Abstract

The complement system and the Toll-like (TLR) co-receptor CD14 play important roles in innate immunity and sepsis. Tissue factor (TF) is a key initiating component in intravascular coagulation in sepsis, and long pentraxin 3 (PTX3) enhances the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced transcription of TF. The aim of this study was to study the mechanism by which complement and CD14 affects LPS- and Escherichia coli (E. coli)-induced coagulation in human blood. Fresh whole blood was anti-coagulated with lepirudin, and incubated with ultra-purified LPS (100 ng/ml) or with E. coli (1 × 107/ml). Inhibitors and controls included the C3 blocking peptide compstatin, an anti-CD14 F(ab′)2 antibody and a control F(ab′)2. TF mRNA was measured using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and monocyte TF surface expression by flow cytometry. TF functional activity in plasma microparticles was measured using an amidolytic assay. Prothrombin fragment F 1+2 (PTF1.2) and PTX3 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The effect of TF was examined using an anti-TF blocking antibody. E. coli increased plasma PTF1.2 and PTX3 levels markedly. This increase was reduced by 84–>99% with compstatin, 55–97% with anti-CD14 and > 99% with combined inhibition (P < 0·05 for all). The combined inhibition was significantly (P < 0·05) more efficient than compstatin and anti-CD14 alone. The LPS- and E. coli–induced TF mRNA levels, monocyte TF surface expression and TF functional activity were reduced by > 99% (P < 0·05) with combined C3 and CD14 inhibition. LPS- and E. coli–induced PTF1.2 was reduced by 76–81% (P < 0·05) with anti-TF antibody. LPS and E. coli activated the coagulation system by a complement- and CD14-dependent up-regulation of TF, leading subsequently to prothrombin activation.

Keywords: CD14, coagulation, complement, Escherichia coli, lipopolysaccharide, sepsis, whole blood

Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening disease that affects 750 000 people in the United States each year 1, and may be associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), multi-organ failure and death. Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory process that involves immunocompetent cells, the complement system and coagulation.

Tissue factor (TF) is not usually expressed by cells that contact the blood, and TF is normally not found in blood, although very low TF levels have been detected in plasma microparticles in healthy people 2. Endotoxin and several cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)−1β, activate monocytes and enhance TF surface expression 3. Long pentraxin 3 (PTX3) is an acute-phase protein that enhances lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced TF transcription 3,4. Immunothrombosis is caused by thrombocyte activation and thrombus formation initiated by immune competent cells after activation by pathogens 5. Thrombosis may limit inflammation and the spread of pathogens. Immunothrombosis dysregulation leads to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) 5. Warr et al. showed that enhanced TF surface expression is important in sepsis-induced DIC 6. Therefore, TF surface expression inhibition may reduce the occurrence of DIC during sepsis.

LPS is the main cell wall component in Gram-negative bacteria. LPS binds to pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 7. Myeloid differentiation protein 2 (MD-2) binds to the extracellular region of TLR-4 and is required for intracellular signalling 8. CD14 transports LPS from LPS binding protein (LBP) to TLR-4 9, and is also a co-receptor for TLR-1, -2, -3, -6, -7 and -9 10.

Complement is activated by LPS only at very high concentrations in human whole blood compared with whole Escherichia coli (E.coli) bacteria 11. E. coli bacteria activate both the classical and alternative pathways of complement 12. We have shown previously that the E. coli-induced TF expression in human whole blood monocytes is mainly complement- and CD14-dependent 13. Complement and CD14 inhibition may therefore reduce the E. coli-induced coagulation mediated by TF. The role of complement and CD14 on pure LPS-induced TF has, however, not been studied previously in the human whole blood model using lepirudin as anti-coagulant.

Because complement and CD14 are key molecules and co-operate in innate immunity 14,15, we hypothesized previously that the combined upstream inhibition of complement and CD14 may limit sepsis-induced inflammation and coagulation 14. Combined complement and CD14 inhibition inhibits E. coli-induced cytokine release efficiently 16,17. Other studies have shown that combined inhibition also inhibits efficiently complement receptor 3 (CR3) up-regulation, phagocytosis and oxidative burst 11,16. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of selective or combined inhibition of complement and CD14 in LPS- or E. coli-induced coagulation and PTX3 release in fresh human whole blood.

Materials and methods

Whole blood experiments

Whole blood experiments were performed with blood from 10 donors, as described previously 12. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Northern Norway Regional Health Authority. All equipment, tips and solutions were endotoxin-free. Polypropylene tubes (4·5 ml; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) with lepirudin (Refludan®; Celgene, Uxbridge, UK; 50 mg/l) were used as anti-coagulant. Fresh blood (five parts) was distributed immediately into polypropylene tubes containing Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, one part), inhibitors or controls (one part). The samples were preincubated for 8 min at 37°C. Immediately after the preincubation, PBS with CaCl2 and MgCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), heat-inactivated E. coli (strain LE392, ATCC 33572; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) or ultra-pure LPS (100 ng/ml) from E. coli 0111 (LPS-EB Ultrapure; InvivoGen, Eugene, OR, USA) was added. The time zero (T0) sample was processed immediately after blood sampling. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the blood was distributed into three different tubes. Citrate solution [3·2%, 1: 9 (v/v)] was added immediately to the tubes before flow cytometric analysis. Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA, 10 mM) was added to the tubes for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and mRNA analysis. No additive was used in the tubes prior to TF functional analysis in plasma microparticles. The tubes were centrifuged for 15 min at 3220 g at 4°C. The plasma was stored at −80°C until it was analysed. The cell pellets were lysed using 1× Nucleic Acid Purification Lysis Solution (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK), and the lysates were stored at −80°C until mRNA analysis was performed.

Inhibitors and antibodies

Anti-CD14 F(ab′)2 (LPS concentration < 3·9 EU/ml) was obtained from Diatec Monoclonals (Oslo, Norway). The C3 convertase inhibitor compstatin (lot CP20) and its corresponding control peptide, synthesized as described previously 18, was a kind gift from Professor John Lambris. Compstatin was used at a final concentration of 20 µM. The fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human TF antibody (product no. 4508CJ, clone VD8) was obtained from American Diagnostica, Inc. (Stamford, CT, USA). The isotype-matched control anti-HIV-1 gp120 (clone G3-519) was a kind gift from M. Fung (Tanox Inc., Houston, TX, USA). The monoclonal mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 blocking antibody (Sekisui 4509) against human TF [a-TF monoclonal antibody (mAb)] was obtained from American Diagnostica, Inc.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

Prothrombin fragment F 1+2 (PTF1·2) plasma levels were measured using the Enzygnost® F1 + 2 (monoclonal) kit (Dade Behring, Marburg GmbH, Germany). Human PTX3 was analysed using an ELISA kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Soluble TCC levels (sC5b-9) were measured using a mAb against a specific C9 neoepitope in the TCC complex, as described previously 19. An MRX microplate reader (Dynex Technologies, Denkendorf, Germany) was used to measure optical densities. Cytokines were analysed using the Bio-Plex Human Cytokine 27-plex cytokine multiplex panel from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA).

Real-time-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR) of tissue factor mRNA levels

Total RNA was isolated from cell lysates using total RNA chemistry and the AB6100 nucleic acid prep station (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The RNA concentrations were analysed using a NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 50 ng of total RNA using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit and a 2720 Thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) and was stored at −80°C. The TF mRNA levels were measured using the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix reagents and predeveloped TaqMan® gene expression assays. TF (Hs00175225_m1) was the target gene, and human beta-2-microglobulin (B2M, assay ID 4326319E; Applied Biosystems) was used as a reference gene. We used 3 µl cDNA for RT–qPCR, and the samples were analysed in triplicate. The relative TF mRNA levels were measured using the comparative delta-delta Ct method. The TF mRNA levels in the samples after 2-h incubation with PBS only were set to 1 and used to calibrate the results.

Flow cytometric analysis of TF surface expression

Monocyte TF surface expression was analysed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). Whole blood (12·5 µl) was stained with FITC-conjugated anti-human TF (product no. 4508CJ, clone VD8; American Diagnostica, Inc.) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD14 (Becton Dickinson) antibodies. IgG1 FITC (BD 345815) was used as an isotype-matched control. The blood was incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Easy lyse (S2364, Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) was added to the blood and incubated for 15 min at room temperature to lyse the red blood cells. PBS with 0·1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin was used to wash and resuspend the leucocytes. Monocytes and granulocytes were gated in a PE/side-scatter (SSC) dot-plot. The results are shown as the median fluorescent intensity (MFI).

TF functional activity in plasma microparticles

TF functional activity in plasma microparticles was analysed as described previously by Engstad et al. 20. Platelet-poor plasma was centrifuged at 40 000 g for 90 min (4°C) to isolate the microparticles. Thereafter, 200 µl of 0·15 M NaCl was used to resuspend the microparticles. TF functional activity was measured in a two-stage amidolytic assay. The assay was based on the ability of TF to accelerate the activation of FX by FVII. Further, FXa in the presence of FVa activates prothrombin to form thrombin 20.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 6·0 from GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. Any skewed results were transformed logarithmically. The results were analysed using paired Student’s t-test between baseline samples with PBS only and samples with LPS [panel (a) in the figures] or E. coli [panel (b) in the figures]. One-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (anova) with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare samples treated with inhibitors and their corresponding LPS- or E. coli-positive controls. One-way repeated-measures anova with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to analyse differences between combined and single inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD14. The results were considered statistically significant when P < 0·05. The background activation (negative control) was subtracted from the positive control and the intervention groups before calculating the percentage inhibition by the different inhibitors.

Results

The effects of selective and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on LPS- and E. coli-induced PTF1.2 level

LPS- and E. coli-induced coagulation was assessed by measuring PTF1·2 levels. Incubation with ultra-pure E. coli LPS (100 ng/ml) for 2 h increased the PTF1·2 level by 8·6-fold, from 0·65 nmol/l in the PBS control to 5·6 nmol/l (Fig. 1a). We then examined the role of complement by adding the selective C3 convertase inhibitor compstatin. The role of CD14 was evaluated by adding an anti-CD14 blocking F(ab′)2. The LPS-induced PTF1·2 levels were reduced efficiently and significantly (P < 0·05) by selective complement and CD14 inhibition to 0·96 and 0·97 nmol/l, respectively.

Figure 1.

The effect of selective complement and CD14 inhibition on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and Escherichia coli (E.coli)-induced coagulation, as assessed by measuring prothrombin fragment F 1+2 (PTF1.2) levels in the plasma. Fresh human whole blood was incubated for 2 h with LPS (100 ng/ml) (a) or E. coli (1 × 107/ml) (b) in the presence of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), anti-CD14 F(ab′)2 (aCD14, 10 µg/ml), compstatin (Comp., 20 µM), compstatin and anti-CD14 F(ab’)2 combined (Comp. + aCD14) or a control peptide (Ctrl.). PTF1.2 levels were analysed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and are shown as nmol/l. The values are given as the means with 95% confidence interval (CI) from separate experiments with different blood donors (n=6). #P < 0·05: comparison between phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone and LPS (a) or E. coli (b). * P < 0·05: comparison between LPS (a) or E. coli (b) and the inhibitors/controls. §P < 0·05: selective comparison between single and combined inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD-14. T0 represents sample obtained at time zero.

Incubation with E. coli (1 × 107/ml) for 2 h enhanced PTF1·2 levels from 1·5 nmol/l in the PBS control to 12·0 nmol/l (Fig. 1b). Compstatin significantly (P < 0·05) reduced PTF1·2 levels to 3·3 nmol/l, anti-CD14 significantly (P < 0·05) reduced the PTF1.2 levels to 6.3 nmol/l and combined complement and CD14 inhibition significantly (P < 0·05) reduced PTF1·2 levels to 0·79 nmol/l. The combined inhibition was significantly (P < 0·05) more efficient than the inhibition with anti-CD14 and compstatin alone.

The effect of selective and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on LPS- and E. coli-induced TF mRNA up-regulation

TF mRNA levels were measured by RT–qPCR. The results are given as the relative quantity (RQ) of mRNA to the mRNA level in the control sample, which was incubated with PBS only for 2 h and set to 1. LPS increased the TF mRNA levels significantly (P < 0·05) by 5·9-fold. LPS-induced TF mRNA up-regulation was reduced significantly (P < 0·05) to 0·3 RQ by anti-CD14 and compstatin combined (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

The effect of selective complement and CD14 inhibition on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and Escherichia coli (E.coli)-induced tissue factor (TF) mRNA up-regulation. LPS (100 ng/ml) (a) or E. coli (1 × 107/ml) (b) was added to whole blood and incubated for 2 h. The inhibitors and controls that were added are described in the legend for Fig. 1. TF mRNA was measured using real-time–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR). TF mRNA levels in the samples without stimulus and inhibitor [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) control] were set to 1 and used to calibrate the assay. The results are given as the relative quantity (RQ) to the calibrator. The values are given as the means with 95% confidence interval (CI) from separate experiments with different blood donors (n = 6). #P < 0·05: comparison between PBS alone and with LPS (a) or E. coli, (b). *P < 0·05: comparison between LPS (a) or E. coli (b) and the inhibitors/controls. §P < 0·05: selective comparison between single and combined inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD14.

Incubation with E. coli increased the TF mRNA levels by 6·5-fold after 2 h of incubation (Fig. 2b). The combined complement and CD14 inhibition was most efficient, reducing the TF mRNA level significantly (P < 0·05) to 0·9 RQ. Compstatin reduced the E. coli-induced TF mRNA levels significantly (P < 0·05) to 1·9 RQ. In comparison, anti-CD14 alone did not reduce E. coli-induced TF mRNA levels.

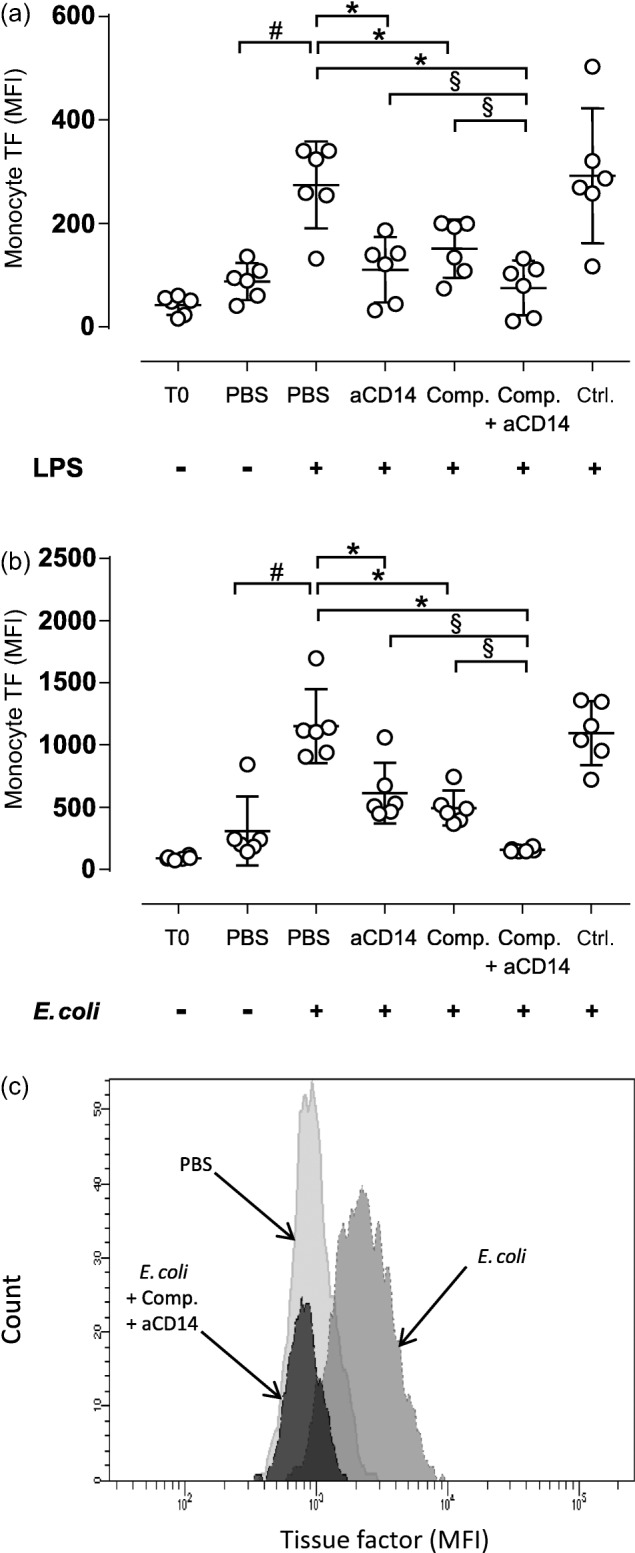

The effect of selective and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on LPS- and E. coli-induced monocyte TF surface expression

Whole blood monocyte TF surface expression was measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 3). Incubation with LPS increased TF surface expression by 3·1-fold, from 88 MFI in the PBS control to 275 MFI after 2 h of incubation (Fig. 3a). The combined inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD14 was most efficient, significantly (P < 0·05) reducing LPS-induced TF surface expression to 76 MFI. Both anti-CD14 and compstatin alone significantly (P < 0·05) reduced the LPS-induced TF surface expression to 110 and 151 MFI, respectively.

Figure 3.

The effect of selective complement and CD14 inhibition on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and Escherichia coli (E.coli)-induced monocyte tissue factor (TF) surface expression. Fresh human whole blood was incubated for 2 h with LPS (100 ng/ml) (a) or E. coli (1 × 107/ml) (b). The inhibitors and controls were added as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Monocyte tissue factor (TF) surface expression was analysed using flow cytometry, and the results are expressed as the median fluorescence intensity (MFI). The values are given as the means with 95% confidence interval (CI) from separate experiments with different blood donors (n = 6). #P < 0·05: comparison between phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone and LPS (a) or E. coli (b). *P < 0·05: comparison between with LPS (a) or E. coli (b) and the inhibitors/controls. §P < 0.05: selective comparison between single and combined inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD14. (c) Histogram of TF surface expression on monocytes in one of six donors analysed using flow cytometry after 2 h incubation with PBS (light grey), E. coli (medium grey), E. coli plus compstatin and anti-CD14F(ab′)2 combined (dark grey).

Incubation with E. coli significantly (P < 0·05) increased the TF surface expression by 3·7-fold, from 309 MFI in the PBS control to 1152 MFI after 2 h of incubation (Fig. 3b). Consistent with previous findings 13, compstatin and anti-CD14 combined were most efficient, significantly (P < 0·05) reducing E. coli-induced TF surface expression to 157 MFI. Compstatin alone significantly (P < 0·05) reduced TF surface expression to 495 MFI, and anti-CD14 significantly (P < 0·05) reduced TF expression to 614 MFI. An example of the histogram from the flow cytometric analysis of the TF surface expression is shown in Fig. 3.

The effect of selective and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on LPS- and E. coli-induced TF functional activity in plasma microparticles

Incubation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 2 h significantly (P < 0·05) increased the TF functional activity in plasma microparticles by 6·5-fold, from 0·06 to 0·39 mU/ml (Fig. 4a). The combined inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD14 significantly (P < 0·05) reduced LPS-induced TF functional activity to 0·02 mU/ml compared to compstatin alone.

Figure 4.

The effect of selective complement and CD14 inhibition on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and Escherichia coli (E.coli)-induced tissue factor (TF) functional activity in plasma microparticles. Fresh human whole blood was incubated for 2 h with LPS (100 ng/ml) (a) or E. coli (1 × 107/ml) (b). The inhibitors and controls that were added are described in the legend for Fig. 1. Plasma microparticles were isolated using high-speed centrifugation, and TF functional activity was analysed using a amidolytic assay and expressed as mU/ml. The values are given as the means with 95% confidence interval (CI) from separate experiments with different blood donors (n = 6). #P < 0·05: comparison between phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone and LPS (a) or E. coli (b). *P < 0·05: comparison between LPS (a) or E. coli (b) and the inhibitors/controls. §P < 0·05: selective comparison between single and combined inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD14.

Incubation with E. coli (1 × 107/ml) for 2 h significantly (P < 0·05) increased TF functional activity in plasma microparticles by 6·2-fold, from 0·13 to 0·81 mU/ml (Fig. 4b). Consistent with previous findings 13, combined compstatin and anti-CD14 significantly (P < 0·05) reduced the functional activity to 0·06 mU/ml. The combined inhibition was significantly (P < 0·05) more efficient than inhibition with anti-CD14 and compstatin alone.

The effect of an anti-TF blocking antibody on LPS-and E. coli-induced coagulation

Incubation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 2 h increased PTF1·2 levels by 23-fold, from 0·61 in the PBS control to 13·8 nmol/l (Fig. 5a). The anti-TF blocking mAb significantly (P < 0·05) reduced PTF1·2 levels to 3·1 nmol/l, whereas the control mAb did not reduce PTF1·2 levels.

Figure 5.

The effect of an anti- tissue factor (TF) blocking antibody on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and Escherichia coli (E.coli)-induced coagulation, as assessed by measuring prothrombin fragment F 1+2 (PTF1.2) levels. LPS (100 ng/ml) (a) or E. coli (1 × 107/ml) (b) were added to human whole blood and incubated for 2 h. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), anti-TF (aTF, 5 µg/ml) or an isotype control antibody (Ctrl., 5 µg/ml) were added before stimulation with LPS or E. coli. Plasma PTF1.2 levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and expressed as nmol/l. The values are given as the means with 95% CI from separate experiments with different blood donors (n = 7). #P < 0·05: comparison between PBS alone and LPS (a) or E. coli (b). *P < 0·05: comparison between LPS (a) or E. coli (b) and anti-TF or the isotype control antibody.

Incubation with E. coli (1 × 107/ml) increased PTF1·2 levels by 23-fold, from 0·83 nmol/l in the PBS control to 18·7 nmol/l (Fig. 5b). Again, the anti-TF blocking mAb reduced PTF1·2 levels significantly (P < 0·05) to 5·2 nmol/l.

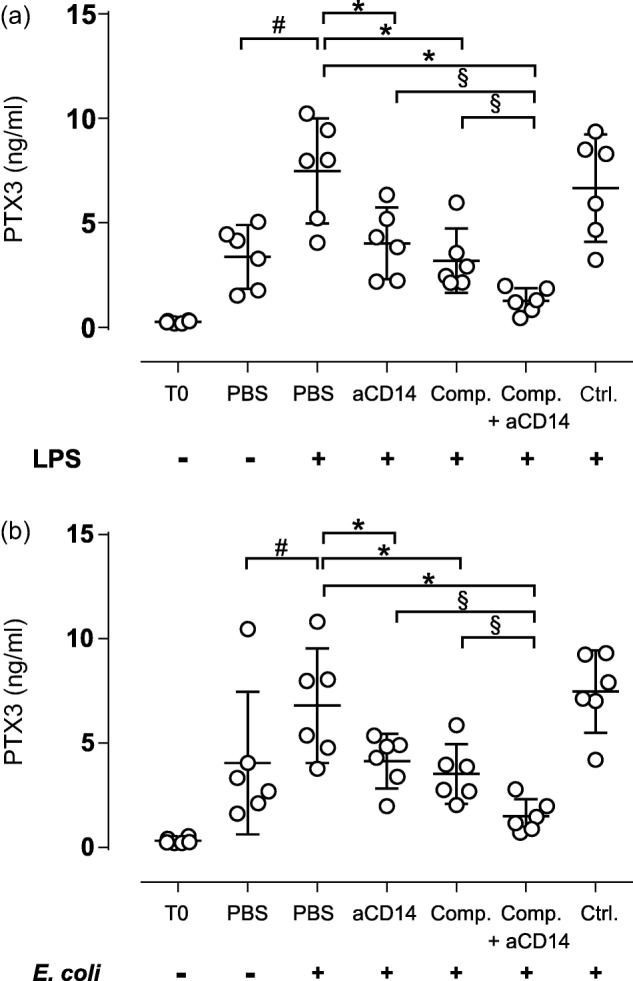

The effect of selective and combined complement and CD14 inhibition on LPS- and E. coli-induced PTX3 levels

Next, we examined the effect of compstatin and anti-CD14 on LPS- and E. coli-induced PTX3 release (Fig. 6). Incubation with LPS for 2 h increased PTX3 levels by 2·2-fold, from 3·4 in the PBS control to 7·5 ng/ml (Fig. 6a). Anti-CD14 and compstatin alone reduced LPS-induced PTX3 release significantly (P < 0·05) to 4·0 and 3·2 ng/ml, respectively. Combined anti-CD14 and compstatin reduced LPS-induced PTX3 levels significantly (P < 0·05) to 1·3 ng/ml. The combined inhibition was significantly (P < 0·05) more efficient than the inhibition with anti-CD14 and compstatin alone.

Figure 6.

The effect of selective complement and CD14 inhibition on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and Escherichia coli (E.coli)-induced long pentraxin 3 (PTX3) release. Fresh human whole blood was incubated for 2 h with LPS (100 ng/ml) (a) or E. coli (1 × 107/ml) (b). The inhibitor and control concentrations are indicated in the legend of Fig. 1. Plasma PTX3 levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and expressed as ng/ml. The values are given as the means with 95% confidence interval (CI) from separate experiments with different blood donors (n = 6). #P < 0·05: comparison between phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone and LPS (a) or E. coli (b). *P < 0·05: comparison between LPS (a) or E. coli (b) and the inhibitors/controls. §P < 0·05: selective comparison between single and combined inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD14.

Incubation with E. coli (1 × 107/ml) for 2 h enhanced PTX3 levels significantly (P < 0·05) by 1·7-fold, from 4·0 ng/ml in the PBS control to 6·8 ng/ml (Fig. 6b). Anti-CD14 and compstatin alone reduced PTX3 levels significantly (P < 0·05) to 4·1 and 3·5 ng/ml, respectively. The combined inhibition with compstatin and anti-CD14 reduced PTX3 levels significantly (P < 0·05) to 1·5 ng/ml. The combined inhibition was significantly (P < 0·05) more efficient than the inhibition with anti-CD14 and compstatin alone.

Discussion

In this study we show for the first time, to our knowledge, that combined complement and CD14 inhibition inhibited LPS- and E. coli-induced coagulation efficiently, as assessed by measuring PTF1·2 levels in human whole blood. Combined complement and CD14 inhibition efficiently inhibited LPS-induced TF mRNA levels, monocyte TF surface expression and TF functional activity in plasma microparticles. Consistent with previous data using other E. coli concentrations 13, we confirmed that this was also the case for E. coli-induced TF induction. Most importantly, we documented that a blocking mAb against TF nearly abolished both the LPS and E. coli-induced increase in PTF1·2 level, indicating that prothrombin activation is TF-dependent and that the upstream activation was largely complement- and CD14-mediated. These findings might have important implications for the treatment of DIC in sepsis.

The significant effect of the C3 convertase inhibitor compstatin on LPS- and E. coli-induced coagulation indicates a key role for complement activation in coagulation. It is well known that E. coli bacteria activate both the classical and alternative complement pathways 12. E. coli bacteria phagocytosis can be reduced significantly by complement inhibition at the C3 level 12. Reduced phagocytosis of E. coli due to compstatin most probably reduces immune stimulation and cytokine release in whole blood monocytes and other phagocytes 11,16. Additionally, reduced E. coli-induced C5a formation and cytokine release by compstatin could explain why complement inhibition was more effective than selective CD14 inhibition at reducing E. coli-induced coagulation 21. Our results further indicate that complement activation is involved early on in TF-mediated LPS- and E. coli-induced coagulation. Although previous studies on E. coli-induced complement activation detected TCC after 10 min of incubation 12, monocyte TF surface expression does not appear for 2–3 h 13. Therefore, we speculate that the initial complement activation up-regulates TF mRNA, followed by enhanced monocyte TF surface expression and subsequent coagulation. Although LPS added to whole blood only modestly activates complement 11, complement inhibition with compstatin reduced LPS-induced coagulation efficiently. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that blocking even a low degree of LPS-induced complement activation is sufficient to attenuate TF expression.

CD14 is especially important for LPS-induced inflammation 22. Therefore, the impressive effect of anti-CD14 on LPS-induced coagulation and TF expression was expected. The CD14 antibody hinders LPS–LBP complex binding to and activation of the TLR-4/CD14/MD2 complex 23. However, anti-CD14 had only a minor effect on E. coli-induced coagulation. Hellerud et al. demonstrated that by increasing the concentration of an LPS-deficient Neisseria meningitidis strain 10-fold, the inflammatory response was the same as for the wild-type, LPS-containing bacteria. Clearly, molecules on Gram-negative bacteria other than LPS are able to activate the inflammatory responses and coagulation 24.

LPS- and E. coli-induced PTX3 release was reduced significantly by both complement- and CD14 inhibition alone and in combination. PTX3 has a number of functions in innate immunity in general, and in complement in particular 25. On one hand, high PTX3 levels during sepsis are associated with mortality 26. PTX3 levels are increased by certain cytokines, including TNF and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as LPS and microorganisms 27. Interestingly, PTX3 also enhances TF surface expression 28, binds to antigens or other activating surfaces and activates both the classical and lectin complement pathways 27. On the other hand, PTX3 seems to be protective, indicated by LPS-induced inflammation in PTX3 knock-out mice 29, as a previous study indicated that the interaction between PTX3 and P-selectin might reduce leucocyte recruitment to the inflammatory site, leading to reduced local inflammation 30, and that between PTX3 and complement factor H may inhibit the amplification loop to the alternative pathway 27. Therefore, PTX3 may both enhance and reduce complement activation. Because PTX3 release in this study was partly complement-dependent, we speculate that a loop with a reciprocal effect exists between complement and PTX3. Notably, CD14 inhibition also attenuated PTX3 release induced both by LPS and E. coli. Finally, the effective reduction of PTX3 release by combined complement and CD14 inhibition indicates a synergistic effect of complement and CD14 (and TLRs) on PTX3 release, which might have implications for the dual therapeutic regimen.

A limitation of the whole blood model is that lepirudin prevents thrombin activation and effects of thrombin can therefore not be evaluated. Thrombin is involved in both the coagulation and complement cascades and participates in the amplification aspect of coagulation. Huber-Lang et al. demonstrated that thrombin may cleave C5 directly 31. Compstatin inhibits at the C3-level and would therefore not interfere with a direct thrombin-mediated C5 activation. However, whole blood experiments cannot be performed without an anti-coagulant. Lepirudin has the advantage of not affecting complement activation; citrate, heparin and EDTA cannot be used because these anti-coagulants affect complement activation 12. Thus, although the model does not include endothelial cells, it is the closest possible to physiological conditions at present. The fact that prothrombin was activated implies a subsequent activation of thrombin, and therefore our data support a strong indication that thrombin would have been activated and lead to a fulminant coagulation in the absence of lepirudin.

In summary, combined complement and CD14 inhibition was most effective for all of the parameters studied in this model of LPS- and E.coli-induced coagulation in human whole blood. The results indicate a very early and pivotal co-operation between complement and CD14/TLRs in immunothrombosis. Combined inhibition of complement and CD14 is suggested to prevent TF up-regulation and the subsequent prothrombin activation and coagulation leading to DIC in sepsis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from The Northern Norway Regional Health Authority and the Somatic research fund at Nordland Hospital, Bodø, Norway, The Research Council of Norway, The Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Disease, The Southern and Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, Odd Fellow Foundation and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. 602699 (DIREKT).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Skrupky LP, Kerby PW, Hotchkiss RS. Advances in the management of sepsis and the understanding of key immunologic defects. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:1349–62. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823422e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackman N. The many faces of tissue factor. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl. 1):136–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoleone E, di Santo A, Peri G, et al. The long pentraxin PTX3 up-regulates tissue factor in activated monocytes: another link between inflammation and clotting activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:203–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1003528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Doni A, Bottazzi B. Pentraxins in innate immunity: from C-reactive protein to the long pentraxin PTX3. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann B, Massberg S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:34–45. doi: 10.1038/nri3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr TA, Rao LV, Rapaport SI. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in rabbits induced by administration of endotoxin or tissue factor: effect of anti-tissue factor antibodies and measurement of plasma extrinsic pathway inhibitor activity. Blood. 1990;75:1481–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow JC, Young DW, Golenbock DT, Christ WJ, Gusovsky F. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10689–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, et al. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1777–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohto U, Fukase K, Miyake K, Satow Y. Crystal structures of human MD-2 and its complex with antiendotoxic lipid IVa. Science. 2007;316:1632–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1139111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni I, Granucci F. Role of CD14 in host protection against infections and in metabolism regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:32. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke OL, Christiansen D, Fure H, Fung M, Mollnes TE. The role of complement C3 opsonization, C5a receptor, and CD14 in E. coli-induced up-regulation of granulocyte and monocyte CD11b/CD18 (CR3), phagocytosis, and oxidative burst in human whole blood. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1404–13. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollnes TE, Brekke OL, Fung M, et al. Essential role of the C5a receptor in E. coli-induced oxidative burst and phagocytosis revealed by a novel lepirudin-based human whole blood model of inflammation. Blood. 2002;100:1869–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke OL, Waage C, Christiansen D, et al. The effects of selective complement and CD14 inhibition on the E. coli-induced tissue factor mRNA upregulation, monocyte tissue factor expression, and tissue factor functional activity in human whole blood. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;735:123–36. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4118-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollnes TE, Christiansen D, Brekke OL, Espevik T. Hypothesis: combined inhibition of complement and CD14 as treatment regimen to attenuate the inflammatory response. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;632:253–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt-Due A, Pischke SE, Brekke OL, et al. Bride and groom in systemic inflammation – the bells ring for complement and Toll in cooperation. Immunobiology. 2012;217:1047–56. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke OL, Christiansen D, Fure H, et al. Combined inhibition of complement and CD14 abolish E. coli-induced cytokine-, chemokine- and growth factor-synthesis in human whole blood. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:3804–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappegard KT, Riesenfeld J, Brekke OL, Bergseth G, Lambris JD, Mollnes TE. Differential effect of heparin coating and complement inhibition on artificial surface-induced eicosanoid production. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:917–23. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikis D, Assa-Munt N, Sahu A, Lambris JD. Solution structure of Compstatin, a potent complement inhibitor. Protein Sci. 1998;7:619–27. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollnes TE, Redl H, Hogasen K, et al. Complement activation in septic baboons detected by neoepitope-specific assays for C3b/iC3b/C3c, C5a and the terminal C5b-9 complement complex (TCC) Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstad CS, Lia K, Rekdal O, Olsen JO, Osterud B. A novel biological effect of platelet factor 4 (PF4): enhancement of LPS-induced tissue factor activity in monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:575–81. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.5.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappegard KT, Christiansen D, Pharo A, et al. Human genetic deficiencies reveal the roles of complement in the inflammatory network: lessons from nature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15861–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903613106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbon A, Dekkers PE, Ten HT, et al. IC14, an anti-CD14 antibody, inhibits endotoxin-mediated symptoms and inflammatory responses in humans. J Immunol. 2001;166:3599–605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SL, June CH, DeFranco AL. Lipopolysaccharide-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation in human macrophages is mediated by CD14. J Immunol. 1993;151:3829–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerud BC, Stenvik J, Espevik T, Lambris JD, Mollnes TE, Brandtzaeg P. Stages of meningococcal sepsis simulated in vitro, with emphasis on complement and Toll-like receptor activation. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4183–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00195-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon S, Bonavita E, Gentile S, et al. The long pentraxin PTX3 as a key component of humoral innate immunity and a candidate diagnostic for inflammatory diseases. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2014;165:165–78. doi: 10.1159/000368778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen R, Hurme M, Aittoniemi J, et al. High plasma level of long pentraxin 3 (PTX3) is associated with fatal disease in bacteremic patients: a prospective cohort study. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e17653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inforzato A, Doni A, Barajon I, et al. PTX3 as a paradigm for the interaction of pentraxins with the complement system. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoleone E, di Santo A, Bastone A, et al. Long pentraxin PTX3 upregulates tissue factor expression in human endothelial cells: a novel link between vascular inflammation and clotting activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:782–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000012282.39306.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Haitsma JJ, Zhang Y, et al. Long pentraxin PTX3 deficiency worsens LPS-induced acute lung injury. Intens Care Med. 2011;37:334–42. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deban L, Russo RC, Sironi M, et al. Regulation of leukocyte recruitment by the long pentraxin PTX3. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:328–34. doi: 10.1038/ni.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, et al. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12:682–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]