Abstract

Objectives

Syphilis is endemic among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women in Latin America. The objective of this study was to assess if those who screen positive for syphilis are receiving appropriate care and treatment.

Methods

We use data from the 2011 Peruvian National HIV Sentinel Surveillance to describe the syphilis care cascade among high-risk MSM and transgender women. Medical records from participants who had a positive syphilis screening test at two of the enrolment sites in Lima were reviewed to determine their subsequent course of care.

Results

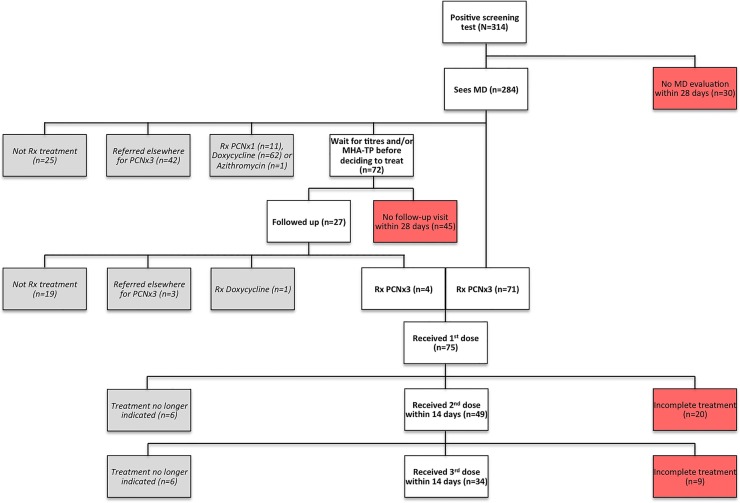

We identified a cohort of 314 syphilis seropositive participants (median age: 30, 33.7% self-identified as transgender). Only 284/314 (90.4%) participants saw a physician for evaluation within 28 days of their positive test. Of these, 72/284 (25.4%) were asked to return for confirmatory results before deciding whether or not to start treatment; however, 45/72 (62.5%) of these participants did not follow up within 28 days. Of the people prescribed three weekly doses of penicillin, 34/63 (54%) received all three doses on time.

Conclusions

Many MSM and transgender women with a positive syphilis screening test are lost at various steps along the syphilis care cascade and may have persistent infection. Interventions in this population are needed to increase testing, link seropositive patients into care and ensure that they receive appropriate and timely treatment.

Keywords: INFECTIOUS DISEASES, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study focused on treatment management of a population with a high prevalence of syphilis in a resource-limited setting.

The relatively small sample size for our primary outcome limited the ability to assess for factors associated with completion of treatment on time.

However, our data illustrate where Peruvian men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women who screen positive for syphilis are lost to follow-up at various steps in management.

Knowledge of these issues can help make informed operational changes—at least at the local level—to improve treatment coverage and reduce spread of syphilis for MSM and transgender women in Peru.

Introduction

Syphilis is a public health concern that disproportionately affects men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TW) throughout Peru and Latin America.1 The WHO estimates that the prevalence of syphilis among the general population of men in the Americas is 1.5%,2 but as many as 28.9% of MSM in Peru have been found to be seropositive for syphilis.1 3 One recent study examined TW separately, estimating the prevalence of rapid plasma reagin (RPR)-positive Peruvian TW at 22.9%.4

Even though treatment for syphilis exists, the complex management of individuals who screen positive for this disease may hinder efforts to control the concentrated epidemic. In combination with clinical history and examination, confirmatory testing and quantitative titres are often needed to properly prescribe treatment; completion of scheduled doses and post-treatment serological follow-up are also crucial.5 Adherence to these guidelines can be difficult, particularly when multiple appointments are needed for three weekly injections of Benzathine penicillin G, the preferred treatment regimen for late syphilis.5 6 For instance, in South Africa, where local guidelines recommend three weekly doses of penicillin for maternal syphilis, as few as 41% of pregnant women received the full course of treatment.7–9

A syphilis cascade of care exists, similar to what has been described in the management of HIV.10 For HIV, while the ultimate goal of care is to achieve an undetectable viral load, patients are lost at various steps in their management. These steps include diagnosis, linkage-to-care, retention-in-care, initiation of antiretroviral therapy and adherence to treatment, ultimately leading to viral suppression for only 25% of HIV-infected individuals in the USA,10 with similar challenges described in low-income and middle-income countries.11 While comparable in many ways, the syphilis care cascade has notable differences, including that syphilis is curable, a positive screening test may be from a previously treated infection and that the duration of treatment depends on the stage of the disease.

To the best of our knowledge, no published information exists on the proportion of MSM and TW who complete treatment for syphilis in a developing country like Peru. While extensive data exist in South Africa on pregnant women, adherence in MSM and TW is likely to differ. In a low-resource setting where there are subpopulations with a high prevalence of syphilis and reinfection,12 describing the care cascade will allow us to identify and target gaps and barriers in management to reduce both the incidence and prevalence of syphilis in this population. Since syphilis can also increase the risk of both HIV transmission and acquisition,6 13 reducing the burden of this disease may also improve the control of the HIV epidemic among MSM and TW in Latin America.14 15 Therefore, this study aimed to describe the syphilis care cascade among MSM and TW screening positive for syphilis in Peru.

Methods

Study participants

From 22 June to 2 November 2011, 5576 behaviourally high-risk MSM and TW were recruited from five major cities in Peru for the 2011 National HIV Sentinel Surveillance. Participants were eligible if they were ≥18 years old, born biologically male and reported sex with a male (or a male-to-female transgender) partner during the past year. Detailed descriptions of the Sentinel Surveillance and its participants have been reported previously.16 17

For the current study, we analysed a subset of participants from the Sentinel Surveillance who had a positive RPR at a non-governmental research organisation (NGO) and clinic that conducts HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STI) research at two sites in Lima, Peru.

Study procedures

As part of the Sentinel Surveillance, participants received a syphilis-screening test using either qualitative RPR (Organon Teknika, Durham, North Carolina, USA) or Bioline Syphilis 3.0 (Standard Diagnostic Inc, Korea) with positive results quantified and confirmed using RPR and microhaemagglutination assay for Treponema pallidum antibodies (MHA-TP) (Organon Teknika, Durham, North Carolina, USA), respectively. In addition, participants received an HIV-1/2 Rapid Antibody Test (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott, Illinois, USA) with all positive results confirmed by western blot (Biorad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA). Participants also completed a demographic and behavioural survey using Computer-Assisted Self-Interview. Prior to beginning any procedures, each participant gave informed consent.

We performed a retrospective chart review for the subset of participants who had a positive RPR or Bioline screening test as a part of the Sentinel Surveillance at the specific NGO. For all positively screened participants, we reviewed their available medical and treatment records following the positive screening test to determine their course of care along the syphilis care cascade. After a positive screening test, the steps and definitions of our cascade included: consulting a physician for a medical evaluation; returning for results of RPR titres and/or MHA-TP to decide about treatment (within 28 days), if applicable; being prescribed treatment, if appropriate; and receiving treatment as indicated (ie, for late latent syphilis, receiving three weekly shots of penicillin). We considered participants to have seen a physician if a medical evaluation was recorded in their chart within 28 days of their positive screening test. If a participant saw a physician and a decision about treatment was delayed to wait for RPR titres or MHA-TP results, participants must have returned within 28 days to be considered having followed up. For participants who were prescribed three weekly doses of penicillin, only treatment that was started at the NGO within 28 days was considered eligible in the analysis of our main outcome. We considered the second and third doses of penicillin to be completed ‘on time’ if they were administered within 14 days of the previous dose, as pharmacokinetics suggest that up to 2-week intervals between doses may be sufficient before restarting treatment.5

Statistical analysis

Data from patients’ medical records were recorded into an electronic database. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software V.12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to characterise our participant profile. We illustrated the syphilis care cascade using a flow chart for the study population. Our main outcome was receiving all three doses of penicillin on time, which was treated as a dichotomous variable. To determine characteristics associated with this primary outcome of interest, we created contingency tables using the following predetermined predictor variables: age, level of education, sexual orientation, gender identity, self-identification as a sex worker, condom use, alcohol use (using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) screening tool18), drug use, history of syphilis, RPR titre and HIV test result. We used a Poisson regression with estimation of robust variances in order to estimate prevalence ratios along with 95% CIs. In comparison to the more commonly used logistic regression approach, this method of analysis provides a less biased and more conservative estimate of magnitude of the association between variables, especially when the prevalence of the outcome is higher than 10%.19 Variables were considered statistically significant if p<0.05.

Results

Demographic, sociobehavioural and clinical characteristics

Of the 1569 participants recruited for the 2011 Sentinel Surveillance at the NGO enrolment sites, we identified 314 (20%) with a positive syphilis screening test. For these 314 participants, the median age was 30, and most were high school graduates (54.2%). The majority (80.9%) were identified as homosexual and a third (33.7%) identified as transgender. Further demographic and behavioural factors for the participants who met the criteria for our study are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, sociobehavioural and clinical characteristics of participants (N=314)

| Characteristic | Total | HIV-positive | HIV-negative | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=314 | N=97 | N=217 | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age, years | 0.040 | |||

| ≥30 | 161 (51.9) | 41 (43.2) | 120 (55.8) | |

| <30 | 149 (48.1) | 54 (56.8) | 95 (44.2) | |

| Level of education | 0.708 | |||

| High school graduate | 168 (54.2) | 53 (55.8) | 115 (53.5) | |

| Less than high school graduate | 142 (45.8) | 42 (44.2) | 100 (46.5) | |

| Sexual orientation (self-identified) | 0.449 | |||

| Heterosexual | 8 (2.6) | 3 (3.2) | 5 (2.3) | |

| Bisexual | 51 (16.5) | 12 (12.6) | 39 (18.2) | |

| Homosexual | 250 (80.9) | 80 (84.2) | 170 (79.4) | |

| Trans identity (self-identified) | 0.294 | |||

| Yes | 104 (33.7) | 36 (37.9) | 68 (31.8) | |

| No | 205 (66.3) | 59 (62.1) | 146 (68.2) | |

| Sex-worker (self-identified) | 0.363 | |||

| Yes | 129 (41.9) | 43 (45.7) | 86 (40.2) | |

| No | 179 (58.1) | 51 (54.3) | 128 (59.8) | |

| Condom use in last sexual encounter | 0.484 | |||

| Yes | 171 (55.5) | 55 (58.5) | 116 (54.2) | |

| No | 137 (44.5) | 39 (41.5) | 98 (45.8) | |

| Presence of Alcohol Use Disorder (AUDIT score ≥8) | 0.930 | |||

| Yes | 182 (61.5) | 55 (61.1) | 127 (61.7) | |

| No | 114 (38.5) | 35 (38.9) | 79 (38.4) | |

| Drug use in the past 3 months | 0.207 | |||

| Yes | 57 (19.2) | 21 (23.6) | 36 (17.3) | |

| No | 240 (80.8) | 68 (76.4) | 172 (82.7) | |

| Syphilis in the past year (self-reported) | 0.005 | |||

| Yes | 66 (21.4) | 11 (11.6) | 55 (25.7) | |

| No | 243 (78.6) | 84 (88.4) | 159 (74.3) | |

| Syphilis titre | <0.001 | |||

| >1:8 | 137 (43.6) | 59 (60.8) | 78 (35.9) | |

| ≤1:8 | 177 (56.4) | 38 (39.2) | 139 (64.1) | |

Data are number (%) of participants with characteristics.

Clinically, a slight majority (56.4%) had a syphilis titre ≤1:8. Almost a third (30.9%) of the participants in our study had a positive HIV test confirmed by western blot. Those who were HIV-positive were more likely to be <30 years old (p=0.040), report no history of syphilis in the past year (p=0.005) and have a RPR titre >1:8 (p<0.001).

Course of care following a positive syphilis screening test

We tracked the course of care for the 314 participants included in our analysis (figure 1). Of the 284/314 (90.4%) participants who saw a physician for a medical evaluation within 28 days, 187/284 (65.8%) were prescribed antibiotic treatment at the same visit, of whom 113/187 (60.4%) were prescribed three weekly doses of penicillin (versus a single dose of penicillin or treatment with an alternative antibiotic). There were 72/284 (25.4%) participants who were asked to return for confirmatory results before deciding whether or not to start treatment, but only 27/72 (37.5%) returned within 28 days. Of the participants who returned and received the results of their confirmatory tests, 8/27 (29.6%) were prescribed either doxycycline or three doses of penicillin for the treatment of syphilis; the rest were not prescribed treatment.

Figure 1.

Course of care following positive syphilis screening test among 314 participants recruited at two non-governmental organization clinics in Lima, Peru through the 2011 HIV National Sentinel Surveillance. Rx=prescribed, PCN=penicillin, x1=one dose, x3=three weekly doses.

On-time completion of three weekly doses of penicillin

Although in total 120/314 (38.2%) participants were prescribed three weekly doses of penicillin, 45 were referred for treatment elsewhere and we were only able to assess completion of treatment for 75/120 (62.5%) participants. In addition, there were 12/75 (16%) participants who received one or two injections of penicillin at one of the two enrolment sites before quantitative RPR titres were available that led the physician to decide to discontinue treatment. Of the remaining participants, 43/63 (68.3%) received their second dose of penicillin within 14 days of their first dose and 34/63 (54%) received their third dose of penicillin within 14 days of their second dose.

In bivariate analysis, no factor was associated with completion of three weekly doses of penicillin on time (table 2).

Table 2.

Association between predictor variables with completion of treatment on time for those prescribed three weekly doses of penicillin (N=63)

| Predictor variable | Completed treatment on time N (%) | Did NOT Complete treatment on time N (%) | PR (95%CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 34 (54.0) | 29 (46.0) | ||

| Age, years | 0.390 | |||

| ≥30 | 19 (59.4) | 13 (40.6) | 1.22 (0.77 to 1.96) | |

| <30 | 15 (48.4) | 16 (51.6) | Ref | |

| Level of education | 0.156 | |||

| High school graduate | 24 (61.5) | 15 (38.5) | 1.48 (0.86 to 2.53) | |

| <High school graduate | 10 (41.7) | 14 (58.3) | Ref | |

| Sexual orientation (self-identified) | 0.831 | |||

| Heterosexual/bisexual | 9 (56.3) | 7 (43.8) | 1.06 (0.63 to 1.77) | |

| Homosexual | 25 (53.2) | 22 (46.8) | Ref | |

| Trans identity (self-identified) | 0.134 | |||

| Yes | 11 (68.8) | 5 (31.3) | 1.40 (0.90 to 2.19) | |

| No | 23 (48.9) | 24 (51.1) | Ref | |

| Sex-worker (self-identified) | 0.757 | |||

| Yes | 13 (56.5) | 10 (43.5) | 1.08 (0.67 to 1.72) | |

| No | 21 (52.5) | 19 (47.5) | Ref | |

| Condom use in last sexual encounter | 0.892 | |||

| Yes | 17 (53.1) | 15 (46.9) | 0.97 (0.61 to 1.53) | |

| No | 17 (54.8) | 14 (45.2) | Ref | |

| Presence of Alcohol Use Disorder (AUDIT score ≥8) | 0.206 | |||

| Yes | 19 (63.3) | 11 (36.7) | 1.36 (0.85 to 2.18) | |

| No | 14 (46.7) | 16 (53.3) | Ref | |

| Drug use in the past 3 months | 0.576 | |||

| Yes | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.16 (0.69 to 1.93) | |

| No | 25 (53.2) | 22 (46.8) | Ref | |

| Syphilis in the past year (self-reported) | 0.395 | |||

| Yes | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | 0.73 (0.36 to 1.50) | |

| No | 29 (56.9) | 22 (43.1) | Ref | |

| Syphilis titre | 0.496 | |||

| >1:8 | 17 (50.0) | 17 (50.0) | 0.85 (0.54 to 1.35) | |

| ≤1:8 | 17 (58.6) | 12 (41.4) | Ref | |

| HIV status | 0.980 | |||

| Positive | 13 (54.2) | 11 (45.8) | 1.01 (0.63 to 1.61) | |

| Negative | 21 (53.9) | 18 (46.2) | Ref | |

Participants lost to follow-up

A significant number of participants were lost to follow-up before a physician could make a decision about whether or not treatment should be prescribed. There were 30/314 (9.6%) participants who did not see a physician for medical evaluation after their positive screening test. This group of participants was more likely than those who did see a physician to have a titre ≤1:8 (80% vs 53.9%, p=0.006), self-identify as trans (60.7% vs 31%, p=0.001) and self-identify as a sex worker (67.9% vs 31%, p=0.003). There was also a trend for this group of people who skipped medical evaluation to have reported syphilis in the past year compared to those who saw a physician (35.7% vs 19.9%, p=0.052).

There were 72/284 (25.4%) participants who were asked to return for confirmatory results before deciding whether or not to start treatment; however, 45/72 (62.5%) of these participants did not follow up with their results within 28 days. Those who also screened positive on the HIV rapid antibody test at the initial visit were more likely to return for confirmatory results compared to those who screened HIV-negative on the rapid antibody test (62.5% vs 32.2%, p=0.048); no other predictor variable was associated with follow-up of confirmatory results. Of the people who did not return for a follow-up visit after being asked to return for confirmatory results, 31/45 (68.9%) were subsequently found to have a titre ≤1:8.

A total of 104/314 (33.1%) participants were non-adherent and lost at any point along the care cascade (did not see a physician within 28 days, did not follow up with confirmatory results or did not complete three doses of weekly penicillin on time). We compared participant demographics to this outcome and only trans identity (versus non-trans identity) was associated with being more likely to be lost in the syphilis care cascade (41.4% vs 28.3%, p=0.021).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyse the course of care and treatment of MSM and TW who screen positive for syphilis in Latin America. Our data illustrate that a large number of people with a positive screening test are lost at various steps along the syphilis care cascade.

For participants who were prescribed and needed three doses of weekly penicillin, adherence to the treatment regimen was low, with only 54% completing all three doses on time. These data suggest that almost half of the MSM and TW prescribed this treatment may still have persistent infection, permitting their disease to progress to later stages and cause more serious neurological and cardiovascular sequelae.20 Although our criteria for completing treatment were stricter because it incorporated a time limit between doses, our population had similar rates of completion for the three-dose weekly regimen as pregnant women in South Africa with syphilis.7–9 However, adherence in our study among MSM and TW in Peru was much worse compared to a small audit study among mostly homosexual/bisexual self-identified men in the UK, where 90% completed their treatment following any antibiotic regimen.21 Even though that study included adherence to all forms of treatment for syphilis (ie, fewer than three doses of penicillin and regimens that used doxycycline), the higher resources in the UK most likely contributed to more patients completing treatment there versus in either South Africa or Peru.

In addition to the low adherence to the weekly penicillin regimen, there was a significant number of participants who did not see a doctor after their positive result and a substantial number who did not follow up on their confirmatory results to determine whether or not they needed treatment. It is possible that many of these patients required treatment of some form, but were not fully assessed by a physician who could make an informed decision, and they too could be incompletely treated and could infect future sexual partners. Our study found that 80% of those who did not see a physician in a timely manner and more than two-thirds of those who did not follow up with confirmatory results to determine if they needed treatment had a titre of ≤1:8. While lower titres can be suggestive of either late infection22 or a serofast state23 (and are thus less likely to infect others22), a significant minority had titres >1:8 and were most likely highly infectious and needed treatment. Given the high prevalence of syphilis in this population, there is potential for a large number of cases of untreated infection.

Overall, a third of MSM and TW in our study were lost to follow-up at some point of the cascade and did not receive appropriate care as recommended by the clinics and physicians in the Sentinel Surveillance. Furthermore, TW appear to be at increased risk of being lost to follow-up in the syphilis care cascade, consistent with other studies which have found that HIV-positive TW are less likely to adhere to antiretrovirals than others for various reasons, including negative experiences and stigma with the healthcare system, prioritisation of hormone therapy and housing instability.24 25 On the other hand, initially screening positive for HIV on the rapid antibody test was associated with returning for a follow-up visit, as these people were more likely concerned about having HIV and also were most likely counselled by both healthcare providers and counsellors about the importance of returning and potentially starting treatment.

We acknowledge that our study contains limitations that restrict the generalisability of our findings. Since we recruited participants from two NGO clinics as part of a large sentinel surveillance study, our findings may demonstrate lower rates of adherence that would be observed in primarily clinical settings when the main purpose of the visit is clinical versus investigational. Second, a large portion of participants who required treatment were excluded from our primary outcome (completion of three doses of penicillin ‘on time’), either because they were prescribed oral medication or were referred elsewhere to receive penicillin treatment, and we were not able to assess their adherence. Related to this limitation is that we had a relatively small sample size, and may have found more factors associated with higher adherence if our study had more power. Given the small sample size, we did not conduct any multivariable analysis. Despite these limitations, our study documents the low frequency of treatment adherence and illustrates where many individuals who screen positive for syphilis may be lost. Knowledge of these issues can help make informed operational changes—at least at the local level—to improve treatment coverage for MSM and TW with syphilis infection.

Our study describes the syphilis care cascade among MSM and TW in Peru, which has important similarities to the HIV care cascade described previously,10 including among transgender women in the USA.24 However, the syphilis care cascade is complicated by the fact that a positive screening test may be from a previously treated infection, and thus may not automatically lead to the next step in the care cascade. Several decision points are needed that can exclude individuals from assessment further down the cascade, which makes the syphilis care cascade more complex than the HIV care cascade.

The ‘leaks’ in the syphilis care cascade call for strategies to improve follow-up and treatment adherence to address the high prevalence of syphilis in this population. Use of point-of-care testing among pregnant women in Peru has dramatically increased screening and treatment coverage for syphilis, with 80% of women who screen positive receiving at least two doses of penicillin.26 Presumptively treating all patients with a positive screening test may be an alternative to waiting for confirmatory results, since more than 6 of 10 participants who were asked to follow up did not. Another potential way to improve adherence includes reminders through text messages, which have been used as a cheap and efficient way for sexual health interventions,27 and MSM in Peru have found one such intervention to be acceptable.28 Finally, our data suggest that TW are at higher risk of being lost in the syphilis care cascade. Qualitative research focused on patient perspectives, as was carried out previously for the HIV care cascade,29 would be useful to understand why these individuals ‘drop out’ of the syphilis cascade of care.

While not addressed in this study, improving screening uptake would identify more people who need to be treated and would theoretically help to curtail the syphilis epidemic in this high-risk population. Certain strategies employed and found to be effective in Peru are pharmacy-based interventions such as the training of pharmacists to diagnose and treat STI,30 using a mobile outreach team to reach female sex workers30 31 and using the Internet to reach MSM for HIV and syphilis testing.32

Our study provides evidence that the multistep management of MSM and TW screening positive for syphilis is complex, leading to gaps in which people do not receive appropriate care along the way. Since syphilis continues to be highly prevalent among MSM and TW in Peru, an important public health goal is to determine ways to increase testing, link patients who test positive into care and ensure that they receive appropriate and timely treatment. This study begins to address where we should focus our efforts regarding the syphilis endemic in Peru.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants and staff at IMPACTA with whom this study was made possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: ECT designed the study, performed the chart review, conducted the statistical analyses, analysed the data, as well as drafted and revised the paper. ERS assisted in designing the study and in statistical analysis, mentored the first author, analysed the data and revised the draft paper. JLC and JRL assisted in designing the study, analysed the data, mentored the first author and revised the draft paper. JS approved the study design, provided access to the data and revised the draft paper.

Funding: ECT was supported by the South American Program in HIV Prevention Research (SAPHIR) grant number NIH R25 MH087222. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria grants PER-506-G03-H and PER-607-G05-H awarded to CARE PERU funded the 2011 Sentinel Surveillance.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Asociación Civil Impacta Salud y Educación (IMPACTA) and the University California, Los Angeles in compliance with all applicable Peru and US federal regulations governing the protection of human participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Zoni AC, Gonzalez MA, Sjogren HW. Syphilis in the most at-risk populations in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis 2013;17:e84–92. 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections—2008. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caceres CF, Konda KA, Salazar X et al. New populations at high risk of HIV/STIs in low-income, urban coastal Peru. AIDS Behav 2008;12:544–51. 10.1007/s10461-007-9348-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva-Santisteban A, Raymond HF, Salazar X et al. Understanding the HIV/AIDS epidemic in transgender women of Lima, Peru: results from a sero-epidemiologic study using respondent driven sampling. AIDS Behav 2012;16:872–81. 10.1007/s10461-011-0053-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59(Rr-12):1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zetola NM, Klausner JD. Syphilis and HIV infection: an update. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:1222–8. 10.1086/513427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullick S, Beksinksa M, Msomi S. Treatment for syphilis in antenatal care: compliance with the three dose standard treatment regimen. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:220–2. 10.1136/sti.2004.011999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myer L, Abdool Karim SS, Lombard C et al. Treatment of maternal syphilis in rural South Africa: effect of multiple doses of benzathine penicillin on pregnancy loss. Trop Med Int Health 2004;9:1216–21. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01330.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotchford K, Lombard C, Zuma K et al. Impact on perinatal mortality of missed opportunities to treat maternal syphilis in rural South Africa: baseline results from a clinic randomized controlled trial. Trop Med Int Health 2000;5:800–4. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P et al. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1337–44. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilmarx PH, Mutasa-Apollo T. Patching a leaky pipe: the cascade of HIV care. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2013;8:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long CM, Klausner JD, Leon S et al. Syphilis treatment and HIV infection in a population-based study of persons at high risk for sexually transmitted disease/HIV infection in Lima, Peru. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:151–5. 10.1097/01.olq.0000204506.06551.5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect 1999;75:3–17. 10.1136/sti.75.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bautista CT, Sanchez JL, Montano SM et al. Seroprevalence of and risk factors for HIV-1 infection among South American men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:498–504. 10.1136/sti.2004.013094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Boni R, Veloso VG, Grinsztejn B. Epidemiology of HIV in Latin America and the Caribbean. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014;9:192–8. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vagenas P, Ludford KT, Gonzales P et al. Being unaware of being HIV-infected is associated with alcohol use disorders and high-risk sexual behaviors among men who have sex with men in Peru. AIDS Behav 2014;18:120–7. 10.1007/s10461-013-0504-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludford KT, Vagenas P, Lama JR et al. Screening for drug and alcohol use disorders and their association with HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in Peru. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e69966 10.1371/journal.pone.0069966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB et al. AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd ed Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA 2003;290:1510–4. 10.1001/jama.290.11.1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauhan M, Serisha B, Sankar KN et al. Audit of the use of benzathine penicillin, post-treatment syphilis serology and partner notification of patients with early infectious syphilis. Int J STD AIDS 2006;17:200–2. 10.1258/095646206775809231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samoff E, Koumans EH, Gibson JJ et al. Pre-treatment syphilis titers: distribution and evaluation of their use to distinguish early from late latent syphilis and to prioritize contact investigations. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:789–93. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b3566b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sena AC, Wolff M, Behets F et al. Response to therapy following retreatment of serofast early syphilis patients with benzathine penicillin. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:420–2. 10.1093/cid/cis918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos GM, Wilson EC, Rapues J et al. HIV treatment cascade among transgender women in a San Francisco respondent driven sampling study. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:430–3. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sevelius JM, Patouhas E, Keatley JG et al. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med 2014;47:5–16. 10.1007/s12160-013-9565-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia PJ, Carcamo CP, Chiappe M et al. Rapid syphilis tests as catalysts for health systems strengthening: a case study from Peru. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e66905 10.1371/journal.pone.0066905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim MS, Hocking JS, Hellard ME et al. SMS STI: a review of the uses of mobile phone text messaging in sexual health. Int J STD AIDS 2008;19:287–90. 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menacho LA, Blas MM, Alva IE et al. Short text messages to motivate HIV testing among men who have sex with men: a qualitative study in Lima, Peru. Open AIDS J 2013;7:1–6. 10.2174/1874613601307010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christopoulos KA, Massey AD, Lopez AM et al. “Taking a half day at a time:” patient perspectives and the HIV engagement in care continuum. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:223–30. 10.1089/apc.2012.0418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.García PJ, Holmes KK, Cárcamo CP et al. Prevention of sexually transmitted infections in urban communities (Peru PREVEN): a multicomponent community-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:1120–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61846-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campos PE, Buffardi AL, Carcamo CP et al. Reaching the unreachable: providing STI control services to female sex workers via mobile team outreach. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e81041 10.1371/journal.pone.0081041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blas MM, Alva IE, Cabello R et al. Internet as a tool to access high-risk men who have sex with men from a resource-constrained setting: a study from Peru. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:567–70. 10.1136/sti.2007.027276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]