Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the multinational medical-student-delivered tobacco prevention programme for secondary schools for its effectiveness to reduce the smoking prevalence among adolescents aged 11–15 years in Germany at half year follow-up.

Setting

We used a prospective quasi-experimental study design with measurements at baseline (t1) and 6 months postintervention (t2) to investigate an intervention in 8 German secondary schools. The participants were split into intervention and control classes in the same schools and grades.

Participants

A total of 1474 eligible participants of both genders at the age of 11–15 years were involved within the survey for baseline assessment of which 1200 completed the questionnaire at 6-month follow-up (=longitudinal sample). The schools participated voluntarily. The inclusion criteria were age (10–15 years), grade (6–8) and school type (regular secondary schools).

Intervention

Two 60 min school-based modules delivered by medical students.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary end point was the difference from t1 to t2 of the smoking prevalence in the control group versus the difference from t1 to t2 in the intervention group (difference of differences approach). The percentage of former smokers and new smokers in the two groups were studied as secondary outcome measures.

Results

In the control group, the percentage of students who claimed to be smokers doubled from 4.2% (t1) to 8.1% (t2), whereas it remained almost the same in the intervention group (7.1% (t1) to 7.4% (t2); p=0.01). The likelihood of quitting smoking was almost six times higher in the intervention group (total of 67 smokers at t1; 27 (4.6%) and 7 (1.1%) in the control group; OR 5.63; 95% CI 2.01 to 15.79; p<0.01). However, no primary preventive effect was found.

Conclusions

We report a significant secondary preventive (smoking cessation) effect at 6-month follow-up. Long-term evaluation is planned.

Keywords: tobacco prevention, medical students, secondary schools, adolescents, school-based prevention, smoking cessation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

No medical-student-delivered school-based tobacco prevention programme has been evaluated for its preventive effect to date.

It is imperative to sensitise prospective physicians to tobacco prevention.

The quasi-experimental design of this study caused a selection bias due to the lack of randomisation.

Since control classes were located in the same schools, cluster effects could not be excluded entirely.

Our follow-up data were only collected 6 months after the intervention due to organisational reasons. Thus, we were not able to determine the long-term effects.

Background

Smoking is the biggest external cause of non-contagious disease and is responsible for more deaths than obesity both globally and in high income countries such as Germany or the USA.1 2

The 2011 European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs report revealed that a higher percentage of 16-year-old pupils from Germany claimed to have smoked in the past 30 days (33%) than pupils from Denmark (24%), Greece (21%) and Sweden (21%).3 Additionally, the use of water pipes has increased in the past few years in German adolescents and was described to have similarly deleterious effects on human health.4 5

A popular school-based tobacco prevention programme, which has been implemented in many countries in the European Union, is the Smoke-free Class Competition (called ‘Be Smart Don't Start’) in Germany.6–8 However, a Cochrane systematic review from 2012 concluded that this programme was not effective for primary or secondary smoking prevention in adolescents.8

Less popular secondary school programmes that involve physicians as health educators have already been evaluated showing significantly positive effects.9 10 However, they are not broadly available.

Recent studies from prestigious international and national medical faculties indicate that tobacco addiction is drastically undertreated by physicians in comparison with other chronic conditions, mainly because of lack of motivation, skills and knowledge.11–13 Novel ways of engagement of prospective physicians were demanded.11 A key advantage of the Education Against Tobacco (EAT) programme is that medical students learn to take tobacco-related responsibilities in their role as health educators in schools and to discuss tobacco-associated diseases in an understandable way. These aspects facilitate school-based prevention and also provide education for cooperative decision-making in inpatient settings.14 15 The multinational programme EAT is currently enrolled in over 40 medical schools in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Uruguay, Pakistan, Sudan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bangladesh and the USA.

The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of the school-based EAT intervention in smoking initiation prevention and smoking cessation in Germany.14 The primary end point was the difference from t1 to t2 of the smoking prevalence in the intervention group versus the difference from t1 to t2 in the control group (difference of differences approach).14 In addition, we aimed to assess whether the programme is equally effective for participants of different gender, social and cultural backgrounds.14

Methods

Design

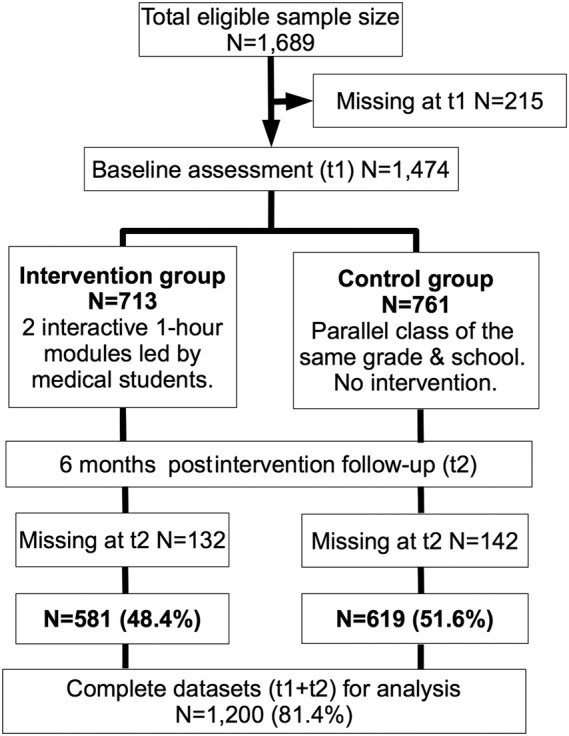

As defined in our protocol, the survey was designed as a quasi-experimental prospective evaluative study with two measurements (baseline and 6 months postintervention).14 The period of data collection was October 2013 to July 2014. Participants in the two study groups (intervention and control groups) were questioned up to 2 weeks in advance of the intervention (t1) and 6 months thereafter (t2; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

Randomisation was impossible as schools refused to participate when informed that intervention classes would be randomly externally selected. Thus, we asked the participating schools in advance to split their grades themselves into two class groups (intervention vs control classes) with the same performance levels (parallel classes). All intervention classes in our sample had parallel classes.

Participants

A total of 1689 eligible secondary school students from eight eligible schools were recruited from November 2012 to October 2013. All participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Students aged 10–15 years attending grades 6–8 of a secondary general, intermediate, grammar or comprehensive school were eligible.14 Baseline data of 1474 participants were collected from October 2013 to January 2014. Follow-up data were collected from April to July 2014. In total, 1200 participants provided data at both time points (t1+t2) that were used for analysis. The loss to follow-up effect was 18.6% (N=274; intervention group: 9.0%=132; control group: 9.6%=142).

Attrition analysis

The participants who dropped out at follow-up (t2) were analysed with logistic regression analysis and showed no systematic bias with regard to the interaction between study group and smoking status (p=0.19) or study group and gender (p=0.725) or study group and school type (p=0.082). However, it showed a systematic bias for study group and age (p=0.045; OR=0.709; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.99), meaning that significantly more young people dropped out of the intervention group versus the control group.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of two interactive 60 min modules. The first part was presented by 2–6 medical students and a patient with a tobacco-related disease to all pupils at the same time inside a large room within the school. It consisted of a PowerPoint (Microsoft; Redmond, Washington, USA) presentation in which the participants were encouraged to make their own well-informed decisions (social competence approach). The university hospital patient with a smoking-related disease was interviewed about his reasons for starting to smoke and the influence tobacco consumption had on his life. Again, the students were encouraged to ask the patient their own questions.

The second part took place in an interactive classroom setting in which two medical students (usually a man and a woman) tutored one class. As reported in our study protocol, both modules focused on educating adolescents about the strategies of the tobacco industry to influence their decision in a non-objective manner (social influence) and on peer pressure (social influence), decision-making and skills for coping with challenges in their life in a healthy way (social competence).14 The participants also discussed information relevant for their age group, for example, why non-smokers usually look more attractive, have more money to buy things, or succeed in sports. The programme focused on not scaring but educating its participants in an interactive manner. Accordingly, EAT used a combined social influence and social competence approach, which has been described as the most effective approach in the recently published Cochrane review.14 16

Data collection

We used a paper-and-pencil survey questionnaire that was developed to collect data in the classroom via the class teachers at both time points (t1 and t2).14 In addition to the sociodemographic data (age, gender, school type), it captured the smoking status of the school students concerning water pipe use and cigarette consumption.

The questionnaire contained numerous items that have already been included in similar investigations. The questions about the smoking status and the frequency of smoking referred to the evaluation of the school-based smoking prevention programmes in Heidelberg titled ‘ohne kippe’ (no butts) and in Berlin titled ‘Students in the Hospital’, as well as to the results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents published by Lampert and Thamm.10 17 18 As described in our study protocol, we tested and optimised the questionnaire in accordance with the Good Epidemiologic Practice guidelines.19

The class teachers individually supervised their classes during the completion of the questionnaire. To maximise the confidentiality of the intervention, the questionnaires were placed in envelopes that were instantly sealed and cosigned by the responsible class teachers immediately after completion. The envelopes were shipped to the Goethe University of Frankfurt where they were opened and the data entry and analysis was performed under the supervision of two of the authors (DAG and DK).

Outcomes

The primary end point was the difference from t1 to t2 of the smoking prevalence in the control group versus the difference from t1 to t2 in the intervention group (difference of differences approach). The percentages of former smokers and new smokers in the two groups were studied as secondary outcome measures. A smoker was defined as a pupil who claimed to smoke at least ‘once a month’ within the survey. Non-smokers were defined as pupils who claimed to smoke less than ‘once a month’ within the survey.

Statistical analysis

To examine baseline differences, we used χ2 tests (categorical variables) and Student t tests (continuous variables). The effects of predictors (gender, culture and social characteristics) of smoking cessation were calculated by robust panel logistic regression analysis. The significance level was 5% for Student t tests (double-sided) and 95% for CIs (double-sided). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics V.23 by IBM (Armonk, USA) and STATA 14 by StataCorp (Texas, USA). In our sample, the group allocation was not on the individual level but on the class level. In order to take into account this clustering statistically, we used robust panel logistic regression (xtlogit procedure with vce(cluster) option). This procedure was also used to calculate the difference from t1 to t2 of the smoking prevalence in the control group versus the difference from t1 to t2 in the intervention group (our primary end point) with the help of STATA 14 by StataCorp (Texas, USA).

Legal approval

In accordance with Good Epidemiologic Practice guidelines, an ethics waiver and all legal permissions were obtained from the responsible institutions before data collection started as described in our study protocol.14 19

Results

Baseline data

The median age of the 1474 eligible participants at baseline (figure 1) was 13 years (mean age 12.55 years; range 11–15 years) and 52% were female. Of the participants, 43.9% attended grammar schools and the remaining 56.1% attended comprehensive schools (which were classified in the survey as ‘lower education level’). The survey identified 6.4% of participants as smokers at baseline. There were no significant differences concerning the number of smokers in both groups (p=0.088; table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive data at baseline

| Variables | Intervention group (N=713) | Control group (N=761) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 349 (49.5) | 352 (46.6) | 0.261 |

| Female | 356 (50.5) | 404 (53.4) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean (±SD) | 12.47 (0.79) | 12.64 (0.78) | <0.01 |

| School type, n (%) | |||

| Grammar | 281 (39.4) | 366 (48.1) | <0.01/0.046* |

| Comprehensive | 432 (60.6) | 395 (51.9) | |

| Migrant background, n (%) | 182 (27.5) | 221 (31.3) | 0.122 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Smokers | 54 (7.6) | 41 (5.4) | 0.088 |

| Non-smokers | 659 (92.4) | 720 (94.6) | |

| Smoking behaviour of non-smokers, n (%) | |||

| Never smoked | 615 (95.1) | 683 (97.0) | |

| Stopped less than 6 months beforehand | 9 (1.4) | 12 (1.7) | 0.021 |

| Stopped more than 6 months beforehand | 23 (3.6) | 9 (1.3) | |

| Smoking behaviour of smokers, n (%) | |||

| Cigarettes (monthly-daily) | 32 (60.4) | 21 (39.6) | 0.435 |

| Daily | 8 (25.0) | 4 (19.1) | 0.613 |

| More than once per week | 2 (6.3) | 2 (9.5) | 0.659 |

| Once per week | 4 (12.5) | 3 (14.3) | 0.851 |

| Monthly | 18 (56.3) | 12 (57.1) | 0.683 |

| Water pipe smokers (monthly-daily) | 34 (58.6) | 24 (41.4) | 0.661 |

| Daily | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 0.135 |

| More than once per week | 6 (17.7) | 3 (12.5) | 0.594 |

| Once per week | 5 (14.7) | 2 (8.3) | 0.463 |

| Monthly | 20 (58.8) | 19 (79.2) | 0.104 |

*p Value adjusted for class size (classes in the intervention group were systematically smaller than in the control group (mean class size=23.96 vs 25.07 in the control group; p<0.01)).

Follow-up at 6 months

Analyses of the data were by original assigned groups: There were 581 pupils in the intervention group and 619 pupils in the control group who had participated in the survey at both time points (baseline sample=1474 pupils; prospective sample=1200 pupils; loss to follow-up=274 pupils).

Primary end point

There was a significant effect for the defined primary end point (OR 0.35; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.78; p=0.01) calculated with the prospective sample of 1200 participants (table 2): The percentage of students who claimed to be smokers doubled from 4.2% (t1) to 8.1% (t2) in the control group, whereas it remained almost the same in the intervention group (7.1% (t1) to 7.4% (t2)). The development in terms of smoking prevalence of the two study groups was significantly different (p=0.01; table 2).

Table 2.

Primary end point calculated by robust panel logistic regression (xtlogit procedure with vce(cluster) option)

| Variable | SE | p Value | OR | 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| time#group#endline#intervention group* | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.78 |

*Difference in smoking prevalence from t1 to t2 of the smoking prevalence in the control group versus the difference from t1 to t2 in the intervention group (see Methods section).

Secondary outcomes

At 6-month follow-up, 27 (4.6%) smokers in the intervention group had quit but only 7 (1.1%) smokers in the control group were abstinent (table 3). However, no primary preventive (initiation prevention) effect was found as in both groups 5.0% of the prospective sample started to smoke (table 3).

Table 3.

Nominal and percentage effects of the intervention on the smoking status (secondary outcomes)

| Prospective smoking status (t1–t2) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stays a non-smoker | Starts smoking | Stops smoking | Stays a smoker | |

| Control group | ||||

| N | 562 | 31 | 7 | 19 |

| Percentage in group | 90.8 | 5.0 | 1.1 | 3.1 |

| Intervention group | ||||

| N | 511 | 29 | 27 | 14 |

| Percentage in group | 88.0 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 2.4 |

| Total | ||||

| N | 1073 | 60 | 34 | 33 |

| Percentage in group | 89.4 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

Predictors of smoking cessation

The likelihood of quitting smoking was more than five times higher in the intervention group according to robust panel logistic regression analysis (OR 5.63; 95% CI 2.01 to 15.79; p<0.01; table 4). As can also be seen in table 4, age seems to have a significant effect on smoking status: increasing the age by 1 year within our sample (11–15 years) reduces the likelihood to stop smoking by 61% (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.78). Students from comprehensive school within our prospective sample have a 60% lower likelihood of quitting smoking when compared with students from grammar schools (OR 0.40; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.91; p=0.03).

Table 4.

Robust panel logistic regression analysis (main effects) for prediction of quitting smoking by smokers (n=67)

| Variables | Robust SE | p Value | OR | 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | 0.14 | <0.01 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.78 |

| Gender (ref. female) | 0.74 | 0.64 | 1.31 | 0.43 | 3.98 |

| Intervention group (ref. control) | 2.96 | <0.01 | 5.63 | 2.01 | 15.79 |

| Comprehensive school (ref. grammar school) | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.91 |

Since the sample sizes for smokers in the intervention group were relatively small, we cannot prove a systematic co-dependency between quitting smoking and migrant background or gender.

Discussion

School-based physician-delivered tobacco prevention programmes have shown short-term and long-term effectiveness but are usually expensive and tutor relatively few students.9 10 20 At the same time, it is imperative to sensitise prospective physicians to tobacco addiction and associated responsibilities within communities.21 22 In this study, we report a significant effect to reduce smoking prevalence of a widespread intervention delivered by volunteer medical students to secondary school students (11–15 years); at 6 months of follow-up, the OR was 5.63 to stop smoking in the intervention versus the control group (CI 2.01 to 15.79; p<0.01). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first evaluation of a medical-student-delivered school-based tobacco intervention.

Interpretation

Our data reveal that motivating students to quit smoking using EAT works significantly better at a young age (p<0.01), which suggests that younger smokers are not as addicted as older smokers but are more likely to be in the phase of experimentation. Accordingly, most of the smoking participants in the survey claimed to smoke less than once a day. The participants who started smoking also showed experimentation characteristics (most of them smoking less than once a day). Thus, we hypothesise that in this young age group it may be more difficult to reduce curiosity and to avoid experimentation behaviour in the short term than it is to convince those who have already experimented with cigarettes to stop smoking. This hypothesis is supported by numerous publications addressing this age group, which show no primary preventive effect at half year follow-up with various approaches.16 Another explanation for the short-term result of no primary prevention effect can be found within the recent Cochrane review: combined social competence and social influence programmes such as EAT did not show primary preventive effectiveness at less than 1 year follow-up within the meta analysis.16 Thus, our intervention might also show a primary preventive effect at longer follow-up. In addition, we hypothesise that the effect on reducing smoking prevalence in the intervention group would have been larger in a randomised experimental setting as we found two biases both potentially shrinking the effect of the intervention (see below).

The implementation of cost-effective measures to prevent smoking in adolescents and, moreover, the sensitisation of prospective physicians to tobacco-attributable diseases, tobacco prevention and improved communication of these issues in medicine is addressed by our programme.11 12 13 15

Limitations

Our data indicate that the quasi-experimental design of our study caused some selection bias as the number of smokers (7.6% vs 5.4%) and former smokers (5% vs 3%) was higher in the intervention group in the complete baseline sample (cross-sectional data). The teachers probably insisted on choosing classes at higher risk for smoking as intervention classes, which is also illustrated by a significantly higher number of pupils visiting classes with a lower education level within the intervention group (p<0.01), as smoking correlates with low education.9 Accordingly, our robust panel logistic regression analysis on our prospective smoker subgroup revealed that students from comprehensive schools have a significantly lower likelihood of quitting smoking (p=0.03). Since young age is also a significant predictor of quitting in our sample (p<0.01), the reported attrition bias showing that systematically more young students dropped out in our intervention group (p=0.045) might have lowered the effect of the intervention. Thus, we report two systemic biases in our quasi-experimental design considering age (attrition bias; p=0.045) and school type (selection bias; significantly more comprehensive school students and less grammar school students in our intervention group at baseline; p<0.01), both of which rather decrease the measured effect in reducing smoking prevalence of the intervention. In addition, cluster effects could not be excluded because the intervention and control groups attended the same schools.

Our study relies on self-reports obtained from adolescents via questionnaire; therefore, there is a risk that the actual prevalence of smoking may be different from the reported prevalence, possibly because of social desirability bias. This bias could only be excluded by using expensive methods such as testing for cotinine (a metabolite of nicotine) in the saliva, blood or urine of the students. However, recent publications indicate that self-reports via questionnaire are relatively precise in tobacco research excluding pregnant women and patients with tobacco-related diseases.23

Generalisation

The participants came from the two most prevalent German school types (comprehensive and grammar schools), which makes our results transferable to the majority of German students in the age group 11–15 years. However, since our research is not multinational, our results might not be transferable to other countries.

Dissemination of the intervention

About 3 years after medical student TJB founded EAT (January 2012), the programme has more participating mentors (800 medical students) and interactively educates more secondary school students (20 000) per year than any other known school-based physician-delivered or medical-student-delivered tobacco prevention programme in Germany or, as far we know, worldwide. It is enrolled in over 40 medical schools in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Uruguay, Pakistan, Sudan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bangladesh and the USA. It currently costs about €20 per participating class and is therefore less expensive than comparable programmes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the EAT programme significantly reduces smoking prevalence in secondary school students at 6 months of follow-up (OR 0.35; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.78; p=0.01). Thus, medical students can effectively be involved in school-based tobacco prevention programmes. Further research and long-term evaluation are needed to confirm this post hoc finding. The EAT curriculum will be optimised by the implementation of a photoaging mobile app, which we plan to report on in further investigations.24

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the volunteer medical students Hannes Tabert, Svea Holtz, Stefan Henkel, Laura Schwab, Thorben Sämann, Andreas Owczarek, Felix Neumann, Anika Wolf, Felix Hofmann and Lorena Steinbach for their strong engagement within the EAT programme which made the relatively large sample size possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: TJB contributed to the design and conduct of the study, invented, designed and organised the intervention, wrote the manuscript, coordinated and conducted data entry and performed the statistical analysis. DAG contributed to the design of the study, monitored the data entry and proofread the manuscript. SS-B contributed to the design of the study and the analysis of data and proofread the manuscript. WS advised us on the conduction of the survey and on the collaboration with the schools and proofread the manuscript. DK supported the conduction of data entry and proofread the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript. This study is part of a thesis project (TJB).

Funding: Each participating school paid a small fee for the copies of the questionnaire that were distributed to every participating student.

Competing interests: TJB holds a Kaltenbach-scholarship and a grant on tobacco research from the German Heart Foundation.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee at the Goethe-University in Frankfurt sent us an ethics waiver as this was no biomedical experiment involving human materials.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 2011;377:557–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mons U. [Tobacco-attributable mortality in Germany and in the German Federal States—calculations with data from a microcensus and mortality statistics]. Gesundheitswesen 2011;73:238–46. 10.1055/s-0030-1252039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Björn Hibell UG, Ahlström S, Balakireva O et al. The 2011 ESPAD Report: substance use among students in 36 European Countries. 2011.

- 4.German Federal Center for Health Education (BZgA). Die Drogenaffinität Jugendlicher in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2011. In: Teilband Rauchen (Bericht) 2012. http://drogenbeauftragte.de/fileadmin/dateien-dba/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/Pressemitteil ungen_2012/Drogenaffinitaetsstudie_BZgA_2011.pdf

- 5.Maziak W. The global epidemic of waterpipe smoking. Addict Behav 2011;36:1–5. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isensee B, Morgenstern M, Stoolmiller M et al. Effects of Smokefree Class Competition 1year after the end of intervention: a cluster randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:334–41. 10.1136/jech.2009.107490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeflmayr D, Hanewinkel R. Do school-based tobacco prevention programmes pay off? The cost-effectiveness of the ‘Smoke-free Class Competition’. Public Health 2008;122:34–41. 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston V, Liberato S, Thomas D. Incentives for preventing smoking in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(10):CD008645 10.1002/14651858.CD008645.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sack P-M, Hampel J, Bröning S et al. Was limitiert schulische Tabakprävention? Prävention Gesundheitsförderung 2013;8:246–51. 10.1007/s11553-013-0388-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamm-Balderjahn S, Groneberg DA, Kusma B et al. Smoking prevention in school students: positive effects of a hospital-based intervention. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012;109:746–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein SL, Yu S, Post LA et al. Undertreatment of tobacco use relative to other chronic conditions. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e59–65. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raupach T, Falk J, Vangeli E et al. Structured smoking cessation training for health professionals on cardiology wards: a prospective study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012;21:915–22. 10.1177/2047487312462803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anders S, Strobel L, Krampe H et al. [Do final-year medical students know enough about the treatment of alcohol use disorders and smoking?]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2013;138:23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinker TJ, Stamm-Balderjahn S, Seeger W et al. Education Against Tobacco (EAT): a quasi-experimental prospective evaluation of a programme for preventing smoking in secondary schools delivered by medical students: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004909 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ 2003;327:745–8. 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas RE, McLellan J, Perera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(4):CD001293 10.1002/14651858.CD001293.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maier B, Bau AM, James J et al. Methods for evaluation of health promotion programmes. Smoking prevention and obesity prevention for children and adolescents. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:980–6. 10.1007/s00103-007-0302-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampert T, Thamm M. [Consumption of tobacco, alcohol and drugs among adolescents in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:600–8. 10.1007/s00103-007-0221-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.2004. Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Epidemiologie: Leitlinien und Empfehlungen zur Sicherung von Guter Epidemiologischer Praxis (GEP). BMBF Gesundheitsforschung. http://wwwgesundheitsforschung-bmbfde/_media/Empfehlungen_GEPpdf.

- 20.Scholz M, Kaltenbach M. [Promoting non-smoking behavior in 13-year-old students in primary schools and high schools. A prospective, randomized intervention study with 1,956 students]. Gesundheitswesen 2000;62:78–85. 10.1055/s-2000-10412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strobel L, Schneider NK, Krampe H et al. German medical students lack knowledge of how to treat smoking and problem drinking. Addiction 2012;107:1878–82. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Twardella D, Brenner H. Lack of training as a central barrier to the promotion of smoking cessation: a survey among general practitioners in Germany. Eur J Public Health 2005;15:140–5. 10.1093/eurpub/cki123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kentala J, Utriainen P, Pahkala K et al. Verification of adolescent self-reported smoking. Addict Behav 2004;29:405–11. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brinker TJ, Seeger W. Photoaging Mobile Apps: A Novel Opportunity for Smoking Cessation? J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]