Abstract

The assumption has become that memory for words’ sound patterns, or form, is rapidly lost in comparison to content. Memory for form is also assumed to be verbatim rather than schematic. Oral story-telling traditions suggest otherwise. The present experiment investigated if form can be remembered schematically in spoken poetry, a context in which form is important. We also explored if sleep could help preserve memory for form. We tested whether alliterative sound patterns could cue memory for poetry lines both immediately and after a delay of 12 hours that did or did not include sleep. Twelve alliterative poetry lines were modified into same alliteration, different alliteration, and no alliteration paraphrases. We predicted that memory for original poetry lines would be less accurate after 12 hours, same alliteration paraphrases would be falsely recognized as originals more often after 12 hours, and that the no-sleep group would make more errors. Different alliteration and no alliteration paraphrases were not expected to share this effect due to schematically different sound patterns. Our data support these hypotheses and provide evidence that memory for form is schematic in nature, retained in contexts in which form matters, and that sleep may help preserve memory for sound patterns.

Keywords: Memory, sound patterns, form, poetry, oral traditions

1. INTRODUCTION

Poems and songs often emphasize the sound patterns, or form, of words. Across centuries and cultures, stories have been transformed into poems and songs that are subsequently memorized and passed on without the aid of written references. One explanation of this remarkable feat of memory is that sound patterns provide salient organizational frameworks for lyrical material (Rubin, 1995). When portions of a lyrical piece are forgotten, form-based structures may serve as reference points to cue memory.

Serial recall theory proposes that earlier poetry lines’ form can cue the recall of later lines (Rubin, 1995). The constraints imposed by a poem's sound pattern can help restrict appropriate choices and streamline recall as well. Unlike meaning cues (Rubin, 1995), form cues can activate an abundance of alternatives if an original item is forgotten, as in the tip of the tongue phenomenon. Memory for meaning is essential to language, but it is susceptible to interference from synonyms and alternate meanings (Rubin, 1995). Form-based memory cues are more resilient to interference, although they may only apply in contexts in which sound patterns are salient, as poetry and song.

New evidence for memory for form is emerging. Early experiments suggest that form is quickly forgotten (Bransford & Franks, 1971; Brewer & Hay, 1984), while more recent work (Lea, Rapp, Elfenbein, Mitchel, & Romine, 2008; Rapp & Samuel, 2002; Rubin, 1995; Tillman & Dowling, 2007) suggests that form is remembered in certain circumstances. For one, prominent sound patterns are more likely to be remembered, as in rhyme or alliteration. Memory for form is also not verbatim but schematic. Schemas form connections between what would otherwise be random bits of information. These summaries of knowledge can facilitate recall by providing organization for memory, as information that matches a schema is remembered better than information that does not (Anderson & Pichert, 1978; Brewer & Treyens, 1981). Importantly, schemas also allow inferences to be made about information that is forgotten. This fits with how Rubin (1995) theorized memory for form operates in oral traditions. If words are forgotten, form-based schemas can serve as cues to aid memory.

It is difficult to separate memory for meaning and memory for form in language. Rubin (1995) argued that there are schemas for meaning and schemas for form, both of which can facilitate recall for material. This is supported by work on memory for text that suggests meaning and form are remembered differently. Bransford & Franks (1971) found that participants tended to falsely remember separate sentences as being presented as one when the information within them logically followed. In this case, memory for meaning overrode memory for form. Brewer & Hay (1984) found that sentence content was remembered while stylistic form (e.g., business writing style) was not, suggesting again that memory for form is poor relative to memory for meaning. However, these experiments did not use sentences that emphasized form or made use or rhythmic sound patterns. Meaning and form likely interact as well. Rapp & Samuel (2002) found that spontaneous sentence completions were influenced by form, and in tandem with restricted semantic choices, their findings implied that form had an effect on lexical selection.

If form can influence language production, then it follows that form can influence recall as well. Production itself involves memory retrieval. However, it is crucial to consider context and the type of information that is assigned importance. Very young children (aged 2–5) can write coherent stories, likely because they are children accustomed to attending to meaning (Dowker, 1989). Even so, these same children wrote poems that contained rhyming and alliterating strings of nonsense words. This suggests an intuitive understanding that form is more important than meaning in poetry. Indeed, errors in songs and poems tend to preserve form at the expense of meaning (Rubin, 1995), which is a reversal of Bransford & Frank's (1971) and Brewer & Hay's (1984) argument that meaning is remembered over form. However, memory for form may depend on circumstances in addition to context. Rummer & Engelkamp (2001) found that auditory presentation improved verbatim short-term recall of sentences whereas visual presentation did not. Although the sentences they used were not lyrical, these findings still imply that hearing words rather than silently reading them may be essential for sound patterns to be remembered. Rogers (1970) also found that alliteration had no effect on sentence retention unless the sound pattern was emphasized through capitalization or pointed out in instructions. Despite the use of visual presentation rather than auditory presentation, these findings suggest that alliterative patterns have to be explicitly attended to in order to have an effect on memory. Thus, memory for form is unique in that it is dependent on context, auditory presentation, and salience.

Additional evidence supports this idea. Lea, Rapp, Elfenbein, Mitchel, & Romine (2008) examined the potential effects of form on memory for poetry. Participants read alliterative poems aloud and cue lines were scattered in the blocks of text. The cue lines ended in target words that were followed by recognition probes for these targets. In the recognition probes, the cue lines were altered to fit same alliteration (e.g., w- throughout), different alliteration (e.g., w- for half the line and r- for the other half), or no alliteration formats. Participants were significantly faster at remembering target words in the same alliteration condition, making it the most successful memory cue. There was no difference between the different alliteration and no alliteration conditions; in both, reaction time to recognition probes was approximately 85 milliseconds slower than the same alliteration condition on average. These findings strongly imply that form can aid memory, as phonologically similar sound patterns facilitated retrieval, presumably by acting as memory cues.

Tillman & Dowling (2007) also investigated memory for form by comparing recall for short stories and rhyming poems. Participants listened to the pieces then took recognition tests after delays ranging from approximately 9 seconds (short) to 20–30 seconds (long). Participants were instructed to identify original lines on these tests, but paraphrases that changed word order while preserving rhyme and meaning-changed lines were also presented as decoys. Participants were better at correctly distinguishing original lines from paraphrases and meaning-changed lines in the poetry condition over time. However, memory for poetry was poor in the short delay condition, while memory for prose started out strong and then decayed. This aspect of the data was not discussed, but overall these findings suggest that memory for poetry can be stable over time, even if it is not remembered as well as prose from the outset. The results of the longer delay can be taken as evidence that form was being used as a memory aid in the poetry condition. Interestingly as well, Tillman & Dowling's (2007) findings mirror Bransford & Franks’ (1971) insofar as memory for poetry was initially poor in comparison to memory for prose. Memory for poetry did not decay as sharply as memory for prose over time, however. Long-term memory for form remains largely unexplored in terms of delays lasting longer than a minute.

Increasing experimental evidence supports the theory that sleep is essential to the long-term retention of perceptual and linguistic information as well. For example, Karni and colleagues (1994) investigated performance on a visual task before and after sleep. Participants were taught to pick out target textures from background textures, and their performance on this task failed to improve if they did not enter REM sleep 8 to 10 hours later. In contrast, performance improved in participants who did enter REM sleep 8 to 10 hours after learning the task. The authors theorized that deprivation of REM sleep interfered with successful learning of the task, which in turn prevented improvement. Although the stimuli were visual, these results suggest that sleep has potential to aid in the retention of novel perceptual material.

Sleep may improve memory for auditory material as well. When a novel spoken word is incorporated into an existing vocabulary and inhibits similar words during recall, the word is said to be lexicalized. Dumay & Gaskell (2005) investigated whether novel spoken words inhibited similar words immediately, 24 hours later, and one week later. There was no evidence of lexicalization in the immediate condition. However, novel words did inhibit similar words in the 24-hour and one week conditions. Presumably, sleep had taken place in the longer interval conditions, and consequently, the authors suspected that sleep played a role in the process of lexicalization. In order to explore this issue further, Dumay & Gaskell (2007) conducted another experiment in which participants learned novel spoken words. This time they were tested for lexicalization effects immediately, 12 hours later with or without sleep, and 24 hours later. As before, the authors found that novel spoken words did not immediately inhibit similar words, which indicated that the information had not yet been lexicalized. The same pattern was found after 12 hours without sleep. However, novel words did inhibit similar words after 12 hour or 24 hour periods that included sleep.

This indicates that novel spoken words were lexicalized only after a considerable amount of time had passed and sleep had taken place. Maquet (2001) offered an explanation for this in his argument that REM sleep is essential to maintaining plasticity in the brain. Plasticity allows newly formed neural connections to strengthen, which could facilitate processes like lexicalization and visual learning during sleep (Dumay & Gaskell, 2007; Karni et al., 1994). Because sleep can influence other perceptual learning tasks, it follows that sleep could influence memory for auditory information.

The present experiment was an attempt to fill in several gaps in the literature on memory for form: 1) Is form remembered immediately and over the long-term when it is an important part of the material, as in poetry; 2) Is memory for form stable after a delay that includes sleep in comparison to an equivalent delay without sleep; 3) Is form remembered schematically—will errors favor sound patterns that are similar to originals? We investigated these questions by comparing immediate and long-term (12 hour delay) memory for alliterative poetry lines in sleep and no-sleep conditions. We hypothesized the following: 1) Recognition of original lines would be less accurate after 12 hours; 2) Accuracy would be lower in the no-sleep group than the sleep group; 3) Form-based schematic errors will increase after the 12 hour delay, meaning similar alliteration paraphrases will be mistaken for originals more often; 4) The no-sleep group will make form-based schematic errors more often than the sleep group.

2. METHODS

2.1 Norming

Forty-two Bowling Green State University undergraduates participated in an online stimuli norming survey presented via Survey Gizmo 3.0. Participants were required to be at least 18 years old and native English speakers. They were awarded course credit for participation. The sample was 76 percent female and 88 percent white, and the average age was 19 years. Five people were excluded for incorrectly answering a question that assessed if they were paying attention.

Participants rated 36 poetry line pairs for clarity and poetics using Likert scales ranging from 0 to 5. Clarity was defined as how easy the lines were to understand, and poetics was defined as how well the lines resembled poetry as opposed to ordinary sentences. A score of 0 on the Likert scales was labeled as Not Clear or Not Poetic, whereas a score of 5 was labeled as Very Clear or Very Poetic. All line pairs were rated for both qualities, and participants were also provided with a comment box in which to type any words they did not understand. The 12 line pairs with the highest average ratings were selected for use in the experiment (Clarity M = 4.2, SD = .17; Poetics M = 3.4, SD = .33). None of the 12 selected lines had any reported instances of unrecognized words. The line pairs contained a wide variation of alliterative consonants and semantic topics as well in order to minimize potential confusion amongst the lines.

2.2 Participants

Fifty-one Bowling Green State University graduate and undergraduate students participated in the experiment for either course credit or $10. They were recruited through the university's online system, email advertisements, and flyers. Participants were required to be 18 or older and native English speakers. The sample was 43 percent female, 75 percent white, and the average age was 21 years. Eleven participants were disqualified in total: three did not attend the second session, three no-sleep group participants slept, three guessed more than three times on the author recognition questionnaire, and two had a comprehension score at or below 60 percent. The purpose cut-offs was to exclude participants who showed evidence of poor attention to instructions or stimuli.

2.3 Materials

The poetry lines we used were adapted from Seamus Heaney's modern English translation of Beowulf (2001). We chose to use alliterative poetry lines because Rubin (1995) suggested that words’ initial sounds provided stronger memory cues than ending sounds. The poetry lines occasionally required minor changes in order to fit experimental conditions. All lines were transformed into two-line pairs, and outdated terms were replaced with modern terms as needed. Same alliteration paraphrases, different alliteration paraphrases, and no alliteration paraphrases were created from original lines as well. Below are examples of each:

Alliterative original line pair, adapted from Heaney (p. 213):

“They let the ground keep the gold under the gravel, gone to the earth.”

The same alliteration paraphrase keeps the original consonants intact:

“They let the grasses keep the gems under the grime, given to the earth.”

The different alliteration paraphrase that changes the alliterative consonants:

“They let the dirt keep the diamonds under the dust, dropped to the earth.”

The no alliteration paraphrase:

“They let the soil keep the riches under the mud, lost to the earth.”

Forty-eight poetry line pairs and paraphrases were included in total and divided into four lists (A, B, C, and D), each of which had three original line pairs and three of every paraphrase type included. No line pair was presented twice in any version on the same list. Participants saw different lists on their first and second sessions and list order was counterbalanced.

It is important to note that meaning was held constant across phrase types; only the surface form differed across line pairs. Alliterative synonyms were matched as closely as possible to original words for familiarity, frequency of use, and number of syllables using Coltheart's (1981) psycholinguistic database (see Appendix for a complete list of stimuli).

Participants also completed questionnaires that collected information on age, gender, ethnic background, class year, fluency in languages other than English, hours slept the night before, and whether participants slept between the first and second sessions. Participants were also asked if they were familiar with the poem Beowulf, if they dreamt (an erratic possible indicator of REM sleep), and if they liked poetry in general; however, these factors did not have meaningful significant effects and will not be discussed further. At the end of the experiment, participants completed a True/False comprehension questionnaire that pertained to basic themes in the poetry lines and assessed attention. Participants completed reading habits and author recognition questionnaires adapted from Acheson and colleagues (2008) in order to assess reading ability.

2.4 Procedure

The experiment was presented in two sessions and participants were assigned to sleep or no-sleep groups. Participants in the sleep group came in for the first session in the evening and the second session the following morning. Participants in the no-sleep group completed testing in the same day with the first session in the morning and the second session in the evening. Testing sessions were always 12 hours apart at 9, 10, or 11am/pm time slots. All participants were tested individually.

At the beginning of the first session, participants silently read a short synopsis of events in Beowulf. The synopsis was intended to alleviate confusion since poetry line stimuli were presented in random order. After the synopsis, participants completed a learning phase in which they read the 12 original line pairs aloud from a computer screen. This process was repeated three times, and an experimenter was always in the room to ensure that participants were reading aloud. The learning phase was followed by an immediate recognition test. Participants saw one of four different lists containing an equal mixture of randomly ordered original line pairs, same alliteration paraphrases, different alliteration paraphrases, and no alliteration paraphrases. Participants used Likert scales to rate how well the line pairs matched originals from the learning phase. The Likert scales ranged from 0 to 5; 0 was labeled as Definitely Not an original line pair while 5 was labeled as Definitely Yes an original line pair. As with the learning phase, the recognition items were read aloud in order to make the sound pattern as salient as possible. The first session ended once the immediate recognition test was complete. Participants returned to the lab 12 hours later for the second session and immediately took a delayed recognition test. The delayed recognition test always used a different list than the immediate recognition test. Lastly, participants filled out a general information questionnaire, comprehension questionnaire, reading habits questionnaire, and author recognition questionnaire.

3. RESULTS

The poetry lines’ Likert scale ratings were transformed into hit rates for original lines and false alarm rates for paraphrased lines. The scales were divided into Yes (3–5) or No (0–2) responses in order to calculate these proportions. Responses to original line pairs were classified as hits (Yes) or misses (No), whereas paraphrase responses were classified as false alarms (Yes) or correct rejections (No). To avoid redundancy, only hit rates and false alarm rates are reported

Item reliability analyses were conducted to ensure that no individual items(s) were carrying effects. All 48 items were within two standard deviations from the raw score rating grand mean. Error rates were comparable across conditions and lists (M = 15 percent). Four items had error rates between 40–50 percent and accounted for 9 percent of the data; three were original line pairs and one was a no alliteration line pair. It is to be expected that some lines would be more memorable than others on average, and therefore all 48 items were included in further analyses. Subjects and items were also assessed as random factors. The minF’ statistic was significant (p < 0.0001), which strongly indicates that both subject and item results are generalizable. Table 1 provides recognition proportions for original line pairs (hit rates) and same, different, and no alliteration paraphrases (false alarms) by group and delay type.

Table 1.

Proportions of Hits (Original Lines) and False Alarms (Alliteration Paraphrases)

| Overall Immediate | Overall Delayed | Sleep Immediate | Sleep Delayed | No-Sleep Immediate | No-Sleep Delayed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line Types | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Original | 0.84 (0.24) | 0.63 (0.36) | 0.80 (0.27) | 0.72 (0.38) | 0.87 (0.20) | 0.53 (0.31) |

| Same Alliteration | 0.04 (0.12) | 0.12 (0.21) | 0.05 (0.12) | 0.08 (0.15) | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.15 (0.25) |

| Different Alliteration | 0.10 (0.19) | 0.11 (0.23) | 0.12 (0.20) | 0.07 (0.14) | 0.08 (0.18) | 0.15 (0.30) |

| No Alliteration | 0.12 (0.18) | 0.15 (0.25) | 0.13 (0.20) | 0.10 (0.19) | 0.10 (0.16) | 0.20 (0.29) |

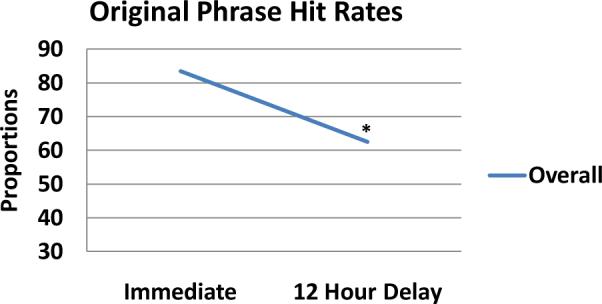

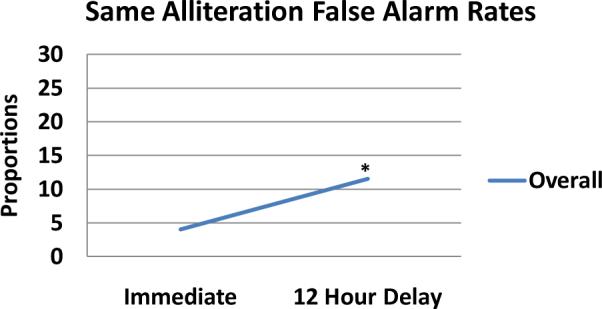

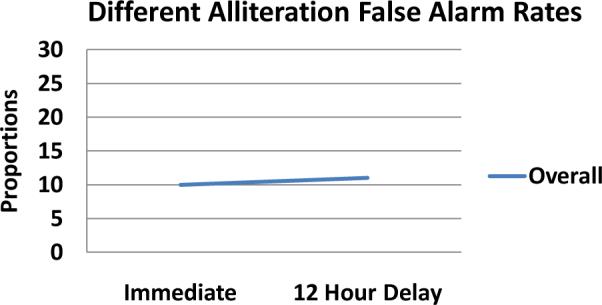

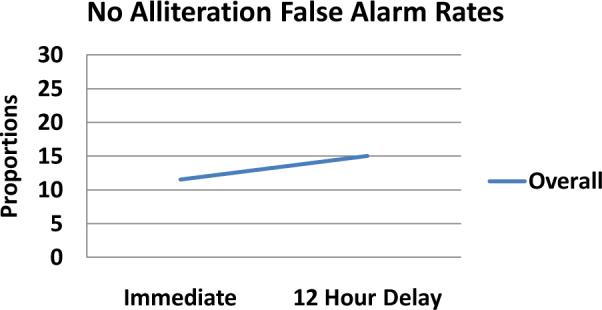

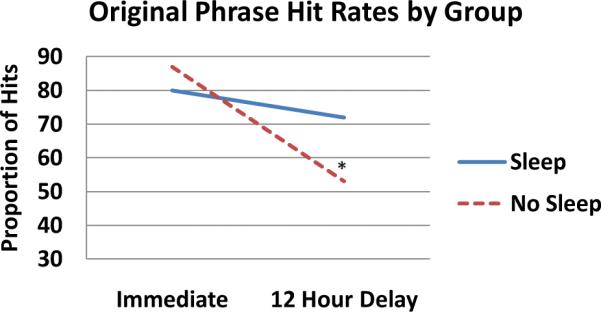

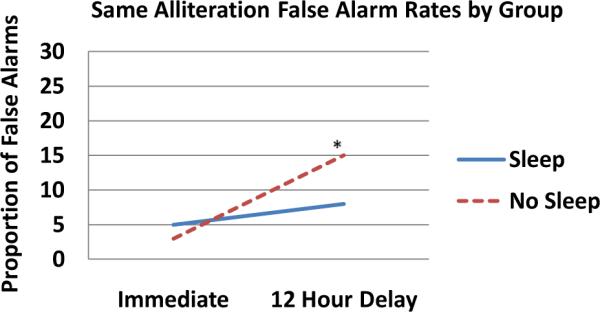

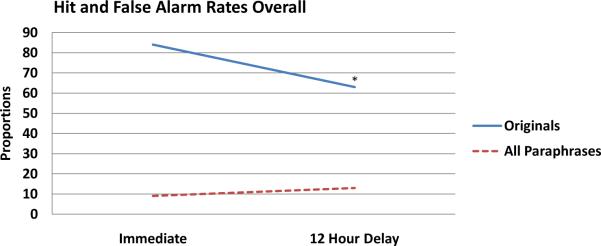

Hit rates and false alarm rates were analyzed using 2X4X2 mixed-design analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Independent variables were delay type (within subjects: immediate or 12 hour), phrase type (within subjects: original, same alliteration, different alliteration, or no alliteration), and group type (between subjects: sleep or no sleep). Overall, there was a significant effect of delay type on hit rates for original lines (F(1, 38) = 17.40, p < 0.0001). Original lines were correctly recognized more often immediately (hit rate = 84 percent) than after the 12 hour delay (hit rate = 63 percent; see Figure 1). There was also a significant effect of delay type on false alarm rates for same alliteration paraphrases (F(1, 38) = 5.71, p = 0.022). Same alliteration paraphrases were rarely mistaken for originals immediately (false alarm rate = 4 percent), but they were much more likely to be falsely recognized after the delay (false alarm rate = 12 percent; see Figure 2). As expected, there were no significant effects for different alliteration (F(1, 38) = 0.014, p = 0.91; see Figure 3) or no alliteration paraphrases (F(1, 38) = 0.28, p = 0.60; see Figure 4) overall. Original sound patterns were altered or removed in the different and no alliteration paraphrases, respectively.

Figure 1.

Original Phrase Hit Rates

Note. * Indicates significance at a p = .05 level or less.

Figure 2.

Same Alliteration False Alarm Rates

Note. * Indicates significance at a p = .05 level or less.

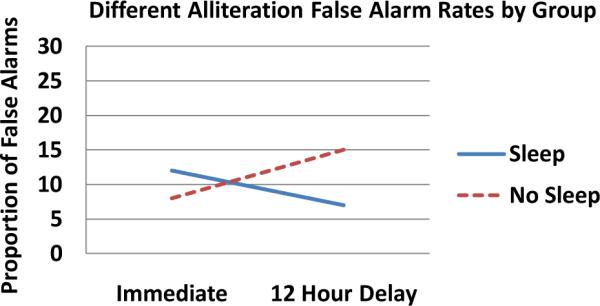

Figure 3.

Different Alliteration False Alarm Rates

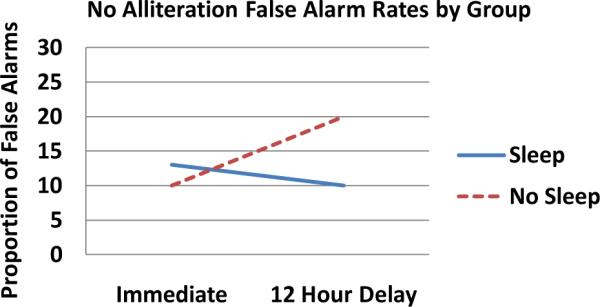

Figure 4.

No Alliteration False Alarm Rates

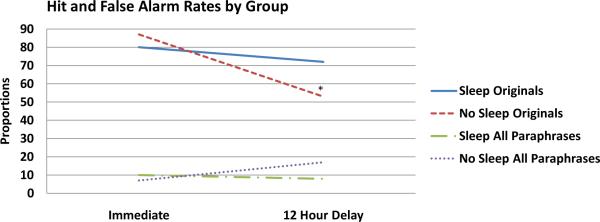

There was a significant interaction between delay type and group for recognition of original lines (F(1, 38) = 6.10, p = 0.018). Performance was high for the sleep group (hit rate = 80 percent) and the no-sleep group (hit rate = 87%) on the immediate recognition task. After the 12 hour delay, the sleep group's recognition of original lines remained stable (hit rate = 72 percent; F(1, 19) = 1.15, p = 0.30), whereas the no-sleep group's performance declined (hit rate = 53 percent; F(1, 19) = 30.0, p < 0.0001; see Figure 5). Schematic errors increased in the no-sleep group over time as well, meaning same alliteration false alarms occurred more often (F(1, 19) = 4.87, p = 0.04; see Figure 6). Reading ability did not correlate with recognition test performance. See Figures 9 and 10 for data summaries.

Figure 5.

Original Phrase Hit Rates by Group

Note. * Indicates significance at a p = .05 level or less.

Figure 6.

Same Alliteration False Alarm Rates by Group

Note. * Indicates significance at a p = .05 level or less.

Figure 9.

Hit and False Alarm Rates Overall

Note. * Indicates significance at a p = .05 level or less.

Figure 10.

Hit and False Alarm Rates by Group

Note. * Indicates significance at a p = .05 level or less.

4. DISCUSSION

Overall we found an increase in same alliteration false alarm rates over time, which suggests form-based schematic learning for the poetry lines. Additionally, the sleep group demonstrated better recognition of original lines and fewer false alarm errors than the no-sleep group after 12 hours. This evidence of memory for form is strengthened by the fact that the different alliteration and no alliteration paraphrases had no significant effects by delay or group. Our results suggest that memory for form can endure for up to 12 hours if sleep has taken place, which offers counter-evidence to the assumption that memory for form decays rapidly (Bransford & Franks, 1971; Brewer & Hay, 1984). Furthermore, recognition for original lines did not significantly decay over time in the sleep group, which suggests that sleep helped preserve memory for form.

Participants seemingly attended to the sound patterns of the poetry lines and used them to construct form-based schemas that facilitated correct recognition of original lines later on. Participants were not simply attending to meaning; they disregarded paraphrases with sound patterns that didn't match the original form-based schemas they had learned. Participants were able to rule out the different and no alliteration paraphrases both immediately and after the delay, regardless of whether or not they had slept. However, same alliteration paraphrases presented a challenge since they were schematically similar to original lines’ sound patterns. Overall, participants were much more likely to make form-based schematic errors by mistaking these same alliteration paraphrases for originals after 12 hours had passed. This effect was much more pronounced if participants had not slept in the interim.

Similarly to Lea and colleagues’ (2008) findings, our participants remembered material better when sound patterns were consistent. This provides additional evidence that alliteration can serve as a memory cue. Furthermore, the sleep group's steady correct recognition of original lines and lower error rates over time support Tillman & Dowling's (2007) findings on the stability of memory for poetry. However, the no-sleep group did not show stable memory for original lines over time, and immediate memory for poetry lines was not poor from the outset in this experiment. Our results also conform to Rubin's (1995) theory that sound patterns can provide a structure, or schema, to aid recall of poetry lines and alliterative lines in particular. As Maquet (2001) proposed, sleep may help stabilize these form-based schemas in memory over time, as with other types of perceptual material.

Our findings also offer an example of how form-based schemas can be double-edged swords in terms of memory, as Brewer & Treyens’ (1981) illustrated in schematic memory for events. False alarm rates for similar-sounding paraphrases increased over time in this study. The lines were remembered schematically rather than verbatim, which resulted in an increase in schema-based errors. As false recognition of same alliteration paraphrases went up over time, correct recognition of original lines went down. Thus, form-based schemas can aid memory while still having some potential for error.

In summary, our results support our hypotheses. Recognition of original lines was less accurate after 12 hours overall. With the groups separated, this was significant only in the no-sleep group. Form-based schematic errors increased after the 12 hour delay as same alliteration paraphrases were mistaken for originals at higher rates. Again, the no-sleep group made this type of error significantly more often. Our findings offer strong evidence that memory for form is not always lost and that form is remembered in the context of poetry, in which form is essential to the material. Indeed, the sleep group had no significant decreases in correct recognition or increases in false alarm rates over time, while the no-sleep group's correct recognition of original lines significantly decreased while same alliteration false alarms increased after 12 hours. Since the no-sleep group was more prone to make schematic errors, this indicates that they did not learn form-based schemas as accurately as the sleep group and therefore had to generalize the information more widely. These results suggest that sound patterns can act as memory cues, that form-based schematic learning takes place for poetic material, and that form-based schemas can endure over time, especially when sleep takes place soon after learning the material.

One limitation to this study is that it is possible that the no-sleep group dealt with more distractors during the 12 hour delay. However, participants in the sleep group slept for an average of seven hours, which left approximately five hours for other information to intrude. In the interest of a naturalistic learning setting, participants were not deprived of sleep nor kept under supervision in the lab for 12 hours. Even if that had been the case, it would have been impossible to prevent participants from encountering or thinking about information other than the poetry lines. Nonetheless, future studies may benefit from keeping participants under supervision for longer delays.

In memory for form, details may be lost over time while a basic structure endures. Form-based schemas enable sound patterns to be anticipated and provide structure through rhythmic constraints (Rubin, 1995), and this study offers evidence that these structures can persist in memory. Humanity's oral traditions have often emphasized form in the past, and this long-standing practice suggests that form may lend an advantage to memory for spoken words. However, form must be rhythmic, relevant to the material, and heard aloud in order to be remembered. Our findings indicate that there is enduring memory for form in the context of poetry, that poetic sound structures are learned schematically, and that sleep may aid these processes. Memory for form is retained in poetry—there is more to it than meaning.

Figure 7.

Different Alliteration False Alarm Rates by Group

Figure 8.

No Alliteration False Alarm Rates by Group

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant HD053136 to Jeff Elman, Mary Hare, and Ken McRae.

APPENDIX

1

Original Line:

The frost-bitten woods wait and keep watch, like a maze mirrored in the lake's surface.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

The frost-bitten wilds withstand and keep wary, like a mist mimicked in the lake's surface.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

The frost-bitten groves grow and keep guard, like a cobweb copied in the lake's surface.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

The frost-bitten forests sway and keep alert, like a net reflected in the lake's surface.

2

Original Line:

And so Grendel waged his lonely war, inflicting constant cruelties on the people.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

And so Grendel worked his lonely wickedness, inflicting continuous conflict on the people.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

And so Grendel conducted his lonely crusade, inflicting steady suffering on the people

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

And so Grendel fought his lonely battle, inflicting unending torture on the people.

3

Original Line:

In his wisdom, the king wondered if the tide of misfortunes would ever turn.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

In his worthiness, the king worried if the trend of misfortunes would ever tire.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

In his practicality, the king pondered if the course of misfortunes would ever change.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

In his insight, the king questioned if the wave of misfortunes would ever end.

4

Original Line:

Beowulf had survived every extreme, excelling himself in daring and danger, until the day arrived.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

Beowulf had survived each excess, exceeding himself in dilemma and difficulty, until the dawn arrived.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

Beowulf had survived all adventures, advancing himself in hardship and hazard, until the hour arrived.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

Beowulf had survived many trials, outdoing himself in bravery and risk, until the time arrived.

5

Original Line:

Friends and young followers flocked to his ranks, a force that grew to fight an army.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

Family and young fellows flew to his ranks, a formation that grew to face an army.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

Allies and young admirers amassed to his ranks, an assembly that grew to assault an army.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

Companions and young supporters rallied to his ranks, a power that grew to battle an army.

6

Original Line:

All were hunted by the dark death-shadow who swooped and lurked in the long nights.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

All were hunted by the demonic doom-shadow who swooped and lay in the lingering nights.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

All were hunted by the gloomy grim-shadow who swooped and crawled in the creeping nights.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

All were hunted by the evil ruin-shadow who swooped and dragged in the boundless nights.

7

Original Line:

In a fury, Beowulf flung his sword away; so must a man do to gain enduring glory.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

In a frenzy, Beowulf flicked his sword away; so must a man do to get enduring greatness.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

In turmoil, Beowulf tossed his sword away; so must a man do to attain enduring adoration. No Alliteration Paraphrase:

In a rage, Beowulf hurled his sword away; so must a man do to win enduring fame.

8

Original Line:

And now Grendel won't be long for this world; he has done his worst but the wound will end him.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

And now Grendel will not be long for this way; he has done his wickedness but the whack will end him.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

And now Grendel shall not be long for this sphere; he has done his slaughter but the slash will end him.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

And now Grendel cannot be long for this earth; he has done his ravaging but the gash will end him.

9

Original Line:

Beowulf got lavish rewards from the lord for his part in the battle: beaten gold and much else.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

Beowulf got luxurious rewards from the leader for his part in the brawl: bountiful gold and much else.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

Beowulf got numerous rewards from the noble for his part in the fighting: fine gold and much else.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

Beowulf got plentiful rewards from the king for his part in the combat: pure gold and much else.

10

Original Line:

With high hearts they went away along trails and footpaths through the fields.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

With happy hopes they went away along trails and furrows through the farms.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

With thrilled thoughts they went away along trails and grasses through the gardens.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

With cheery moods they went away along trails and streams through the pastures.

11

Original Line:

His piercing eyes dim and darken; the dear warrior's death sweeps him away. Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

His piercing eyes dull and deaden; the daring warrior's doom sweeps him away.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

His piercing eyes fog and fade; the favored warrior's fall sweeps him away.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

His piercing eyes haze and cloud; the esteemed warrior's passing sweeps him away.

12

Original Line:

They let the ground keep the gold under the gravel, gone to the earth.

Same Alliteration Paraphrase:

They let the grasses keep the gems under the grime, given to the earth.

Different Alliteration Paraphrase:

They let the dirt keep the diamonds under the dust, dropped to the earth.

No Alliteration Paraphrase:

They let the soil keep the riches under the mud, lost to the earth.

REFERENCES

- Acheson DJ, Wells JB, MacDonald MC. New and updated tests of print exposure and reading abilities in college students. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:278–289. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JR, Pichert J. Recall of previously unrecallable information following a shift in perspective. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1978;17:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bransford JD, Franks JJ. The abstraction of linguistic ideas. Cognitive Psychology. 1971;2:331–350. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer WF, Hay AE. Reconstructive recall of linguistic style. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1984;23:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer WF, Treyens JC. Role of schemata in memory for places. Cognitive Psychology. 1981;13:207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M. The MRC psycholinguistic database. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1981;33A:497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Dowker A. Rhyme and alliteration in poems elicited from young children. Journal of Child Language. 1989;16:181–202. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900013507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumay N, Gaskell MG. Do words go to sleep? Exploring consolidation of spoken forms through direct and indirect measures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28:69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Dumay N, Gaskell MG. Sleep-associated changes in the mental representation of spoken words. Psychological Science. 2007;18:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney S. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. Farrar, Straus, & Giroux; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Karni A, Tanne D, Rubenstein BS, Askenasy JJM, Sagi D. Dependence on REM sleep of overnight improvement of a perceptual skill. Science. 1994;265:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.8036518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea RB, Rapp DN, Elfenbein A, Mitchel AD, Romine RS. Sweet silent thought: Alliteration and resonance in poetry comprehension. Psychological Science. 2008;19:709–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquet P. The role of sleep in learning and memory. Science. 2001;294:1048–1052. doi: 10.1126/science.1062856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp DN, Samuel AG. A reason to rhyme: Phonological and semantic influences on lexical access. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2002;28:564–571. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.28.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers PW. Effect of alliteration on acquisition and retention of meaningful verbal material. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1970;30:671–675. doi: 10.2466/pms.1970.30.2.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC. Memory in Oral Traditions. Oxford University Press; New York and Oxford: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rummer R, Engelkamp J. Phonological information contributes to short-term recall of auditorily presented sentences. Journal of Memory and Language. 2001;45:451–467. [Google Scholar]

- Tillman B, Dowling WJ. Memory decreases for prose, but not for poetry. Memory and Cognition. 2007;35:628–639. doi: 10.3758/bf03193301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]