Abstract

The aim of this study was to analyse the acid-base balance and partial pressure of blood gases of participants during a 100-km run. Fourteen experienced amateur ultramarathon runners (age: 43.36±11.83 years; height: 175.29±6.98 cm; weight: 72.12±7.36 kg) completed the 100-km run. Blood samples were taken before the run; after 25, 50, 75, and 100 km; and 12 and 24 hours after the run. There were significant differences (p<0.05) between the mean values registered for acid-alkaline balance, buffering alkalies, and current bicarbonate in each segment of the run, especially during the third, fourth, and fifth segments of the run (i.e., between 50 and 100 km), and there were only significant differences associated with buffering alkalies and current bicarbonate during the recovery. However, all the changes were within the physiological norm. A significant decrease in the compressibility of oxygen was observed after 100 km (from 92.80±15.67 to 88.36±13.71 mmHg) and continued during the recovery to 75.06±8.60 mmHg 12 h after the run. Also there was a decrease in saturation to a mean value of 93.78±3.10 at 12 h after the run. Generally the amateurs runners are able to adjust their running speed so as not to provoke a significant acid-base imbalance or lactate acid accumulation.

Keywords: blood parameters, long distance running, amateur runners

INTRODUCTION

The ability to sustain acid-base balance is one of the main factors that limits physical capacity. Therefore, measurements of acid-base balance are widely used in sports, especially when short, high-intensity exertion is involved. Numerous studies have been conducted on this subject. Previous studies have examined the effect of air temperature on anaerobic power and acid-base balance [1, 2, 3, 4] for instance. There have been relatively few publications regarding the acid-base balance and gas analysis in the blood of endurance athletes, especially ultramarathon runners, since the year 2000. Żołądź et al. [5] confirmed that these parameters could be useful for controlling the performance of marathon runners. However, there have recently been reports of an acute metabolic response during an ultramarathon race [6, 7]. Moreover, professional elite runners are able to adjust their running speed so that the acid-base balance remains undisturbed for a longer period of time [5]. Similarly, Costil and Fox [8] found that during a marathon, the mean running speed at which small changes in pH were maintained was equivalent to 80-86% of the maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max). However, not all of the factors that determine running speed during marathons have been identified [5]. Ultramarathon runners mostly depend on energy produced through aerobic pathways, and they have more active oxidative enzymes because of the predominance of type I muscle fibres [9]. However, many authors have studied the correlations between lactic acid accumulated in the blood during athletic performance and anaerobic threshold (AnT) or running velocity [10, 11, 12]. Föhrenbach et al. [13] measured lactate concentration and acid-base balance during a laboratory test and revealed that female and male marathon runners attained a steady state after 45 min of work and that their acidification was 3 mmol · l-1. However, small changes in the acid-base balance were found in blood samples taken while at rest after the runners had finished running. The present experiment [5] showed higher lactate concentration ([La]) without pH or bicarbonate changes in marathon runners during a field test. However, they suggested that acidification could have an influence on the utilization of different substrates and thus on the ability of the muscles to continue to work [5]. Boyd et al. [14], Cooke et al. [15] and Sahlin [16] have claimed that metabolic acidity has a direct or indirect effect on the utilization of substrates in muscles. Endurance performance can result in decreased haemoglobin (Hb) saturation, which can lead to limited oxygen delivery to the organs and thus organ damage [17, 18, 19, 20]. Because of the effects of hypoxia, scientists emphasize the need for high-altitude training for marathon runners. However, only a few studies of acid-base balance and oxygen (pO2) or carbon dioxide compressibility (pCO2) have been conducted on amateur athletes during ultramarathons. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyse the acid-base balance of the blood of amateur runners during a 100-km run. The idea was to establish whether the participants were able to maintain a running speed at which the acid-base balance was not disturbed and whether there was a decrease in haemoglobin saturation that caused disorders of gas diffusion as well as damage to the lungs [17, 18, 19, 20]. Based on the evidence described above, it was assumed that most subjects would be able to adjust their running speed (intensity) so as not to provoke a significant acid-base imbalance or lactate concentration, which are factors that limit performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study protocols received ethical approval from the Ethical Committee of the Regional Medical Chamber. A total of 14 males volunteered for the study (age: 43.36±11.83 years; height: 175.29±6.98 cm; weight: 72.12±7.36 kg). All of them were experienced amateur ultramarathon runners and signed an informed consent form to participate in the study. All of the subjects had valid medical cards and received medical supervision during the experiment.

The 100-km run started at 7:30 am and finished (for the last runner) at 19:38 pm. The subjects repeatedly ran a designated route of 3300 m. The altitude was 20 m above sea level, and the altitude differences did not exceed 3 m. The running surface was made of asphalt. The weathr conditions are shown in table 1.

TABLE 1.

Weather conditions during the run.

| Time [hh:mm] |

Wind speed [m/s] |

Temperature [°C] |

Air humidity [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 07:00 | 0.7 | 4.4 | 88.8 |

| 08:00 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 88.6 |

| 09:00 | 0.9 | 5.3 | 87.5 |

| 10:00 | 0.9 | 6.0 | 85.6 |

| 11:00 | 0.9 | 6.6 | 82.9 |

| 12:00 | 0.9 | 6.6 | 82.8 |

| 13:00 | 1.1 | 6.5 | 83.2 |

| 14:00 | 0.8 | 6.4 | 84.1 |

| 15:00 | 0.8 | 6,2 | 85.1 |

| 16:00 | 1.0 | 5.6 | 87.6 |

| 17:00 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 88.5 |

| 18:00 | 1.1 | 5.1 | 88.9 |

| 19:00 | 1.2 | 5.1 | 89.1 |

| 20:00 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 89.1 |

The shortest time required to complete the 100-km run was 9 hours and 11 minutes, and the longest time was 12 hours and 8 minutes (the time did not include the 1-min breaks for taking blood samples). The run times and break times between the courses were measured with a stopwatch (Timex, Switzerland, 2009), and the time results after each lap were shown on a board at the starting line. Running speed was measured individually by dividing the distance (each 25 km) and the time. Each participant was dressed in trainers, a t-shirt, a track suit (a cotton sweatshirt and pants), gloves, and a cap (made of natural fibres). The participants’ individual clothing preferences were accepted. Each of the runners was equipped with a portable heart rate monitor (Polar Electro, OY, Finland), which measured heart rate in 5 s intervals. Twelve hours before the experiment, the subjects ate supper. After resting for the night, they ate a light breakfast of their choice at 6:30 am. During the run, the runners nourished themselves with prepared food and drinks served from a special post. The meal included water with a low mineral content, high-energy drinks, sandwiches with cheese or ham, high-energy bars, and bananas.

Fingertip capillary blood samples were taken directly before the run; after 25, 50, 75, and 100 km; and 12 and 24 hours after the run. Both individual and group mean values were analysed in reference to physiological norms for the following parameters: acid-alkaline balance (pH; 7.35-7.45), depletion of base excess in the extracellular fluid (BEecf -2.3-2.3 mmol · l-1), current bicarbonate (HCO3act; 21-27 mmol · l-1), partial pressure of oxygen (pO2; 75-100 mmHg), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2; 32-45 mmHg), haemoglobin saturation with oxygen (O2sat; 95-98%), and lactate concentration (0.5-2.22 mmol · l-1) [21]. An ABL 835 FLEX type analyser (Radiometer Medical ApS brand, Denmark) was used for blood gasometry. The samples were analysed for lactate using an enzymatic method (Randox lactate analyser) at 37°C with an EPOLL 20 spectrophotometer (Serw-med s.c. brand, Poland, 2006). The weather conditions during the marathon run are presented in table 1.

The results are expressed as mean values and standard deviations. The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to assess the similarity of the distribution of the variable to the normal distribution. The Levene test was used to verify the homogeneity of the variance. For homogeneous results, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc HSD Tukey's test were applied to identify significantly different results. For heterogeneous results, Friedman's ANOVA right tail probability test post hoc were applied. The significance level was set at p<0.05. The results were analysed using Statistica 9.0 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma).

RESULTS

The mean running speed decreased with each repetition of the course and the lowest value was registered during the final stage of the marathon (from 75-100 km). A similar pattern was evident for heart rate and %HRmax (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Heart rate and running speed of the amateur ultramarathon runners (mean±SD) during sequential sections of the 100-km run.

| I 0-25 km |

II 0-25 km |

III 51-75 km |

IV 76-100 km |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V [km·h-1] | 10.44 ± 0.72*1-3,4 | 9.72 ± 0.97*2-4 | 9.36 ± 1.29 | 8.64 ± 1.08 |

| HR [bpm] | 145 ± 7.5 | 148 ± 6.55*2-4 | 143 ± 5.78 | 137 ± 3.89 |

| % HRmax | 78 ± 4.27 | 80 ± 3.65*2-4 | 78 ± 2.75 | 74 ± 2.07 |

Note: significant differences at p≤0.05

There was a significant decrease in the mean values registered for BEecf and HCO3act especially during the third, fourth, and fifth segments of the run (i.e., between 50 and 100 km), and there was only a significant increase associated with BEecf and HCO3act during the recovery. Although the changes were significant, they did not exceed the normal physiological reference values, which would indicate disturbances in the acid-base balance.

The gasometry results for the capillary blood samples (pO2, pCO2, O2sat) suggested that some ventilatory problems or diffusion impairments occurred in the subjects during the run. A significant decrease in the compressibility of oxygen was observed after 100 km and continued during the recovery. The lowest values for blood saturation with oxygen were registered after 12 h of recovery (93.78±3.10%) (table 3).

TABLE 3.

Changes in the mean acid-alkaline balance values of the marathon runners during the 100-km run and after 12 h and 24 h of recovery.

| I 0 km |

II 0-25 km |

III 26-50 km |

IV 51-75 km |

V 76-100 km |

VI 12 h rest |

VII 24 h rest |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEecf [mmol·l-1] |

-1,36 ± 1,22 |

-0,95 ± 1,31 |

-0,49*5

± 1,10 |

-0,98 ± 1,33 |

-2,18*6,7

± 1,97 |

0,11 ± 1,33 |

-0,26 ± 0,82 |

| HCO3act [mmol·l-1] |

23,13 ± 1,21 |

23,33*6

± 1,39 |

23,77*5

± 1,23 |

23,08 ± 1,39 |

22,02*6,7

± 1,79 |

24,39 ± 1,30 |

24,09 ± 0,86 |

| PCO2

[mmHg] |

40,90*4,5

± 2,19 |

39,5 ± 2,80 |

39,96 ± 3,57 |

37,44*6,7

± 3,14 |

36,89*6,7

± 2,53 |

40,68 ± 2,25 |

40,91 ± 2,12 |

| PO2

[mmHg] |

92,80*6

± 15,67 |

87,66 ± 10,81 |

84,16*4

± 12,62 |

96,47*6,7

± 16,39 |

88,36 ± 13,71 |

75,06 ± 8,60 |

79,86 ± 12,53 |

| O2sat [%] |

97,04*6

± 1,40 |

96,71 ± 1,13 |

95,29*4

± 3,53 |

97,09*6,7

± 2,29 |

95,94 ± 2,92 |

93,78 ± 3,10 |

94,14 ± 3,94 |

Note: significant differences at p≤0.05

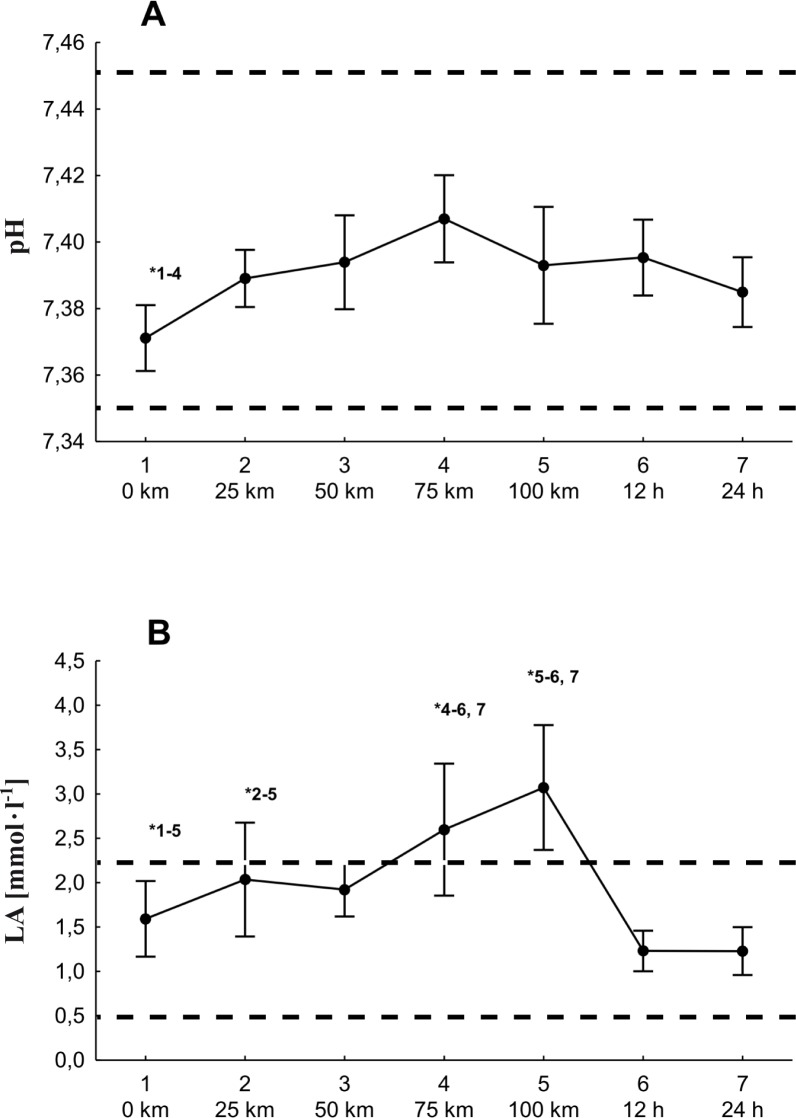

The pH value differed significantly from that obtained after running 75 km. Although the absolute value of the change was small (0.04), the direction of this change was surprising. After covering the distance, the pH value was significantly higher than the resting value (figure 1). The highest lactate concentration in the blood was 3.07 mmol · l-1, registered after the runners completed the full 100 km of the run. There were significant differences between successive parts of the run (figure 1).

FIG. 1.

Changes in the mean pH (A) and [La] (B) values of the marathon runners during the 100-km run and after 12 h and 24 h of recovery (… physiological norm).

*significant differences at p≤0.05.

DISCUSSION

Although statistically significant differences were found between the mean values of the indicators we examined, the acid-base balance did not exceed the normal physiological range in the marathon runners during the 100-km run. Only the [La] was slightly higher than the reference values at the end of the run. Because very few research data are available concerning acid-base balance in amateur and professional marathon runners, it is difficult to discuss the issue. It seems inappropriate to neglect the studies that have been conducted on acid-base balance in these runners.

The results presented in this article regarding the changes in the acid-base balance in the marathon runners revealed insignificant changes in the individual and mean values of pH, HCO3act, and BEecf in the blood samples; therefore, they cannot be recognized as factors that limit performance. The studies by Föhrenbach et al. [13] and Żołądź et al. [5], which address the changes in these parameters, provide similar results, although they used different methodologies and conducted the experiments under different conditions. Therefore, it seems that the changes in acid-base balance did not limit the running speed or the running time. Consequently, it appears that it was necessary to sustain the relative acid-base balance to complete the marathon run. Although the physical capacity of the tested subjects varied (due to the differences in fitness, age, physique, or individual predisposition that affected running speed and the time to complete the run), the subjects were able to sustain the acid-base balance in their blood. Therefore, it could be stated that both professionals and amateurs are able to adjust their running speed so that no acid-base imbalance occurs. In addition, there were no professional runners among our respondents.

The various temporary changes in the acid-base balance that occurred in the subjects during the experiment most likely appeared because the runners were free to choose their running speed and their nourishment. Previous studies that focused on the changes in acid-base balance were conducted by Forenbrach et al. [13] with male and female marathon runners performing in a laboratory. In addition, Żołądź et al. [5] studied the acid-base balance and the [La] in professional athletes during a field test. The authors reported that the mean lactate accumulation increased with the distance covered, but there were no considerable changes in the acid-base balance. However, other findings have suggested that mean running speed depends on [La] [8, 12, 20, 22]. These authors have reported that running speed is most strongly correlated with lactate concentration. Therefore, they concluded that marathon runners adjust their running speed to reach a level of oxygen uptake that prevents an exponential increase in [La] in the blood. The current results align with those of Żołądź et al. [5], who did not find a correlation between running speed and lactate accumulation. In contrast, the increase in [La] was accompanied by a decrease in running speed (using both individual and mean values). However, the decrease in runners’ running speed was disproportionate to the blood [La]. The substantial increase in lactate in the blood and the increase in heart rate could be the result of the incremental energy increases needed for running.

Although there have been numerous studies about the metabolism of marathon runners, only a few have addressed acid-base balance. This gap in the literature may be caused by two assumptions. First, some assume that there are only slight changes in the indicators of acid-base balance during endurance sports (lasting more than 2 h). Second, it has been assumed that it is crucial for a runner to prevent large changes in acid-base balance to be able to complete a run. However, it is still unknown whether the buffering capacity of the blood and the need to avoid disturbing the acid-base balance are the limiting factors for running speed. Furthermore, it is not known how large the disturbances can be during a running performance to maintain an effective rate of utilization (for example, by consuming sodium bicarbonate). However, it seems that excessive acidification and an acid-base imbalance could limit individual running speed. It is not clear which factors influence the running ability of marathon runners and to what extent. Assuming that lactate accumulation in the blood is one factor that determines the result of a run, it is unjustified to assume that this parameter is the only important factor and to ignore the influence of pH. The current study showed that there was a simultaneous increase in both pH and [La]. This result can be explained only by hypoxia of the organs (for example, the liver), which limits the utilization of [La] in the blood and intensifies the secretion of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and [La] in the blood in response to poor blood supply that results in damage to the organ [17, 18, 19, 23].

Therefore, an individual's ability to absorb and transport oxygen limits his or her ability to develop a faster running speed.

The present gasometry values showed a decrease in the mean values of the compressibility of oxygen (pO2) and blood oxygen saturation O2(sat.) as well as pCO2 in the subjects during a 100-km run. In three of the fourteen participants, the differences were significant, and the values were below the physiological norm. A decrease in pCO2 was also reported by Waśkeiwicz et al. [6] during a 24 h ultramarathon race. However, these factors had no considerable effect on running speed or intensity (expressed as %HRmax). The lack of an association shows the importance of running economy, even though the subjects were amateurs [11, 24, 251516, 22].

Nielsen [19] reported that hypoxemia occurs as a result of physical exercise. The author defined hypoxemia as a state of saturation below 95%. The results of the research, which examined rowers during recovery, revealed a decrease in pO2 that occurred earlier than the decrease in O2(sat.), similar to the results of our study. The compressibility of oxygen determines the extent to which the blood can become saturated with oxygen. However, there are more factors that influence the oxygen supplied to organs and tissues. One factor is body size. Large size is adversely associated with blood saturation. Nielsen [19] observed a low diffusion capacity in the lungs of the rowers, which might have resulted from damage to the alveolar membranes. Some changes in the blood, for example, the induced decay of basophiles, trigger a release of histamine, thereby limiting the decrease in pO2. Similarly, the increase in HCO3 reduces the desaturation.

Another reason for the reduced pO2 or O2(sat.) could be the limited diffusion of gases or the reduction in haemoglobin concentration [19]. We must also consider the rivalry for oxygen among the organs and tissues in cases of hypoxia. Changes in the distribution of blood also occur [19]. Ayus et al. [26] studied marathon runners who were hospitalized because of cerebral and pulmonary oedema and found their saturation levels to be less than 70%. After the run, the athletes suffered from nausea and vomiting. They were treated with ventilation; however, one person died. More precise examinations identified hyponatraemia as the cause of cerebral and pulmonary oedema in these patients. Therefore, administering bicarbonate reduced the pathological symptoms and allowed six out of seven patients to recover.

The low saturation levels that occur after exertion prompted scientists to study hypoxia in marathon runners and the effect of high-altitude training on endurance runners. We are convinced that measuring acid-base balance, especially ventilatory indicators, is very important, not only for success in sports but also for health reasons.

CONCLUSIONS

Considering the results we obtained from 14 marathon runners during a 100-km run, we drew the following conclusions in response to our questions:

There were no changes that exceeded physiological norms in the acid-base balance (and thus would limit running ability) of the subjects during the 100-km run.

The runners were able to adjust their running speed so that there were no disturbances in acid-base balance or excessive [La], which would have impaired their performance. A significant decrease in the oxygen saturation of the blood was observed after 12 h and 24 h of recovery, indicating damage to the pulmonary tissue or disorders in diffusion. This problem appears mainly after the completion of exercise.

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ebsjornsson L, Holm M, Sylwen J, Jansson CH. Different responses of skeletal muscle following sprint training in man and women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1996;74:375–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02226935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs J, Bar-Or O, Karlson J, Dotan R, Tesch P, Kaiser P, Inbar O. Changes in muscle metabolites in females with 30-s exhaustive exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:457–60. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlson J, Satin B, Lactate ATP, and CP in working muscles during exhaustive exercise in man. J Appl Physiol. 1979;29:596–602. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.29.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zychowska M. The effects of differentiated ambient temperature on physical and biochemical traits during repeated Wingate Test. J Hum Kinet. 1999;1:25–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Żołądź JA, Sargeant J, Emmerich J, Stoklosa J, Zychowski A. Changes in acid-base status of marathon runners during an incremental field test. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1993;67:71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00377708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waśkiewicz Z, Kłapcińska B, Sadowska-Krępa E, Czuba M, Kempa K, Kimsa E, Gerasimuk D. Acute metabolic responses to a 24-h ultra-marathon race in male amateur runners. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(5):1679–88. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2135-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kłapcińska B, Waśkiewicz Z, Chrapusta SJ, Sadowska-Krępa E, Czuba M, Langfort J. Metabolic responses to a 48-h ultra-marathon run in middle-aged male amateur runners. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113(11):2781–93. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2714-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costill DL, Fox EL. Energetics of marathon running. Med Sci Sports. 1969;1:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costill DL, Fink WJ, Pollock ML. Muscle fiber composition and enzyme activities of elite distance runners. Med Sci Sports. 1976;8:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollock ML. Submaximal and maximal working capacity of elite distance runners. Part I: Cardiorespiratory aspects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;301:310–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb38209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saltin B, Larsen H, Terrados N, Bangsbo J, Bak T, Kim CK, Svedenhag J, Rolf CJ. Aerobic exercise capacity at sea level and at altitude in Kenyan boys, junior and senior runners compared with Scandinavian runners. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1995;5:209–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1995.tb00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjodin B, Jacobs J. Onset of blood lactate accumulation and marathon running performance. Int J Sports Med. 1981;2:23–26. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fohrenbach R, Mader A, Hollmann W. Determination of endurance capacity and prediction of exercise intensities for training and competition in marathon runners. Int J Sports Med. 1987;8:11–18. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd AE, Giamber SR, Mager M, Lebovitz HZ. Lactate inhibition of lipolysis in exercising man. Metabolism. 1974;23:531–42. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(74)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooke R, Franks K, Luciani GB, Pate E. The inhibition of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction by hydrogen ions and phosphate. J Physiol. 1998;395:77–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahlin K. Muscle fatigue and lactic acid accumulation. Acta Physiol Scand. 1986;128:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dempsey JA, Hanson PG, Henderson KS. Exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia in healthy human subjects at sea level. J Physiol. 1984;55:161–75. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanon C, Lepretre PM, Bishop D, Thomas C. Oxygen uptake and blood metabolic responses to a 400-m run. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:233–40. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen HB. Arterial desaturation during exercise in man: implication for O2 uptake and work capacity. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13:339–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0838.2003.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K, Matsuura Y. Marathon performance, anaerobic threshold, and onset of blood lactate accumulation. J Appl Physiol. 1984;57:640–43. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.3.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomaszewski J. Laboratory diagnostics. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL; 2001. pp. 180–88. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhodes EC, McKenzie DC. Predicting marathon times from anaerobic threshold measurements. Phys Sport Med. 1984;12:95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorsen E, Sandsmark H, Ulltang E. Post-exercise reduction in diffusing capacity of the lung after moderate intensity running and swimming. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2006;33:103–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen HB. Kenyan dominance in distance running. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2000;136:161–70. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(03)00227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucia A, Esteve-Lanao J, Oliván J, Gómez-Gallego F, San Juan AF, Santiago C, Pérez M, Chamorro-Viña C, Foster C. Physiological characteristics of the best Eritrean runners-exceptional running economy. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006;31:530–40. doi: 10.1139/h06-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayus CJ, Varon J, Arieff AI. Hyponatremia, cerebral edema, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema in marathon runners. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:711–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]