Abstract

Ascariasis is a common helminthic disease worldwide, although Lithuania and other European countries are not considered endemic areas. The presence of the Ascaris worm in the biliary tree causes choledocholithiasis-like symptoms. We report a case of pancreatic duct ascariasis causing such symptoms. A 73-year-old Lithuanian woman underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) suspecting choledocholithiasis. Contrast injection into the common bile duct demonstrated a slightly dilated biliary tree without any filling defects, and the tail of an Ascaris worm protruding from the opening of the papilla Vater. The worm was captured by a snare but escaped deep into the duct. After a small wirsungotomy the worm was retrieved from the pancreatic duct. The patient received a 150 mg dose of levamisole orally repeated 7 days later and was discharged after complete resolution of symptoms. This first reported sporadic case of pancreatic duct ascariasis in Lithuania was successfully treated with ERCP and Levamisole.

Background

Ascariasis is a frequent human gastrointestinal tract helminthic disease caused by the parasitic round worm Ascaris lumbricoides, and mostly manifests in tropical developing countries.1 However, Lithuania and other European countries are not considered endemic areas. The adult form of A. lumbricoides usually stays in the intestinal lumen without causing any significant symptoms or severe health problems. Occasionally, the adult worm can migrate into the biliary tract through the papilla Vater and cause choledocoholithiasis-like symptoms or, extremely rarely, it can travel to the pancreatic duct causing pancreatitis-like symptoms.1 2

We present a case of pancreatic duct ascariasis with symptoms of biliary tract obstruction.

Case presentation

A 73-year-old Lithuanian woman with intense epigastric pain and mild jaundice that began 12 h earlier was referred to our hospital. She had a history of chronic cholecystitis due to which laparoscopic cholecystectomy had been performed 3 years earlier.

Investigations

Laboratory data showed mild leucocytosis of 11.2×109/L (reference range: 4.0–9.0×109/L) with no signs of eosinophilia. Other abnormal data included: bilirubin—40.5 mmol/L (reference range 5–21 mmol/L) with direct bilirubin of 27.7 mmol/L (reference range 0–5.3 mmol/L), γ-glutamyltransferase—124 U/L (reference range 0–36 U/L), alkaline phosphatase—172 U/L (reference range 40–150 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST)—1439 U/L (reference range 0–40 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)—939 U/L (reference range 0–40 U/L).

Abdominal ultrasound revealed common bile duct dilatation up to 12 mm, with suspected 8 mm diameter calculus in the duct. No ultrasound evidence of acute pancreatitis was found.

Treatment

The patient underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Contrast injection into the common bile duct demonstrated a slightly dilated biliary tree without any filling defects (figure 1). The duodenum and ampulla of Vater were without any visualised pathology. While cannulating the papilla, an Ascaris worm appeared in the papilla opening (figure 2). The protruding worm was captured by a snare but escaped and was completely hidden in the duct. Subsequent contrasting of the biliary tree showed no filling defects. Papillosphincterotomy (PST) with further gentle probing of the bile duct with a Dormia basket gave no results either, and the worm was not found. Suspecting Ascaris in the pancreatic duct, a small 3 mm wirsungotomy was performed. The worm was found and retrieved from the pancreatic duct using the Dormia basket. Control cholangiography showed no obstruction. There were no complications during and after the procedure.

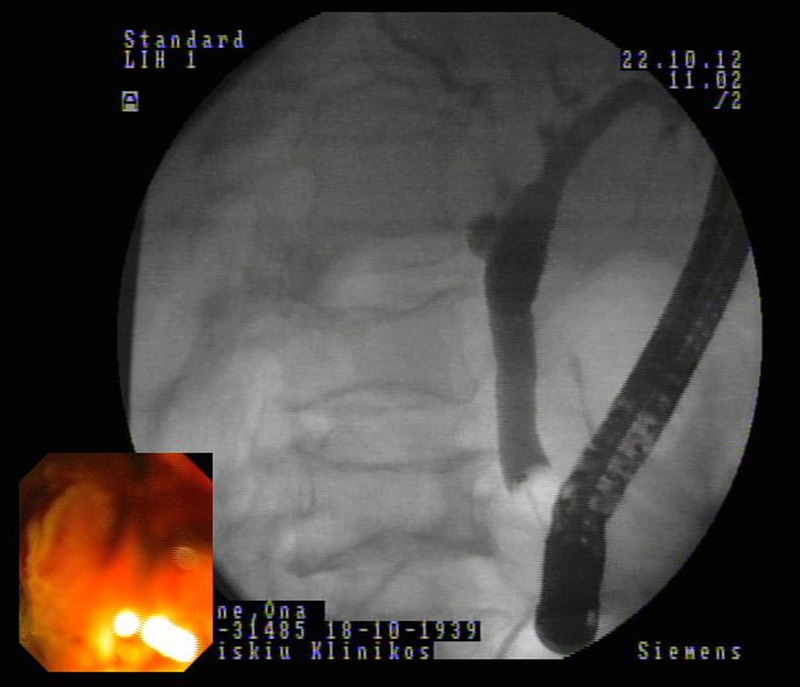

Figure 1.

The cholangiogram showing a slightly dilated biliary tree without any filling defect.

Figure 2.

Endoscopy revealing a worm seen from the papilla.

The patient was discharged after complete resolution of symptoms after receiving a single 150 mg dose of levamisole orally, which was repeated 7 days later on follow-up.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged 5 days after admission with complete resolution of all symptoms. A 150 mg dose of oral levamisole was repeated 7 days after the first one.

Discussion

Ascaris is one of the most common intestinal parasites in the world. Twenty-five per cent of the world's population is infected with this helminth.3 The geographic distribution of Ascaris is worldwide, and it is especially found in areas with warm and moist climates. Infection is most common in tropical and subtropical areas, particularly where sanitation and hygiene are poor.4 However, single cases and even case series of pancreatic ascariasis have been published in other non-endemic areas such as the USA,3–5 Spain,6 Switzerland,7 South Korea,8 China9 and Italy.10 Ascaris infection is not commonly found in Lithuania. According to the Lithuanian Centre of Infectious Diseases, in 2012, there were 240 reported cases of infection in this country with a population of around 3 million people.11 This is the first case reported in Lithuania of Ascaris migrating to the pancreatic duct.

The life cycle of A. lumbricoides starts after ingestion of the egg. After hatching, larvae migrate to the lungs through the intestinal wall via the portal and systemic circulation, penetrate the alveolar walls, ascend the bronchial tree to the throat, and are swallowed into the small intestine again, where they mature into adult worms.4

The disease may stay asymptomatic with ascarides in the lumen of small intestine. Symptoms can occur when helminths invade the biliary or pancreatic ducts. In case of severe infection, the mass of ascarides can cause bowel obstruction. Clinical signs depend on where the worm migrates: if it reaches the gall bladder—cholecystitis, and if it travels to the bile duct or pancreatic duct—cholangitis or pancreatitis, respectively, can be seen. Presentations of forms are biliary colic (56%), acute cholangitis (25%), acute cholecystitis (13%) and acute pancreatitis (6%), and, rarely, hepatic abscess or haemobilia.12 Furthermore, there are reports of duodenal perforation caused by ascariasis. Previous cholecystectomy or PST seems to be a risk factor for possible migration of ascarides into the biliary system, in case of infection.2–13 Our patient underwent cholecystectomy 3 years before the reported case.

The differential diagnosis of jaundice and cholangitis in endemic regions considers the possibility of ascariasis. However, in sporadic cases, such as that presented, the diagnosis was established incidentally during ERCP. Blood markers are not specific for ascariasis and rely more on common inflammation, mechanical jaundice or pancreatitis. Eosinophilia can be insignificant and appear only during the pulmonary stage of the disease.14 In our case, the patient had elevated blood levels of bilirubin, pointing to mechanical jaundice, and liver enzymes AST and ALT. Imaging studies include abdominal ultrasound, which is quite sensitive and specific for the diagnosis.3–13 In our case, Ascaris was interpreted as an 8 mm common bile duct stone, on ultrasound. Endosonography is recommended for differentials when the biliary tree is concerned or where there is pancreatic malignancy.15 16

ERCP is a diagnostic as well as a treatment procedure. ERCP combined with antihelminthic agents is the first-line treatment of biliary ascariasis.14 15 MR cholangiopancreatography can also be used for investigation of bile and pancreatic ducts.2–13 On the contrary, when ERCP is unsuccessful, a laparoscopic approach with further choledochotomy and extraction of the worm can be used.13 Laparotomy can also be performed in complicated cases, such as bowel perforation and peritonitis.16 In our case, the first attempt to extract Aascaris caused the worm to migrate back into the pancreatic duct, but, fortunately, it was successfully removed on the second try.

However, conservative treatment can be used alone without further invasion procedures.17 18 First choice drugs used for eradication of helminths are albendazole and mebendazole, and, alternatively, levamisole.14–18 In our case, invasive methods were essential because of suspected biliary obstruction. However, dead ascarides can induce chronic inflammation processes in the ductal mucosa, leading to strictures. Moreover, remnants of the dead worm can play the role of nuclei in biliary stone formation.15–19 Necrosis and perforation of the common bile duct or gall bladder are rare. However, the outcome can be fatal in cases of septicaemia associated with biliary and hepatic complications.8–20

Recurrence or reinfection in endemic areas occurs frequently. The risk of biliary ascariasis increases after cholecystectomy or PST.3–13 Antihelminthic therapies act against the adult worm but not against the larvae. Therefore, patients should be re-evaluated in 2–3 months following therapy with repeat stool microscopy.14–18 In our case, the eradication was successful, no recurrence was determined on the follow-up 3 months later.

Conclusion

This first reported sporadic case of pancreatic duct ascariasis in Lithuania was successfully treated with ERCP and levamisole.

Learning points.

This first reported sporadic case of pancreatic duct ascariasis in Lithuania was successfully treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and levamisole.

ERCP combined with antihelminthic agents is the first-line treatment of biliary ascariasis.

The presence of Ascaris worm in the biliary tract is considered in the differential diagnosis of mechanical jaundice in endemic areas, however, in sporadic cases, it can be found incidentally.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Michail Klimovskij at @drMaikl

Contributors: MK and AD performed the literature review and wrote the paper. ZK performed the procedure. SM revised the paper critically for important intellectual content and performed final approval of the version to be submitted.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rocha Mde S, Costa NS, Costa JC et al. CT identification of Ascaris in the biliary tract. Abdom Imaging 1995;20:317–19. 10.1007/BF00203362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng KK, Wong HF, Kong MS et al. Biliary ascariasis: CT, MR cholangiopancreatography, and navigator endoscopic appearance-report of a case of acute biliary obstruction. Abdom Imaging 1999;24:470–2. 10.1007/s002619900542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amog G, Lichtenstein J, Sieber S et al. A case report of ascariasis of the common bile duct in a patient who had undergone cholecystectomy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124:1231–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crompton DWT. Handbook of helminthiasis for public health. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulman A. Sonographic diagnosis and follow-up in a patient with pancreatic roundworms. A case report . S Afr Med J 1989;75:184–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casado-Maestre MD, Alamo-Martinez JM, Segura-Sampedro JJ et al. Ascaris lumbricoides as etiologic factor for pancreas inflammatory tumor. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2011;103:592–3. 10.4321/S1130-01082011001100008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maddern GJ, Dennison AR, Blumgart LH. Fatal Ascaris pancreatitis: an uncommon problem in the West. Gut 1992;33:402–3. 10.1136/gut.33.3.402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo KS, Song HG, Kim KO et al. Acute pancreatitis due to impaction of Ascaris lumbricoides in the pancreatic duct case report. Pancreas 2007;35:290–2. 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3180645da5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen D, Li X. Forty-two patients with acute Ascaris pancreatitis in China. J Gastroenterol 1994;29:676–8. 10.1007/BF02365456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangiavillano B, Carrara S, Petrone MC et al. Ascaris lumbricoides-induced acute pancreatitis: diagnosis during EUS for a suspected small pancreatic tumor. JOP 2009;10:570–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lithuanian center of AIDS and infectious diseases. http://www.ulac.lt. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanai FM, Al-Karawi MA. Biliary ascariasis: report of a complicated case and literature review. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2007;13:25–32. 10.4103/1319-3767.30462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jethwani U, Singh GJ, Sarangi P et al. Laproscopic management of wandering biliary ascariasis. Case Rep Surg 2012;2012:561563 10.1155/2012/561563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leder K, Weller PF, Ryan ET, et al. Ascariasis. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/ascariasis. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phisalprapa P, Prachayakul V. Ascariasis as an unexpected cause of acute pancreatitis with cholangitis: a rare case report from urban area. JOP 2013;14:88–91. 10.6092/1590-8577/1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarmast AH, Parray FQ, Showkat HI et al. Duodenal perforation with an unusual presentation: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis 2011;2011:512607 10.1155/2011/512607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonen KA, Mete R. A rare case of ascariasis in the gallbladder, choledochus and pancreatic duct. Turk J Gastroenterol 2010;21:454–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez AH, Regalado VC, Van den Ende J. Non-invasive management of Ascaris lumbricoides biliary tact migration: a prospective study in 69 patients from Ecuador. Trop Med Int Health 2001;6:146–50. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00657.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alam S, Mustafa G, Rahman S et al. Comparative study on presentation of biliary ascariasis with dead and living worms. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2010;16:203–6. 10.4103/1319-3767.65200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misra SP, Dwivedi M. Clinical features and management of biliary ascariasis in a non-endemic area. Postgrad Med J 2000;76:29–32. 10.1136/pmj.76.891.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]