE. 6:e26454 10.1371/journal.pone.0026454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M., Mackenzie I.R., Pickering-Brown S.M., Gass J., Rademakers R., Lindholm C., Snowden J., Adamson J., Sadovnick A.D., Rollinson S., et al. . 2006. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 442:916–919. 10.1038/nature05016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin G.M. III, Lee S.H., Singh D., Yuan Y., Ng Y.G., Reichardt L.F., and Arikkath J.. 2012. Culturing pyramidal neurons from the early postnatal mouse hippocampus and cortex. Nat. Protoc. 7:1741–1754. 10.1038/nprot.2012.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcastro V., Siciliano V., Gregoretti F., Mithbaokar P., Dharmalingam G., Berlingieri S., Iorio F., Oliva G., Polishchuck R., Brunetti-Pierri N., and di Bernardo D.. 2011. Transcriptional gene network inference from a massive dataset elucidates transcriptome organization and gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:8677–8688. 10.1093/nar/gkr593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellettato C.M., and Scarpa M.. 2010. Pathophysiology of neuropathic lysosomal storage disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 33:347–362. 10.1007/s10545-010-9075-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte S., and Cordelières F.P.. 2006. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc. 224:213–232. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady O.A., Zheng Y., Murphy K., Huang M., and Hu F.. 2013. The frontotemporal lobar degeneration risk factor, TMEM106B, regulates lysosomal morphology and function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22:685–695. 10.1093/hmg/dds475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenik B., Sephton C.F., Kutluk Cenik B., Herz J., and Yu G.. 2012. Progranulin: a proteolytically processed protein at the crossroads of inflammation and neurodegeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 287:32298–32306. 10.1074/jbc.R112.399170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Plotkin A.S., Unger T.L., Gallagher M.D., Bill E., Kwong L.K., Volpicelli-Daley L., Busch J.I., Akle S., Grossman M., Van Deerlin V., et al. . 2012. TMEM106B, the risk gene for frontotemporal dementia, is regulated by the microRNA-132/212 cluster and affects progranulin pathways. J. Neurosci. 32:11213–11227. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0521-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Ran F.A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P.D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L.A., and Zhang F.. 2013. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 339:819–823. 10.1126/science.1231143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook C., Stetler C., and Petrucelli L.. 2012. Disruption of protein quality control in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a009423 10.1101/cshperspect.a009423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruts M., Gijselinck I., van der Zee J., Engelborghs S., Wils H., Pirici D., Rademakers R., Vandenberghe R., Dermaut B., Martin J.J., et al. . 2006. Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature. 442:920–924. 10.1038/nature05017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farg M.A., Sundaramoorthy V., Sultana J.M., Yang S., Atkinson R.A., Levina V., Halloran M.A., Gleeson P.A., Blair I.P., Soo K.Y., et al. . 2014. C9ORF72, implicated in amytrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia, regulates endosomal trafficking. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23:3579–3595. 10.1093/hmg/ddu068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch N., Baker M., Crook R., Swanson K., Kuntz K., Surtees R., Bisceglio G., Rovelet-Lecrux A., Boeve B., Petersen R.C., et al. . 2009. Plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutation status in frontotemporal dementia patients and asymptomatic family members. Brain. 132:583–591. 10.1093/brain/awn352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita N., Suzuki K., Vanier M.T., Popko B., Maeda N., Klein A., Henseler M., Sandhoff K., Nakayasu H., and Suzuki K.. 1996. Targeted disruption of the mouse sphingolipid activator protein gene: a complex phenotype, including severe leukodystrophy and wide-spread storage of multiple sphingolipids. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5:711–725. 10.1093/hmg/5.6.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass J., Cannon A., Mackenzie I.R., Boeve B., Baker M., Adamson J., Crook R., Melquist S., Kuntz K., Petersen R., et al. . 2006. Mutations in progranulin are a major cause of ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15:2988–3001. 10.1093/hmg/ddl241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidoni R., Benussi L., Glionna M., Franzoni M., and Binetti G.. 2008. Low plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 71:1235–1239. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000325058.10218.fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan M.M., Grosch H.W., Locatelli-Hoops S., Werth N., Smolenová E., Nettersheim M., Sandhoff K., and Hasilik A.. 2004. Purified recombinant human prosaposin forms oligomers that bind procathepsin D and affect its autoactivation. Biochem. J. 383:507–515. 10.1042/BJ20040175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götzl J.K., Mori K., Damme M., Fellerer K., Tahirovic S., Kleinberger G., Janssens J., van der Zee J., Lang C.M., Kremmer E., et al. . 2014. Common pathobiochemical hallmarks of progranulin-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Acta Neuropathol. 127:845–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiesberger T., Hüttler S., Rohlmann A., Schneider W., Sandhoff K., and Herz J.. 1998. Cellular uptake of saposin (SAP) precursor and lysosomal delivery by the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP). EMBO J. 17:4617–4625. 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F., Padukkavidana T., Vægter C.B., Brady O.A., Zheng Y., Mackenzie I.R., Feldman H.H., Nykjaer A., and Strittmatter S.M.. 2010. Sortilin-mediated endocytosis determines levels of the frontotemporal dementia protein, progranulin. Neuron. 68:654–667. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J.S., Fuentealba R.A., Miller S.E., Jackson E., Piwnica-Worms D., Baloh R.H., and Weihl C.C.. 2009. Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. J. Cell Biol. 187:875–888. 10.1083/jcb.200908115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koochekpour S., Hu S., Vellasco-Gonzalez C., Bernardo R., Azabdaftari G., Zhu G., Zhau H.E., Chung L.W., and Vessella R.L.. 2012. Serum prosaposin levels are increased in patients with advanced prostate cancer. Prostate. 72:253–269. 10.1002/pros.21427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C.M., Fellerer K., Schwenk B.M., Kuhn P.H., Kremmer E., Edbauer D., Capell A., and Haass C.. 2012. Membrane orientation and subcellular localization of transmembrane protein 106B (TMEM106B), a major risk factor for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 287:19355–19365. 10.1074/jbc.M112.365098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.A., and Gao F.B.. 2008. ESCRT, autophagy, and frontotemporal dementia. BMB Rep. 41:827–832. 10.5483/BMBRep.2008.41.12.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancois S., Zeng J., Hassan A.J., Canuel M., and Morales C.R.. 2003. The lysosomal trafficking of sphingolipid activator proteins (SAPs) is mediated by sortilin. EMBO J. 22:6430–6437. 10.1093/emboj/cdg629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonova T., Qi X., Bencosme A., Ponce E., Sun Y., and Grabowski G.A.. 1996. Proteolytic processing patterns of prosaposin in insect and mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271:17312–17320. 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K.M., Aach J., Guell M., DiCarlo J.E., Norville J.E., and Church G.M.. 2013. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 339:823–826. 10.1126/science.1232033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markmann S., Thelen M., Cornils K., Schweizer M., Brocke-Ahmadinejad N., Willnow T., Heeren J., Gieselmann V., Braulke T., and Kollmann K.. 2015. Lrp1/LDL receptor play critical roles in mannose 6-phosphate-independent lysosomal enzyme targeting. Traffic. 16:743–759. 10.1111/tra.12284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda J., Yoneshige A., and Suzuki K.. 2007. The function of sphingolipids in the nervous system: lessons learnt from mouse models of specific sphingolipid activator protein deficiencies. J. Neurochem. 103:32–38. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R.C., Giddens M.M., Coleman B.M., and Hall R.A.. 2014. The protective role of prosaposin and its receptors in the nervous system. Brain Res. 1585:1–12. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R.A., and Cataldo A.M.. 2006. Lysosomal system pathways: genes to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 9:277–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R.A., Yang D.S., and Lee J.H.. 2008. Neurodegenerative lysosomal disorders: a continuum from development to late age. Autophagy. 4:590–599. 10.4161/auto.6259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykjaer A., Lee R., Teng K.K., Jansen P., Madsen P., Nielsen M.S., Jacobsen C., Kliemannel M., Schwarz E., Willnow T.E., et al. . 2004. Sortilin is essential for proNGF-induced neuronal cell death. Nature. 427:843–848. 10.1038/nature02319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J.S., and Kishimoto Y.. 1991. Saposin proteins: structure, function, and role in human lysosomal storage disorders. FASEB J. 5:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.E., Draper R.K., and Brown W.J.. 1991. Biosynthesis of lysosomal enzymes in cells of the End3 complementation group conditionally defective in endosomal acidification. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 17:137–150. 10.1007/BF01232971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X., and Grabowski G.A.. 2001. Molecular and cell biology of acid β-glucosidase and prosaposin. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 66:203–239. 10.1016/S0079-6603(00)66030-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian M., Sleat D.E., Zheng H., Moore D., and Lobel P.. 2008. Proteomics analysis of serum from mutant mice reveals lysosomal proteins selectively transported by each of the two mannose 6-phosphate receptors. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 7:58–70. 10.1074/mcp.M700217-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusten T.E., and Simonsen A.. 2008. ESCRT functions in autophagy and associated disease. Cell Cycle. 7:1166–1172. 10.4161/cc.7.9.5784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleat D.E., Della Valle M.C., Zheng H., Moore D.F., and Lobel P.. 2008. The mannose 6-phosphate glycoprotein proteome. J. Proteome Res. 7:3010–3021. 10.1021/pr800135v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.R., Damiano J., Franceschetti S., Carpenter S., Canafoglia L., Morbin M., Rossi G., Pareyson D., Mole S.E., Staropoli J.F., et al. . 2012. Strikingly different clinicopathological phenotypes determined by progranulin-mutation dosage. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90:1102–1107. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Quinn B., Witte D.P., and Grabowski G.A.. 2005. Gaucher disease mouse models: point mutations at the acid β-glucosidase locus combined with low-level prosaposin expression lead to disease variants. J. Lipid Res. 46:2102–2113. 10.1194/jlr.M500202-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Matsuwaki T., Yamanouchi K., and Nishihara M.. 2013. Increased lysosomal biogenesis in activated microglia and exacerbated neuronal damage after traumatic brain injury in progranulin-deficient mice. Neuroscience. 250:8–19. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancha A.R., Govindaraju S., Parsa K.V., Jasti M., González-García M., and Ballestero R.P.. 2004. Use of polyethyleneimine polymer in cell culture as attachment factor and lipofection enhancer. BMC Biotechnol. 4:23 10.1186/1472-6750-4-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vielhaber G., Hurwitz R., and Sandhoff K.. 1996. Biosynthesis, processing, and targeting of sphingolipid activator protein (SAP) precursor in cultured human fibroblasts. Mannose 6-phosphate receptor-independent endocytosis of SAP precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 271:32438–32446. 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F., Banerjee R., Thomas B., Zhou P., Qian L., Jia T., Ma X., Ma Y., Iadecola C., Beal M.F., et al. . 2010. Exaggerated inflammation, impaired host defense, and neuropathology in progranulin-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 207:117–128. 10.1084/jem.20091568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Brady O.A., Meng P.S., Mao Y., and Hu F.. 2011. C-terminus of progranulin interacts with the β-propeller region of sortilin to regulate progranulin trafficking. PLoS ONE. 6:e21023 10.1371/journal.pone.0021023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., and Conner G.E.. 1994. Intermolecular association of lysosomal protein precursors during biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 269:3846–3851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu R., Bar-Peled L., Efeyan A., Wang S., Sancak Y., and Sabatini D.M.. 2011. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H+-ATPase. Science. 334:678–683. 10.1126/science.1207056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.