Abstract

Background

Numerous studies from around the world have shown a positive association between case numbers and the quality of medical care. The evidence to date suggests that conformity to guidelines for the treatment of patients with breast cancer is better in German hospitals that have higher case numbers.

Methods

We used data obtained by an external program for quality assurance in inpatient care (externe stationäre Qualitätssicherung, esQS) for the years 2013 and 2014 to investigate seven process indicators in the area of breast surgery, including histologic confirmation of the diagnosis before definitive treatment, axillary dissection as recommended by the guidelines, and an appropriate temporal interval between diagnosis and operation. Case numbers were categorized with the aid of various threshold values. Moreover, subgroup analyses were carried out for patients under age 65, patients in good general health, patients without lymph-node involvement, and patients with a tumor size pT0 or pT1 or an overall tumor size less than 5 cm.

Results

Data on 153 475 patients from 939 hospitals were analyzed. Six of seven indicators had values that were better overall, to a statistically significant extent, in hospitals with higher case numbers. Although this relationship was not consistently seen, the worst results were generally found in the category with the lowest case numbers. Similar though less striking results were obtained in the subgroup analyses. An exception to the general finding was that, in hospitals with higher case numbers, the interval between diagnosis and operation was more often longer than three weeks.

Conclusion

Guideline adherence is higher in hospitals that treat more cases. The present study does not address the question whether this, in turn, affects morbidity or mortality. To improve process quality in peripheral hospitals, the quality assurance program should be continued.

Some 70 000 new cases of breast cancer each year make this particular cancer the most common one in women in Germany. A further 6500 patients are affected by ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (1). Stringent application of scientifically based standards in the treatment of breast cancer can overall result in a better individual prognosis in affected women as well as improvements in their quality of life (2).

Following on from a seminal study of the association between the number of surgical procedures and mortality (3), numerous studies have investigated the influence that the number of therapeutic procedures performed or the numbers of patients treated have on the quality of care in hospitals (3– 12). Many of these studies dealt with surgical procedures used to treat cancers, such as breast surgery (4, 10– 17). Most of these studies (4, 10, 11, 13– 17) investigated associations between case numbers and survival rates; their results mostly found a positive association between case numbers and the quality of the results (13– 17). Such volume effects may also be assumed for process quality in the surgical treatment of breast cancer (12, 18). The possible reasons that have been named for this include hospitals’ greater experience and routines and surgeons who have operated on more patients (3, 13). Furthermore it may be assumed that hospitals with greater case numbers are better placed to provide the necessary multidisciplinary treatment and infrastructure; for this reason, treatment in centers with large case numbers is favored (12, 19– 21). In Germany, one of the structural requirements for certified breast cancer centers is a minimum number of more than 100 primary cases per year at first certification (22).

In spite of the trend shown in different studies, the extent of the association and the direction of causality between the frequency of operations and the quality of care are not always straightforward, because the results depend, among other factors, on the procedure under analysis, the outcome measure, and the set threshold, and these may vary considerably (4– 6, 23). Furthermore, selection bias may provide an explanation for observed associations with survival rates, as, for example, patients with comparatively high risks may increasingly attend smaller hospitals (11). The present study analyzes the association between case numbers and process quality in breast surgery in Germany, using current data.

Methods

We used data from an external program for quality assurance in inpatient care (externe stationäre Qualitätssicherung, esQS) from the service sector breast surgery. Since 2002, it has been compulsory within the context of the esQS for all acute inpatient hospitals in Germany to maintain case related quality documentation for male and female patients with breast cancer and to pass this on to the responsible quality assurance office (24).

We based our analysis on fully inpatient cases having their first surgical procedure for a primary tumor and histology showing “invasive breast cancer” or “ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS),” with patients admitted in 2013 or 2014 and discharged between 1 January 2013 and 31 January 2015. The total number of cases included came to 153 475 (Table 1). In analogy to an earlier study investigating the association between hospital case numbers and mortality, we categorized the resulting case numbers by quintiles (7). The hospitals were ranked by case numbers and classified into five groups with roughly identical case numbers; the size of the groups was determined by the number of cases under consideration, not the number of hospitals (Table 1). The second form of categorization was done—taking our direction from the technical requirements for breast cancer centers (14)—on the basis of groups of case numbers defined previously. We defined categories <50 cases, 50–99 cases, 100–149 cases, and ≥150 cases per institution and per year (Table 1). By using these two forms of categorization, we classified 939 hospitals by case number categories. We calculated the quality indicators for each case number category. In order to test the association between case numbers and the results from the institutions, we used quality indicators relating to process quality. We used the current algorithms for the indicators of the esQS for the year 2014 (25), as long as they could be applied to the 2013 data. Indicator 2, “intraoperative specimen radiography with sonographic wire marking,” was calculated by using the algorithm for the year 2013 (26). We did not present the indicator “intraoperative specimen radiography with sonographic wire marking,” as a change of the algorithm with the 2013 specification could not yet be implemented. Furthermore, we did not report on indicators newly introduced in 2014.

Table 1. Description of study population for the purpose of defining case number categories: patients having their first open surgery on this breast for a primary tumor.

| Characteristics | Number of patients (%) | Characteristics | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in quintiles) | Sex | ||

| <51 years | 34958 (22.78%) | Female | 152364 (99.28%) |

| 51–58 years | 28110 (18.32%) | Male | 1111 (0.72%) |

| 59–66 years | 31340 (20.42%) | Type of cancer | |

| 67–75 years | 31948 (20.82%) | DCIS | |

| >75 years | 27119 (17.67%) | Invasive breast cancer | 138413 (90.19%) |

| ASA | First open surgery on this breast for a primary tumor | ||

| 1 | 40229 (26.21%) | n | 153475 (100%) |

| 2 | 85609 (55.78%) | ||

| 3 | 26852 (17.50%) | ||

| 4 | 737 (0.48%) | ||

| 5 | 48 (0.03%) | ||

| Defining case number categories on the basis of quintiles | |||

| Category (quintile) | Number of patients | Number of hospitals | |

| ≤105 | 30121 | 650 | |

| 106–162 | 31347 | 117 | |

| 163–227 | 31795 | 82 | |

| 228–326 | 30969 | 58 | |

| ≥327 | 29243 | 32 | |

| Total | 153475 | 939 | |

| Defining case number categories on the basis of case number groups defined beforehand | |||

| Category (case number groups) | Number of patients | Number of hospitals | |

| <50 | 11223 | 525 | |

| 50–99 | 17052 | 116 | |

| 100–149 | 24172 | 97 | |

| ≥ 150 | 101028 | 201 | |

| Total | 153475 | 939 | |

| Node status (TNM classification) in primary invasive breast cancer or DCIS and completed primary surgical therapy | Tumor size (TNM classification) in primary invasive breast cancer or DCIS and completed primary surgical therapy | ||

| pN0, ypN0 | 74667 (60.72%) | pT0, ypT0 | 3485 (2.83%) |

| pN1, ypN1 | 22839 (18.57%) | pT1, ypT1 | 60260 (49.01%) |

| pN2, ypN2 | 7726 (6.28%) | pT2, ypT2 | 36852 (29.97%) |

| pN3, ypN3 | 5076 (4.13%) | pT3, ypT3 | 5968 (4.85%) |

| pNX, ypNX | 12658 (10.29%) | pT4, ypT4 | 4854 (3.95%) |

| Total | 122966 (100.00%) | pTX, ypTX | 460 (0.37%) |

| pTis, ypTis | 11087 (9.02%) | ||

| Total | 122966 (100.00%) | ||

| Overall tumor size in primary DCIS and completed primary surgical therapy | |||

| ≤ 0.5 cm | 1905 (17.18%) | ||

| >0.5 cm bis 1 cm | 1888 (17.03%) | ||

| >1 cm bis 2 cm | 2741 (24.72%) | ||

| >2 cm bis 5 cm | 2801 (25.26%) | ||

| >5 cm | 959 (8.65%) | ||

| No data | 793 (7.15%) | ||

| Total | 11087 (100.00%) | ||

ASA 1 = normal healthy patient; ASA 2 = patient with mild systemic disease; ASA 3 = patient with severe systemic disease; ASA 4 = patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life; ASA 5 = moribund patient who is not expected to survive without operation. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ

The indicators were calculated for all patients of the hospitals included in the relevant category. The following list shows the indicators included in the analysis with their respective quality objective:

QI 1: Pretherapeutic histological confirmation of diagnosis: as many patients as possible with pretherapeutic histological confirmation of diagnosis by means of punch biopsy or vacuum biopsy during their first open surgery for primary invasive breast cancer or DCIS.

QI 2: Intraoperative specimen radiography with sonographic wire marking: as large a number of interventions as possible with intraoperative specimen radiography after wire marking using sonography.

QI 3: Primary axillary dissection in DCIS: as small a number of patients as possible with primary axillary dissection in DCIS and completed primary surgical treatment.

QI 4: Lymph node removal in DCIS and breast conserving treatment: as small a number of patients as possible having axillary lymph nodes dissected in DCIS and breast conserving treatment after completed primary surgical therapy.

QI 5: Indication for sentinel lymph node biopsy: as large a number of patients as possible having sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and without axillary dissection after completed primary surgical therapy and in lymph node–negative (pN0) invasive breast cancer.

QI 6: A time interval of less than 7 days between diagnosis and operation: as small a number of patients as possible with a time interval of less than 7 days between pretherapeutic histological diagnosis and date of surgery at first open procedure for primary invasive breast cancer or DCIS.

QI 7 Time interval of more than 21 days between diagnosis and operation: as few patients as possible with a time interval of more than 21 days between pretherapeutic histological diagnosis and date of surgery in first open procedure for primary invasive breast cancer or DCIS.

The baseline population considered in each indicator was restricted by two subgroups, and the indicators were newly calculated for the case number categories described in Table 1. The first subgroup for indicators 1, 2, and 5–7 refers to patients younger than 65 years with an ASA1 or ASA2, as per the ASA classification to assess preoperative risk, pN0 node status, and tumor size pT0 or pT1, according to the TNM classification. The second subgroup for indicators 3 and 4 includes patients younger than 65 with ASA1 or ASA2 and a total tumor size smaller than 5 cm.

The results of the quality indicators (QI) are shown as means with 95% confidence intervals, according to Wilson (27, 28). Additionally the results of indicators 5 (overall analysis) and 4 (subgroup analysis) per hospital, dependent on the respective case numbers of each hospital, were visualized as scatter plots, using Lowess regression (29, 30).

Results

We present the results of the different forms of categorization of hospitals by case numbers (Table 2, eTable). For all indicators except QI 7, “Time interval of more than 21 days between diagnosis and operation,” the overall analysis shows volume effects; in most cases the category of the lowest case numbers shows the worst results (Table 2). According to type of categorization—that is, categorizing the mean case numbers by hospital and year by quintiles or the case number groups defined beforehand—the results of the lowest category differs significantly from the results of the other category for four (QI1, QI2, QI5, QI6) and five (QI1, QI2, QI3, QI5, QI6) of the indicators under study. For example, hospitals with larger case numbers more often undertake pretherapeutic histological confirmation of diagnosis by using punch biopsy or vacuum biopsy than hospitals with smaller case numbers (QI 1).

Table 2. Means of the quality indicators by the different categories, differentiated by case number categories.

| Category (quintile) | Number of patients | Mean (95% CI) | Category (case number groups) | Number of patients | Mean (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QI 1 Pretherapeutic histological confirmation of diagnosis | |||||

| ≤105 | 28985 | 93.7 (93.4–93.9) | <50 | 10740 | 90.8 (90.3–91.4) |

| 106–162 | 30185 | 96.7 (96.4–96.8) | 50–99 | 16457 | 95.3 (95.0–95.6) |

| 163–227 | 30957 | 97.0 (96.8–97.2) | 100–149 | 23318 | 96.6 (96.3–96.8) |

| 228–326 | 30069 | 96.8 (96.6–97.0) | ≥ 150 | 98347 | 96.8 (96.7–97.0) |

| ≥327 | 28666 | 96.8 (96.5–97.0) | |||

| QI 2 Intraoperative specimen radiography with sonographic wire marking | |||||

| ≤105 | 6450 | 94.4 (93.8–95.0) | <50 | 1877 | 89.0 (87.5–90.3) |

| 106–162 | 8015 | 98.0 (97.7–98.3) | 50–99 | 4298 | 97.0 (96.4–97.4) |

| 163–227 | 9158 | 96.5 (96.1–96.9) | 100–149 | 5924 | 97.8 (97.4–98.2) |

| 228–326 | 9411 | 98.6 (98.4–98.9) | ≥ 150 | 31977 | 97.3 (97.1–97.4) |

| ≥327 | 11042 | 96.6 (96.2–96.9) | |||

| QI 3 Primary axillary dissection in DCIS | |||||

| ≤105 | 1976 | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | <50 | 564 | 2.5 (1.5–4.1) |

| 106–162 | 2808 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 50–99 | 1265 | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) |

| 163–227 | 3125 | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 100–149 | 2146 | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) |

| 228–326 | 3192 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | ≥ 150 | 10118 | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) |

| ≥327 | 2992 | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | |||

| QI 4 Lymph node biopsy in DCIS and breast conserving treatment | |||||

| ≤105 | 1478 | 17.2 (15.3–19.2) | <50 | 397 | 18.1 (14.7–22.2) |

| 106–162 | 2178 | 16.5 (15.0–18.1) | 50–99 | 985 | 16.4 (14.3–18.9) |

| 163–227 | 2407 | 13.8 (12.5–15.3) | 100–149 | 1649 | 17.0 (15.3–18.9) |

| 228–326 | 2367 | 16.0 (14.5–17.5) | ≥150 | 7578 | 14.3 (13.5–15.1) |

| ≤327 | 2179 | 12.5 (11.2–13.9) | |||

| QI 5 Indication for sentinel lymph node biopsy | |||||

| ≤105 | 14149 | 90.3 (89.8–90.8) | <50 | 5057 | 85.0 (83.9–85.9) |

| 106–162 | 14954 | 94.7 (94.4–95.1) | 50–99 | 8174 | 93.3 (92.8–93.9) |

| 163–227 | 15110 | 95.7 (95.4–96.0) | 100–149 | 11646 | 94.3 (93.9–94.8) |

| 228–326 | 14462 | 95.4 (95.1–95.8) | ≥ 150 | 47586 | 95.2 (95.0–95.4) |

| ≤327 | 13788 | 94.5 (94.1–94.9) | |||

| QI 6 Time interval of less than 7 days between diagnosis and operation | |||||

| ≤105 | 24072 | 15.6 (15.1–16.0) | <50 | 8785 | 21.0 (20.2–21.9) |

| 106–162 | 25544 | 10.9 (10.5–11.3) | 50–99 | 13817 | 12.7 (12.2–13.3) |

| 163–227 | 26062 | 8.4 (8.0–8.7) | 100–149 | 19734 | 11.9 (11.4–12.3) |

| 228–326 | 24784 | 8.0 (7.7–8.4) | ≥150 | 81002 | 7.3 (7.2–7.5) |

| ≥327 | 22876 | 5.2 (4.9–5.5) | |||

| QI 7 Time interval of more than 21 days between diagnosis and operation | |||||

| ≤105 | 24072 | 22.0 (21.5–22.6) | <50 | 8785 | 18.1 (17.3–18.9) |

| 106–162 | 25544 | 25.8 (25.3–26.3) | 50–99 | 13817 | 24.0 (23.3–24.7) |

| 163–227 | 26062 | 29.4 (28.8–29.9) | 100–149 | 19734 | 25.3 (24.7–25.9) |

| 228–326 | 24784 | 30.2 (29.6–30.8) | ≥ 150 | 81002 | 31.7 (31.4–32.0) |

| ≥327 | 22876 | 37.4 (36.8–38.0) | |||

Explanations: The quality indicators refer to baseline totals defined by indicator definitions. For this reason the population included in the calculations is not identical to the population used to categorize case numbers (cf Table 1). Indicators 3 and 4 have larger case numbers than the case number shown in Table 1 for DCIS, as not only patients having their first operation are included in calculating the indicators.

DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ; CI = confidence interval; QI = quality indicator

eTable. Subgroup analysis for quality indicators, differentiated by case number categories*.

| Category (quintile) | Number of patients | Mean (95% CI) | Category (case number groups) | Number of patients | Mean (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QI 1 Pretherapeutic histological confirmation of diagnosis | |||||

| ≤105 | 4160 | 97.7 (97.2 to 98.1) | <50 | 1223 | 96.7 (95.6 to 97.6) |

| 106 to 162 | 5294 | 98.5 (98.1 to 98.8) | 50 to 99 | 2607 | 98.0 (97.4 to 98.5) |

| 163 to 227 | 5924 | 98.4 (98.1 to 98.7) | 100 to 149 | 4115 | 98.6 (98.2 to 98.9) |

| 228 to 326 | 5669 | 98.6 (98.3 to 98.9) | ≥ 150 | 19043 | 98.6 (98.4 to 98.8) |

| ≥ 327 | 5941 | 98.9 (98.6 to 99.1) | |||

| QI 2 Intraoperative specimen radiography with sonographic wire marking | |||||

| ≤ 105 | 949 | 96.4 (95.0 to 97.4) | <50 | 234 | 91.0 (86.7 to 94.1) |

| 106 to 162 | 1437 | 98.7 (98.0 to 99.2) | 50 to 99 | 674 | 98.5 (97.3 to 99.2) |

| 163 to 227 | 1778 | 96.6 (95.7 to 97.4) | 100 to 149 | 1046 | 98.5 (97.5 to 99.1) |

| 228 to 326 | 1718 | 99.0 (98.3 to 99.3) | ≥ 150 | 6219 | 97.9 (97.5 to 98.2) |

| ≥ 327 | 2291 | 97.9 (97.3 to 98.5) | |||

| QI 3 Primary axillary dissection in DCIS | |||||

| ≤105 | 932 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.8) | <50 | 233 | 0.4 (0.1 to 2.4) |

| 106 to 162 | 1479 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.7) | 50 to 99 | 623 | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.9) |

| 163 to 227 | 1727 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.8) | 100 to 149 | 1134 | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.6) |

| 228 to 326 | 1748 | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.4) | ≥150 | 5531 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) |

| 327≥ | 1635 | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | |||

| QI 4 Lymph node biopsy in DCIS and breast conserving treatment | |||||

| ≤ 105 | 795 | 15.5 (13.1 to 18.2) | <50 | 188 | 17.0 (12.3 to 23.0) |

| 106 to 162 | 1270 | 12.7 (11.0 to 14.6) | 50 to 99 | 546 | 15.2 (12.4 to 18.5) |

| 163 to 227 | 1451 | 12.1 (10.5 to 13.8) | 100 to 149 | 969 | 12.9 (10.9 to 15.2) |

| 228 to 326 | 1417 | 12.1 (10.5 to 13.9) | ≥ 150 | 4541 | 11.6 (10.7 to 12.5) |

| ≥ 327 | 1311 | 10.2 (8.7 to 12.0) | |||

| QI 5 Indication for sentinel lymph node biopsy | |||||

| ≤ 105 | 4399 | 96.2 (95.6 to 96.7) | <50 | 1310 | 94.0 (92.6 to 95.2) |

| 106 to 162 | 5430 | 97.5 (97.1 to 97.9) | 50 to 99 | 2767 | 97.2 (96.5 to 97.7) |

| 163 to 227 | 5977 | 97.9 (97.5 to 98.2) | 100 to 149 | 4178 | 97.4 (96.9 to 97.9) |

| 228 to 326 | 5741 | 97.6 (97.2 to 98.0) | ≥ 150 | 19051 | 97.3 (97.1 to 97.5) |

| ≥ 327 | 5759 | 96.4 (95.9 to 96.8) | |||

| QI 6 Time interval of less than 7 days between diagnosis and operation | |||||

| ≤ 105 | 3543 | 12.6 (11.6 to 13.8) | <50 | 1036 | 19.6 (17.3 to 22.1) |

| 106 to 162 | 4498 | 9.4 (8.6 to 10.3) | 50 to 99 | 2240 | 10.0 (8.8 to 11.3) |

| 163 to 227 | 4935 | 7.6 (6.9 to 8.4) | 100 to 149 | 3502 | 10.4 (9.4 to 11.4) |

| 228 to 326 | 4573 | 7.0 (6.3 to 7.8) | ≥ 150 | 15335 | 6.2 (5.8 to 6.6) |

| ≥ 327 | 4564 | 3.8 (3.3 to 4.4) | |||

| QI 7 Time interval of more than 21 days between diagnosis and operation | |||||

| ≤ 105 | 3543 | 20.3 (19.0 to 21.7) | <50 | 1036 | 17.0 (14.8 to 19.4) |

| 106 to 162 | 4498 | 23.3 (22.1 to 24.6) | 50 to 99 | 2240 | 21.4 (19.8 to 23.2) |

| 163 to 227 | 4935 | 27.2 (26.0 to 28.5) | 100 to 149 | 3502 | 23.0 (21.6 to 24.4) |

| 228 to 326 | 4573 | 28.3 (27.0 to 29.6) | ≥ 150 | 15335 | 30.0 (29.3 to 30.7) |

| ≥ 327 | 4564 | 36.2 (34.8 to 37.6) | |||

*Subgroup 1 for indicators 1, 2, and 5 to 7: Patients younger than 65 years, with ASA 1 or ASA 2, node status pN0, ypN0, and tumor size pT0, ypT0, or pT1, ypT1

Subgroup 2 for indicators 3 and 4: Patients younger than 65 with ASA 1 or ASA 2 and tumor size <5 cm.

Explanations: the quality indicators refer to baseline totals that were set by means of the indicator definition. For this reason, the population in the calculations is not identical with the population used to categorize case numbers (cf Table 1). Indicators 3 and 4 have larger case numbers than the case number for DCIS shown in Table 1, as not only patients with first operations were included in calculating the indicators. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ; C = confidence interval; QI = quality indicator

In the subgroup analysis, the volume effects between hospitals with smaller case numbers and hospitals with larger case numbers are not as clear as in the overall analysis (eTable).

For indicators 6 and 7, for the time interval between diagnosis and operation, the results of the overall analysis and those of the subgroup analysis indicate a continuous association: hospitals with smaller case numbers operate comparatively more patients within 7 days and hospitals with larger case numbers operate comparatively more patients later than 21 days after the diagnosis.

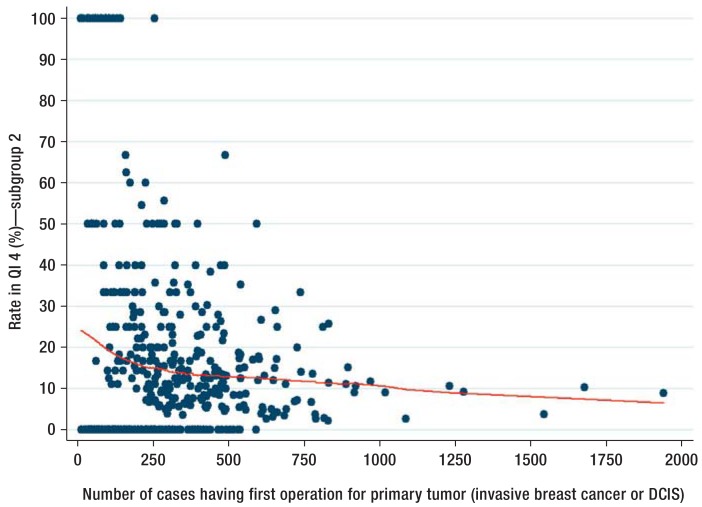

The observed volume effects are shown as examples in Figure 1 for indicator 5, “indication for sentinel lymph node biopsy” and in Figure 2 for indicator 4, “lymph node removal in DCIS and breast conserving treatment.” The indicator result is visualized as a dot per hospital. Additionally, results from the Lowess regression are shown. The steady rise or fall in the curve shows a positive association between the numbers of cases treated in an institution and the result achieved by that institution.

Figure 1.

QI 5 “Indication for sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB)“

The quality indicator 5 was calculated on the basis of the patient population without restrictions. The result for the indicator is shown as a scatter plot. Each hospital is visualized as a blue dot. The red curve represents a non-parametric regression, which can show up non-linear associations and is based on locally weighted smoothing algorithms (Lowess regression; [30]). The x axis shows the number of inpatient cases and the y axis the indicator result. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ

Figure 2.

QI 4 “Lymph node biopsy in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and breast conserving therapy”

The indicator was calculated on the basis of subgroup 2, which includes patients younger than 65 years with ASA1 or ASA2 and a total tumor size <5 cm. The result for the indicator is shown as a scatter plot. Each hospital is visualized as a blue dot. The red curve represents a non-parametric regression, which can show up non-linear associations and is based on locally weighted smoothing algorithms (Lowess regression; [30]). The x axis shows the number of inpatient cases and the y axis shows the indicator result. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ

Discussion

Overall the results indicate a better quality of care in hospitals dealing with larger case numbers. Six of the seven process indicators show more favorable profiles for hospitals with larger case numbers than for hospitals with smaller case numbers. However, these associations are not consistently steady: the worst result is mostly seen in the lowest case number category. This result is confirmed, albeit in a less pronounced way, by the subgroup analyses. Restricting patients by classifying them into two subgroups has yielded a homogeneous, healthier patient population, so that it may be assumed for these analyses that the observed results in smaller hospitals cannot be explained with sicker patients or patients with more advanced breast cancer. Since the indicators in the service sector breast cancer without exception describe processes that should be applied in the same manner at least to all patients in the subgroup, further risk adjustment was not required.

Lacking structural requirements—for example, in the provision of a multidisciplinary team or technical equipment—provide a further reason for the identified differences in quality (5, 19, 20, 31). The structured dialogue—a process in which the causes of indicator results that have thrown up mathematical abnormalities are analyzed in a dialogue with the respective hospitals—confirmed that pretherapeutic confirmation of the diagnosis or sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) could not be adequately undertaken in some hospitals with smaller case numbers owing to lacking technical equipment or cooperation (32). Furthermore, there are indications that guideline recommendations and their changes penetrate more slowly to hospitals with smaller case numbers, and, therefore, guideline adherence is poorer in such hospitals than in those with comparatively larger case numbers. Individual authors have confirmed that the reasons of why hospitals with large case numbers offer a higher quality of care—in the shape of longer long-term survival—include better knowledge and awareness of current research results (31). Furthermore, there are indications that better adherence to guidelines is associated with improved recurrence-free survival and total survival in breast cancer (33, 34).

Regarding the observed volume effects, indicator 7, “Time interval of more than 21 days between diagnosis and operation,” constitutes an exception. In hospitals with larger case numbers, this indicator shows longer waiting times before surgery. This is important, less in terms of the prognosis, but in terms of the possible psychological burden on the patients. Selection effects are a possible reason for longer waiting times. Patients in the mammography screening program are mostly referred to certified breast centers for treatment. Because of the structural divide between outpatient screening diagnostics by radiologists in private practice and the service provided under inpatient conditions in hospital, such patients are probably admitted to hospital with a notable delay after histological confirmation of the diagnosis. On the other hand, the significantly reduced time interval between diagnosis and operation (QI 6) in hospitals with smaller case numbers supports the assumption that the time taken up by the preoperative diagnostic evaluation or explanations of alternative treatment options is much shorter because of the lacking structures or because of a more limited range of treatments, and patients therefore undergo surgery earlier than in other centers. A shorter waiting time before surgery also limits opportunities for seeking out a second opinion.

Longer intervals between histological confirmation of the diagnosis and the start of treatment may also be seen as an indication that, on the one hand, larger centers’ treatment capacities are exhausted. On the other hand, they may mean that in Germany, the formation of breast centers with a view to their possible treatment capacity has not reached completion.

Regarding the two indicators relating to the time interval between diagnosis and operation (QI 6 and QI 7), the question remains unanswered whether these represent a straightforward quality deficit, since the optimal time interval between diagnosis and surgery is currently not defined in the S3 guideline (2).

Our study is subject to several limitations. The studied association between case numbers and health care quality in breast cancer surgery relates to process indicators. The study of longer-term result parameters would be of additional interest—for example, mortality and morbidity after breast surgery (19)—or shorter-term result parameters—for example, secondary resection rates. The structure of the present data does not allow for such an approach, however, because follow-up data are currently not being collected. Furthermore, it may take years for local recurrences or metastases to manifest in patients with breast cancer (19), or mortality data are available for a population that is otherwise mostly healthy (12, 14). For these reasons we focused on process indicators that test guideline recommendations for the diagnostic evaluation and primary therapy.

In contrast to some other studies with a similar research question (12, 18), the rate of breast conserving treatments was not included as a quality indicator in the analysis. In our view, further parameters would need to be included in the consideration in order to assess the indication for breast conserving treatment, which are not part of the present data. For this reason, the indicator for breast conserving surgery has not been included in the esQS since 2013 (26).

Investigating the association between volume and care quality is subject to various problems. In principle, we can only point at an association between case numbers and care quality; we cannot prove a direct causal association (12). The results of our study confirm the discussion in the international literature, according to which the extent of the association and the direction of causality between rates of surgical procedures and treatment outcome are not always clear. Results may, for example, depend on the procedure under analysis and the selected threshold, and may vary strongly (4– 6, 23). In our view, the empirical deduction of the threshold is not convincingly possible on the basis of the available data; for this reason, we did not calculate such a value. Instead, different categorizations of case numbers of breast cancer patients were juxtaposed, in order to, if possible, circumvent the disadvantage of an arbitrary definition of case number categories. We did not differentiate any further, to keep our results comprehensible and clear.

Further evaluations would be of interest, differentiated by certified and non-certified breast centers. Such differentiation cannot be undertaken on the basis of our dataset, as we only had pseudonyms for the hospitals. Furthermore, the results can be allocated only to an institution, not an individual surgeon or team of surgeons.

In sum, volume effects exist in breast surgery in the area of process quality, which vary by the included patient population and threshold value. In particular, hospitals with fewer than 50 cases or 106 patients per year offer a poorer quality of care. At the national level, the quality of care therefore seems to be anything but consistently high. In order to further study and improve guideline adherence, nationwide quality assurance seems to be indicated even outside specialized oncological centers, which would then penetrate to hospitals with smaller case numbers.

Key Messages.

International studies have shown volume effects for several surgical procedures.

For the first time, such volume effects were investigated on the basis of process indicators and inpatient data from Germany.

Hospitals with larger case numbers show a more favorable process quality profile.

The results in hospitals with large case numbers indicate better guideline adherence.

Quality improvements should be aimed for by means of continuous quality assurance.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Robert Koch-Institut (RKI) Ausgabe. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut; 2013. Krebs in Deutschland 2009/2010, 9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.AWMF, DKG DKH. Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe. 2012. Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie für die Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms. Langversion 3.0, Aktualisierung 2012. Senologie - Zeitschrift für Mammadiagnostik und -therapie. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:1364–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197912203012503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo RN, Chung KP, Lai MS. Re-examining the significance of surgical volume to breast cancer survival and recurrence versus process quality of care in Taiwan. Health Serv Res. 2013;48:26–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthias K, Gruber S, Pietsch B. Evidenz von Volume-Outcome-Beziehungen und Mindestmengen: Diskussion in der aktuellen Literatur. Gesundheits- und Sozialpolitik. 2014;68:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:511–520. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heller G, Günster C, Misselwitz B, Feller A, Schmidt S. Jährliche Fallzahl pro Klinik und Überlebensrate sehr untergewichtiger Frühgeborener (VLBW) in Deutschland - Eine bundesweite Analyse mit Routinedaten. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2007;211:123–131. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-960747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heller G, Richardson DK, Schnell R, Misselwitz B, Kunzel W, Schmidt S. Are we regionalized enough? Early-neonatal deaths in low-risk births by the size of delivery units in Hesse, Germany 1990-1999. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1061–1068. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siesling S, Tjan-Heijnen VC, de Roos M, et al. Impact of hospital volume on breast cancer outcome: a population-based study in the Netherlands. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147:177–184. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Sparapani RA, Zhang X, Neuner JM, Gilligan MA. Exploring the surgeon volume outcome relationship among women with breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1958–1963. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDermott AM, Wall DM, Waters PS, et al. Surgeon and breast unit volume-outcome relationships in breast cancer surgery and treatment. Ann Surg. 2013;258:808–813. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a66eb0. discussion 13-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gooiker GA, van Gijn W, Post PN van de Velde, CJ Tollenaar RA, Wouters MW. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the volume-outcome relationship in the surgical treatment of breast cancer. Are breast cancer patients better of with a high volume provider? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36(Suppl 1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guller U, Safford S, Pietrobon R, Heberer M, Oertli D, Jain NB. High hospital volume is associated with better outcomes for breast cancer surgery: analysis of 233,247 patients. World J Surg. 2005;29:994–999. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7831-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roohan PJ, Bickell NA, Baptiste MS, Therriault GD, Ferrara EP, Siu AL. Hospital volume differences and five-year survival from breast cancer. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:454–457. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.3.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peltoniemi P, Peltola M, Hakulinen T, Hakkinen U, Pylkkanen L, Holli K. The effect of hospital volume on the outcome of breast cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1684–1690. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peltoniemi P, Huhtala H, Holli K, Pylkkanen L. Effect of surgeon’s caseload on the quality of surgery and breast cancer recurrence. Breast. 2012;21:539–543. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vrijens F, Stordeur S, Beirens K, Devriese S, van Eycken E, Vlayen J. Effect of hospital volume on processes of care and 5-year survival after breast cancer: a population-based study on 25000 women. Breast. 2012;21:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallwiener M, Brucker SY, Wallwiener D, Steering C. Multidisciplinary breast centres in Germany: a review and update of quality assurance through benchmarking and certification. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:1671–1683. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2212-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kowalski C, Ferencz J, Brucker SY, Kreienberg R, Wesselmann S. Quality of care in breast cancer centers: results of benchmarking by the German Cancer Society and German Society for Breast Diseases. Breast. 2015;24:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson AR, Marotti L, Bianchi S, et al. The requirements of a specialist Breast Centre. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3579–3587. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DKG/DGS. Erhebungsbogen für Brustkrebszentren (Stand: 01.09.2014) www.senologie.org/brustzentren/zertififzierungsrichtlinien. (last accessed on 15 June 2015)

- 23.Com-Ruelle L, Or Z, Renaud T. The volume-outcome relationship in hospitals. Issues in Health Economics. 2008;135:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.BQS. BQS-Qualitätsreport 2002. Düsseldorf: Bundesgeschäftsstelle Qualitätssicherung gGmbH; 2003. Qualität sichtbar machen. [Google Scholar]

- 25.AQUA. Göttingen: AQUA - Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im Gesundheitswesen; 2015. Beschreibung der Qualitätsindikatoren für das Erfassungsjahr 2014 Mammachirurgie. [Google Scholar]

- 26.AQUA. Göttingen: AQUA - Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im Gesundheitswesen; 2014. Beschreibung der Qualitätsindikatoren für das Erfassungsjahr 2013 Mammachirurgie. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson E. Probable Inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. JASA. 1927;22:209–212. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17:857–872. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleveland WS. Robust Locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. JASA. 1979;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ. Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis by local fitting. JASA. 1988;83:596–610. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scharl A, Gohring UJ. Does center volume correlate with survival from breast cancer? Breast Care (Basel) 2009;4:237–244. doi: 10.1159/000229531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AQUA. Berichte zum Strukturierten Dialog. www.sqg.de/ergebnisse/strukturierter-dialog/berichte-strukturierter-dialog/index.html. (last accessed on 15 June 2015)

- 33.Wöckel A, Varga D, Atassi Z, et al. Impact of guideline conformity on breast cancer therapy: results of a 13-year retrospective cohort study. Onkologie. 2010;33:21–28. doi: 10.1159/000264617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varga D, Wischnewsky M, Atassi Z, et al. Does guideline-adherent therapy improve the outcome for early-onset breast cancer patients? Oncology. 2010;78:189–195. doi: 10.1159/000313698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]