Abstract

The purpose of this study was to analyze the patterns of care and outcomes of patients with FIGO Stage I/II cervical cancer who underwent definitive radiotherapy (RT) at multiple Japanese institutions. The Japanese Radiation Oncology Study Group (JROSG) performed a questionnaire-based survey of their cervical cancer patients who were treated with definitive RT between January 2000 and December 2005. A total of 667 patients were entered in this study. Although half of the patients were considered suitable for definitive RT based on the clinical features of the tumor, about one-third of the patients were prescribed RT instead of surgery because of poor medical status. The RT schedule most frequently utilized was whole-pelvic field irradiation (WP) of 30 Gy/15 fractions followed by WP with midline block of 20 Gy/10 fractions, and high-dose-rate intracavitary brachytherapy (HDR-ICBT) of 24 Gy/4 fractions prescribed at point A. Chemotherapy was administered to 306 patients (46%). The most frequent regimen contained cisplatin (CDDP). The median follow-up time for all patients was 65 months (range, 2–135 months). The 5-year overall survival (OS), pelvic control (PC) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates for all patients were 78%, 90% and 69%, respectively. Tumor diameter and nodal status were significant prognostic indicators for OS, PC and DFS. Chemotherapy has potential for improving the OS and DFS of patients with bulky tumors, but not for non-bulky tumors. This study found that definitive RT for patients with Stage I/II cervical cancer achieved good survival outcomes.

Keywords: cervical cancer, early stage, radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Several retrospective studies have reported favorable outcomes for patients with cervical cancer who were treated with definitive radiotherapy (RT), not only for early-stage, but also for advanced-stage cancer [1–9]. One randomized clinical trial (RCT) found that there was no significant difference in the overall survival (OS) of patients treated with surgery and those treated with definitive RT [10]. After the results of that RCT, the clinical practice guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommended both surgery and definitive RT as treatment modalities for patients with resectable early-stage uterine cervical cancer [11, 12]. The RCT also found significantly poorer outcomes for patients with bulky tumor (diameter >4 cm) who underwent either surgery or definitive RT [10]. Therefore, additional treatment is thought necessary for patients with bulky tumors. Although several RCTs of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) followed by surgery versus surgery alone have been performed, none demonstrated improved survival for the NAC arm [13, 14]. Intermediate or high-risk pathological findings in the surgical specimen are indications for adjuvant treatments such as postoperative RT or concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) [11, 12]. However, increased incidence and grades of complications were reported for patients treated with surgery followed by postoperative RT [10]. On the other hand, several RCTs have demonstrated that definitive CCRT improved survival compared with RT alone [15]. The effect was significant, especially for patients with FIGO Stage I or II uterine cervical cancer [15]. Based on these findings, it seems reasonable to choose definitive RT or CCRT as the first treatment, except for some surgical cases who would not need adjuvant RT/CCRT.

The Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) have periodically conducted a nationwide clinical practice pattern survey of uterine cervical cancer. Although the Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) guidelines have recommended either surgery or definitive RT as treatments for early-stage cervical cancer [14], the JSOG survey reported that only 7% of patients with Stage I cervical cancer and 33% of patients with Stage II disease were treated with RT or CCRT [16].

Most clinical data on RT for Stage I/II Japanese cervical cancer patients have been derived from the experience of single institutions with small numbers of patients. Additional evidence on the efficacy and safety of RT for patients with early-stage cervical cancer is needed before the use of RT for these patients will increase. In addition, there is no available information on the use of RT for patients with bulky disease, although treatment results from a prospective multicenter study of RT for non-bulky disease have recently been reported [17]. The objective of this retrospective study was to analyze the treatment outcomes of a large number of patients with early cervical cancer who were treated with RT at multiple Japanese institutions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Japanese Radiation Oncology Study Group (JROSG) sent a questionnaire-based survey to 18 institutions that treated patients with FIGO Stage I/II uterine cervical cancer between January 2000 and December 2005 using definitive RT. Data were sent back to the data center at the Department of Medical Physics and Engineering, Osaka University.

The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee affiliated with the study chair (University of the Ryukyus). The questionnaire consisted of the following items: age, FIGO stage, indications for RT, pathology, maximum tumor diameter, lymph node status, modalities used for evaluation, start and end date of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), total dose and dose per fraction of EBRT (with or without midline block), dose rate of intracavitary brachytherapy (ICBT), dose prescribing point of ICBT, total dose and dose/fraction (fr) of ICBT, chemotherapy regimen and timing of delivery (concurrent or not), starting date of chemotherapy, date of recurrence, recurrence site, and date and site of adverse effects (rectum, small intestine, bladder, other organs). The median follow-up time of all patients was 65 months (range, 2–135 months).

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to derive estimates of the OS, pelvic control (PC), and disease-free survival (DFS) rate. For all tests, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The tests for equivalence of the estimates of OS, PC and DFS consisted of the Breslow and log-rank tests. Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. Adverse effects that occurred 90 days or more from the start of treatment were defined as late complications. Late complications were classified according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) late morbidity scoring criteria [18].

RESULTS

A total of 667 patients were entered in this study. Patients treated with ICBT alone were excluded. Table 1 shows the number of patients from each institution. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the patients, focusing on the tumor. Although half of the patients were considered suitable for definitive RT, based on the features of the tumor, about one-third of the patients were prescribed RT instead of surgery because of age or poor physical condition.

Table 1.

Participating institutions

| Institution | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| National Institute of Radiological Sciences | 114 |

| University of the Ryukyus | 100 |

| Saitama Cancer Center | 72 |

| Tohoku University | 58 |

| Saga University | 52 |

| Kurume University | 45 |

| Shizuoka Cancer Center Hospital | 34 |

| Kitasato University | 31 |

| Sapporo Medical University | 27 |

| Hiroshima University | 25 |

| Kyushu University | 23 |

| Chiba University | 22 |

| Gunma University | 18 |

| Nagoya City University | 17 |

| Kansai Medical University | 10 |

| Yamagata University | 9 |

| Kobe University | 7 |

| St Marianna University | 3 |

| Total: | 667 |

Table 2.

Patient and tumor characteristics (n = 667)

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (year): 63 (range: 24–95) | ||

| FIGO stage | ||

| IA | 1 | |

| IB | 199 | 30 |

| IB1 | 122 | 18 |

| IB2 | 51 | 8 |

| IB unknown | 26 | 4 |

| IIA | 87 | 13 |

| IIB | 380 | 57 |

| Pathology | ||

| SqCC | 612 | 92 |

| Adeno + AS | 46 | 7 |

| other | 9 | 1 |

| Primary tumor diameter | ||

| median (mm): 41 (range: 3–125) | ||

| <4 cm | 262 | 39 |

| ≥4 cm | 352 | 53 |

| unmeasurable | 53 | 8 |

| 667 | ||

| Lymph node metastasisa | ||

| negative | 512 | 78 |

| positive | 145 | 22 |

| unknown | 10 | 1 |

| Indication for definitive radiotherapy: | ||

| Characteristics of the cancer | 334 | 50 |

| Unsuitable for surgery (e.g. poor physical condition) | 239 | 36 |

| Patient's decision | 47 | 7 |

| Other | 47 | 7 |

aLymph nodes ≥10 mm in minimum diameter by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. SqCC = squamous cell carcinoma, Adeno = adenocarcinoma, AS = ademosquamous carcinoma.

Table 3 summarizes the details of RT and chemotherapy. The median total dose of EBRT without a midline block (MB) was 30 Gy/15 fr (range, 0–65 Gy), and the median total dose with MB was 20 Gy/10 fr (range, 0–50.4 Gy). The median total dose of ICBT at point A was 24 Gy/4 fr (range, 5–35 Gy for high-dose-rate [HDR] and 20–54 Gy for low-dose-rate [LDR]). The median overall treatment time for RT was 47 days (range, 14–160). The most frequent chemotherapy was concurrent delivery of cisplatin (CDDP).

Table 3.

Details of radiotherapy and chemotherapy

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Radiotherapy (n = 667) | ||

| EBRT | ||

| Whole pelvic field | 622 | 94 |

| Extended field | 27 | 4 |

| Small pelvic fielda | 10 | 1 |

| Others or details not available | 8 | 1 |

| 667 | ||

| ICBT | ||

| HDR-ICBT | 637 | 95 |

| LDR-ICBT | 24 | 4 |

| No ICBT | 6 | 1 |

| Chemotherapy (n = 306) | ||

| Concurrent | 268 | 88 |

| Neoadjuvant | 18 | 6 |

| Adjuvant | 2 | |

| Intra-arterial injection | 5 | 2 |

| Details were not available | 13 | 4 |

aSmall pelvic field excluded the common iliac region. EBRT = external beam radiotherapy, ICBT = intracavitary brachytherapy, HDR = high-dose-rate, LDR = low-dose-rate.

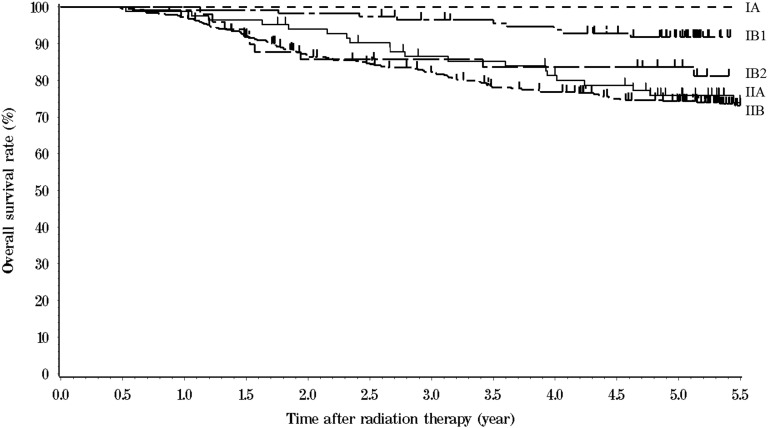

The five-year OS, PC and DFS rates for all 667 patients were 78% (95% confidence interval [CI], 75%–81%), 90% (95% CI, 88%–93%) and 69% (95% CI, 66%–73%), respectively. Mortality included 113 patients who died of cervical cancer, and 45 patients who died of other causes. Figure 1 shows the OS curves according to FIGO stage. Table 4 shows the 5-year actuarial outcomes of various tumor-related factors. Patients with adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma had significantly poorer OS and DFS than patients with squamous cell carcinoma, but there was no significant difference in PC. Patients with bulky tumor (≥4 cm) had significantly poorer OS, PC and DFS than those with non-bulky tumors. Patients with lymph node metastasis had significantly poorer OS, PC and DFS than those without nodal metastasis. Table 5 shows the 5-year actuarial outcomes according to maximum tumor size and lymph node status.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival curves of cervical cancer patients treated with definitive radiotherapy according to FIGO stage.

Table 4.

Five-year actuarial outcomes according to tumor-related factors (n = 667)

| (n) | OS (%) | PC (%) | DFS (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIGO stage | |||||

| IA | 1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| IB | 199 | ||||

| IB1 | 122 | 92 | 98 | 86 | |

| IB2 | 51 | 84 | 96 | 77 | |

| IB unknown | 26 | 65 | 91 | 61 | |

| IIA | 87 | 76 | 89 | 68 | |

| IIB | 380 | 74 | 88 | 65 | |

| P < 0.001 | P = 0.003 | P = 0.001 | |||

| Pathology | SqCC | 612 | 80 | 91 | 72 |

| Adeno + AS | 46 | 61 | 89 | 50 | |

| P = 0.001 | NS | P = 0.001 | |||

| Maximum tumor diameter | |||||

| <4 cm | 262 | 83 | 93 | 75 | |

| >4 cm | 352 | 75 | 88 | 65 | |

| P = 0.02 | P = 0.01 | P = 0.004 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||

| Negative | 512 | 82 | 92 | 75 | |

| Positive | 145 | 65 | 83 | 50 | |

| P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | |||

OS = overall survival, PC = pelvic control, DFS = disease-free survival, SqCC = squamous cell carcinoma, Adeno = adenocarcinoma, AS = adenosquamous carcinoma.

Table 5.

Five-year actuarial outcomes by tumor size/nodal status

| n | OS (%) | PC (%) | DFS (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor sizea | Nodal status | ||||

| Bulky | Positiveb | 119 | 64 | 82 | 49 |

| Bulky | Negative | 230 | 80 | 91 | 74 |

| Non-bulky | Positiveb | 23 | 68 | 90 | 56 |

| Non-bulky | Negative | 237 | 84 | 94 | 77 |

| P < 0.001 | P = 0.003 | P < 0.0001 |

OS = overall survival, PC = pelvic control, DFS = disease-free survival, aBulky = maximum tumor diameter ≥4 cm. bLymph nodes with minimum diameter ≥10 mm as measured by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

For all 667 patients, no significant differences were observed in the respective OS, PC or DFS of patients treated with RT alone or those treated with chemoradiotherapy (5-year OS: 81% vs 76%, P = 0.14; 5-year PC: 89% vs 92%, P = 0.13; 5-year DFS: 81% vs 76%, P = 0.98).

Chemotherapy was administered to 68% of patients with bulky tumors (240 of 352) and 79% of lymph node metastasis patients (114 of 145). Chemotherapy was most frequently administered to these high-risk patients concurrently with RT.

Table 6 summarizes the 5-year actuarial outcomes as a function of tumor size/nodal status and treatment. Among the patients with bulky tumors, OS and DFS were significantly better for patients treated with chemotherapy than for those who did not undergo chemotherapy, and there was no significant difference in PC between the two treatment groups. For patients with non-bulky tumors, there were no significant differences in OS, PC or DFS between the patients who were treated with CCRT and those who received RT alone.

Table 6.

Five-year actuarial outcomes as a function of tumor size/nodal status and treatment

| n | OS (%) | PC (%) | DFS (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size | |||||

| Bulky | RT | 112 | 60 | 86 | 56 |

| (≥4 cm) | CRT | 240 | 81 | 88 | 70 |

| P = 0.002 | NS | P = 0.02 | |||

| Non-bulky | RT | 206 | 83 | 94 | 76 |

| (<4 cm) | CRT | 56 | 81 | 90 | 72 |

| NS | NS | NS | |||

| Nodal status | |||||

| Positivea | RT | 31 | 43 | 77 | 36 |

| CRT | 114 | 71 | 85 | 54 | |

| P = 0.062 | NS | NS | |||

| Negative | RT | 325 | 79 | 91 | 73 |

| CRT | 187 | 87 | 93 | 80 | |

| P = 0.016 | NS | NS |

OS = overall survival, PC = pelvic control, DFS = disease-free survival, RT = radiotherapy alone, CRT = chemoradiotherapy. aLymph nodes with minimum diameter ≥10 mm as measured by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Among lymph-node–positive patients, OS was better for patients treated with chemotherapy than for those who did not undergo chemotherapy. There were no significant differences in the PC or DFS between the two treatment groups. For patients without lymph node metastasis, similar trends were observed. OS was better for patients treated with chemotherapy than for those who did not receive chemotherapy, and there were no significant differences in PC or DFS between the two treatment groups.

Table 7 summarizes the results of multivariate analysis of outcomes according to prognostic factors. Administration of chemotherapy had a significant impact on OS and DFS, but there was no significant impact on PC.

Table 7.

Multivariate analyses for outcomes according to prognostic factors

| OS (%) |

PC (%) |

DFS (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (<63 vs ≥63) | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| FIGO Stage (IB1 vs IB2 vs IIA vs IIB) | 1.4 | 1.2–1.7 | 0.0005 | 2.0 | 1.3–2.9 | 0.001 | 1.3 | 1.1–1.5 | 0.0003 |

| Pathology (SCC vs Adeno/AS) | 2.3 | 1.3–4.3 | 0.005 | NS | 2.3 | 1.4–3.9 | 0.0009 | ||

| Tumor diameter (<4 cm vs ≥4 cm) | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| Lymph node status (negative vs positive) | 2.1 | 1.4–3.1 | 0.0003 | 1.9 | 1.0–3.4 | 0.05 | 2.6 | 1.9–3.7 | <0.0001 |

| Administration of chemotherapy (no vs yes) | 0.4 | 0.3–0.6 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.6 | 0.4–0.8 | 0.0006 | ||

HR = hazards ratio, CI = confidence interval, OS = overall survival, PC = pelvic control, DFS = disease-free survival, Adeno = adenocarcinoma, AS = adenosquamous carcinoma.

Recurrence developed in 159 of 667 patients as follows: 60 patients (9%) had pelvic recurrence alone, 86 patients (13%) had distant metastases only, and 13 patients (2%) developed both pelvic recurrence and distant metastases. The most frequent site of distant metastasis was the extrapelvic lymph nodes. The rate and site of metastases to lymph nodes were as follows: 52 patients (8%) had para-aortic metastatic lymph nodes, 18 patients (3%) had scalene nodes, 12 patients (2%) had mediastinal nodes, and 4 patients (1%) had other nodes. Other sites of metastases were as follows: 35 patients (5%) had lung metastases, 16 patients (2%) had bone metastases, 5 patients (1%) had liver metastases, and 4 patients (0.6%) had brain metastases.

Late complications developed in 178 patients (27%). There were 35 patients (5%) who developed severe (Grade 3 or higher) complications. The 5-year severe complication rate was 5.5% (95% CI: 3.6%–7.9%). The details are shown in Table 8. LDR-ICBT had a significant impact on the incidence of severe complications (P = 0.036). Other factors (total dose of EBRT without MB, total dose and dose/fr HDR-ICBT, administration of chemotherapy) did not have a significant impact on the incidence of severe complications.

Table 8.

Details of late complications* (n = 667)

| Grade 1 |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

Total |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Proctitis | 63 | 9 | 30 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0.3 | 100 | 15 |

| Cystitis | 14 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.4 | 40 | 6 |

| Enterocolitis | 12 | 2 | 17 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0.3 | 39 | 6 |

| Others | 11 | 2 | 17 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 43 | 6 |

*Some patients had complications in multiple organs. Toxicity was judged by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group late morbidity scoring criteria.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study (n = 667) of patients with early cervical cancer who were treated with definitive RT, mainly with HDR-ICBT. The standard Japanese RT schedule achieved favorable survival rates and acceptable rates of complications that were comparable with previous studies [1–9].

The JSOG survey reported that the 5-year OS rates of patients with Stage I cervical cancer who were treated with surgery or RT were 93% and 80%, respectively, and the rates of Stage II patients were 81% and 74%, respectively [16]. The 5-year OS rates of our Stage I/II patients treated with RT were similar to the results of the JSOG RT group, but poorer than the results of the JSOG surgery group. Landoni et al. reported the results of their RCT, showing that the 5-year OS of Stage IB–IIA patients undergoing surgery was 83%, which was equivalent to the survival of patients undergoing definitive RT [10]. Selection bias might partially account for why the results of our study were inferior to the JSOG surgery group. The JSOG survey reported that ≥90% of Stage I patients and 67% of Stage II patients were treated with surgery [16]. It may be that the JSOG RT patients were mainly those who were unsuitable for surgery (poor general physical condition, elderly, metastatic lymph nodes). Our study might have had a similar selection bias. About one-third of our patients were elderly and/or in poor physical condition; one-third of the patients eventually died of other diseases.

A prospective study of definitive RT for patients with Stage I/II cervical cancer without bulky tumor or lymph node metastasis demonstrated an excellent 3-year PC of 96% and a 3-year OS of 95% [17]. In our study, the patients without bulky tumors and lymph node metastasis achieved good OS compared with the JSOG patients who underwent surgery. Even though they were treated with RT alone, non-bulky tumor and/or node-negative patients achieved good OS, PC and DFS. In contrast, our study patients with bulky tumors and/or lymph node metastasis had poor OS and PC. RTOG9001, a RCT of definitive CCRT, also included patients with Stage I/II cervical cancer with bulky tumors (>5 cm) and/or lymph node metastasis, as well as Stage III/IVA patients [19]. The outcomes of RTOG9001 were good for patients with Stage I/II disease treated with CCRT; the 5-year PC was 87% and the 5-year OS was 79%.

Our study patients treated with CCRT achieved PC and OS, similar to RTOG9001. We believe the fact that our outcomes were inferior to those of the JSOG patients undergoing surgery might have been accounted for by the low rate of chemotherapy administration to our patients. In our study, only 70% of patients were treated with chemotherapy, while the remaining patients did not receive chemotherapy even if they had bulky tumors and/or lymph node metastasis. This lower rate of chemotherapy treatment for high-risk patients might have adversely affected our outcomes, which were slightly worse than the JSOG surgery patients. In our study, patients with bulky tumors who were treated with chemotherapy achieved significantly better OS and DFS compared with patients who did not receive chemotherapy, and the same trend was observed for the patients with metastatic lymph nodes. Our results indicate that chemotherapy did not provide additional improvement of local control for Stage I/II patients, although OS and DFS were improved by chemotherapy. Based on these findings, although chemotherapy acts as an RT sensitizer, we think that the predominant role of chemotherapy for Stage I/II patients is to prevent distant metastases. Patients with bulky tumors and/or lymph node metastasis have been regarded as being at some risk of distant micrometastasis; therefore, we believe that it is important to administer chemotherapy if applicable. Prospective clinical trials of CCRT for Stage I/II cervical cancer patients with bulky tumors and/or lymph node metastasis are warranted. Because it is believed that patients in poor physical condition or of advanced age may be poor candidates for chemotherapy, we should also conduct trials that investigate suitable regimens for elderly patients or those in poor physical condition. Mitsuhashi et al. reported acceptable toxicity for low-dose CDDP for elderly patients [20]. Several reports have shown that nedaplatin achieved good survival with acceptable toxicity [21, 22]. We think that conducting clinical trials using similar less toxic regimens or drugs is valuable.

However, our patients with non-bulky tumors achieved good OS, PC and DFS, even though they were treated with RT alone. These findings are consistent with the results of a prospective clinical trial previously performed in Japan [17]. Taken together with our results, the findings suggest that for patients with non-bulky tumors, RT alone may be an adequate treatment for achieving good PC, OS and DFS.

Our study had some limitations. Some patients in this study had inadequate follow-up periods. This could be a critical flaw. If an adequate follow-up had been achieved for all patients, the outcomes might have changed. The JSOG's annual survey for survival analysis only includes patients from institutions with follow-up rates of >80% for treated patients [16]. A national cancer registration system that can achieve an adequate follow-up should be developed. Another limitation was on the types of data collected in this study. Unfortunately, we minimized the numbers of survey items to reduce the workload of our collaborators.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that definitive RT for patients with Stage I/II cervical cancer achieved excellent PC. The results indicate that definitive RT can be considered the treatment of choice for patients with early-stage cervical cancer. However, it was difficult to compare the survival outcomes of our series directly with the outcomes from surgical series because of the diversity of patient backgrounds in our series. Prospective studies of definitive CCRT for patients with bulky tumors and/or lymph node metastasis are warranted. Moreover, for appropriate outcome reports, we suggest that a national database of patients treated with RT in Japan should be developed.

FUNDING

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charge for this article was provided by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research A (No. 21249066) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT); and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (No. 60158194); the National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds (23-A-21, 26-A-4 and 26-A-28) Japan.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank members of the Japan Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (JROSG) for their support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nakano T, Kato S, Ohno T, et al. Long-term results of high-dose rate intracavitary brachytherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer 2005;103:92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong FC, Tung SY, Leung TW, et al. Treatment results of high-dose-rate remote afterloading brachytherapy for cervical cancer and retrospective comparison of two regimens. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003;55:1254–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang CJ, Leung SW, Chen HC, et al. High-dose-rate intracavitary brachytherapy (HDR-IC) in treatment of cervical carcinoma: 5-year results and implication of increased low-grade rectal complication on initiation of an HDR-IC fractionation scheme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997;38:391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Souhami L, Corns R, Duclos M, et al. Long-term results of high-dose rate brachytherapy in cervix cancer using a small number of fractions. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:508–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petereit DG, Sarkaria JN, Potter DM, et al. High-dose-rate versus low-dose-rate brachytherapy in the treatment of cervical cancer: analysis of tumor recurrence—the University of Wisconsin experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;45:1267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SW, Suh CO, Chung EJ, et al. Dose optimization of fractionated external radiation and high-dose-rate intracavitary brachytherapy for FIGO stage IB uterine cervical carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;52:1338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teshima T, Inoue T, Ikeda H, et al. High-dose rate and low-dose rate intracavitary therapy for carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Final results of Osaka University Hospital. Cancer 1993;72:2409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hareyama M, Sakata K, Oouchi A, et al. High-dose-rate versus low-dose-rate intracavitary therapy for carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a randomized trial. Cancer 2002;94:117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anker CJ, Cachoeira CV, Boucher KM, et al. Does the entire uterus need to be treated in cancer of the cervix? Role of adaptive brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;76:704–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landoni F, Maneo A, Colombo A, et al. Randomised study of radical surgery versus radiotherapy for stage Ib–IIa cervical cancer. Lancet 1997;350:535–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology – Cervical Cancer v.1.2015. National Comprehensive Cancer Network http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical.pdf (11 August 2014, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Saito T, Saito T, Suzuki N, et al. Chapter 3. Stage IB and II disease. In: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (eds). Treatment Guidelines for Uterine Cervical Cancer, 2011 edition Tokyo: Kanehara & Co. Ltd, 2011, 54–88 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Parmar MK. Can the published data tell us about the effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced cancer of the uterine cervix? Eur J Cancer 1999;35:406–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsumata N, Yoshikawa H, Kobayashi H, et al. Phase III randomised controlled trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical surgery vs radical surgery alone for stages IB2, IIA2, and IIB cervical cancer: a Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial (JCOG 0102). Br J Cancer 2013;108:1957–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vale C, Tierney JF, Stewart LA, et al. Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5802–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aoki Y. The Treatment Annual Report in 2005. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Jpn 2013;65:1147–208. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toita T, Kato S, Niibe Y, et al. Prospective multi-institutional study of definitive radiotherapy with high-dose-rate intracavitary brachytherapy in patients with nonbulky (<4-cm) stage I and II uterine cervical cancer (JAROG0401/JROSG04–2). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:e49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995;31:1341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eifel PJ, Winter K, Morris M, et al. Pelvic irradiation with concurrent chemotherapy versus pelvic and para-aortic irradiation for high-risk cervical cancer: an update of radiation therapy oncology group trial (RTOG) 90-01. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:872–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitsuhashi A, Uno T, Usui H, et al. Daily low-dose cisplatin-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with uterine cervical cancer with emphasis on elderly patients: a phase 2 trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013;23:1453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niibe Y, Tsunoda S, Jobo T, et al. Phase II study of radiation therapy combined with weekly nedaplatin in locally advanced uterine cervical carcinoma (LAUCC): Kitasato Gynecologic Radiation Oncology Group (KGROG 0501)—initial analysis. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2008;29:222–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mabuchi S, Ugaki H, Isohashi F, et al. Concurrent weekly nedaplatin, external beam radiotherapy and high-dose-rate brachytherapy in patients with FIGO stage IIIb cervical cancer: a comparison with a cohort treated by radiotherapy alone. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2010;69:224–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]