Abstract

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a heterozygous monogenic diabetes; more than 13 disease genes have been identified. However, the pathogenesis of MODY is not fully understood, because the pancreatic β-cells of the patients are inaccessable. Therefore, we attempted to establish MODY patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (MODY-iPS) cells to investigate the pathogenic mechanism of MODY by inducing pancreatic β-cells. We established MODY5-iPS cells from a Japanese patient with MODY5 (R177X), and confirmed that MODY5-iPS cells possessed the characteristics of pluripotent stem cells. In the course of differentiation from MODY5-iPS cells into pancreatic β-cells, we examined the disease gene, HNF1B messenger ribonucleic acid. We found that the amount of R177X mutant transcripts was much less than that of wild ones, but they increased after adding cycloheximide to the medium. These results suggest that these R177X mutant messenger ribonucleic acids are disrupted by nonsense-mediated messenger ribonucleic acid decay in MODY-iPS cells during the developmental stages of pancreatic β-cells.

Keywords: Diabetes, Maturity-onset diabetes of the young, Pluripotent stem cells

Introduction

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a monogenic form of diabetes that arises from one or more mutations in a single gene, and 13 disease genes for MODY have been identified1; for example, the disease gene of MODY5 is HNF1B1. Each MODY is presumably caused by dysfunction of pancreatic β-cells as a result of mutations in one of those genes. However, pancreatic β-cells of the patients are not easily or ethically available for experiments. Therefore, the molecular mechanisms underlying MODY in humans are largely unknown.

Today, the number of reports describing the generation of disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) cells is increasing2–4, and, very recently, establishment of Caucasians MODY patient-derived iPS cells has been reported (MODY-iPS cells)5,6. Because insulin sensitivity and insulin responses differ among Africans, Caucasians and East Asians7, the genetic background should be considered when investigating the pathophysiology of diabetes. Therefore, the establishment of MODY-iPS cell lines from various populations is vital for completely analyzing the pathogenesis of MODY.

In the present research, we established MODY5 (R177X)-iPS cells from a Japanese patient using non-integrating Sendai virus; MODY5 (R177X)-iPS cells had mutations leading to a premature termination codon (PTC). We found for the first time that MODY genes messenger ribonucleic acids (mRNAs) with PTC were degraded by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) during differentiation from MODY-iPS cells to pancreatic β-cells.

Material and Methods

Generation of MODY-iPS Cells

Skin fibroblasts were obtained from a MODY5 patient by a 5-mm punch biopsy at Tokyo Women's Medical University after written informed consent. We purchased healthy women's fibroblasts from Lonza (Verviers, Belgium) as a control. Aliquots of 106 cells of these control and MODY5-patient skin fibroblasts were transduced with hSOX2, hOCT3/4, hKLF and hC-MYC using SeV (MBL, Nagano, Japan) overnight. The cells were washed and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented 10% fetal bovine serum for 6 days. Then Sev-infected fibroblasts were seeded on mitomycin-treated mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells; the next day, the medium was replaced by hiPS medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium/F'12 supplemented with 20% knockout serum replacement, 2 mmol/L l-glutamine, 0.5× penicillin/streptomycin, 1× non-essential amino acids, 55 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol and 7.5 ng/mL FGF2). Then, 3–4 weeks later, primary hiPS colonies appeared, and we transferred each colony onto mitomycin-treated SNL feeder cells. These hiPS colonies were maintained on mitomycin-treated SNL feeder cells and enzymatically passaged using CTK solution at 1:5–1:8 once a week. In the present study, three different control or MODY-iPS cell lines were used, respectively. The experiments were carried out with the approval of the ethical committees in Tokyo Women's Medical University and the National Center for Global Health and Medicine.

Detailed Materials and Methods of the items are described in the Data S1.

Results

Establishment of MODY5-iPS Cells

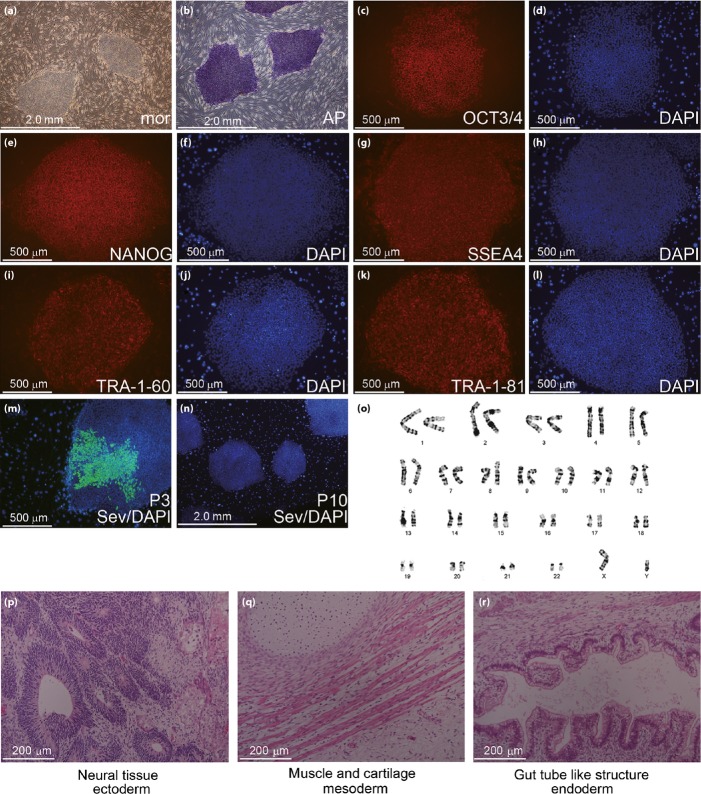

We established MODY-iPS cells using SeV from s Japanese MODY5 patient who had the R177X disease variant, and clinical features were previously characterized8,9. Although the SeV genome was present in the cytoplasm of the MODY5-iPS colonies at passage 3, we confirmed the complete shedding of the SeV genome by passage 10 by immunocytochemistry (Figure 1m) or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR; data not shown), indicating that these cells were transgene-free. We used MODY5-iPS cells more than 10 passages for experiments. The MODY5-iPS cells expressed pluripotency markers, such as OCT3/4, NANOG, SSEA4, TRA-1-60 and TRA-1-81, and had alkaline phosphatase activity (Figures 1b–l and S1b–l). Teratoma derived from MODY5-iPS and control hiPS cells contained three germ layers; ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm (Figures 1p–r and S1m–o). We confirmed that the karyotypes of the control and MODY 5-iPS cells were all normal (Figures 1o and S1p).

Figure 1.

Characterization of pluripotency of maturity-onset diabetes of the young 5-induced pluripotent stem (MODY5-iPS) cells. (a) Morphology of MODY5-iPS cells. (b) Alkaline phosphatase staining. (c–n) Immunocytochemistry for pluripotency markers. (c) OCT3/4; (e) NANOG; (g) SSEA4; (i) TRA-1-60; (k) TRA-1-81; (d, f, h, j, l) DAPI; (m) SeV, passage 3 (n) SeV, passage 10; (o) karyotype analysis by the G-band method; (p–r) teratoma derived from MODY1-iPS cells; (p) ectoderm – neural tissue; (q) mesoderm – muscle and cartilage; and (r) endoderm – gut tube-like structure.

Detection of Disease Gene mRNAs during Differentiation from MODY-iPS Cells into β-Like Cells

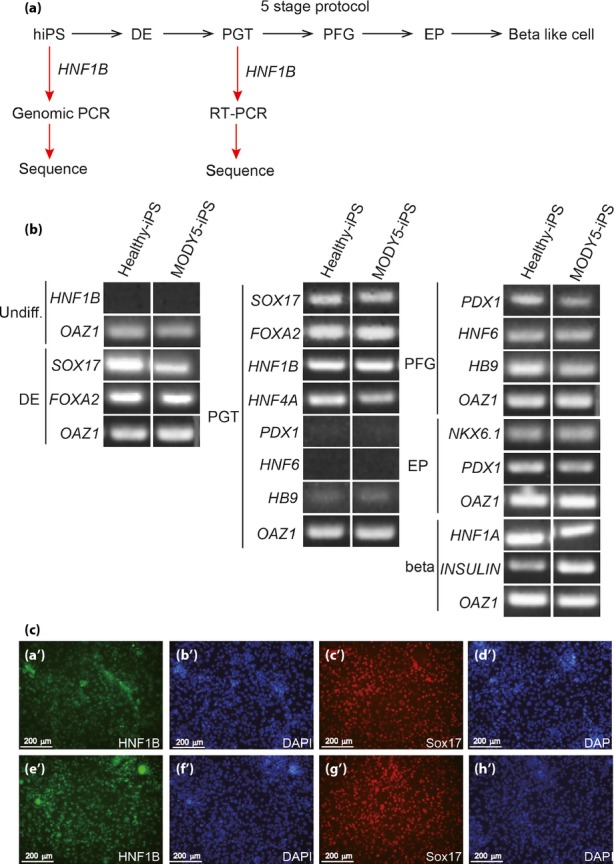

The disease gene of MODY5 is HNF1B. Expression of HNF1B was reported at the primitive gut tube stage during pancreatic β-cell development10,11. To detect HNF1B mRNA, control or MODY-iPS cells were differentiated into pancreatic β-cells using five-stage protocols10, and expression of marker genes for each stage was investigated by RT–PCR (Figure 2a,b). We confirmed that HNF1B mRNA as well as Sox17, FoxA2 and HNF4A mRNA were expressed at the primitive gut tube stage (Figure 2b). Immunocytochemistry showed that both control and MODY5-iPS cells differentiated into the primitive gut tube at the same level, because more than 90% of the cells were positive for HNF1B and Sox17 (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Differentiation of pancreatic β-cells from maturity-onset diabetes of the young 5-induced pluripotent stem (MODY5-iPS) cells. (a) Scheme of the differentiation process and cloning of disease genes. Definitive endoderm (DE), primitive gut tube (PGT), posterior foregut (PFG) and endocrine progenitor (EP). (b) Expression of marker genes for each stage by reverse transcription polymerase chain reactions (RT–PCR). Undifferentiation (undiff). OAZ1 is a housekeeping gene used as a loading control. (c) Immunocytochemistry of control or MODY5-IPS cells at PGT. (a'–d’) control iPS cells. (e’–h’) MODY5-iPS cells. (a’, e’) HNF1B: green, (b’, d’, f’, h’) DAPI: blue, (c’, g’) SOX17: red.

R177X Mutant mRNA Are Destroyed in Differentiated MODY-iPS Cells and Restored by Treatment with Cycloheximide

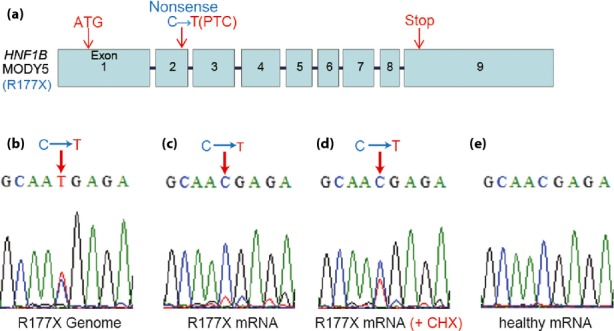

The mutation site of our MODY5 patient was exon 2 of HNF1B and caused PTC (Figure 3a), which is regarded as a tag of mRNA degradation by NMD12,13. Therefore, we amplified disease gene mRNA by RT–PCR and sequenced them. We confirmed that two bold signals with almost the same strength (C, wild and T, mutant) were present at the mutation site of the genomic sequence of the MODY5-iPS cell (Figure 3b). In contrast to the genomic sequence, one definite signal (C) derived from wild mRNA existed at the mutation site, whereas the signal (T) of R177X mutant mRNA was very weak (Figure 3c), showing that the R177X mutant mRNA might be decayed by the NMD pathway. To confirm this, differentiated MODY-iPS cells were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit NMD. Cycloheximide treatment clearly enhanced the sequence signal of R177X mutant mRNAs compared with non-treated samples (Figure 3c,d). We also confirmed that the sequence of HNF1b mRNA derived from control iPS cells had only clear wild-type transcript signals (Figure 3e).

Figure 3.

Detection of R177X mutation in genomic deoxyribonucleic acid and messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA). (a) Genomic structure of HNF1B in the maturity-onset diabetes of the young 5 (MODY5) patient. The original start and stop codons existed in exons 1 and 9, respectively. In the case of the R177X mutation, a nonsense mutation was present at exon 2 (C is replaced by T) leading to a premature termination codon (PTC). (b–e) Sequence data for the HNF1B gene and transcripts of control or MODY5-induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells at the primitive gut tube stage. (b) Genomic sequence data for the MODY5-iPS cells near the mutation site. (c) Sequence data cloned from transcripts derived from MODY5-iPS cells, (d) cycloheximide (CHX)-treated MODY5-iPS cells and (e) control iPS cells.

Discussion

Recently, Caucasian MODY-iPS cells were established by two groups5,6. However, MODY-iPS cells from Asian patients have never been reported. In the present research, we reported the establishment of MODY-iPS cells from a Japanese MODY5 patient who had the R177X mutation. Among MODY-iPS cells previously established, only MODY2-iPS cells have been used to examine the function of disease gene encoding glycolytic enzyme glucokinase at β-like cells6. We examined the disease gene mRNA encoding transcription factor HNF1B, and confirmed disruption of R177X mutant mRNA with PTC during the developmental process of pancreatic β-cells from MODY-iPS cells for the first time. Although destruction of several MODY3 and MODY5 (not including R177X) mutant mRNAs with PTC was previously reported using ectopic transcripts artificially made from Epstein–Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cells or tubule cells14,15, our results clearly showed that a mutant transcript with PTC is rapidly destroyed by NMD during the developmental stages of pancreatic β-cells, before the onset of MODY.

Thus, MODY-iPS cell technologies make it possible to obtain actual cells expressing MODY genes by differentiating MODY-iPS cells to pancreatic β-cells. Further study will be required for understanding the pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wataru Nishimura and Takao Nammo, Diabetes Research Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, for fruitful discussions. The authors are grateful to Dr BLS Pierce (University of Maryland University College) for editorial work in the preparation of this article. We also thank Professor Makoto Kawashima in the Department of Dermatology, Tokyo Women's Medical University, for carrying out the skin biopsies. This work was supported by a grant from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (24A115) to HO, a Grant-in-Aid (26860272) for Young Scientists (B) from the JSPS to SGY, and was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid (22510214) for Scientific Research from the MEXT to NI.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 | Characterization of pluripotency of control cells.

Data S1 | Supporting materials and methods.

References

- 1.Bonnefond A, Philippe J, Durand E, et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing and High Throughput Genotyping Identified KCNJ11 as the Thirteenth MODY Gene. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee G, Papapetrou EP, Kim H, et al. Modeling pathogenesis and treatment of familial dysautonomia using patient-specific iPSc. Nature. 2009;461:402–408. doi: 10.1038/nature08320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cauvajal-Vergara X, Sevilla A, D'Souza SL, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465:808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature09005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teo AKK, Windmueller R, Johansson BB, et al. Derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with maturity onset diabetes of the young. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:5353–5356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C112.428979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hua H, Shang L, Martinez H, et al. iPSC-derived beta cells model diabetes due to glucokinase deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3146–3153. doi: 10.1172/JCI67638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Kodama K, Tojjar D, Yamada S, et al. Ethnic Differences in the Relationship Between Insulin Sensitivity and Insulin Response. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1789–1796. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horikawa Y, Iwasaki N, Hara M, et al. Mutation in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta gene (TCF2) associated with MODY. Nat Genet. 1997;17:384–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki N, Ogata M, Tomonaga O, et al. Liver and kidney function in Japanese patients with maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2144–2148. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.12.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maehr R, Chen S, Snitow M, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15768–15773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906894106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Amour K, Bang AG, Elizaer S, et al. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nbt1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhuvanagiri M, Schlitter AM, Hentze MW, et al. NMD: RNA biology meets human genetic medicine. Biochem J. 2010;430:365–377. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoenberg DR, Maquat LE. Regulation of cytoplasmic mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:246–259. doi: 10.1038/nrg3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harries LW, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. Messenger RNA Transcripts of the hepatocyte Nuclear Factor-1A Gene Containing Premature Termination Codons Are Subject to Nonsense-Mediated Decay. Diabetes. 2004;53:500–504. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harries LW, Bingham C, Bellanne-Chantelot C, et al. The position of premature termination codons in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta gene determines susceptibility to nonsense-mediated decay. Hum Genet. 2005;118:214–224. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 | Characterization of pluripotency of control cells.

Data S1 | Supporting materials and methods.