Abstract

Objectives

To examine: (1) changes in polypharmacy in 1997, 2002, 2007 and 2012 and; (2) changes in potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP) prevalence and the relationship between PIP and polypharmacy in individuals aged ≥65 years over this period in Ireland.

Methods

This repeated cross-sectional study using pharmacy claims data included all individuals eligible for the General Medical Services scheme in the former Eastern Health Board region of Ireland in 1997, 2002, 2007 and 2012 (range 338 025–539 752 individuals). Outcomes evaluated were prevalence of polypharmacy (being prescribed ≥5 regular medicines) and excessive polypharmacy (≥10 regular medicines) in all individuals and PIP prevalence in those aged ≥65 years determined by 30 criteria from the Screening Tool for Older Persons’ Prescriptions.

Results

The prevalence of polypharmacy increased from 1997 to 2012, particularly among older individuals (from 17.8% to 60.4% in those aged ≥65 years). The adjusted incident rate ratio for polypharmacy in 2012 compared to 1997 was 4.16 (95% CI 3.23 to 5.36), and for excessive polypharmacy it was 10.53 (8.58 to 12.91). Prevalence of PIP rose from 32.6% in 1997 to 37.3% in 2012. High-dose aspirin and digoxin prescribing decreased over time, but long-term proton pump inhibitors at maximal dose increased substantially (from 0.8% to 23.8%). The odds of having any PIP in 2012 were lower compared to 1997 after controlling for gender and level of polypharmacy, OR 0.39 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.4).

Conclusions

Accounting for the marked increase in polypharmacy, prescribing quality appears to have improved with a reduction in the odds of having PIP from 1997 to 2012. With growing numbers of people taking multiple regular medicines, strategies to address the related challenges of polypharmacy and PIP are needed.

Keywords: CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY, PRIMARY CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a large-scale study of pharmacy claims data assessing trends in prescribing across a long time period.

Individual-level data on dispensed medicines allow for the relationship between two common prescribing issues in older people to be examined over time.

Results relating to those under the age of 70 years may be less generalisable due to over-representation of individuals with lower socioeconomic status.

The potentially inappropriate prescribing criteria used were published in 2008, so prescribers may not have had knowledge of inappropriateness of some medicines in the early study years.

Introduction

The volume of medicines being prescribed has risen in recent years.1 Despite this, concerns have been raised that patients who are eligible for evidence-based treatments are not receiving them.2 Set against the background of a rising burden of illness, some commentators have called for the use of more medicines to alleviate pain and disability, prolong life and prevent avoidable disease.2 3

In contrast, there is increasing concern about overdiagnosis and overtreatment, particularly in elderly patients.4 5 There has been a proliferation of clinical guidelines focused on single conditions, which fail to account for the growing cohort of patients with multimorbidity.6 7 In older people, there has been particular focus on polypharmacy, commonly defined as the use of five or more regular medicines. Although polypharmacy has been used as a crude marker of prescribing quality, it can in many cases, such as multimorbidity, be entirely appropriate.8 9 A clearer indicator of medicines safety and prescribing quality is potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP), the use of a medicine such that the harms outweigh the benefits,10 as exposure to PIP medicines is associated with adverse outcomes, including adverse drug events and hospitalisations.10 11

These two issues are inter-related, as polypharmacy is the single biggest predictor of being prescribed a PIP medicine.10 12 Although it appears that polypharmacy and PIP have become more widespread in recent years, the relationship between these issues over time is not clearly understood.

In this study, we analyse pharmacy claims data over a 15 year time period from 1997 to 2012 in primary care in Ireland to examine: (1) the change in prescribing patterns and rates of polypharmacy (being prescribed ≥5 regular medicines) in all individuals, (2) the change in prevalence of PIP in individuals aged ≥65 years and (3) the relationship between PIP and polypharmacy in these older individuals.

Methods

Study design and setting

A repeated cross-sectional study was conducted using patient-level dispensing data from an administrative pharmacy claims database in the years 1997, 2002, 2007 and 2012, a period of 15 years. Data were included for all people eligible for the General Medical Services (GMS) scheme in the study years in the former Eastern Health Board (EHB) region of Ireland, where 29.1% of the national population resided in 2012.13

The GMS scheme is a means-tested form of public health cover in Ireland providing free health services, including most prescribed medicines, to people based on income and age, although a monthly copayment per prescription item was introduced in 2010. As of 2012, 40.1% of the general Irish population and 96.5% of those over 70 years were covered by the scheme.13 14 From 2002 to 2008, all people aged 70 years or over were automatically eligible for the scheme and since January 2009, a higher income threshold was applied to this age group compared to the general population.

The Health Services Executive-Primary Care Reimbursement Service (HSE-PCRS) database used for this study contains dispensing records of medicines prescribed to patients in primary care by their general practitioners. For this analysis, medicines were classified into drug classes based on the first five characters of their WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code and only dispensing data relating to individual patients were included. Specific ethical approval for this study was not required as all data were fully anonymised.

Data analysis

Regular medicines and polypharmacy in the total population

The number of regular medicines (dispensed in at least three consecutive months) per person during each study year was analysed to determine the distribution of individuals by age group and number of regular medicines (category aggregated at 15 or more medicines). The most prevalent medicines (grouped by level 5 ATC code) were also examined by determining the number of individuals to whom each medicine was regularly dispensed. For the years 1997 to 2007, this was directly standardised by age group and gender to the 2012 GMS population of the EHB region to account for changing demographics and to allow comparison across years.

The prevalence of polypharmacy (being dispensed five or more regular medicines in the study year) and excessive polypharmacy (conventionally defined as 10 or more regular medicines) was calculated.15 Negative binomial regression was used to quantify the change in the rate of these outcomes associated with study year (using 1997 as the reference year), controlling for age group and gender. Interaction terms between these independent variables were included if they provided a statistically significant improvement to model fit. Incident rate ratios (IRR) with 95% CIs are presented. Negative binomial models were used over Poisson models due to over-dispersion in the rates of polypharmacy.16

PIP in older individuals

Prescribing inappropriateness was assessed in individuals aged ≥65 years using a subset of criteria from the Screening Tool for Older Persons’ Prescription (STOPP). This explicit measure of PIP was applied as it was developed for use in older European populations and includes more medicines than the Beers criteria which are commonly prescribed in the study setting.17 18 Analysis was restricted to older individuals, as explicit measures of PIP such as STOPP have not been validated in younger age groups. Thirty of sixty-five criteria (see online supplementary appendix S1) were applicable to the information in the HSE-PCRS administrative data set and lack of detailed clinical information precluded application of the remaining criteria, consistent with other studies applying STOPP to pharmacy claims data.19 PIP prevalence was assessed by the percentage of individuals with any PIP criteria. Prevalence for each individual STOPP criteria was also determined to examine the most common forms of PIP over the study period.

The relationship between PIP and polypharmacy in older individuals

Unadjusted logistic regression was performed to assess the change in odds of having any PIP over the study years and ORs with 95% CIs are presented. The relationship between PIP prevalence (dependent variable) and rates of polypharmacy across years was explored using multivariate logistic regression. Covariates included in the model were year (1997 as the reference), level of polypharmacy (0–4 medicines (reference), 5–9 medicines, and ≥10 medicines) and gender. A sensitivity analysis was performed post hoc to assess the impact of excluding the STOPP criterion with the largest contribution to PIP in 2012, long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) at maximal dose, from the analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). Significance at p<0.05 was assumed.

Results

Regular medicines and polypharmacy in the total population

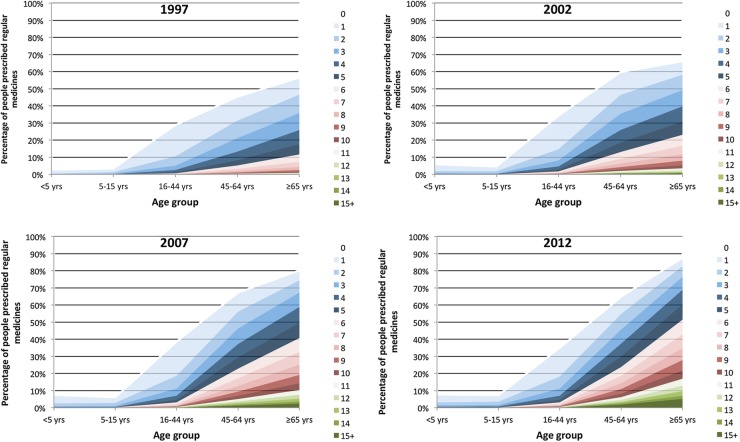

The number of individuals included in this study in 1997, 2002, 2007 and 2012 were 338 025, 344 270, 373 007 and 539 752, respectively. Figure 1 shows the proportion of each age group by the number of regular medicines prescribed for each study year. There is a clear increase in the proportion of individuals on higher numbers of medicines, particularly in the two oldest age groups.

Figure 1.

Percentage of eligible population by number of regular medicines for the years 1997–2012.

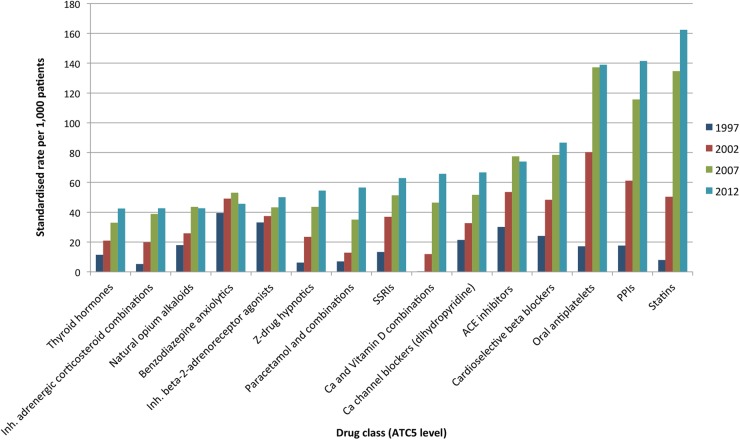

The rates of prescription per 1000 GMS-eligible patients of the 15 most common regular medicines in 2012 compared to the age-standardised and sex-standardised rates in previous years are shown in figure 2. Statins were prescribed to the highest number of individuals, and like antiplatelet drugs and PPIs, there have been large increases in the numbers of people on these medicines over the study period. Several other cardiovascular drugs were among the most commonly prescribed medicines. Benzodiazepine anxiolytics were one of the few medicines not to show a year on year increase over this time. Prescribing of related medicines, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and non-benzodiazepine (Z-drug) hypnotics, did show an upward trend during the study period.

Figure 2.

Standardised rates of prescribing of most common regular medicines in all individuals in 2012. Abbreviations: SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors.

Of those aged 45–64 years, the percentage with polypharmacy (on five or more regular medicines) increased from 8.3% to 30.2% over the study period, and for those aged ≥65 years it rose from 17.8% to 60.4%. A similar trend was observed for excessive polypharmacy (on 10 or more regular medicines), with the prevalence increasing during this time from 0.8% to 8.3% in those aged 45–64 years and from 1.5% to 21.9% in people ≥65 years.

In the negative binomial regression analysis (table 1), the adjusted IRR for polypharmacy in 2012 compared to 1997 is 4.16 (95% CI 3.23 to 5.36). In the model for excessive polypharmacy, the adjusted IRR for 2012 compared to 1997 is 10.53 (95% CI 8.58 to 12.91). For both of these outcomes, there was a trend of increasing adjusted IRR for polypharmacy across the study years controlling for age and gender.

Table 1.

Adjusted negative binomial regression models for polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy in all individuals

| Polypharmacy* |

Excessive polypharmacy† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted IRR‡ | 95% CI | Adjusted IRR§ | 95% CI | |

| Year | ||||

| 1997 (reference) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| 2002 | 2.18 | (1.69 to 2.82) | 3.53 | (2.86 to 4.36) |

| 2007 | 3.49 | (2.71 to 4.49) | 8.07 | (6.55 to 9.93) |

| 2012 | 4.16 | (3.23 to 5.36) | 10.53 | (8.58 to 12.91) |

*Polypharmacy defined as 5 or more regular medicines.

†Excessive polypharmacy defined as 10 or more regular medicines.

‡Adjusted for age group and gender (both significant, p<0.01).

§Adjusted for age group, gender and age group-gender interaction (all significant, p<0.01).

IRR, incident rate ratio.

PIP in older individuals

There were 78 489 individuals aged 65 or above included in 1997, 121 726 in 2002, 129 162 in 2007 and 133 884 in 2012. The prevalence of PIP in these individuals in 1997 using 30 STOPP criteria was 32.6%. This fell to 28.6% in 2002; however, the percentage with PIP increased in the more recent study years to 32.8% in 2007 and 37.3% in 2012 (see online supplementary appendix S2).

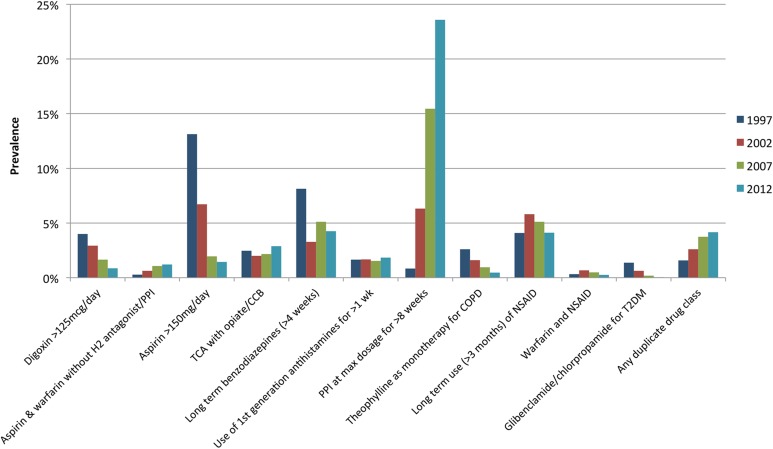

A number of PIP criteria decreased in prevalence across the study period, with the largest reductions in prescribing of high doses of aspirin and digoxin (figure 3). Although the rates of long-term use of benzodiazepines and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have fluctuated across the study period, the prevalence of these criteria has remained high (>3%). An increase in duplication of drug classes was observed, in particular duplicate opioids. The largest increase in prevalence of a criterion was PPIs at maximum dosage for >8 weeks, which rose from 0.8% in 1997 to 23.6% in 2012. This is the major contributor to the overall PIP prevalence and a sensitivity analysis excluding this criterion showed a consistent decrease in overall PIP prevalence (32.3%, 24.9%, 22.6% and 20.8% from 1997 to 2012).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of most common types of PIP in individuals aged ≥65 years. Abbreviations: H2, histamine-2 receptor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; CCB, calcium channel blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The relationship between PIP and polypharmacy in older individuals

The trend of PIP prevalence across the study years was confirmed in the univariate logistic regression where the odds of having any PIP were lower in 2002 compared to 1997 and then rose in 2007 and 2012 compared to 1997 (table 2). After adjusting for gender and level of polypharmacy in the multivariable logistic regression, a trend of reducing odds of having a PIP across the study years is observed. The adjusted OR for having a PIP for polypharmacy compared to no polypharmacy is 6.83 (95% CI 6.73 to 6.93) and for excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medicines) compared to no polypharmacy is 22.05 (95% CI 21.57 to 22.54). In the sensitivity analysis using prevalence of any PIP excluding long-term maximal dose PPI as the outcome, an even greater reduction in the odds of having a PIP was observed over the study period (adjusted OR for PIP in 2012 is 0.2 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.2) compared to in 1997).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models for having any PIP criteria in individuals aged ≥65 years

| Any PIP (unadjusted) |

Any PIP (adjusted) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR* | 95% CI | |

| Year | ||||

| 1997 (reference) | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| 2002 | 0.83 | (0.81 to 0.84) | 0.53 | (0.52 to 0.54) |

| 2007 | 1.01 | (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.38 | (0.38 to 0.39) |

| 2012 | 1.23 | (1.21 to 1.25) | 0.39 | (0.39 to 0.40) |

*Adjusted for level of polypharmacy (0–4 medicines (reference), 5–9 medicines, ≥10 medicines) and gender (all significant, p<0.01).

PIP, potentially inappropriate prescribing.

Discussion

Principal findings

Between 1997 and 2012, there was a substantial increase in the prescribing of regular medicines, particularly in older adults, with a fourfold increase in polypharmacy and a 10-fold increase in excessive polypharmacy, independent of age and gender. PIP prevalence also rose, largely due to increasing maximal dose PPI use that masked the reduction across most of the other PIP medicines. After controlling for changes in polypharmacy over time, there has been a reduction in the odds of having any PIP in recent years.

Findings in the context of the literature

Other studies have also reported an increase over time in drugs prescribed to individual patients, though they examined different time frames to the present study.20–22 This has implications for healthcare provision; for example, the number of office-based visits by elderly patients with polypharmacy quadrupled between 1990 and 2000 in the USA.23 Higher rates of excessive polypharmacy were observed in this study, possibly due to the proportion of individuals with lower incomes being included, as lower socioeconomic status and deprivation can be associated with polypharmacy, multimorbidity and lower quality prescribing.21 24 25

Much research on trends in PIP found decreasing prevalence over time,26–28 and the number of regular medicines or polypharmacy was consistently reported as being the strongest predictor of PIP.26 27 In relation to specific PIP medicines, significant quantities of maximal dose PPIs continue to be prescribed. This is despite the potential cost-savings of optimising use being raised in the USA and Ireland ($47.1 billion and €40.5 million per annum)19 29 and concerns regarding the clinical implications of such PPI overprescribing.30 Long-term NSAIDs and benzodiazepine use in older people, defined as inappropriate in the STOPP and Beers criteria,18 is also of concern as such prescribing remains prevalent across countries and is associated with high-risk adverse events in vulnerable elderly patients.31 32

Implications for policy and practice

The growth in prescribing in recent years, particularly in middle and older age groups, means more individuals have polypharmacy than ever before (see online supplementary appendix 2), suggesting that a threshold of five or more medicines may no longer specifically identify higher risk patients.33 Polypharmacy was estimated to cost US health plans at least $50 billion annually in 2002 and continued growth since then is likely to have had a major impact on pharmaceutical expenditure.34

A number of factors may be contributing to increasing polypharmacy. The growing prevalence of multimorbidity twinned with the use of single condition-focused treatment guidelines are likely to have contributed to the higher rates of polypharmacy.6 More patient-centred care may help address this conflict between evidence-based medicine and effective multimorbidity management.35 There may also be a growing acceptance that the medicalisation of older age is of benefit to patients.3 Prescribing indications for common medicines such as statins and PPIs have expanded since they were first marketed and the use of such agents has become increasingly widespread.36 37 It appears that the mass prescription of preventive medicines is becoming more acceptable, as illustrated by the increasing number of people on statins.38 A prescription no longer signals treatment of a sick patient and this has implications for what polypharmacy indicates in modern healthcare.38

The relationship between polypharmacy and use of PIP drugs is complex. While polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy are strongly associated with PIP, the picture that emerges in our setting is that when the number of prescribed medicines is accounted for, the chance of being prescribed a PIP medicine has decreased over time (table 3). These analyses illustrate the complex, competing factors influencing prescribing. On the one hand, there is increasing medicines use being driven by clinical practice guidelines and other forms of external evidence that mandate prescribing. On the other hand, there is an awareness of iatrogenic harm and that the use of PIP medicines needs to be justified and, if possible, limited. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy have been effective in reducing inappropriate prescribing, but the clinical significance of such improvements is unclear.39 Deprescribing of medications among older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy to reduce the drug burden may also yield patient benefits; however, the evidence base for this approach needs to be further developed.40

Study strengths and weaknesses

The large study population and length of the follow-up period means these results are more likely to be generalisable and less likely to be due to short-term fluctuations in prescribing practice. The study utilises primary care dispensing data from a pharmacy claims database, which allows for medicines use of individuals to be explored as opposed to population-level drugs consumption. Dispensing data sources, unlike prescribing databases, can account for primary non-adherence to prescriptions and so is more likely to reflect actual medicines use by patients; however, we do not know if patients actually take the medicines dispensed or if they are taking over-the-counter medicines. No clinical or diagnostic information is available in this data source. Therefore, only a subset of STOPP criteria could be applied, possibly underestimating the actual prevalence of PIP in this population. There could also be clinical justification for some instances of PIP, which cannot be identified without a full patient medical record. For example, long-term PPIs at high doses may be appropriate in managing Barrett's oesophagus.

A further limitation of this study is that only people eligible for the means-tested GMS scheme in the EHB region could be included. Deprived individuals may therefore be over-represented, as are females and the younger and older populations who are possibly more likely to have polypharmacy.21 However, for much of the study period, all over 70s were eligible for the GMS scheme and so, for the older population, the findings are likely to be largely representative and not biased by socioeconomic status. Some forms of prescribing included may not have been considered potentially inappropriate from evidence available before the publication of the STOPP criteria in 2008. The reduction in prevalence of such criteria may illustrate evidence being incorporated into practice as it became available.

Conclusions

This study shows a marked increase in prescribed medicines over a relatively short time and increasing polypharmacy is the main driver of exposure to PIP. Prescribing of certain PIP medicines has declined, which could indicate an increasing recognition among prescribers that these medicines may be potentially inappropriate. Reassuringly, after controlling for increasing polypharmacy, the odds of older individuals being exposed to PIP have reduced with time; given the increased medicines burden, clinicians seem to be prescribing more appropriately.

In the future, two related issues need to be addressed. First, quality improvement strategies and interventions should be considered to improve prescribing appropriateness further, particularly for prevalent PIP medicines such as benzodiazepines, NSAIDs and PPIs. Second, interventions for patients need to make clear the trade-off between taking more medicines to prevent disease or minimise disability and the potential for iatrogenic harm from PIP drugs that occur more commonly with polypharmacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the HSE-PCRS for providing access to the administrative pharmacy claims database used for this study.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Frank Moriarty at @FrankMoriarty

Contributors: TF and FM conceived the study and all authors were involved in designing the study. Data were provided by KB. CH and FM carried out the statistical analysis. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data. FM wrote the first draft of the paper and all authors contributed to subsequent drafts. TF is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the Health Research Board of Ireland (HRB) through the HRB Centre for Primary Care Research (grant no. HRC/2007/1) and the HRB PhD Scholars Programme in Health Services Research (grant no. PHD/2007/16).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interests form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. The global use of medicines: outlook through 2016. Danbury, CT: IMS Health, 2012.

- 2.Gurwitz J. Polypharmacy: a new paradigm for quality drug therapy in the elderly? Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1957–9. 10.1001/archinte.164.18.1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebrahim S. The medicalisation of old age. BMJ 2002;324:861–3. 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moynihan R, Glasziou P, Woloshin S et al. Winding back the harms of too much medicine. BMJ 2013;346:f1271 10.1136/bmj.f1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan DJ, Wright SM, Dhruva S. Update on medical overuse. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:120–4. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunt LM, Kreiner M, Brody H. The changing face of chronic illness management in primary care: a qualitative study of underlying influences and unintended outcomes. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:452–60. 10.1370/afm.1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guthrie B, Payne K, Alderson P et al. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ 2012;345:e6341 10.1136/bmj.e6341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes C, Cooper J, Ryan C. Going beyond the numbers—a call to redefine polypharmacy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77:915–16. 10.1111/bcp.12284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Payne RA, Abel GA, Avery AJ et al. Is polypharmacy always hazardous? A retrospective cohort analysis using linked electronic health records from primary and secondary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77:1073–82. 10.1111/bcp.12292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cahir C, Moriarty F, Teljeur C. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and vulnerability and hospitalization in older community-dwelling patients. Ann Pharmacother 2014;48:1546–54. 10.1177/1060028014552821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahir C, Bennett K, Teljeur C et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and adverse health outcomes in community dwelling older patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77:201–10. 10.1111/bcp.12161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goulding M. Inappropriate medication prescribing for elderly ambulatory care patients. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:305–12. 10.1001/archinte.164.3.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Service Executive. Primary Care Reimbursement Service Annual Report. Dublin, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Central Statistics Office. Population estimates. http://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=PEA01&PLanguage=0 (accessed 10 Mar 2015).

- 15.Blanco-Reina E, Ariza-Zafra G, Ocaña-Riola R et al. Optimizing elderly pharmacotherapy: polypharmacy vs. undertreatment. Are these two concepts related? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2015;71:199–207. 10.1007/s00228-014-1780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychol Bull 1995;118:392–404. 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S et al. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person's Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;46:72–83. 10.5414/CPP46072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moriarty F, Bennett K, Fahey T et al. Longitudinal prevalence of potentially inappropriate medicines and potential prescribing omissions in a cohort of community-dwelling older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2015;71:473–82. 10.1007/s00228-015-1815-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cahir C, Fahey T, Tilson L et al. Proton pump inhibitors: potential cost reductions by applying prescribing guidelines. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:408 10.1186/1472-6963-12-408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linjakumpu T, Hartikainen S, Klaukka T et al. Use of medications and polypharmacy are increasing among the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:809–17. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00411-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haider SI, Johnell K, Thorslund M et al. Trends in polypharmacy and potential drug-drug interactions across educational groups in elderly patients in Sweden for the period 1992–2002. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007;45:643–53. 10.5414/CPP45643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hovstadius B, Hovstadius K, Astrand B et al. Increasing polypharmacy—an individual-based study of the Swedish population 2005–2008. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2010;10:16 10.1186/1472-6904-10-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aparasu RR, Mort JR, Brandt H. Polypharmacy trends in office visits by the elderly in the United States, 1990 and 2000. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2005;1:446–59. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380: 37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fialová D, Topinková E, Gambassi G et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use among elderly home care patients in Europe. JAMA 2005;293:1348–58. 10.1001/jama.293.11.1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carey IM, De Wilde S, Harris T et al. What factors predict potentially inappropriate primary care prescribing in older people? Drugs Aging 2008;25:693–706. 10.2165/00002512-200825080-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price SD, Holman CD, Sanfilippo FM et al. Are older Western Australians exposed to potentially inappropriate medications according to the Beers Criteria? A 13-year prevalence study. Australas J Ageing 2014;33:E39–48. 10.1111/ajag.12136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hovstadius B, Petersson G, Hellström L et al. Trends in inappropriate drug therapy prescription in the elderly in Sweden from 2006 to 2013: assessment using national indicators. Drugs Aging 2014;31:379–86. 10.1007/s40266-014-0165-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansen ME, Huerta TR, Richardson CR. National use of proton pump inhibitors from 2007 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1856–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grady D, Redberg RF. Less is more: how less health care can result in better health. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:749–50. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guthrie B, McCowan C, Davey P et al. High risk prescribing in primary care patients particularly vulnerable to adverse drug events: cross sectional population database analysis in Scottish general practice. BMJ 2011;342:d3514 10.1136/bmj.d3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2014:E1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation: making it safe and sound. London: The King's Fund, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bushardt RL, Massey EB, Simpson TW et al. Polypharmacy: misleading, but manageable. Clin Interv Aging 2008;3:383–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyd CM, Kent DM. Evidence-based medicine and the hard problem of multimorbidity. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:552–3. 10.1007/s11606-013-2658-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobert JA. Lovastatin and beyond: the history of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003;2:517–26. 10.1038/nrd1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanderhoff BT, Tahboub RM. Proton pump inhibitors: an update. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:273–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldacre B, Smeeth L. Mass treatment with statins. BMJ 2014;349:g4745 10.1136/bmj.g4745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patterson S, Cadogan C, Kerse N et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(10):CD008165 10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Hilmer SN. Discontinuing drug treatments. We need better evidence to guide deprescribing. BMJ 2014;349:g7013 10.1136/bmj.g7013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]