Abstract

Objective

Some researchers have reported that distribution of total depressive symptom scores in the general population may follow an exponential pattern except at the lowest end of the scores. To understand the mechanism responsible for this phenomenon, we investigated the mathematical patterns of the individual distributions for each item of a depressive symptom scale.

Methods

We analysed data from 32 022 participants in the general population who participated in the Active Survey of Health and Welfare, Japan. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Japanese version of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). CES-D has 20 items, each of which is scored in 4 grades: ‘Rarely’, ‘Some’, ‘Much’ and ‘Most of the time’.

Results

The individual distributions of 16 negative items belonging to the depressive mood, somatic symptoms and retarded activities, and interpersonal relations categories, followed a common mathematical pattern, which displayed different distributions with a boundary at ‘Some’. The distributions for the 16 items between ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’ appeared to cross at a single point. On the other hand, the distributions of the 16 items between ‘Some’ and ‘Most’ followed a linear pattern when plotted using a log-normal scale. The remaining 4 items in the positive affect subscale showed non-specific patterns.

Conclusions

The common mathematical pattern of the 16 negative item distributions may contribute to the exponential pattern of the distribution of total depressive symptom scores except at the lowest end of the scores.

Keywords: STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first mathematical model analysis of the individual distributions for each item response of a self-reported depression scale.

A large representative sample of the Japanese general population was used.

We found the distributions of the 16 negative items exhibited a common mathematical distribution.

Analysis based on other mathematical models was not performed.

Introduction

Depression is a common mental disorder that is among the leading causes of disability worldwide.1 Given that depressive symptoms are closely linked with depression, there has been great interest in understanding the distribution of depressive symptoms in the general population.2–4

Recently, we reported that the right tail of the distribution of total depressive symptom scores based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scales (CES-D) followed an exponential curve in the general population.5 In accordance with our results, Melzer et al6 reported that an exponential curve provided the best fit for total neurotic symptoms and depressive scores from the British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. Thus far, the potential mechanisms contributing to the specific pattern of the total depressive symptoms distribution have not been examined.

Of note, both Melzer et al and our group have pointed out that total depressive symptom scores follow an exponential curve over a specific level of depressive symptom scores. Melzer et al reported that all neurotic symptoms and depressive scores using the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) follow an exponential curve for symptom counts of more than 3. We reported that total depressive symptom scores follow an exponential curve in the range of CES-D scores over 11 points. These results indicate that the distributions of total depressive symptom scores differ according to the level of the total depressive symptom scores. The key to understanding the exponential curve of the total depressive symptom scores may lie in the different patterns of the distribution according to the levels of depressive symptom scores.

Depressive symptom scales consist of each item of the questionnaires. It has been hypothesised that the distributions of the responses for each item contribute to the different patterns of total depressive symptom score distributions. However, to our knowledge, little is known about the mathematical pattern of each item response in depressive symptom scales.

The CES-D is a 20-item self-reported scale that has been shown to measure depressive symptoms across four domains: depressed affects, somatic symptoms, positive affects and interpersonal difficulties.7 These four factors have been replicated in several populations and confirmed using meta-analytic methods.8–10

The present study examined the distributions of 20 depressive symptom items according to four factors using more than 30 000 CES-D assessments. The goal of the present study was to delineate the distribution patterns for each depressive symptom item and to examine whether the distributions of responses to each item contributed to the different patterns of the distributions according to the level of total depressive symptom scores.

Methods

Participants

We used data from the Active Survey of Health and Welfare (ASHW) conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, in 2000. The ASHW is an annual nationwide survey conducted to obtain data required for policy making by the Japanese Government. In 2000, the ASHW examined depressive symptoms among a representative sample of the Japanese general population. To ensure that the sample was representative of the general population, survey participants were selected from among individuals aged 12 years and over living in 300 communities across Japan. These communities were selected from 881 851 precincts identified in the 1995 census using a stratified sampling design. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The data and methods used by the survey have been publicised in detail.11

The questionnaire was returned by 32 729 respondents. The response rate was not published by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and Health. However, the response rates for similar surveys conducted 3 and 4 years earlier were 87.1% and 89.6%.12 We assumed that the response rate for the present study was over 80%. A total of 707 participants who returned a blank questionnaire were excluded from the analysis. The final sample size was 32 022.

Measures

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Japanese version of the CES-D. This 20-item scale assesses the frequency of a variety of depressive symptoms within the previous week (0=rarely or none of the time, 1=some of the time, 2=much of the time and 3=most or all of the time). Higher values indicate greater psychological distress. The 20 items of the CES-D were grouped into the following four subscales: depressive mood (items 3, 6, 9, 10, 14, 17 and 18), somatic and retarded activities symptoms (items 1, 2, 5, 7, 11, 13 and 20), interpersonal relations (items 15 and 19) and positive affects (items 4, 8, 12 and 16). The positive affect items were reverse scored (as shown in table 2).

Table 2.

Item responses of participants

| Number | Item/subscale | Response (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood | Rarely | Some | Much | Most | |

| 3 | Blues | 20 016 (72.3) | 5224 (18.9) | 1610 (5.8) | 820 (3.0) |

| 6 | Depressed | 15 673 (56.1) | 7839 (28.1) | 2899 (10.4) | 1511 (5.4) |

| 9 | Failure | 15 525 (55.6) | 7919 (28.3) | 3236 (11.6) | 1280 (4.6) |

| 10 | Fearful | 22 515 (80.7) | 3646 (13.1) | 1165 (4.2) | 565 (2.0) |

| 14 | Lonely | 21 818 (78.1) | 3917 (14.0) | 1398 (5.0) | 797 (2.9) |

| 17 | Crying | 25 420 (91.5) | 1653 (6.0) | 481 (1.7) | 227 (0.8) |

| 18 | Sad | 20 595 (74.0) | 5358 (19.2) | 1327 (4.8) | 568 (2.0) |

| Somatic symptoms and retarded activities | |||||

| 1 | Bothered | 14 970 (52.8) | 9683 (34.2) | 2852 (10.1) | 840 (3.0) |

| 2 | Appetite | 20 481 (71.9) | 5606 (19.7) | 1896 (6.7) | 498 (1.7) |

| 5 | Trouble concentrating | 14 985 (53.7) | 8614 (30.8) | 3216 (11.5) | 1109 (4.0) |

| 7 | Effort | 13 255 (47.1) | 10 078 (35.8) | 3149 (11.2) | 1656 (5.9) |

| 11 | Sleep | 17 789 (62.8) | 6555 (23.1) | 2687 (9.5) | 1301 (4.6) |

| 13 | Talked | 18 573 (66.7) | 6136 (22.0) | 2147 (7.7) | 972 (3.5) |

| 20 | Get going | 20 132 (72.5) | 5434 (19.6) | 1405 (5.1) | 813 (2.9) |

| Interpersonal relations | |||||

| 15 | Unfriendly | 22 616 (81.5) | 3636 (13.1) | 1030 (3.7) | 475 (1.7) |

| 19 | Dislike | 23 016 (82.6) | 3754 (13.5) | 760 (2.7) | 351 (1.3) |

| Positive affects | |||||

| 4 | Good | 9403 (36.1) | 5580 (21.4) | 3683 (14.2) | 7358 (28.3) |

| 8 | Hopeful | 8341 (36.0) | 8068 (29.6) | 5453 (20.0) | 5430 (19.9) |

| 12 | Happy | 9054 (32.6) | 8518 (30.6) | 4397 (15.8) | 5836 (21.0) |

| 16 | Enjoyed | 6561 (23.7) | 7028 (25.4) | 6903 (25.0) | 7136 (25.8) |

Analysis procedure

The item response percentages were delineated according to the depressive mood subscale, the somatic and retarded activities subscale, the interpersonal subscale and the positive affect subscale. The response rate for each item varied from 81.3% to 89.0%. Participants who did not respond to each item were excluded from the percentage analysis. The item response percentages for the distributions of the 20 items were analysed using a normal scale and a log-normal scale.

We used the JMP V.11 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) to calculate the descriptive statistics and the frequency distribution curves.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in table 1. Participants who did not respond to items regarding sex or age (n=222) were also included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Number of participants by gender and age group (N=32 022)

| Age group | Total (%) | Male (%) | Female (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12–19 | 3086 (9.6) | 1617 (10.6) | 1469 (8.9) |

| 20–29 | 4642 (14.5) | 2241 (14.7) | 2400 (14.5) |

| 30–39 | 4699 (14.7) | 2262 (14.9) | 2434 (14.7) |

| 40–49 | 4889 (15.3) | 2397 (15.8) | 2488 (15.0) |

| 50–59 | 5630 (17.6) | 2710 (17.8) | 2914 (17.6) |

| 60–69 | 4679 (14.6) | 2252 (14.8) | 2424 (14.6) |

| 70–79 | 3054 (9.5) | 1354 (8.9) | 1697 (10.2) |

| 80 or over | 1145 (3.6) | 383 (2.5) | 758 (4.6) |

| Total | 32 022 (100.0) | 15 217 (100.0) | 16 597 (100.0) |

Table 2 shows the response rates for the 20 items in the CES-D questionnaire. The items in the depressive mood group, the somatic symptoms and retarded activities group, and the interpersonal relations group, exhibited a common pattern, with a highest response frequency for ‘Rarely’ and a decreasing response frequency as the item score increased, with the lowest response frequency observed for ‘Most’. No exceptions to this pattern were seen. On the other hand, the four items in the positive affect subscale did not exhibit a similar pattern.

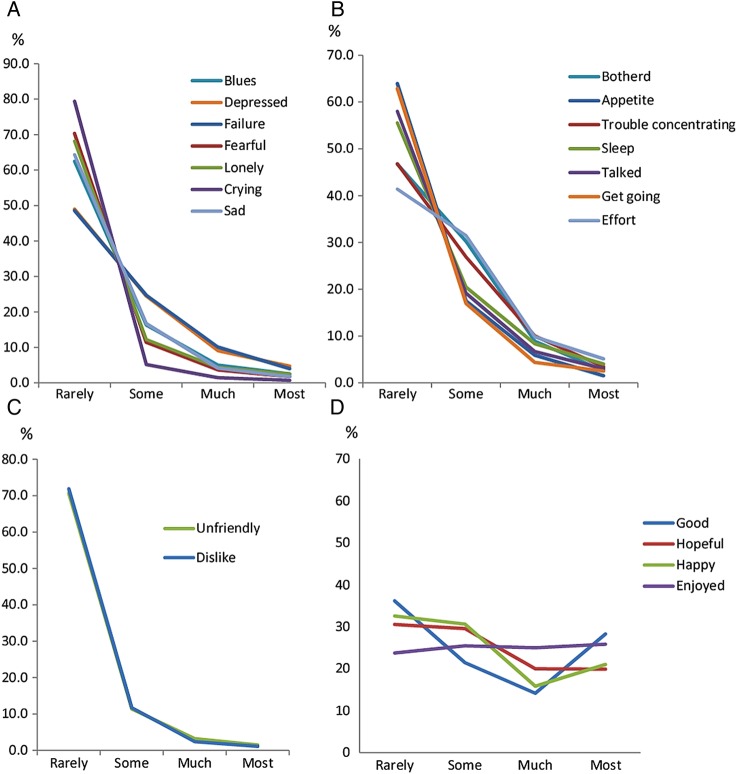

As depicted in figure 1, the depressive mood subscale (figure 1A), the somatic symptoms and retarded activities subscale (figure 1B), and the interpersonal relations subscale (figure 1C), exhibited right-skewed distributions, whereas the four items in the positive affect subscale (figure 1D) showed a plateau-shaped distribution, suggesting that the distribution pattern of the positive affect subscale differed from that of the other groups.

Figure 1.

Distributions of item responses for the depressive mood group (A), the somatic symptoms and retarded activities group (B), the interpersonal relations group (C) and the positive affect group (D). The (C) appears as one line, because two lines are close.

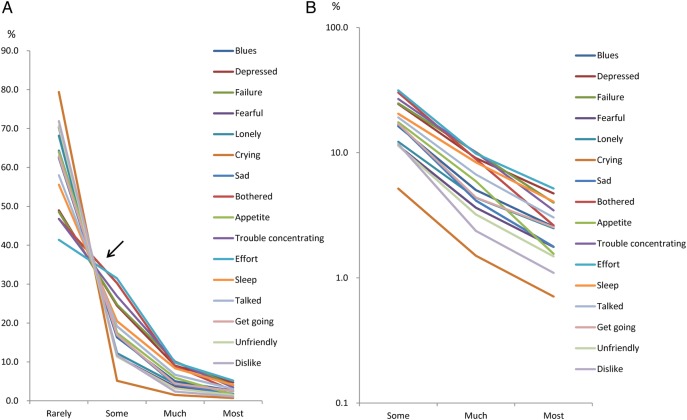

To ascertain the distribution pattern of each response for the 16 items in the depressive mood subscale, the somatic symptoms and retarded activities subscale, and the interpersonal relations subscale, the responses were plotted together. The distributions for each of the 16 items showed a common pattern, which displays different distributions with a boundary at ‘Some’ (figure 2A). The word ‘boundary’ refers to that which divides one mathematical pattern from another. The lines for the 16 items crossed with each other between ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’, whereas the lines rarely crossed between ‘Some’ and ‘Most’. As indicated by the arrow, the lines for all 16 negative items between ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’ appeared to cross at a single point. The distributions of the 16 items from ‘Some’ to ‘Most’ showed a characteristic pattern.

Figure 2.

The tails of the distributions of the 16 negative items are compared using a normal scale (A) and a log-normal scale (B).

With a log-normal scale, the distributions for the 16 items showed a linear pattern for the ‘Some’ to ‘Most’ responses (figure 2B), suggesting that these 16 items exhibited an exponential pattern for this response level. In addition, the lines for the 16 items were almost parallel to each other, suggesting that the gradients of the linear patterns for the 16 items were similar to each other.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to delineate the distributions of the responses to each depressive symptoms item and to examine whether the distributions of these item responses contributed to the different distribution patterns observed according to the level of total depressive symptom scores.

The main finding in the present study is that the distributions of the 16 items belonging to the depressive mood subscale, the somatic symptoms and retarded activities subscale, and the interpersonal subscale, follow a common mathematical model, which displayed different patterns with a boundary at ‘Some’. The lines for the 16 items appeared to cross at a single point between ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’, whereas the distributions of the 16 items between ‘Some’ and ‘Most’ followed an exponential pattern with the same parameter.

To confirm the reproducibility of these findings, we examined other published studies with various populations13–16 and confirmed this phenomenon in other studies, although the degree of fit to the mathematical model varied according to the studies (data not shown). These results, together with those of the present studies, suggest that the 16 negative items could follow the same distribution model in various populations.

The mechanism responsible for the exponential pattern of the total CES-D score except at the lowest end of the symptom score could be hypothesised based on the aforementioned findings as follows. Since the distributions of the positive affects items exhibited plateau-shaped patterns, the percentage of the positive affects score relative to the total depressive symptoms score would decrease with an increasing total CES-D score. Thus, the influence of the 16 negative items on the total CES-D score increases as the total CES-D score increases. Since the 16 negative items exhibited exponential patterns between the ‘Some’ and ‘Most’ response levels, the total CES-D score may follow an exponential curve over this range of specific CES-D scores. In addition, the similar exponential parameters of the 16 negative items might also contribute to the distribution of total CES-D score. Since the total CES-D score consists of each item of the questionnaires, and the responses to each item are inter-related to each other, it has been hypothesised that the inter-relations of the responses for each item contribute to the distribution of total CES-D score. However, the inter-relations of the responses for each item are complicated.8–10 Further evaluations using numerical expressions or simulation analyses are needed.

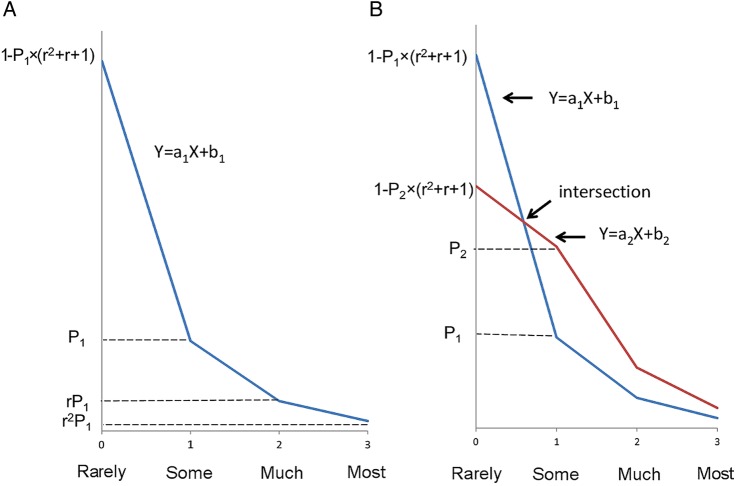

Mathematical model and crossing at a single point between ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’

The mathematical model that the 16 negative items follow is shown in figure 3A. If the probability of ‘Some’ is represented as P1 and the equal ratio among ‘Some’, ‘Much’ and ‘Most’ is represented as r. The probabilities of ‘Some’, ‘Much’, ‘Most’ and ‘Rarely’ are expressed as P1, P1r, P1r2 and 1−P1×(r2+r+1). The scores of ‘Rarely’, ‘Some’, ‘Much’ and ‘Most’ are expressed as 0, 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 3.

Distribution model of the items following an exponential pattern with the same parameter from ‘Some’ to ‘Most’ (A). Intersection of two lines (B).

In the present study, the lines for the 16 negative items appeared to cross together at a single point between the ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’ response levels (figure 2A). This finding can be explained by the mathematical model. As shown in figure 3A, the line between ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’ is expressed as:

where a1 is the gradient and b1 the intercept of the line.

Then a1 and b1 can be expressed as follows:

and

As shown in figure 3B, the two lines between ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’ are expressed as follows:

and

where,

and

The point where the two lines intersect can then be obtained as follows:

and

The intersection point is expressed by r only. Therefore, regardless of the slope and intercept of the line, all the lines that follow this mathematical model must cross at a single point between ‘Rarely’ and ‘Some’.

Recently, an item-response theory, developed in the field of education, has been used to evaluate the depressive symptom scales.17 18 In general, item-response theory assumes that a normally distributed latent trait underlies performance in a measure. However, to the best of our knowledge, no evidence for a normally distributed latent trait of depressive symptoms has been reported. Our results suggest the possibility that the distribution of latent traits of depressive symptoms could be exponential.

The reason why the distributions of the 16 negative items between ‘Some’ and ‘Most’ followed an exponential pattern is not clear. In general, exponential distribution is observed where individual variability and total stability are organised together, such as the Boltzmann-Gibbs law and income distribution.19 The Boltzmann formula shows the relationship between entropy and the number of ways the molecules of a thermodynamic system can be arranged. From the view point of the Boltzmann formula, Dragulescu and Yakovenko19 suggested that any conserved quantity in a big statistical system has an exponential probability distribution in equilibrium. With respect to individual variability and total stability, the conditions that enable exponential distribution could be present in the distributions of the 16 negative items. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanism.

Different patterns with a boundary at ‘Some’

The reason why the distributions of the 16 negative items display different patterns with a boundary at ‘Some’ is unknown, but the conditions that enable such a distribution can be speculated on. In fact, psychological phenomena are evaluated using an ordinal scale.20 Unlike an interval scale, an ordinal scale is not necessarily equally spaced. If the range for ‘Rarely’ differs from that of ‘Some’, ‘Much’ and ‘Most’, the distributions of the 16 negative items would display different patterns with a boundary at ‘Some’.

In general, each item of CES-D is rated in two stages. First, the population is divided according the presence or absence of the symptom. If the symptom of each item is absent, it is regarded as ‘Rarely’. Next, if the symptom of each item is present, the duration of the symptom is quantified and divided into ‘Some’, ‘Much’ and ‘Most’. This two-step process increases the possibility that ‘Rarely’ will cover the participants without the symptom, while each of ‘Some’, ‘Much’ and ‘Most’ will cover about one-third of the range with the symptom. In other words, ‘Rarely’ is scored using a purely ordinal scale, whereas ‘Some’, ‘Much’ and ‘Most’ are scored using an ordinal scale that is close to an interval scale. Further consideration regarding this speculation is needed.

Distributions of the positive affect items

Although the distributions of the four positive affects showed a plateau-shaped distribution in this study, the evidence for the distributions of positive affect symptoms has been mixed. To the best of our knowledge, no common response patterns to positive affect symptom items have been reported so far. A number of cross-cultural comparison studies have reported that the response patterns for the positive affects items vary according to ethnicity or nation (eg, skewed, plateau-shaped, U-shaped and reverse U-shaped), whereas the response patterns for the 16 negative items were generally comparable.21 22 Recently, because of their relative independence, positive affect and negative affect have been commonly recognised as two different phenomena that should be studied individually.23 24 Our results lend credibility to the view that positive affect and negative affect are two different phenomena. Although the CES-D score is the composite score of the 20-item scores, it could be appropriate to recognise the 16 negative item scores and the positive scores as different scores.

Strengths and limitations

There are some methodological advantages in the present investigation. First, the sample was representative of the general Japanese population. Survey participants were selected among individuals living in 300 communities, which were selected from 881 851 precincts identified in the 1995 census using a stratified sampling design. The use of a representative sample of the Japanese general population reduced the selection bias of the data. Second, the relatively large sample size (N=32 022) increased the ability to elucidate the patterns of the distributions of depressive symptom items.

This study has some limitations. First, a standard psychiatric diagnosis with structured interview was not performed for the participants in this study. Therefore, the study did not encompass a psychiatric diagnosis of depressive symptoms. Second, although the 16 negative symptom items exhibited a linear pattern with a log-normal scale, analysis based on other mathematical models was not performed. In general, the most important part of model evaluation is testing whether the model better fits empirical data than other models. However, to the best of our knowledge, no other mathematical models for the distributions of depressive symptoms have been reported so far. Therefore, it is difficult to test whether the estimated data of the present model fit empirical data better than those of other models. Thus, using graphical analysis, we propose a simple model that consists of only two parameters as a baseline for improvement. In general, there is a trade-off between the goodness of fit and complexity of the model.

Despite these limitations, the present study provides important information regarding the theory of a self-report depression scale. The scores of a self-report depression scale can be interpreted in a norm-referenced manner. A norm-referenced score interpretation compares individual’s scores on the test with the statistical representation of a population. One representation of statistical norms is the normal distribution, which is adopted as the distribution model of intelligence. The statistical norm is useful to evaluate the scores of the individuals in a population and to verify the result of the survey. The present model could provide a statistical norm for a self-report depression scale.

The degree to which these results can be generalised to other scales for depressive symptoms is unclear, but warrants examination. While the item scale of CES-D assesses the frequency of a variety of depressive symptoms within the previous week, others (eg, CIS-R) are composites of frequency, salience and severity. Given that depressive symptoms, such as depressed mood, anxiety and insomnia, affect people worldwide, an overarching mathematical model explaining the distributions of depressive symptom scores in a general population could be useful.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Active Survey of Health and Welfare project for providing the data for this study, and Dr Shinji Sakamoto for the helpful advice.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors participated in the study, and read and approved the final manuscript. ST conceived and designed the experiments, and performed the experiments. ST, YK and TF were involved in interpretation of data for the work and wrote the paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Our present study was approved in 2014 by the ethics committee of Panasonic Health Center, approval number 2014–1. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E et al. . Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007;370:851–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Foster C, Webster PS. et al. The relationship between age and depressive symptoms in two national surveys. Psychol Aging 1992;7:119–26. 10.1037/0882-7974.7.1.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Milaneschi Y et al. . The trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult life span. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:803–11. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bebbington PE, Dunn G, Jenkins R et al. . The influence of age and sex on the prevalence of depressive conditions: report from the National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. Psychol Med 1998;28:9–19. 10.1017/S0033291797006077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomitaka S, Kawasaki Y, Furukawa T. Right tail of the distribution of depressive symptoms is stable and follows an exponential curve during middle adulthood. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0114624 10.1371/journal.pone.0114624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melzer D, Tom BD, Brugha TS et al. . Common mental disorder symptom counts in populations: are there distinct case groups above epidemiological cut-offs? Psychol Med 2002;32:1195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R et al. . Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behav Res Ther 1997;35:373–80. 10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00107-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams CD, Taylor TR, Makambi K et al. . CES-D four-factor structure is confirmed, but not invariant, in a large cohort of African American women. Psychiatry Res 2007;150:173–80. 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shafer AB. Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. J Clin Psychol 2006;62:123–46. 10.1002/jclp.20213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Statistics and Information Department. Active survey of health and welfare health. (in Japanese). Tokyo: Labor and Welfare Statistics Association, 2002:1–120. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaji T, Mishima K, Kitamura S et al. . Relationship between late-life depression and life stressors: large-scale cross-sectional study of a representative sample of the Japanese general population. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010;64:426–34. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole SR, Kawachi I, Maller SJ et al. . Test of item-response bias in the CES-D scale: experience from the New Haven EPESE study. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:285–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00151-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwata N, Umesue M, Egashira K et al. . Can positive affect items be used to assess depressive disorders in the Japanese population? Psychol Med 1998;28:153–8. 10.1017/S0033291797005898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang Y, Kwag KH, Chiriboga DA et al. . Not saying I am happy does not mean I am not: cultural influences on responses to positive affect items in the CES-D. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2010;65:684–90. 10.1093/geronb/gbq052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley KL, Reed PS, Mutran EJ et al. . Measurement adequacy of the CES-D among a sample of older African–Americans. Psychiatry Res 2002;109:61–9. 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR et al. . The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:2163–77. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olino TM, Yu L, Klein DN et al. . Measuring depression using item response theory: an examination of three measures of depressive symptomatology. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2012;21:76–85. 10.1002/mpr.1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dragulescu A, Yakovenko VM. Statistical mechanics of money. Eur Phys J B Condensed Matter Complex Syst 2000;17:723–9. 10.1007/s100510070114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens SS. On the theory of scales of measurement. Science 1946;103:677–80. 10.1126/science.103.2684.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho MJ, Kim KH. Use of the center for epidemiologic studies depression (CES-D) scale in Korea. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998;186:304–10. 10.1097/00005053-199805000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwata N, Buka S. Race/ethnicity and depressive symptoms: a cross-cultural/ethnic comparison among university students in East Asia, North and South America. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:2243–52. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diener E, Larsen RJ. The experience of emotional well-being. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM, eds. Handbook of emotions. New York: Guilford, 1993:405–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucas RE, Diener E, Suh E. Discriminant validity of well-being measures. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;71:616–28. 10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]