Abstract

Background and Purpose

This American Heart Association (AHA) scientific statement provides a comprehensive overview of current evidence on the burden cardiovascular disease (CVD) among Hispanics in the United States. Hispanics are the largest minority ethnic group in the United States, and their health is vital to the public health of the nation and to achieving the AHA’s 2020 goals. This statement describes the CVD epidemiology and related personal beliefs and the social and health issues of US Hispanics, and it identifies potential prevention and treatment opportunities. The intended audience for this statement includes healthcare professionals, researchers, and policy makers.

Methods

Writing group members were nominated by the AHA’s Manuscript Oversight Committee and represent a broad range of expertise in relation to Hispanic individuals and CVD. The writers used a general framework outlined by the committee chair to produce a comprehensive literature review that summarizes existing evidence, indicate gaps in current knowledge, and formulate recommendations. Only English-language studies were reviewed, with PubMed/MEDLINE as our primary resource, as well as the Cochrane Library Reviews, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the US Census data as secondary resources. Inductive methods and descriptive studies that focused on CVD outcomes incidence, prevalence, treatment response, and risks were included. Because of the wide scope of these topics, members of the writing committee were responsible for drafting individual sections selected by the chair of the writing committee, and the group chair assembled the complete statement. The conclusions of this statement are the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the AHA. All members of the writing group had the opportunity to comment on the initial drafts and approved the final version of this document. The manuscript underwent extensive AHA internal peer review before consideration and approval by the AHA Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee.

Results

This statement documents the status of knowledge regarding CVD among Hispanics and the sociocultural issues that impact all subgroups of Hispanics with regard to cardiovascular health. In this review, whenever possible, we identify the specific Hispanic subgroups examined to avoid generalizations. We identify specific areas for which current evidence was less robust, as well as inconsistencies and evidence gaps that inform the need for further rigorous and interdisciplinary approaches to increase our understanding of the US Hispanic population and its potential impact on the public health and cardiovascular health of the total US population. We provide recommendations specific to the 9 domains outlined by the chair to support the development of these culturally tailored and targeted approaches.

Conclusions

Healthcare professionals and researchers need to consider the impact of culture and ethnicity on health behavior and ultimately health outcomes. There is a need to tailor and develop culturally relevant strategies to engage Hispanics in cardiovascular health promotion and cultivate a larger workforce of healthcare providers, researchers, and allies with the focused goal of improving cardiovascular health and reducing CVD among the US Hispanic population.

Keywords: AHA Scientific Statements, cardiovascular disease, Hispanic, Latino, stroke

More than 53 million Hispanics currently live in the United States, which constitutes 17% of the total US population. They represent the fastest-growing racial or ethnic population in the United States and are expected to constitute 30% of the total US population by 2050. Hispanics are a diverse ethnic population, varying in race, national origin, immigration status, and other socioeconomic characteristics. Despite the growing numbers of US Hispanics, many continue to face health disparities. Moreover, the diversity among US Hispanics presents many challenges. In particular, comprehensive research data on the prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) among Hispanic subgroups have been lacking.1 An incomplete understanding of Hispanic populations in academic research has produced a lack of comprehensive data addressing Hispanic health and CVD, discordant literature regarding CVD risk factors and its prevalence, and a decreased understanding of health status and risk factors contributing to health disparities for US Hispanics.

Cardiovascular research has relied heavily on national surveys of US Hispanics such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Yet many of these surveys have examined Hispanics as an aggregated group without identifying their background of origin. It was only in 2007 that NHANES revised its sampling methodology to oversample all Hispanics and not just Mexican Americans. The greater availability of data on Mexican Americans than on other Hispanic groups may simply reflect their larger numerical presence within the United States, but it may not be appropriate to extrapolate these data to the other Hispanic groups. Additional limitations, particularly regarding Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HHANES) data collected 3 decades ago, may not accurately reflect the current burden of CVD risk factors among present-day US Hispanics. Despite these limitations, the aforementioned studies have described a sizeable burden of CVD risk factors among US Hispanics, which suggests a need for further examination and study.2,3 Recent findings from the Hispanic Communities Health Study–Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) emphasize the importance of examining the heterogeneity within the Hispanic population and confirm markedly different adverse CVD risk profiles for Hispanic subgroups.1

Because of a lack of comprehensive data and limited interventions addressing Hispanic health, disparities, and CVD, this writing group has conducted a comprehensive review to summarize findings from a variety of sources, including historical, interventional, and observational studies that focused on Hispanic populations. We also conducted our literature search to report, when available, on specific Hispanic subgroups examined, to avoid generalizations. In studies in which the Hispanic background group was not specified, we simply refer to the participants as Hispanics. We include these specific details in an effort to show the heterogeneity and sometimes contradictory information present within the existing data, as well as the need to modify research methodologies to be more inclusive of Hispanics.

Additionally, this review provides a brief background in immigration history, socioeconomic status (SES) factors, psychosocial characteristics, and other information concerning the Hispanic population not often learned by healthcare professionals in their education or training. Understanding the diversity among Hispanics may (1) help promote cultural sensitivity and competency, which is important in addressing the burden of CVD in the Hispanic population; (2) clarify the need for disaggregation of Hispanic subgroup categories in the health research and academic literature; (3) better inform the relationship of CVD/cardiovascular health (CVH) in the US Hispanic population; (4) impact intervention and future study design; and (5) improve the understanding of factors that contribute to health disparities for US Hispanics.

Who are US Hispanics? Demographics and SES

The 1970 census introduced the term Hispanic to refer to individuals of any race who have origins in Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, South America, or other Spanish-speaking countries.4,5 The term Hispanic was institutionalized in 1976 when the US Congress passed Public Law 94-311, which mandated the collection of information about these same populations. The term Latino has grown in popularity recently and has been adopted as a term by some members of the Hispanic community (similar to the origins of the term African American). Hispanic and Latino are often used synonymously and interchangeably. Both terms are uniquely American labels.6 However, with increased globalization of Spanish language media in the United States and abroad, Latin America has begun to adopt (or least become familiar with) the terms Hispanic/Latino in reference to a broader Spanish-speaking population. For the purposes of this report, the term Hispanic will be used from here forward. The use of Hispanic throughout this report refers specifically to US Hispanics.

It is also important to note that among Hispanics, the term Hispanic is preferred over Latino by a 2 to 1 margin; however, an overwhelming majority (88%) also prefer to identify themselves with their country of origin.7 Because Hispanic groups and subgroups (by various backgrounds of origin) have different sociocultural practices, environmental experiences, genetic backgrounds, and cultural histories that shape their predispositions to certain chronic conditions, including CVD, the use of the aggregated label of Hispanic likely leads to misclassification with respect to true associations with CVD risk factors and incident disease. In recognition of these differences, as well as the growing relevance of these diverse Hispanic subgroups to national public health, there have been increasing efforts (including the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s HCHS/SOL, the National Eye Institute’s Los Angeles Latino Eye Study, the National Cancer Institute’s Understanding and Preventing Breast Cancer Disparities in Latinas, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities’ San Diego Partnership to Reduce Diabetes and CVD in Latinos) to explore disease risk factors among the different Hispanic subgroups.8,9 Such studies provide an opportunity to examine unique risk factors in collective and disaggregated Hispanic groups. The HCHS/SOL is, to date, the largest cohort study of CVD in US Hispanics, with 16 415 Hispanic participants aged 18 to 74 years who self-identified as being of Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican and Dominican, or Central and South American descent in 4 US communities: Bronx, NY; Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; and San Diego, CA.8,9

Current Demographic Profile

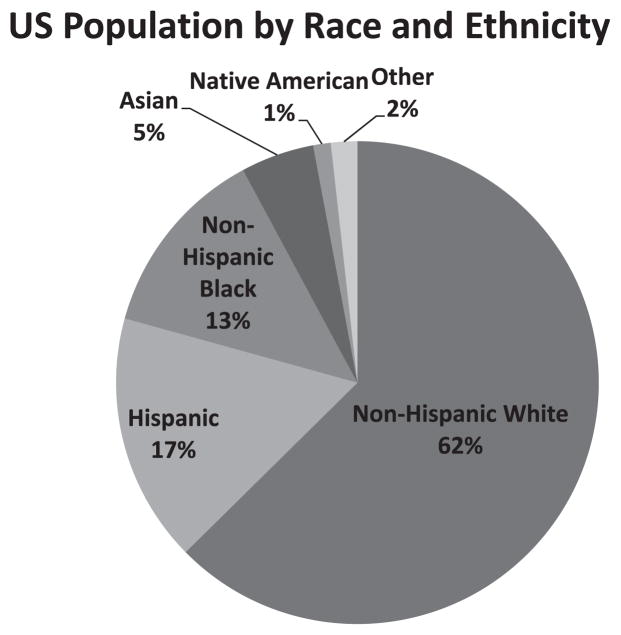

In 2013, 53 million Hispanic individuals represented 17% of the US population, which made them the largest racial/ethnic minority in the United States (Figure 1).10 Moreover, between 2000 and 2010, the Hispanic population increased by 3%, which represented more than half of the nation’s population growth during that decade. Hispanic individuals also represent the largest US immigrant population; among the nation’s 40 million immigrants, nearly half (47%) are Hispanic. A large majority of Hispanic people (74%) are US citizens, either naturalized or by birth.11 Most Hispanic immigrants who were US residents as of 1990 or later (83.6%) had not yet obtained US citizenship by 2011,12 and thus, it is reasonable to anticipate increasing numbers of Hispanic citizens in the future as this recent immigrant population becomes naturalized. Because of the sensitivity of immigration status, data are very limited for unauthorized immigrants, a fact that limits any research on the US Hispanic population.13 Thus, data presented on foreign-born Hispanics residing in the United States may not include those who are not legal immigrants.

Figure 1.

US population by race and ethnicity. Racial groups include only non-Hispanics. Hispanics may be of any race. Source: Tabulations of US Census Bureau Statistics; 2012 population estimates.10

Projected to grow to 30.2% of the US population (132.7 million) by 2050, Hispanics are one of the country’s fastest-growing populations.14 The 2050 projected growth for each Hispanic subgroup will likely vary substantially, as it did from 2000 to 2010 (Table 1). Mexicans increased by 54% and accounted for ≈75% of the 15.2 million person increase in the US Hispanic population. Puerto Ricans grew by 36%, whereas the Cuban population increased by 44%.

Table 1.

The 10 Largest US Hispanic Groups by Origin, 2000 and 2010

| 2000, in Millions | 2010, in Millions | % Change 2000–2010 | % of Total Hispanics, 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombian | 0.47 | 0.97 | 106 | 1.9 |

| Cuban | 1.2 | 1.8 | 44 | 3.7 |

| Dominican | 0.76 | 1.5 | 97 | 3.0 |

| Ecuadorian | 0.26 | 0.67 | 73 | 1.3 |

| Guatemalan | 0.37 | 1.1 | 197 | 2.2 |

| Honduran | 0.22 | 0.73 | 231 | 1.4 |

| Mexican | 20.6 | 31.8 | 54 | 64.9 |

| Peruvian | 0.23 | 0.61 | 165 | 1.2 |

| Puerto Rican | 3.4 | 4.6 | 36 | 9.2 |

| Salvadoran | 0.66 | 1.8 | 172 | 3.6 |

Forty-seven percent of Hispanics aged ≥18 years were married; 36.1% were never married.17 By comparison, non-Hispanic whites (NHWs) of the same age were somewhat more likely to be married (55.4%) and less likely never to have married (23.6 %).17 Foreign-born Hispanic women were more likely to be married (56.2%) than US-born Hispanic women (38.8%).18 Hispanic households are generally larger, consisting of 3.4 people on average, compared with 2.5 people in NHW households.19 Compared with NHWs, a larger proportion of Hispanics are young. The median age of Hispanic individuals residing in the United States was 27 years, which is 10 years younger than the median age of the US population.15 Among Hispanic individuals, those of Mexican background had the lowest median age (25 years) and Cuban Americans the highest (40 years).15 Only 6% of Hispanics people are ≥65 years of age compared with 15% of NHWs. Of note, the aging growth trend is greater for Hispanic individuals than for NHW Americans. That is, although the NHW population aged >65 years is expected to grow by 83% between 2000 and 2030, Hispanic individuals of this same age group are projected to grow by 328%. This makes Hispanics the fastest-growing aging population in the United States,20,21 with potential implications to healthcare costs for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The geographic distribution of the US Hispanic population has also changed substantially within the past decade. Although more than half of all US Hispanic individuals live in 5 states (California, Texas, Florida, New York, and Illinois), the Hispanic population in 8 states in the South (Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee) and South Dakota more than doubled in size between 2000 and 2010.22 South Carolina has the fastest-growing Hispanic population, increasing from 95 000 in 2000 to 236 000 in 2010 (a 148% increase), whereas Alabama showed the second-fastest rate of growth at 145%, increasing from 76 000 to 186 000.

SES Characteristics

Lower SES is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,23,24 possibly related to people with lower SES being exposed to more frequent and severe psychosocial stressors,25 as well as via reduced healthcare access and worsened preventative healthcare practices. According to the US Census, the SES of Hispanic individuals is comparable to that of non-Hispanic blacks (NHBs) and significantly lower than that of NHWs,26 regardless of a variety of SES measures, including personal and family income, poverty rates, educational attainment, occupation, and wealth.

Education

Education has been shown to be the most reliable socioeconomic predictor of CVD.27 In 2000, 53.2% of all Hispanic individuals had an educational attainment of high school or greater, compared with 90.1% of the US population as a whole.28 In 2010, 62.9% of Hispanic adults aged ≥25 years had obtained at least a high school degree and 13.9% had completed at least a bachelor’s degree compared with 87.1% and 29.9% of the total US population, respectively.29 Despite this increase in educational attainment over time, Hispanics had the lowest percentages of those with at least a high school diploma (60.9%) compared with NHWs (90.4%) and NHBs (81.4%).30 Many Hispanic immigrants have received little or none of their education in the United States; however, according to 2012 statistics, first- and second-generation US-born Hispanics complete all of their education in the United States and are generally the first in their families to graduate high school or attend college.31 Furthermore, educational attainment differed by nativity, with foreign-born Hispanics having less educational attainment than US-born Hispanics regardless of Hispanic subgroup. In fact, the educational attainment of foreign-born Hispanics remained lower than all other US racial/ethnic groups.30

Income and Wealth

In 2011, 25.3% of the Hispanic population lived below poverty level compared with 15% of the total US population.32 Between 2006 and 2010, the poverty rate among Hispanics increased by 5%, more than for any other US group. In contrast, poverty rates decreased among NHWs from 10.4% to 9.9% and increased among NHBs by 2.3%, from 25.3% to 27.6%.33,34 The proportion of Hispanic families with annual income >$50 000 was 37.9 % compared with 50.1 % for the total population.32 Approximately 50.9% of Hispanic families have total income <$35 000 per year compared with 26.3% of NHW families.35 Notably, Puerto Ricans on the US mainland face some of the highest rates of poverty seen among all racial/ethnic groups.21,36

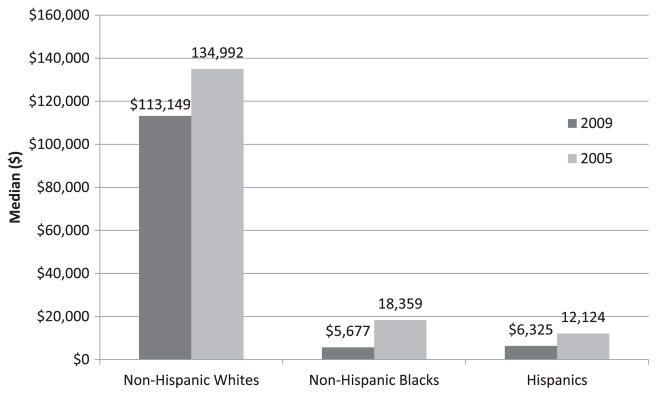

The housing crisis and economic recession between 2005 and 2009 affected the wealth profile of minorities more than the NHW population. In 2009, the median wealth (assets minus debts) of NHW households was 18 times that of Hispanic households. Median wealth between 2005 and 2009 decreased substantially for both Hispanic and NHB households (by 66% and 53%, respectively) compared with the 16% decline in wealth for NHW households (Figure 2).37 These wealth differences by race/ethnicity highlight a greater margin of inequity than seen when household income is compared across groups, because income is distributed more evenly across groups.38 Very little research has examined the impact of income versus wealth inequity on cardiovascular outcomes among the Hispanic population.

Figure 2.

Pew Research analysis of median household wealth across racial and ethnic groups, from 2005 to 2009. Data derived from Pew Research Center tabulations of survey of income and program participation data.37

Occupation

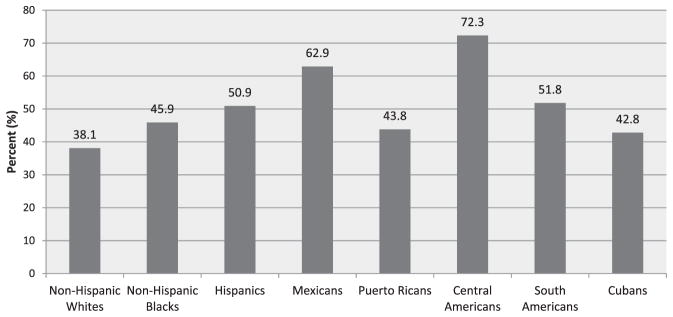

The majority of Hispanics in the United States are employed (66.4%), similar to the 64.0% rate for NHWs.39 Despite this, Hispanic workers have the lowest median earnings of all US racial and ethnic groups.40 The 2 major occupation categories41 are high-risk/low-social-position occupations (including service occupations; precision production, craft, and repair occupations; operators, fabricators, and laborers; and farming, forestry, and fishing occupations) and low-risk/high-social-position occupations (including both managerial and professional occupations and technical, sales, and administrative support occupations). In 2010, Hispanics (59.0%) were disproportionately represented in high-risk/low-social-position occupations compared with NHBs (45.9%) and NHWs (38.1%; Figure 3).42 Because of lower levels of education, limited English proficiency, and documentation status, foreign-born Hispanics are more likely to be employed in low-skill jobs and to have substantially lower incomes than their US-born counterparts.43–45

Figure 3.

Percent composition of racial and ethnic groups in high-risk/low-social-position occupations. Source: Tabulations of US Census Bureau statistics.42

Insurance Status

Access to healthcare services in the United States is highly dependent on availability and access to health insurance. Those who lack insurance either must independently pay for healthcare services or seek healthcare services from safety net facilities such as free clinics, hospital emergency rooms, and community health centers. Because uninsured rates are higher among people with lower SES, and a large proportion of the Hispanic population lives in poverty, a large proportion of Hispanics lack healthcare insurance coverage. In 2011, Hispanics disproportionately represented 30.1% of the US uninsured population and fared worse than NHWs (11.1%) and NHBs (19.5%) with regard to being uninsured.32 Employment does not necessarily guarantee insurance. Although Hispanics are employed at similar rates as NHWs, they are disproportionately uninsured compared with their NHW peers because of their more frequent employment in occupations that do not provide health insurance. The proportion of uninsured Hispanics directly influences their access to health care.

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is anticipated to substantially increase the number of US citizens and legal immigrants with health insurance by expanding Medicaid eligibility to adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level. Although millions of uninsured US Hispanics will be eligible for coverage under the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, undocumented immigrants will continue to be ineligible for coverage under its provisions. Noncitizens or undocumented immigrants who lack continuous, comprehensive, and preventive care will continue to depend on episodic or emergency healthcare services.

Not only are Hispanics at a disadvantage because of low insurance coverage, but research by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also shown that Hispanics are twice as likely as NHBs and 3 times as likely as NHWs to lack a regular healthcare provider.46 One in 3 Hispanic adults in the United States lacks a regular healthcare provider, regardless of nativity status (US born or foreign born).46,47 The profile of a Hispanic individual most likely to lack a regular healthcare provider is similar to that of the general US population without health care: male, young (between ages 18 and 29 years), and less educated (with less than a high school diploma).47 Although Hispanic women are more likely to have a regular healthcare provider than their Hispanic male counterparts (36% versus 17%, respectively), Hispanic women remain less likely to have a usual source of health care (80.0%) than NHW women (91.7%) and all US women (89.6%).47,48

SES Heterogeneity

SES varies significantly among US Hispanic groups (Table 2). Hispanic individuals of Cuban and Puerto Rican background had the highest proportion with at least a high school diploma, and those of Colombian and Peruvian origin had the highest proportions with a bachelor’s degree or more education and the highest median household income. Hispanic individuals of Dominican, Honduran, Mexican, and Puerto Rican backgrounds are among the groups with the lowest median household incomes and are more likely to live in poverty.

Table 2.

Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics for Hispanics, 2010

| Median Age, y | High School Diploma, % | Bachelor’s Degree or More, % | Without Health Insurance, % | Living in Poverty, % | Median Household Income (in Thousands) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombian | 34 | 27 | 32 | 28 | 13 | 49.5 |

| Cuban | 40 | 29 | 24 | 25 | 18 | 40 |

| Dominican | 29 | 26 | 15 | 22 | 26 | 34 |

| Ecuadorian | 31 | 26 | 18 | 36 | 18 | 50 |

| Guatemalan | 28 | 22 | 8 | 48 | 26 | 39 |

| Honduran | 28 | 26 | 10 | 50 | 27 | 38 |

| Mexican | 25 | 26 | 9 | 34 | 27 | 38.7 |

| Peruvian | 34 | 27 | 30 | 30 | 14 | 48 |

| Puerto Rican | 27 | 30 | 16 | 15 | 27 | 36 |

| Salvadoran | 29 | 24 | 7 | 41 | 20 | 43 |

| All Hispanics | 27 | 26 | 13 | 31 | 25 | 40 |

Data derived from Motel and Patten.15

Racial Admixture and Inclusion History Among US Hispanics

Race as a social or biological construct has important CVH implications. Hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and cardiovascular disparities are more prevalent among NHBs than NHWs,49–51 yet race among Hispanic subgroups remains largely unexplored. Hispanics with greater African admixture may have more similarity to NHBs with regard to CVH and CVD risk factors than appreciated previously. Studies suggest that Hispanics of Caribbean descent have a similar prevalence of hypertension,52 abnormal 24-hour blood pressure,53 and cardiac hypertrophy54 as NHBs. Furthermore, some Hispanics may be at risk for not only ethnic discrimination but also racial discrimination because of their non-European appearance.55–57 Research exploring these constructs reported that dark-skinned US Hispanics experience more discrimination than their light-skinned counterparts.58,59 The interaction of darker skin color and SES among Puerto Ricans was associated with higher systolic blood pressure than genetic ancestry alone.60 This section examines some of the rationale that contributes to a greater attention to racial admixture and ethnic group disaggregation among US Hispanics.

Histories of Race in Latin America

Latin America is a region in which extensive racial and cultural mixing occurred through a process of colonization that began in the 15th century. Slavery was abolished in most Latin American countries and interracial marriage was legal and socially accepted by the 1800s, which resulted in an intermixed Latin America.61 As a result, Hispanics are not just geographically and culturally diverse but also racially diverse.62 Specific Amerindian populations differed throughout Latin America so that, for example, the Amerindian population in Mexico is distinct from the indigenous population in the Caribbean, Peru, or Guatemala.63 These indigenous populations shrunk to less than half of their size before Spanish conquest in some Latin American countries and became nearly became extinct in others.64 Countries such as the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Brazil, Panama, Colombia, and Venezuela imported larger numbers of West African slaves, and intermixed populations of African descent constitute a sizeable segment of the Hispanic population in these respective countries. Not only did the size of the Amerindian or African population vary across Latin America, but the practices of intermarriage also varied substantially depending on region and country. Genetic studies have confirmed that Mexican-origin Hispanics have varying proportions of European and Amerindian ancestry, whereas Hispanics from the Caribbean have varying proportions of European and African ancestry.65,66 Central/South Americans have varying proportions of European, Amerindian, and African ancestry depending on the country of origin. Thus, the Latin American country of origin does correspond somewhat to the racially admixed background among Hispanics.63 Asian immigrants have embraced Hispanic culture, intermarried, and made a notable impact on Latin American society. There is also a large population of Chinese ancestry in the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Panama that has existed since migration to Latin America began in the 19th century. Four and a half million Latin Americans (almost 1% of the total population) are also of recent Asian descent. A significant number of Japanese, along with East Asian Indians and Southeast Asians, have established residency in certain countries, notably Paraguay, Argentina, and Peru.

This long history of cultural and racial admixture in Latin America has resulted in a sociocultural, sociopolitical structure that categorizes and recognizes race differently from how race is conceptualized within the United States. Consequently, the accurate identification of race among US Hispanics is problematic. Whereas the racial classification system prominent in the United States reflects only a black or white, Latin America has racially mixed categorizations that are more complex and more closely representative of mixed Amerindian-European or African-European heritage.58,67–69

Immigration/Inclusion Patterns of Different Hispanic Subgroups

Ten Hispanic subgroups represent 92% of the total US Hispanic population (Table 1). There is a distinct and diverse pattern of immigration and inclusion into the United States among each Hispanic subgroup. This, in turn, has had a significant impact on the concentrations of these groups in different US geographic areas, as well as an influence on their health-related characteristics. In broad terms, 4 sociopolitical profiles21 exist among US Hispanics: (1) US born and US educated (includes first-generation* or higher Hispanic people born to immigrant parents; Puerto Ricans; and Mexicans from annexed portions of the Southwest United States); (2) educated professionals who immigrated to the United States, some from large urban cities from Latin America; (3) other documented immigrants; and (4) undocumented immigrants. Profiles 2, 3, and 4 include those immigrants who moved for better economic or educational opportunities or as political refugees. Notably, generational distinctions add to the complexity of Hispanic identity; for example, within the first generation of immigrants, there are fundamental differences between those who arrive as children and those who arrive as adults.70,71 Such generational categories have been found to have direct implications for language, literacy, and economic earnings and consequently, the demographic characteristics associated with health outcomes.70–72

Mexico

Compared with other Hispanic subgroups, Mexican-origin Hispanics probably have the oldest history with the United States. The first era, from 1520 until 1821, covers the period from the Spanish colonization until the beginning of Mexico’s revolution against Spanish rule. A cultural synthesis (mestizaje) of European and indigenous Amerindian cultures took place during these 300 years. During this same period, what is now the Southwest United States was part of Colonial New Spain and later became Mexico when Mexico won its independence from Spain. The second era began in 1822 and ended in 1848 with the Mexican-American War. As a result of that war, the United States annexed the Mexican territories and the inhabitants of what is now the Southwest United States, including California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Texas, Arizona, Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. Large-scale urbanization and industrialization, occurring between 1849 and 1920, marked a third era. The lure of employment opportunities during the labor shortages of World War I, as well as the opportunity for escape from the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917) ensured a steady stream of millions of Mexican immigrants until the Great Depression of the 1930s. When the United States entered World War II, it turned to Mexico to address wartime labor shortages. The Bracero program (1943–1964) allowed for the temporary importation of contract laborers from Mexico and marked a fourth era of immigration from Mexico to the United States. In the decades after World War II, Mexicans’ migration shifted to longer-term settlement patterns, and Hispanic individuals of Mexican background began to emerge as a distinct and visible social group in the United States. This marked the beginning of the fifth era with the passage of immigration reforms in 1965, including legalization programs for those who had entered the United States before 1982. Indeed, by the early 1990s, >90% of Mexican Americans were living in or near urban cities and assimilating to the dominant cultural norms.73 Monolingual speakers of indigenous languages now represent a growing number of the more recent immigrants from Mexico.

Puerto Rico

Whether they were born in their homeland, Borinquen (the indigenous name of the island colonized by Spain in the 1400s), or in the US mainland, Puerto Ricans are citizens of the United States by birth. Some 4.6 million Puerto Ricans live in the mainland United States, and 3.9 million live in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico was ceded to the United States by Spain in 1898 after an invasion of American forces and subsequent defeat during the Spanish American War.

Puerto Ricans began a northward migration in the late 1940s and 1950s as part of Operation Bootstrap after World War II. In an effort to improve the island’s severe economic problems, Puerto Rico prompted a migration of thousands of Puerto Ricans into the agricultural farmlands and manufacturing centers of the northeast United States. The plan had mixed results. Despite their status as citizens, both mainland and island-dwelling Puerto Ricans continue to face tremendous economic challenges. Although the mainland Puerto Rican population has historically been concentrated in the New York/New Jersey/Connecticut area, an increasing number of individuals of Puerto Rican background can also be found in Florida, Illinois (Chicago), and Massachusetts.36

Cuba

The oldest wave of migration of Cubans to the United States can be traced back to the 1800s. When the Ten Years War (1868–1878), a Cuban attempt to become independent from Spain, failed and resulted in a more oppressive Spanish rule, thousands of Cubans left the island and went to nearby Florida. Cuban immigration to the United States continued into Florida and reached new heights between 1896 and 1910, after 1918, and during the Great Depression with the fluctuations of the Florida cigar-making industry. During the Batista regime and before the arrival of Castro’s government, many Cubans fled to Florida in political protest.74 Once the Cuban revolution ended and Fidel Castro rose to power in 1959, some Cubans initially returned to their country in hopes of a better government, but by the early 1960s, the period of modern Cuban emigration began. During this time, Cubans who had their livelihood taken by the government, faced incarceration, or had their freedom of speech repressed, left the island seeking political and economic freedom in the United States. During the same period (1960–1962), >14 000 unaccompanied Cuban youths arrived in the United States; Operación Pedro Pan was the largest recorded exodus of unaccompanied minors in the Western Hemisphere.75

Before 1985, the US government facilitated Cuban immigration with the 1966 Cuban Refugee Act and offered financial support and educational training to facilitate economic and social adaptation into US culture with a degree of acceptance and assistance that no other Hispanic group has experienced. However, this unrestricted immigration changed with the 1980 Mariel Boatlift, which brought 125 000 Cubans, many of whom had been imprisoned for opposition to the Cuban government and called antisocial, to the United States.76,77 This new wave of immigrants faced more discrimination and SES difficulties than previous Cuban immigrants. The US government sought to reduce the number of Cuban immigrants allowed into the United States with the 1980 Refugee Act. In 1984, Congress reenacted the Cuban Refugee Act of 1966 and restored the favorable status Cuban refugees had previously enjoyed. By the end of 1985, most Cubans had received permanent residency status in the United States, which enabled them to apply for citizenship.73

Dominican Republic

Since the early 17th century, the island La Española has been divided into 2 sides, 1 colonized by the French (Haiti) and 1 by the Spanish (Dominican Republic). During the period of colonization, many of the indigenous Caribbean Amerindian population of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic died. By the end of the 17th century, Spanish law allowed slaves in the Dominican Republic to buy their own freedom. As black freemen in La Española began to outnumber slaves, they began to intermarry with Spaniards. This intermarriage has created, over several hundred years, a large mixed-ancestry population and a synthesis of mostly Spanish and African cultures.

The first wave of emigration from the Dominican Republic to the United States was in large part the product of political and social instability in 1963 after a US-supported military coup of the dictator Rafael Trujillo. Those who opposed the new regime and those who were fleeing violence throughout the 1960s came to the United States in notable numbers. Before this time, the possibilities for leaving the island had been very limited. As such, at the time of the 1980 US Census, only 6.1% of all Dominicans had arrived in the United States before 1960.78 Even as the political situation in the Dominican Republic stabilized over time, Dominicans continued to emigrate, mostly because of limited employment and poor economic conditions on the island. Dominicans now account for 3% of the total US Hispanic population, increasing by 85%, from 765 000 in 2000 to 1.4 million in 2010.22 Thus, relative to other Hispanics, the Dominican community is primarily composed of recent immigrants over the past 30 to 40 years. Most Dominican-origin individuals have settled in the Northeast, primarily in New York City, but growing numbers are now found in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Florida, and across the United States.80

Central and South America

Immigrants from both Central and South America began arriving in larger numbers in the 1970s when those countries suffered political instability, economic turmoil, and violence.44 For example, during the 1980s and 1990s, approximately 1 million refugees from El Salvador sought asylum in the United States. In the 1980s, the Guatemalan government began a process of modernizing their indigenous population in an attempt to unify a country divided by >20 different languages, traditions, and religious practices. In this process, the military clashed with local resistance groups and forced many indigenous people, mostly women and children, to cross the border into Mexico or seek asylum in the United States. Similar political turmoil also motivated migration from South America. Although small numbers of Ecuadorians began entering the United States on tourist and work visas during the 1960s and 1970s, most Ecuadorians now living in the United States are economic refugees who fled during Ecuador’s political and banking crisis of the 1990s. These also include a large number of undocumented workers from the rural Andes who work in low-paying, unskilled service and manufacturing industries.

In contrast to their South American peers, Peruvian immigrants began migrating to the United States during the California Gold Rush (1848–1855).81 After World War II, migration increased in response to rising US demand for industrial labor. During the 1970s, mostly upper- and middle-class Peruvian residents, as well as highly skilled professionals and technicians, fled the military regime. In the early 1980s, political violence and economic crisis spurred indigenous people from rural regions and individuals of lower SES to leave Peru. Intensification of violence and the economic crisis, which continued through the 1990s, also forced highly educated, middle class, and professional Peruvians to emigrate.

In general, Central American and South American immigrants are more recent additions to the United States. In recent decades, the Central American population in the United States has grown rapidly, from 345 655 in 1980 to 1.1 million by 1990 and nearly doubling to 2.0 million in 2000. Similarly, the Central American immigrant population grew by nearly 890 000 between 2000 and 2009, and by 910 000 during 1990 to 2000.43 Immigrants from El Salvador and Guatemala accounted for 41.2% and 28.7%, respectively, of the total increase. Although Colombian immigrants are relative newcomers, Colombians were the largest South American immigrant group in the United States in 2010, accounting for 23% of all South Americans in the United States.82 Central Americans from Guatemala and Honduras are more likely than any other US Hispanic group to lack health insurance.

Documenting Race Among US Hispanics

The histories of migration, immigration, and the processes of colonization have resulted in unique racial admixture among Hispanics. Hispanics can be of any race or combination of races and may self-identify as Asian, Amerindian, black, or white, but in the United States they are all considered Hispanics. Despite this reality, the US Census defines race by 6 categories: NHW, NHB, American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, and Other; ethnicity is only subdivided as Hispanic or non-Hispanic. The discordance between the understanding of race among Hispanics and the US conceptualizations of this construct affects how Hispanics respond to the discrete racial categories that appear on the US Census. Among Hispanics, the question of race in the United States is frequently confused with that of ethnicity. There is a perception that for Hispanics to identify as racially black or white in the United States, they are negating their ethnic Hispanic identity. Moreover, acculturation among Hispanics, which is dependent on length of time in the United States, age of arrival, immigrant generation, educational levels, and even geographic residence, also influences understanding of the US racial taxonomy.83,84 As a result, national attempts at racial data collection among Hispanics have often been unfruitful, revealing little about this population. A growing proportion of Hispanics self- identify as “other race.”67,85,86 Yet it would be incorrect to merge the concepts of race and ethnicity when it comes to Hispanics.87–89 What is needed is better educating of Hispanics on the societal differences of the concept of race between the United States and Latin America and on what can be learned from racial self-identification under the current US framework.

Genetic admixture analysis is another method to investigate potential genetic factors that contribute to racial differences in complex phenotypes.90,91 The technique is based on the knowledge that individuals can be classified, on the basis of genetic markers, into clusters that correspond to continental lines and to commonly identified racial groups. Genetic admixture analysis quantifies the proportion of an individual’s genome that is of a given ancestral origin (eg, European, African, Asian) using ancestry-informative markers (those with large frequency differences between the ancestral populations). Genetic admixture analysis may provide a more sophisticated and informative method of studying race and the ways in which race affects CVD among Hispanics, rather than the cruder self-reporting into categorical racial groups.65,66,92

Commonalities in Language and Cultural Beliefs Among US Hispanics

Although Hispanics are not bonded by shared physical characteristics, the fusion of Spanish, African, and Amerindian culture, religion, and histories has given rise to a rich cultural heritage, an intertwined history, a common language,93 and several cultural characteristics that are common across the varied Hispanic subgroups, including familismo, respeto, personalismo, simpatía, personas de confianza, religiosidad, fatalismo (destino).94

Language

Spanish is the predominant language throughout Latin America (except for Brazil) and has had far greater generational longevity than other non-English languages in the United States.95 A continuous flow of Latin American immigrants makes it easier for US Hispanic residents to retain their Spanish tongue and provides greater opportunities and incentives for bilingualism.95 The spoken Spanish language varies among diverse Hispanic subgroups, and slight regional variations in Spanish dialect and accents are present across Latin America. Among a minority of foreign-born Hispanics, particularly migrant workers from some rural parts of Mexico and South America, indigenous languages such as Mixtec, Chinantec, and Mayan are more common; limited formal Spanish literacy skills and lack of written indigenous languages are further significant barriers to healthcare services, education, and other social services.96,97 Although proficiency in English is often a measurement of acculturation, its use among US Hispanics is influenced by multiple factors, including generational patterns, SES, sex (more so in females), and family communication dynamics.98 Preference for and ability in the English language vary widely among Hispanics. Among many Hispanics, English is commonly used for business and official domains, as a means of achieving social mobility, whereas Spanish is used mostly in familiar and personal environments.99,100 Among US-born Hispanics, according to self-report, 38.7% spoke only English and 61.2% were bilingual, of whom 12.2% spoke English less than “very well.”101 Foreign-born Hispanics are mostly a population with limited English proficiency; 4.2% spoke English only, and 95.8% were bilingual, of whom 68.4% spoke English less than “very well.” By the second and third generations, estimates of English fluency jumped to 88% and 94%, respectively.102 Immigrants who arrived in the United States as young adults are more likely to report not speaking/reading English well than those who arrived before the age of 10 years.102 Furthermore, English language proficiency may differ across Hispanic subgroups. A recent Pew Hispanic Center report found that Hispanics of Mexican and Puerto Rican backgrounds had the highest proportions of individuals who spoke only English at home, whereas those of Dominican, Guatemalan, Honduran, and Salvadoran background had the smallest proportion of English-proficient speakers.15

Among Hispanic populations, language preference and proficiency have profound effects on health services utilization, perception of healthcare quality, and even risk of poor health.103–105 In the 2003 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, speaking a language other than English at home identified Hispanics who were at risk for not receiving recommended healthcare services.106 However, researchers using the BRFSS noted that Spanish-speaking Hispanics ate fruit more times per day but consumed significantly fewer vegetables than English-speaking Hispanics.107

Preference for and use of the Spanish language influenced perceived health status, as well as health knowledge. BRFSS data (2003–2005) from 45 076 Hispanic adults in 23 states showed that Spanish-speaking Hispanics reported far worse health status and less access to preventive health care than did English-speaking Hispanics; these findings were not attenuated by adjustment for SES factors.103 Furthermore, these data showed that although almost half of all Spanish-speaking Hispanics had a personal physician, 1 in 4 were unable to afford needed health care in the past year and were less likely to receive preventive health services.105 Spanish-speaking Hispanics were far less likely to be knowledgeable of heart attack and stroke symptoms than English-speaking Hispanics, NHBs, and NHWs.108

Language and Health Literacy

There is an important role for health literacy, because it influences the ability to negotiate health systems, understand and act on health treatment and advice, and seek timely and appropriate health care.77,78 Lower health literacy predicted increased all-cause mortality among patients with heart failure.109 Although low health literacy can impact all populations, health literacy is particularly relevant for Hispanics. The education, income profile, and English proficiency characteristics of the Hispanic population heighten the health literacy challenges. There are 3 aspects of health literacy: (1) Functional health literacy refers to basic skills in reading, writing, and comprehension, and some research has indicated that health disparities are attenuated by increasing functional literacy.110 (2) Interactive health literacy focuses on personal skills that increase self-efficacy and motivation. (3) Critical health literacy is defined as a range of skills that enable individuals to obtain, understand, use, and evaluate health information with the goal of reducing their own health risks, exerting greater health decision making, and making informed health choices.111–114 Patient-level health literacy potentially influences a patient’s willingness to engage their physicians in discussions about health issues. Almost twice as many Spanish-speaking compared with English-speaking patients have poor functional health literacy that results in a significantly diminished capacity to function in the healthcare system.115 Moreover, 3 times the number of Hispanics as NHWs lack the functional health literacy required to understand medical instructions and healthcare information such as reading their medication bottles.116 There has been very little examination of the recent accessibility of health information available online or via social media and the health literacy disparities produced or exacerbated because of the “digital divide.”

Language and Patient-Provider Relationships

Language discordance, when patients and providers do not share a common language or have limited proficiency in one another’s languages, is one of the greatest barriers faced by Hispanic patients in accessing health care. Communication challenges include the physician’s inability to listen to everything communicated by the patient, patients not fully understanding their doctor, and patients having questions during the visit that they were unable to ask. These problems are worse among Spanish-speaking patients than among those whose primary language is English.117–119 Often, Hispanic patients with limited English-speaking abilities find translation services to be inadequate and thus question the accuracy of the health information they are receiving.120,121 As a result, these patients often rely on family members as translators.122,123 Even after controlling for SES and demographic characteristics, Spanish-speaking patients report perceived differences in the type and quality of information that clinicians provide and receiving health education information that is less detailed and less empathetic.105,120,124–127 Cultural competence and literacy among providers, a significant factor for effective patient-provider communication, has been linked with improved patient decision making, patient communication, and adherence to treatment.128 Training for providers in cultural competence and cultural literacy includes knowledge and skill development in the use of patient beliefs, customs, and world views to frame health information.129 Provider cultural competence is perceived to be high when the practitioner is able to speak even some Spanish and can affect the content of the interaction.58,67 In these cases, Hispanic patients’ recall of the information exchanged and the patients’ satisfaction with the interaction are high.130,131 One recent study examined the role of culture and healthcare interaction among Mexican immigrants and found that adherence decisions were associated with patients’ beliefs about the physician’s cultural literacy and identity.128

Familism

Familism or familismo is considered an important part of Hispanic culture132 and is characterized when family members are a source of financial or emotional support.133 Foreign-born, less acculturated Mexicans for whom Spanish is the primary language spoken at home have higher family support than NHWs.134 Family members are often a source of financial or emotional support, which in turn can facilitate access to health services,135 promoting preventive practices and better medical treatment adherence. The main elements of familism include the perceived obligation to provide family members with material and emotional support, reliance on family members for assistance, and the perception of family members as attitudinal and behavioral referents.136 Studies on familism suggest that its salutary effects may help explain the better-than-expected health outcomes (ie, Hispanic paradox) observed in Hispanics.137,138 In fact, familism is often the basis for studies on CVD risk factors and social support among Hispanics.

Hispanic families in Latin America have been described as amplified or extended families consisting of a nuclear family and aunts, uncles, cousins, and godparents, as well as non-blood relatives such as friends and neighbors who have grown up together (often referred to as additional aunts, uncles, and cousins) who are also extensions of the family.139 As a result of this strongly held cultural value, Hispanic patients tend to respond better to messages with emphasis on “doing the right thing for the family” rather than “doing the right thing for yourself.”136 A focus on the family enables Hispanic immigrants to retain aspects of their culture, which may protect them from negative behaviors found in the mainstream culture140 and promote better psychological well-being.141 However, familism might attenuate over time as Hispanic immigrants assimilate into the more individualistic US culture. As a result, US-born Hispanics report lower familial social support than foreign-born Hispanics.134 Nevertheless, the attitudes of even more acculturated Hispanics remain more familistic than those of NHWs.142 Because familism can be broadly defined as placing one’s family above oneself, emphasizing interdependence over independence,143 familism can also contribute to stressful situations, particularly during the acculturative process. For example, an individual who agrees that an aging parent should live with relatives may experience distress if he or she is unable to provide such living arrangements for his or her parent(s).

Personalismo

Another characteristic of the Hispanic culture is personalismo, described as a “formal friendliness.”130 The concept suggests that adequate time is taken to establish an intimate and sustained relationship by communicating with patients in an open and a caring manner.130,144 Personalismo repeatedly has been found to be an important element in culturally competent encounters.119 A major aspect of personalismo is respeto, which refers to a tendency to respect generational hierarchies, giving more value to the opinions of elders; it is a broader construct in which respectful behavior toward peers is also important. Respeto influences parenting practices, because Hispanic parents tend to perceive the autonomy and individualism within Anglo-American culture as being in direct opposition to those cultural values of respect and generational deference.145 Similarly, Hispanic patients may not make a decision without having family present when the doctor speaks and may cede autonomy to family members or even to the doctor in important life decisions.

Marianismo and Machismo (Gender Roles)

Among most Hispanic subgroups, gender roles are clearly defined and often originate from the influence of Catholicism. The patriarchal authority characterizes the male role along a spectrum of machismo. On the one hand, machismo carries with it a positive quality of the honorable and responsible man who must always provide for and protect his family, friends, and community. This interpretation of the concept has been used to underpin spouse/partner leadership in risk reduction behavior.146–148 On the other hand, the negative consequences of machismo include domestic violence, infidelity, and high-risk behaviors.146

Matriarchal female roles are very prominent and important in Hispanic culture and are governed by norms conveyed through the concept of marianismo. Marianismo presents an idealized concept in which women are supposed to be virtuous, humble, and spiritually superior to men while also being submissive to the demands of men and to withstand extreme sacrifices and suffering for the sake of the family, frequently prioritizing family responsibilities over self-care.149–151 Hispanic adolescent females generally have positive perceptions of their ethnic background.152 This strong identification of Hispanic gender roles may play an important role in engaging in health behaviors that reduce CVD risk factors.

Faith, Spirituality, and Religious Values

Religion remains an important part of the Hispanic community.153 Ninety-one percent of Hispanics report some religious affiliation, with Roman Catholic affiliation being the most common (56%), although Protestant denominations are embraced by 23%.154 Hispanics value having a sense of spirituality and often prioritize achieving spiritual goals over material satisfaction. As such, Hispanics are often religious, and their way of expressing religious worship is often different from that of the US dominant culture.139 Hispanics are more likely to see a link between body, mind, and spiritual health. A consequence of spirituality is a sense of fatalism or destino in which life experiences, events, and adversities are inevitable and cannot be controlled or prevented. Such thinking leads to the fatalistic attitude that “whatever God wants, shall be” (“lo que Dios quiera”). Fatalistic beliefs have been correlated with a variety of negative health outcomes, including CVD,155 as well as protective factors that reduce drug abuse among Hispanic youths.139,156,157 Because religious networks and norms sometimes help to guide health behaviors, there is evidence that the deployment of interventions at Hispanic churches can serve as a motivating source of health education and fellowship, similar to what has occurred in the NHB community.158,159

Psychosocial Factors Affecting CVD Risks and Health Behaviors

Acculturation

Acculturation is defined as the process of adaptation to a new culture assessed by the integration into the new country’s cultural values, behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes.160 Researchers have categorized acculturation into 4 components,161 as follows: (1) Integration—maintaining attitudes and behaviors from the original culture but also adopting values and behaviors of the dominant culture; (2) assimilation–entirely adopting the values and behaviors of the dominant culture; (3) separation—rejecting the ways of the dominant culture and keeping the cultural practices and behaviors of the original culture; and (4) marginalization—not identifying with the original culture or the dominant/mainstream culture.162 The associated stress of cultural adaptation, as well as the concomitant behavioral changes, renders acculturation a significant explanatory variable related to CVH among Hispanics.163 Within the US Hispanic population, increasing numbers experience the acculturative process to US society, with the potential for a large impact on CVH and CVD risk.

The measurement of acculturation in research is challenging and thus far has been criticized for being too linear, relying heavily on English language use and acquisition and failing to consider the social and cultural experiences, such as living in economically deprived areas or racially/ethnically segregated neighborhoods that modify health behaviors as Hispanics acculturate.162,164–169 Additionally, most acculturation measures do not capture the fluidity of the acculturative process or the psychosocial components, such as vulnerability (eg, stress) or resilience factors (eg, social support), that may operate throughout. Given that several acculturation scales were created for or tested only in individual Hispanic subgroups (eg, the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans II170), they may not capture the diversity of cultures within the Hispanic population and may not be generalizable to other Hispanic subgroups. Measurement of the level of acculturation is also challenging because as the United States becomes more diverse and multicultural, the “mainstream” society becomes more diverse and complex.168,171 The global dissemination and incorporation of Western lifestyle and behaviors throughout the globe further complicate our understanding and measurement of acculturation within the United States.

Despite these difficulties, a wealth of data shows that there are relationships between acculturation and coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factors. Epidemiological studies rely on proxy markers for acculturation, which include English language fluency, place of birth, length of time in the United States, age at time of immigration, generational status, and language spoken at home. Comprehensive reviews of health outcomes show strong negative effects of increasing acculturation on cardiovascular risk factors but positive effects on use of preventive health services, including screening.172–180 Some survey data show worsening CVD risk factors, including obesity, that increase with length of residency in the United States.172,180–182 Additionally, Spanish-speaking, less acculturated Hispanics report less use of preventive healthcare services and poorer heath.103,126,183 For example, among Mexican women, the highly acculturated had higher body mass index (BMI), fat mass, fasting insulin, and diastolic blood pressure than less acculturated women.179

Acculturation and Nutritional Behaviors

A healthy diet is essential to the promotion of CVH and the prevention of chronic illness, yet diet and nutrition are culturally bound. As a result, each Hispanic group has its own distinct nutritional habits and key dishes from its country of origin, based on customs and traditional foods that are readily available in its geographic area. Overall, Hispanic diets tend to be high on fiber, relying heavily on beans and grains. Results from the 2002 BRFSS showed that NHWs consumed a higher percentage of the daily recommended allowance of fruits and vegetables, followed by Hispanics and NHBs (23.4%, 22.9%, and 21.4%, respectively).184 Among Hispanic families, 15.8% have low food security, with less access to nutritious and safe foods.185 The risks associated with food insecurity include poor dietary quality and overweight/obesity.186 Perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes about foods characterize energy intake patterns and are influenced by assimilation of the mainstream culture’s dietary patterns.187 Using nationally representative data, it was shown that US-born Hispanics consumed more unhealthy foods and had greater caloric intake than foreign-born Hispanics.188 Qualitative work suggests that Hispanic immigrants struggle to retain their cultural food traditions and consume more high-fat, high-sugar foods than they did in their home countries.189 Among less acculturated Hispanics, energy intake has repeatedly been documented as more nutritious, with less fat and more fiber consumption, lower in saturated fats and simple sugars; highly acculturated Hispanics eat fewer fruit and vegetable servings.175,190–195 Other reviews suggest that the process of acculturation does not influence food choices among Hispanic subgroups and is not related to percent fat intake or percent energy from fat.195 Inconsistencies in the relationship between acculturation and diet among Hispanics are likely confounded or misclassified because of the variety of measures of acculturation used, potential differences between Hispanic subgroups, and the relationship of SES to food choices and healthy food availability. However, research documenting changing food practices resulting from immigration shows that the primary differences between the United States and the immigrants’ native countries stem from food access: greater amounts of poor quality foods available in the United States, whereas fruits and vegetables are more accessible and more affordable in many Latin American countries.

Acculturation and Acculturative Stress

Acculturative stress, an inability to successfully navigate the immigrant process and make decisions on retaining one’s native culture while adapting to a new culture, may exert a remarkable stress on CVH behaviors and subsequent health risks.196 Recent research shows that problems such as a lack of healthcare access and social marginalization produce significant distress.197–199 Furthermore, as Hispanic individuals attempt to acculturate to the economic, social, and cultural challenges of life in the United States, they experience a high burden of stress, depression, and anxiety.175,200 For some Hispanics, Americanization includes “upstream” contributors to CVD such as an abundance of fast foods, social isolation, and increased sedentary behaviors.201–204

A contributing healthcare barrier for some Hispanics is the belief that a healthcare provider is unnecessary because they are seldom sick.27 Some of this belief originates from the payer structure of healthcare systems in parts of Latin America, along with the perceived complexity of navigating the US healthcare system. Higher levels of acculturation are not only associated with higher levels of insurance coverage, they are also associated with greater use of preventive screening.175,205,206 The mechanism through which healthcare information is obtained may pose an additional barrier to care. Although >25% report obtaining no healthcare information from medical personnel in the past year, >8 in 10 Hispanics report receiving health information from alternative sources, such as television and radio.47

The available data also illustrate the heterogeneity of effects, sometimes conflicting, when one examines the role of acculturation in CVD risk. These conflicting findings suggest that the effects of sociocultural and economic factors should not be examined in isolation.198,207 Cultural and economic assimilation into mainstream society is associated with more positive health perceptions and greater levels of physical activity.172 Healthcare disparities experienced by recent immigrants or those who are less acculturated are underpinned by the lack of insurance, poverty, and legal status.183,201 Furthermore, the increasing consumption of fast foods and the rising burden of obesity globally calls into question the “better” health of immigrants on arrival in the United States.208 Additionally, prevalence rates of adult congenital heart disease and rheumatic heart disease may be higher among immigrant populations, but this has not been well studied.

Perceived Discrimination

Research has shown that perceived discrimination or unfair treatment conceptualized as a form of social stress may be associated with health outcomes.209–211 Most studies that examined perceived racial discrimination and CVH have focused on NHBs,212–214 whereas studies on discrimination among Hispanics have focused mostly on mental health outcomes.215–217 Despite this focus, an association of perceived discrimination with CVH outcomes among Hispanics may also exist.60,218 Prevalence estimates of perceived discrimination (those who experienced some form of unfair treatment attributed to race or ethnicity) among the US Hispanic population is ≈30% to 40% but may vary by Hispanic subgroup and Hispanic race.59,102,219,220 In 1 study, perceived everyday discrimination was detrimental to the physical health of Puerto Ricans and Mexicans, but the stress-buffering effects of marriage attenuated the associations among Mexicans only.221 Another study found that there were no variations between NHBs, NHWs, and Hispanics in the inverse associations of perceived discrimination and self-reported general health.210 Coping mechanisms in response to perceived discrimination among the total Hispanic population or certain subpopulations may have similarities to or differences from those of NHBs, but this has not been studied. Validation of existing perceived discrimination instruments (mostly developed for NHBs) in Hispanics is also needed.

Social Support

Social support is the extent and conditions in which interpersonal ties and relationships are linked to the broader environmental determinants of well-being222,223 and describes both the structure of a person’s social environment (social networks and network adequacy) and the resources such environments provide (financial, instrumental, and emotional support). Social support may influence CVD/CVH factors via the pathways of influencing health behaviors and facilitating adherence to medical regimens.142,224 Social support may also buffer the adverse effects of sociocontextual factors that may contribute to both increased stress and poor cardiovascular outcomes.225,226 Although greater levels of CVD risk factors are linked to lower social support among NHBs,227–229 most studies of social support among Hispanics have inexplicably been limited to the context of physical activity, particularly among Hispanic women.230–234 In pregnant and postpartum Mexican-born women, social support is essential to the maintenance of physical activity, especially compared with women of other ethnic groups.235 Strong networks of social support are hypothesized to be instrumental in influencing Hispanic CVD/CVH outcomes, but further study is needed to support this claim.

Use of Alternative Medicines

The use and influence of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) on adherence to conventional medicine is complex and poorly understood. Part of the complexity stems from the fact that CAMs encompass a broad variety of treatments not typically prescribed by a medical doctor, including (1) the use of vitamins and nutritional supplements or special diets; (2) medicinal herbs or teas, homeopathic remedies, and manual therapies (sobadores); and (3) energy therapies (Reiki, biofeedback), acupuncture, and prayer. Studies suggest that the use of CAMs among Hispanics as a form of health care appears to be because of its affordability, accessibility, and familiarity, as well as concerns of patients that they were not receiving a correct diagnosis or treatment through conventional medical practice.236–238 Often, patients using CAM or folk therapies do not inform their healthcare providers about these practices.239–241 It is common to find treatments that combine CAM and mainstream medicine.242–245 This is a concern because some CAM treatments may interact with prescribed medications,237,246,247 and this can put patients at increased risk, for lack of the expected therapeutic effects or an adverse reaction.245,248

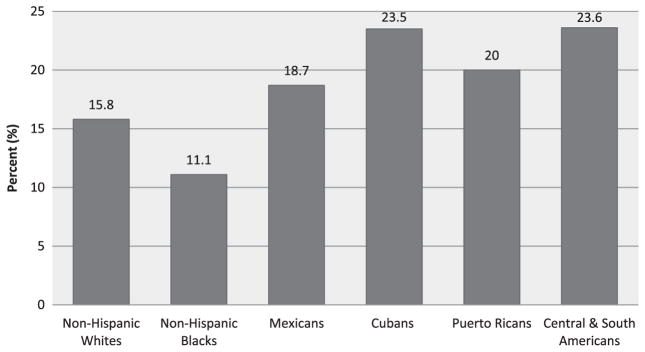

CAM studies among Hispanics reveal mixed findings. Some studies have found lower CAM use among Hispanics compared to NHWs and NHBs or minimal racial and ethnic differences in CAM use, whereas other studies have found that CAM use, particularly the use of herbal teas and plant-based substances, was the most frequently reported treatment among Hispanics.238,240,249–253 A more recent study found that CAM use was lower among NHWs and NHBs than among all Hispanics (Figure 4).254 Some studies have reported lower CAM use among foreign-born Hispanic women compared to US-born counterparts, whereas other studies found that foreign-born Mexicans had higher CAM use.251,255 Such mixed results speak to the limitations of the studies (small sample sizes or administration of surveys in English language only), but they also suggest that CAM use among Hispanics is more complex and nuanced than is currently understood.253

Figure 4.

Recent use of complementary and alternative medicines across racial and ethnic groups. Data derived from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.254

There are several cultural folk beliefs related to the origins of illnesses across diverse Hispanic subgroups that influence the use of CAM.21,256,257 There is a humoral approach to illness/ healing that emphasizes the hot-cold equilibrium in both diagnosis and treatments.183 This is expressed by the folk belief in pasmo (spasm), in which illness or death can be brought on by exposure to cold air when the body is overheated.21 One study found that 70% of the parents of Mexican descent believed in mal de ojo (evil eye), 64% in empacho, 52% in mollera caida (fallen fontanel), and 37% in susto (fright) as folk causes of illness and that 20% had taken their children to curanderos (traditional healers) for treatment of these folk illnesses.258

Prevalence of CVD Risk Factors in Hispanics

In 2010, the American Heart Association declared 2020 health strategy goals to reduce deaths attributable to CVD and stroke by 20% and to improve the CVH of all Americans by 20% by focusing on 7 key risk factors: smoking, BMI, diet, physical activity, blood pressure, blood glucose, and total cholesterol.259 In this section, we review several of these key risk factors with respect to US Hispanics. Hispanics are significantly less aware of CVD as the leading cause of death and their personal risk factors for CVD than are NHWs.260 This is important, because the first step toward prevention is awareness.

As mentioned previously in the limitations to the present report, most of the cohorts referenced below have included predominantly Mexicans as the representative Hispanic population. Despite this limitation, studies do suggest that CVD risk factor prevalence varies across Hispanic subgroups. When available, this review specifies the Hispanic subgroups examined; when Hispanic background group was not specified, we simply refer to the participants as Hispanics.

Traditional Risk Factors

Hypercholesterolemia and Hypertension

According to 2007 to 2010 NHANES data, among Mexicans ≥20 years of age, 48.1% of men and 44.7% of women have total cholesterol levels ≥200 mg/dL (of these, 15.2% and 13.5%, respectively, had levels ≥240 mg/dL), and 39.9% and 30.4% had low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels ≥130 mg/dL.261 Data from the 1982 to 1984 HHANES demonstrate variation in prevalence of hypercholesterolemia (defined by abnormal total cholesterol or LDL-C) among 3 Hispanic subgroups: Mexicans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans. Women in each subgroup had the highest prevalence of hypercholesterolemia, with Puerto Rican women having a prevalence of 20.6%.262 In the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (which included 277 total Hispanics), Puerto Rican women had the highest prevalence of smoking (26.8%) but the lowest mean levels of LDL-C.263 Among 1437 Hispanic participants (56% Mexicans, 12% Dominicans, 14% Puerto Ricans, and 18% Central/South Americans) from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), Mexicans had the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia.264 For HCHS/SOL, the overall prevalence of hypercholesterolemia among Hispanic men was 51.7% and ranged from 47.6% among Dominican and Puerto Rican men to 54.9% among Central American men. Among women, the prevalence of hypercholesterolemia was 36.9% overall and ranged from 31.4% among South American women to 41% among Puerto Rican women.1,265

Despite high prevalence rates of hypercholesterolemia, disparities related to sex and race/ethnicity exist and result in substantially lower rates of treatment and control among Mexicans than among NHWs.266,267 Fewer than half of all Mexicans had been screened for high cholesterol in the previous 5 years compared with 65.2% of NHWs and 57.7% of NHBs, with fewer than half of Mexicans actually being aware that they had high cholesterol.267 The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) found that Hispanics tended to have more mixed dyslipidemia, with lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, higher triglyceride levels, and similar LDL-C levels compared with NHWs.268 This pattern of low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high triglyceride levels is a major risk factor for CVD because of its association with insulin resistance and smaller, dense, more atherogenic LDL-C particles. Adequate screening measures and treatment for this type of dyslipidemia are warranted for Hispanics.265

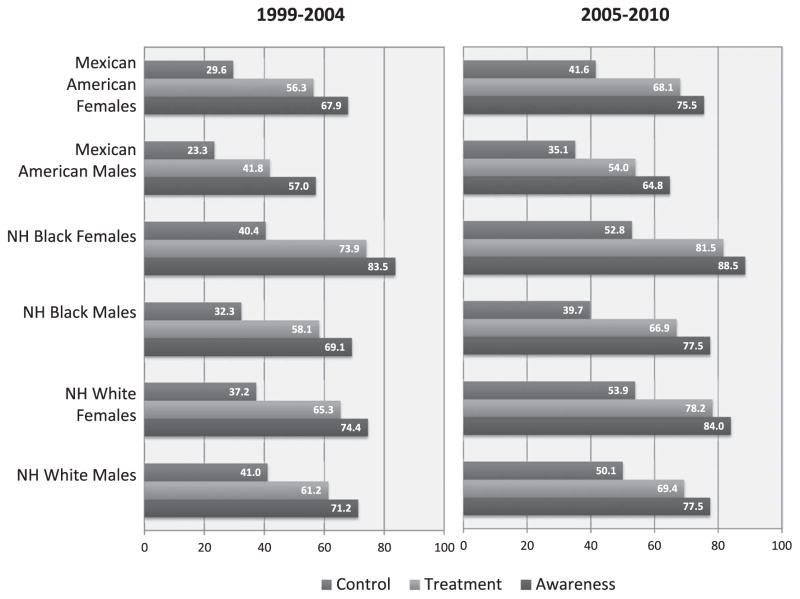

Although hypertension-related mortality rates have increased among Hispanics, and differences by Hispanic subgroup are evident,269,270 there is a remarkable lack of consistent information regarding the prevalence of hypertension among US Hispanics. Studies suggest that the prevalence of hypertension is highest in NHBs and lowest in Mexican Americans.271,272 The prevalence of hypertension among Mexicans (30.1% in males, 28.8% in females) is lower than the prevalence of hypertension in the general American population (33.0%).261 Comparison between NHANES examinations273 conducted in 1988 to 1992 and 1999 to 2000 revealed that among Mexicans, age-adjusted rates of prehypertension increased from 33.2% to 35.1%, rates of stage 1 hypertension increased from 12.4% to 14.8%, and rates of stage 2 hypertension increased from 4.2% to 5.3%. Similarly, the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension among Mexicans increased from 17.2% in 1988 to 1991 to 20.7% in 1999 to 2000 and to 27.8% in 2003 to 2004.271,274 Over a 10-year time span, Hispanic individuals remained more likely to have undiagnosed, untreated, or uncontrolled hypertension than other ethnic groups (Figure 5).276–278

Figure 5.

Rates of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control by race/ethnicity and sex, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999 to 2004 and 2005 to 2010. NH indicates non-Hispanic. Data derived from Go et al.275

Little has been published about the prevalence of hypertension in other Hispanic subgroups. Among NHIS 1997 to 2005 respondents, in multivariate-adjusted analyses that controlled for sociodemographic and health-related factors, odds of self-reported hypertension were 67% higher among Dominicans and 20% to 27% lower among Mexicans/Mexican Americans and Central/South Americans than among NHWs.279 Among Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) participants (predominantly Dominican), objectively measured hypertension was similarly substantially higher in Hispanics (59%) than in NHWs (42%).54 These findings suggest that Hispanics of Dominican origin may be at particularly high risk of hypertension. Among Mexicans ≥20 years of age, 27.8% of men and 28.9% of women have high blood pressure, with Puerto Rican Americans having the highest hypertension-related death rate of all Hispanic-background groups (154.0/100 000) and Cuban Americans having the lowest (82.5/100 000).269 Among foreign-born Hispanics who responded to the NHIS, those of Puerto Rican and Dominican origin had higher hypertension prevalence than those of Mexican origin.280 Among MESA participants, Dominicans had the highest rates of hypertension.264 Similar high rates of hypertension among Dominicans have been documented in HCHS/SOL. The overall prevalence of hypertension among Hispanic men was 25.4%, with the highest proportion among Dominicans (32.6%) and the lowest among South American men (19.9%). Among Hispanic women, the prevalence of hypertension was slightly lower (23.5%) and was highest among Puerto Rican women (29.1%) and lowest among South American women (15.9%).1 In the HCHS/SOL, of those with hypertension, 82% were aware of their hypertension, 50% were receiving treatment, and only 32% of those treated had their hypertension under control.281