Abstract

Objective

A recent analysis of the Australian National Health Survey (2011–2012) reported that the patterning of overweight and obesity among men, unlike for women, was not associated with neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage. The purpose of this study was to examine whether this gender difference in potential neighbourhood ‘effects’ on adult weight status can be observed in analyses of a different source of data.

Design, setting and participants

A cross-sectional sample of 14 693 people aged 18 years or older was selected from the 2012 wave of the ‘Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia’ (HILDA). Three person-level outcomes were considered: (1) body mass index (BMI); (2) a binary indicator of ‘normal weight’ versus ‘overweight or obese’; and (3) ‘normal weight or overweight’ versus ‘obese’. Area-level socioeconomic circumstances were measured using quintiles of the Socio Economic Index For Areas (SEIFA). Multilevel linear and logistic regression models were used to examine associations while accounting for clustering within households and neighbourhoods, adjusting for person-level socioeconomic confounders.

Results

Neighbourhood-level factors accounted for 4.9% of the overall variation in BMI, whereas 20.1% was attributable to household-level factors. Compared with their peers living in deprived neighbourhoods, mean BMI was 0.7 kg/m2 lower among men and 2.2 kg/m2 lower among women living in affluent areas, with a clear trend across categories. Similarly, the percentage of overweight and obese, and obesity specifically, was lower in affluent areas for both men and women. These results were robust to adjustment for confounders.

Conclusions

Unlike findings from the national health survey, but in line with evidence from other high-income countries, this study finds an inverse patterning of BMI by neighbourhood disadvantage for men, and especially among women. The potential mediators which underpin this gender difference in BMI within disadvantaged neighbourhoods warrant further investigation.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, SOCIAL MEDICINE, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Nationally representative household survey.

Multilevel modelling to disentangle person, household and neighbourhood effects.

Limited by self-reported data.

Introduction

Overweight and obesity in Australia and most middle and upper-income countries is potentially the major public health challenge of the 21st century.1 2 The prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australia has now risen to 62.8% according to the most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) national health survey of 2011–2012.3 Despite the evidence of this epidemic, the Australian government cut funding for chronic disease prevention and the major agency set up to deal with it.4

The reported rise in overweight and obesity is likely to be driven by an obesogenic environment, combining a relatively sedentary and inactive lifestyle with ongoing passive overconsumption of energy,5 made easy due to the increasing availability, affordability and effective marketing of processed energy dense foods.6

Much research has been published on the complex web of social determinants of weight status, including the characteristics of individuals and the places in which they live.7–9 Although the social patterning of overweight and obesity does vary geographically, within high-income nations men and women of all age groups are affected, but especially those who live in socioeconomically disadvantaged circumstances.10 11 There remains some debate as to how much some of these patterns, such as the higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods, is due to causal pathways or health-selective forces.12

A recent press release entitled “Health is where your home is”13 from the ABS reported that the prevalence of objectively-measured overweight and obesity was higher among women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. The same was not observed for men. This finding from the Australian National Health Survey (2011–2012) is somewhat controversial as it does not reflect the bulk of previous evidence.7–9

The purpose of this study was to attempt to replicate the ABS's finding using the same outcome and exposure measures collected around the same time period as the national health survey 2011–2012, but from an entirely separate source of nationally representative data. We asked the following research question: “To what extent are body mass index (BMI) and the odds of being overweight or obese lower in more affluent neighbourhoods for women, but not men?”

Data and method

The ‘Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia’ (HILDA) survey is a nationally representative sample collecting data on approximately 15 000 individuals each year living in about 7000 households. Detailed information on sampling and other aspects of HILDA are published elsewhere.14 A cross-sectional sample of 17 476 people aged 18 years or older was selected from the 2012 wave. Self-reported height and weight were used to calculate BMI for each participant. Approximately 2785 were omitted as either insufficient data were available to enable this calculation (n=2730) or their BMI was judged to be unrealistic (n=55). These restrictions left a sample of 14 691 participants for analysis.

Three person-level outcomes were considered:

A person's BMI in its continuous form;

A binary variable denoting whether a person was (1) ‘normal weight’ or (2) ‘overweight’ or ‘obese’. To facilitate this, the WHO criteria were used to define cut-points for ‘normal weight’ (BMI 18.5–24.9), ‘overweight’ (BMI 25–29.9), ‘obese’ (BMI ≥30) and ‘underweight’ (BMI <18.5). This binary variable therefore omitted persons considered to be ‘underweight’ (n=399).

A binary variable denoting whether a person was (1) ‘normal weight’ or ‘overweight’ or (2) ‘obese’, derived from the same WHO criteria. This binary variable also omitted persons considered to be ‘underweight’.

In line with the ABS analyses, the area-level measure of socioeconomic circumstances was taken from the Socio Economic Index For Areas (SEIFA). We opted to use the index of relative disadvantage, which is a composite indicator summarising multiple Census variables which describe socioeconomic circumstances.15 As the SEIFA index is provided as a rank, we transformed it into quintiles wherein higher strata denote less favourable socioeconomic circumstances.

A range of variables were identified to help address probable sources of confounding based on a synthesis of previous literature.9 16 17 These included gender, age, demographic and person-level socioeconomic factors. Demographic factors consisted of whether a participant was living on their own or as part of a couple (married or cohabiting), the number of children in the household (0, 1, 2, 3 or more) and if somebody in the household had been pregnant in the past 12 months (not the participant specifically). Socioeconomic confounders included the highest level of education achieved (less than high school, high school to advanced diploma, university or higher), average household gross income (expressed in quintiles) and the percentage of time in the past year spent unemployed.

Since HILDA is a household survey, the rationale for using multilevel models provided in the introduction of this paper was also relevant to this analysis. Accordingly, we fitted multilevel linear regression models to assess the degree of association between BMI and neighbourhood socioeconomic circumstances. Multilevel logistic regression was used to conduct the same analyses for the two binary outcome variables. In all models, participants were fitted at level 1. These participants were nested within households, fitted at level 2. Finally, households were clustered within neighbourhoods (level 3), defined as Census Collection Districts (‘CCDs’), which are small areas containing approximately 225 residential dwellings on average.

The first model assessed the degree of association between each outcome and neighbourhood socioeconomic quintiles, adjusted for participants’ gender and age (with the latter fitted as both linear and square terms to account for curvilinear associations between weight status and age). To explore the gender differential in each outcome by neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage, an interaction term was fitted between each of these variables in model 2. Finally, we examined the robustness of the findings to controls for the person-level socioeconomic confounders. The ‘Variance Partition Coefficient’ (VPC) and ‘Median OR’ (MOR) were used to describe the relative importance of neighbourhoods and households for responses to each of the linear and binary outcomes, respectively.18 Fully adjusted interaction terms are illustrated using predicted means or probabilities and 95% CIs. All analyses were conducted in MLwIN V.2.30.19 Ethical approval for the HILDA study was obtained from the Faculty of Business and Economics Human Ethics Advisory Committee at the University of Melbourne. Approval for the use of HILDA data was provided by the Government Department of Social Services.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the study sample are provided according to quintiles of the neighbourhood socioeconomic circumstances variable (table 1). In addition, owing to the focus on gender differences, these descriptions are provided for men and women separately. Compared with their peers living in deprived neighbourhoods, mean BMI was 1 kg/m2 lower among men and 2 kg/m2 lower among women living in affluent areas, with a clear trend across categories. Similarly, the percentage of overweight or obese, and obesity specifically, was lower in affluent areas for both men and women. The average age for each gender tended to be similar across neighbourhood socioeconomic circumstances. In disadvantaged areas, there was a lower prevalence of couples and university educated participants, lower non-employment and lower household disposable incomes.

Table 1.

Sample descriptive statistics

| SEIFA relative index of disadvantage quintiles | |||||

| Male | 1 (Affluent) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (Deprived) |

| N | 1520 | 1562 | 1572 | 1573 | 1535 |

| (95% CI) | |||||

| Body mass index (mean) | 26.3 (26.0 to 26.6) | 26.6 (26.3 to 26.9) | 27.2 (26.9 to 27.5) | 27.5 (27.2 to 27.8) | 27.3 (27.0 to 27.6) |

| Overweight or obese (%) | 58.8 (56.2 to 61.3) | 62.9 (60.3 to 65.4) | 65.4 (62.8 to 67.9) | 67.0 (64.4 to 69.4) | 62.7 (60.2 to 65.2) |

| Obese (%) | 16.6 (14.7 to 18.6) | 19.1 (17.1 to 21.2) | 23.9 (21.7 to 26.2) | 26.4 (24.2 to 28.8) | 26.2 (24.0 to 28.6) |

| Age (years, mean) | 45.6 (44.6 to 46.5) | 45.1 (44.1 to 46.1) | 43.5 (42.5 to 44.5) | 45.4 (44.4 to 46.4) | 45.1 (44.1 to 46.1) |

| In a couple (%) | 69.4 (67.0 to 71.8) | 69.7 (67.2 to 72.1) | 69.8 (67.3 to 72.2) | 67.0 (64.4 to 69.4) | 58.4 (55.8 to 61.0) |

| University education (%) | 41.9 (39.3 to 44.5) | 26.0 (23.7 to 28.3) | 19.4 (17.4 to 21.6) | 16.4 (14.6 to 18.5) | 11.9 (10.3 to 13.6) |

| Not unemployed (%) | 93.1 (91.7 to 94.4) | 91.9 (90.4 to 93.3) | 90.4 (88.7 to 91.9) | 89.6 (87.9 to 91.1) | 87.2 (85.4 to 88.8) |

| High disposable income (%)* | 39.6 (37.0 to 42.2) | 20.5 (18.4 to 22.7) | 20.7 (18.6 to 22.9) | 13.8 (12.1 to 15.7) | 9.4 (8.0 to 11.1) |

| SEIFA relative index of disadvantage quintiles | |||||

| Female | 1 (Affluent) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (Deprived) |

| N | 1419 | 1378 | 1365 | 1368 | 1401 |

| (95% CI) | |||||

| Body mass index (mean) | 25.1 (24.8 to 25.3) | 26.1 (25.8 to 26.4) | 26.6 (26.3 to 26.9) | 27.1 (26.8 to 27.4) | 27.5 (27.2 to 27.8) |

| Overweight or obese (%) | 41.0 (38.5 to 43.4) | 48.4 (46.0 to 50.9) | 52.7 (50.2 to 55.1) | 54.9 (52.4 to 57.3) | 58.7 (56.2 to 61.2) |

| Obese (%) | 15.2 (13.5 to 17.1) | 21.5 (19.5 to 23.6) | 25.0 (23.0 to 27.2) | 26.6 (24.5 to 28.8) | 29.6 (27.4 to 32.0) |

| Age (years, mean) | 45.6 (44.7 to 46.5) | 45.0 (44.1 to 45.9) | 44.0 (43.1 to 44.9) | 45.2 (44.2 to 46.1) | 46.2 (45.3 to 47.2) |

| In a couple (%) | 65.4 (63.0 to 67.8) | 64.7 (62.3 to 67.0) | 62.3 (59.9 to 64.7) | 60.1 (57.6 to 62.5) | 55.8 (53.3 to 58.3) |

| University education (%) | 41.2 (38.8 to 43.7) | 30.3 (28.0 to 32.6) | 24.4 (22.3 to 26.6) | 19.2 (17.3 to 21.2) | 15.6 (13.9 to 17.5) |

| Not unemployed (%) | 93.0 (91.6 to 94.2) | 91.6 (90.1 to 92.9) | 92.0 (90.5 to 93.2) | 89.8 (88.2 to 91.2) | 88.6 (86.9 to 90.1) |

| High disposable income (%)* | 37.6 (35.3 to 40.1) | 19.6 (17.7 to 21.7) | 18.0 (16.2 to 20.0) | 12.5 (11.0 to 14.2) | 8.7 (7.4 to 10.2) |

Body mass index measured in kg/m2.

*High disposable income=quintile 5 (≥A$133K).

SEIFA, Socio Economic Index For Areas.

An analysis of missing outcome data was conducted using logistic regression. The odds of having a missing weight status were significantly higher among participants not in couples (OR 1.729, 95% CI 1.593 to 1.876) and those who had experienced long periods of unemployment in the past 12 months (OR75–100% 2.200, 95% CI 1.781 to 2.719), but lower among older participants (OR 0.997, 95% CI 0.985 to 0.989), those with a university education (OR 0.488, 95% CI 0.434 to 0.549) and among participants with high household disposable incomes (ORquintile5 0.488, 95% CI 0.434 to 0.549) No significant difference was found by gender.

Variance components models were fitted to assess the contributions of each level across all three outcome variables. For BMI, neighbourhoods contributed 4.9% and 20.1% by households. Approximately 3.8% of variation in the prevalence of overweight and obesity was determined by neighbourhood factors compared with 5.7% at the household level. Specifically, for obesity, 6.5% of the variation was reported at the neighbourhood level, whereas 20.8% manifested between households.

The findings from the adjusted models are reported in tables 2–4. The 14 691 participants were nested within 8287 households (mean=1.8, min=1, max=9) and 4670 CCDs (mean=3.1, min=1, max=45). Approximately 41.1% of households contained just one participant (n=3409), with a further 46.1% (n=3819) of households containing two participants. BMI was lower among younger participants, women and those in more affluent neighbourhoods (table 2, model 1). A significant interaction was observed, with BMI significantly lower among women than men in affluent neighbourhoods, but heavier than men in the more disadvantaged areas (table 2, model 2). Adjusting for confounders did not fully attenuate the interaction between gender and neighbourhood socioeconomic circumstances (table 2, model 3). Similar results were observed for overweight and obesity (table 3) and specifically for obesity (table 4).

Table 2.

Association between body mass index and neighbourhood deprivation—multilevel linear regression

| Coefficient (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Fixed part | |||

| Age (years) | 0.348 (0.324 to 0.371) | 0.348 (0.324 to 0.371) | 0.369 (0.343 to 0.396) |

| Age2 | −0.003 (−0.003 to −0.003) | −0.003 (−0.003 to −0.003) | −0.003 (−0.004 to −0.003) |

| Gender (ref: male) | |||

| Female | −0.538 (−0.699 to −0.376) | ||

| Neighbourhood disadvantage (ref: quintile 1) | |||

| Quintile 2 | 0.759 (0.411 to 1.107) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 1.300 (0.954 to 1.647) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 1.677 (1.335 to 2.020) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 1.857 (1.513 to 2.200) | ||

| Gender×neighbourhood disadvantage | |||

| (ref: male×quintile 1) | |||

| Male×quintile 2 | 0.406 (−0.032 to 0.845) | 0.196 (−0.243 to 0.634) | |

| Male×quintile 3 | 0.927 (0.486 to 1.369) | 0.637 (0.193 to 1.081) | |

| Male×quintile 4 | 1.263 (0.827 to 1.700) | 0.916 (0.474 to 1.359) | |

| Male×quintile 5 | 1.087 (0.651 to 1.522) | 0.698 (0.253 to 1.144) | |

| Female×quintile 1 | −1.261 (−1.621 to −0.902) | −1.287 (−1.647 to −0.927) | |

| Female×quintile 2 | −0.184 (−0.614 to 0.247) | −0.378 (−0.809 to 0.053) | |

| Female×quintile 3 | 0.376 (−0.051 to 0.803) | 0.126 (−0.303 to 0.555) | |

| Female×quintile 4 | 0.788 (0.363 to 1.212) | 0.457 (0.026 to 0.888) | |

| Female×quintile 5 | 1.295 (0.866 to 1.723) | 0.920 (0.480 to 1.359) | |

| Couple status (ref: yes) | |||

| No | −0.208 (−0.430 to 0.014) | ||

| Missing | 0.792 (−1.731 to 3.315) | ||

| Highest educational qualification (ref: ≤year 11) | |||

| Year 12 to adv. Diploma | −0.182 (−0.397 to 0.033) | ||

| University | −1.065 (−1.333 to −0.797) | ||

| Missing | −1.198 (−4.898 to 2.501) | ||

| Percentage of previous year spent unemployed (ref: 0%) | |||

| 1–24 | 0.149 (−0.320 to 0.618) | ||

| 25–49 | 0.428 (−0.166 to 1.022) | ||

| 50–74 | 0.554 (−0.202 to 1.309) | ||

| 75–100 | 0.030 (−0.573 to 0.633) | ||

| Disposable household income (ref: quintile 1) | |||

| Quintile 2 | −0.274 (−0.592 to 0.043) | ||

| Quintile 3 | −0.188 (−0.529 to 0.153) | ||

| Quintile 4 | −0.231 (−0.586 to 0.123) | ||

| Quintile 5 | −0.453 (−0.819 to −0.087) | ||

| Random part | |||

| Level 3 (census collection district) | 1.202 (0.252) | 1.195 (0.251) | 1.032 (0.241) |

| Variance partition coefficient* | 3.9% | ||

| Level 2 (Household) | 7.225 (0.431) | 7.286 (0.430) | 7.081 (0.425) |

| Variance partition coefficient* | 23.5% | ||

| Level 1 (Person) | 22.337 (0.379) | 22.236 (0.377) | 22.317 (0.378) |

| Variance partition coefficient* | 72.6% | ||

Body mass index measured in kg/m2.

*Variance partition coefficient presented for model 1 only.

Table 3.

Odds of being overweight or obese versus ‘normal’ weight and neighbourhood deprivation—multilevel logistic regression

| OR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Fixed part | |||

| Age (years) | 1.140 (1.128 to 1.151) | 1.140 (1.129 to 1.152) | 1.139 (1.126 to 1.152) |

| Age2 | 0.999 (0.999 to 0.999) | 0.999 (0.999 to 0.999) | 0.999 (0.999 to 0.999) |

| Gender (ref: male) | |||

| Female | 0.541 (0.503 to 0.581) | ||

| Neighbourhood disadvantage (ref: quintile 1) | |||

| Quintile 2 | 1.363 (1.198 to 1.551) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 1.620 (1.424 to 1.844) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 1.752 (1.541 to 1.992) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 1.826 (1.605 to 2.078) | ||

| Gender×neighbourhood disadvantage | |||

| (ref: male×quintile 1) | |||

| Male×quintile 2 | 1.264 (1.058 to 1.509) | 1.192 (0.998 to 1.423) | |

| Male×quintile 3 | 1.435 (1.198 to 1.718) | 1.326 (1.106 to 1.589) | |

| Male×quintile 4 | 1.524 (1.274 to 1.824) | 1.401 (1.168 to 1.680) | |

| Male×quintile 5 | 1.296 (1.087 to 1.546) | 1.202 (1.003 to 1.440) | |

| Female×quintile 1 | 0.417 (0.356 to 0.489) | 0.420 (0.358 to 0.492) | |

| Female×quintile 2 | 0.613 (0.517 to 0.727) | 0.591 (0.498 to 0.701) | |

| Female×quintile 3 | 0.758 (0.640 to 0.898) | 0.721 (0.608 to 0.855) | |

| Female×quintile 4 | 0.832 (0.703 to 0.984) | 0.779 (0.656 to 0.925) | |

| Female×quintile 5 | 1.034 (0.871 to 1.227) | 0.967 (0.811 to 1.152) | |

| Couple status (ref: yes) | |||

| No | 0.849 (0.777 to 0.929) | ||

| Missing | 1.612 (0.508 to 5.117) | ||

| Highest educational qualification (ref: ≤year 11) | |||

| Year 12 to adv. Diploma | 0.968 (0.883 to 1.062) | ||

| University | 0.697 (0.624 to 0.779) | ||

| Missing | 0.170 (0.029 to 1.007) | ||

| Percentage of previous year spent unemployed (ref: 0%) | |||

| 1–24 | 1.135 (0.929 to 1.388) | ||

| 25–49 | 1.057 (0.820 to 1.362) | ||

| 50–74 | 0.985 (0.713 to 1.361) | ||

| 75–100 | 0.874 (0.676 to 1.131) | ||

| Disposable household income (ref: quintile 1) | |||

| Quintile 2 | 0.991 (0.873 to 1.123) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 1.018 (0.890 to 1.164) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 1.048 (0.912 to 1.204) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 1.005 (0.872 to 1.159) | ||

| Random part | |||

| Level 3 (census collection district) | |||

| Variance (SE) | 0.118 (0.034) | 0.118 (0.034) | 0.098 (0.033) |

| Variance partition coefficient* | 1.0% | ||

| Median OR (95% CI) | 1.26 (1.19 to 1.33) | 1.26 (1.19 to 1.33) | 1.23 (1.17 to 1.29) |

| Level 2 (Household) | |||

| Variance (SE) | 0.405 (0.054) | 0.417 (0.055) | 0.406 (0.054) |

| Variance partition coefficient* | 3.6% | ||

| Median OR (95% CI) | 1.54 (1.43 to 1.65) | 1.55 (1.44 to 1.66) | 1.54 (1.43 to 1.65) |

Body mass index measured in kg/m2.

*Variance partition coefficient presented for model 1 only.

Table 4.

Odds of being obese versus ‘normal’ or overweight and neighbourhood deprivation—multilevel logistic regression

| OR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Fixed part | |||

| Age (years) | 1.144 (1.128 to 1.161) | 1.144 (1.128 to 1.161) | 1.159 (1.141 to 1.177) |

| Age2 | 0.999 (0.999 to 0.999) | 0.999 (0.999 to 0.999) | 0.999 (0.998 to 0.999) |

| Gender (ref: male) | |||

| Female | 1.077 (0.986 to 1.177) | ||

| Neighbourhood disadvantage (ref: quintile 1) | |||

| Quintile 2 | 1.473 (1.222 to 1.774) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 2.011 (1.678 to 2.410) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 2.289 (1.916 to 2.734) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 2.574 (2.155 to 3.073) | ||

| Gender×neighbourhood disadvantage | |||

| (ref: male×quintile 1) | |||

| Male×quintile 2 | 1.255 (0.979 to 1.609) | 1.159 (1.141 to 1.177) | |

| Male×quintile 3 | 1.817 (1.428 to 2.311) | 0.999 (0.998 to 0.999) | |

| Male×quintile 4 | 2.140 (1.692 to 2.707) | 1.000 (1.000 to 1.000) | |

| Male×quintile 5 | 2.169 (1.715 to 2.743) | 1.107 (0.867 to 1.414) | |

| Female×quintile 1 | 0.883 (0.701 to 1.111) | 1.514 (1.193 to 1.922) | |

| Female×quintile 2 | 1.500 (1.182 to 1.904) | 1.725 (1.364 to 2.181) | |

| Female×quintile 3 | 1.950 (1.546 to 2.458) | 1.698 (1.340 to 2.152) | |

| Female×quintile 4 | 2.157 (1.715 to 2.712) | 0.862 (0.686 to 1.084) | |

| Female×quintile 5 | 2.654 (2.112 to 3.336) | 1.324 (1.046 to 1.677) | |

| Couple status (ref: yes) | |||

| No | 1.741 (1.384 to 2.191) | ||

| Missing | 2.081 (1.651 to 2.623) | ||

| Highest educational qualification (ref: ≤year 11) | |||

| Year 12 to adv. Diploma | 0.927 (0.783 to 1.096) | ||

| University | 0.909 (0.762 to 1.084) | ||

| Missing | 0.835 (0.694 to 1.005) | ||

| Percentage of previous year spent unemployed (ref: 0%) | |||

| 1–24 | 1.226 (0.945 to 1.591) | ||

| 25–49 | 1.464 (1.067 to 2.010) | ||

| 50–74 | 1.154 (0.757 to 1.759) | ||

| 75–100 | 1.139 (0.824 to 1.574) | ||

| Disposable household income (ref: quintile 1) | |||

| Quintile 2 | 0.877 (0.750 to 1.025) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 0.927 (0.783 to 1.096) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 0.909 (0.762 to 1.084) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 0.835 (0.694 to 1.005) | ||

| Random part | |||

| Level 3 (census collection district) | |||

| Variance (SE) | 0.221 (0.058) | 0.219 (0.058) | 0.175 (0.053) |

| Variance partition coefficient* | 1.8% | ||

| Median OR (95% CI) | 1.37 (1.26 to 1.48) | 1.37 (1.26 to 1.48) | 1.33 (1.23 to 1.43) |

| Level 2 (Household) | |||

| Variance (SE) | 0.965 (0.090) | 0.973 (0.090) | 0.873 (0.086) |

| Variance partition coefficient* | 8.0% | ||

| Median OR (95% CI) | 1.94 (1.76 to 2.12) | 1.94 (1.76 to 2.12) | 1.88 (1.71 to 2.05) |

Body mass index measured in kg/m2.

*Variance partition coefficient presented for model 1 only.

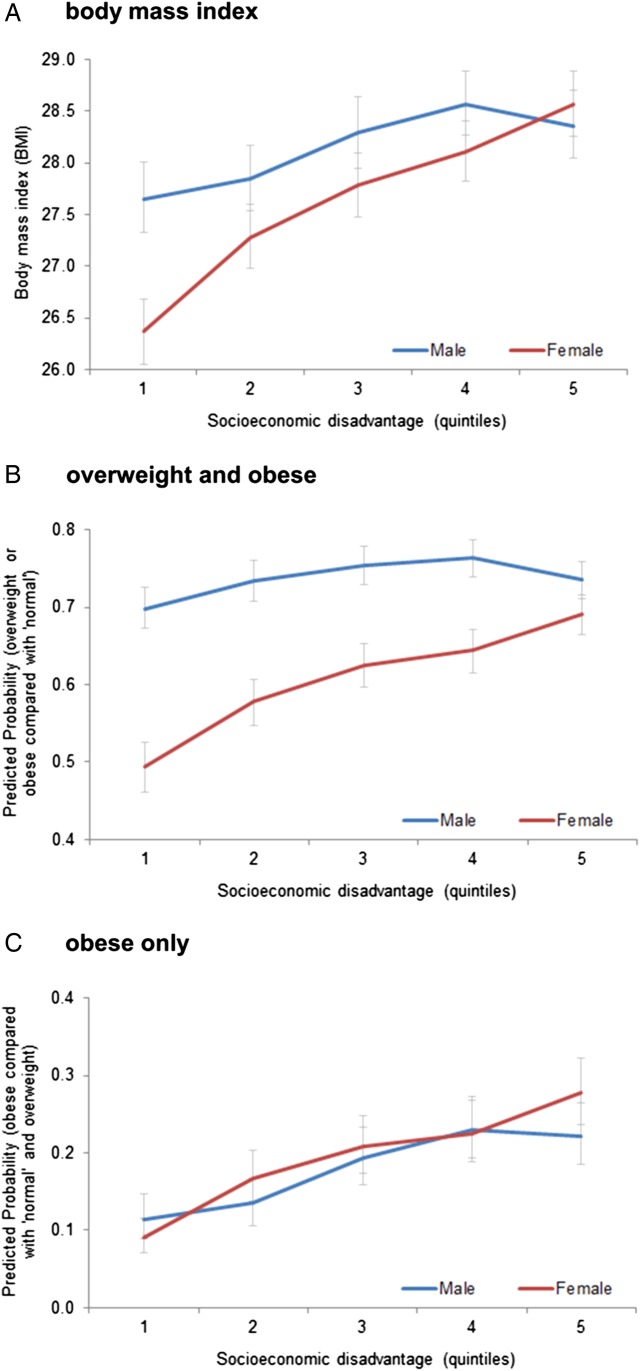

Figure 1 illustrates the gender by neighbourhood interaction using predicted means/probabilities. From figure 1A, it is clear that mean BMI is demonstrably lower in more affluent areas not only for women, but also for men. This negative slope is somewhat shallower for men than women when considering the odds of being ‘overweight’ or ‘obese’ versus ‘normal weight’ (figure 1B). In contrast, the odds of being ‘obese’ versus ‘normal weight’ or ‘overweight’ (figure 1C) were lower in neighbourhoods with more favourable socioeconomic circumstances, though with far less of a gender difference.

Figure 1.

Association between weight status and neighbourhood deprivation, by gender (predicted means and probabilities from three separate fully adjusted multilevel models).

Discussion

Recent findings from the Australian national health survey 2011–2012 suggest that men living in more affluent neighbourhoods are no less likely to be overweight or obese than their counterparts living in disadvantaged areas.13 In this study, we found contradictory evidence to the ABS's result. Instead, using a separate source of nationally representative data containing the same measures that were collected within the same time period as the national health survey, we found that men living in more affluent areas had a lower BMI and a lower odds of being overweight or obese than men living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Our results, unlike those from the Australian national health survey, tend to fall in line with international evidence.7–11

It is difficult to ascertain why the ABS has provided this result without further investigation using the actual data. The same SEIFA relative index of disadvantage was used in both studies, though one point of difference is that our data contained weight status outcomes based on self-reported height and weight, whereas 83% of participants in the Australian Health Survey had objectively measured outcomes. It is not clear, however, whether this would influence men more so than women to explain the difference in results between each study.

It is notable, though, that in both analyses the socioeconomic patterning of overweight and obesity among women was reasonably substantial. Hypotheses with varying plausibility to explain this gendered pattern are not straightforward, but may be related to the level of connectedness to the local environment and to the neighbours who people live nearby. If women are more likely than men to take responsibility for household-related tasks, for example, they may then potentially spend more time in their neighbourhood as a result.20 21 If more affluent neighbourhoods tend to promote lower BMI, as many, though not all, commentators suggest,12 then the duration of exposure could play a role in explaining gender differences in the socioeconomic patterning of overweight and obesity. Furthermore, women in some contexts may also tend to be involved more often in activities that take place in the local area, such as schools and community groups.22 The social networks developed through these activities23–25 may act as conduits for the spread of health-relevant behaviours and have an effect on weight status.26–28 Causal inferences cannot be drawn as the data analysed are cross-sectional, though future longitudinal research with HILDA is possible due to the repeated follow-up of the same participants over time.

Aside from the main result, it is of additional interest to note how important the household level was for explaining variation in weight status. About 5.6% of the variation in BMI could be attributed to neighbourhood-level factors, whereas around 23% were attributable to the households. This partitioning of variance between people and households is scantily reported in the literature since most studies involve the analysis of surveys in which only one person per household responds. Therefore, this study extends the literature in this regard. It suggests that who we live with is likely to be quite important for determining how healthy we are. As such, the correlates of household-level characteristics and weight status would be important areas for future research.

Conclusions

In this study, both men and women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods had higher weight status than their counterparts in more affluent areas. These findings are in line with previous work carried out in other high-income countries, but not the most recent from the Australian national health survey. Reasons for the gender difference in BMI between men and women living in disadvantaged areas require further hypothesis testing, especially with longitudinal data. Finally, more work should be carried out on household-level determinants of overweight and obesity.

Footnotes

Contributors: XF conceptualised the research question, conducted the analyses, interpreted the results and wrote the first and final drafts of the manuscript. AW had input into the conceptualisation of the research question and study design, the interpretation of the results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding: This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the author and should not be attributed to either the DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) data are used under strict licensing. Data can be potentially obtained subject to a peer-reviewed application. Further details are available at: https://www.melbourneinstitute.com/hilda/

References

- 1.Colagiuri S, Lee CM, Colagiuri R et al. The cost of overweight and obesity in Australia. Med J Aust 2010;192:260–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T et al. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011;378:815–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.003—Australian Health Survey: Updated Results, 2011–2012: Overweight and obesity. Secondary 4364.0.55.003—Australian Health Survey: Updated Results, 2011–2012: Overweight and obesity 2013. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/33C64022ABB5ECD5CA257B8200179437?opendocument

- 4.Wilson A. Budget cuts risk halting Australia's progress in preventing chronic disease. Med J Aust 2014;200:558 10.5694/mja14.00726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D et al. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. Lancet 2011;378:826–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60812-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckersley R. Is modern Western culture a health hazard? Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:252–8. 10.1093/ije/dyi235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC et al. The built environment and obesity: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health Place 2010;16:175–90. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States—gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:6–28. 10.1093/epirev/mxm007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M et al. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev 2009;31:7–20. 10.1093/epirev/mxp005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011;378:804–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:29–48. 10.1093/epirev/mxm001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casazza K, Fontaine KR, Astrup A et al. Myths, presumptions, and facts about obesity. N Engl J Med 2013;368:446–54. 10.1056/NEJMsa1208051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.003—Australian Health Survey: Updated Results, 2011–2012: MEDIA RELEASE: Health depends on where your home is. Secondary 4364.0.55.003—Australian Health Survey: Updated Results, 2011–2012: MEDIA RELEASE: Health depends on where your home is 2013. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookup/4364.0.55.003Media%20Release12011–2012

- 14.Watson N, Wooden M. The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey: Wave 1 Survey Methodology. HILDA Project Technical Paper Series no. 1/02, May Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pink B. Technical paper: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:125–45. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhoods and health. USA: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:290–7. 10.1136/jech.2004.029454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasbash J, Browne W, Goldstein H et al. A user's guide to MLwiN, v2. 26. Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol. 2012. Vol 286 2nd edn London: Institute of Education, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwan MP. Gender differences in space-time constraints. Area 2000;32:145–56. 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2000.tb00125.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig L, Powell A, Brown JE. Gender patterns in domestic labour among young adults in different living arrangements in Australia. J Sociol 2015. doi:1440783315593181. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Healy K, Haynes M, Hampshire A. Gender, social capital and location: understanding the interactions. Int J Soc Welf 2007;16:110–18. 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2006.00471.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarvis H. The tangled webs we weave: household strategies to co-ordinate work and home. Work Employment Soc 1999;13:225–47. 10.1177/09500179922117926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell H. Friends in low places: gender, unemployment and sociability. Work Employment Soc 1999;13:205–24. 10.1177/09500179922117917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coulthard M, Walker A, Morgan A. People's perceptions of their neighbourhood and community involvement. London: The Stationary Office, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med 2007;357:370–9. 10.1056/NEJMsa066082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2249–58. 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fowler JH, Christakis NA. The dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. BMJ 2008;337:a2338 10.1136/bmj.a2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]