Significance

Mutations or inactivation of parkin causes Parkinson’s disease (PD) in humans. Recent studies have focused on parkin’s role in mitochondrial quality control in the pathogenesis of PD, including defects in mitophagy, mitochondrial fission, fusion, and transport. This study shows that parkin also controls mitochondrial biogenesis and that defects in mitochondrial biogenesis drive the loss of dopamine (DA) neurons due to the absence of parkin. The findings support the role of parkin in regulating multiple arms of mitochondrial quality control and suggest that maintaining mitochondrial biogenesis is critically important in the survival of DA neurons.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, ZNF746, mitochondrial biogenesis, PARIS, parkin

Abstract

Mutations in parkin lead to early-onset autosomal recessive Parkinson’s disease (PD) and inactivation of parkin is thought to contribute to sporadic PD. Adult knockout of parkin in the ventral midbrain of mice leads to an age-dependent loss of dopamine neurons that is dependent on the accumulation of parkin interacting substrate (PARIS), zinc finger protein 746 (ZNF746), and its transcriptional repression of PGC-1α. Here we show that adult knockout of parkin in mouse ventral midbrain leads to decreases in mitochondrial size, number, and protein markers consistent with a defect in mitochondrial biogenesis. This decrease in mitochondrial mass is prevented by short hairpin RNA knockdown of PARIS. PARIS overexpression in mouse ventral midbrain leads to decreases in mitochondrial number and protein markers and PGC-1α–dependent deficits in mitochondrial respiration. Taken together, these results suggest that parkin loss impairs mitochondrial biogenesis, leading to declining function of the mitochondrial pool and cell death.

Parkin, an ubiquitin E3 ligase, is linked to autosomal recessive Parkinson’s disease (PD) through loss-of-function mutations (1, 2) and to sporadic PD through posttranslational inactivation (reviewed in refs. 3–5). A number of theories have been postulated to account for PD due to parkin inactivation, but it is clear that the loss of parkin’s ubiquitin E3 ligase activity plays a central role in the loss of dopamine (DA) neurons in parkin-linked PD. Parkin conjugates ubiquitin to a variety of proteins using various ubiquitin lysine linkages, including polyubiquitination via lysine-27, -29, -63, and lysine-48 linkages as well as monoubiquitination via lysine-48. Each subtype of parkin ubiquitination has been linked to different physiologic processes (5–7). Polyubiquitination via lysine-48 leads to proteasomal degradation of parkin substrates, and in the absence of parkin these substrates accumulate and contribute to the loss of DA neurons in PD due to parkin inactivation (8–17) (for review see ref. 18).

Recently, the parkin interacting substrate (PARIS) also known as zinc finger protein 746 (ZNF746) was shown to be required for loss of DA neurons in adult conditional parkin knockout (KO) mice (19). PARIS is polyubiquitinated by parkin via lysine-48 targeting it for ubiquitin proteasomal degradation. Deletion of parkin in adult mice leads to an age-dependent progressive loss of DA neurons that is due to the accumulation of PARIS because depletion of PARIS in adult conditional parkin knockout mice prevents the loss of DA neurons (19). PARIS is a transcriptional repressor that regulates the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), a master coregulator of mitochondrial function, biogenesis, and mitochondrial oxidative stress management (19, 20). In adult conditional parkin knockout mice, there is a reduction in PGC-1α levels that is dependent on PARIS because reduction in PARIS reverses the reduction in PGC-1α levels (19). PARIS overexpression, at levels equivalent to those in the adult conditional parkin knockout mice, also leads to defects in PGC-1α and causes the selective loss of DA neurons (19). PGC-1α overexpression prevents the defects in PGC-1α signaling and the loss of DA neurons, suggesting that PARIS kills DA neurons in a PGC-1α–dependent fashion (19).

Because PGC-1α is a master coregulator of mitochondrial function and mitochondrial defects are a consistent feature of PD, mitochondria were assessed in the adult conditional parkin knockout mice. Here we show that adult conditional knockout of parkin leads to reductions in mitochondrial mass that are dependent upon PARIS. Moreover, PARIS accumulation leads to substantial deficits in mitochondrial respiration that are PGC-1α dependent. Our findings are consistent with parkin regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis.

Results

Reduced Mitochondrial Size and Number in Adult Conditional Parkin Knockouts.

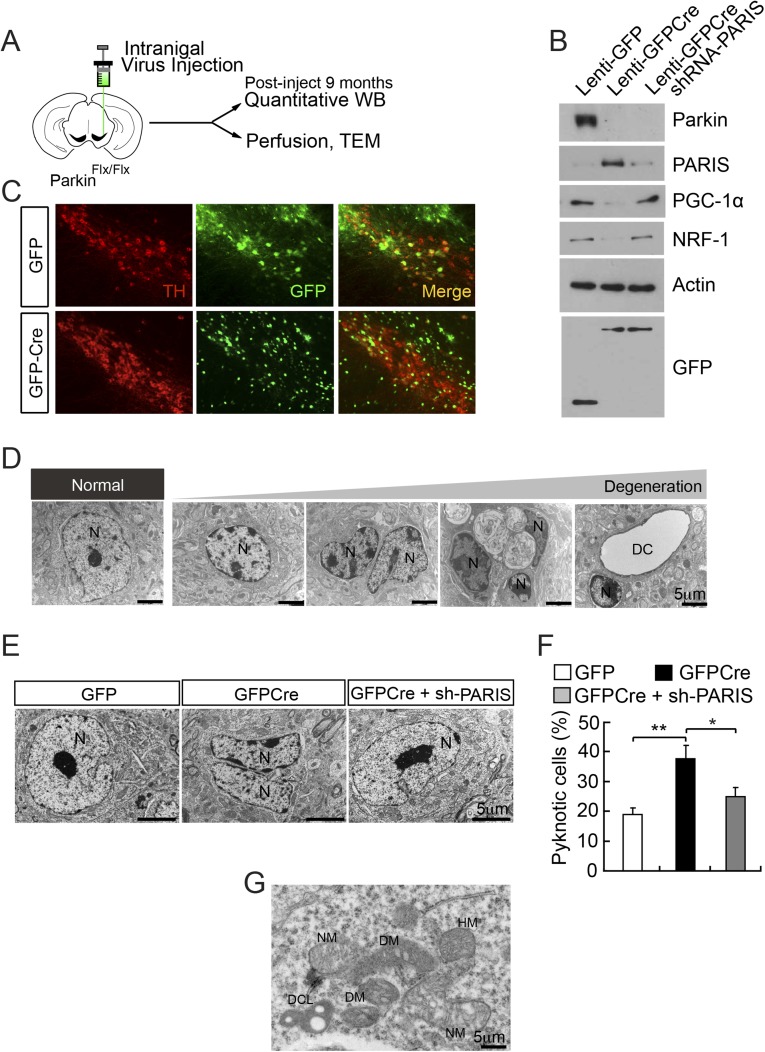

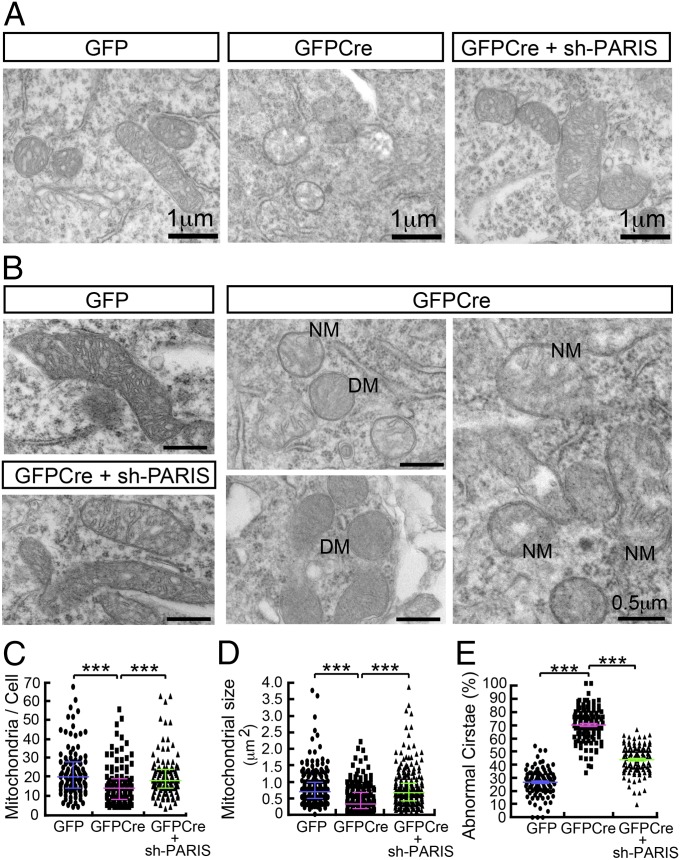

Adult conditional parkin knockout mice were generated as previously described by injecting a lentivirus expressing GFPCre stereotactically into the ventral midbrain of 2-mo-old parkinflx/flx mice (Fig. S1A) (19). In a subset of mice a lentivirus expressing PARIS short hairpin RNA (shRNA) was coinjected to prevent the up-regulation of PARIS due to the deletion of parkin as previously described (19). Lenti-GFPCre leads to almost complete loss of parkin from the ventral midbrain of parkinflx/flx mice compared with lenti-GFP mice (Fig. S1B). Accompanying the loss of parkin is a robust up-regulation of PARIS, resulting in reduction of PGC-1α and nuclear respiratory factor (NRF-1) as previously described (19) (Fig. S1B). Immunostaining for GFP in the intranigral GFP- or GFPCre-injected mice demonstrates that lenti-GFP and lenti-GFPCre effectively transduce neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) including DA neurons (Fig. S1C). Nine months later when active loss of DA neurons is occurring, transmission electron microscopic (TEM) images from the SN were collected to determine the effects of the loss of parkin on nuclear and mitochondrial morphology. Adult knockout of parkin in the SN of mice leads to the clumping of nuclear chromatin and pyknotic nuclei (Fig. S1D). Different levels of clumping of the nuclear chromatin are observed with mild to compact nuclear clumping suggestive of different stages of degeneration (Fig. S1D). In addition, dead cells are observed (Fig. S1 D and E). Quantification of the pyknotic nuclei reveals a significant increase in the percentage of pyknotic nuclei in the adult conditional parkin knockout mice compared with lenti-GFP–injected control mice (Fig. S1 E and F). Knockdown of PARIS via lenti-PARIS shRNA substantially and significantly reduces the percentage of pyknotic nuclei (Fig. S1 E and F). Previous observations assessing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) number in the SN via stereology (19) are consistent with number of pyknotic nuclei due to adult conditional parkin knockout and rescue by coadministration of lenti-PARIS shRNA (Fig. S1 D and E). In ventral midbrain neurons with normal appearing nuclei, TEM image analysis of mitochondrial number and size was performed (Fig. 1 A and B). Mitochondria in the adult conditional parkin knockout mice are smaller in size and number and they have abnormal appearing cristae compared with lenti-GFP–injected control mice (Fig. 1 A and B). Mitochondria in the adult conditional parkin knockout mice with knockdown of PARIS via lenti-PARIS shRNA have normal appearing mitochondria (Fig. 1 A and B). Quantification reveals a 32% reduction in mitochondrial number in adult conditional parkin knockout mice compared with lenti-GFP–injected SN, and knockdown of PARIS via lenti-PARIS shRNA prevents the reduction in mitochondrial number (Fig. 1C). Mitochondria in adult conditional parkin knockout mice are 40% smaller than lenti-GFP–injected SN, and knockdown of PARIS via lenti-PARIS shRNA prevents the reduction in mitochondrial size (Fig. 1D). In adult conditional parkin knockout mice, 69% of the mitochondria have abnormal cristae compared with lenti-GFP–injected SN, and knockdown of PARIS via lenti-PARIS shRNA substantially and significantly prevents the formation of abnormal cristae (Fig. 1E).

Fig. S1.

Adult conditional knockout of parkin. (A) Experimental illustration of generation of conditional KO of parkin via stereotactic intranigral virus injection. Stereotactic delivery of lenti-GFP, lenti-GFPCre, lenti-GFPCre along with lenti-shRNA–PARIS into the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) of exon 7 floxed parkin mice (parkinflx/flx). (B) Immunoblot analysis showing reduced parkin levels and increased PARIS levels. Accompanying the elevation of PARIS is a reduction in the levels of PGC-1α and NRF-1. (C) The efficiency of viral injection was assessed by immunofluoresence in SNpc and coverage was calculated by counting total TH+ and TH+ GFP+ neurons yielding 84.9 ± 1.9% and 78.1 ± 2.6% colocalization in GFP and GFPCre-injected side, respectively (n = 3 per group). (D) Progression of neuronal degeneration in SNpc neurons of conditional knockout of parkin mice compared with healthy normal neuron (Left). (Scale bar, 5 μm.) N, nucleus; DC, dead cell. (E) Postinjection 9 mo, transmission electron micrographs reveal an increase of pyknotic cells in conditional parkin KO mice. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) N, nucleus and representative image showing the reduction of pyknotic cells by PARIS knockdown in conditional parkin KO mice. (F) Quantification of pyknotic cells shown in E, n = 3 mice per group (GFP; n = 90 cells, GFPCre; n = 70 cells, GFPCre + sh-PARIS; n = 85 cells). (G) Representative image of dense core lysosomes (DCL) observed near degenerating (DM) and necrotic mitochondria (NM) in parkin conditional knockout brain sections. HM, healthy mitochondria. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The results were evaluated for statistical significance by applying the one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (F = 11.12, R2 = 0.7875) (F). Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Asterisk indicates statistical significance compared with lenti-GFP vs. lenti-GFPCre and lenti-GFPCre vs. lenti-GFPCre along with lenti-shRNA–PARIS, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Reduced mitochondrial size and number in adult conditional knockout of parkin. (A) High power view of mitochondria in substantia nigra pars compacta. (Scale bar, 1 μm.) (B) Super power view of mitochondria in neurons of substantia nigra pars compacta. (Scale bar, 0.5 μm.) DM, degenerative mitochondria; NM, necrotic mitochondria. (C) Assessment of mitochondrial number per cell, n = 4 mice per group (GFP; n = 108 cells, GFPCre; n = 120 cells, GFPCre + sh-PARIS; n = 111 cells). (D) Measurement of mitochondria size, n = 4 mice per group (GFP; n = 211 mitochondria from 10 cells, GFPCre; n = 204 mitochondria from 12 cells, GFPCre + sh-PARIS; n = 240 mitochondria from 12 cells). (E) Observation of abnormal cristae by TEM images (GFP; n = 108 cells, GFPCre; n = 120 cells, GFPCre + sh-PARIS; n = 111 cells). The results were evaluated for statistical significance by applying the Kruskal–Wallis test (C and D) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (F = 439.7, R2 = 0.7235) (E). Data are expressed as median with interquartile range (75th and 25th quartiles) (C and D) or mean ± SEM (E). Differences were considered significant when ***P < 0.001. Asterisk indicates statistical significance compared with lenti-GFP vs. lenti-GFPCre and lenti-GFPCre vs. lenti-GFPCre along with lenti-shRNA-PARIS, respectively.

Reduced Mitochondrial Content in DA Neurons of Adult Conditional Parkin Knockouts.

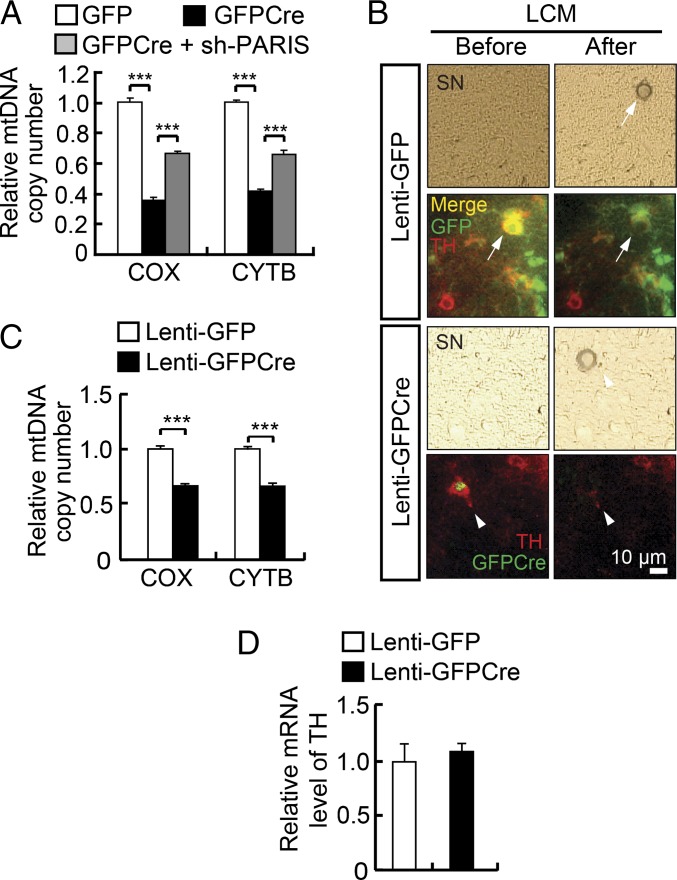

The TEM analysis suggests that there is reduced mitochondrial numbers in adult conditional parkin knockout mice. To confirm whether mitochondrial number is reduced in adult conditional parkin knockout mice, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number was assessed in the adult conditional parkin KO ventral midbrain by measuring two different mitochondrial markers, cytochrome C oxidase (COX) and cytochrome b (CYTB) using real-time quantitative PCR (Fig. 2A). Conditional knockout of parkin in adult mice results in an ∼60% reduction in mitochondrial DNA copy number as assessed by COX and CYTB levels (Fig. 2A). Administration of lentiviral shRNA-PARIS along with lenti-GFPCre significantly reverses the change in COX and CYTB levels (Fig. 2A). To ascertain whether the reduction of COX and CYTB levels is cell autonomous in DA neurons, laser capture microdissection (LCM) was performed in conditional parkin KO mice 4 wk after the lenti-GFPCre injection to obtain DNA and RNA from TH-positive neurons transduced with GFPCre (Fig. 2 B and C). We find a significant reduction of COX and CYTB levels in TH-positive DA neurons of conditional parkin KO mice, whereas the levels of TH mRNA are unchanged (Fig. 2D). Because these changes occur before observation of significant degeneration, reductions in mitochondrial markers in DA neurons likely precedes neuronal degeneration.

Fig. 2.

Reduced mitochondrial content in DA neurons in adult conditional knockout of parkin. (A) The relative quantity of mtDNA using two different mtDNA markers (COX and CYTB) normalized to GAPDH was measured in the ventral midbrain of conditional parkin KO mice 10 mo after lenti-GFPCre deletion of parkin. (B) Representative photomicrographs of laser capture microdissection (LCM) of dopaminergic neurons from conditional parkin KO mice 4 wk after lenti-GFPCre deletion of parkin. Right panels are after LCM and Lower four panels are images from lenti-GFPCre injection compared with lenti-GFP injection as a control (Upper four panels). (C) Using LCM-captured DA neurons, the relative quantity of mtDNA was measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Values were normalized to GAPDH, n = 3 per group. (D) Measurement of TH mRNA indicates that the equal amount of LCM-captured DA neurons were used. The results were evaluated for statistical significance by applying the one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (COX; F = 227.4, R2 = 0.9806, CYTB; F = 234.3, R2 = 0.9812) (A) or unpaired t test (C and D). ***P < 0.001. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

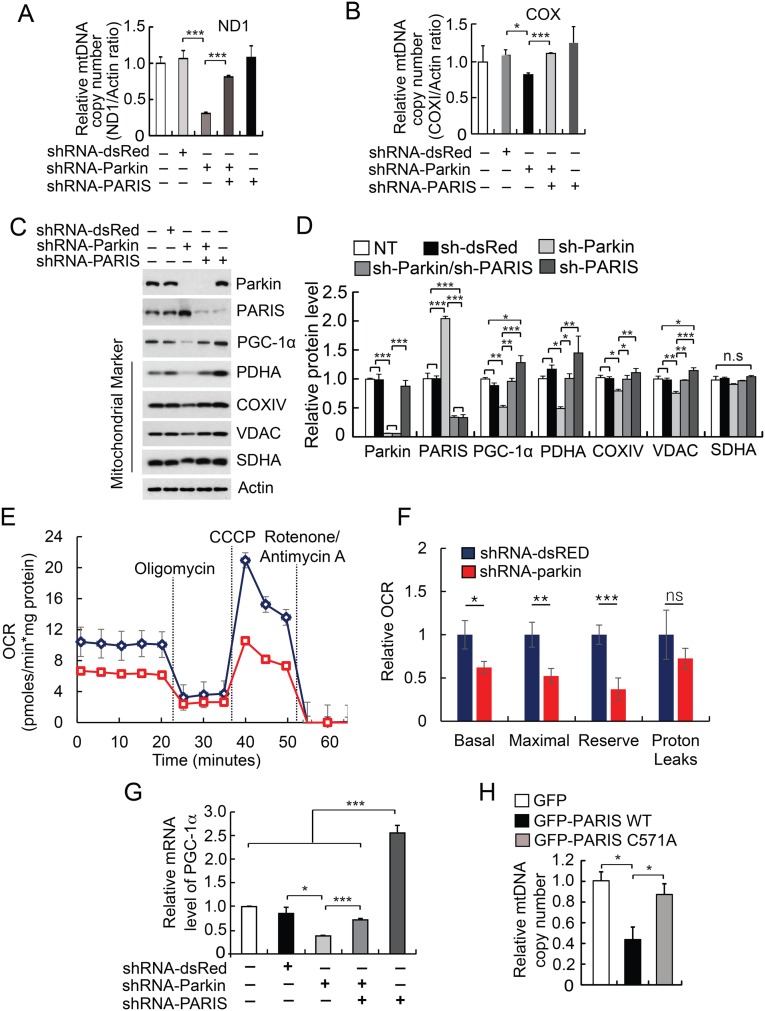

To confirm that the absence of parkin causes a reduction in mitochondrial number, shRNA knockdown of parkin was performed in the SH-SY5Y cell line (Fig. S2). Parkin knockdown via shRNA leads to a significant reduction of mitochondrial copy number as assessed by determining the ratio of the mitochondrial-encoded NADH dehydrogenase 1 (ND1) gene to genomic β-actin as measured by real-time quantitative PCR (Fig. S2A). The reduction in mitochondrial copy number is restored by shRNA-PARIS coadministration (Fig. S2A). There is also a significant reduction of COXI levels induced by parkin knockdown that is PARIS dependent (Fig. S2B). Further analysis indicates that shRNA knockdown of parkin in the SH-SY5Y catecholaminergic cell line causes a twofold increase in the level of PARIS followed by a reduction of PGC-1α and the mitochondrial proteins pyruvate dehydrogenase alpha (PDHA), COXIV, and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), whereas succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit A (SDHA) did not decrease (Fig. S2 C and D). To assess the functional consequences of the observed deficits, we conducted microplate-based respirometry in SHSY-5Y cells transduced with either shRNA-dsRED or shRNA-parkin. Parkin knockdown led to a 38% reduction in basal respiration, a 48% reduction in maximal respiration, and a 63% loss of functional reserve capacity (Fig. S2 E and F). To determine whether the reduction in PGC-1α and the mitochondrial proteins induced by the absence of parkin is dependent on the presence of PARIS, a double knockdown experiment was performed by lentiviral transduction of shRNA against parkin and PARIS in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. S2 C and D). Knockdown of PARIS prevents the down-regulation of PGC-1α and the mitochondrial proteins induced by parkin knockdown (Fig. S2 C and D). As previously described, knockdown of parkin leads to a reduction in the mRNA for PGC-1α and this reduction is eliminated by PARIS knockdown and PARIS knockdown dramatically increases PGC-1α mRNA (19) (Fig. S2G).

Fig. S2.

Parkin knockdown leads to a reduction in mitochondria markers that is PARIS dependent. (A) Relative mtDNA copy number as assessed by real-time quantitative PCR of ND1 in SH-SY5Y cells subjected to parkin and/or PARIS knockdown. Lentivirus-mediated knockdown of parkin leads to 70% reduction of mtDNA and this phenotype was restored by knockdown PARIS (fourth bar) (n = 4, F = 11.39, R2 = 0.7523). (B) Using COXI, the relative mtDNA copy number normalized to genomic GAPDH copy number was determined. (n = 4, F = 9.291, R2 = 0.7124). (C) Immunoblot analysis of parkin, PARIS, PGC-1α, mitochondrial markers (PDHA, COXIV, VDAC, and SDHA), and β-actin in double-knockdown experiments via lentiviral transduction of shRNA-parkin and/or shRNA-PARIS in SH-SY5Y cells, n = 3. (D) Quantitation of the immunoblots in C normalized to β-actin (n = 3, parkin; F = 60.09, R2 = 0.9601, PARIS; F = 144.7, R2 = 0.9830, PGC-1α; F = 18.54, R2 = 0.8812, PDHA; F = 6.198, R2 = 0.7126, COXIV; F = 5.139, R2 = 0.6727, VDAC; F = 14.16, R2 = 0.8500). (E) Composite microplate-based respirometry readings for SH-SY5Y cells transduced with shRNA to parkin (n = 28 replicate wells across four plates) or dsRED (n = 22 replicate wells across four plates). (F) Relative quantification of respirometry data in E. Parkin knockdown leads to a 37.9% reduction in basal oxygen consumption, a 47.8% reduction in maximal respiration, and a 63% reduction in reserve capacity. (G) Relative mRNA levels of PGC-1α normalized to GAPDH, n = 3 (F = 42.78, R2 = 0.9448). (H) Relative quantities of mtDNA as assessed by real-time quantitative PCR of ND1 in SH-SY5Y cells transiently transfected with WT GFP-PARIS and mutant GFP-PARIS C571A (n = 3, F = 9.131, R2 = 0.7527). Quantitative data = mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (A, B, and D–F) or Student’s t test (G and H).

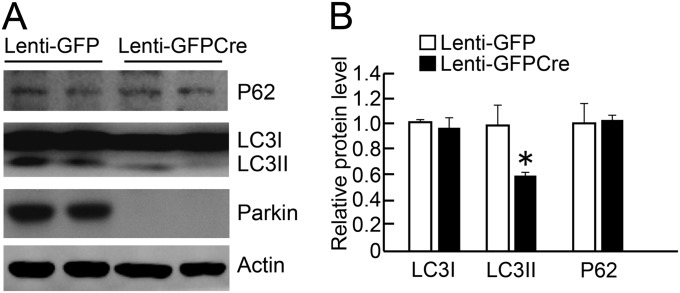

Parkin has been touted to play a role in mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy). If there were defects in mitophagy, one would expect the absence of parkin to increase mitochondrial number through impaired clearance of mitochondrial. However, the deletion of parkin instead leads to reduced mitochondrial number (Fig. 1). To confirm that adult conditional parkin knockout mice do not have a defect in autophagy, the levels of the cytosolic sequestosome 1 (p62) (21) were assessed along with the levels of the microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3 (LC-3) processing from LC-3I to LC-3II (22) (Fig. S3). There is a reduction in LC-3II levels, and there was no substantial change in the levels of p62 after knockout of parkin (Fig. S3). In addition, dense core lysosomes are observed around degenerating or necrotic mitochondria (Fig. S1G) . These results taken together suggest that the adult conditional parkin knockout mice do not have substantial defects in mitophagy.

Fig. S3.

Absence of mitophagy defects in adult conditional knockout of parkin. (A) Intranigral stereotactic injection of lenti-GFPCre lead to almost completely knocked down parkin, a reduction in the level of LC-3II, and no substantial change of the level of LC-3I and P62 compared with lenti-GFP–injected mice as assessed via immunoblot analysis (n = 4 per group). Relative protein levels are normalized to β-actin. (B) Quantitation of immunoblots in A. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05, Student’s t test.

Overexpression of PARIS Leads to Reduced Mitochondrial Markers.

Because PARIS is up-regulated in PD and the conditional parkin KO mice (19), a PARIS overexpression model was used as previously described (19) in which adeno-associated virus serotype 1 (AAV1)-PARIS was stereotactically injected into the SN of C57BL/6 mice and compared with mice injected with control AAV1-GFP virus (Fig. 3A). Stereotactic intranigral injection of AAV1 effectively transduces the entire SN (19). One month after stereotactic injection of the viruses, PARIS, PDHA, COXIV, VDAC, SDHA, and superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) protein levels were determined. AAV1-mediated overexpression of PARIS leads to a greater than twofold up-regulation of PARIS levels in the SN of mice similar to the level of up-regulation of PARIS in sporadic PD and the conditional parkin KO mice (Fig. 3 B and C) (19). Accompanying the increase in PARIS levels is a down-regulation of PDHA, COXIV, VDAC, and SDHA and a trend toward a reduction in SOD1 (Fig. 3 B and C). To assess whether PARIS overexpression has an effect on mitochondrial number, the level of COXIV was assessed and normalized to β-actin via Western blot (Fig. 3 D and E). PARIS overexpression significantly reduces COXIV levels, which are rescued by either AAV1-parkin or lenti–PGC-1α (Fig. 3 D and E). To assess whether PARIS overexpression has an effect on mtDNA copy number, the ratio of mitochondrial ND1 gene to genomic β-actin (23) was measured by real-time quantitative PCR in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with GFP-tagged wild-type (WT) PARIS or GFP-tagged C571A mutant PARIS, which lacks transcriptional repressive activity (19) (Fig. S2H). WT PARIS overexpression leads to a significant 56% reduction of mtDNA copy number, whereas overexpression of C571A mutant PARIS does not affect mtDNA copy number (Fig. S2H).

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of PARIS leads to reduced mitochondrial proteins. (A) Experimental illustration of stereotactic intranigral virus injection. (B) Intranigral stereotactic injection of AAV1-PARIS leads to an up-regulation of PARIS and a reduction in the levels of PDHA, COXIV, VDAC, and SDHA compared with AAV1-GFP–injected mice as assessed via immunoblot analysis 4 wk postinjection (n = 3 per group). Relative protein levels are normalized to β-actin. (C) Quantitation of immunoblots in B. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (D) Immunoblot analysis of PARIS, parkin, PGC-1α, and COXIV, n = 3. (E) Quantitation of COXIV in D normalized to β-actin. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The results were evaluated for statistical significance by applying the unpaired t test (C) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (F = 6.803, R2 = 0.7184) (E). Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

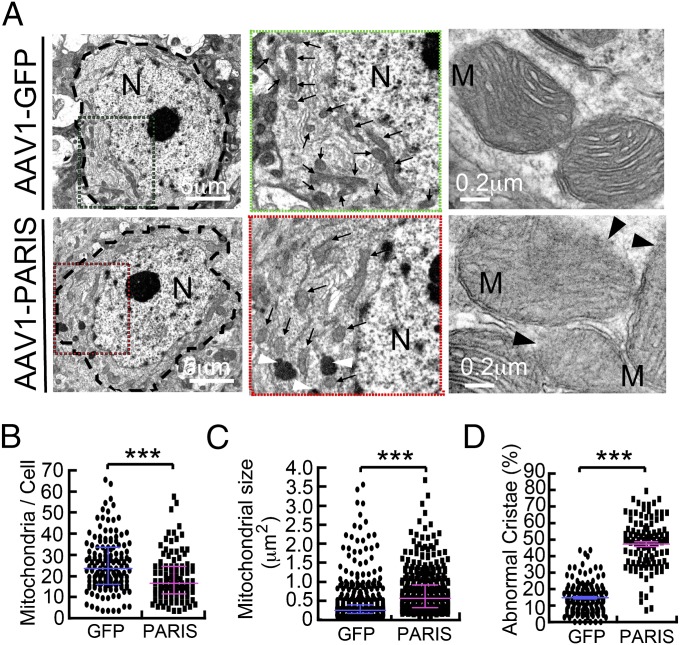

PARIS Overexpression Leads to Reduced Mitochondrial Number and Structural Abnormalities.

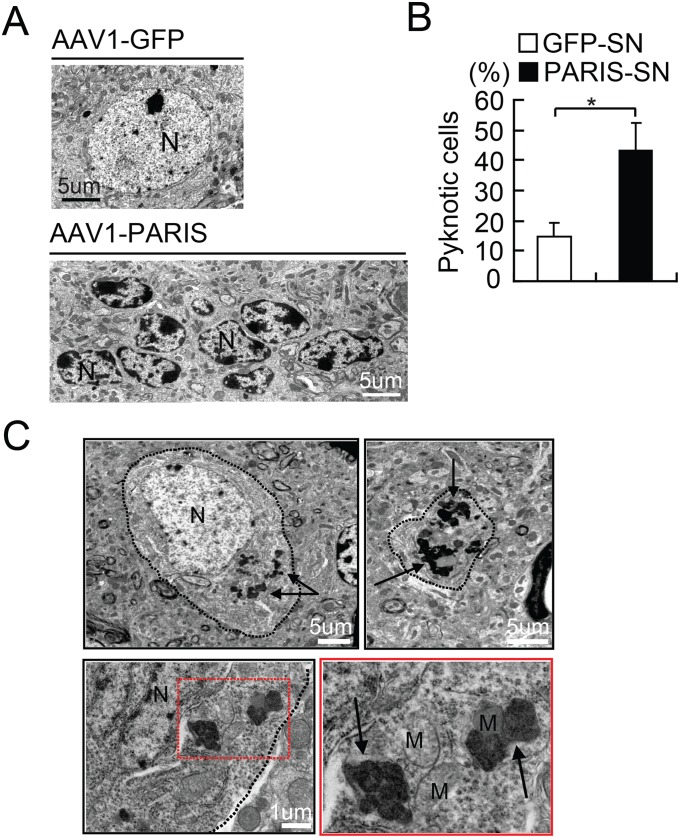

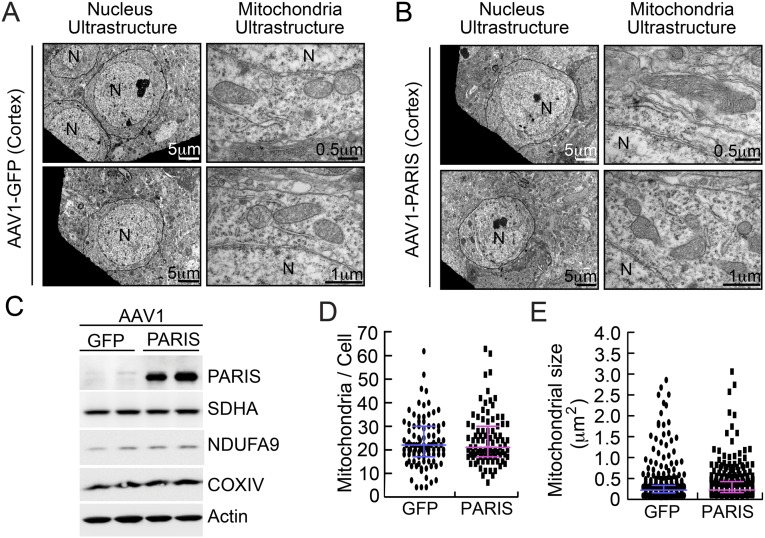

TEM images from SN were collected 4 wk after stereotactic injection of AAV1-GFP or AAV1-PARIS into the SN of WT mice to determine the effects of PARIS overexpression on nuclear and mitochondrial morphology (Fig. 4). PARIS overexpression in the SN of mice leads to the clumping of nuclear chromatin and pyknotic nuclei (Fig. S4 A and B). In AAV1-PARIS–injected SN, 43% of the cells examined have shrunken pyknotic nuclei compared with 15% of the control AAV1-GFP–injected SN similar to adult conditional parkin knockout mice (Fig. S4 A and B). In neurons with normal appearing nuclei, TEM image analysis reveals a 23% reduction in mitochondrial number in AAV1-PARIS–injected SN compared with AAV1-GFP–injected SN (Fig. 5 A and B). Interestingly, the mitochondria in AAV1-PARIS–injected SN are two times bigger than those in AAV1-GFP–injected SN (0.71 μm2 vs. 0.39 μm2, respectively) (Fig. 4 A and C). In AAV1-PARIS–injected SN, 47.5% of the mitochondria have loss of organized cristae compared with 14.8% in control-injected SN (Fig. 4 A and C). Dense core lysosomes are also frequently noted to be clustered around mitochondria (Fig. S4C). No substantial difference in mitochondrial number, size, and ultrastructure is observed in AAV1-GFP– or AAV1-PARIS–injected mouse cortex (Fig. S5 A and B). In addition, there is no reduction in the mitochondrial proteins COXIV, NDUFA9, or SDHA (Fig. S5C). Thus, PARIS overexpression does not cause the same dysfunction of mitochondria in other regions of brain.

Fig. 4.

In vivo overexpression of PARIS leads to mitochondrial dysfunction. (A) TEM of neurons with normal appearing nuclei reveals a decrease in mitochondrial number with notably larger mitochondria (arrows) in AAV1-PARIS–injected SN versus AAV1-GFP–injected SN (Left) as shown in the magnified region flanked by the green/red dotted rectangles (Middle). Further representative image reveals mitochondria lacking organized cristae (Right). (B) TEM image analysis reveals a 23% reduction of mitochondrial number in AAV1-PARIS–injected SN compared with AAV1-GFP–injected SN. The number of mitochondria harboring clear two-layer membranes and size larger than 0.15 μm2 was counted (GFP; n = 145 cells, PARIS; n = 110 cells), n = 4 mice per group. (C) Mitochondria in AAV1-PARIS–injected SN are approximately two times larger than those in AAV1-GFP–injected SN (0.71 μm2 vs. 0.39 μm2 on average). The size of mitochondria in the cells randomly selected from cells with normal appearing nuclei (GFP; n = 519 mitochondria from 19 cells, PARIS; n = 405 from 23 cells) was measured by TEM software, n = 4 mice per group. (D) AAV1-GFP–injected SN leads to a loss of cristae in 14.8% of the mitochondria (n = 145 cells), whereas AAV1-PARIS–injected SN leads to a loss of cristae in 47.5% of the mitochondria (n = 110 cells). (Scale bars as indicated.) The results were evaluated for statistical significance by applying the Mann–Whitney test (B and C) or unpaired t test with Welch’s correction (F = 2.560, R2 = 0.6463) (D). Data are expressed as median with interquartile range (75th and 25th quartiles) (B and C) or mean ± SEM. Differences were considered significant when ***P < 0.001. Asterisk indicates statistical significance compared with AAV1-GFP vs. AAV1-PARIS.

Fig. S4.

In vivo overexpression of PARIS leads to cell death. (A) TEM images 4 wk postinjection showing substantial clumping of chromatin and pyknotic nuclei in many neurons in AAV1-PARIS–injected SN versus AAV1-GFP–injected SN. (B) Image morphological assessment demonstrates that 43% and 15% of cells observed in 0.225 mm2 area were apoptotic in AAV1-PARIS–injected SN versus AAV1-GFP–injected SN, respectively (n = 3 per group). (C) TEM showing active lysosomes clustered with mitochondria in AAV1-PARIS–injected SN. Dense core lysosome are indicated by black arrows. Red line (Bottom Left) outlines DCL. High power view of red rectangles is shown Bottom Right. (Scale bars as indicated.) Quantitative data = mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 in an unpaired two-tailed t test.

Fig. 5.

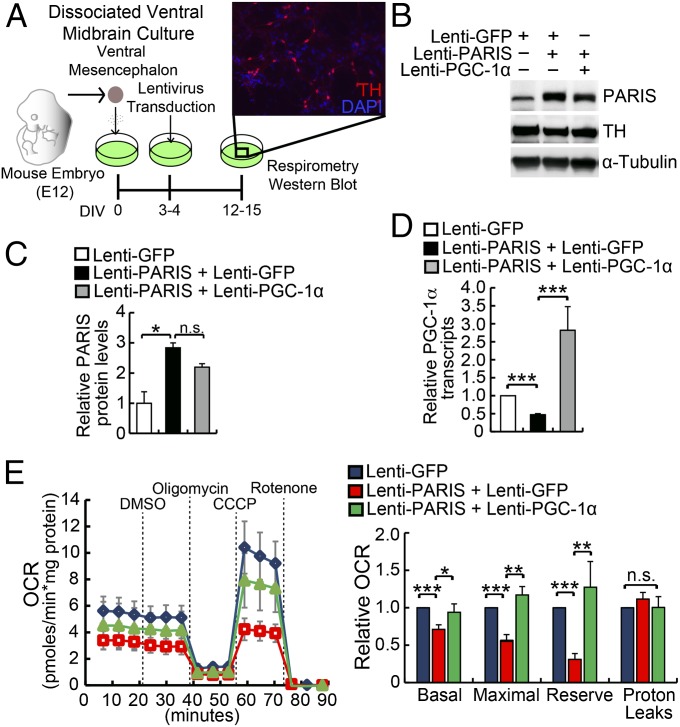

PARIS overexpression leads to mitochondrial respiratory defects. (A) Mouse embryonic ventral midbrain cultures were transduced with the indicated lentivirus from 3–5 d in vitro (DIV). Microplate based respirometry was conducted at 12–15 DIV. Ventral midbrain cultures showed an average of 10.9 ± 2.2% TH positive cells at 15 DIV (n = 3 wells per dissection, 4 dissections). (B and C) PARIS-transduced cultures exhibited a two- to threefold increases in PARIS protein levels compared with lenti-GFP control (n = 3). (D) Lentiviral PARIS-transduced cultures exhibited a 54.1% reduction in PGC-1α transcript levels (n = 6). Transcript levels were restored by transduction with lentiviral PGC-1α (n = 3). (E) Mitochondrial stress testing of the cultures. PARIS overexpression caused a 29.0 ± 6.3% decrease in basal respiration and a 44.5 ± 9.7% decrease in maximal respiration. PARIS overexpression reduced mitochondrial reserve capacity by 69.0 ± 7.8 (n = 5 assays). Concurrent overexpression of PGC-1α rescued these phenotypes (n = 4 assays). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The results were evaluated for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (C–E). Differences were considered significant when *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. S5.

Absence of mitochondrial abnormalities in mouse cortex overexpressing PARIS. (A) TEM images after stereotaxic injection of AAV1-GFP or (B) AAV1-PARIS into cortex. No apparent morphological change was found in between groups. N, nucleus (n = 3). (C) Western blots from total cell lysates of mouse cortical neurons transduced with lentiviral GFP or PARIS. Despite robust PARIS overexpression there is no change in the levels of SDHA, NDUFA9, or COXIV relative to β-actin. (D) TEM image analysis shows no alteration of mitochondrial number in AAV1-PARIS–injected cortex compared with AAV1-GFP–injected cortex (GFP; n = 95 cells, PARIS; n = 92 cells). The number of mitochondria harboring clear two-layer membranes and size larger than 0.15 μm2 was counted. (E) Mitochondria in AAV1-PARIS–injected cortex are comparable to those in AAV1-GFP–injected cortex. The size of mitochondria in the cells randomly selected from cells with normal appearing nuclei (GFP; n = 352 mitochondria from 16 cells, PARIS; n = 321 from 14 cells) was measured by TEM software. The results were evaluated for statistical significance by applying the Mann–Whitney test (D and E). Data are expressed as median with interquartile range (75th and 25th quartiles).

PARIS Overexpression Leads to PGC-1α–Dependent Mitochondrial Respiratory Decline.

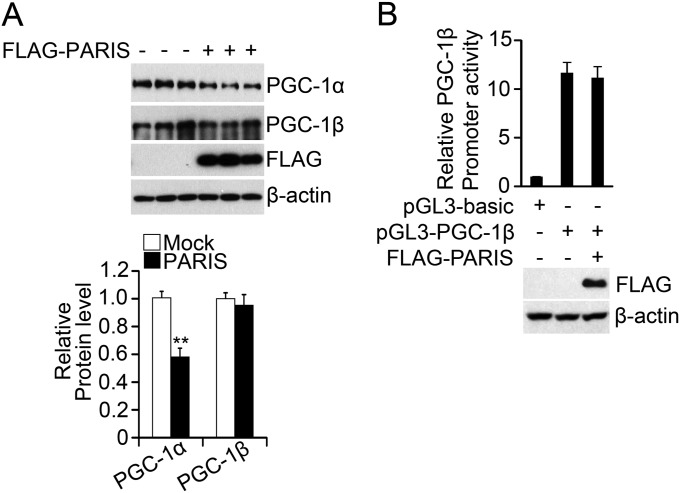

To ascertain the effect of PARIS overexpression on mitochondrial function, mitochondrial respiration was measured in primary ventral midbrain cultures using a XF-24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). TH immunostaining indicates that 10.9 ± 2.2% of the total cells in cultures are DA neurons (Fig. 5A). Lentiviral PARIS transduction leads to a two- to threefold increase in PARIS levels compared with GFP transduced control, similar to the relative increase of PARIS in sporadic PD and in the conditional parkin KO mouse (Fig. 5 B and C) (19). In this system increased PARIS levels lead to a 54% reduction in PGC-1α transcription (Fig. 5D). We assessed mitochondrial respiration and observed a 29% reduction in basal respiration, a 45% reduction in carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP)-induced maximal respiration, and a 69% reduction in spare respiratory capacity (Fig. 5E). These deficits were rescued by restoring PGC-1α levels. Because PGC-1β modulates many of the same target genes as PGC-1α, we assessed whether PARIS regulates PGC-1β. In SH-SY5Y cells transfected with Flag-tagged PARIS, PGC-1β levels are not changed, whereas PGC-1α levels are reduced (Fig. S6A). Moreover, PGC-1β promoter reporter activity is unaltered (Fig. S6B). Taken together, these results indicate that PARIS selectively regulates PGC-1α as previously described (19).

Fig. S6.

PARIS does not regulate PGC-1β. (A) SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with Flag-tagged PARIS. The protein levels of PGC-1α and PGC-1β were monitored by immunoblot analysis (n = 3). (B) The promoter activity of PGC-1β was measured in the presence of Flag-tagged PARIS (n = 3). Quantitative data = mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05 in an unpaired two-tailed t test.

Discussion

The major findings of this manuscript are the observations of reduced mitochondrial size and number along with increased structural abnormalities after adult knockout of parkin in the ventral midbrain of mice. Accompanying the reduction in mitochondrial size and number is a reduction in mitochondrial markers such as PDHA, VDAC, and COXIV. These changes in mitochondrial mass are due to the accumulation of PARIS because knockdown of PARIS eliminates or markedly reduces the changes in mitochondrial mass. Parkin knockdown in SHSY5Y cells recapitulates reductions in mitochondrial DNA copy number and protein markers and leads to concomitant reduction in respiratory function and capacity.

Moreover PARIS overexpression is sufficient to induce deficits in mitochondrial number, increases in abnormal cristae, and reduction of mitochondrial protein markers selectively in the cells of the ventral midbrain. Overexpression of PARIS in primary mouse ventral midbrain cultures leads to reduced oxygen consumption and impaired respiratory reserve capacity consistent with the reduction in mitochondrial mass. In contrast to our findings in the adult conditional parkin knockout, mitochondrial size was increased in AAV1-PARIS–injected mice. One possible reason for this observation may be that the overexpression of PARIS in conjunction with fully functional parkin impairs biogenesis without a direct impact on parkin-mediated regulation of mitochondrial dynamics or mitophagy. Nonetheless, the overall similar reduction in mitochondrial mass, protein markers, and respiratory capacity, coupled with the PARIS-dependent nature of these observations in the parkin knockout models suggests an overall redundancy in the pathogenic mechanism.

Because PARIS is a transcriptional repressor that accumulates and regulates the levels of PGC-1α specifically in DA neurons (19), the reduction in mitochondrial number, indices, and function in the adult conditional parkin knockout mice is likely due to PARIS-mediated repression of PGC-1α. PGC-1α is a major regulator of mitochondrial size, number, and function (24). Methylation of the PGC-1α promoter is known to lead to decreased mitochondrial size and number and decreases in respiratory chain components (25). Thus, chronic repression of the PGC-1α promoter by PARIS accumulation, as seen in parkin inactivation, likely hinders the production of new mitochondrial proteins, leading to reductions in overall cellular mitochondrial content. This reduction of mitochondria may in turn cause the defects in oxidative phosphorylation (19, 26).

Whereas studies in patient tissues and genetic models frequently report impaired mitochondrial function, few studies have looked at mitochondrial number in PD or PD models. In Drosophila studies, parkin loss seems to lead to increased mitochondrial size; however, studies in mammalian neurons suggest that parkin loss leads to an increased prevalence of smaller mitochondria and a reduced fractional volume of mitochondria. Germ-line parkin knockout mice exhibit reductions in a number of mitochondrial proteins without observed changes in mitochondrial morphology or DA neuron loss (27, 28). A recent report shows reduced mitochondrial fractional volume in DA neurons from patients with parkin mutations as well as in DA cells from an isogenic parkin KO-inducible pluripotent stem cell line (28). Whereas PGC-1α is involved in transcriptional regulation of numerous bioenergetic and antioxidant pathways we focused primarily on investigating defects of oxidative phosphorylation because of its importance in energy production in neurons as well as previous evidence of ox/phos defects found in the PD literature. Further study would be need to investigate the differential impact of parkin loss on other metabolic pathways.

Parkin has been touted to regulate mitochondrial quality control including mitophagy, transport, fission, and fusion (for review see ref. 29). Our findings would suggest that parkin also regulates mitochondrial number and size in a PARIS-dependent manner. The reduction in mitochondrial number, size, function, and markers coupled with consistent and chronic PGC-1α repression suggests that the absence of parkin leads to a mitochondrial biogenesis defect.

Defects in mitophagy were not observed in adult conditional parkin knockouts and would not explain the observations reported here. One might expect increased mitochondrial number and proteins if there were defects in mitophagy, but instead mitochondrial number and markers were reduced. Other investigators have failed to observe mitophagy defects in parkin knockouts and in patients with parkin mutations (27). In addition, mitophagy defects were not observed even in the setting of mitochondrial stressors in parkin knockouts (30, 31). We cannot exclude the possibility that there are defects in mitophagy, transport, fission, and fusion due to the absence of parkin and up-regulation of PARIS, but our data would suggest the PARIS up-regulation and PGC-1α suppression and decrements in mitochondrial biogenesis are the primary driver of DA neuron loss. Under physiologic conditions in the presence of parkin, there is likely a homeostatic mechanisms that regulates the level of mitochondrial numbers in response to the needs of the cell in a balanced pathway of degradation (mitophagy) and production (biogenesis) of mitochondria that is regulated by parkin, with PARIS playing a central role in the biogenesis arm. Consistent with the notion of a homeostatic mechanism is the recent report of the coordination of mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis during aging in Caenorhabditis elegans (32). Further studies are required to investigate this possibility.

In light of the experimental findings that PARIS regulates PGC-1α, mitochondrial integrity, and dopaminergic neuronal viability, it is likely that increased PARIS levels in PD due to parkin inactivation contribute to the pathogenesis of this neurodegenerative disease through down-regulation of PGC-1α and some of its target genes. Consistent with this notion, the loss of DA neurons and many of the mitochondrial abnormalities are rescued by knockdown of PARIS and overexpression of parkin or PGC-1α (19). Germ-line deletion of PGC-1α fails to lead to loss of DA neurons in mice (33), which is similar to the lack of DA neuronal loss following germ-line deletion of parkin, which may be due to compensation during development in the dopaminergic system (19, 34, 35). Based on the observations reported here, it is likely that deletion of PGC-1α in adult animals will lead to degeneration of DA neurons. Future studies will be required to test this possibility. In summary, it seems that defects in mitochondrial biogenesis due to PARIS-mediated down-regulation of PGC-1α is one of the major drivers of DA neuron degeneration due to the absence of parkin.

Materials and Methods

Full methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods. Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC) were used. For microplate respirometry, cells were maintained in DMEM with no glucose supplemented with 25 mM galactose. Brain tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer using a Diax 900 homogenizer. An AAV1 expression plasmid (AAV/CBA-WPRE-bGHpA) under the control of a CBA (chicken beta-actin) promoter and containing woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional-regulatory element (WPRE) and bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) was used for expression of PARIS and GFP. Lentivirus was used to express shRNA plasmids encoding small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting parkin or PARIS as previously described (19). For stereotactic injection of AAV1 overexpressing GFP or PARIS and lentivirus overexpressing GFP or GFPCre, experimental procedures were followed according to the guidelines of Laboratory Animal Manual of the National Institute of Health Guide to the Care and Use of Animals, which were approved by The Johns Hopkins Medical Institute Animal Care Committee. To generate the Cre-flox conditional model of parkin knock out, lentiviral vector expressing GFP-fused Cre recombinase (lenti-GFPCre) was stereotactically introduced into exon 7 floxed parkin mice (parkinFlx/Flx) in 6- to 8-wk-old mice. Furthermore lentiviral shRNA-PARIS was coadministrated along with lenti-GFPCre to demonstrate whether the changes in the contents of mtDNA were due to PARIS. Mice were perfused with PBS containing 1% sodium nitrite (pH 7.4), fixed with fixative consisting of 3% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde, 1.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, 100 mM cacodylate, 2.5% (vol/vol) sucrose (pH 7.4), and postfixed for 1 h and brain sections were processed as described (36). Primary mouse ventral midbrain cultures were prepared from E12.5–E14.5 mouse embryos and were assayed at 12–15 days in vitro (DIV) using a standard mitochondrial stress test paradigm on the Seahorse Bioscience XF-24 analyzer. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software).

SI Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Antibodies.

The antibody against PARIS was generated as described (19). Primary antibodies used include the following: mouse anti–PGC-1α (4C1.3, Calbiochem), rabbit anti–PGC-1β (NBP1-28722, Novus Biologicals), rabbit anti-NRF1 (ab34682, Abcam), mouse antiparkin (Park8, Cell Signaling), rabbit antityrosine hydroxylase (TH) (Novus Biologicals), mouse anti-GFP (ab1218, Abcam), mitochondrial marker sampler kit (Cell Signaling); secondary antibodies used include donkey anti-rabbit–Cy3, donkey anti-mouse–Cy2 for immunostaining. Full-length parkin, PARIS WT, and PARIS C571A were constructed as described previously (19). Lentiviral pLV–PGC-1α plasmid was kindly provided by Dimitri Krainc, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA. pGL3–PGC-1β luciferase vector was generated by inserting human PGC-1β promoter (−1231 ∼ +44, NG_016747.1) into pGL3 basic with Kpnl/Bglll restriction sites.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC) were grown in DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS and antibiotics in a humidified 5% CO2/95% (vol/vol) air atmosphere at 37 °C. For microplate respirometry, cells were maintained in DMEM with no glucose supplemented with 25 mM galactose. For transient transfection, cells were transfected with indicated amounts of target vector using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen), or Fugene HD (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Preparation of Tissues for Western Blot.

Brain tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer [10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM Na-β-glycerophosphate, Phosphate Inhibitor Mixture I and II (Sigma), and Complete Protease Inhibitor Mixture (Roche)], using a Diax 900 homogenizer. After homogenization, samples were rotated at 4 °C for 30 min for complete lysis, then the homogenate was centrifuged at 52,000 rpm in a Beckman Coulter (Optima TLX micro-ultracentrifuges, TLA 100.3 rotor) for 20 min, and the resulting fractions were collected. Protein levels were quantified using the BCA kit (Pierce) with BSA standards and analyzed by Western blot. The densitometric analyses of the bands were performed using ImageJ (NIH, rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

AAV1-Plasmid Construction and Generation of AAV1 Virus.

cDNAs for PARIS and parkin were subcloned into an AAV1 expression plasmid (AAV/CBA-WPRE-bGHpA) under the control of a chicken beta-actin (CBA) promoter and containing woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional-regulatory element (WPRE), and bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). Destabilized GFP (dGFP) was cloned into the same AAV expression vector backbone and used as control vector. High-titer AAV virus generation and purification were performed as described in detail elsewhere (37).

Lentiviral shRNA Constructs.

MISSION short hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmids encoding small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting parkin or PARIS were purchased from Sigma. TRCN0000000285 and TRCN0000000283 vectors successfully knocked down human parkin as previously described (19). Three plasmids (TRCN0000156627, TRCN0000157534, and TRCN0000157931) were effective in knocking down PARIS expression as previously described (19). As a control, shRNA-dsRed coexpressing GFP and short hairpin sequence (AGTTCCAGTACGGCTCCAA) under the control of the EF1α and human U6 promoter was used. For knockdown of human parkin or PARIS in SH-SY5Y cells, two lentiviral vectors were combined and TRCN0000157931 lentiviral vector was used to knockdown mouse PARIS in vivo.

Stereotaxic Injection.

For stereotactic injection of AAV1 overexpressing GFP or PARIS and lentivirus overexpressing GFP or GFPCre, experimental procedures were followed according to the guidelines of Laboratory Animal Manual of the National Institute of Health Guide to the Care and Use of Animals, which were approved by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institute Animal Care Committee. Six- to eight-week-old male C57BL mice (Charles River Laboratories) or parkinFlx/Flx were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg). An injection cannula (26.5 gauge) was applied stereotactically into the SN (anteroposterior, −3.0 mm from bregma; mediolateral, 1.2 mm; dorsoventral, 4.3 mm), or cortex (anteroposterior, 1.0 mm from bregma; mediolateral, 2 mm; dorsoventral, 1.5 mm).

Conditional Parkin Knockout.

To generate the Cre-flox conditional model of parkin knockout, lentiviral vector expressing GFP fused Cre recombinase (lenti-GFPCre) was stereotactically introduced into exon 7 floxed parkin mice (parkinFlx/Flx) in 6- to 8-wk-old mice. Furthermore lentiviral shRNA-PARIS was coadministrated along with lenti-GFPCre to demonstrate whether the changes in the contents of mtDNA were due to PARIS.

TEM Imaging and Mitochondrial Assessment.

Mice were perfused with PBS containing 1% sodium nitrite (pH 7.4), fixed with fixative consisting of 3% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde, 1.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, 100 mM cacodylate, 2.5% (vol/vol) sucrose (pH 7.4), and postfixed for 1 h. Brain sections were processed as described (36). Images were collected on a Philips EM 410 TEM installed with a Soft Imaging System Megaview III digital camera. To quantify the number of apoptotic cells and mitochondrial abnormalities, extensive image analysis was performed on ∼0.225 mm2 area per mouse. Chromatin clumping, loss of cytoplasm (shrinkage), lack of membrane layers, and ultrastructural cristae were considered as morphologic markers for apoptosis and loss of ultrastructure. The TEM image tool was used to measure the size of mitochondria on randomly chosen cells and the number of mitochondria harboring clear two-layer membranes and sizes larger than 0.15 μm2 were counted to minimize bias.

Determination of mtDNA Copy Number Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR.

Total DNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and aliquots of DNA were used as templates for real-time quantitative PCR procedure. Relative quantities of mtDNA were analyzed using real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System, Applied Biosystems). The SYBR greenER reagent (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The primer sequences are listed as follows: For human sequences: β-actin forward, 5′-CATGTGCAAGGCCGGCTTCG-3′, β-actin reverse 5′-CTGGGTCATCTTCTCGCGGT-3′; mtDNA ND1 forward 5′-TCTCACCATCGCTCTTCTAC-3′, mtDNA ND1 reverse 5′-TTGGTCTCTGCTAGTGTGGA-3′; COXI forward, 5′-TTCGCCGACCGTTGACTATTCTCT-3′, COXI reverse, 5′-AAGATTATTACAAATGCATGGGC-3′; for mouse sequences: GAPDH forward, 5′-TGGGTGGAGTGTCCTTTATCC-3′, GAPDH reverse 5′-TATGCCCGAGGACAATAAGG-3′; mtDNA COX1 forward 5′-GCCTTTCAGGAATACCACGA-3′, mtDNA COX1 reverse 5′-AGGTTGGTTCCTCGAATGTG-3′; mtDNA CYTB forward 5′-ATTCCTTCATGTCGGACGAG-3′, mtDNA CYTB reverse 5′-ACTGAGAAGGCCCCCTCAAAT-3′.

Mouse Embryonic Ventral Midbrain Culture.

Primary mouse ventral midbrain cultures were prepared from E12.5–E14.5 mouse embryos. Dissection was performed in ice cold HBSS with 20% (vol/vol) horse serum, 200 μM ascorbic acid, and penicillin/streptomycin. Narrowly dissected ventral midbrain sections were incubated in Accutase for 5–7 min and then manually dissociated. Cell suspensions were then diluted in plating media [Neurobasal media (Invitrogen), 2% (vol/vol) horse serum, 2 mM glutamine, 1× B-27 supplement (Invitrogen) conditioned in mature astrocyte cultures filtered and supplemented with freshly prepared 200 μM ascorbic acid]. Cell suspensions were filtered through 70-μm2 cell filters and plated on poly-l-ornithine and laminin-coated seahorse plates at a density of ∼200,000 cells per well. Viral transduction was conducted from 3–5 DIV. Assays were conducted 7–10 d posttransduction.

Microplate-Based Respirometry.

Primary mouse ventral midbrain cultures were assayed at 12–15 DIV using a standard mitochondrial stress test paradigm on the Seahorse Bioscience XF-24 analyzer. SHSY-5Y cells were assayed 96 h posttransduction. Cells were washed once with assay media (DMEM with 10 mM glucose, 1 mM pyruvate and 2 mM glutamine) before adding 675 μL of assay media to each well and incubating in a non-CO2, 37 °C incubator for 30–60 min. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured using a 1 min mix, 1 min wait, 2 min measurement cycle. Injection ports contained: (i) DMSO (0.002% vol/vol), (ii) oligomycin (1.25 μg/mL), (iii) carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP) (1.25 μM) and (iv) rotenone (1 μM). For SH-SY5Y cells antimycin-A (1 μM) was added to the final injection port. OCR values were normalized to total protein, determined for each well by BCA assay, and rotenone insensitive (nonmitochondrial) oxygen consumption was subtracted from all values. Basal respiration was calculated using the mean of the three OCR measurements before the first injection and maximal respiration was calculated as the mean of three OCR measurement cycles after CCCP injection. Reserve capacity was calculated by subtracting the basal OCR values from CCCP-induced maximal OCR. Proton leaks were calculated by subtracting rotenone-insensitive OCR values from basal OCR.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software). Data were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirinov test. Comparative data showing the lack of normality were analyzed using nonparametric Mann–Whitney test (for two-group comparison) or Kruskal–Wallis test (for three-group comparison). For nonparametric analysis, data were expressed as median and interquartile range. Whereas datasets were sampled from normal distribution, F tests (for two-group comparison) or Bartlett’s test (for three-group comparison) were used to assess the equal variances. Comparative data showing significant difference of variance were subject to unpaired t test with Welch’s correction (for two-group comparison) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (for three-group comparison). Data were expressed as mean and SEM. The number of animals used in the TEM study was estimated based on the mean difference from our preliminary experiments. From these data, we could infer that a sample size of four per group would provide an actual power >0.95 (effect size f = 1.66 for 15% mean difference, α = 0.05) by using G*Power 3.1 software (www.gpower.hhu.de). For immunoblot and PCR analysis, sample sizes were similar to those used by others in the field.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS38377 and the JPB Foundation. The authors acknowledge the joint participation by the Adrienne Helis Malvin Medical Research Foundation and the Diana Helis Henry Medical Research Foundation through their direct engagement in the continuous active conduct of medical research in conjunction with The Johns Hopkins Hospital, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and the Foundation’s Parkinson’s Disease Programs M-1, M-2, and H-2014. T.M.D. is the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Professor in Neurodegenerative Diseases. This study was partially supported by National Research Foundation Grant 2012R1A1A1012435, the Korean Ministry of Science, Information, Communications, and Technology (ICT) and Future Planning (MSIP), and Samsung Biomedical Research Institute Grant SMX1132521.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1500624112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Abbas N, et al. French Parkinson’s Disease Genetics Study Group and the European Consortium on Genetic Susceptibility in Parkinson’s Disease A wide variety of mutations in the parkin gene are responsible for autosomal recessive parkinsonism in Europe. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(4):567–574. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitada T, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392(6676):605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corti O, Lesage S, Brice A. What genetics tells us about the causes and mechanisms of Parkinson’s disease. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(4):1161–1218. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson TM. Parkin and defective ubiquitination in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2006;(70):209–213. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore DJ. Parkin: A multifaceted ubiquitin ligase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34(Pt 5):749–753. doi: 10.1042/BST0340749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisler S, et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(2):119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olzmann JA, Chin LS. Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination: A signal for targeting misfolded proteins to the aggresome-autophagy pathway. Autophagy. 2008;4(1):85–87. doi: 10.4161/auto.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung KK, et al. S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates ubiquitination and compromises parkin’s protective function. Science. 2004;304(5675):1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.1093891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cookson MR. Parkin’s substrates and the pathways leading to neuronal damage. Neuromolecular Med. 2003;3(1):1–13. doi: 10.1385/NMM:3:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imam SZ, et al. Neuroprotective efficacy of a new brain-penetrating C-Abl inhibitor in a murine Parkinson’s disease model. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e65129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imam SZ, et al. Novel regulation of parkin function through c-Abl-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31(1):157–163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1833-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MY, Mauro S, Gévry N, Lis JT, Kraus WL. NAD+-dependent modulation of chromatin structure and transcription by nucleosome binding properties of PARP-1. Cell. 2004;119(6):803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ko HS, et al. Phosphorylation by the c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase inhibits parkin’s ubiquitination and protective function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(38):16691–16696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006083107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaVoie MJ, Ostaszewski BL, Weihofen A, Schlossmacher MG, Selkoe DJ. Dopamine covalently modifies and functionally inactivates parkin. Nat Med. 2005;11(11):1214–1221. doi: 10.1038/nm1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng F, et al. Oxidation of the cysteine-rich regions of parkin perturbs its E3 ligase activity and contributes to protein aggregation. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C, et al. Stress-induced alterations in parkin solubility promote parkin aggregation and compromise parkin’s protective function. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(24):3885–3897. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao D, et al. Nitrosative stress linked to sporadic Parkinson’s disease: S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(29):10810–10814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404161101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Parkin plays a role in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2014;13(2-3):69–71. doi: 10.1159/000354307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin JH, et al. PARIS (ZNF746) repression of PGC-1α contributes to neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Cell. 2011;144(5):689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St-Pierre J, et al. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127(2):397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myeku N, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Dynamics of the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins by proteasomes and autophagy: Association with sequestosome 1/p62. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(25):22426–22440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.149252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and autophagy. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;445:77–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-157-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HC, Lu CY, Fahn HJ, Wei YH. Aging- and smoking-associated alteration in the relative content of mitochondrial DNA in human lung. FEBS Lett. 1998;441(2):292–296. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin J, Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab. 2005;1(6):361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrès R, et al. Non-CpG methylation of the PGC-1alpha promoter through DNMT3B controls mitochondrial density. Cell Metab. 2009;10(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schon EA, Przedborski S. Mitochondria: The next (neurode)generation. Neuron. 2011;70(6):1033–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palacino JJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in parkin-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):18614–18622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaltouki A, et al. Mitochondrial alterations by PARKIN in dopaminergic neurons using PARK2 patient-specific and PARK2 knockout isogenic iPSC lines. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(5):847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scarffe LA, Stevens DA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkin and PINK1: Much more than mitophagy. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37(6):315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kageyama Y, et al. Mitochondrial division ensures the survival of postmitotic neurons by suppressing oxidative damage. J Cell Biol. 2012;197(4):535–551. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterky FH, Lee S, Wibom R, Olson L, Larsson NG. Impaired mitochondrial transport and Parkin-independent degeneration of respiratory chain-deficient dopamine neurons in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(31):12937–12942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103295108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palikaras K, Lionaki E, Tavernarakis N. Coordination of mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis during ageing in C. elegans. Nature. 2015;521(7553):525–528. doi: 10.1038/nature14300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin J, et al. Defects in adaptive energy metabolism with CNS-linked hyperactivity in PGC-1alpha null mice. Cell. 2004;119(1):121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawson TM, Ko HS, Dawson VL. Genetic animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2010;66(5):646–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Von Coelln R, et al. Loss of locus coeruleus neurons and reduced startle in parkin null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(29):10744–10749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401297101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCaffery JM, Farquhar MG. Localization of GTPases by indirect immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 1995;257:259–279. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)57031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.During MJ, Young D, Baer K, Lawlor P, Klugmann M. Development and optimization of adeno-associated virus vector transfer into the central nervous system. Methods Mol Med. 2003;76:221–236. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-304-6:221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]