Abstract

Immune-mediated adverse drug reactions (IM-ADRs) are an underrecognized source of preventable morbidity, mortality, and cost. Increasingly, genetic variation in the HLA loci is associated with risk of severe reactions, highlighting the importance of T-cell immune responses in the mechanisms of both B-cell mediated and primary T-cell mediated IM-ADRs. In this review, we summarize the role of host genetics, microbes and drugs in the development of IM-ADRs, expand upon the existing models of IM-ADR pathogenesis to address multiple unexplained observations, discuss the implications of this work in clinical practice today, and describe future applications for pre-clinical drug toxicity screening, drug design, and development.

Keywords: abacavir, adverse drug reaction, allopurinol, altered peptide, carbamazepine, DRESS, hapten, heterologous immunity, human herpesvirus, human leukocyte antigen, major histocompatibility complex, p-i, pharmacogenetics, pharmacogenomics, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, SJS, T cell receptor, toxic epidermal necrolysis, TEN

Introduction

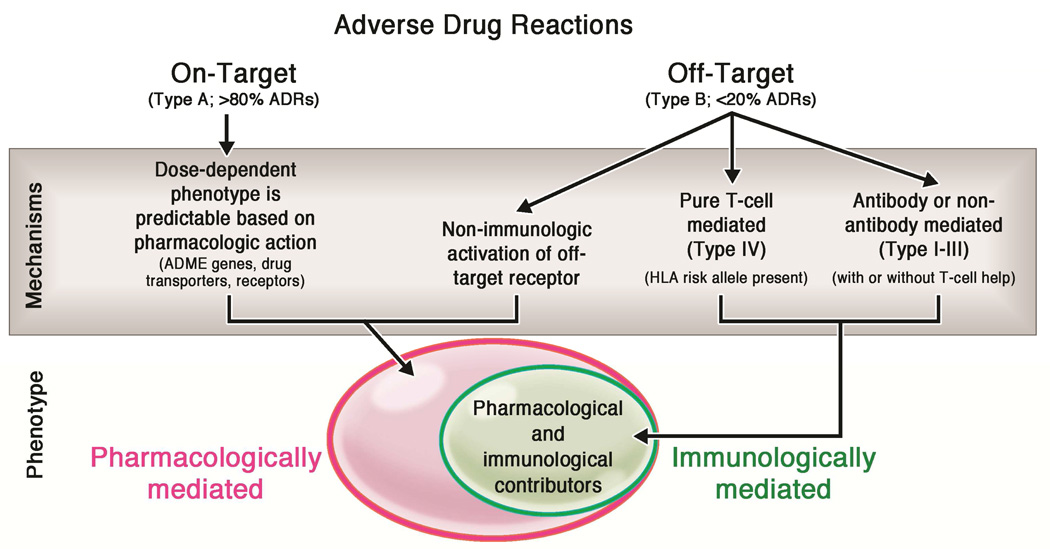

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are sources of major burden to patients and the healthcare system and 50% of such reactions are preventable.1–8 The majority of ADRs are predictable based on the on-target pharmacologic activity of the drug (Figure 1).2,4–7,9,10 Up to 20% of all ADRs are not readily anticipated based on pharmacologic principles alone and, until recently, were considered “idiopathic” and “unpredictable.” We now know that these reactions stem from specific off-target drug activity and include the immune-mediated ADRs (IM-ADRs) as well as off-target pharmacological drug effects such as that seen in non-IgE mediated mast cell activation syndrome (Figure 1).11 IM-ADRs encompass a number of phenotypically distinct clinical diagnoses that comprise both B-cell (antibody-mediated, Gell Coombs Types I-III) and purely T-cell mediated reactions (Gell-Coombs Type IV). The clinically relevant T-cell mediated drug reactions have been classified into delayed exanthema without systemic symptoms (maculopapular eruption or MPE), contact dermatitis, drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS)/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS)/hypersensitivity syndrome (HSS), Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), fixed drug eruption, and single organ involvement pathologies such as drug-induced liver disease (DILI) and pancreatitis. Allelic variation in the genes that encode the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) family of proteins is often associated with risk of T-cell mediated DHR in certain populations (Table 1).12 This review focuses on the purely T-cell mediated drug hypersensitivity reactions, although the same principles and models likely apply to B-cell mediated reactions as well.12–14 Here, we provide an overview of the data supporting current models of T-cell mediated DHR, propose a new model of drug hypersensitivity that expands upon the existing models to include the role of microbial pathogen exposure in the generation of drug-specific T-cell responses, and discuss the implications for clinical practice and drug safety, design and development..

Figure 1. Overview of adverse drug reactions.

Adverse drug reactions may result from either on-target or off-target interactions between the drug and cellular components. Variation in the cellular processes that modulate drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), drug transporters, and target receptor expression contribute to ADRs that are primarily mediated by pharmacologic mechanisms (pink oval). Off-target adverse effects may occur by both non-immune mediated and immune-mediated mechanisms (green oval). The immune-mediated ADRs include both antibody or non-antibody mediated (Type I-III) and T-cell mediated reactions (Type IV reactions).

Table 1.

HLA-associated drug hypersensitivity reactions

| Drug | IM-ADR | Associated HLA alleles | PPV | NPV | NNT | Populations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abacavir | Hypersensitvity syndrome | B*57:0149, 50, 54, 55 | 55% | 100% | 13 | European, African |

| Carbamazepine | SJS/TEN | B*15:0262, 63, 65–68, 78, 83, 148–150 | 3% | 100% in Han Chinese | 1,000 | Han Chinese, Thai, Malaysian, Indian |

| B*15:1172,73 | Korean, Japanese | |||||

| B*15:18, B*59:01 and C*07:04151 | Japanese | |||||

| A*31:0172, 74, 76, 77 | Japanese, northern European, Korean | |||||

| DRESS | 8.1 AH (HLA A*01:01, Cw*07:01, B*08:01, DRB1*03:01, DQA1*05:01, DQB1*02:01)152 | Caucasians | ||||

| A*31:0180 | 0.89% | 99.98% | 3,334 | Europeans | ||

| A*31:0180 | 0.59% | 99.97% | 5,000 | Chinese | ||

| A*31:0172, 74, 76, 77 | Northern Europeans, Japanese, and Korean | |||||

| A*11 and B*51 (weak)76 | Japanese | |||||

| MPE | A*31:0178 | 34.9% | 96.7% | 91 | ||

| Allopurinol | SJS/TEN, DRESS | B*58:01 (or B*58 haplotype)90, 93, 95, 153–156 | 3% | 100% in Han Chinese | 250 | Han Chinese, Thai, European, Italian, Korean |

| Oxcarbazepine | SJS/TEN | B*15:02 and B*15:1884,157 | Han Chinese, Taiwanese | |||

| Lamotrigine | SJS/TEN | B*15:02 (positive)84 | Han Chinese | |||

| B*15:02 (no association)158,159 | Han Chinese | |||||

| Phenytoin | SJS/TEN | B*15:02(weak), Cw*08:01 and DRB1*16:0266,82–84 CYP2C9*382 | Han Chinese | |||

| DRESS/MPE | B*13:01(weak), B*5101 (weak)82 CYP2C9*382 | Han Chinese | ||||

| Nevirapine | SJS/TEN | C*04:01160 | Malawian | |||

| DRESS | DRB1*01:01 and DRB1*01:02 (hepatitis and low CD4+)89,161 | 18% | 96% | Australian, European and South African | ||

| Cw*8 or Cw*8-B*14 haplotype162,163 | Italian and Japanese | |||||

| Cw*489, 164 | Blacks, Asians, Whites Han Chinese | |||||

| B*3589, B*35:01165 B*35:05166 | 16% | 97% | Asian | |||

| Delayed rash | DRB1*01167 | French | ||||

| Cw*0489, 168 | African, Asian, European, and Thai | |||||

| B*35:05, rs1576*G CCHCR1 status166,169 | Thai | |||||

| Dapsone | HSS | B*13:01170 | 7.8% | 99.8% | 84 | |

| Efavirenz | Delayed rash | DRB1*01167 | French | |||

| Sulfamethoxazol E | SJS/TEN | B*38154 | European | |||

| Amoxicillin- clavulanate | DILI | DRB1*15:01, DRB107 (protective), A*02:01, DQB1*06:02 and rs3135388, a tag SNP of DRB1*15:01- DQB1*06:02171–173 | European | |||

| Lumiracoxib | DILI | DRB1*15:01-DQB1*06:02-DRB5*01:01-DQA1*01:02 haplotype174 | International, multicenter | |||

| Ximelagatran | DILI | DRB1*07 and DQA1*02175 | Swedish | |||

| Diclofenac | DILI | HLA-B11, C-24T, UGT2B7*2, IL-4 C-590- A176–178 | European | |||

| Flucloxacilin | DILI | B*57:01, DRB1*01:07-DQB1*01:03177,179 | 0.12% | 99.99% | 13,819 | European |

| Lapatinib | DILI | DRB1*07:01-DQA2*02:01-DQA1*02:01180 | International, multicenter |

IM-ADR: (immune mediated adverse drug reaction); PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; NNT: number needed to test to prevent one case of IM-ADR; SJS/TEN: Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis; DRESS: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; MPE: maculopapular eruption; HSS: hypersensitivity syndrome; DILI: drug induced liver injury

Overview of the T-cell immune response, the αβ T-cell receptor, and MHC

During maturation in the thymus, developing T cells undergo the sequential processes of positive and negative selection to generate a functional repertoire that is composed of an individual-specific, HLA-restricted subset of the total possible repertoire encoded by the TCR genes. Engagement of the TCR by the appropriate peptide-MHC ligand results in T cell clonal proliferation and differentiation into effector and memory phenotypes (Figure 2a). A subset of the memory population, termed effector memory T cells (TEM), is characterized by the expression of the cellular marker CD45RO and lack of expression of the lymph node homing receptor CCR7.15 This allows these cells to maintain surveillance in the tissue site of the initial antigen encounter, which is often the site of pathogen re-exposure. Because these cells require fewer costimulatory signals for activation and retain the ability to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-2, IFN-γ) and cytotoxic peptides, they are equipped and poised at strategic anatomic sites to initiate a swift immune response at re-encounter with pathogen-specific antigens.15–22 Contact with peptide-MHC is mediated by the αβ T cell receptor (TCR), which is composed of two polypeptide chains that each contain a variable region (Vα and Vβ). The distal residues of these variable sequences comprise six complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that engage peptide-MHC on the surface of the target cell. The CDR1 and CDR2 loops mediate contact with the MHC binding groove α-helices while the CDR3 loops mediate the majority of peptide contacts and thus display the greatest degree of sequence variability in the TCR gene23. The majority of MHC sequence diversity is found among amino acids in the binding groove that mediate peptide binding to the MHC. This polymorphism is presumably the legacy of selection pressure to confer immunity against a myriad of infectious pathogens.24,25 Individuals who are heterozygous at the HLA loci will express a more diverse array of MHC proteins thereby increasing the diversity of peptides presented to T cells. Theoretically, this will increase the probability that a pathogen will be recognized and elicit an immune response.26–30

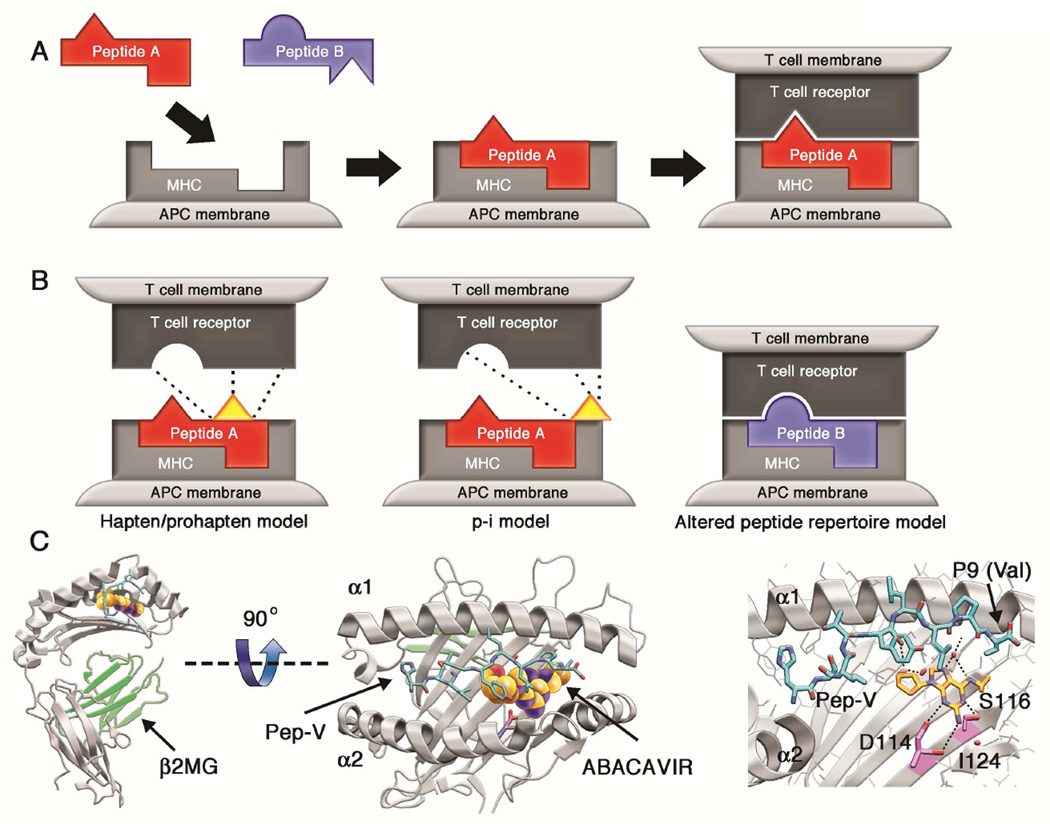

Figure 2. Models of T cell activation by small molecule antigens.

A: Peptide selection and presentation by MHC. Peptide antigens are bound to the MHC protein in the intracellular environment and expressed on the surface of the antigen presenting cell. In the example shown, peptide A is able to bind MHC but peptide B is not; thus peptide B is excluded from the repertoire of ligands presented in the context of this HLA allotype.

B: Mechanisms of T-cell activation by small molecules. Three models have been proposed to explain T-cell stimulation by small molecule pharmaceuticals. The hapten/prohapten model postulates that the drug binds to a protein that then undergoes antigen processing to generate haptenated peptides that are presented by MHC. The haptenated-peptide is recognized as a neo-antigen to stimulate a T-cell response (e.g., penicillin binding to serum albumin). The p-i model proposes that a small molecule may bind to HLA or T-cell receptor in a non-covalent manner to directly stimulate T-cells. The interaction of allopurinol with HLA-B*58:01 and carbamazepine with HLA-B*15:02 might adhere to the p-i model. The altered peptide model postulates that a small molecule can bind non-covalently to the MHC binding cleft to alter the specificity of peptide binding. This results in the presentation of novel peptide ligands that are postulated to elicit an immune response.

C: The abacavir-HLA-B*57:01 interaction demonstrates the altered peptide repertoire model. Shown is the crystal structure of the HLA-B*57:01 (gray) oriented with the peptide binding groove facing up in panel C1 and as viewed from above (birds-eye view of the peptide binding groove) in panel C2. Abacavir is represented as colored spheres, orange for carbon, blue for nitrogen and red for oxygen. The peptide HSITYLLPV is shown in cyan. Hydrogen bond interactions between abacavir and HLA-B*57:01 and peptide are shown as black dashes. The amino acids that differ between HLA-B*57:01 and HLA-B*57:03, which does not participate in abacavir-associated hypersensitivity, are highlighted in magenta.45 A video demonstrating the interactions of abacavir and the HLA-B*57:01 protein is available at the JACI website.

The immunopathogenesis of drug hypersensitivity: established models

The role of T-cell mediated immune responses in the pathogenesis of many IM-ADRs has been firmly established. The specific molecular mechanisms that underpin these reactions, however, have been elucidated in only a handful of cases. This is in contrast to the numerous reported associations among HLA alleles and drug-specific hypersensitivity reactions (reviewed in White et al.31 and Pavlos et al.12). Three non-mutually exclusive models that describe how a small molecule pharmaceutical might elicit T-cell reactivity have been developed, namely the hapten/prohapten model, the pharmacological interaction (p-i) model and the altered peptide repertoire model (Figure 2b).

In the hapten/prohapten model, the offending drug or a reactive metabolite of the drug binds covalently to an endogenous protein that then undergoes intracellular processing to generate a pool of chemically-modified peptides. When presented in the context of MHC, these modified peptides will be recognized as “foreign” by T cells and elicit an immune response which may also include a B-cell mediated antibody response.32–35 Examples of IM-ADR that are associated with hapten modification of endogenous proteins include the binding of penicillin derivatives to serum albumin and protein modification by the nitroso-sulfamethoxazole metabolite of sulfamethoxazole.35,36

Under the p-i model, the offending drug is postulated to bind non-covalently to either the TCR or MHC protein in a peptide-independent manner to directly activate T cells.37 Experiments demonstrating that some drugs are able to trigger T-cell responses in the absence of intracellular peptide processing, such as following the fixation of APCs, support this hypothesis.38–41 This model has also been hypothesized to explain in vitro T-cell reactivity that has been observed within seconds of drug exposure, a time course that is inconsistent with intracellular antigen processing, or for IM-ADR that are observed following first encounter with a drug.33,37

When IM-ADR adheres to the altered peptide repertoire model, the offending drug occupies a position in the peptide binding groove of the MHC protein thereby changing the chemistry of the binding cleft and the peptide specificity of MHC binding. It is proposed that peptides presented in this context are recognized as “foreign” by the immune system and therefore elicit a T-cell response.42–44 Examples of well described T-cell mediated drug hypersensitivity reactions are discussed below.

Drug-specific models: abacavir

Data to support the altered peptide repertoire model of IM-ADR has stemmed from careful characterization of the hypersensitivity reaction associated with the antiretroviral drug abacavir.44–46 Abacavir is a guanosine analog that inhibits the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase enzyme and is used as part of combination therapy for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. In early studies, hypersensitivity type reactions were reported in approximately 5–8% of patients within the first 6 weeks following initiation of abacavir. These reactions were named the abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome and were characterized by fever, malaise, gastrointestinal, and/or respiratory symptoms.47,48 In 2002, a strong association between carriage of the HLA class I allele HLA-B*57:01 and abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome was reported.49,50 Key clinical studies that confirmed the immunologic basis of this syndrome included the use of epicutaneous patch testing to demonstrate responses to abacavir in HLA-B*57:01 positive patients with history of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome.51–55 These observations were followed by the PREDICT- 1 and SHAPE trials which showed that screening for and exclusion of HLA-B*57:01 carriers from abacavir drug exposure could eliminate the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome with a 100% negative predictive value and a 55% positive predictive value.54,55 The PREDICT-1 study also showed that clinical onset of patch test confirmed abacavir hypsersensitivity cases occurred in as little as 1.5 days and up to three weeks following initiation of therapy (median 8 days)56. Ex vivo studies have shown that CD8+ T cells derived from abacavir hypersensitive patients are activated following exposure to abacavir-stimulated HLA-B*57:01 expressing APCs.57,58 Additionally, T cells isolated from abacavir-naïve, HLA-B*57:01 positive individuals have been shown to proliferate and become activated in response to abacavir exposure in 14-day cell culture systems.59,60 Studies indicate that these reactive CD8+ T cells have been shown to originate from both memory and naïve T cell populations and do not require costimulatory signals or CD4+ T cell help.56,60 Additionally, Adam et al. demonstrated that a subset of abacavir-reactive T cell clones derived from HLA-B*57:01 positive, abacavir-naïve subjects cross-react with endogenous peptide presented in the context of HLA-B*58:01.60 This data provides evidence that an abacavir-induced neo-epitope can stimulate cross-reactive T cells in vitro. However, it remains unclear how these findings might account for the pathogenesis of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome in vivo.. No cases of abacavir hypsersensitivity syndrome have been associated with HLA-B*58:01 carriage and therefore it appears as though this allo-allele is not present in case patients.

Visualization of the molecular composition of the altered peptide repertoire model was provided in two simultaneous reports of the crystal structure of HLA-B*57:01 in complex with abacavir and peptide.45,46 These studies demonstrate metabolism-independent, direct, non-covalent, and dose dependent association of abacavir with amino acids in the HLA-B*57:01 binding cleft. Furthermore, approximately 20–45% of the peptides eluted from abacavir-treated HLA-B*57:01 APCs were distinct from those recovered from untreated cells, illustrating a dramatic shift in the repertoire of HLA-B*57:01 bound peptide in the presence of abacavir.44–46

Drug-specific models: the aromatic amine anticonvulsants

Carbamazepine is an aromatic amine anticonvulsant used for the treatment of epilepsy, bipolar disorder, and trigeminal neuralgia. The spectrum of IM-ADR that have been reported following carbamazepine administration is varied and includes SJS/TEN, maculopapular exanthema, and DRESS.61 In a 2004 study, it was demonstrated that carriage of the HLA-B*15:02 allele was associated with carbamazepine-induced SJS/TEN in Han Chinese patients (100% carriage in carbamazepine-SJS/TEN patients vs. 3% carriage in carbamazepine tolerant controls; negative predictive value approaches 100%).62 This association was later confirmed in persons of Thai, Malaysian, and Indian ethnicities.63–69 Subsequent studies identified a dominant TCR clonotype, Vβ-11-ISGSY from 84% of patients with carbamazepine-associated SJS/TEN. This TCR was found in only 14% of carbamazepine-naïve healthy controls and absent in carbamazepine-tolerant patients.70 Additionally, T cells derived from carbamazepine-naïve, HLA-B*15:02 and TCR Vβ-11-ISGSY positive patients acquired a cytotoxic phenotype following carbamazepine exposure in cell culture experiments that was blocked by the addition of Vβ-11-ISGSY specific antibody.70 More recent experiments involving next generation sequencing of T cells obtained from the blister fluid of eight Taiwanese patients with HLA-B*15:02 associated carbamazepine-SJS/TEN demonstrated a predominance of a T-cell clonotype bearing a separate specific TCR (Hung and Chung, unpublished data). These studies are the first to identify the concomitant involvement of both a specific HLA allotype and TCR clonotype in the pathogenesis of an IM-ADR. The structural basis for this association, however, has not been fully characterized.

Carbamazepine presentation in the context of HLA-B*15:02 has been shown to be independent of intracellular drug or antigen processing but does require MHC-peptide binding in order to stabilize the peptide-MHC complex on the cell surface. In vitro studies have demonstrated carbamazepine binding to other members of the HLA class I B75 serotype family, suggesting that residues conserved among B75 alleles are involved in the HLA-carbamazepine interactions.71 Consistent with this hypothesis, mutagenesis and modeling studies have shown that the carbamazepine binding site on HLA-B*15:02 maps to the vicinity of the B pocket of the MHC peptide binding cleft, specifically residues Asn63, Ile95, Leu156 and likely Arg62, of which many are shared by members of the HLA-B75 family.71 Although the observation that neither drug nor antigen processing is required for T-cell activation might support the p-i concept., However, a separate study found that approximately 15% of peptides eluted from carbamazepine-treated APCs expressing HLA-B*15:02 were distinct from those bound to HLA-B*15:02 in the absence of carbamazepine exposure consistent with the altered peptide repertoire model of drug-HLA association.46

It is important to note that not all patients with carbamazepine-associated SJS/TEN carry the HLA-B*15:02 allele. In Indian, Japanese, and Korean cohorts, carbamazepine-SJS/TEN has been observed in association with carriage of other HLA alleles in the B75 serotype family including HLA-B*15:21, HLA-B*15:11, and HLA-B*15:08.64,72,73 Carbamazepine-DRESS/DIHS is not associated with HLA-B*15:02. In addition, separate analyses have demonstrated an association between carbamazepine induced IM-ADR and carriage of the HLA-A*31:01 allele in Han Chinese (with DRESS but not SJS/TEN), Northern European, Japanese, and Korean populations.74–78 This association, however, was not consistently seen in subsequent studies many of which also reported a range of phenotypic variation among the carbamazepine induced IM-ADR observed.77,79–81 Work to more precisely define these associations and the structural basis for these interactions is ongoing.

Phenytoin, also an aromatic amine anticonvulsant, has been associated with severe cutaneous adverse reactions including SJS/TEN, DRESS, and maculopapular eruption. A recent GWAS followed by direct sequencing of candidate genes involving 105 cases of phenytoin-associated severe cutaneous reactions (including 61 patients with SJS/TEN, 44 patients with DRESS, and 78 patients with maculopapular eruption), 130 phenytoin-tolerant controls, and 3655 population controls from Taiwan, Malaysia, and Japan revealed a strong signal at loci in chromosome 10 (CYP2C) but not chromosome 6 (MHC). Further analysis demonstrated that phenytoin induced severe cutaneous reactions are strongly associated with carriage of the CYP2C9*3 allele (overall OR 11, 95% CI, 6.2–18; p<0.00001; OR for SJS/TEN in subgroup analysis = 30).82 Phenytoin is metabolized to an inactive metabolite by the CYP2C9 enzyme and variation in this gene was associated with a 93–95% reduction in drug clearance in the study population. Additionally, delayed phenytoin clearance was observed in patients with phenytoin-ADR in the absence of CYP2C9 variants suggesting that other factors contribute to phenytoin accumulation. For example, renal or hepatic insufficiency or drug-drug interactions that inhibit cytochrome p450, likely predispose to phenytoin-ADR and these adverse reactions are, at least in part, dose dependent. This study also demonstrated a weak association between phenytoin-ADR and carriage of HLA-B*13:01, HLA-B*15:02, and HLA-B*51:01. In a subgroup analysis, the OR for HLA-B*15:02 carriage as a predictor of phenytoin-SJS/TEN was found to be 5.0 (p=0.25) and this association has been observed in prior studies.66,82–84 Combined screening for CYP2C9 variants and HLA-B*15:02 carriage improved the sensitivity for phenytoin-SJS/TEN to 62.5% but decreased the specificity (to 86.2% from 97.7% for CYP2C9 variant alone) of the screening strategy.82 These findings add to a growing number of observations showing that multiple processes including pharmacological and immunological mechanisms contribute to ADRs that may be mediated by the parent drug, and that dose dependency is likely a key feature of both on-target and off-target ADRs (Figure 1).85–89

Drug-specific models: allopurinol

Allopurinol is a xanthine oxidase inhibitor that is used to treat hyperuricemia and is associated with an IM-ADR of variable, but primarily cutaneous, phenotype in approximately 2% of patients who initiate therapy. In 2005, it was demonstrated that the HLA-B*58:01 genotype is associated with allopurinol-induced SJS/TEN and DRESS in persons of Han Chinese ancestry (100% negative predictive value, 3% positive predictive value).90 This association has since been identified in Thai, Korean, and Japanese populations and it is estimated that HLA-B*58:01 explains approximately 60% of allopurinol inducted IM-ADRs in European and Japanese populations.91–95

Unlike abacavir or carbamazepine, both of which drive T-cell reactivity in the absence of drug modification, both allopurinol and its metabolite oxypurinol have been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of allopurinol associated IM-ADR. In vitro studies have demonstrated that T cells isolated from both allopurinol-naïve, HLA-B*58:01-positive individuals and from patients with history of allopurinol induced IM-ADR rapidly proliferate and become activated following exposure to allopurinol or oxypurinol.96,97 This response occurs within seconds of drug exposure, is not dependent upon antigen processing or antigen presentation by APCs, and is abrogated if cells are washed to remove free drug. Taken together, this suggests that the drug-peptide-MHC interaction is non-covalent in nature and occurs after peptide-loaded MHC are expressed on the surface of the APC. While the majority of oxypurinol-induced T-cell reactivity was shown to be HLA-B*58:01 restricted, allopurinol-associated T-cell responses occurred in the context of multiple class I HLA alleles. Further, this study also demonstrated polyclonal T -cell reactivity to both allopurinol and oxypurinol.97 These findings might be explained by a modified version of the p-i hypothesis in which endogenous peptide bound to cell surface MHC intermittently and incompletely dissociates from the peptide binding groove to permit allopurinol or oxypurinol to occupy a site in the binding cleft. This then alters the conformation of the bound peptide to create an antigen that is recognized by T cells to trigger an immune response.97,98

The low positive predictive value of HLA-B*58:01 carriage as a predictor of allopurinol associated IM-ADRs suggests that other factors likely contribute to pathogenesis.97 Indeed, it is now known that elevated serum oxypurinol concentration is an important risk factor for allopurinol IM-ADR.99 The half-life of orally administered allopurinol is only 1–2 hours while the half-life of oxypurinol is 15 hours in the setting of normal renal function, longer in the setting of renal insufficiency. Importantly, both impaired renal function and increased plasma concentrations of oxypurinol and granulysin, a known mediator of tissue injury in SJS/TEN, have been shown to correlate with disease severity and mortality in allopurinol-SJS/TEN/DRESS, demonstrating the dose-dependency of these responses. 99,100

T cell plasticity and expanded models of IM-ADR pathogenesis

Protective cellular immunity requires that our T cell repertoire responds to an extraordinarily large number of potential antigens.101–103 One way in which our immune system has evolved to contend with this degree of antigenic diversity is through the generation of polyspecific TCRs that are capable of recognizing multiple peptides. Thus, a single TCR might recognize peptides derived from more than one pathogen, thereby enhancing our ability to defend against the wide microbial universe. This concept is termed heterologous immunity and there exist numerous examples of clinical and experimental observations to support this paradigm.101,104

The concept of heterologous immunity is similar to but distinct from that of direct alloreactivity—a setting in which a cross-reactive TCR recognizes peptide antigen presented in the context of non-self MHC. This phenomenon is the basis of acute tissue rejection following solid organ transplantation and for graft-versus-host disease following hematopoetic stem cell transplantation. Alloreactivity is a common phenomenon and multiple studies have demonstrated that alloreactive memory T cell responses pose a significant barrier to tissue transplantation. These memory responses are, at least in part, derived from heterologous virus-specific memory T cells.23,105,106,104,107 Of the viral pathogens that have been shown to be associated with T-cell alloreactivity, members of the human herpesvirus (HHV) family have been most frequently observed and best characterized.108 This is not surprising given that heterologous immune responses stem from pre-existing memory T cells and that HHV-specific T cells, such as those directed against Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV), make up a significant proportion of the memory pool.109–113

Multiple models have been experimentally validated to describe the molecular events that form the foundation of cross-reactive T-cell responses. First, a single memory T cell might be expected to recognize peptide-MHC complexes that are structurally similar to the primary peptide-MHC immunogen and in which the molecular contacts are preserved. Interactions such as this are considered examples of molecular mimicry and it has been shown that neither HLA-restriction nor peptide sequence homology are prerequisite for the development of heterologous responses. For instance, the human TCR LC13 recognizes the EBV immunodominant epitope FLRGRAYGL bound to HLA-B*08:01 but has also been shown to recognize endogenous peptides presented in the context of HLA-B*44:02 and HLA-B*44:05. Crystal structures of each LC13-peptide-MHC complex revealed that the molecular contacts are nearly identical among these pairs despite significant sequence diversity among the HLA proteins and the peptides themselves.114 Thus, conservation of the structural and chemical properties of the contact residues at the TCR-peptide-MHC interface is key to cross-reactivity by the molecular mimicry model.115

Another mechanism that might promote TCR cross reactivity involves the structural flexibility of the TCR protein itself. As discussed previously, the regions of the TCR that mediate contact with peptide-MHC, the α- and β-chain CDRs 1–3, rest atop flexible arms in the folded protein. Because of this, the TCR can alter peptide-MHC interactions by shifting the orientation of the CDRs through an “induced fit” mechanism.23 For example, the murine BM3.3 TCR was shown to recognize two antigenically distinct peptides through large conformational shifts in the orientation of the CDR3α loop.116,117 The two peptides used in these studies shared no sequence homology but both were presented in the context of the mouse HLA homolog H-2Kb. Similarly, large conformational shifts in the orientation of the CDRs have been demonstrated in structural comparisons of free versus bound TCRs in multiple studies (reviewed in Rudolph et al.23). Further, it has also been shown that some cross-reactive TCRs recognize multiple peptide-MHC complexes through entirely distinct binding orientations with little-to-no overlap among contact residues at the TCR-peptide-MHC interface.118 Thus, alterations in the protein-protein interactions—either through modulation of flexible domains of the TCR or through the use of an alternate binding strategy—can afford a single TCR the ability to engage multiple ligands.

Unexplained features of T-cell mediated ADRs

While the existing models that describe drug-peptide-MHC interactions illuminate key features of T-cell associated ADR pathogenesis, many important observations related to these reactions remain unexplained. Such as, what might account for the differences among the clinical phenotypes of individual ADRs? Abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome is characterized predominantly by fever, gastrointestinal, and respiratory symptoms and is less commonly associated with rash. In contrast, the T-cell mediated hypersensitivity reactions associated with carbamazepine exposure are most commonly severe cutaneous and systemic reactions such as SJS/TEN and DRESS. Carbamazepine has also been shown to cause the full spectrum of IM-ADR and specific phenotypes have been associated with carriage of specific HLA alleles (Table 1). There also exists wide variability in the timing of clinical onset of many IM-ADRs. For example, immunologically-mediated abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome has been demonstrated to occur within as little as 1.5 days from first exposure to up to three weeks following initiation of therapy.54 Similarly, onset of carbamazepine-associated IM-ADR has been observed to occur over a broad timeframe with onset of symptoms generally occurring later, after 2–8 weeks of drug therapy.61 Another unexplained outcome, as demonstrated in Table 1, is that many of the T-cell mediated ADRs are characterized by a high negative predictive value for HLA association but, paradoxically, the positive predictive values for these associations are much lower. For instance, why is it that 55% of HLA-B*57:01 carriers will develop a hypersensitivity reaction in response to abacavir exposure but only 3% of HLA-B*15:02 carriers exposed to carbamazepine will develop SJS/TEN? What are the differences among those individuals who develop abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome and carbamazepine-SJS/TEN and those who do not? It is notable that, in vitro, abacavir-specific CD8+ T-cell responses can be elicited from 100% of HLA-B*57:01-positive abacavir-naive healthy blood donors but in vivo CD8+ T-cell responses, demonstrated by skin patch testing, occur only in HLA-B*57:01 positive patients with prior abacavir exposure and history of a hypersensitivity reaction. 59,119 What mechanisms might account for these discrepant observations? Finally, in some cases, immunologically-mediated drug-specific recall reactions have been demonstrated years after drug exposure and withdrawal. For example, it has been shown that abacavir-specific in vivo (skin patch test) and ex vivo (ELISpot) responses remain positive years after clinical abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome in the absence of subsequent re-exposure to abacavir.56,57,119 Similarly, long-lived T-cell responses have been observed in patients with history of carbamazepine-SJS/TEN years after clinical reaction.120–122 What antigen is maintaining these memory T-cell responses?

Incorporating heterologous immunity into the models of IM-ADR

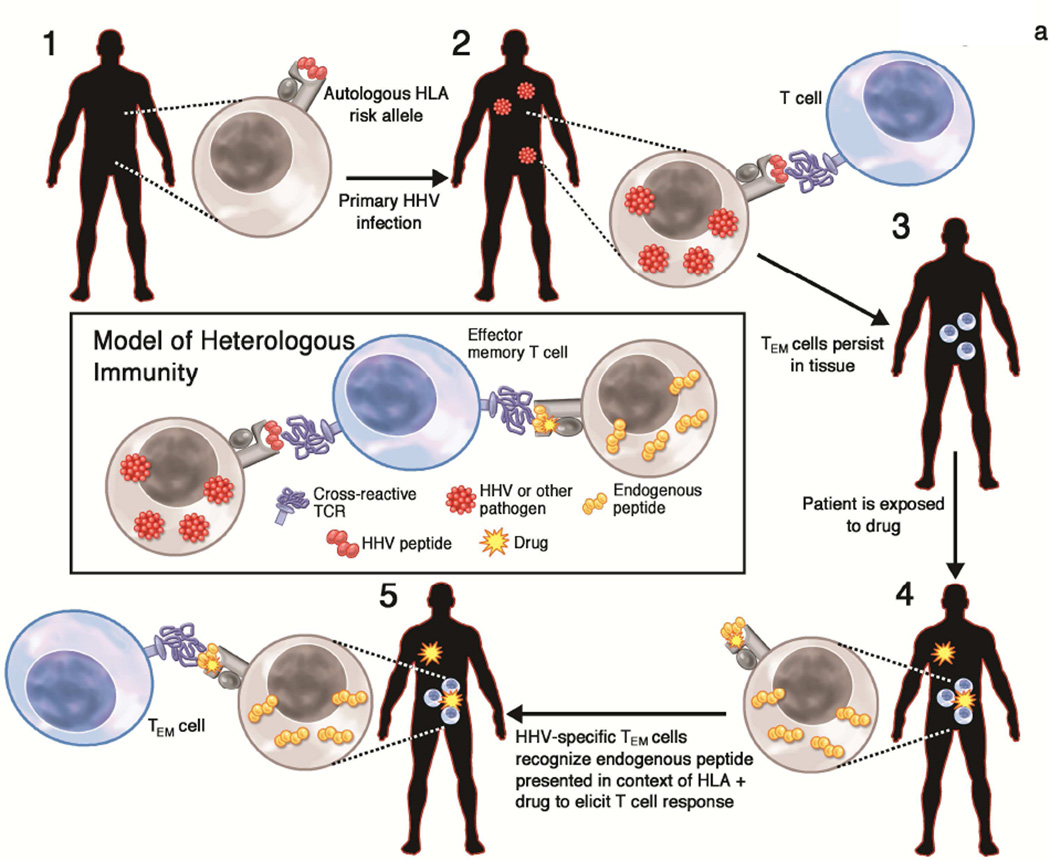

We propose that some T-cell mediated hypersensitivity reactions likely represent yet another example of heterologous immunity. According to this model, a substantial proportion of the cross-reactive T-cell responses likely stem from activation of pathogen-specific effector memory T cells, sensitized much earlier, that subsequently recognize the neo-antigen created by drug exposure (Figure 3a).

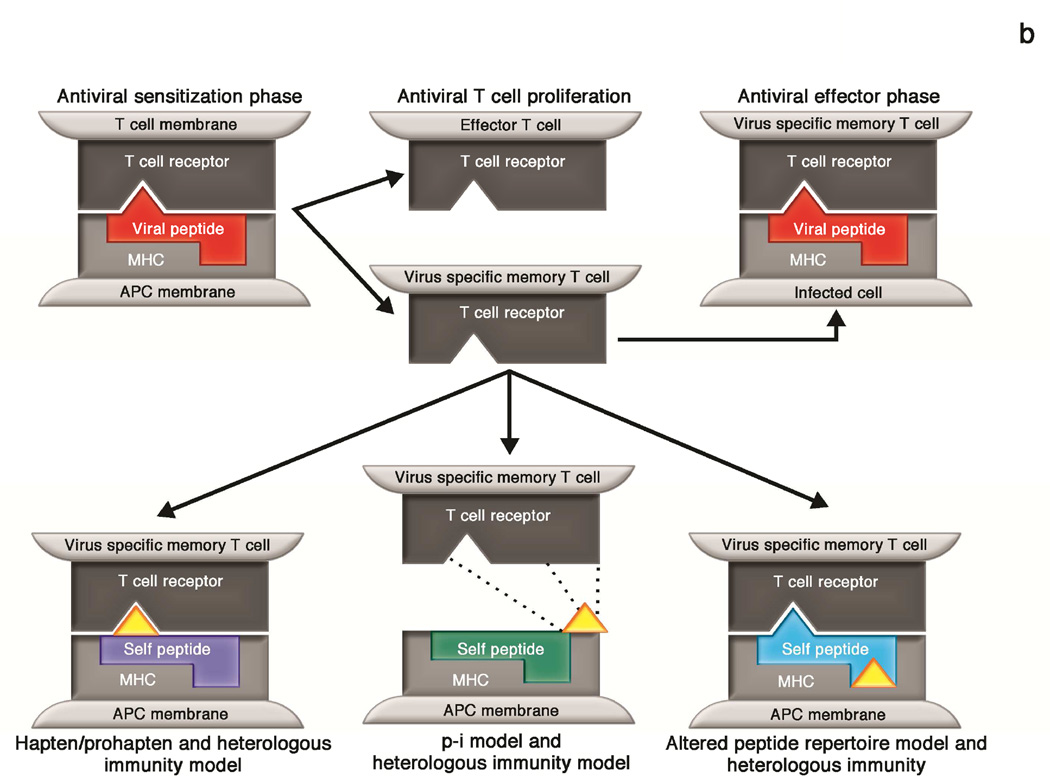

Figure 3. Generation of heterologous immune responses that contribute to the pathogenesis of T-cell mediated ADRs.

A: Timeline of the generation of IM-ADR. According to the heterologous immunity model, the generation of an IM-ADR requires the presence of the HLA risk allele, infection by HHV (or other pathogen), and the generation of a pathogen-specific memory T cell response that is cross-reactive with drug-induced peptide epitopes presented much later.

B: Integration of the models of T-cell activation by small molecules and heterologous immunity. In the heterologous immunity model, memory T cells are generated following pathogen exposure and reside at specific anatomic sites. These memory T cells may cross react with 1) haptenated endogenous peptides presented in the context of the HLA risk allele, 2) drugs that bind the TCR and/or MHC in a non-covalent manner under the p-i model, or 3) an altered repertoire of endogenous peptides following drug binding to MHC.

Of the microbial pathogens that might prime such heterologous immune responses, the human herpesviruses (HHV) standout as likely sources of persistent antigen for the generation of long-lasting cross-reactive T cells. The HHV are ubiquitous pathogens that are notable for their ability to establish lifelong infection and cellular latency. Periodically, the latent HHV will turn on transcriptional programs that result in presentation of viral proteins that stimulate the local population of virus- specific memory T cells. Activation of these T-cell responses results in rapid containment of viral replication and forces the virus to return to a quiescent state. A consequence of this intermittent stimulation is the expansion of virus-specific memory T cells without the development of T-cell exhaustion.123 Multiple studies have demonstrated that CMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells account for a major proportion of the total memory T cell repertoire in CMV-seropositive adults and that this proportion increases with aging (estimated to be 10–40% of total CD4+ repertoire and up to 10% of total CD8+ repertoire).109–112 Recently, longitudinal studies involving human subjects with history of genital HSV infection have demonstrated that HSV-specific CD8+ T cells are retained in the genital mucosa following infection as tissue resident memory T cells long after active infection is contained. These cells are mostly CD3+ and, in humans, are likely to express CD8αα and CD69, and secrete cytotoxic molecules such as perforin and granzyme.18,124

According to the heterologous immunity model (Figure 3a), the pathogenesis of a T-cell mediated ADR, considered over the course of an affected individual’s lifetime, can be summarized as follows: 1) A prerequisite feature of each T-cell mediated ADR is carriage of the HLA risk allele; this is necessary but not sufficient for the reaction. 2) The subject acquires primary infection by HHV (or other pathogen). HHV peptides are presented in the context of the HLA risk allele and a polyclonal CD8+ T cell response contains the virus. The HHV establishes latency and the T cell response contracts. 3) Memory T cells persist at the site of antigen encounter. This cell population is intermittently stimulated by viral antigens during viral reactivation. Activation of TEM cells forces the virus back into latency. 4) Later in life, the subject is exposed to the offending drug. The drug interacts with the pathogenic HLA protein through one or more mechanisms as described in the text. This results in either neoantigen formation (as might be seen with haptenated peptide), direct activation of T cells, or presentation of an altered repertoire of endogenous peptides. 5) The peptide-MHC complex is recognized by the TCR that was initially primed against HHV peptide either through molecular mimicry or via an alternate binding strategy. This triggers activation of the memory T cells and results in clinical ADR.

It is important to note that this model includes two points of HLA restriction—at the initial encounter with pathogen antigen to generate the primary T-cell response and then again at the time of endogenous peptide presentation in the setting of drug exposure. The requirement for antigen presentation in the context of the same HLA risk allele at two distinct steps in this process likely explains the specific HLA restriction that has been observed with clinical IM-ADR such as abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome and carbamazepine-SJS/TEN. It should also be recognized that the heterologous immunity model does not supplant the existing models that describe drug-peptide-MHC interactions (hapten/prohapten, p-i, and altered peptide repertoire models). Instead, we argue that heterologous immunity likely contributes to IM-ADR that occur via any (or more than one) of these models, as depicted in Figure 3b.

Viral replication is not required for IM-ADR under the heterologous immunity model

The heterologous immunity model is not dependent upon the presence of active pathogen replication at the onset of the adverse drug reaction. Under this model and as described above, the memory T-cell responses that are driving the IM-ADR are derived from much earlier stimulation by pathogen peptides during active infection and/or reactivation, are cross-reactive, and are stimulated by endogenous peptide epitopes presented in the context of the drug. At the initiation of IM-ADR, endogenous peptide-drug epitope drives the T-cell response, not pathogen replication, which needs to be distinguished from HHV (HHV-6/7, EBV, CMV) reactivation that can occur in the setting of DRESS.125–130 Key to these observations is that HHV replication, as detected by viral DNA PCR, has not been observed early in clinical course of DRESS and generally, viremia is observed greater than two weeks following symptom onset suggesting that viral reactivation itself does not mediate the onset of DRESS.126–129 It is therefore possible that this late viral reactivation is the result of general immune dysregulation. Expansion of virus specific regulatory T cells have been identified late in the course of DRESS and long-term loss of suppressive function of regulatory T cells upon clinical resolution of DRESS has been described.131,132 HHV reactivation occurs almost exclusively in relation to DRESS and is not seen in SJS/TEN in the absence of severe immunosuppression. Reactivation may be subclinical or may manifest as recurrence of one more DRESS symptoms (e.g. hepatitis or rash) in the absence of drug. Reactivation may also manifest as systemic or organ specific viral disease and a case report of recurrent CMV colitis on phenytoin rechallenge in a patient with history of phenytoin DRESS two years prior highlights this reproducibility of tissue specific viral disease.133 Autoimmunity can occur as both a subclinical and clinical late complication of DRESS and this may relate to reactivation of HHV-6 and potentially other HHV although the specific immunopathogenesis is currently uncertain.134,135

Explaining the unexplained: the consequences of heterologous immunity in IM-ADR pathogenesis

The heterologous immunity model addresses many of the outstanding questions surrounding the pathogenesis of IM-ADR. For instance, if we suppose that tissue resident memory T cells that were previously primed against a mucocutaneous HHV, such HSV-1, HSV-2, or VZV, were cross-reactive with peptides presented in the context of HLA-B*15:02 and carbamazepine, then this might explain why the carbamazepine-associated SJS/TEN phenotype is limited to the skin and mucosa. In contrast, the TEM clonotype that participates in abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome is likely derived following primary exposure to systemic HHV such as CMV, EBV, or HHV-6. This may explain why the abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome phenotype is one in which systemic symptoms and internal organ pathology is a dominant feature. In addition, tissue-specific expression of endogenous peptides might influence the phenotype restriction of certain ADRs, as has been suggested for tissue rejection following transplantation.136 For example, it is plausible that the skin and mucous membrane limited phenotype associated with HLA-B*15:02-restricted carbamazepine-SJS/TEN might result from T cell recognition of an endogenous peptide that is preferentially presented by keratinocytes and not by other cell types. It is important to note that the extent of tissue involvement in primary or reactivation HHV infection and in an ADR is a feature of the antigen distribution in each case. For example, in the case of VZV reactivation in an immunocompetent subject (shingles), it is common that lesions appear in a dermatomal distribution determined by the site of VZV reactivation. Here, the relevant antigen is present only in a limited tissue distribution and therefore only T cells in the local area are activated. However, in the setting of ADR the drug is distributed widely and the relevant drug-induced epitope is presented throughout the body in the context of the MHC class I risk allele. The cross-reactive T cell clonotype that was initially primed against VZV is now activated by the drug-peptide-MHC epitope and the ensuing immune response is no longer limited to the site of VZV reactivation—the relevant antigen is now widely distributed and the T cell response follows this distribution. This might result in an ADR with expansive tissue involvement such as SJS/TEN.

The heterologous immunity model might also account for the more rapid development of clinical symptoms observed with certain ADR phenotypes following initial drug exposure (e.g., SJS/TEN versus DRESS). As previously described, TEM cells require minimal co-stimulatory signals for activation and, when exposed to cognate peptide-MHC ligand, have the potential to rapidly proliferate and execute effector functions. This would occur on a timescale consistent with clinical onset and progression of many of the known HLA-associated ADRs. Further, the requirement for both a specific HLA-restriction and the use of a specific TCR clonotype that targets a specific pathogen epitope is one potential explanation for the very low positive predictive values observed for HLA carriage as a predictor of a particular ADR.70 Indeed, a patient’s prior history of pathogen exposure shapes which TCRs are present in the memory population. Thus, HLA-B*57:01 carriers who do not develop a hypersensitivity reaction in response to abacavir exposure might be predicted to have a different repertoire of TCRs that excludes the pathogenic clonotype involved in abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome and, possibly, a different history of HHV or other pathogen exposures as compared to abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome case patients. Finally, the heterologous immunity model might provide an explanation as to why some drug-specific T-cell responses are particularly durable. As mentioned previously, patients with a history of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome and those with history of carbamazepine-SJS/TEN have been shown to maintain robust epicutaneous patch test and ex vivo responses for years following therapy in the absence of continued drug exposure.56,57,120–122 Generally, we would expect these responses to wane with time unless there exists a persistent source of antigen from a chronic persistent pathogen such as HHV that maintains these specific T-cell populations.

Early data that may support the heterologous immunity model include the identification of abacavir-reactive, pre-existing memory CD8+ T cell responses in HLA-B*57:01-positive abacavir-naïve healthy donor subjects. These memory T cells respond to abacavir in vitro without the need for costimulatory signals or CD4+ T-cell help.56,60 Additionally, as mentioned previously, analysis of blister fluid from carbamazepine-SJS/TEN patients identified a highly frequent and specific TCR which showed similarity to the TCR clonotype of the T cells isolated from the genital mucosa of patients with HSV-2 infection (Hung and Chung, unpublished data).18 Work to define the cross-reactivity of these clonotypes is ongoing.

T cell plasticity and drug-induced alloreactivity

While the incorporation of heterologous immunity with the existing models of drug-peptide-MHC interaction provides a biologically plausible hypothesis to explain in vivo IM-ADR pathogenesis, it cannot account for all in vitro observations. As mentioned previously, recent studies have demonstrated that both memory and naïve CD8+ T cells obtained from HLA-B*57:01-positive, abacavir-unexposed individuals are activated following exposure to abacavir-treated cultured APCs, independent of costimulatory signals or CD4+ T cell help.56,60 About 40% of these cells reacted immediately to the newly formed abacavir-peptide-MHC complex and a proportion of the abacavir-induced T cells might also cross recognize peptide antigen presented in the context of HLA-B*58:01. These findings demonstrate that the abacavir-peptide-MHC complex is capable of inducing the formation of allo-reactive T cells in vitro and this highlights the plasticity of the drug-induced T-cell repertoire.60 However, these results conflict with certain features of clinical IM-ADR and should therefore be considered with caution as a model for in vivo adverse drug reactions. First, the in vitro finding that T cells from all HLA-B*57:01 donors, including those obtained from abacavir-naïve, abacavir-tolerant, and patients with history of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome, respond to abacavir-stimulated APCs in cell culture experiments is incompatible with patch test data showing that only patients with a history of abacavir hypersensitivity display in vivo T-cell responses to abacavir.51–55 Second, the observed reactivity of abacavir-induced CD8+ T cells against peptide presented in the context of HLA-B*58:01 is inconsistent with epidemiological data showing that clinical abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome occurs exclusively in the setting of HLA-B*57:01 carriage. Therefore, the hypothesis that an allo-allele response is mechanistic in vivo is incompatible with current clinical data which shows that the allo-allele is not present in clinical abacavir hypersensitivity cases. Finally, the in vitro observation that abacavir-induced T cells can react immediately to abacavir-stimulated APCs, and that this reactivity can also be induced in the absence of any APC, does not correspond to the timing of the clinical onset of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome or the requirement for HLA-restriction seen in clinical cases. Taken together, these findings offer interesting insight into the polyspecificity of drug-induced T-cells60,137 but it remains to be proven whether these mechanisms contribute to in vivo IM-ADR.

It should be emphasized that the models presented above, including heterologous immunity and the molecular models of drug-peptide-MHC interaction (hapten/prohapten, p-i, and altered peptide repertoire model) are not mutually exclusive nor is it requisite that they occur together for each IM-ADR. If the naïve T-cell repertoire does indeed contribute to clinical IM-ADR, then it is plausible that these reactions stem from de novo responses to the drug-peptide-MHC complex. This might help explain the variability of time-to-symptom onset for certain clinical syndromes such as abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome and carbamazepine- SJS/TEN. It is possible that pre-existing cross reactive memory CD8+ T cells are pathogenic in cases of early onset IM-ADR via the heterologous immunity model (i.e., abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome cases with clinical onset at 1.5 days) and that de novo activation of a naïve T cell might account for the cases of IM-ADR with somewhat delayed onset (i.e., abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome cases with clinical onset at three weeks). Future work to precisely identify the T-cell subsets that participate in clinical IM-ADR is needed to define the pathogenesis of adverse drug reactions.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Predicting risk for ADR in the clinical setting

The opportunity to identify patients who are at risk for an ADR via pharmacogenomics screening prior to drug administration is an attractive concept given the substantial cost, morbidity, and mortality associated with these reactions. Following the PREDICT-1 and SHAPE trials in 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black box warning against the use of abacavir in patients known to carry the HLA-B*57:01 allele. Since that time, the U.S. FDA, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the European Medicines Agency, the Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium and multiple international HIV/AIDS organizations have recommended HLA-B*57:01 genotyping in any patient for whom abacavir therapy is considered and exclusion of abacavir therapy for any patient with a positive test.138–142 Similarly, the U.S. FDA recommends screening for carriage of HLA-B*15:02 in persons of Asian ancestry prior to initiation of carbamazepine and avoidance of carbamazepine therapy in all HLA-B*15:02 carriers, regardless of ethnicity, unless the benefits of treatment clearly outweigh the risk of ADR.143,144 HLA-B*15:02 screening prior to carbamazepine prescription has been funded and implemented in Taiwan since 2010, and as a result along with restricted off-label use of carbamazepine, the incidence of carbamazepine-SJS/TEN has declined dramatically and allopurinol is now the most common cause of SJS/TEN in Taiwan as well as in many other Asian countries. More recently, the strong association of allopurinol-SJS/TEN/DRESS with the HLA-B*58:01 genotype has led the Taiwan Department of Health to recommend screening prior to initiation of therapy and a prospective study to evaluate the clinical utility of HLA-B*58:01 screening prior to allopurinol prescription in Taiwan is ongoing.145 Screening for HLA-B*58:01 prior to initiation of allopurinol has been endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology for those with advanced renal failure and/or from high risk populations such as Southeast Asian ancestry. A recommendation for HLA-B*58:01 screening has not been adopted by the U.S. FDA or other jurisdictions at this time. The less than 100% negative predictive value and low positive predictive value of HLA-B*58:01 for allopurinol ADRs in European, Japanese, and other non-Southeast Asian populations needs to be considered in the cost-effectiveness equation for HLA-B*58:01 screening.

These examples share key features that facilitate the translation of basic science discoveries into clinical practice. From a drug safety standpoint, the 100% negative predictive value for lack of reaction in the absence of allele carriage in the target population, the low number needed to test to prevent one case, and the paucity of safe, efficacious, and effective therapeutic alternatives are critical for incorporation of these screening strategies into clinical care. Additionally, the improved cost, turnaround times, and quality assurance associated with clinical laboratory diagnostic testing has allowed for feasible implementation of screening into clinical algorithms. In contrast, for many other drugs, such as flucloxacillin, a high utility anti-Staphylococcal penicillin used in the UK and Australia, pre-treatment screening appears to be neither cost-effective nor feasible; almost 14,000 patients would need to be screened to prevent one case of flucloxacillin-associated drug induced liver injury.

Given the low positive predictive values for the HLA-associated ADRs defined to date, screening strategies that focus solely on HLA genotyping will inevitably result in the denial of therapy to a large number of carriers of HLA risk alleles who would ultimately tolerate the drug in question without complication and benefit from its use. For example, the positive predictive value of HLA-B*58:01 carriage for allopurinol associated SJS/TEN/DRESS is only 3%. This low positive predictive value, however, must be weighed against the extreme short and long-term morbidity associated with SJS/TEN that is often not accurately captured in standard cost-effectiveness analyses. In the case of abacavir, carriage of the HLA-B*57:01 gene is associated with a much higher positive predictive value of 55% for abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome. Although true immunologically mediated abacavir hypersensitivity occurs in only 2–3% of patients who take abacavir, up to 12% of those treated will develop symptoms consistent with abacavir hypersensitivity that are secondary to a different pathogenic mechanism (e.g., viral infection or immune reconstitution following treatment of HIV infection). Prior to the routine use of HLA-B*57:01 screening, this led to the false diagnosis of abacavir hypersensitivity in these patients and withdrawal of abacavir—a treatment that is safe in this setting—thereby limiting the patient’s options for HIV therapy. To explain why a varying percentage of individuals carrying a specific risk allele will develop a given IM-ADR we therefore propose that, in addition to carriage of an HLA risk allele, other factors, such as heterologous immune responses stemming from cross-reactive T cells primed against viral pathogens, are required for the development of some ADRs. Further delineation of the T-cell specificities involved in these reactions will enhance our understanding of pathogenesis and potentially allow us to refine our screening protocols to more precisely identify those patients who are truly at risk for ADR. Advances in technologies to characterize the TCR repertoire within an individual patient, including deep sequencing techniques that target the TCR Vβ genes, ultrasensitive PCR assays to detect and quantify rare TCR variants, and, sequencing assays designed to identify paired TCR α- and β-chain sequences, will enable these discoveries. Further, new computational and experimental methods to identify the HLA-restricted HHV epitopes that prime the cross-reactive pathogenic TCRs in these reactions will shed light on the role of heterologous immunity as a mechanism of drug hypersensitivity.

Drug discovery: preclinical screening to improve drug safety

IM-ADRs are less common than adverse effects based solely on pharmacology and are typically not recognized during the early phases of drug development. This is particularly true if studies are conducted in populations where the genetic risk allele(s) associated with such reactions is not prevalent. These reactions are typically recognized in the 5-year post-marketing phase of drug development, after significant investment has been made in research and development. IM-ADRs have contributed to post-marketing drug withdrawal in a significant number of cases. Studies to define the biochemical and structural basis of severe IM-ADRs are providing assays to detect drug-HLA and drug-TCR interactions as well as the presentation of drug-induced neo-antigens by specific HLA alleles. Until we are able to understand and predict the additional factors that are necessary for the IM-ADR to occur, such as heterologous immunity, sole reliance on pre-clinical biochemical and structural approaches for screening drug compounds is likely to have an unacceptably low positive predictive values for the prediction of IM-ADR in vivo.146, 147 Advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of IM-ADRs will facilitate the development of early screening strategies to identify compounds with high likelihood of eliciting an ADR and this will, in turn, improve drug safety, improve the efficiency of drug design, and reduce the cost of drug development.

Supplementary Material

Blue Box.

What do we know?

Certain adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are strongly associated with variation in the HLA genes. Examples include the associations between carriage of the HLA-B*57:01 allele and abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome, the HLA-B*15:02 allele and carbamazepine-associated SJS/TEN, and the HLA-B*58:01 allele and allopurinol-associated SJS/TEN, among others.

Models that explain how a small molecule pharmaceutical compound might interact with MHC proteins include the hapten/prohapten model, the pharmacological interaction (p-i) model, and the altered peptide repertoire model.

Many of the associations between an ADR and HLA class I and/or II alleles are characterized by a high negative predictive value (approaching 100% in many cases) and this feature makes screening for the risk allele and exclusion of drug therapy for carriers a feasible approach to eliminate these reactions in at risk populations. This strategy has been applied in the clinical setting for abacavir, carbamazepine, and, more recently, allopurinol with marked reduction in the incidence of these ADR.

The positive predictive values (PPV) for many of these associations is <5% which suggests that factors other than HLA gene carriage are required for the T-cell mediated DHR to occur.

What is still unknown?

We do not know what factors, in addition to HLA risk allele carriage, are required for a T-cell mediated DHR to occur. An expanded model that incorporates the concepts of heterologous immunity with existing models that describe drug-peptide-HLA interactions (including the hapten/prohapten, p-i, and altered peptide repertoire models) is proposed. Direct evidence for this model is still lacking however, if proven, it is likely to explain many outstanding observations regarding T-cell mediated DHR including the incomplete PPV for HLA association, tissue specificity, short latency period (for some ADR), and long-lasting immunity to drugs in the absence of ongoing exposure.

Abbreviations used

- ADR

adverse drug reaction

- AGEP

acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CDR

complementarity-determining regions

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- DRESS

drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

- EBV

Epstein Barr virus

- GWAS

genome wide association study

- HHV

human herpesvirus

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- HSS

hypersensitivity syndrome

- HSV

herpes simplex virus

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- MHCI

major histocompatibility complex class I

- MHCII

major histocompatibility complex class II

- MPE

maculopapular eruption

- NPV

negative predictive value

- PPV

positive predictive value

- SJS

Stevens-Johnson syndrome

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- TCR

T cell receptor

- TEM

effector memory T cell

- TEN

toxic epidermal necrolysis

- VZV

varicella zoster virus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(15):1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hakkarainen KM, Hedna K, Petzold M, Hagg S. Percentage of patients with preventable adverse drug reactions and preventability of adverse drug reactions--a meta-analysis. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e33236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kongkaew C, Noyce PR, Ashcroft DM. Hospital admissions associated with adverse drug reactions: a systematic review of prospective observational studies. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2008;42(7):1017–1025. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suh DC, Woodall BS, Shin SK, Hermes-De Santis ER. Clinical and economic impact of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2000;34(12):1373–1379. doi: 10.1345/aph.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. Bmj. 2004;329(7456):15–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Burke JP. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277(4):301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277(4):307–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. The New England journal of medicine. 1994;331(19):1272–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rawlings MDTLW. Pathogenesis of adverse drug reactions. In: Davies DM, editor. Textbook of Adverse Drug Reactions. London: Oxford University Press; 1977. p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2000;356(9237):1255–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02799-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeil BD, Pundir P, Meeker S, et al. Identification of a mast-cell-specific receptor crucial for pseudo-allergic drug reactions. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature14022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavlos R, Mallal S, Ostrov D, et al. T Cell-Mediated Hypersensitivity Reactions to Drugs. Annual review of medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050913-022745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gueant JL, Romano A, Cornejo-Garcia JA, et al. HLA-DRA variants predict penicillin allergy in genome-wide fine-mapping genotyping. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;135(1):253–259. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez CA, Smith C, Yang W, et al. HLA-DRB1*07:01 is associated with a higher risk of asparaginase allergies. Blood. 2014;124(8):1266–1276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-563742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farber DL, Yudanin NA, Restifo NP. Human memory T cells: generation, compartmentalization and homeostasis. Nature reviews Immunology. 2014;14(1):24–35. doi: 10.1038/nri3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masopust D, Vezys V, Marzo AL, Lefrancois L. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science. 2001;291(5512):2413–2417. doi: 10.1126/science.1058867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sathaliyawala T, Kubota M, Yudanin N, et al. Distribution and compartmentalization of human circulating and tissue-resident memory T cell subsets. Immunity. 2013;38(1):187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu J, Koelle DM, Cao J, et al. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells accumulate near sensory nerve endings in genital skin during subclinical HSV-2 reactivation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204(3):595–603. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne JA, Butler JL, Cooper MD. Differential activation requirements for virgin and memory T cells. Journal of immunology. 1988;141(10):3249–3257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picker LJ, Singh MK, Zdraveski Z, et al. Direct demonstration of cytokine synthesis heterogeneity among human memory/effector T cells by flow cytometry. Blood. 1995;86(4):1408–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders ME, Makgoba MW, June CH, Young HA, Shaw S. Enhanced responsiveness of human memory T cells to CD2 and CD3 receptor-mediated activation. European journal of immunology. 1989;19(5):803–808. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtsinger JM, Lins DC, Mescher MF. CD8+ memory T cells (CD44high, Ly-6C+) are more sensitive than naive cells to (CD44low, Ly-6C−) to TCR/CD8 signaling in response to antigen. Journal of immunology. 1998;160(7):3236–3243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudolph MG, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. How TCRs bind MHCs, peptides, and coreceptors. Annual review of immunology. 2006;24:419–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prugnolle F, Manica A, Charpentier M, Guegan JF, Guernier V, Balloux F. Pathogen-driven selection and worldwide HLA class I diversity. Current biology : CB. 2005;15(11):1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qutob N, Balloux F, Raj T, et al. Signatures of historical demography and pathogen richness on MHC class I genes. Immunogenetics. 2012;64(3):165–175. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0576-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton R, Wilming L, Rand V, et al. Gene map of the extended human MHC. Nature reviews Genetics. 2004;5(12):889–899. doi: 10.1038/nrg1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidney J, Peters B, Frahm N, Brander C, Sette A. HLA class I supertypes: a revised and updated classification. BMC immunology. 2008;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hraber P, Kuiken C, Yusim K. Evidence for human leukocyte antigen heterozygote advantage against hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2007;46(6):1713–1721. doi: 10.1002/hep.21889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrington M, Nelson GW, Martin MP, et al. HLA and HIV-1: heterozygote advantage and B*35-Cw*04 disadvantage. Science. 1999;283(5408):1748–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thursz MR, Thomas HC, Greenwood BM, Hill AV. Heterozygote advantage for HLA class-II type in hepatitis B virus infection. Nature genetics. 1997;17(1):11–12. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White KD, Gaudieri S, Phillips E. HLA and the pharmacogenomics of drug hypersensitivity. In: Padmanabhan S, editor. Handbook of Pharmacogenomics and Stratefied Medicine. Elsevier, Inc.; 2014. pp. 437–465. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pichler W, Yawalkar N, Schmid S, Helbling A. Pathogenesis of drug-induced exanthems. Allergy. 2002;57(10):884–893. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;139(8):683–693. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-8-200310210-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park BK, Naisbitt DJ, Gordon SF, Kitteringham NR, Pirmohamed M. Metabolic activation in drug allergies. Toxicology. 2001;158(1–2):11–23. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naisbitt DJ, Gordon SF, Pirmohamed M, et al. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of sulphamethoxazole: demonstration of metabolism-dependent haptenation and T-cell proliferation in vivo. British journal of pharmacology. 2001;133(2):295–305. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padovan E, Mauri-Hellweg D, Pichler WJ, Weltzien HU. T cell recognition of penicillin G: structural features determining antigenic specificity. European journal of immunology. 1996;26(1):42–48. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pichler WJ, Beeler A, Keller M, et al. Pharmacological interaction of drugs with immune receptors: the p-i concept. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2006;55(1):17–25. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.55.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zanni MP, von Greyerz S, Schnyder B, et al. HLA-restricted, processing- and metabolism-independent pathway of drug recognition by human alpha beta T lymphocytes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;102(8):1591–1598. doi: 10.1172/JCI3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zanni MP, von Greyerz S, Schnyder B, Wendland T, Pichler WJ. Allele-unrestricted presentation of lidocaine by HLA-DR molecules to specific alphabeta+ T cell clones. International immunology. 1998;10(4):507–515. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnyder B, Mauri-Hellweg D, Zanni M, Bettens F, Pichler WJ. Direct, MHC-dependent presentation of the drug sulfamethoxazole to human alphabeta T cell clones. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100(1):136–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI119505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pichler WJWS. Interaction of small molecules with specific immune receptors: the p-i concept and its consequences. Current Immunology Reviews. 2014;10:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bharadwaj M, Illing P, Theodossis A, Purcell AW, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J. Drug hypersensitivity and human leukocyte antigens of the major histocompatibility complex. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2012;52:401–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavlos R, Mallal S, Phillips E. HLA and pharmacogenetics of drug hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13(11):1285–1306. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norcross MA, Luo S, Lu L, et al. Abacavir induces loading of novel self-peptides into HLA-B*57: 01: an autoimmune model for HLA-associated drug hypersensitivity. Aids. 2012;26(11):F21–F29. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328355fe8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ostrov DA, Grant BJ, Pompeu YA, et al. Drug hypersensitivity caused by alteration of the MHC-presented self-peptide repertoire. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(25):9959–9964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207934109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Illing PT, Vivian JP, Dudek NL, et al. Immune self-reactivity triggered by drug-modified HLA-peptide repertoire. Nature. 2012;486(7404):554–558. doi: 10.1038/nature11147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cutrell AG, Hernandez JE, Fleming JW, et al. Updated clinical risk factor analysis of suspected hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2004;38(12):2171–2172. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shapiro M, Ward KM, Stern JJ. A near-fatal hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir: case report and literature review. The AIDS reader. 2001;11(4):222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hetherington S, Hughes AR, Mosteller M, et al. Genetic variations in HLA-B region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir. Lancet. 2002;359(9312):1121–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mallal S, Nolan D, Witt C, et al. Association between presence of HLA-B*5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir. Lancet. 2002;359(9308):727–732. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07873-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips EJ, Sullivan JR, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Utility of patch testing in patients with hypersensitivity syndromes associated with abacavir. Aids. 2002;16(16):2223–2225. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211080-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rauch A, Nolan D, Thurnheer C, et al. Refining abacavir hypersensitivity diagnoses using a structured clinical assessment and genetic testing in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antiviral therapy. 2008;13(8):1019–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rauch A, Nolan D, Martin A, McKinnon E, Almeida C, Mallal S. Prospective genetic screening decreases the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions in the Western Australian HIV cohort study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006;43(1):99–102. doi: 10.1086/504874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, et al. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358(6):568–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saag M, Balu R, Phillips E, et al. High sensitivity of human leukocyte antigen-b*5701 as a marker for immunologically confirmed abacavir hypersensitivity in white and black patients. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008;46(7):1111–1118. doi: 10.1086/529382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lucas ALM, Strhyn A, Keane N, McKinnon E, Pavlos R, Moran E, Meyer-Pannwitt V, Gaudieri A, D’Orsogna L, Kalams S, Ostrov D, Buss S, Peters B, Mallal S, Phillips E. Abacavir-reactive memory T cells are present in drug naive individuals. PloS one. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117160. (accepted for publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phillips EJ, Wong GA, Kaul R, et al. Clinical and immunogenetic correlates of abacavir hypersensitivity. Aids. 2005;19(9):979–981. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171414.99409.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adam J, Eriksson KK, Schnyder B, Fontana S, Pichler WJ, Yerly D. Avidity determines T-cell reactivity in abacavir hypersensitivity. European journal of immunology. 2012;42(7):1706–1716. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chessman D, Kostenko L, Lethborg T, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class I-restricted activation of CD8+ T cells provides the immunogenetic basis of a systemic drug hypersensitivity. Immunity. 2008;28(6):822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adam J, Wuillemin N, Watkins S, et al. Abacavir induced T cell reactivity from drug naive individuals shares features of allo-immune responses. PloS one. 2014;9(4):e95339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knowles SR, Shapiro LE, Shear NH. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome: incidence, prevention and management. Drug safety : an international journal of medical toxicology and drug experience. 1999;21(6):489–501. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199921060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, et al. Medical genetics: a marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Nature. 2004;428(6982):486. doi: 10.1038/428486a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kulkantrakorn K, Tassaneeyakul W, Tiamkao S, et al. HLA-B*1502 strongly predicts carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Thai patients with neuropathic pain. Pain practice : the official journal of World Institute of Pain. 2012;12(3):202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mehta TY, Prajapati LM, Mittal B, et al. Association of HLA-B*1502 allele and carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome among Indians. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2009;75(6):579–582. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.57718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Then SM, Rani ZZ, Raymond AA, Ratnaningrum S, Jamal R. Frequency of the HLA-B*1502 allele contributing to carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions in a cohort of Malaysian epilepsy patients. Asian Pacific journal of allergy and immunology / launched by the Allergy and Immunology Society of Thailand. 2011;29(3):290–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Man CB, Kwan P, Baum L, et al. Association between HLA-B*1502 allele and antiepileptic drug-induced cutaneous reactions in Han Chinese. Epilepsia. 2007;48(5):1015–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]