Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the suitability of body mass index, waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio and aerobic fitness as predictors of cardiovascular risk factor clustering in children. A cross-sectional study was conducted with 290 school boys and girls from 6 to 10 years old, randomly selected. Blood was collected after a 12-hour fasting period. Blood pressure, waist circumference (WC), height and weight were evaluated according to international standards. Aerobic fitness (AF) was assessed by the 20-metre shuttle-run test. Clustering was considered when three of these factors were present: high systolic or diastolic blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high triglycerides, high plasma glucose, high insulin concentrations and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. A ROC curve identified the cut-off points of body mass index (BMI), WC, waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) and AF as predictors of risk factor clustering. BMI, WC and WHR resulted in significant areas under the ROC curves, which was not observed for AF. The anthropometric variables were good predictors of cardiovascular risk factor clustering in both sexes, whereas aerobic fitness should not be used to identify cardiovascular risk factor clustering in these children.

Keywords: anthropometric variables, aerobic fitness, cardiovascular risk, children

INTRODUCTION

In Brazil, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death, accounting for 29.4% (302682) of all deaths in the country in 2006 [1]. CVD is caused by an association between genetic and behavioural risk factors and can originate in childhood [2, 3]. The major CVD risk factors include heredity, obesity, smoking, physical inactivity, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, diabetes, insulin, and gender [4–6].

Obesity is associated with the development of hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, and premature death [7]. Body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference are considered strong indicators of overall adiposity and central obesity, respectively [2, 8]. The 85th and 95th percentiles of the population BMI are used to classify children and adolescents who are overweight and obese, respectively.

For the waist circumference, values above the 70th [9], 75th [10], and 50th to 57th [11] percentiles have been suggested as the appropriate cut-off points for predicting CVD risk factor clustering. According to Steinberger et al. [6], the atherosclerotic process is accelerated exponentially when CVD risk factors are clustered. This clustering may be present from childhood and tends to persist into adulthood [2].

Although low levels of aerobic fitness are associated with increased cardiovascular risk in adults, very few studies have evaluated this association in children [12, 13]. Due to the necessity for early intervention in children at increased risk of CVD, identifying the best predictors has aroused great interest. Even though several studies with similar methods and large samples have already been conducted [4, 5, 8, 14], there is no information regarding the Brazilian population on this subject. Liu et al. [5] and Yan et al. [15] clearly showed the necessity of determining cut-off points for a specific ethnic population, which can differ even within a single country.

Therefore, the objective of the present research was to identify cut-off points for the BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), and aerobic fitness for predicting CVD risk factor clustering in children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study participants were children aged 6 to 10 years who were enrolled in the 1st to 5th grades in public schools in the urban area of Itaúna, Minas Gerais, Brazil, constituting a random sample selected from a population of 4649 students.

To determine the minimum size required for the sample, a pilot study was conducted with 25 students of both genders who were 6 to 10 years old. The children's systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, glycaemia, and insulin levels were measured. For each variable, the maximal acceptable tolerance error was defined. For this purpose, the estimate of the population average obtained from values described in the literature was considered, thereby preserving the clinical relevance of the results. To calculate the minimum sample size for each variable, the respective sample standard deviation was used as a population estimate at a significance level of 5%. The maximum sample size was assumed to be within the minima obtained, which was the value of 228 individuals relative to the insulin variable (i.e., the limiting variable for sampling due to its highest variability). Thus, the sample size was set at a minimum of 228 students to meet the margin of error in population measurements for all variables of interest. Upon estimating a loss of 50%, the final sample was set to 456 children. This sample was stratified within each school so that the proportions of age and gender were maintained. Using the data obtained from each school, students in each grade were numbered in sequential order. Thereafter, a table of random numbers generated by the Excel 2003 software was used, and children were selected by the corresponding list created in each grade. This process was repeated until the number required to make up the sample for that age and gender for each school was reached.

The inclusion criteria were children between 6 and 10 years old and enrolled in the public state or municipal network. Children who had medical limitations and/or motor skill deficits that rendered them unable to perform the test were excluded.

Ethical considerations

A consent form was signed by the parents in advance. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (No. 0040.0.203.000-10) and the Universidade de Itaúna (No. 012/10) in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Procedures

Anthropometry

Body mass was measured with children wearing light clothes, on a Seca 803 digital electronic scale (Seca, Hamburg, Germany) with a maximum capacity of 150 kg and a precision of 0.1 kg. Height was measured on an Alturaexata vertical anthropometer (Alturaexata, São Paulo, Brazil) which was graduated in centimetres and had a precision of 0.001 m. Body weight and height were measured twice, and the mean was calculated. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the ratio of the total body mass in kilograms to the height in square metres. Waist circumference was measured using a Venosan tape measure (Venosan Brasil, Pernambuco, Brazil), 2 m in length, which was flexible, inelastic, and had a precision of 0.001 m. Waist circumference was measured at the end of a normal expiration and by setting a reference point located between the lowest rib and the top of the iliac crest [15].

Blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured using an automated blood pressure monitor (Omron HEM711, China) that has been validated for scientific purposes [16]. Three measurements were performed on the right arm after at least 5 minutes of rest, with the child seated and his or her legs and arms in a relaxed position. A 2-minute interval was provided between each measurement [12]. The mean of the three measurements was calculated.

Aerobic fitness

Aerobic fitness was evaluated by the maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), which was estimated indirectly using the Yo-Yo test [17]. This test consisted of running back and forth on a 20-m path with progressive intensity until exhaustion. The running pace was determined by a beep emitted by a sound system using a test-specific compact disc (CD). At each school, the distance was marked on either a sports field or another available area containing a paved surface. The initial running speed of the test was 8.5 km · h−1 and increased by 0.5 km · h−1 every minute until the child was unable to keep pace with two consecutive beeps. All of the children were verbally encouraged to achieve maximum stress during the test. For the calculation of VO2max in ml · kg−1 ·min−1, the following equation described by Leger and Gadoury [18] was used: VO2max = 31.025 + 3.238 (final test speed in km · h−1) - 3.248 (age in years) + 0.1536 (final speed x age). This test has been validated for children and adolescents (r = 0.76) [19].

Laboratory tests

After 12 hours of fasting, 10 ml of blood was collected into a disposable plastic syringe, and this amount was equally divided and distributed into two tubes. One of the tubes containing a fluoride anticoagulant was centrifuged to obtain plasma, and the fasting glucose level was measured by an automated enzymatic method in a Clinline 150 machine (Biomerieux, USA). After centrifugation, serum was obtained from the remaining 5 ml, and 500 µl was removed for analysis of total cholesterol and fractionation by the colorimetric enzymatic method, as well as for analysis of triglycerides by the automated enzymatic method. All tests were performed on the Clinline 150 machine (Biomerieux, USA). One millilitre serum volume was used for insulin analysis using the electrochemiluminescence method.

Statistical analysis

The criterion for the definition of clustering was the presence of three or more of the following risk factors in the same child (adjusted for age and gender): low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels; high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, glycaemia, or insulin levels; and high SBP or DBP. The cut-offs were set to below 45 mg · dl−1 for HDL cholesterol; above 100 mg · dl−1 for LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and glycaemia; and above the 80th percentile for blood pressure and insulin. The intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated for testing the anthropometric measures reliability. A ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve analysis was used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the variables BMI, waist circumference, WHtR ratio, and VO2max as predictors of CVD risk factor clustering. The area under the curve (AUC) measures the degree of separation between individuals affected and unaffected by a specific test. An AUC of 1 indicates perfect separation between affected and unaffected individuals, while an AUC of 0.5 indicates no discrimination between the test values. The cut-off point for each predictor variable was defined as the point where the greatest product was found between the sensitivity and specificity subtracted from 1. Next, for each variable in each gender, the percentile corresponding to the cut-off point was identified (table 4). This percentile was used to identify the cut-off values for each age in each gender. Those values were then smoothed by the use of least mean squares (LMS) regression by the software SAS. The LMS method involves summarizing percentiles at each age on the basis of Box-Cox power transformations, which are used to normalize the data [4]. A probability level of p < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. The SPSS for Windows statistical package version 17.0 was employed.

TABLE 4.

Cut-offs for the BMI, waist circumference, and WHtR for predicting CVD risk factor clustering in girls and boys aged 6-10 years (n = 290).

| Age (years) | BMI (kg · m−2) | WC (cm) | WHtR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | |

| 6 | 15.48 | 15.07 | 54.17 | 58.34 | 0.46 | 0.51 |

| 7 | 16.13 | 15.17 | 55.28 | 58.63 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| 8 | 16.15 | 15.35 | 61.70 | 62.16 | 0.46 | 0.49 |

| 9 | 16.40 | 15.47 | 58.93 | 61.38 | 0.43 | 0.46 |

| 10 | 17.76 | 16.97 | 64.73 | 66.57 | 0.46 | 0.48 |

Note: BMI= body mass index; WC = waist circumference; WHtR = waist circumference to height ratio.

RESULTS

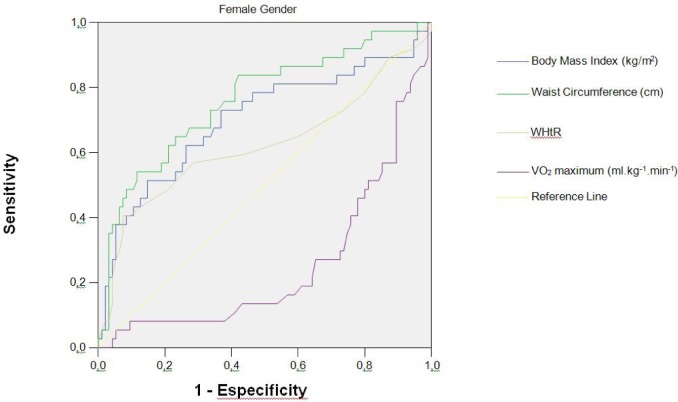

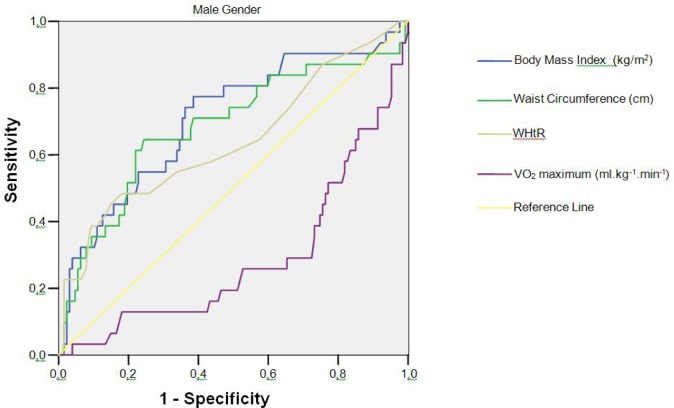

The descriptive characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The frequencies of CVD risk factors are presented in Table 2. The CVD risk factor clustering in the sample was 28.79% and 23.42% for girls and boys, respectively. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the three measures of waist circumference, height and body mass was, respectively: 0.997; 1.0 and 1.0 (p < 0.0001). Figures 1 and Figure 2 present the ROC curve for girls and boys, respectively. The optimal threshold values for predicting the high-risk group are those closest to the left corner in each figure, as determined by the choice between the intersection of the sensitivity and specificity curves. As presented in Table 3, the AUCs for the variables BMI, waist circumference, and WHtR ratio were significantly different from 0.5 (p < 0.001) in both genders, ranging from 0.62 to 0.76. The sensitivity and specificity varied between 48.4% and 81.9% for both genders. The AUCs for VO2max were 0.253 for the girls and 0.287 for the boys, indicating that this variable cannot be considered a strong predictor for CVD risk factor clustering in this sample (Figures 1 and 2). The cut-off values derived from the ROC curve (by age and gender) are presented in Table 4. These values are those above which there is increased likelihood of the child presenting a clustering of CVD risk factors.

TABLE 1.

Anthropometric characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors in boys and girls aged 6-10 years (n = 290).

| Variable | Girls (n = 132) | Boys (n = 158) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 8.25 ± 1.35 | 8.25 ± 1.33 |

| Height (m) | 1.32 ± 0.09 | 1.33 ± 0.10 |

| Body mass (kg) | 29.96 ± 8.86 | 31.60 ± 8.86 |

| BMI (kg · m−2) | 16.91 ± 3.56 | 17.46 ± 3.27 |

| WC (cm) | 59.19 ± 9.03 | 61.30 ± 9. 04 |

| WHtR | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.46 ± 0.06 |

| VO2max (ml · kg−1 · min−1) | 49.92 ± 3.08 | 52.04 ± 3.62 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 94.80 ± 9.93 | 95.81 ± 11.38 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 59.26 ± 8.46 | 57.50 ± 8.94 |

| Total cholesterol (mg · dl−1) | 171. 35 ± 30.35 | 169.34 ± 27.94 |

| LDL (mg · dl−1) | 103.69 ± 26.95 | 100.30 ± 27.95 |

| HDL (mg · dl−1) | 50.18 ± 10.62 | 53.09 ± 10.91 |

| Triglycerides (mg · dl−1) | 87.40 ± 39.46 | 79.77 ± 33.47 |

| Glycemia (mg · dl−1) | 88.74 ± 7.92 | 88.31 ± 8.19 |

| Insulin (µUI · ml−1) | 5.81 ± 5.44 | 4.80 ± 3.96 |

Note: values are mean ± standard deviation; BMI= body mass index; WC = waist circumference; WHtR = waist circumference to height ratio; VO2max = maximum oxygen consumption; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; HDL = high-density lipoprotein.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in boys and girls aged 6-10 years (n = 290).

| SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | HDL (mg · dl−1) | LDL (mg · dl−1) | Triglycerides (mg · dl−1) | Glycemia (mg · dl−1) | Insulin (µUI · ml−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | n /% | ||||||

| 6 (21) | 5/23.8 | 4/19.1 | 6/28.6 | 11/52.4 | 1/4.8 | 1/4.8 | 5/23.8 |

| 7 (18) | 4/22.2 | 4/22.2 | 6/33.3 | 9/50.0 | 3/16.7 | 1/5.6 | 4/22.2 |

| 8 (26) | 5/19.2 | 6/23.1 | 6/23.1 | 11/42.3 | 9/34.6 | 1/3.9 | 6/23.1 |

| 9 (41) | 9/21.9 | 9/21.9 | 15/36.6 | 28/68.3 | 14/34.2 | 2/4.9 | 9/22.0 |

| 10 (26) | 5/19.2 | 6/23.1 | 7/26.9 | 17/65.4 | 10/38.5 | 1/3.9 | 6/23.1 |

| Total (n = 132) | 28/21.2 | 29/22.0 | 40/30.3 | 76/57.6 | 37/28.0 | 6/4.6 | 30/22.7 |

|

| |||||||

| Boys | |||||||

| 6 (19) | 4/21.1 | 4/21.1 | 5/26.3 | 7/36.8 | 6/31.6 | 1/5.3 | 4/21.1 |

| 7 (32) | 7/21.9 | 7/21.9 | 8/25.0 | 15/46.9 | 5/15.6 | 5/15.6 | 7/21.9 |

| 8 (34) | 7/20.5 | 7/20.6 | 8/23.5 | 16/47.1 | 11/32.4 | 0/0 | 7/20.6 |

| 9 (37) | 8/21.6 | 8/21.6 | 6/16.2 | 17/46.0 | 4/10.8 | 0/0 | 8/21.6 |

| 10 (36) | 8/22.2 | 8/22.2 | 9/25.0 | 20/55.6 | 6/16.7 | 2/5.6 | 8/22.2 |

| Total (n = 152) | 34/21.5 | 34/21.5 | 36/22.8 | 75/47.5 | 32/20.3 | 8/5.1 | 34/21.5 |

Note: LDL = low-density lipoprotein; HDL = high-density lipoprotein.

FIG. 1.

ROC curve for BMI, waist circumference, WHtR (waist circumference to height ratio) and VO2max with CVD risk factor clustering in girls aged 6-10 years (n = 132).

FIG. 2.

ROC curve for the BMI, waist circumference, WHtR (waist circumference to height ratio) and VO2max with CVD risk factor clustering in boys aged 6-10 years (n = 158).

TABLE 3.

Results of ROC curve analysis for predicting cut-offs for the waist circumference, BMI, WHtR, and VO2max in predicting CVD risk factor clustering in girls and boys aged 6-10 years (n = 290).

| AUC | 95% CI | Percentile | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | |||||

| Girls | 0.70 | 0.59 - 0.81 | 52.9 | 73.0 | 63.2 |

| Boys | 0.71 | 0.60 - 0.82 | 53.7 | 74.4 | 61.4 |

|

| |||||

| WC | |||||

| Girls | 0.76 | 0.67 - 0.86 | 65.0 | 64.9 | 76.8 |

| Boys | 0.68 | 0.57 - 0.80 | 67.6 | 64.5 | 75.6 |

|

| |||||

| WHtR | |||||

| Girls | 0.62 | 0.50 - 0.74 | 63.5 | 56.8 | 71.6 |

| Boys | 0.64 | 0.52 - 0.76 | 75.7 | 48.4 | 81.9 |

|

| |||||

| VO2max | |||||

| Girls | 0.25 | 0.16 - 0.35 | - | - | - |

| Boys | 0.29 | 0.18 - 0.39 | - | - | - |

Note: ROC = receiving operating characteristic; BMI= body mass index; WC = waist circumference; WHtR= waist circumference to height ratio; VO2max = maximum oxygen consumption.

DISCUSSION

The cut-off points found for the BMI, waist circumference, and WHtR are considered strong predictors because between 48.4% and 74.4% of the children were correctly classified as having a high score for CVD risk (sensitivity), while between 61.4% and 81.9% were correctly classified as not having a high risk of CVD (specificity).

Similar values were found by Katzmarzyk et al. [4] (67% sensitivity and 75% specificity); Liu et al. [13] (75% to 83.3% sensitivity and 73.7% to 67.2% specificity); and Maffeis et al. [20] (72.4% sensitivity and 79.1% specificity). Ribeiro et al. [21] found scores between 53.8% and 72.2% for sensitivity and between 45.5% and 58.5% for specificity in Brazilian children and adolescents when analyzing the BMI, waist circumference, and WHtR ratio as predictors of CVD risk in isolation.

In the present study, the AUC was similar to BMI (0.70 and 0.71) and waist circumference (0.76 and 0.68), whereas the WHtR ratios were slightly lower (0.62 and 0.64) but also significant. These values are similar to the data from Katzmarzyk et al. [4], whereas Liu et al. [5] found values greater than 0.81, and Maffeis et al. [20] determined values equal to 0.8. The BMI cut-off points in this study ranged from 15.48 to 17.76 kg · m−2 for girls and 15.07 to 16.97 kg · m−2 for boys; these values are slightly lower than those found in Bogalusa's study [4] (i.e., 16.1 to 18.3 kg · m−2 for girls and 16.3 to 17.8 kg · m−2 for boys).

The cut-offs for waist circumference in the present study (54.17 to 64.73 cm for girls and 58.34 to 66.57 cm for boys) are higher than those found by Katzmarzyk et al. [4] in American children (52.7 to 63.3 cm for girls and 53.5 to 64.4 cm for boys). A study performed with children in Hong Kong resulted in values similar to those of the present study [29]. Liu et al. [5, 13] found waist circumference cut-offs (57.2 to 68.5 cm for girls and 62.7 to 79.9 cm for boys) which are larger than those found in the present study, while Bergmann et al. [22] found values ranging from 58.25 to 65.85 cm for girls and 63.85 to 66.75 for boys (all 7 to 10 years old and in southern Brazil). These small differences in the cut-off points between different studies may be explained by the number of risk factors considered as a cluster, the cut-off points established for the risk factors, consideration of the cut-off points by age, possible variations due to ethnicity, and the method of statistical analysis.

The cut-offs for the WHtR ratio in the present study ranged from 0.43 to 0.46 for girls and from 0.46 to 0.51 for boys. For the Brazilian population, in which there is great variation in height, the WHtR ratio may be a more appropriate measure of distribution than the BMI and waist circumference separately. Another advantage of the WHtR ratio over other measures of adiposity is that it varies less between gender and age; hence, the mean values may be used as cut-offs for children of both genders and of different ages. However, Pereira et al. [23] found that, compared to WHtR ratio, waist circumference is a better predictor of CVD risk factors in Brazilian adolescents.

Although most investigators have considered three or more CVD risk factors as a cluster [4, 5, 15], some researchers have used quartiles or quintiles of risk scores on a continuous scale [11–13], while others have studied the ability of predictor variables for each risk factor of CVD, in isolation [21, 24, 25]. Regarding the cut-off points for each risk factor, some investigators have used percentiles [4, 7, 11, 12], others have used fixed points [24], and still others have employed fixed cut-offs for certain variables and percentiles for other variables [5, 20, 21]. The percentiles considered as cut-offs have varied from the 75th to the 95th percentiles in different studies.

In the present study, we used fixed values for HDL and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and glycaemia, and over the 80th percentile (based on age and gender) for insulin, SBP, and DBP. These cut-offs points are considered desirable for the paediatric population according to Guideline I for Prevention of Atherosclerosis in Childhood and Adolescence [3]. Although the choice of these cut-offs may have contributed to high rates of CVD risk factor clustering (28.79 and 23.42% for girls and boys, respectively), we believe that the values indicated as “desirable” in the literature should be used for such studies.

According to our results, aerobic fitness could not be considered as a strong predictor of CVD risk factor clustering (AUC less than 0.5 for both genders). Significant AUCs (0.67 and 0.68) for aerobic fitness and CVD risk factors have been determined by Ruiz et al. [26]. There is strong scientific evidence for the association between aerobic fitness and CVD risk factors in adults, but paediatric studies are limited in numbers. Negative, significant, and moderate-to-high associations have been found in children [11, 26–29]. Kriemler et al. [13] demonstrated that, for each one-stage increase in the result of the Yo-Yo test, there was an 8% reduction in the sum of four skinfolds and a 6% reduction in the homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index, which is considered an indicator of insulin resistance.

Jago et al. [14] indicate a limited effect of aerobic fitness levels on CVD risk factors as a result of an exercise programme intervention when body mass is considered. During the field test used in the present investigation, subjects were requested to transport their body mass, which may have reduced the impact of aerobic fitness levels in our results [11–13]. Furthermore, it is possible that the ROC curve analysis performed here did not consider aerobic fitness to be a good predictor of CVD risk factor clustering because of the low variation coefficient of VO2max. This low amplitude of VO2max values observed in our sample may be explained by the specific features of the aerobic test used and its prediction equation. However, the choice of a field test in the present investigation was based on the observation of Ruiz et al. [26], who stated that “in some circumstances, field tests may be the best option because a large number of subjects can be tested at the same time, they are simple, safe and often the only feasible method.”

Although our selection of subjects was randomized and the sample was representative for the population, the low number of subjects within each age category may cause imprecise estimations. However, the use of a younger age range adds new information on a less studied population which shows an increasingly higher incidence of risks for CVD. Data were also obtained from a population with ethnic characteristics which differ from those of most studies available in the literature. This brings a special relevance, considering the importance of analyzing different socio-economic, ethnic and cultural aspects of the studied populations to better comprehend the impact of different risk factors on CVD development during childhood and adolescence [5, 15, 30]. The interpretation of our results is limited by its cross-sectional nature. The ideal study design to verify the real predictive ability of anthropometric variables and aerobic fitness should include a follow-up over many years.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study corroborated the use of BMI, waist circumference, and the WHtR ratio as predictors of CVD risk factor clustering and identified the respective cut-offs in children. Aerobic fitness was not a strong predictor in this study, although this variable deserves greater attention in future studies on this matter because of the incontrovertible evidence regarding the important role of aerobic fitness in preventing CVD risk factors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children and parents for their kind participation. We thank André Gustavo Pereira de Andrade for contribution on the statistical analysis. This work was supported by FAPEMIG and by the Universidade de Itaúna.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malta DC, Moura L, Souza FM, Rocha FM, Fernandes FM. In: Doenças crônicas não-transmissíveis: mortalidade e fatores de risco no Brasil, 1990 a 2006. Saúde Md., editor. Brasilia: 2009. pp. 337–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camhi SM, Katzmarzyk PT. Tracking of cardiometabolic risk factor clustering from childhood to adulthood. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5(2):122–9. doi: 10.3109/17477160903111763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Back Giuliano Ide C, Caramelli B, Pellanda L, Duncan B, Mattos S, Fonseca FH. [I guidelines of prevention of atherosclerosis in childhood and adolescence] Arq Bras Cardiol. 2005;85(Suppl 6):4–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katzmarzyk PT, Srinivasan SR, Chen W, Malina RM, Bouchard C, Berenson GS. Body mass index, waist circumference, and clustering of cardiovascular disease risk factors in a biracial sample of children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):e198–205. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu A, Hills AP, Hu X, Li Y, Du L, Xu Y, et al. Waist circumference cut-off values for the prediction of cardiovascular risk factors clustering in Chinese school-aged children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinberger J, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Hayman L, Lustig RH, McCrindle B, et al. Progress and challenges in metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2009;119(4):628–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro JC, Guerra S, Oliveira J, Teixeira-Pinto A, Twisk JW, Duarte JA, et al. Physical activity and biological risk factors clustering in pediatric population. Prev Med. 2004;39(3):596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrantes MM, Lamounier JA, Colosimo EA. Overweight and obesity prevalence among children and adolescents from Northeast and Southeast regions of Brazil. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2002;78(4):335–40. in Portuguese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreno LA, Pineda I, Rodriguez G, Fleta J, Sarria A, Bueno M. Waist circumference for the screening of the metabolic syndrome in children. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91(12):1307–12. doi: 10.1080/08035250216112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savva SC, Tornaritis M, Savva ME, Kourides Y, Panagi A, Silikiotou N, et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio are better predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in children than body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(11):1453–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Rizzo NS, Villa I, Hurtig-Wennlof A, Oja L, et al. High cardiovascular fitness is associated with low metabolic risk score in children: the European Youth Heart Study. Pediatr Res. 2007;61(3):350–5. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318030d1bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderssen SA, Cooper AR, Riddoch C, Sardinha LB, Harro M, Brage S, et al. Low cardiorespiratory fitness is a strong predictor for clustering of cardiovascular disease risk factors in children independent of country, age and sex. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(4):526–31. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328011efc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kriemler S, Manser-Wenger S, Zahner L, Braun-Fahrlander C, Schindler C, Puder JJ. Reduced cardiorespiratory fitness, low physical activity and an urban environment are independently associated with increased cardiovascular risk in children. Diabetologia. 2008;51(8):1408–15. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jago R, Drews KL, McMurray RG, Baranowski T, Galassetti P, Foster GD, et al. BMI change, fitness change and cardiometabolic risk factors among 8th grade youth. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2013;25(1):52–68. doi: 10.1123/pes.25.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan W, Yao H, Dai J, Cui J, Chen Y, Yang X, et al. Waist circumference cutoff points in school-aged Chinese Han and Uygur children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(7):1687–92. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grim CE, Grim CM. Omron HEM-711 DLX home Blood pressure monitor passes the European Society of Hypertension International Validation Protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13(4):225–6. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3282feebd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leger L, Lambert J, Goulet A, Rowan C, Dinelle Y. Capacite aerobie des quebecois de 6 a 17 ans. Test navette de 20 metres avec paliers de 1 minute. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1984;9(2):64–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leger L, Gadoury C. Validity of the 20 m shuttle run test with 1 min stages to predict VO2max in adults. Can J Sport Sci. 1989;14(1):21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. Validation of two running tests as estimates of maximal aerobic power in children. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1986;55(5):503–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00421645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maffeis C, Banzato C, Talamini G. Waist-to-height ratio, a useful index to identify high metabolic risk in overweight children. J Pediatr. 2008;152(2):207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribeiro RC, Coutinho M, Bramorski MA, Giuliano IC, Pavan J. Association of the Waist-to-Height Ratio with Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children and Adolescents: The Three Cities Heart Study. Int J Prev Med. 2010;1(1):39–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergmann GG, Gaya A, Halpern R, Bergmann ML, Rech RR, Constanzi CB, et al. Waist circumference as screening instrument for cardiovascular disease risk factors in schoolchildren. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2010;86(5):411–6. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira PF, Serrano HMS, Carvalho GQ, Lamounier JA, Peluzio MdCG, Franceschini SdCC, et al. Circunferência da cintura e relação cintura/estatura: úteis para identificar risco metabólico em adolescentes do sexo feminino? Rev Paul Pediatr. 2011;29:372–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng VW, Kong AP, Choi KC, Ozaki R, Wong GW, So WY, et al. BMI and waist circumference in predicting cardiovascular risk factor clustering in Chinese adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(2):494–503. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribeiro RC, Lamounier JA, Oliveira RG, Bensenor IM, Lotufo PA. Measurements of adiposity and high blood pressure among children and adolescents living in Belo Horizonte. Cardiol Young. 2009;19(5):436–40. doi: 10.1017/S1047951109990606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz J, Ortega F, Meusel D, Harro M, Oja P, Sjöström M. Cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with features of metabolic risk factors in children. Should cardiorespiratory fitness be assessed in a European health monitoring system? The European Youth Heart Study. J Public Health. 2006;14(2):94–102. [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuBose KD, Eisenmann JC, Donnelly JE. Aerobic fitness attenuates the metabolic syndrome score in normal-weight, at-risk-for-overweight, and overweight children. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):e1262–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resaland GK, Mamen A, Boreham C, Anderssen SA, Andersen LB. Cardiovascular risk factor clustering and its association with fitness in nine-year-old rural Norwegian children. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(1):e112–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schindler C, Siegert J, Kirch W. Physical activity and cardiovascular performance – how important is cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood? J Public Health. 2008;16(3):235–43. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esmaeilzadeh S, Kalantari H, Nakhostin- Roohi B. Cardiorespiratory fitness, activity level, health-related anthropometric variables, sedentary behaviour and socioeconomic status in a sample of Iranian 7-11 year old boys. Biol Sport. 2013;30(1):67–71. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1029825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]