Abstract

Introduction

Women may experience anal sphincter anatomy changes after vaginal or Cesarean delivery. Therefore, accurate and acceptable imaging options to evaluate the anal sphincter complex (ASC) are needed. ASC measurements may differ between translabial (TL-US) and endoanal ultrasound (EA-US) imaging and between 2D and 3D ultrasound. The objective of this analysis was to describe measurement variation between these modalities.

Methods

Primiparous women underwent 2D and 3D TL-US imaging of the ASC six months after a vaginal birth (VB) or Cesarean delivery (CD). A subset of women also underwent EA-US measurements. Measurements included the internal anal sphincter (IAS) thickness at proximal, mid, and distal levels and the external anal sphincter (EAS) at 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions as well as bilateral thickness of the pubovisceralis muscle (PVM).

Results

433 women presented for US: 423 had TL-US and 64 had both TL-US and EA-US of the ASC. All IAS measurements were significantly thicker on TL-US than EA-US (all p<0.01), while EAS measurements were significantly thicker on EA-US (p<0.01). PVM measurements with 3D or 2D imaging were similar (p>0.20). On both TL-US and EA-US, there were multiple sites where significant asymmetry existed in left versus right measurements.

Conclusion

The ultrasound modality used to image the ASC introduces small but significant changes in measurements, and the direction of the bias depends on the muscle and location being imaged.

Keywords: anal sphincter, ultrasound, endoanal, translabial, postpartum

Background

Injury to the anal sphincter complex (ASC) during childbirth is a common complication of birth, and these injuries are now recognized as causing potentially long-lasting morbidity.1,2 Fecal incontinence (FI), a devastating and embarrassing disorder, often follows sphincter injury related to childbirth.3 While ultrasound is a vital tool in the diagnosis of anal sphincter pathology,4 29 sonograms would be needed to be performed on postpartum women without signs of sphincter injury to diagnosis and prevent one case of severe FI.5

Emerging ultrasound technologies have broadened options for pelvic floor imaging and may better detect ASC pathology after the birth of a child, but this technology also displays the wide range of variation in normal sphincter anatomy. Past studies have measured ASC anatomy in small cohorts of patients,6–8 but the heterogeneity of imaging methods and modalities (transvaginal, transperineal, and endoanal) makes the literature difficult to meaningfully analyze and is a barrier to establishing normal anatomic ASC dimensions in parous women. 4 It is expected that measurements of normal ASC anatomy would vary based on the modality of ultrasound used,4,6 but there is little information on the direction and magnitude of bias between modalities. Past studies have suggested that endoanal ultrasound (EA-US) of the ASC is the “gold standard” for evaluating the ASC as evaluated against MRI or surgical findings.9–11 However, recent studies indicate that the ASC can also be reproducibly evaluated with 3D translabial ultrasound (TL-US).11–16

Establishing normal measurements of the ASC for ultrasound evaluation should include measurements with both TL-US and EA-US imaging using 2D and 3D modalities. We have previously published measurements of the ASC on TL-US in a large cohort of women six months after the delivery of their first child by Cesarean delivery (CD) or vaginal birth (VB).17 In this study, we sought to compare our TL-US findings to EA-US as well as to compare measurements obtained with 2D and 3D imaging. We hypothesized that normal measurements would vary based on the modality used for imaging, and that different muscle locations may introduce different measurement bias based on the modality being used.

Methods

This study is a planned secondary assessment of data collected as part of a parent study evaluating postpartum pelvic floor changes following the delivery of a first child. Nulliparous, healthy women who presented to prenatal care with the University of New Mexico midwives were recruited prenatally and an additional cohort who delivered their first child by CD without entering the second stage of labor were recruited immediately postpartum. This study was approved by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Internal Review Board (IRB). Informed written consent was given by all participants.

Methods of this study have been described in prior publications.13,17,18 Labor and maternal characteristics were gathered at birth and included detailed examination of all lacerations to the genital tract sustained during delivery. Women with a second degree or more severe perineal laceration were evaluated by a second examiner to ensure that lacerations were graded appropriately. All third and fourth degree lacerations were repaired at the time of delivery, with standard repair methodology including identification and repair of the IAS with polygalactin sutures and repair of the EAS in an end-to-end or overlapping fashion with PDS suture.

All study participants were scheduled to undergo six month postpartum 2D and 3D TL-US and EA-US imaging of the ASC. Exams were performed in the lithotomy position. All exams were performed by one of the principal investigators (RH) or by a physician trained in Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery. All examiners were masked to the patients’ delivery history.

Our TL-US methodology has been previously described,13,17 and has displayed high inter-rater reliability.13 For both TL-US and EA-US imaging, the ASC was imaged in multiple planes, including proximal, mid, and distal levels of the ASC.19 The proximal level was the IAS plane just distal to the anal angle, the mid-level was the location at which the pubovisceralis muscle (PVM) could be seen at its thickest point passing posteriorly to the IAS, and the distal level was the level at which the IAS and EAS were optimally imaged together.

For TL-US, we acquired all 2D and 3D measurements and 3D volume sets using the GE E8 ultrasound system with the 5–9 MHz endovaginal transducer (Milwaukee, WI) or the Phillips IU22 with the 4–8 MHz endovaginal transducer (Bothell, WA). The endovaginal transducer was placed at the posterior introitus in a transverse plane, angling nearly perpendicularly to the floor, and the ASC was imaged in the multiple planes by changing the angle to image from superior to inferior. For EA-US imaging, we acquired all 2D and 3D measurements and 3D volume sets using the BK Medical Hawk system with the 10–16 MHz anorectal transducer (Peabody, MA). The transducer was placed in the rectum and 2D and 3D volume sets were obtained and stored in a Hawk hard drive. Each 2D and 3D volume set was stored in our imaging center’s picture archiving and communication system (PACS).

In both TL-US and EA-US, we performed a full survey of the IAS and EAS complex, including imaging of the PVM. The 2D TL-US transducer was rotated 90° from the axial plane to a mid-sagittal plane to acquire 3D volume sets. A 75 degree volume sweep was performed with high quality resolution (slow sweep). We describe 3D planes as relative to the anatomy being imaged, as is consistent with standard practice in diagnostic ultrasound imaging, and is described in this manner by other authors measuring the anal sphincter complex.6 3D volume sets were acquired in the midline sagittal plane (A Plane), and 3D ASC measurements were performed in the plane axial to the midline sagittal plane (B Plane). The coronal plane (C Plane) and the B Plane were used to manipulate the center reference point to correctly align the overall volume. The 3D volume set was then manipulated by X, Y, and Z axis rotations in order to optimize the planes in which to take the optimal measurements of the IAS/EAS complex at 12, 3, 6 and 9 o’clock positions in the transverse plane at proximal, mid and distal anal ASC levels. We produced a subset of short field of view (FOV) 2D and manipulated 3D planes in order to optimize the thickest transverse PVM cut, most optimally measured at the pivotal 4 and 8 o’clock locations at the mid IAS level.6,15 As noted in our previous publications,13,17 this protocol did not include a field of view that was meant to optimally image the insertion of the PVM into the pubic bone.

We defined sphincter interruption as a complete discontinuity in the sphincter at a specific location. Women with third or fourth degree lacerations at the time of delivery or complete IAS or EAS interruption on six month postpartum TL-US were included in the comparison of measurements between EA-US and TL-US imaging. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests. Categorical variables were compared with Chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test. The mean of four quadrants of the sphincter at each level for IAS and for EAS was calculated and these means were compared between TL-US and EA-US using paired T-tests. 2D versus 3D measurements and the left versus right side of the woman on sphincter and PVM measurements were also compared using paired T-tests. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS programming.

Results

Between July 2006 and December 2011, 782 women were consented prenatally and post-Cesarean delivery to participate, and 696 delivered at the University of New Mexico: 448 delivered by VB and 246 delivered by CD. Two women were deemed ineligible after recruitment due to having preterm vaginal births at <37 weeks gestation. There was a single forceps delivery, 25 vacuum deliveries (6% of VB), and eight episiotomies (2% of VB) in this study population. Ten percent of the CD patients were midwife patients transferred to physician care for CD; the rest of the CD group never entered the second stage of labor.17

Sixty-two percent (433/694) of eligible women presented for US imaging (299 VB and 134 CD) six months postpartum, and 423 of them had full imaging of the anal sphincters on TL-US (299 VB and 124 CD). Characteristics of this population presenting for US, including age, birth weight, and length of the second stage of labor, have been previously reported, with a mean age of 25 ± 5.6 years and a racial distribution of mostly Caucasian (n=187, 43%) and Hispanic (n=186, 43%) women.17 Women who presented for ultrasound had more years of education (13.99 ± 2.74 vs 13.53 ± 2.86 years, p =0.04) and were more likely to have undergone a VB (69 vs 56% VB, p <0.01) than women who did not matriculate for ultrasound imaging, but were otherwise similar in baseline characteristics. Of women who presented for US imaging, 64 women (36 VB and 28 CD) had full EA-US and TL-US measurements of the sphincters. Normative TL-US measurements of the ASC and comparison of measurements between VB and CD women are discussed in a prior publication on this cohort.17 The majority of women who presented for ultrasound declined endoanal imaging. Women who had full ultrasound measurements of the sphincters on both EA-US and TL-US were less likely to have had a VB (56% vs 73%, p=0.01), but were otherwise similar in demographics to women who only had TL-US measurements (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of women presenting for ultrasound: Women who had translabial ultrasound only versus women having both translabial and endoanal ultrasound

| Women Having Translabial Ultrasound Only N=359 |

Women Having Translabial and Endoanal Ultrasound N=64 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 25.4 ± 6.1 | 25.1 ± 5.5 | 0.7 |

| Education (Years) (mean ± SD) | 14.1 ± 2.7 | 13.5 ± 3.0 | 0.17 |

| Weight Gain in Pregnancy (Pounds) (mean ± SD) | 35.8 ± 14.9 | 32.9 ± 16.5 | 0.19 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) | 25.4 ± 5.7 | 24.9 ± 5.8 | 0.9 |

| Race (N(%)) | |||

| White | 156 (43) | 25 (39) | 0.71 |

| Hispanic | 154 (43) | 29 (45) | |

| Other | 49 (130) | 9 (14) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 10 (3) | 3 (5) | |

| African American | 15 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| Native American | 24 (7) | 5 (8) | |

| Vaginal birth (N(%)) | 263 (73) | 36 (56) | 0.01 |

| Tobacco Use (N(%)) | 26 (7) | 2 (3) | 0.41 |

| Baby Weight (grams) (mean ± SD) | 3241 ± 450 | 3119 ± 513 | 0.07 |

| Epidural (N(%)) | 219 (61) | 38 (59) | 0.78 |

| Oxytocin Use (N(%)) | 178 (50) | 39 (59) | 0.13 |

| Episiotomy (N(%)) | 3 (1) | 2 (3) | 0.12 |

Sphincter interruptions on ultrasound imaging at six months postpartum were rare (4 EAS separations and 36 IAS separations in 38 women, 33 VB and 5 CD). Four women had interruptions of the IAS and one woman had interruption of the EAS seen on endoanal imaging; for two of these women, the same muscle was found to be interrupted on translabial imaging. A single woman who underwent imaging in both modalities had discrepant readings; interruption of the EAS was seen on endoanal imaging, however, the translabial imaging recognized the IAS as interrupted but did see an interruption in the EAS.

Mean measurements differed between TL-US and EA-US measurements of the anal sphincter thickness averaged over the four quadrants, although these differences were small in magnitude (Table 2). The external sphincter was larger on EA-US as compared to TL-US, whereas all internal sphincter measurements were smaller on EA-US (all p<0.01).

Table 2.

Endoanal (EA-US) versus translabial (TL-US) measurement of the anal sphincter complex (ASC)

| EA-US (mean ± SD in mm) N=359 |

TL-US (mean ± SD in mm) N=64 |

Mean Difference by Paired T-test (EA-US minus TL-US in mm) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAS | ||||

| Proximal | 1.29 ± 0.49 | 2.07 ± 0.51 | −0.79 | <0.01 |

| Mid | 1.36 ± 0.59 | 2.10 ± 0.54 | −0.74 | <0.01 |

| Distal | 1.59 ± 0.52 | 2.18 ± 0.48 | −0.59 | <0.01 |

| EAS | 2.71 ± 1.41 | 1.95 ± 0.83 | +0.77 | <0.01 |

| PVM Right | 7.50 ± 1.44 | 6.81 ±1.60 | +0.69 | 0.69 |

| PVM Left | 7.35 ± 1.36 | 7.16 ± 1.76 | +0.18 | 0.18 |

There were 388 women who had both translabial 2D and 3D measurements of the PVM to compare by paired t-test. Translabial 3D imaging of the PVM yielded similar measurements of the PVM compared to translabial 2D imaging alone on both the right (7.06 mm vs. 6.97 mm, p=0.24) and left side (7.33 mm vs. 7.22 mm, p=0.21). There were 137 women who had both EA-US and TL-US imaging of the PVM. There were no significant differences between EA-US and TL-US measurements of the PVM thickness on the right (p=0.69) or the left (p=0.18).

When comparing left to right side of the woman for both modes of ultrasound, the right side of the distal IAS measured significantly thicker than the left (9 o’clock thicker than 3 o’clock) on EA-US, and this was also true for the mid and distal level of the IAS on TL-US (Table 3). The EAS measured thicker on the right side on TL-US (3.04 mm vs. 2.84 mm, p<0.01) and on EA-US imaging (3.78 mm vs. 3.66 mm, p<0.01). On TL-US imaging, the left PVM was thicker than the right for both 2D and 3D measurements (p<0.01).

Table 3.

Asymmetry (Left versus Right or 3 versus 6 o’clock) in sphincter measurements

| Right Side (9 o’clock) of Patient (mean ± SD) | Left Side (3 o’clock) of Patient (mean ± SD) | Mean Difference Paired T-Test (9 o’clock minus 3 o’clock or right minus left) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA-US thickness in mm | ||||

| Proximal IAS (N=62) | 1.37 ± 0.74 | 1.42 ± 0.59 | −0.06 | 0.34 |

| Mid IAS (N=62) | 1.47 ± 0.65 | 1.38 ± 0.69 | +0.09 | 0.010 |

| Distal IAS (N=63) | 1.79 ± 0.61 | 1.68 ± 0.59 | +0.12 | <0.01 |

| EAS (N=62) | 3.04 ± 1.80 | 2.84 ± 1.53 | +0.20 | 0.01 |

| TL-US thickness in mm | ||||

| Proximal IAS (N=421) | 2.22 ± 0.65 | 2.17 ± 0.63 | +0.04 | 0.01 |

| Mid IAS (N=423) | 2.36 ± 0.62 | 2.28 ± 0.62 | +0.09 | <0.01 |

| Distal IAS (N=417) | 2.37 ± 0.62 | 2.25 ± 0.61 | +0.12 | <0.01 |

| EAS (N=420) | 3.78 ± 1.70 | 3.66 ± 1.68 | +0.12 | <0.01 |

| PVM thickness in mm | ||||

| Translabial 2-D (N=404) | 6.97 ± 1.61 | 7.23 ± 1.67 | −0.27 | <0.01 |

| Translabial 3-D (N=411) | 7.01 ± 1.75 | 7.25 ± 1.86 | −0.25 | <0.01 |

| Endoanal (N=132) | 7.45 ± 1.46 | 7.31 ± 1.36 | +0.14 | 0.10 |

Discussion

We found small but significant differences in measurement of the ASC on EA-US versus TL-US in women six months after the birth of their first child; EA-US measured the EAS as larger and the IAS as smaller than TL-US in this cohort. The study also demonstrates that women tend to have thicker measurements of the anal sphincters on the right side of the body, regardless of whether imaging is translabial or endoanal, and the PVM measurements tend to be greater on the left. These data describe where and how clinicians can expect measurements to differ between imaging modalities. However, the measurement variation we found is small in magnitude and unlikely to be clinically significant, so these data would support clinicians using the modality that is best for their experience set and patient comfort.

EA-US has long been referred to as the “reference standard” for evaluation of these muscles. Endoanal ultrasound has been found to be comparable to MRI and has advantages in imaging certain planes.7,9,20,21 Recent investigations, based on small numbers of women, have demonstrated that 3D endoanal ultrasound can image the pelvic floor in motion, such as during pelvic floor contraction or Valsalva, allowing for evaluation of changes in the genital hiatus and organ descent.8,10 However, other studies find that TL-US can also be used examine these dynamic changes with notable reliability, and can demonstrate important findings such as post-surgical dynamic changes in the degree of pelvic organ descent.16,22 A recent study by Roos et al discussed the comparison of TL-US and EA-US for the evaluation of IAS and EAS defects in 161 postpartum women, but this study did not determine normative measurements or compare measurements between the modalities.9 Another study described findings in the same women with both endoanal and transperineal US and were able to see defects well on both types of imaging, although no measurements were taken or compared.23

A previous study from our institution has established the measurements for translabial US measurements of the anal sphincter complex in a large series, and these measurements were found to be highly reliable in a series of 60 women without pelvic floor disorders.13 This reliability of TL-US has also been established in evaluation of the levator musculature.24 Data from future studies and ongoing studies may confirm that the ease and comfort of TL-US is joined by reliability and accuracy equal to that of EA-US, but this is yet to be established. In this cohort of young, primiparous women, the majority of patient declined endoanal imaging, indicating that endoanal imaging may not be acceptable to many patients. The large number of women who had TL-US but did not agree to EA-US, and the sole woman who had an EAS defect recognized on one modality but not another precludes our commenting on which of these methods may be superior for sphincter defect recognition. However, we found that both modalities yield similar measurements of the ASC, although the direction of modality bias depends on the muscle being imaged.

There is debate as to whether asymmetries seen in ultrasound imaging are a product of transducer location, or may be a part of normal female anatomy. This study’s findings are consistent with endoanal MRI data demonstrating that the anterior portion of the sphincter in women may have less length.25 It has been suggested that these findings may be due to the endoanal ultrasound transducer’s circumferential stretch of the musculature, making these measurements unreliable, but the fact that this does not affect all quadrants equally is puzzling to investigators. Past studies have established that EA-US measurements of the IAS may also be unreliable, given the additional stretch of the IAS by the endoluminal transducer.26 There is some evidence that external compression of the perineum on TL-US may distort normal anatomy,27 and this effect would theoretically be confined to the 12 o’clock sphincter. TL-US measurements may also be altered by the change in angle involved in introital placement of the transducer. Our findings demonstrate that TL-US measured the IAS as significantly larger than on images obtained by EA-US. The EAS did not demonstrate this difference on EA-US imaging, although this may be due to the fact that the EAS is lies farther from an endoanal transducer. In fact, our study indicates that EA-US measurements of the EAS are significantly larger than on TL-US. This provides evidence that EA-US and TL-US have some biases that are not only merely due to mechanical distortions such as stretch of the muscle by the endoluminal transducer or pressure on the perineum from an introital transducer. However, the clinical significance of the measurement bias (less than half a millimeter) may be quite small, even with a highly accurate exam.

Our data join other evidence indicating that even normal female ASC anatomy is often asymmetrical. One past study demonstrated significantly more thinning of the IAS on the left side on EA-US imaging28, which is consistent with our findings of thicker right-sided muscle measurements in both TL-US and EA-US. Our study also found that the left PVM was thicker than the right for both 2D and 3D imaging, which may be due to the handedness of the examiners or due to the more common direction of the fetal occiput in births. Literature clarifying the role of levator injury or avulsion in pelvic floor pathology has been brought to light in the years since the completion of this study protocol. It has been well established that TL-US can excellently image the PVM and establish avulsion,8,22, 29 but there may be more injury or thinning of the PVM on one side as opposed to the other, with more thinning on the left side reported in a past study.30 These findings of left to right asymmetry could be due to our imaging methodology, asymmetrical sphincter or levator ani damage in the birthing process, or may be an unexpected part of normal female anatomy. With the ability to manipulate the 3D volume set, as in this protocol, measurement planes can be fine-tuned to best visualize asymmetry only if it truly exists. However, this protocol was only intended to measure thickness of the PVM and did not capture all clinically relevant injuries, such as levator avulsion. It would be recommended, given the asymmetry found in women from one side to the other, that imaging methodology seeking the represent the anatomy should always image both sides of the patient and use an ultrasound protocol that can fine-tune the image.

This study is limited by its single-institution design and inclusion of only primiparous, low-risk women, and may not be applicable to all populations. Also, most women in our study who presented for postpartum ultrasound did not allow the examiner to perform EA-US imaging, indicating that, for many women, this modality may be perceived as too uncomfortable and invasive. A strength of this study is the inclusion of a low-risk obstetric population, with relatively low rates of episiotomy, operative vaginal delivery, and severe laceration, making these measurements generalizable to many low morbidity postpartum patients. If EA-US is not a comfortable or available option for a woman, we have established that TL-US measurements will be similar to those found on EA-US, with bias in a small magnitude and the direction of bias depending on the muscle imaged. Providers should use the imaging modality that they are most experienced at performing and interpreting, and should consider patient comfort and the location of the suspected pathology in their imaging modality choice as well.

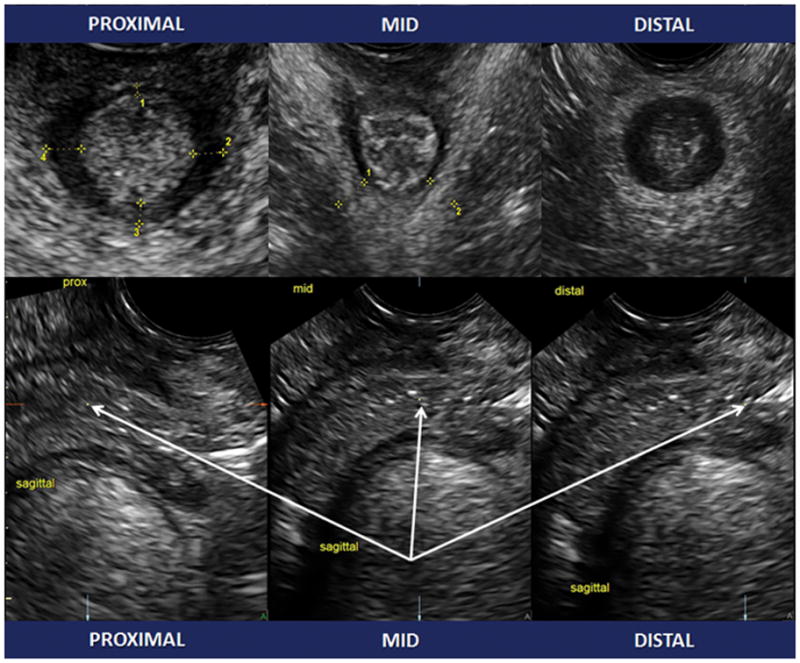

Figure 1.

Images of transverse views (above) and sagittal views (below) with center reference point at each of the three levels of the anal sphincter complex (ASC): proximal, mid, and distal.

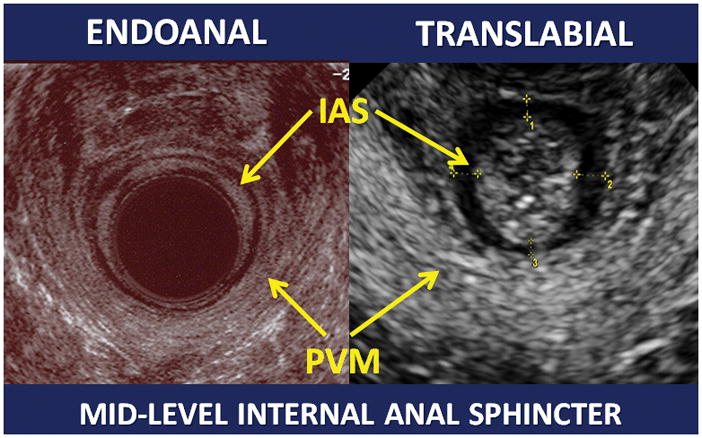

Figure 2.

Endoanal (left) and translabial (right) transverse ultrasound images of the distal anal sphincter complex, with the external anal sphincter (EAS) and internal anal sphincter (IAS) indicated by the arrows.

Figure 3.

Endoanal (left) and translabial (right) transverse ultrasound images of the mid-level anal sphincter complex, with the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and pubovisceralis muscle (PVM) indicated by the arrows.

Summary.

Differences in measurements of the anal sphincter complex between translabial and endoanal ultrasound imaging are small, and depend on the location of the muscle being measured.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement:

KV Meriwether: No conflicts of interest to disclose

RJ Hall: No conflicts of interest to disclose

LM Leeman: No conflicts of interest to disclose

L Migliaccio: No conflicts of interest to disclose

C Qualls: No conflicts of interest to disclose

RG Rogers: Chair DSMB for the Transform trial sponsored by American Medical Systems

Author Participation:

KV Meriwether: Data analysis, manuscript writing

RJ Hall: Study development, data collection/management, manuscript editing

LM Leeman: Protocol/project development, data collection/management, manuscript editing

L Migliaccio: Protocol/project development, manuscript editing

C Qualls: Data analysis, manuscript editing

RG Rogers: Protocol/project development, data collection/management, manuscript editing

Contributor Information

Dr. Kate V. MERIWETHER, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Dr. Rebecca J. HALL, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Dr. Lawrence M. LEEMAN, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Ms. Laura MIGLIACCIO, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Dr. Clifford QUALLS, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Dr. Rebecca G. ROGERS, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Citations

- 1.DeLancey JO. The hidden epidemic of pelvic floor dysfunction: achievable goals for improved prevention and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;192(5):1488–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel DA, Xu X, Thomason AD, Ransom SB, Ivy JS, DeLancey JO. Childbirth and pelvic floor dysfunction: an epidemiologic approach to the assessment of prevention opportunities at delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jul;195(1):23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberwalder M, Connor J, Wexner SD. Meta-analysis to determine the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter damage. Br J Surg. 2003 Nov;90(11):1333–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tubaro A, Koelbl H, Laterza R, Khullar V, de Nunzio C. Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor: where are we going? Neurourol Urodyn. 2011 Jun;30(5):729–34. doi: 10.1002/nau.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faltin DL, Boulvain M, Floris LA, Irion O. Diagnosis of anal sphincter tears to prevent fecal incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jul;106(1):6–13. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000165273.68486.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valsky DV, Yagel S. Three-dimensional transperineal ultrasonography of the pelvic floor: improving visualization for new clinical applications and better functional assessment. J Ultrasound Med. 2007 Oct;26(10):1373–87. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.10.1373. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander AA, Miller LS, Liu JB, Feld RI, Goldberg BB. High-resolution endoluminal sonography of the anal sphincter complex. J Ultrasound Med. 1994 Apr;13(4):281–4. doi: 10.7863/jum.1994.13.4.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein MM, Jung SA, Pretorius DH, Nager CW, den Boer DJ, Mittal RK. The reliability of puborectalis muscle measurements with 3-dimensional ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jul;197(1):68.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roos AM, Abdool Z, Sultan AH, Thakar R. The diagnostic accuracy of endovaginal and transperineal ultrasound for detecting anal sphincter defects: The PREDICT study. Clin Radiol. 2011 Jul;66(7):597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen AF, Nyhuus B, Nielsen MB, Christensen H. Three-dimensional anal endosonography may improve diagnostic confidence of detecting damage to the anal sphincter complex. Br J Radiol. 2005 Apr;78(928):308–11. doi: 10.1259/bjr/72038963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdool Z, Sultan AH, Thakar R. Br J Radiol. Ultrasound imaging of the anal sphincter complex: a review. 2012 Jul;85(1015):865–75. doi: 10.1259/bjr/27314678. Epub 2012 Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valsky DV, Messing B, Petkova R, Savchev S, Rosenak D, Hochner-Celnikier D, Yagel S. Postpartum evaluation of the anal sphincter by transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound in primiparous women after vaginal delivery and following surgical repair of third-degree tears by the overlapping technique. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Feb;29(2):195–204. doi: 10.1002/uog.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall RJ, Rogers RG, Saiz L, Qualls C. Translabial ultrasound assessment of the anal sphincter complex: normal measurements of the internal and external anal sphincters at the proximal, mid-, and distal levels. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007 Aug;18(8):881–8. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0254-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang WC, Yang SH, Yang JM. Three-dimensional transperineal sonographic characteristics of the anal sphincter complex in nulliparous women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Aug;30(2):210–20. doi: 10.1002/uog.4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JH, Pretorius DH, Weinstein M, Guaderrama NM, Nager CW, Mittal RK. Transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound in evaluating anal sphincter muscles. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Aug;30(2):201–9. doi: 10.1002/uog.4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstein MM, Pretorius DH, Jung SA, Nager CW, Mittal RK. Transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound imaging for detection of anatomic defects in the anal sphincter complex muscles. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Feb;7(2):205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meriwether KV, Hall RJ, Lawrence L, Migliaccio L, Qualls C, Rogers RG. Postpartum translabial 2D and 3D ultrasound measurements of the anal sphincter complex in primiparous women delivering by vaginal birth versus Cesarean delivery. International Urogynecology Journal. 2014 Mar;25(3):329–36. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers R, Leeman L, Borders N, Qualls C, Fullilove A, Teaf D, Hall R, Bedrick E, Albers L. Contribution of the second stage of labour to pelvic floor dysfunction: a prospective cohort comparison of nulliparous women. BJOG. 2014 Feb; doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delancey JO, Toglia MR, Perucchini D. Internal and external anal sphincter anatomy as it relates to midline obstetrical lacerations. Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Dec;90(6):924–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00472-9. Epub ahead of print 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietz HP. Pelvic floor ultrasound: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Apr;202(4):321–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rociu E, Stoker J, Eijkemans MJ, Schouten WR, Laméris JS. Fecal incontinence: endoanal US versus endoanal MR imaging. Radiology. 1999 Aug;212(2):453–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.2.r99au10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braekken IH, Majida M, Ellstrøm-Engh M, Dietz HP, Umek W, Bø K. Test-retest and intra-observer repeatability of two-, three- and four-dimensional perineal ultrasound of pelvic floor muscle anatomy and function. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008 Feb;19(2):227–35. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roche B, Deléaval J, Fransioli A, Marti MC. Comparison of transanal and external perineal ultrasonography. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(7):1165–70. doi: 10.1007/s003300000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Speksnijder L, Rousian M, Steegers EA, Van Der Spek PJ, Koning AH, Steensma AB. Agreement and reliability of pelvic floor measurements during contraction using three-dimensional pelvic floor ultrasound and virtual reality. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Jul;40(1):87–92. doi: 10.1002/uog.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rociu E, Stoker J, Eijkemans MJ, Lameris JS. Normal anal sphincter anatomy and age- and sex-related variations at high-spatial-resolution endoanal MR imaging. Radiology. 2000 Nov;217(2):395–401. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.2.r00nv13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayooran V, Deen KI, Wijesinghe PS, Pathmeswaran A. Endosonographic characteristics of the anal sphincter complex in primigravid Sri Lankan women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005 Sep;90(3):245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Titi MA, Jenkins JT, Urie A, Molloy RG. Perineum compression during EAUS enhances visualization of anterior anal sphincter defects. Colorectal Dis. 2009 Jul;11(6):625–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starck M, Bohe M, Fortling B, Valentin L. Endosonography of the anal sphincter in women of different ages and parity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Feb;25(2):169–76. doi: 10.1002/uog.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ismail SI, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Unilateral coronal diameters of the levator hiatus: baseline data for the automated detection of avulsion of the levator ani muscle. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Sep;36(3):375–8. doi: 10.1002/uog.7634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoyte L, Jakab M, Warfield SK, Shott S, Flesh G, Fielding JR. Levator ani thickness variations in symptomatic and asymptomatic women using magnetic resonance-based 3-dimensional color mapping. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Sep;191(3):856–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]