A RANK ligand-specific inhibitor, denosumab, was predicted to reduce osteolysis and control disease progression in patients with giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB). We report, for the first time, the results of the response of GCTB to denosumab obtained from a prospective independent imaging assessment. The findings demonstrate that denosumab has robust clinical efficacy in the treatment of GCTB.

Keywords: giant cell tumor of bone, denosumab, RANKL, primary bone tumor, objective tumor response

Abstract

Background

Giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB) is a rare primary bone tumor, characterized by osteoclast-like giant cells that express receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK), and stromal cells that express RANK ligand (RANKL), a key mediator of osteoclast activation. A RANKL-specific inhibitor, denosumab, was predicted to reduce osteolysis and control disease progression in patients with GCTB.

Patients and methods

Seventeen patients with GCTB were enrolled. Patients were treated with denosumab at 120 mg every 4 weeks, with a loading dose of 120 mg on days 8 and 15. To evaluate efficacy, objective tumor response was evaluated prospectively by an independent imaging facility on the basis of prespecified criteria.

Results

The proportion of patients with an objective tumor response was 88% based on best response using any tumor response criteria. The proportion of patients with an objective tumor response using individual response criteria was 35% based on the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria, 82% based on the modified European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) criteria, and 71% based on inverse Choi criteria. The median time of study treatment was 13.1 months.

Conclusion

The findings demonstrate that denosumab has robust clinical efficacy in the treatment of GCTB.

introduction

Giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB) is a primary bone tumor that presents as an eccentric osteolytic lesion frequently affecting the epiphyseal portion of long bones, or the spine or sacrum. GCTB typically occurs in young adults in the third or fourth decade of life. GCTB is characterized by rapid growth, severe destruction of bone, and extension into the surrounding soft tissues. Metastatic spread occurs in 1%–3% of patients with GCTB, most frequently to lung [1]. Surgery can be curative if adequate resection of the tumor is carried out [2]; however, aggressive surgical procedures such as megaprosthesis replacement after wide local excisions, or amputation/hemipelvectomy, both of which can result in significant postoperative morbidity, may be required. In the absence of en bloc complete resection of the primary tumor, recurrence is common [3]. In patients with unresectable GCTB, radiation therapy may control local tumor growth [4]; however, there is a risk of malignant transformation [5]. Embolization may provide symptomatic relief [6], but a durable response is uncommon. The use of bisphosphonates, chemotherapeutics, interferon, or other drugs has been reported, but none of these drugs provided consistent sustained responses.

GCTB is characterized by osteoclast-like giant cells and their precursors that express receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK), and mononuclear stromal cells that express RANK ligand (RANKL), a key mediator of osteoclast activation. Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits RANKL, thereby preventing RANK–RANKL interactions and GCTB-induced bone destruction [7]. Results from the first phase II study of denosumab showed a tumor response in 30 of 35 patients with GCTB [8]. In the larger subsequent phase II study, 163 of 169 (96%) analyzable patients with unresectable GCTB showed no disease progression on the basis of the investigators' assessment of disease status. Seventy-four of 100 (74%) analyzable patients with resectable GCTB had no surgery, and 16 of 26 (62%) patients who had surgery underwent less morbid procedures than planned [9]. We conducted this phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of denosumab for the treatment of Japanese patients with GCTB. We report, for the first time, results of a prospective open-label study that included independent imaging assessment of the efficacy of denosumab in the treatment of GCTB.

methods

study design and patients

Our study was an open-label, phase II trial at five centers in Japan. We did a prespecified analysis of the 12-month cutoff data, which was conducted at the time when more than 10 patients were projected to have completed 12 months of treatment.

Eligible patients were adults or skeletally mature adolescents who had radiographic evidence of at least one mature long bone (i.e. closed epiphyseal plates), were at least 12 years old and weighed at least 45 kg. Patients had histologically confirmed GCTB and radiographically measurable active disease within 1 year of study enrollment and Karnofsky performance status of 50% or greater. Histopathology tests were carried out in each tertiary referral center for bone and soft-tissue tumors. Only pathological reports were collected.

Key exclusion criteria were: current use of alternative GCTB treatments (e.g. radiation, chemotherapy, embolization, bisphosphonates); known or suspected diagnosis of sarcoma, non-GCTB giant-cell-rich tumors, brown cell tumor of bone, or Paget's disease; diagnosis of second malignancy within the past 5 years; history or current evidence of osteonecrosis or osteomyelitis of the jaw; active dental or jaw conditions necessitating oral surgery, or unhealed dental or oral surgery; or pregnancy.

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and Good Clinical Practice. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each study center. All patients provided written informed consent.

procedures

Patients received s.c. injection of denosumab (120 mg) every 4 weeks, with additional loading doses on days 8 and 15. This treatment continued until disease progression, recommendation of discontinuation by the investigator or sponsor, absence of clinical benefit according to the investigator's judgment, or patients' decision to discontinue. All patients received vitamin D (≥400 IU) and calcium (≥600 mg) supplementation daily throughout the study, except in cases with pre-existing hypercalcemia. Denosumab plasma concentration levels were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Investigators carried out imaging by CT/MRI and 18FDG–PET/PET–CT of target lesion and nontarget lesion every 12 weeks for 49 weeks and every 24 weeks thereafter. Imaging equipment, scan site, and scanning parameters (e.g. field of view, size) were consistent throughout the study. Investigator-determined disease status and clinical benefit were assessed every 4 weeks, based on physical examination, patients' reports of symptoms, and radiological imaging assessments. Patients assessed worst pain severity using Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) at baseline and each study visit [10]. Bone turnover markers were assessed every 4 weeks.

Our prespecified primary end point was the proportion of patients with an objective tumor response [defined as a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR)]. A central imaging facility (BioClinica, Princeton, NJ) did a prospective independent review of the images on the basis of prespecified criteria. Baseline and on-study generated images (e.g. CT/MRI and PET/PET–CT) were assessed at the central imaging facility to determine tumor response. The images were assessed by two trained radiology reviewers who were blinded regarding the investigators' assessments, investigators' choices of target and nontarget lesions, and identification of new lesions. A third reviewer adjudicated the findings when necessary.

An objective tumor response was assessed on the basis of best response [CR, PR, stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD)] as measured by any tumor response criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Objective tumor response criteria

| Modified RECIST version 1.1 criteria | ||

|---|---|---|

| Response | Target lesion evaluation | Nontarget lesion evaluation |

| Complete response (CR) | Disappearance of all target lesions. All target lymph nodes are <10 mm in short axis. | Disappearance of all nontarget lesions. All nontarget lymph nodes are <10 mm in the short axis. |

| Partial response (PR) | ≥30% decrease in sum of the lesion diameters (SLD) using baseline SLD as reference. | – |

| Stable disease (SD) | Neither PR nor PD, using nadir SLD (or baseline if it is nadir). | Non-CR or non-PD. |

| Progressive disease (PD) | ≥20% increase in SLD + 5 mm absolute increase. | The unequivocal progression of existing nontarget lesion(s). |

| Unable to evaluate (UE) | A target lesion present at screening, but which subsequently became unevaluable. | Any nontarget lesion present at screening, but which subsequently became unevaluable. |

| Modified EORTC criteriaa | ||

| Response | PET target lesion evaluation | |

| CR | Complete resolution of abnormal FDG uptake within the tumor volume of all target lesions to a level which is indistinguishable from surrounding normal tissue. | |

| PR | %ΔΣSUVmax decrease of ≥25% compared with screening. | |

| SD | %ΔΣSUVmax increased by <25% or decreased by <25% compared with screening. | |

| PD | %ΔΣSUVmax increased by ≥25% compared with screening. | |

| UE | The FDG–PET exam is unavailable or, if received, is deemed unevaluable leading to an inability to determine the status of the identified target lesion for the time point in question. If one of the target lesions is deemed unevaluable, and the rules for PD do not apply, a response of CR, PR or SD cannot be assigned for that time point and the response will be UE, unless unequivocal progression is determined on the basis of the evaluable target lesions. | |

| Modified inverse Choi (density/size) criteriab | ||

| Response | Lesion evaluation | |

| CR | Disappearance of all disease. | |

| PR | A decrease in the Choi SLD ≥10% or, an increase in CT density [%ΔHounsfield Unit (HU) mean] ≥15% compared with screening. | |

| SD | Does not meet the criteria for CR, PR or PD. | |

| PD | An increase in unidimensional tumor size (Choi SLD) of >10% and does not meet the criteria for PR using CT density. Note: The identification of any new lesion(s) identified on CT/MRI will result in a determination of PD. |

|

| UE | The CT/MRI exam is unavailable or, if received, is deemed unevaluable leading to an inability to determine the density and/or size measurement on CT/MRI of the identified target lesions for the time point in question. If a target lesion is deemed unevaluable by density and size measurement, and the rules for PD do not apply, a response of CR, PR or SD cannot be assigned for that time point and the response will be UE. | |

aTo assess metabolic response on the basis of standardized uptake value (SUV) of 18FDG–PET.

bTo assess lesion density and size (Hounsfield units were used on CT and the longest diameter measured on CT or MRI). This criteria measure an increase in lesion density instead of the decrease in density associated with tumor response in non-GCTB tumors. This GCTB-specific modification of Choi criteria was based on histological changes noted in response to denosumab treatment (ossification or calcification), which represent new bone formation [9, 11].

Secondary end points were proportion of patients with an objective tumor response that was sustained; proportion of patients with an objective tumor response using each tumor response criterion; time to first objective tumor response; and duration of objective tumor response.

Adverse events and laboratory abnormalities were assessed with Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE; version 4.0).

statistical methods

As prespecified in the protocol, efficacy analysis set included all enrolled subjects, excluding those who had not received administration of the investigational product and had no available primary end point data. Efficacy analyses were carried out using the efficacy analysis set. An objective tumor response was defined as the best response using any tumor response criteria. The primary efficacy end point, the proportion of subjects with an objective tumor response, was summarized using crude estimates with two-sided exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For the proportion end point, crude estimates with two-sided exact 95% CIs were summarized. For the time-to-event end point or the duration of response, Kaplan–Meier estimates were graphically displayed, and Kaplan–Meier estimates of quartiles with two-sided 95% CIs were calculated if applicable. This study is registered with JAPIC Clinical Trial Information (JapicCTI-111665).

results

A total of 17 patients were enrolled in this study, and all patients received at least one dose of denosumab. Nine patients were women; eight patients were men. The median age was 30 (range, 18–66) years. Four patients (24%) had either primary or recurrent resectable GCTB, and 13 (76%) had primary or recurrent unresectable GCTB (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

| All patients (N = 17) | |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 9 (53) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 30 |

| Minimum, maximum | 18, 66 |

| GCTB disease type, n (%) | |

| Primary resectable | 2 (12) |

| Primary unresectable | 5 (29) |

| Recurrent resectable | 2 (12) |

| Recurrent unresectable | 8 (47) |

| Location of target lesion, n (%) | |

| Sacrum | 5 (29) |

| Lung | 3 (18) |

| Tibia | 2 (12) |

| Femur | 1 (6) |

| Humerus | 1 (6) |

| Lumbar vertebrae | 1 (6) |

| Pelvic bone | 1 (6) |

| Pleura | 1 (6) |

| Radius | 1 (6) |

| Skull | 1 (6) |

| Previous treatment of GCTB, n (%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 1 (6) |

| Radiation | 0 (0) |

| Surgeries | 8 (47) |

| Bisphosphonate (oral) | 1 (6) |

| Bisphosphonate (i.v.) | 5 (29) |

| Interferon | 0 (0) |

N is the number of patients who received ≥1 dose of denosumab.

One patient discontinued the study and denosumab treatment due to disease progression. For the 17 patients, median time in the study was 13.1 (range, 8.9–17.9) months.

The proportion of patients with an objective tumor response (primary end point) was 88% (15/17) based on best response using any tumor response criteria (Table 3). The proportion of patients with an objective tumor response using individual response criteria was 35% (6/17) based on modified RECIST, 82% (14/17) based on modified EORTC criteria, and 71% (12/17) based on inverse Choi criteria (density/size). The median time to an objective tumor response was 3.0 months (95% CI 2.9–3.1) based on best response using any tumor response criteria. The Kaplan–Meier curve for time to objective response based on best response is shown in supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. The Kaplan–Meier estimates showed that the proportion of patients achieving an objective tumor response based on best response was 82% at week 25 and 88% at week 49. Of 15 patients with an objective tumor response, 1 patient had PD following an objective tumor response based on best response evaluation.

Table 3.

Proportion of patients with an objective tumor response

| Objective tumor response (OTR) |

Median time to OTRa | OTR sustained ≥24 weeks | Tumor control sustained ≥24 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude incidence n/N1 (%) |

95% CIb | Months (95% CI) | n/N2 (%) | n/N2 (%) | |

| Based on best response | 15/17 (88) | 64–99 | 3.0 (2.9–3.1) | 13/15 (87) | 15/15 (100) |

| Modified RECIST ver.1.1 | 6/17 (35) | 14–62 | NE (8.5–NE) | 3/15 (20) | 15/15 (100) |

| Modified EORTC (18F-FDG–PET) | 14/17 (82) | 57–96 | 3.1 (2.9–8.6) | 8/15 (53) | 14/15 (93) |

| Modified inverse Choi (density/size) | 12/17 (71) | 44–90 | 3.1 (2.9–NE) | 10/15 (67) | 15/15 (100) |

N1 is the number of patients with at least one evaluable time point assessment using the respective tumor response criterion. N2 is the number of subjects with at least two evaluable time point assessments that were at least 24 weeks apart using the respective tumor response criteria.

aKaplan–Meier estimate.

bExact confidence interval.

NE, not estimable; OTR, objective tumor response = CR + PR; tumor control = CR + PR + SD.

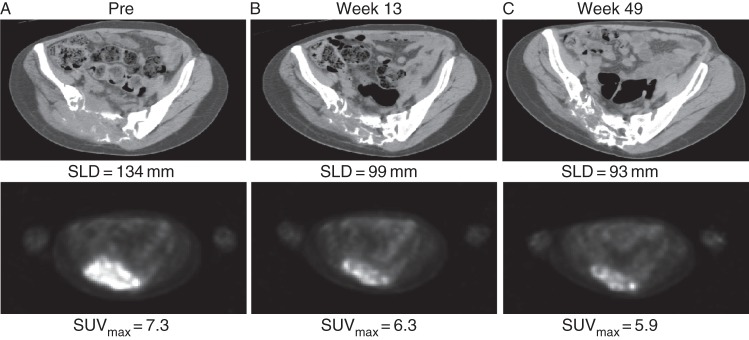

The objective tumor response was sustained for at least 24 weeks in 87% (13/15) of patients. By response category, 24% (4/17) had CR, 65% (11/17) had PR, and 12% (2/17) had SD based on best response using any tumor response criteria. All CR were based on EORTC criteria. Figure 1 shows a typical example of tumor size reduction and bone formation after denosumab treatment. Four patients had surgically resectable GCTB (two patients, primary resectable; two patients, recurrent resectable). None of these four patients had undergone surgery as of the data cutoff date. Three of these four patients had PR based on best response using any tumor response criteria. One patient had SD based on best response using any tumor response criteria.

Figure 1.

CT and PET of sacral GCTB pre- and post-denosumab treatment. A 30-year-old female with recurrent unresectable GCTB of the sacrum. SLD, sum of the lesion diameters; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value.

Clinical benefits (e.g. pain reduction, improved mobility, and improved function) of denosumab treatment, as determined by investigators, were reported in 82% of patients (14/17). Of 15 patients with an objective tumor response, 12 patients had investigator-determined clinical benefits. Of 2 patients without an objective tumor response, 2 patients had investigator-determined clinical benefits. Denosumab treatment resulted in rapid pain improvement. At least 50% of patients who had a worst pain score of ≥2 at baseline reported clinically meaningful reduction (i.e. ≥2-point decrease from baseline) in worst pain at week 5 and at all subsequent evaluations. For investigator-reported disease status with best post-baseline response, 0% had CR, 82% (14/17) had PR, 18% (3/17) had SD, and 0% had PD.

The levels of urinary N-telopeptide corrected for urine creatinine (uNTX/Cr) and serum type 1 C-telopeptide (CTX1) were consistently suppressed from week 5 onward. Median percent changes from baseline in uNTX/Cr and serum CTX1 concentrations at week 5 were −74% and −62%, respectively (supplementary Figures S2–S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The mean trough serum denosumab concentrations at the end of the loading dose period (week 5) were ∼2.5-fold higher than those following the first dose (day 8), and remained stable thereafter during the 4-weekly dosing period (supplementary Figure S7, available at Annals of Oncology online). Between weeks 9 and 49, the mean trough levels varied by <18%, which indicates that denosumab pharmacokinetics did not change over time or with multiple dosing.

All 17 enrolled patients experienced at least one adverse event. The adverse events (reported in ≥2 patients) and treatment-related adverse events (reported in ≥2 patients) are shown in Table 4. The incidence of patients with adverse events of CTCAE grade 3 or higher was 24% (4/17). These adverse events were grade 3 pneumothorax (two patients), grade 3 pain (one patient) and grade 3 glioblastoma (one patient), and were all reported by investigators as serious adverse events. Both patients with serious adverse events of pneumothorax had lung metastasis. Serious adverse events considered by the investigator to be related to the investigational product were reported for one patient (pneumothorax). No deaths were reported during the study. No patients had adverse events leading to discontinuation of denosumab or withdrawal from the study; a single patient withdrew from the study due to disease progression. None of the patients tested positive for the development of anti-denosumab antibodies. No new safety risk associated with denosumab was identified after medical review.

Table 4.

Summary of adverse events

| All patients (N = 17) | |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Any adverse event | 17 (100) |

| Adverse events reported in ≥2 patients | |

| Nasopharyngitis | 5 (29) |

| Dental caries | 4 (24) |

| Influenza | 4 (24) |

| Injection site reaction | 4 (24) |

| Malaise | 4 (24) |

| Nausea | 3 (18) |

| Pyrexia | 3 (18) |

| Arthralgia | 2 (12) |

| Cystitis | 2 (12) |

| Headache | 2 (12) |

| Periodontitis | 2 (12) |

| Pneumothorax | 2 (12) |

| Toothache | 2 (12) |

| Any treatment-related adverse events | 12 (71) |

| Treatment-related adverse events reported in ≥2 subjects | |

| Injection site reaction | 4 (24) |

| Pyrexia | 3 (18) |

| Malaise | 2 (12) |

| Periodontitis | 2 (12) |

| CTCAE grade 3 or higher adverse events | 4 (24) |

| Serious adverse events | 4 (24) |

| Adverse event of interesta | |

| Hypocalcaemia | 1 (6) |

| Adjudicated positive ONJ | 0 (0) |

| Potentially associated with hypersensitivity | 3 (18) |

| Infection | 11 (65) |

| New primary malignancy | 1 (6) |

| Cardiac disorders | 0 (0) |

| Vascular disorders | 1 (6) |

N is the number of patients who received ≥1 dose of the investigational product. n is the Number of patients reporting ≥1 event.

a‘Adverse events of interest’ have been defined in previous studies of denosumab.

Includes only treatment-emergent adverse events and serious adverse events. Coded using MedDRA version 15.1 by preferred term search strategy or SMQ.

discussion

Rapid and sustained effects have been observed in patients with GCTB after treatment with denosumab. There are no well-established tumor response criteria for subjects with GCTB. Chawla et al. [9] reported the results of a retrospective independent imaging assessment of the response of GCTB to denosumab. We report, for the first time, results from a prospective independent imaging assessment of the response of GCTB to denosumab. Chawla et al. evaluated radiological images in a standard-of-care setting, whereas we evaluated radiological images (CT/MRI, PET/PET–CT) at scheduled visits. In our study, we adopted the same response assessment criteria as used by Chawla et al. Eighty-eight percent of patients had an objective tumor response in this study. The median time to an objective tumor response was 3 months. The objective tumor response was sustained for at least 24 weeks in 87% of patients. The results of each objective tumor response in our study were similar to those in the study by Chawla et al. These findings show that denosumab has a robust antitumor effect on GCTB. It is also suggested that evaluation of tumor response using RECIST may not completely describe the effects of therapy on GCTB.

One patient was evaluated as having PD following an objective tumor response based on the best response evaluation. For that patient, a new lesion (glioblastoma) was identified by MRI. Based on the investigator's assessment, the patient was judged not to have PD, because the patient had an adverse event of glioblastoma as a new primary malignancy based on the results of biopsy.

Limitations of this study are the single-arm study design and not being a placebo-control study. To minimize these limitations, we conducted an independent review of images. The results are consistent with investigator-reported disease status.

Trough serum denosumab concentrations indicated that the loading dose regimen increased the systemic exposure to target levels as anticipated. The mean trough serum levels of denosumab in this study were comparable with those previously determined in other studies using the same dosage [8].

Denosumab was generally well tolerated in Japanese patients with GCTB. The safety profile of denosumab was consistent with that previously observed with denosumab at this dose level [8, 9].

Before the availability of denosumab, patients with surgically unsalvageable GCTB had no treatment options that had been shown to provide a durable therapeutic response. Bisphosphonates have been used to treat unresectable GCTB [12]. Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and osteoclast formation and are active against osteoclast-like giant cells. However, historical data on the outcome of this treatment are limited. Of the bisphosphonate that is absorbed (via oral preparation) or infused (via i.v. administration), ∼50% is excreted unaltered by the kidney. The remaining nonexcreted drug has a very high affinity for bone tissue and is rapidly adsorbed on to the bone surface [13]. However, there is little bony structure in GCTB lesions. This lack of adsorption may limit the efficacy of bisphosphonates. On the other hand, the serum denosumab concentration was maintained during the study. It may have a sustained effect on GCTB.

Denosumab is assumed to control disease progression in patients with unresectable GCTB. However, there is no current evidence on treatment after response, and how long denosumab treatment should be continued in unresectable patients has not been determined. Whether denosumab can reduce the recurrence rates following definitive surgery also remains unclear. Further investigation of the long-term use of denosumab and collection of clinical experience are mandatory.

funding

This work was supported by Daiichi Sankyo. No grant number is applicable.

disclosure

TU received payment for consultation from Daiichi Sankyo, payment for participation in an advisory board from Amgen, contract research funding from Eisai, GSK, MSD, and Taiho, and honoraria from GSK and Taiho. HM received contract research funding from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, GSK, and Taiho. YN, HT, and YM received contract research funding from Daiichi Sankyo. SK received payment for contract research funding from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, GSK, MSD, and Taiho. YA is employee of Daiichi Sankyo and owns Daiichi Sankyo stock. TI is employee of Daiichi Sankyo. TY received payment for consultation from Daiichi Sankyo.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating patients, their families, and staff at the study site. The authors also acknowledge the assistance of Amgen for editorial assistance with the manuscript.

references

- 1.Szendröi M. Giant-cell tumour of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86B: 5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malawer M, Helman L, O'Sullivan B. Sarcomas of bone. In Cancer: Principles and Practices of Oncology, 8th edition Philidelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2008; 1794–1834. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbeitsgemeinschaft Knochentumoren, Becker WT, Dohle J et al. Local recurrence of giant cell tumor of bone after intralesional treatment with and without adjuvant therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90: 1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caudell JJ, Ballo MT, Zagars GK et al. Radiotherapy in the management of giant cell tumor of bone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003; 57: 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brien EW, Mirra JM, Kessler S et al. Benign giant cell tumour of bone with osteosarcomatous transformation (“dedifferentiated” primary malignant GCT): report of two cases. Skeletal Radiol 1997; 26: 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin PP, Guzel VB, Moura MF et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with giant cell tumour of the sacrum treated with selective arterial embolization. Cancer 2002; 95: 1317–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branstetter DG, Nelson SD, Manivel JC et al. Denosumab induces tumor reduction and bone formation in patients with giant-cell tumor of bone. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 4415–4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas D, Henshaw R, Skubitz K et al. Denosumab in patients with giant-cell tumour of bone: an open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chawla S, Henshaw R, Seeger L et al. Safety and efficacy of denosumab for adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumour of bone: interim analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 901–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleeland CS. Pain assessment in Cancer—Chapter 21. In Osoba D (eds), Effect of Cancer on Quality of Life. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991; 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi H, Charnsangavej C, Faria SC et al. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 1753–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tse LF, Wong KC, Kumta SM et al. Bisphosphonates reduce local recurrence in extremity giant cell tumor of bone: a case-control study. Bone 2008; 42: 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller PD. The kidney and bisphosphonates. Bone 2011; 49: 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.