Abstract

Objectives

In 2003, a skin cancer screening campaign based on total body skin examination was launched in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. 20% of adults aged 20 and over were screened. In 2008, a 48% decline in melanoma mortality was reported. In the same year, skin screening was extended to the rest of Germany. We evaluated whether melanoma mortality trends decreased in Germany as compared with surrounding countries where skin screening is uncommon. We also evaluated whether the initial decreasing mortality trend observed in Schleswig-Holstein was maintained with a longer follow-up.

Setting and participants

Regional and national melanoma mortality data from 1995 to 2013 were extracted from the GEKID database and the Federal Statistical Office. Mortality data for Germany and surrounding countries from 1980 to 2012 were extracted from the WHO mortality database.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Age-adjusted (European Standard Population) mortality rates were computed and joinpoint analysis performed for Schleswig-Holstein, Germany and surrounding countries.

Results

In Schleswig-Holstein, melanoma mortality rates declined by 48% from 2003 to 2008, and from 2009 to 2013 returned to levels observed before screening initiation. During the 5 years of the national programme (2008–2012), melanoma mortality rates increased by 2.6% (95% CI −0.1 to 5.2) in men and 0.02% (95% CI −1.8 to 1.8) in women. No inflexion point in trends was identified after 2008 that could have suggested a decreasing melanoma mortality. Trends of cutaneous melanoma mortality in Germany from 1980 to 2012 did not differ from those observed in surrounding countries.

Conclusions

The transient decrease mortality in Schleswig-Holstein followed by return to pre-screening levels could reflect a temporal modification in the reporting of death causes. An in-depth evaluation of the screening programme is required.

Keywords: Melanoma, Screening, Mortality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study replicates, with a follow-up time doubled, the analysis that was conducted in the region of Schleswig–Holstein, Germany, showing a 48% decline in cutaneous melanoma mortality 5 years after initiation of a skin cancer screening campaign based on total body skin examination.

In addition, this study evaluates using a similar method, with 5 years of follow-up, the impact in the whole of Germany where a skin cancer screening programme was introduced since 2008.

A limitation of such an approach, as in the original approach that was used in Schleswig-Holstein, is the ecological design.

Another limitation is that there is currently a lack of useful process and outcome evaluation of the skin cancer screening. This represents a major failure of the German screening programme.

However, the current unique situation in Germany represents a quasi-experimental setting in Europe to evaluate whether such a massive introduction of total body skin examination in the general population is effective in decreasing melanoma mortality.

Introduction

Many public health agencies like the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) or the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK do not recommend skin cancer screening. This practice, however, tends to increase: 14.5% of adults in the USA in 2000 had at least one total body skin examination (TBSE), this figure increased to 19.8% in 2010.1

In 2003, a skin cancer screening campaign (the SCREEN (Skin Cancer Research to Provide Evidence for Effectiveness of Screening in Northern Germany) project) was initiated in the federal state of Schleswig–Holstein in Germany.2 This campaign was based on TBSE offered from July 2003 to June 2004 to individuals aged 20 and over by dermatologists and by non-dermatologist practitioners who had followed an 8 h training course. These TBSE were fully covered by health insurances; physicians received a financial incentive of €15 per screening. No invitation or follow-up system was implemented, but the population was informed about the campaign by a large-scale mass media campaign. The participation rate was 19% (27% in women and 10% in men) to 21.5%.3 4 In 2008, melanoma mortality rates were reported to have dropped by 47% and 49% in Schleswig–Holstein men and women, respectively.5

Many considered that the 5-year results of the SCREEN project represented compelling evidence that skin cancer screening based on TBSE could be effective.5 6 In 2008, a national programme was implemented in Germany, including Schleswig–Holstein, following screening procedures adopted in the SCREEN project but starting at age 35.7 Simulation studies foresaw that biennial TBSE of the German population aged 35–85 years and a 20% participation would reduce melanoma mortality by 45% 20 years after screening implementation.8 Screening in the national programme experienced divergences from the initial programme as some insurance companies agreed to reimburse additional services proposed by practitioners. Screening could be performed in adults less than 35 years of age with a shorter interval between screening rounds, and assessment of pigmented lesions could be carried out using computer or video technologies.9

In this study, we evaluated whether the reported decreases in melanoma mortality in Schleswig–Holstein were maintained over time. Then we analysed changes in melanoma mortality in Germany in the 5 years following implementation of the national programme using statistical methods similar to those used for the evaluation of the SCREEN project in Schleswig–Holstein. We also computed melanoma mortality trends in Germany for different age groups and compared them with trends in surrounding countries where a similar skin cancer screening programme does not exist.

Material and methods

Incidence and regional mortality data in Germany were extracted from the GEKID database.10 Melanoma incidence data were available for the period 2003–2011. Melanoma mortality was extracted for the whole of Germany as well as for Schleswig–Holstein from the GEKID database for the period 1995–2012 and from the Federal Statistical Office for the period 1998–2013.11 The latter data source was used for completing the GEKID database for the year 2013. Both data sources, GEKID and Federal Statistical Office, reported identical figures for years they had in common, ie 1998–2012. For the comparison of melanoma mortality rates, melanoma mortality data of Germany and of surrounding countries (the Czech Republic, Denmark, Austria, Belgium, France, Poland, the Netherlands and Switzerland) were extracted from the WHO mortality database (update of November 2014). International classification of disease (ICD) codes of extracted data were ICD 8 172, ICD 9 172 and ICD 10 C43.

Age-standardised (European Standard Population) incidence and mortality rates were computed. For Germany and surrounding countries, annual per cent changes (APC) in mortality were then computed for the period 1980–2012, and for the period 2008–2012, that is for the 5 years following the introduction of screening in Germany.

Temporal trends of melanoma mortality were analysed from 1980 to 2012 in Germany and surrounding countries using joinpoint regression.12 Joinpoint software fits a series of straight lines connected on a common point, called ‘joinpoint’, on a logarithmic scale to the annual age-standardised rates. The selected number of lines and points of inflexion, if any, is based on the simplest model that the data allow.13 The programme uses permutation analysis with a grid search algorithm to identify inflexions in trends with an overall statistical significance level of 0.05. We kept default settings in the programme, that is, allowing up to five possible joinpoints during 1980–2012, with three observations from a joinpoint to either end of the data and four observations between two joinpoints. We reported trends for the last uninterrupted segment identified in the joinpoint regression by age groups: less than 60, 60–74, and 75 and over.

Results

Melanoma mortality in Schleswig–Holstein

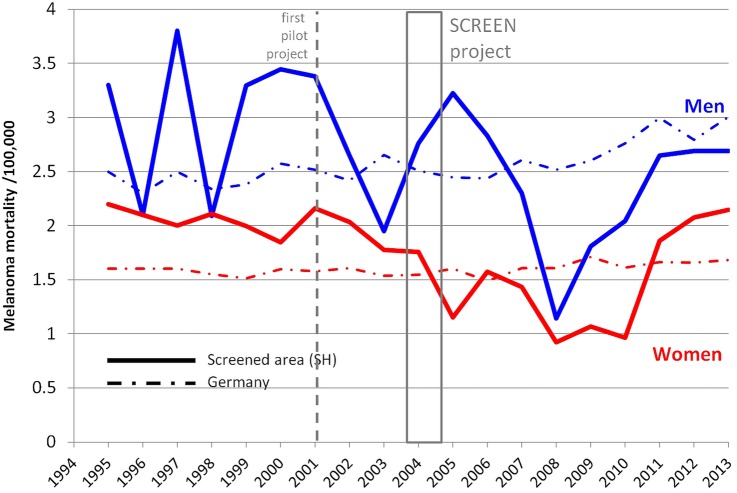

Melanoma mortality dropped in the years immediately following the pilot project that took place in 2001 (figure 1). In 2008, melanoma mortality rates were well below the rates reported for Germany. In 2009–2010, a doubling of mortality rates took place, and in 2012 and 2013, the melanoma rates were close to the rates observed before the pilot project.

Figure 1.

Trend in cutaneous melanoma mortality in the screened area Schleswig–Holstein (SH) as compared with the whole of Germany. Data from the Federal Statistical Office (http://www.gbe-bund.de) as of 15 December 2014 and from GEKID as of 10 December 2014. Box=period of SCREEN project (Skin Cancer Research to Provide Evidence for Effectiveness of Screening in Northern Germany) (July 2003–June 2004).

Melanoma incidence and mortality in Germany

Schleswig–Holstein has a population size of 2 806 000 people, it represents 3.5% of all Germany. In Schleswig–Holstein before the SCREEN project started (1998–1999), the age-standardised melanoma mortality rate (World Standard Population) was 1.9 per 100 000 for men and 1.4 per 100 000 for women. Melanoma mortality declined by 47% to 1.0 per 100 000 men and by 49% to 0.7 per 100 000 women by 2008/2009. The APC in the period 2000–2009 was −7.5% (95% CI −14.0 to −0.5) for men and −7.1% (95% CI −10.5 to −2.9) for women. In each of the four adjacent regions and in the rest of Germany, the mortality rates were stable.5

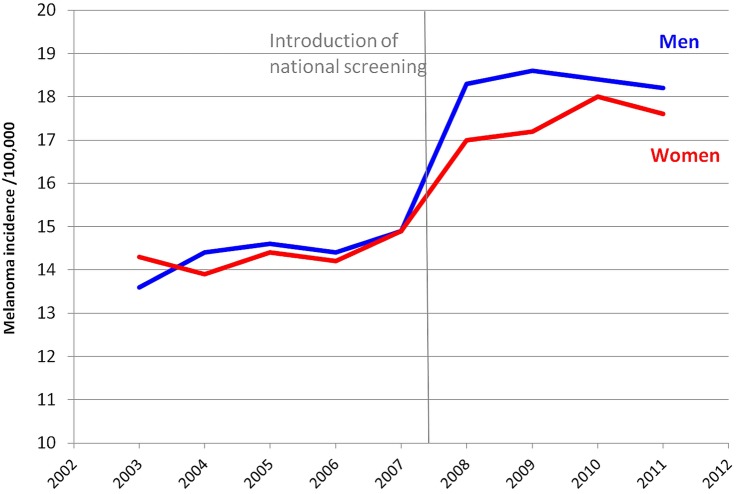

Overall, in Germany, the average participation rate in the skin cancer screening programme from January 2009 to December 2010 reached 30.8%.14 The launch of the national screening programme was immediately followed by a 29% rise in the incidence of cutaneous melanoma in both sexes (figure 2), from about 14.5 cases per 100 000 person-years in 2006 to 18.0 cases per 100 000 person-years in 2010.

Figure 2.

Trend in cutaneous melanoma incidence in Germany. Data from GEKID as of 10 December 2014. Vertical line=introduction of screening at a national level. Note that for better display, Y-axis starts at 10 cases per 100 000 person-years.

From 1980 to 2012, the melanoma mortality rate in Germany remained flat with an APC of 0.44% in men and of −0.15% in women (table 1).

Table 1.

Melanoma mortality annual per cent change for all ages for men and women between 1980 and 2012 and in the past 5 years for Germany and surrounding countries

| Country | Men |

Women |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual per cent change (%) (95% CI) 1980–2012 |

Annual per cent change (%) (95% CI) 2008–2012 |

Annual per cent change (%) (95% CI) 1980–2012 |

Annual per cent change (%) (95% CI) 2008–2012 |

|

| Germany | 0.44 (0.26 to 0.62) | 2.57 (−0.10 to 5.24) | −0.15 (−0.30 to 0.00) | 0.02 (−1.79 to 1.82) |

| Czech Republic* | −0.55 (−0.91 to −0.20) | 0.65 (−4.57 to 5.88) | −0.90 (−1.41 to −0.39) | −0.25 (−4.40 to 3.90) |

| Poland | 2.70 (2.43 to 2.97) | 1.19 (−0.64 to 3.01) | 1.62 (1.28 to 1.97) | 1.28 (−0.85 to 3.42) |

| Denmark† | 0.60 (0.17 to 1.03) | −1.70 (−7.51 to 4.11) | −0.11 (−0.64 to 0.41) | −1.70 (−9.61 to 6.21) |

| Austria | 0.84 (0.40 to 1.28) | −0.06 (−1.17 to 1.04) | 0.29 (−0.11 to 0.69) | 2.17 (−7.11 to 11.5) |

| Belgium‡ | 2.10 (1.77 to 2.60) | −2.74 (−7.18 to 1.71) | 2.22 (1.74 to 2.84) | −1.17 (−5.74 to 3.41) |

| France‡ | 2.20 (2.03 to 2.37) | 1.96 (−1.60 to 5.51) | 1.23 (0.97 to 1.49) | 2.64 (−9.63 to 14.9) |

| The Netherlands | 2.54 (2.31 to 2.76) | 1.04 (−3.34 to 5.42) | 1.79 (1.48 to 2.10) | −0.82 (−6.33 to 4.69) |

| Switzerland‡ | 0.33 (−0.06 to 0.72) | 4.28 (−3.85 to 12.4) | −0.37 (−0.78 to 0.04) | −1.21 (−3.11 to 0.69) |

In bold, significant trends.

*Data available from 1986.

†Data available until 2011.

‡Data available until 2010.

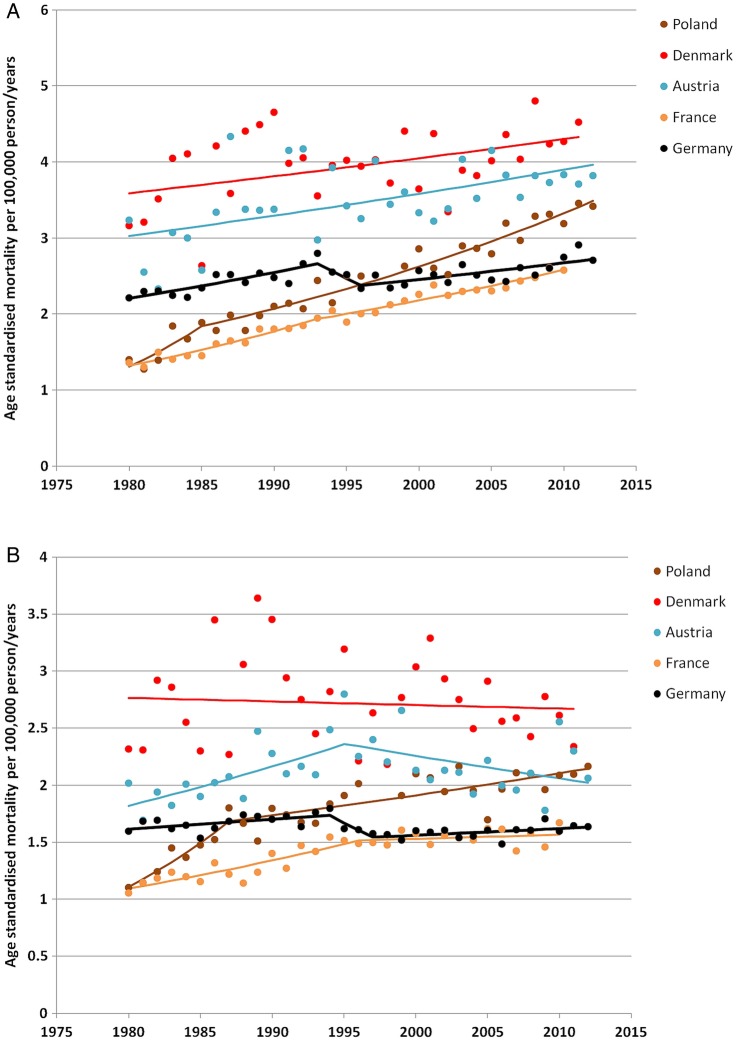

In the 5-year period following the introduction of the national screening programme, melanoma mortality rates increased by 2.60% in men and 0.02% in women. Hence, upward trends were more marked in the years after screening introduction than during the whole period. The joinpoint analysis did not identify a change in trends after 2008 that could have suggested some downward inflexion in mortality. The last inflexion in men was observed in 1996 followed by a monotonic significant increase in mortality of 0.8% (95% CI 0.4 to 1.3; figure 3). In women, the last downward inflexion was observed in 1997, also followed by a monotonic significant increase of 0.4% (95% CI 0.0 to 0.8).

Figure 3.

Trend in cutaneous melanoma mortality in Germany and surrounding countries in (A) men and (B) women. Data from the WHO mortality database (November 2014 release). Each dot represents the actual age-standardised rate for each country and year, and the corresponding regression lines were computed by the joinpoint model.

Comparison with surrounding countries

For men and women, trends in melanoma mortality in Germany did not differ from trends in surrounding countries (figure 3). No decline in melanoma mortality was observed in the surrounding countries, except in Austrian women in whom a decline of −0.9% per year (95% CI −1.8% to −0.0%) took place after 1994. Analysis of trends by age group (table 2) did not indicate any particular difference in most recent trends in Germany and in surrounding countries.

Table 2.

Melanoma mortality annual per cent change in the most recent uninterrupted trend identified by joinpoint regression by age group in Germany and surrounding countries

| Country | Below 60 years |

60–74 Years |

75 Years and above |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual per cent change % (95% CI) | Period | Annual per cent change % (95% CI) | Period | Annual per cent change % (95% CI) | Period | |

| Men | ||||||

| Germany | −0.9 (−1.2 to −0.7)↓ | 1980–2012 | 1.4 (0.6 to 2.1)↑ | 1998–2012 | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.1)↑ | 1992–2012 |

| Czech Republic* | −2.8 (−3.5 to −2.1)↓ | 1986–2012 | −0.3 (−0.9 to 0.4) | 1986–2012 | 2.1 (1.4 to 2.8)↑ | 1986–2012 |

| Poland | −0.4 (−1.6 to 0.7) | 1996–2012 | 3.1 (2.7 to 3.5)↑ | 1983–2012 | 5.6 (4.9 to 6.2)↑ | 1980–2012 |

| Denmark† | −1.2 (−1.8 to −0.6)↓ | 1980–2011 | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.2)↑ | 1980–2011 | 2.8 (1.6 to 4.1)↑ | 1980–2011 |

| Austria | −0.9 (−1.5 to −0.3)↓ | 1980–2012 | 1.1 (0.5 to 1.7)↑ | 1980–2012 | 1.5 (−0.3 to 3.3) | 1990–2012 |

| Belgium‡ | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.0)↑ | 1980–2010 | 2.3 (1.7 to 2.9)↑ | 1980–2010 | 1.7 (0.8 to 2.7)↑ | 1980–2010 |

| France‡ | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4)↑ | 1980–2010 | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.6)↑ | 1990–2010 | 3.4 (2.9 to 3.9)↑ | 1980–2010 |

| The Netherlands | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.5)↑ | 1980–2012 | 3.9 (3.5 to 4.4)↑ | 1980–2012 | 3.9 (3.2 to 4.7)↑ | 1980–2012 |

| Switzerland‡ | −1.3 (−2.1 to −0.6)↓ | 1980–2010 | 0.6 (−0.0 to 1.2) | 1980–2010 | 0.1 (−1.6 to 1.9) | 1991–2012 |

| Women | ||||||

| Germany | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.8) | 1997–2012 | −0.4 (−0.8 to −0.0)↓ | 1988–2012 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3)↑ | 1980–2012 |

| Czech Republic* | −2.2 (−3.0 to −1.4)↓ | 1986–2012 | −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.3) | 1986–2012 | 6.4 (−2.0 to 15.5) | 2007–2012 |

| Poland | −0.5 (−1.0 to −0.0)↓ | 1987–2012 | 2.0 (1.7 to 2.4)↑ | 1980–2012 | 3.5 (3.1 to 4.0)↑ | 1980–2012 |

| Denmark† | −1.7 (−2.5 to −0.8)↓ | 1980–2011 | 0.6 (−0.2 to 1.3) | 1980–2011 | 2.0 (1.4 to 2.6)↑ | 1980–2011 |

| Austria | −0.4 (−1.0 to 0.3) | 1980–2012 | 0.3 (−0.3 to 0.9) | 1980–2012 | −0.5 (−2.1 to 1.1) | 1994–2012 |

| Belgium‡ | 1.0 (0.1 to 2.0)↑ | 1988–2010 | 0.8 (−0.6 to 2.3) | 1988–2010 | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.0)↑ | 1980–2010 |

| France‡ | 0.5 (0.1 to 0.9)↑ | 1980–2010 | 0.4 (−0.7 to 1.4) | 1994–2010 | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.6)↑ | 1980–2010 |

| The Netherlands | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.6)↑ | 1980–2012 | 2.3 (1.7 to 2.9)↑ | 1980–2012 | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.3)↑ | 1980–2012 |

| Switzerland‡ | −1.4 (−2.0 to −0.8)↓ | 1980–2010 | 0.2 (−0.5 to 0.9) | 1980–2010 | 0.1 (−0.7 to 0.9) | 1982–2010 |

In bold, significant trends.

*Data available from 1986.

†Data available until 2011.

‡Data available until 2010.

↑Statistically significant increase of melanoma mortality.

↓Statistically significant decrease of melanoma mortality.

Discussion

The decline in melanoma mortality reported in the 5 years immediately following the start of the SCREEN project in Schleswig–Holstein was transient and during the next 5 years, rates returned to levels prevailing prior to the introduction of screening. Introduction of screening in Germany led to significant increases in the number of diagnoses of cutaneous melanoma similar to increases reported in Schleswig–Holstein after the introduction of the SCREEN project.2 In the German study, invasive melanoma diagnoses increased by 53% in women in Schleswig–Holstein with screening, compared with 18% in another city, Saarland, which had no screening. A similar effect was observed in men with a 26% increase in Schleswig–Holstein compared with 10% in Saarland.15 But contrary to Schleswig–Holstein where melanoma mortality decreased in the five years after introduction of screening, trends in melanoma mortality in the whole of Germany did not decrease in years following introduction of screening. In addition, mortality trends in Germany in recent years did not differ from those in surrounding countries.

There is currently no systematic comprehensive evaluation of the skin cancer screening programme in Germany. Data needed for a proper understanding of differences between the SCREEN project and the national screening programme are lacking. Several factors suggest that the national programme was more intense with a higher participation rate than in the SCREEN project, additional services offered by insurance companies and a continuous programme. In contrast, the screening period of the SCREEN project only lasted 12 months. In view of initial results of the SCREEN project, some decline in melanoma mortality for all of Germany should have been observed in the years immediately following the introduction of the national skin cancer screening programme. It could be argued that more years of observation are needed before an impact on melanoma mortality could show up. If the latter argument is considered valid, then the likelihood of the 48% reduction in melanoma mortality in 2003–2008 reported for Schleswig–Holstein is questionable: in fact, both mortality reduction and its association with screening are questionable. In addition, the return in 2012–2013 to melanoma mortality rates prevailing before the start of the screening campaign further questions the likelihood of the transient drop in mortality reported for Schleswig–Holstein. The issue of lead time is central to the interpretation of these data. It has been estimated that it would take at least 5–7 years for an effective screening programme to potentially decrease mortality.16 Additional elements raise scepticism about the likelihood of the SCREEN project results.7 17 For instance, a low 20% participation in screening and a high 48% reduction in melanoma mortality are hardly compatible. The decline in melanoma mortality actually started 2 years before the launch of the SCREEN project, which cast doubt on whether skin screening was the actual cause for mortality reductions.

The analysis of impact of skin cancer screening in Germany and in particular in Schleswig–Holstein would benefit from data on trends in melanoma incidence by stage. Unfortunately, such data are not systematically reported to cancer registries in Germany. Even in Schleswig–Holstein, covered by a cancer registry of good quality, a study between 2000 and 2008 showed that 69.5% of melanoma cases have an unknown Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) stage.18

In view of these elements, skin cancer screening is most probably not the cause of the transient reduction in melanoma mortality in Schleswig–Holstein, and the possible contribution of other factors needs to be evoked. A first possibility could be random variation in trends because of the relatively small number of melanoma deaths occurring each year in Schleswig–Holstein. For each sex, about 42 melanoma deaths per year were reported in Schleswig–Holstein,5 which resulted in important fluctuations in the estimation of mortality rate (figure 1).

Another possibility could be a bias in the ascertainment of the causes of death. Certifications of the causes of death in Germany are performed by physicians having their practice in the municipality where the postmortem examination takes place.19 Three-quarters of physicians established in Schleswig–Holstein with outpatient activities (including surgeons, gynaecologists, urologists) participated in the SCREEN project. The SCREEN project benefited from intense mass media coverage.4 Within this context, we hypothesise that doctors practising in Schleswig–Holstein would have under-reported melanoma as the underlying cause of death. Such a bias is very likely because the SCREEN project was not a randomised controlled trial with blinding of cause of death assessors for the screening status of subjects. In addition, doctors were the entry point of participants in the SCREEN project; they were entitled to perform TBSE, and they were motivated by a financial incentive for each TBSE.6 The combined effect of these factors could have contributed to inducing a systematic bias in the causes of death reported on death certificates.

Unbiased ascertainment of causes of death is a challenge in studies having death due to a specific disease as the principal outcome. Even randomised trials on cancer screening are not immune to ascertainment bias. For instance, in the Swedish trials on breast cancer screening, cause of death committees or doctors completing death certificates knew or could guess which women had been invited to screening. A still ongoing controversy is to know whether the absence of true blinding of cause of death assessors may have introduced bias in the results of these trials.20

Conclusion

The analysis of trends of melanoma mortality in Germany and in Schleswig–Holstein does not provide evidence that skin cancer screening is effective for preventing melanoma death. We hypothesise that a highly plausible reason for the transient decline in melanoma mortality reported in Schleswig–Holstein after screening start would be that the SCREEN project altered the way doctors reported the causes of death. If this hypothesis turned out to be grounded, then the German skin cancer screening programme would no longer be justified. The lack of a comprehensive evaluation is a major failure of the German screening programme.

Footnotes

Contributors: MB, PA and SG contributed to the conception of the study, as well as to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the manuscript. They drafted the manuscript and revised it critically. All the authors gave their final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among US adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med 2014;61:75–80. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breitbart EW, Waldmann A, Nolte S et al. Systematic skin cancer screening in Northern Germany. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;66:201–11. 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer 2012;106:970–4. 10.1038/bjc.2012.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anders MP, Nolte S, Waldmann A et al. The German SCREEN project—design and evaluation of the communication strategy. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:150–5. 10.1093/eurpub/cku047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katalinic A, Waldmann A, Weinstock MA et al. Does skin cancer screening save lives?: an observational study comparing trends in melanoma mortality in regions with and without screening. Cancer 2012;118:5395–402. 10.1002/cncr.27566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer JE, Swetter SM, Fu T et al. Screening, early detection, education, and trends for melanoma: current status (2007–2013) and future directions: Part II. Screening, education, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71:611.e1–10. 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geller AC, Greinert R, Sinclair C et al. A nationwide population-based skin cancer screening in Germany: proceedings of the first meeting of the International Task Force on Skin Cancer Screening and Prevention (September 24 and 25, 2009). Cancer Epidemiol 2010;34:355–8. 10.1016/j.canep.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisemann N, Waldmann A, Garbe C et al. Development of a microsimulation of melanoma mortality for evaluating the effectiveness of population-based skin cancer screening. Med Decis Making 2015;35:243–54. 10.1177/0272989X14543106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornek T, Schäfer I, Reusch M et al. Routine skin cancer screening in Germany: four years of experience from the dermatologists’ perspective. Dermatology 2012;225:289–93. 10.1159/000342374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. (GEKID). http://www.gekid.de (accessed 10 Dec 2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. www.gbe-bund.de (accessed 15 Dec 2014).

- 12.National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 3.5.4. Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute, August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19:335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breitbart EW, Choudhury K, Anders MP et al. Benefits and risks of skin cancer screening. Oncol Res Treat 2014;37(Suppl 3):38–47. 10.1159/000364887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debating Population vs. Genetic Screening for Melanoma. Oncology Times 2015;37:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etzioni R, Legler JM, Feuer EJ et al. Cancer surveillance series: interpreting trends in prostate cancer—part III: quantifying the link between population prostate-specific antigen testing and recent declines in prostate cancer mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:1033–9. 10.1093/jnci/91.12.1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.USSG. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General's call to action to prevent skin cancer. Washington DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2014. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/prevent-skin-cancer/ (accessed 15 Dec 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisemann N, Waldmann A, Katalinic A. Imputation of missing values of tumour stage in population-based cancer registration. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:129 10.1186/1471-2288-11-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das C. Death certificates in Germany, England, The Netherlands, Belgium and the USA. Eur J Health Law 2005;12:193–211. 10.1163/157180905774857916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen O, Gøtzsche PC. Cochrane review on screening for breast cancer with mammography. Lancet 2001;358:1340–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06449-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]