Abstract

Background

The key metabolic enzyme lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) is overexpressed in many cancers, and several preclinical studies have shown encouraging results of targeted inhibition. However, the mechanistic importance of LDHA in melanoma is largely unknown and hitherto unexplored in brain metastasis.

Methods

We investigated the spatial, temporal, and functional features of LDHA expression in melanoma brain metastasis across multiple in vitro assays, in a robust and predictive animal model employing MRI and PET imaging, and in a unique cohort of 80 operated patients. We further assessed the genomic and proteomic landscapes of LDHA in different cancers, particularly melanomas.

Results

LDHA expression was especially strong in early and small brain metastases in vivo and related to intratumoral hypoxia in late and large brain metastases in vivo and in patients. However, LDHA expression in human brain metastases was not associated with the number of tumors, BRAFV600E status, or survival. Moreover, LDHA depletion by small hairpin RNA interference did not affect cell proliferation or 3D tumorsphere growth in vitro or brain metastasis formation or survival in vivo. Integrated analyses of the genomic and proteomic landscapes of LDHA indicated that LDHA is present but not imperative for tumor progression within the CNS, or predictive of survival in melanoma patients.

Conclusions

In a large patient cohort and in a robust animal model, we show that although LDHA expression varies biphasically during melanoma brain metastasis formation, tumor progression and survival seem to be functionally independent of LDHA.

Keywords: brain metastasis, lactate dehydrogenase A, LDHA, melanoma, metabolism

The incidence of melanoma is increasing, and the number of life years lost is higher than that for most other solid tumors.1 Despite major therapeutic advances in recent years, most patients with metastatic melanoma ultimately succumb to their disease.2 Importantly, melanoma patients carry a high risk of developing brain metastases for which there are few effective treatment options.3

The Warburg effect is a common feature of cancer cells where they switch to aerobic glycolysis instead of oxidative phosphorylation.4,5 This results in increased lactate production even at normal oxygen concentrations. It has been suggested that this capacity renders the cancer cells metabolically autonomous and provides them with a higher invasive and metastatic potential.6 However, it is still unclear whether the Warburg effect is a consequence of or a contributor to cancer.6

Therapeutic inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) has been pointed to as an attractive treatment strategy for many cancers.4,7,8 LDHA catalyzes the interconversion of pyruvate to lactate, coupled with the oxidation of NADH to NAD+. Many cancers display elevated levels of LDHA, and high LDHA expression has been associated with a poor prognosis in several malignancies.9–12 Moreover, several preclinical studies have shown beneficial effects of LDHA inhibition in various cancers,12–21 but not in melanoma or brain metastases. Unfortunately, most currently available LDHA inhibitors are hampered by low potency and systemic toxicity that limit their clinical application.8 Nonetheless, inhibition of LDHA is believed to be safe; its expression is largely relegated to skeletal muscle, and hereditary LDHA deficiency only causes exertional muscle cramps and myoglobinuria.22,23 Significant efforts are therefore focused at developing more specific and effective compounds that target LDHA.7,24

The rewired metabolic network in cancers has emerged as a promising venue for the development of targeted therapeutics.25 Still, metabolomics involves complex processes with multiple compensatory routes, and systemic rearrangements are highly heterogeneous across and within various cancers.26 Hence, the efficacy of anticancer agents will probably differ among cancer types and metabolic phenotypes.7 Furthermore, given the profound interplay between tumor and host microenvironment, it is reasonable to believe that the organ site has important ramifications for tumor growth and metastasis formation, particularly in the central nervous system.27–29

The mechanistic importance of LDHA in metastatic melanoma, and in particular brain metastasis, is to our knowledge not known. We therefore explored the significance of LDHA in melanoma brain metastasis in a reproducible and predictive animal model,30 in a large cohort of patients with brain metastases from melanoma, across several in vitro assays, and within its contemporary genomic and proteomic landscapes. In brief, our findings question the promise of LDHA as a potential therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma, especially in brain metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Lactate Dehydrogenase A Knockdown

The BRAFV600E-positive H1 cell line was generated from a human melanoma brain metastasis, authenticated within the last 6 months using short tandem repeat profiling, and maintained as reported previously.30 The mutation status of LDHA in the H1 cell line was determined by next-generation RNA sequencing; LDHA was highly expressed (ie, 99.45 fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped), and variant analysis did not reveal any mutations within the coding region of LDHA (see Supplementary material). The expression of LDHA was knocked down by using lentivirus-transduced small hairpin (sh)RNA. Cellular LDHA mRNA levels were quantified by real-time quantitative PCR (see Supplementary material). The cell lines were named H1_WT (naïve H1), H1_LDHA_KD (H1 LDHA knockdown), and H1_shCtr (H1 empty vector control). To validate the efficacy of the shRNA construct, we transfected 2 other cell lines (MELMET5 from a human melanoma lymph node metastasis and PC14-PE6_Br2 from a human lung adenocarcinoma serially passaged in mouse brains).

Western Blotting and Immunohistochemistry

Protein expression levels of LDHA, LDHB (lactate dehydrogenase B), hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) in cultured cells and tumor xenografts were determined by western blot analysis. Immunohistochemical analyses of Ki67 and LDHA expression were carried out on mouse brains, adrenals, ovaries, and femurs (see Supplementary material).

Metabolic Flux Analysis

To show the effect of LDHA silencing on cellular metabolism, we determined the extracellular acidification rate and the oxygen consumption rate of cells by performing a glycolysis stress test and mito stress test using the Seahorse XF-96 Extracellular Flux analyzer (see Supplementary material).

Proliferation and Tumorsphere Assays

Standardized monolayer proliferation assays and 3D tumorsphere growth assays were carried out as described in the Supplementary material.

In vivo Cell Injections and Quantification of Melanoma Cell Load in the Brain

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Bergen and by the Norwegian Animal Research Authority and carried out using 6- to 8-week-old female nonobese diabetic severe combined immunodeficient mice bred and maintained in animal facilities certified by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Anesthesia was induced with 3% and maintained with 1.5% isoflurane in oxygen. Mice were monitored daily and sacrificed when significant morbidity was observed.

Cells (5 × 105 per 0.1 mL phosphate buffered saline) were labeled with poly-l-lysine coated maghemite nanoparticles and injected intracardially as reported previously.30 Intracardiac injections were ultrasound guided using a custom-made needle holder fitted to a 40-MHz MS-550D MicroScan transducer (Vevo 2100 system, VisualSonics).

To ensure homogeneous group comparisons, we assessed melanoma cell load in the brain 24 h after injection by automated MRI-based quantification of nanoparticle-labeled cells in the brain, including a cell line–specific training set for neural network analysis as described previously (see Supplementary material).30

Only mice with comparable tumor cell exposure in their brains (T2*-weighted) and without focal brain lesions (T2-weighted) on the 24-h MRI were routed to further follow-up (H1_WT, n = 5; H1_LDHA_KD, n = 13; and H1_shCtr, n = 8). Nine mice with inadequate brain cell load and/or signs of focal lesions were euthanized to ensure optimal model predictivity (H1_WT, n = 3; H1_LDHA_KD, n = 2; and H1_shCtr, n = 4).

For the temporal investigation of LDHA expression in brain metastasis formation, we injected 12 mice with H1_WT cells and euthanized 3 mice every week for 4 weeks. These mice did not undergo any imaging.

In vivo MRI and PET Imaging of Brain Metastases

MRI was carried out 6 weeks after injection to evaluate brain metastatic burden (T2-weighted and pre-/postcontrast T1-weighted; see Supplementary material). Tumor number and volume (4/3 × π × r3) were assessed using OsiriX 5.8.1 32-bit (Pixmeo).

In parallel with the 6-week MRI, we carried out whole-body F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET on 3 healthy mice (background controls) and 3 random mice from the H1_WT and H1_LDHA_KD groups. We also acquired 3′-deoxy-3′[(18)F]-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT) PET images of 2 healthy mice, 2 H1_WT mice, and 2 H1_LDHA_KD mice (see Supplementary material). Maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) and cerebral tumor-to-brain ratios (SUVmax tumor/SUVmax normal brain) were calculated (see Supplementary material).

Patient Cohort With Melanoma Brain Metastases

This study, and the collection of human melanoma brain metastasis tumor samples and clinical data, was approved by the local ethical committee at Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen and Tübingen University Hospital (approvals 411/2014BO2 and 408/2013BO2) and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Eighty patients surgically treated for brain metastases were included after written informed consent was obtained. Brain MRI data were analyzed for metastasis size (diameter) and number (in cases of >10 metastases in one patient, the number of metastases was set to 10 for statistical analysis). Patient age at surgery and overall survival after surgery were registered. Tissue microarrays (TMAs) of brain metastases were constructed for LDHA, HIF1α, CD31, and BRAFV600E immunohistochemistry (see Supplementary material). Two experienced neuropathologists (P.N.H. and M.M.) analyzed LDHA expression in human TMAs using a semiquantitative score reflecting staining intensity and frequency as described previously31 (and explained in the Supplementary material).

Genomic and Proteomic Landscapes of LDHA and Association With Survival

In independent analyses, we queried the Human Protein Atlas (www.proteinatlas.org) for LDHA alterations at the protein level in normal and cancerous tissues, and the cBioPortal (www.cbioportal.org) for LDHA alterations at the genomic level across 69 available cancer studies and, in particular, within The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provisional dataset of 375 melanoma cases. We also searched the PROGgene database (watson.compbio.iupui.edu/chirayu/proggene/database) for LDHA gene expression levels and associated overall survival in a TCGA melanoma series of 163 patients, and associated brain metastasis–free survival in the Gene Expression Omnibus dataset GSE2603 of 82 breast cancer patients (the only available dataset with this survival measure).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 21 for Mac (IBM) and JMP 8.0.1 (SAS). Data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variances. The statistical tests used are specified in the Results section. Values are presented as means ± SEM or medians with interquartile range (IQR) unless otherwise specified. A 2-tailed P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

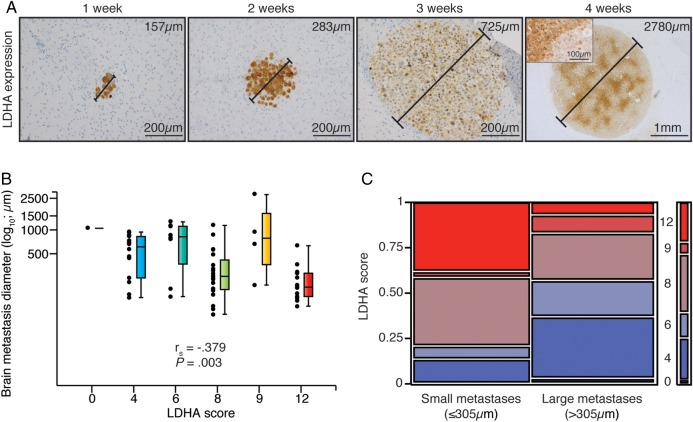

Biphasic Pattern of LDHA Expression in Mouse Melanoma Brain Metastases

To assess the temporal significance of LDHA expression on metastasis formation in vivo, we used a highly standardized brain metastasis model.30 Intriguingly, we found the highest LDHA expression levels in small metastases during the first 2 weeks of brain metastasis formation, and all tumor cells displayed strong LDHA positivity (Fig. 1A). Expression levels thereafter declined as the tumors grew larger, and later increased again with a regionally distinct pattern in large, macroscopic tumors. Accordingly, there was a significant correlation between LDHA score and brain metastasis size (Fig. 1B), as well as a significant difference in LDHA scores between small (≤305 μm) and large (>305 μm) brain metastases (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

LDHA expression levels of melanoma brain metastases in mice displayed a biphasic pattern over time. (A) LDHA immunohistochemistry of brain metastases of increasing size (diameters provided) over 4 wk post intracardiac injection (n = 3 per wk). Inset displays representative staining pattern within the largest metastasis. (B) LDHA score vs brain metastasis size (n = 59; Spearman correlation). No metastases got an LDHA score 1–3. (C) LDHA scores of small (≤305 μm; n = 30) vs large (>305 μm; n = 29) brain metastases (median split; Pearson chi-square test, P = .038).

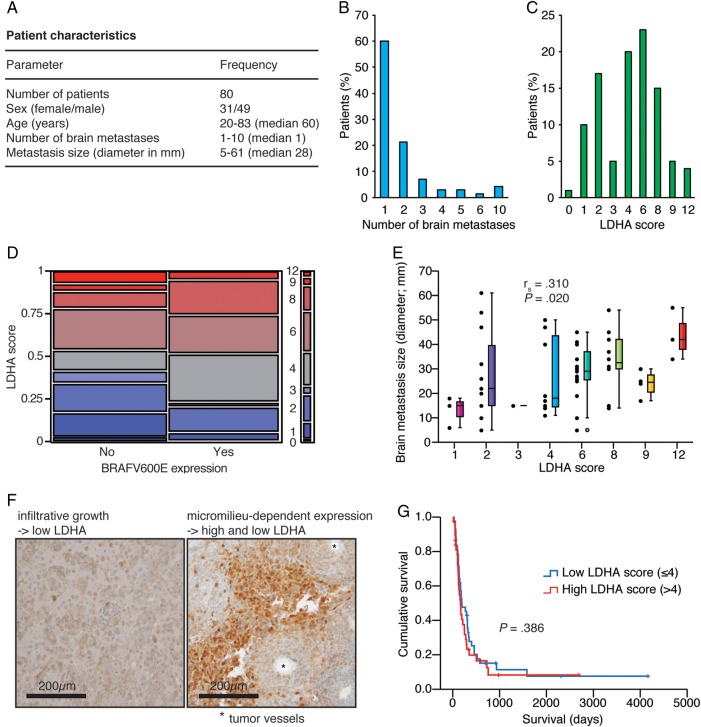

LDHA Expression in Human Brain Metastases Was Not Predictive of Survival but Associated With Tumor Size

To assess the clinical importance of LDHA expression, we studied a large cohort of patients with melanoma brain metastases (Fig. 2A). Notably, 48.75% of the tumors (n = 39 patients) had the BRAFV600E mutation. Twenty-eight patients had more than one brain metastasis, including 3 patients with ≥10 brain metastases (Fig. 2B). The median LDHA score was 4 (Fig. 2C). Importantly, there was no association between LDHA score and BRAFV600E expression status (Fig. 2D). Similarly, we did not observe an association between LDHA score and patient age, or between LDHA score and number of brain metastases (Pearson chi-square test, P = .376 and P = .643, respectively; data not shown). However, we observed a significant association between LDHA score and brain metastasis size, with higher LDHA scores in larger tumors (Fig. 2E); brain metastasis size was available for only 56 patients. Correspondingly, histological sections showed a clear association of LDHA expression with perinecrotic areas in large tumors, whereas perivascular cells showed almost no LDHA expression (Fig. 2F). As expected, co-optive, more diffusely infiltrating tumor cells showed low LDHA expression. Lastly, survival distributions were equal between patients with high versus low LDHA scores (Fig. 2G).

Fig. 2.

LDHA expression levels of human melanoma brain metastases was not predictive of tumor burden or survival but increased with tumor size. (A) Cohort characteristics. (B) Number of brain metastases. (C) LDHA scores. (D) BRAFV600E expression status vs LDHA score (Pearson chi-square test, P = .221). (E) LDHA score vs brain metastasis size (n = 56; Spearman correlation). (F) LDHA immunohistochemistry of diffusely infiltrating tumor cells (left) and micromilieu-dependent expression in the tumor core (right). (G) Kaplan–Meier survival plot of low vs high LDHA score (median split; Mantel–Cox log-rank test). Five patients in the low group and 7 patients in the high group were still alive or lost to follow-up.

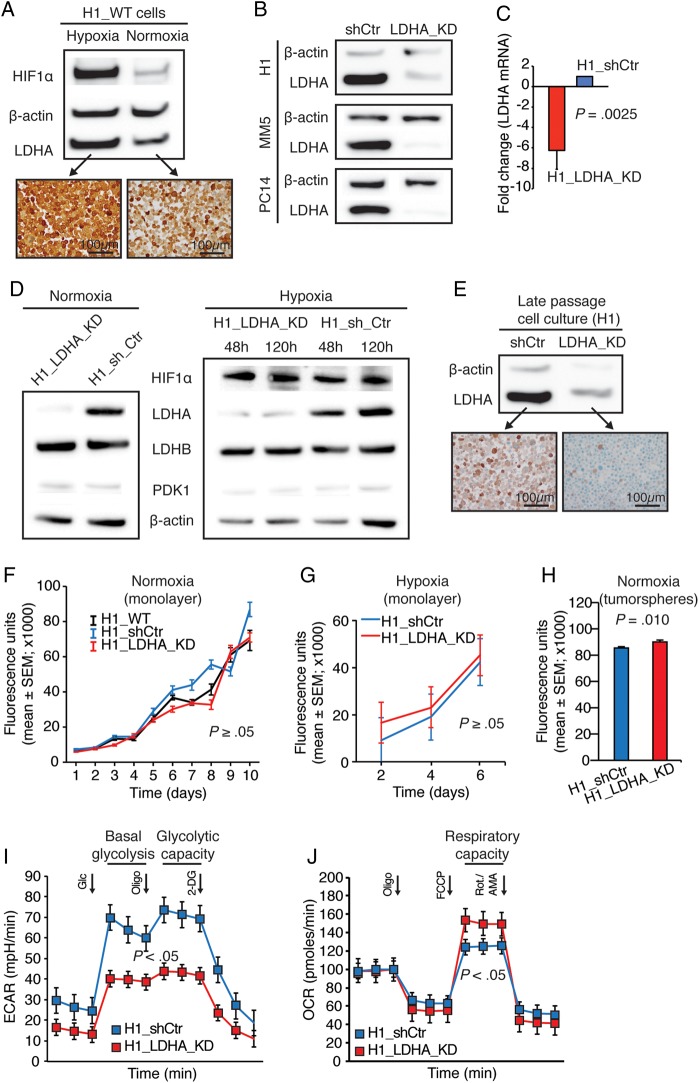

LDHA Knockdown Was Effective and Stable In vitro

To functionally evaluate the potential implications of our preclinical findings (high LDHA expression in microscopic tumors) in contrast to our clinical findings (no clinical impact of LDHA expression in macroscopic tumors), we constructed and validated a stable LDHA knockdown cell line (H1_LDHA_KD). Notably, and in accordance with the Warburg hypothesis,5 H1_WT cells displayed high LDHA expression in hypoxia (Fig. 3A). Transfection efficacy was validated in 3 different metastasis cell lines (Fig. 3B). Quantification of LDHA mRNA levels in transduced H1 cells showed more than a 6-fold reduction (Fig. 3C). We confirmed effective and stable LDHA knockdown at the protein level under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3D) and in long-term cell culture (Fig. 3E). LDHB or PDK1 expression was not affected by LDHA knockdown or by hypoxia, whereas HIF1α expression was induced upon hypoxia (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Cellular LDHA knockdown was effective and stable but did not affect cellular proliferation or tumorsphere growth. (A) Western blots of H1_WT cells in hypoxia and normoxia (48 h) with corresponding LDHA immunocytochemistry. (B) Western blots of control (sh_Ctr) and LDHA knockdown (LDHA_KD) derivatives of H1 and 2 other human metastasis cell lines (MELMET5 [MM5]/melanoma and PC14-PE6_Br2 [PC14]/lung cancer). (C) LDHA mRNA levels in H1 derivatives. Mean knockdown efficiency was 83 ± 3% (n = 3; mean ± SEM; Student t-test). (D) Western blots of H1_LDHA_KD and H1_shCtr cells in normoxia (48 h) and acute (48 h) and chronic (120 h) hypoxia (second passage after green fluorescent protein–positive fluorescence activated cell sorting). (E) Western blot of cells cultured continuously for 2 months with corresponding LDHA immunocytochemistry. (F) Proliferation assay in normoxia (n = 6 per cell line per time point; Kruskal–Wallis test). (G) Proliferation assay in hypoxia (n = 12 per cell line per time point; Student t-test). (H) Tumorsphere assay in normoxia (n = 36 per cell line; Student t-test). (I) Glycolytic stress test in normoxia (n = 3 per cell line per time point; mean ± SEM; Student t-test). (J) Mito stress test in normoxia (n = 2 per cell line per time point; mean ± SEM; Student t-test). (A, D, and G) Hypoxia (1% O2).

LDHA Knockdown Did Not Affect Cell Growth but Induced a Metabolic Shift

We assessed the impact of reduced LDHA levels on cellular proliferation and growth. Monolayer cultures proliferated with similar rates in both normoxia (Fig. 3F) and hypoxia (Fig. 3G). Correspondingly, under normoxic conditions, there was no convincing difference in tumorsphere growth over time albeit mean values were higher for H1_shCtr cells at 10 days (Student t-test, P = .037; data not shown) and for H1_LDHA_KD cells at 17 days (Fig. 3H).

We then investigated the impact of LDHA knockdown on glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration. We performed a glycolytic stress test and observed significantly reduced basal glycolysis and glycolytic capacity in H1_LDHA_KD cells compared with H1_shCtr cells (Fig. 3I). Interestingly, a mito stress test showed significantly increased respiratory capacity in LDHA knockdown cells (Fig. 3J).

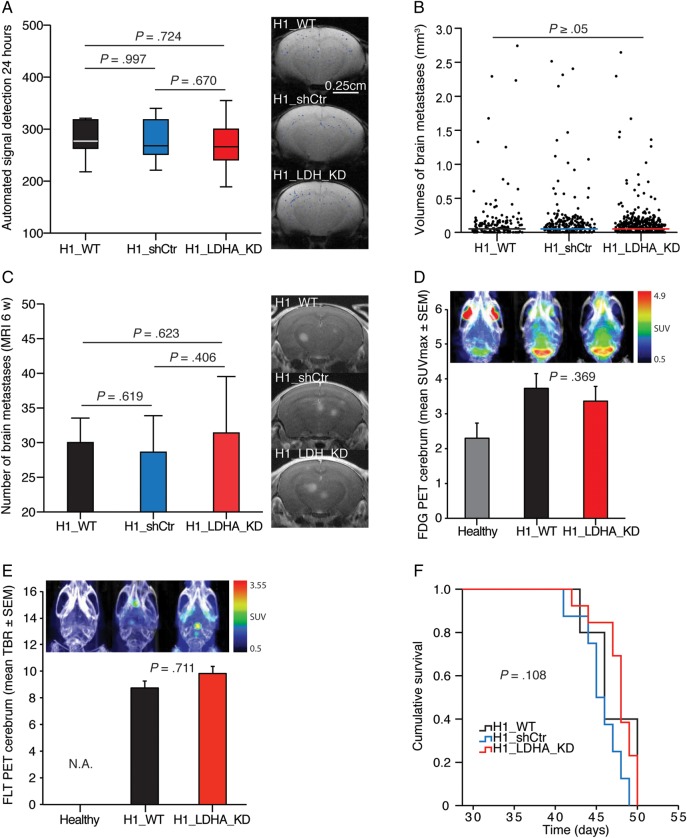

LDHA Knockdown Did Not Affect Brain Metastasis or Survival in Mice

We examined the in vivo consequences of LDHA knockdown using our highly standardized mouse model of brain metastasis.30 Automated quantification of nanoparticle-labeled cells showed no significant differences in baseline tumor cell exposure of mouse brains across study groups (Fig. 4A). The median tumor volumes at 6 weeks were equal, with 0.044 mm3 (IQR = 0.096) for the H1_WT group, 0.045 mm3 (IQR = 0.089) for the H1_shCtr group, and 0.044 mm3 (IQR = 0.061) for the H1_LDHA_KD group (Fig. 4B). There was no difference in the mean number of brain metastases at 6 weeks between groups (Fig. 4C). Neither total cerebral SUVmax values of 18F-FDG PET images (Fig. 4D) nor cerebral tumor-to-brain ratios of 18F-FLT PET images (Fig. 4E) showed any difference in tumor burden between the H1_WT and H1_LDHA_KD groups at 6 weeks. For 18F-FDG PET, there was a significant difference between healthy mice and the H1_WT and H1_LDHA_KD groups (Student t-test, P = .011 and P = .014, respectively). Survival distributions were similar across groups (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

LDHA knockdown did not affect brain metastasis or survival in mice. (A) MRI-based automated quantification of nanoparticle-labeled melanoma cells in mouse brains 24 h post intracardiac injection of 5 × 105 cells (Student t-test). Typical brain MRI T2*-weighted images with an overlay of detected signals. (B) Volumes of individual brain metastases at the 6-wk MRI (Mann–Whitney U test, H1_WT vs H1_shCtr, P = .413; H1_WT vs H1_LDHA_KD, P = .715; H1_LDHA_KD vs H1_shCtr, P = .475). (C) Number of brain metastases at the 6-wk MRI (T1-weighted images with contrast; Student t-test). (D) Maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) on 18F-FDG PET cerebrum at 6 wk (n = 3 per group; Student t-test). Note the high signal intensity in the frontal (Harderian glands) and cerebellar regions in healthy control mice in the combined PET and CT maximum intensity projection (MIP) images. (E) Tumor-to-brain ratio (TBR; SUVmax tumor/SUVmax normal brain) on 18F-FLT PET cerebrum at 6 wk (combined PET and CT MIP images; n = 2 per group; Student t-test). Note the lack of signals in healthy mice, as 18F-FLT does not cross an intact blood–brain barrier (hence, not applicable). (F) Kaplan–Meier survival plot (Mantel–Cox log-rank test). (A–C and F) H1_WT group, n = 5; H1_shCtr group, n = 8; and H1_LDHA_KD group, n = 13.

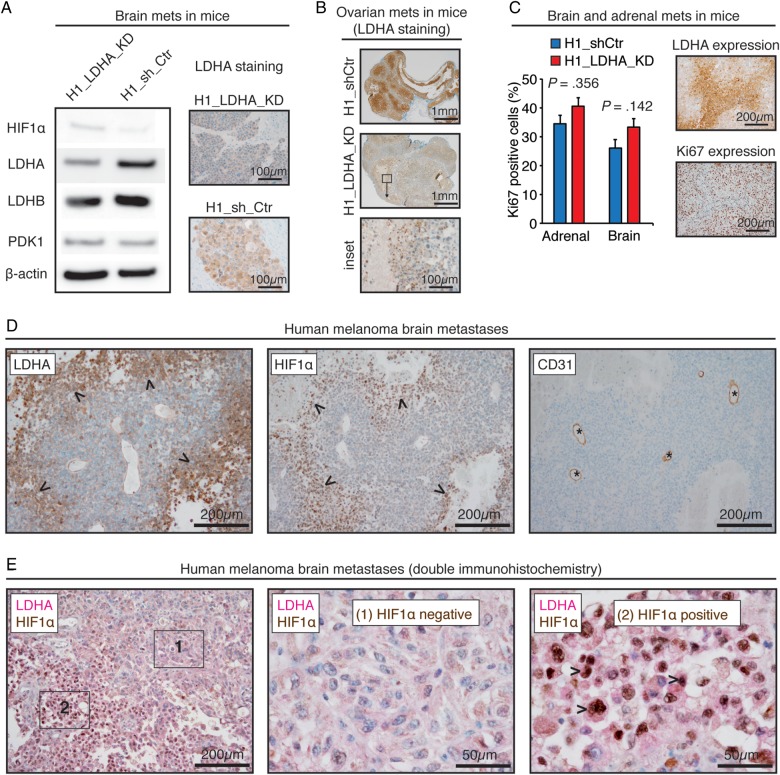

Analyses of Mouse and Human Melanoma Brain Metastases Showed Stable LDHA Knockdown and Hypoxia-Dependent Expression

We next examined the stability of LDHA knockdown, compensatory mechanisms, and specifically the relationship between LDHA and HIF1α expression in tumor xenografts and human TMAs. Mouse brain metastases displayed stable and efficient LDHA knockdown (Fig. 5A). In agreement with our in vitro data, there was no increased LDHB or PDK1 expression in H1_LDHA_KD tumors (Fig. 5A). Moreover, immunohistochemistry of other mouse organs (ovaries, adrenals, femurs) validated a temporal stability of the LDHA knockdown (Fig. 5B) and showed equivalent metastatic patterns between the H1_LDHA_KD and H1_shCtr cell lines. We observed sporadic small colonies of cells still expressing LDHA in some of the H1_LDHA_KD mice. However, a more prevalent observation was that of a perinecrotic regulation with increased LDHA expression in large H1_LDHA_KD tumors of all organs, suggestive of a micromilieu-dependent upregulation (Fig. 5B). Ki67 and LDHA immunostainings of tumor xenografts displayed a mutually exclusive pattern, and Ki67 indices were similar across groups (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

LDHA knockdown was stable in vivo and hypoxia dependent in human melanoma brain metastases. (A) Western blots of brain metastases (mets) in mice with corresponding LDHA immunohistochemistry. (B) LDHA immunohistochemistry of ovarian metastases in mice with inset showing perinecrotic regulation. (C) Ki67-positive cells in brain and adrenal metastases in mice (n = 5; mean ± SEM; Student t-test) with adjacent images showing regionally distinct Ki67 and LDHA patterns. (D) Immunohistochemistry of a human melanoma brain metastasis displaying a spatial overlap of LDHA and HIF1α expression (arrowheads) ∼150 μm from CD31-positive vessels (asterisks). (B) Double immunohistochemistry of a human melanoma brain metastasis and 2 insets showing spatial coexpression of perinuclear LDHA and nuclear HIF1α (arrowheads).

Immunohistochemistry of human melanoma brain metastases showed a spatial association of LDHA and HIF1α expression in perinecrotic regions and in tumor cells far from CD31-positive vessels (Fig. 5D); double immunohistochemistry confirmed the spatial coexpression of LDHA and HIF1α (Fig. 5E).

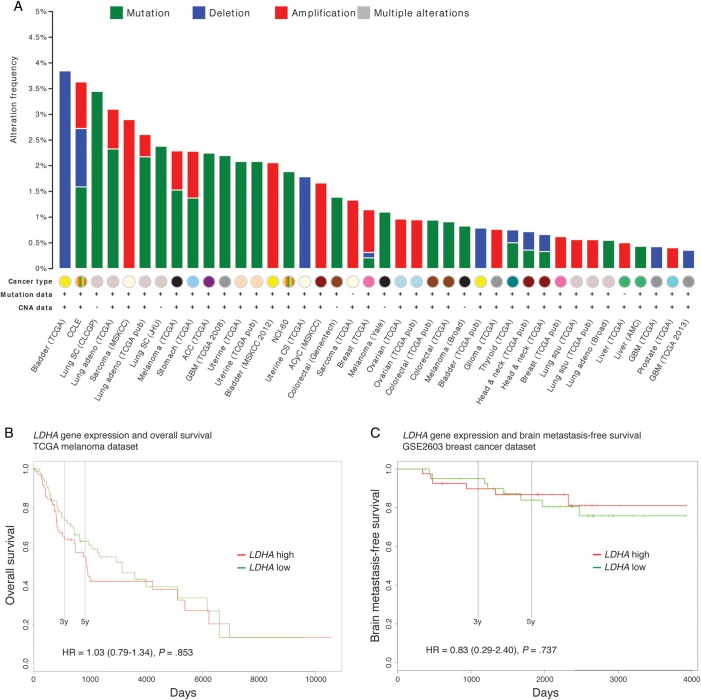

Proteomic and Genomic Landscapes of LDHA and Prognostic Potential

We explored the proteomic and genomic landscapes of LDHA across publicly available and state-of-the-art data series. Indeed, most normal and cancerous tissue samples in the Human Protein Atlas displayed moderate cytoplasmic and nuclear LDHA positivity (data not shown). Moderate degrees of LDHA staining could be seen in 11 of 12 melanoma samples (primary and metastatic; no brain metastases). Interestingly, the most prevalent primary malignant brain tumors—malignant gliomas—were generally weakly stained.

LDHA was genetically altered in 5% of 375 available TCGA melanoma samples, with 2 cases of amplification, 4 cases of mutation, and 13 cases of mRNA upregulation; manual review of the featured pathology reports revealed no altered cases originating from brain metastases (cBioPortal, data not shown). The frequency of LDHA mutations, deletions, or amplifications ranged from 0% to 3.8% across 69 available cancer studies; 19 studies did not report any LDHA alterations (Fig. 5A). LDHA alterations were infrequent in all melanoma series: 0% in the Broad/Dana Farber study of 25 cases,32 0.8% in the Broad study of 121 cases,33 1.1% in the Yale study of 91 cases,34 and 2.3% in TCGA data of 262 cases (Fig. 5A).

Finally, we investigated the prognostic potential of LDHA expression levels using the PROGgene database. We did not find statistically detectable associations with overall survival in TCGA melanoma patients (Fig. 5B) or with brain metastasis–free survival in breast cancer patients (Fig. 5C; GSE2603 was the only available dataset with this survival measure).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the preclinical and clinical relevance of LDHA in melanoma brain metastasis. The temporal trends of LDHA expression in vivo suggested that LDHA was important early in metastasis formation, as well as later when the tumors outgrew their blood supply (Fig. 1). LDHA expression in operated human melanoma brain metastases was similarly micromilieu dependent, but not a predictor of survival (Fig. 2). As LDHA expression levels are difficult to interrogate in microscopic human tumors, we carried out a comprehensive in vitro and in vivo assessment of LDHA interference (Figs. 3 and 4). In brief, LDHA depletion did not affect cell proliferation or growth or brain metastasis or survival in mice. LDHA expression was, however, strongly associated with hypoxia both in vivo and in patients (Figs. 2, 3, and 5). Notably, integrated analyses of independent genomic and proteomic data indicated that LDHA is not a driver of human melanoma brain metastasis or associated with survival (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Genomic alterations of LDHA were infrequent in human melanomas and other cancers, and LDHA expression was not predictive of survival. (A) Histogram showing a summary of LDHA mutations, deletions, and amplifications across 40 of the 69 studies from the cBioPortal (19 studies did not report any alterations). Three melanoma series are featured here: TCGA (provisional), Broad,32 and Yale.33 Abbreviations: CNA (copy number alterations), CCLE (Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia), SC (small cell), adeno (adenocarcinoma), CLCGP (Clinical Lung Cancer Genome Project), MSKCC (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center), JHU (Johns Hopkins University), ACC (adrenocortical carcinoma), GBM (glioblastoma multiforme), NCI-60 (National Cancer Institute panel of 60 cell lines), CS (carcinosarcoma), ACyC (adenoid cystic carcinoma), Squ (squamous cell carcinoma), and AMC (Asan Medical Center). (B) Overall survival between low and high LDHA expression groups in 163 TCGA melanoma patients. (C) Brain metastasis–free survival in 82 breast cancer patients from the GSE2603 dataset. (B and C) Cohorts were divided at median of gene expression. Cox proportional hazard ratios (HR) (with CIs) are provided with log-rank test P-values.

Animal studies have shown that LDHA inhibition, by either RNA interference or pharmacological agents, causes beneficial effects on tumor growth in flank models of different cancers,14–16,18,20,21 as well as on tumor growth in an orthotopic breast cancer model,12,13 on lung metastasis in an orthotopic breast cancer model,12 and on tumor growth and intrahepatic and pulmonary metastasis in an orthotopic model of hepatocellular carcinoma.17 Notably, most in vivo models used to evaluate novel anticancer drugs rely on s.c. flank injections of tumor cell lines and caliper measurements of tumor size. Understandably, results from such models have limited validity for brain metastasis (eg, one major concern being the limitations given by the blood–brain barrier).

Recently, Xie and colleagues19 used genetically engineered mouse models of KRAS and EGFR driven non–small cell lung cancer and showed that inactivation of LDHA led to decreased tumorigenesis and disease regression. Conversely, in a recent study of lymphoma in mice carrying an inactivating germline mutation of LDHA, tumor development was not affected.35 These findings, using advanced animal model systems, show that LDHA dependency is not ubiquitous for human cancers and that tumors can adapt to different metabolic phenotypes. Moreover, to achieve clinical success using LDHA inhibitors, it will be necessary to stratify cancers and patients at a more individual level and develop combinatorial regimens including inhibitors of other metabolic enzymes.

Furthermore, and important in the context of the animal model used herein, the findings of Xie and colleagues and Nilsson and colleagues also testify to the importance of robust and predictive model systems.19,35 We recently presented a tailored brain metastasis model where tumor cell dissemination to the brain is automatically quantified (Fig. 4).30 This model enables unprecedented methodological control—essential to draw reliable conclusions of biological differences and therapeutic efficacy—and features state-of-the-art and complementary imaging platforms (eg, MRI and PET imaging).

Strong LDH-5 expression has been found in thick primary melanomas; LDH-5 is composed of 4 LDHA-encoded M subunits and is the predominant isoenzyme in liver and striated muscle.36 However, and consistent with our findings (Figs. 2, 4, and 6), LDH-5 was not found to be an independent marker of prognosis in primary melanoma by multivariate analysis.36

An elevated serum level of LDH (LDHA and LDHB) in melanoma is predictive of metastatic disease and reduced survival.37,38 The rise in these enzymes is probably caused by melanoma cell death as tumors outgrow their blood supply; increased levels of LDHA within cells are thought to be mediated largely by the transcription factor HIF1α.39,40 This notion is in accordance with our findings of hypoxia-induced HIF1α expression, a micromilieu-dependent LDHA expression in perinecrotic areas, and increased LDHA expression with increasing distance from tumor vessels (Figs. 1–3, Fig. 5). Furthermore, we did not observe any compensatory increase in LDHB or PDK141 expression with LDHA knockdown or hypoxia (Figs. 3 and 5).

Anticancer drug efficacy differs by cancer type and metabolic phenotype,7 and the organ site has an essential influence on tumor growth and metastasis formation, particularly in the central nervous system.27–29 Intriguingly, we observed increased respiratory capacity in LDHA knockdown cells (Fig. 3), and brain metastasis–free survival in breast cancer was independent of LDHA expression (Fig. 6). Evidence from preclinical work with breast cancer has indeed suggested that brain metastatic cells use enhanced mitochondrial respiratory pathways for energy production, possibly reflecting a predisposition or an adaptation to the high-energy demands of the brain microenvironment.27 In fact, it has been shown that the brain microenvironment can induce a complete reprogramming of breast cancer cells in brain metastases whereby tumor cells acquire neuronal expression patterns.28,29 Given these perspectives, and that gliomas seem to be largely independent of LDHA activity (H. Espedal et al, “LDHA in glioblastomas,” unpublished manuscript; Fig. 6; www.proteinatlas.org), it is perhaps not surprising that there was no functional effect of LDHA inhibition in this study. Moreover, it is also reasonable to relate the missing effect of monotargeting within the metabolic network to its complexity, compensatory trajectories, and heterogeneity across and within various cancers.26 Finally, there is a substantial degree of mutational heterogeneity within cancers, and the most heterogeneous of them all is melanoma.42

In this study, we used a low-generation, human melanoma brain metastasis cell line for all in vitro and in vivo experiments. To some extent this limits the generalizability of our results, in particular the in vitro findings. However, robust in vivo data and comprehensive human data fully supported our in vitro findings. Regarding the human data, it is important to be aware that only patients operated on for melanoma brain metastases were included. Patients without diagnoses and patients not eligible for surgery due to multiple or deep-seated tumors or uncontrolled systemic disease were not included. This clearly introduces a bias that is not easy to circumvent, as such tumor material is difficult to obtain and will require a different study design. Nonetheless, both tumor-bearing mice and tumor-bearing humans were symptomatic and hence comparable when sampled for analyses of LDHA expression and tumor burden; and animal and human survival data were fully concordant (Figs. 2, 4, and 6).

In summary, our results from a large patient cohort and a robust animal model show that LDHA expression varies during melanoma brain metastasis formation and, most importantly, indicate that initiation and progression of tumors as well as patient and animal survival seem to be functionally independent of LDHA. In this context, we propose that the Warburg effect, increased LDHA expression levels, and increased serum levels of LDH are more likely consequences of than contributors to this detrimental disease.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was funded by the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (grants 911645 to T.S. and 911558 to F.T.), the Kristian Gerhard Jebsen Foundation, the University of Bergen, the Norwegian Cancer Society, the Norwegian Research Council, and the Luxembourg Institute of Health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anja Torsvik, University of Bergen, Norway, for support with cell authentication; Clifford Tepper, UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, USA, for analysis of LDHA mutation status; Øystein Fodstad, University of Oslo, Norway, for providing the MELMET5 cell line; Frank Winkler, German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany, for providing the PC14-PE6 cell line; Tina Pavlin, University of Bergen, Norway, for help with MRI sequence setup; and Tom Christian Holm Adamsen, Haukeland University Hospital, Norway, for making PET tracers.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.MacKie RM, Hauschild A, Eggermont AM. Epidemiology of invasive cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(suppl. 6):vi1–vi7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggermont AM, Spatz A, Robert C. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2014;383(9919):816–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flanigan JC, Jilaveanu LB, Chiang VL, et al. Advances in therapy for melanoma brain metastases. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(3):264–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123(3191):309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garber K. Energy deregulation: licensing tumors to grow. Science. 2006;312(5777):1158–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doherty JR, Cleveland JL. Targeting lactate metabolism for cancer therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(9):3685–3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miao P, Sheng S, Sun X, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase A in cancer: a promising target for diagnosis and therapy. IUBMB Life. 2013;65(11):904–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase-5 (LDH-5) overexpression in non-small-cell lung cancer tissues is linked to tumour hypoxia, angiogenic factor production and poor prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(5):877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Simopoulos C, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase 5 (LDH5) relates to up-regulated hypoxia inducible factor pathway and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Winter S, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase 5 expression in squamous cell head and neck cancer relates to prognosis following radical or postoperative radiotherapy. Oncology. 2009;77(5):285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizwan A, Serganova I, Khanin R, et al. Relationships between LDH-A, lactate, and metastases in 4T1 breast tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(18):5158–5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fantin VR, St-Pierre J, Leder P. Attenuation of LDH-A expression uncovers a link between glycolysis, mitochondrial physiology, and tumor maintenance. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(6):425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langhammer S, Najjar M, Hess-Stumpp H, et al. LDH-A influences hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1 α) and is critical for growth of HT29 colon carcinoma cells in vivo. Target Oncol. 2011;6(3):155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le A, Cooper CR, Gouw AM, et al. Inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase A induces oxidative stress and inhibits tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(5):2037–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rong Y, Wu W, Ni X, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase A is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer and promotes the growth of pancreatic cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2013;34(3):1523–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheng SL, Liu JJ, Dai YH, et al. Knockdown of lactate dehydrogenase A suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. FEBS J. 2012;279(20):3898–3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie H, Valera VA, Merino MJ, et al. LDH-A inhibition, a therapeutic strategy for treatment of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(3):626–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie H, Hanai J, Ren JG, et al. Targeting lactate dehydrogenase-A inhibits tumorigenesis and tumor progression in mouse models of lung cancer and impacts tumor-initiating cells. Cell Metab. 2014;19(5):795–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao F, Zhao T, Zhong C, et al. LDHA is necessary for the tumorigenicity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2013;34(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Zhang X, Wang X, et al. Inhibition of LDH-A by lentivirus-mediated small interfering RNA suppresses intestinal-type gastric cancer tumorigenicity through the downregulation of Oct4. Cancer Lett. 2012;321(1):45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanno T, Maekawa M. Lactate dehydrogenase M-subunit deficiencies: clinical features, metabolic background, and genetic heterogeneities. Muscle Nerve Suppl. 1995;3:S54–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyajima H, Takahashi Y, Suzuki M, et al. Molecular characterization of gene expression in human lactate dehydrogenase-A deficiency. Neurology. 1993;43(7):1414–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granchi C, Bertini S, Macchia M, et al. Inhibitors of lactate dehydrogenase isoforms and their therapeutic potentials. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(7):672–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chun MG, Shaw RJ. Cancer metabolism in breadth and depth. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(6):505–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu J, Locasale JW, Bielas JH, et al. Heterogeneity of tumor-induced gene expression changes in the human metabolic network. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(6):522–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen EI, Hewel J, Krueger JS, et al. Adaptation of energy metabolism in breast cancer brain metastases. Cancer Res. 2007;67(4):1472–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neman J, Termini J, Wilczynski S, et al. Human breast cancer metastases to the brain display GABAergic properties in the neural niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(3):984–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park ES, Kim SJ, Kim SW, et al. Cross-species hybridization of microarrays for studying tumor transcriptome of brain metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(42):17456–17461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundstrøm T, Daphu I, Wendelbo I, et al. Automated tracking of nanoparticle-labeled melanoma cells improves the predictive power of a brain metastasis model. Cancer Res. 2013;73(8):2445–2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harter PN, Zinke J, Scholz A, et al. Netrin-1 expression is an independent prognostic factor for poor patient survival in brain metastases. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berger MF, Hodis E, Heffernan TP, et al. Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. Nature. 2012;485(7399):502–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150(2):251–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krauthammer M, Kong Y, Ha BH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic RAC1 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilsson LM, Forshell TZ, Rimpi S, et al. Mouse genetics suggests cell-context dependency for Myc-regulated metabolic enzymes during tumorigenesis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhuang L, Scolyer RA, Murali R, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase 5 expression in melanoma increases with disease progression and is associated with expression of Bcl-XL and Mcl-1, but not Bcl-2 proteins. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weide B, Soyer HP, Richter S, et al. Serum S100B, lactate dehydrogenase and brain metastasis are prognostic factors in patients with distant melanoma metastasis and systemic therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e81624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agarwala SS, Keilholz U, Gilles E, et al. LDH correlation with survival in advanced melanoma from two large, randomised trials (Oblimersen GM301 and EORTC 18951). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(10):1807–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hersey P, Watts RN, Zhang XD, et al. Metabolic approaches to treatment of melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(21):6490–6494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Semenza GL, Jiang BH, Leung SW, et al. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(51):32529–32537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaplon J, Zheng L, Meissl K, et al. A key role for mitochondrial gatekeeper pyruvate dehydrogenase in oncogene-induced senescence. Nature. 2013;498(7452):109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499(7457):214–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.