Abstract

While studies have found correlations between rates of incarceration and STIs, few have explored the mechanisms linking these phenomena. This qualitative study examines how male incarceration rates and sex ratios influence perceived partner availability and sexual partnerships for heterosexual Black women. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 33 Black women living in two US neighbourhoods: one with a high male incarceration rate and an imbalanced sex ratio (referred to as “Allentown”) and one with a low male incarceration rate and an equitable sex ratio (referred to as “Blackrock”). Data were analysed using grounded theory. In Allentown, male incarceration reduced the number of available men; participants largely viewed men available for partnerships as being of an undesirable quality. The number and desirability of men impacted on the nature of partnerships such that they were shorter, focused on sexual activity, and may be with higher risk sexual partners (e.g. transactional sex partners). In Blackrock, marriage rates contributed to the shortage of desirable male partners. By highlighting the role that the quantity and quality of male partners has on shaping sexual partnerships, this study advances current understandings of how incarceration and sex ratios shape HIV- and STI-related risk.

Keywords: HIV/STIs, African-Americans, incarceration, sexual behaviour, qualitative methods

Introduction

Compared to women of other races/ethnicities in the USA, Black women are disproportionately affected by HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010a). In 2010, Black women accounted for roughly 66% of all new HIV infections among women, a rate that is 20 times that of White women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010b). In that same year, the rate of gonorrhoea among Black women was 16.2 times the rate among White women; the rate of Chlamydia was over 7 times the rate for White women; and the rate of primary and secondary syphilis was 21 times the rate for White women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010a).

Racial disparities evident in HIV and STI trends are mirrored in national incarceration trends. The USA incarcerates more adults per capita than any other country in the world, however, the burden falls disproportionately on Black men (The Sentencing Project 2010). In 2011, Black men were imprisoned at a rate that was more than six times higher than that of their White counterparts (3,023/100,000 vs. 478/100,000) (Carson 2012). Notably, Black men have substantially higher incarceration rates than Black women: in 2011, there were roughly 21 incarcerated Black men for every incarcerated Black woman (Carson 2012). Gender differences in incarceration rates contribute to sex ratio imbalances already evident among Black adults (caused in part, by increased Black male mortality (Geronimus 1996)): in 2011 there were roughly 91 Black men living in the community (i.e., not behind bars) for every 100 Black women living in the community (U.S. Census Bureau 2007–2011).

Several quantitative studies have found that geographic areas with higher incarceration rates have higher and increasing rates of STIs, including HIV (Thomas and Sampson 2005; Thomas and Torrone 2006; Thomas et al. 2007). A growing body of research has explored the pathways through which incarceration influences HIV/STI transmission (Khan et al. 2009; Knittel et al. 2013; Pouget et al. 2010; Thomas et al. 2007), however, these studies largely focus on the experiences of formerly incarcerated men and/or their sexual partners. We were able to identify only one other study that empirically examined the pathways through which high male incarceration rates and the subsequent low sex ratio (i.e. more women than men) influence the nature of sexual partnerships among Black women (Lane et al. 2004), although research has investigated how low sex ratios (also referred to as ‘male shortage’) impact on HIV/STI risk among Black women (Adimora et al. 2001; Ferguson, Quinn, and Sandelowski 2007). Most existing studies examine a shortage of men in a variety of contexts (e.g. college campuses) rather than focusing on low sex ratios as a result of male incarceration. Existing studies suggest that male shortage is directly related to men having multiple and concurrent (or overlapping) sex partners (Adimora et al. 2001; Ferguson, Quinn, and Sandelowski 2007). Qualitative findings propose that male shortage can lead to concurrent sex partners and increased sexual risk by increasing the number of available female sexual partners, and by undermining women’s ability to negotiate monogamous relationships with their partners (Adimora et al. 2001; Ferguson, Quinn, and Sandelowski 2007). While these studies inform current understandings of the pathways through which imbalanced sex ratios impact sexual partnerships, the mechanisms through which high male incarceration rates and male shortage together influence the nature and type of partnerships among Black women warrants further attention.

The purpose of this paper is to examine and compare the unique processes through which rates of male incarceration and low male to female sex ratios influence perceived partner availability and the nature and structure of partnerships from the perspectives of heterosexual Black women. This study contributes to an emergent body of literature exploring the pathways through which community-level male incarceration influence heterosexual women’s individual partnerships and sexual behaviour.

Methods

Sampling

This study sampled two units of analysis: census tracts within the Atlanta metropolitan statistical area (MSA) and women living within these census tracts.

Census Tracts

We sought to study women living in two types of census tracts in the Atlanta MSA: one tract that had a high male incarceration rate and low male: female sex ratio and another tract that had a relatively low male incarceration rate and more balanced sex ratio. 2009 incarceration rates were calculated by dividing the number of incarcerated men by the tract’s adult male population (18–64 years) annually; data on the number of incarcerated men were obtained from Georgia’s Department of Correction (GA DOC). Sex ratios were calculated using data from 2007–2011 American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau 2007–2011). We identified census tracts that had either low (less than .70) or equitable sex ratios (approximately 1.0). Furthermore, we examined the rates of male incarceration in these two groups of census tracts in order to distinguish one as low and the other as high. Both census tracts had a high proportion of Black residents (>75%). While all attempts were made to identify two census tracts in Atlanta’s urban core, it was impossible to locate a predominately Black census tract in the city that had a low incarceration rate and equitable sex ratio. As a result, the tract with low incarceration rates and balanced equitable sex ratios, referred to here as “Blackrock”, was located in the suburbs and served as a comparison tract. The other tract, referred to here as “Allentown”, was located in the urban core.

Due to the suburban geography of Blackrock, and participant’s description of their neighbourhood boundaries, and neighbourhood structure (i.e. layout of commercial and residential areas), the boundaries of Blackrock were expanded to include women who lived just outside the census tract’s borders but whose “activity space” (pg. 240), or the local areas where people travel to during their daily activities (Golledge and Stimson 1987), were concentrated within the tract’s boundaries. The first author used a grounded knowledge of local businesses, places of worship, schools, government services, and parks to expand the tract’s boundaries. Allentown’s recruitment area was not similarly expanded because the neighbourhood’s structure (e.g. street networks) created geographic boundaries containing the neighbourhood and because participants qualitatively described neighbourhood boundaries that largely aligned with administratively defined boundaries.

Study Participants within Census Tracts

Eligibility

Women were eligible if they self-identified as Black/African American, heterosexual, unmarried, 18 to 39 years old, had had sex with a man in the past 90-days, resided in their sampling area for ≥ 3 years prior to the screening, and spoke fluent English. In line with theoretical sampling methods (Marshall 1996), we sought to create a sample of women that varied with regard to characteristics that might be salient to the relationships among sex ratios and the nature and structure of partnerships including: age and whether the participant cared for a child. After recruitment began, we expanded our sampling criteria to include women who engaged in transactional sex relationships and whether the participant had a partner who was incarcerated during their relationship. Eligibility was assessed through a brief screening process.

Recruitment

Women were recruited using passive and snowball recruitment methods. Flyers describing the study were posted at various organisations, businesses, and places of worship in each tract. Additional participants were recruited using snowball sampling methods, in which a community recruiter or study participant (a ‘seed’) was asked to invite individuals from their social network to be screened for eligibility for the study. Referral chains were limited to three study participants in order to prevent a large proportion of participants coming from one social network. Seeds and community recruiters were given $5 for each eligible person they referred who participated in the study.

Data Collection Procedures

One-on-one semi-structured interviews (lasting between 60 and 90 minutes) explored participants’ perceptions of neighbourhood rates of male incarceration, sex ratios, partner availability, and the nature and structure of sexual partnerships in the context of local male incarceration rates and sex ratios. Neighbourhoods were defined subjectively: participants described the boundaries of the geographic area around the place where they lived, including local places where the participants ate, shopped, and spent their free time. Participants from Allentown described neighbourhood boundaries that largely aligned with administratively defined boundaries. Neighbourhood boundaries described by Blackrock participants varied; some participants perceived their neighbourhood to be limited to the immediate area around their street or subdivision while others described an area beyond than the administratively defined boundaries. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

After the interview a short interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to assess sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. Participants received $30 and a resource guide for her contribution to the study.

Because sociodemographic data were unavailable for the participants’ subjectively defined neighbourhoods, we used data from the American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau 2007–2011) to assess characteristics of the census tracts. These were: percentage of residents living in poverty, median household income, and median age.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data were analysed using grounded theory methods and consisted of three main processes: 1) open coding, in which data are examined, compared, and categorised, 2) axial coding, in which categories are refined by examining causal conditions, and 3) selective coding, in which main categories are developed and all other categories are related to the main category/ies by examining intersections (Strauss and Corbin 1998). An initial codebook was developed based on the semi-structured interview guide and interview transcripts. To improve inter-rater reliability, two initial interviews were open coded by the first author (ED) and a co-author (LO). In order to improve reliability and to ensure adequate inter-coder agreement, coding patterns were compared and the codebook was refined until consensus was reached. To code for themes unique to participants in Blackrock, the codebook was revisited and revised when coding the first three interviews from that tract. The remaining interviews were double-coded in a similar fashion and the codebook was reviewed and revised throughout the analysis process. Memos developed categories and highlighted connections between categories and sub-categories. Quotations were compiled to illustrate concepts and relationships pertinent to core categories. During the axial and selective coding process, findings from each census tract were compared to identify similarities and differences in the mechanisms through which local male incarceration rates and male shortage influenced perceived partner availability and the nature and structure of partnerships. Member checks were conducted to enhance the findings’ interpretive validity (Maxwell 1996). MAXQDA was used to facilitate qualitative analyses (VERBI Software 2013). Descriptive statistics were generated for quantitative data using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, N.C.).

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Census Tracts

While census tracts were selected based on sex ratios and male incarceration rates, the sampled census tracts also differed across a number of other sociodemographic characteristics. In Allentown, 12% of adult men were incarcerated, and there were 70 men for every 100 women (Table 1). In Blackrock, less than one (0.89) man of every 100 was incarcerated, and there were 96 men for every 100 women. Notably, residents in Allentown were more impoverished (37.2% versus 7.6% lived below the poverty line), older (median age: 45 years versus 31 years), and had a lower median household income ($19,529 versus $69,387) than residents living in Blackrock. Nearly all residents in Allentown and Blackrock were Black (99% and 96% respectively) (U.S. Census Bureau 2007–2011).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the two census tracts located in the Atlanta, GA Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) from which participants were sampled

| Allentown | Blackrock | Atlanta MSA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | |||

| Male:female sex ratio (for individuals ≥18 years) | 0.70 | 0.96 | 0.92 |

| Male Incarceration Rate (per 100 men 15 to 64 years old) | 12 | 0.89 | 0.43 |

| Percent who are non-Hispanic Black/ African-American | 99.3% | 96.0% | 33.2% |

| Median Age | 45.0 | 30.7 | 34.7 |

| Percent living in poverty | 37.2% | 7.6% | 13.5% |

| Median household income | $19,529 | $69,387 | $57,783 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2007–2011 American Community Survey; Georgia Department of Corrections, 2009.

Sociodemographic and Sexual Risk Characteristics of the Participants

Thirty-three women took part in the study; 20 from Allentown and 13 from Blackrock. Fewer participants were interviewed from Blackrock because saturation of themes was reached earlier in the data collection process. The median age of participants in both census tracts was approximately 30 years (Table 2). Consistent with the tract-level socioeconomic differences, participants from Allentown were more impoverished and less educated than participants from Blackrock: 15/20 Allentown participants had an annual household income under $10,000 compared to only 1/13 Blackrock participants. Allentown women were also more likely to be mothers than Blackrock women (16/20 versus 6/13, respectively).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and sexual risk characteristics of study participants sampled from two census tracts located in the Atlanta, GA Metropolitan Statistical Area (N=33)

| Allentown (n=20) |

Blackrock (n=13) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Median (range) or n (%) | |

| Median Age (years) | 30.5 (19-39) | 30 (18-39) |

| Education Level | ||

| < High school | 7 (35.0%) | --- |

| High school diploma/ GED | 8 (40.0%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| Some college/Associate Degree/Trade School | 4 (20.0%) | 7 (53.9%) |

| Bachelor Degree/Any Graduate Education | 1 (5.0%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| Annual Household Income | ||

| $0 to $9,999 | 15 (78.9%)* | 1 (7.7%) |

| $10,000 to $19,999 | 1 (5.3%)* | 6 (46.2%) |

| $20,000 to $29,999 | 3 (15.8%)* | 3 (23.1%) |

| $30,000 or up | --- | 3 (23.1%) |

| Number of Children | ||

| 0 | 4 (20.0%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| 1–2 | 8 (40.0%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| 3–4 | 3 (15.0%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| ≥5 | 5 (25.0%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Percentage who reported having a sexual partner in the last three months, by partner type | ||

| Primary | 20 (100.0%) | 13 (100.0%) |

| Casual | 3 (15.0%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Paying | 4 (20.0%) | 1(7.7%) |

| Number of male sexual partners in the last year | 2 (1–10) | 2 (1–3) |

| Partner concurrency | ||

| Yes | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (30.77%) |

| Had a sex partner(s) in the last six months, who was ≥5 years older | ||

| Yes | 17 (89.5%)* | 5 (38.5%)** |

| Sexual partner who was ever incarcerated | ||

| Yes | 16 (80.0%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Sexual partner who was incarcerated during their relationship | ||

| Yes | 11 (55.0%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Sexual partner who is currently incarcerated | ||

| Yes | 3 (15.0%) | 2 (15.4%) |

Note:

n=19;

n=13.

Participants in both census tracts reported having at least one primary sexual partner (i.e. male partners with whom the participant has an emotional bond with and with whom they had recurrent sex) (Table 2). Generally, participants from Allentown reported having riskier sexual partners (e.g. higher number of sexual partners with a history of incarceration, sexual partners who paid for sex) than participants from Blackrock, however, a higher percentage of women from Blackrock reported engaging in concurrent partnerships (Table 2).

Overview of Findings

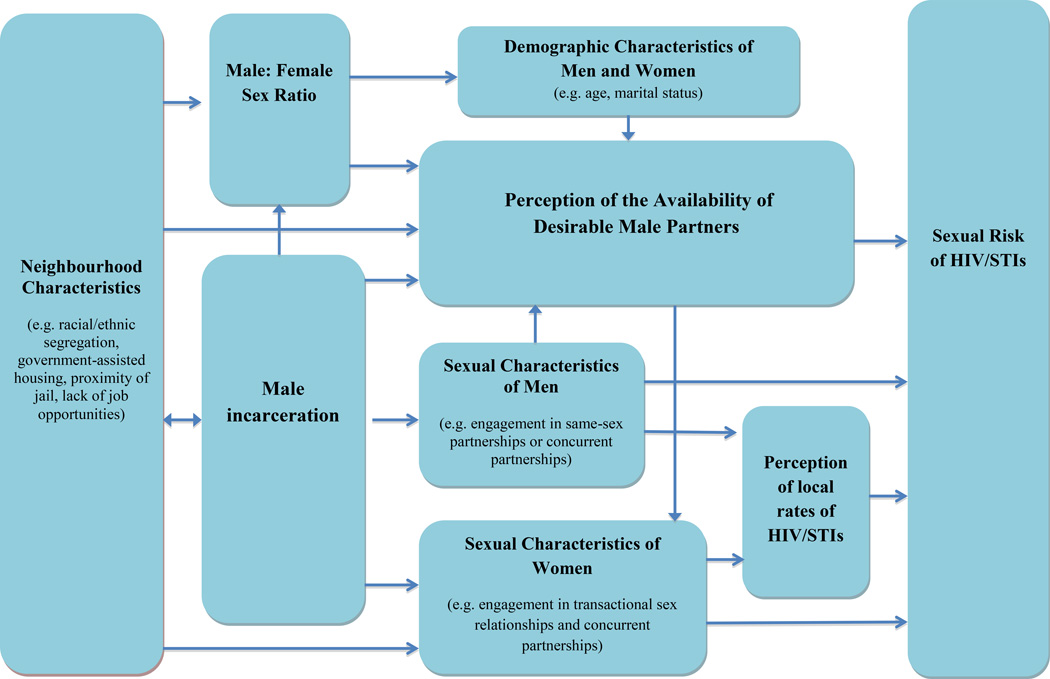

We identified three major pathways through which male incarceration rates and sex ratios contribute to HIV- and STI-related risk. From women’s perspectives, high incarceration rates and low sex ratios reduced the number of available, desirable male partners, impacted the structure and purpose of partnerships, and influenced the risk characteristics of male sexual partners (Figure 1). Another aspect of the social environment, local marriage rates, also contributed to low local sex ratios.

Figure 1.

Processes through which male incarceration and sex ratios influence sexual risk of heterosexual African American women in two Atlanta census tracts: one with high rates of male incarceration and an imbalanced sex ratio (Allentown) and one with a lower rate of male incarceration and a sex ratio close to 1.0 (Blackrock).

Male Incarceration

Consistent with data from the GA DOC, all Allentown participants reported that a large number of local men were incarcerated. Allentown participants’ understanding of high local rates of male incarceration was complex. They recognised the influences of individual-level (e.g. criminal activity), community-level (e.g. pervasive police presence), and societal-level factors (e.g. lack of economic opportunities) in shaping these rates. Participants were most likely to mention the high prevalence of drug-related and violent crimes occurring in their neighbourhood. Although participants in Allentown widely acknowledged that the neighbourhood was crime-ridden, the constant police presence was believed to make it easy for men in the neighbourhood to be detained or arrested for any illegal activity or for engaging in daily activities (e.g. loitering):

The police are out here 24/7. So it’s easy to get caught doing anything wrong in this neighbourhood. (Shantele, Allentown resident, 19 years)

Lastly, nearly all participants described the lack of economic opportunities, a consequence of both the economic downturn and employment restrictions against individuals with a criminal background, as a factor leading local men to commit crimes. Men were believed to commit crimes to augment income earned from low-wage positions or to have direct access to basic necessities including food and shelter. Said one participant:

Some of them don’t have nowhere to go, so they are getting locked up just to eat or you know have somewhere to sleep. (Keisha, Allentown resident, 39 years)

Participants stated that in addition to having large numbers of local men behind bars at any given time, men were also likely to be incarcerated repeatedly. Having a history of incarceration limited men from finding legal employment, and instead they would continue engaging in activities that led to their initial incarceration. Allentown is located in an urban area within walking distance to a local jail; a factor that contributed to the number of local men with a criminal record. Recently released men who had nowhere to go, or who lacked the financial resources to return to their own neighbourhoods, could walk easily to this neighbourhood. As a result, many of these men ended up getting ‘stuck’ and temporarily, or permanently, residing in Allentown. Many formerly incarcerated men were thought to resume the criminal activities that originally led to their incarceration. Returning to jail or prison was believed to be such a common occurrence that one participant reported that men in the neighbourhood sometimes referred to their periods of incarceration as “vacation” (Gloria, Allentown resident, 26 years).

Despite having lower rates of incarceration, roughly half of the participants from Blackrock felt that a large number of men from their neighbourhood were incarcerated. Similar to Allentown, participants in Blackrock perceived local male incarceration rates to be the result of overly-aggressive law enforcement practices and crimes being committed due to a lack of economic opportunity. Unlike Allentown, however, the types of crimes committed in Blackrock were largely described as non-violent. The remaining participants believed that few men were incarcerated in their neighbourhood. These women described local men as hardworking, gainfully employed, or in search of legal employment opportunities:

Most of the men over here are working men… They’re not like street thugs or anything like that… even if they don’t have a job, they make a job. I notice that they cut grass, they find things to do. (Jada, Blackrock resident, 38 years)

There were subtle differences between Blackrock participants who believed there to be lower rates of male incarceration and those who believed their local male incarceration rates to be high. A few of the women who believed that incarceration rates were low had lived in the neighbourhood for several years and felt that local male incarceration rates had dropped significantly during that time. The majority of Blackrock women who believed incarceration rates to be lower, however, moved to the area from a neighbourhood where crime and incarceration rates were higher.

Local sex ratios

The majority of women from Allentown believed that there were more women than men living in the neighbourhood. Participants almost exclusively linked the lack of local men to two factors: incarceration and death. One participant explained local sex ratios in the following way:

A lot of men are in jail or dead, so, you know, it’s definitely a lot, a lot of women and not enough men. (Aliyah, Allentown resident, 31 years)

A small minority of women felt that despite high local rates of male incarceration, men routinely cycled in and out of their neighbourhood from jail or prison; resulting in a constant, albeit variable, source of male partners. One participant noted that:

I mean it’s like some go in and some get out [of jail]. So it is like always a balance (Zari, Allentown resident, 24 years).

The majority of women from Blackrock described the sex ratio in their neighbourhood as either being equitable or as having more women than men. Women in both subsets reflected on male shortage in Atlanta and Georgia more broadly. However, only women who perceived their neighbourhoods to have more women than men used this knowledge to inform their understanding of local sex ratios. Women in this subset identified more mechanisms through which they found potential male partners (e.g. looking outside of their neighbourhood) than women who perceived sex ratios to be equitable or to have more men than women.

With the exception of one woman, participants from Blackrock who perceived there to be a low local sex ratio were similar to those from Allentown; citing male incarceration as one of the biggest contributing factors to male shortage. Only one additional factor, the presence of publicly-subsidised housing, was described as contributing to the local sex ratio, by increasing the number of women living in the neighbourhood.

Availability of desirable male partners

Regardless of their perception of the local sex ratio, women in Allentown largely agreed that most available men were undesirable. Participants defined undesirable men as men who were unemployed or unmotivated to work, immature, not interested in a committed relationship, or who were physically, verbally, or sexually abusive. Notably, one characteristic that was not viewed as a deterrent was having a history of incarceration. Many participants felt that because so many men had criminal histories that if they wanted any type of romantic or sexual relationship that they could not exclude men with a history of incarceration.

Women in Allentown, however, did perceive low local male to female sex ratios to have a greater impact on the availability of certain groups of men. Specifically, women described a paucity of desirable available men in their age range. Overwhelmingly women felt that local available men were either too young (≤22 years) or too old (≥45 years).

Younger men were perceived as being undesirable because they were involved in criminal and violent behaviour and thought to be selfish (i.e. concerned with their own interests instead of the interests of their partner or the partnership more generally). Due to this perception, many women sought out older partners. There were many reasons that women gave for seeking older men including “no drama, no none of that” (Zari, Allentown resident, 24 years) being financially stable, monogamous, and more understanding. One participant described her own and other local women’s interest in dating an older man as opposed to a younger man when noting:

Older dudes they understand women, young boys they don’t…Sexually, moneywise, you know business wise, talking to it, like feelings and all, they know how to treat a woman. (Dana, Allentown resident, 19 years)

While older men were generally sought out as romantic partners some women believed that they were not as readily available as younger men; older men were believed to live on the periphery of the neighbourhood. Regardless of their physical location, a participant’s age influenced her perception of whether older men were available for romantic partnerships with them. Older men were perceived to only make themselves available to younger women living in the neighbourhood. Partnerships between older men and younger women were viewed as fulfilling a specific purpose for both partners. For young women, older men provided financial stability and material support; for older men, young women provided sexual activity.

Women in Allentown cited three additional factors as contributing to the shortage of desirable available male partners: local rates of HIV/STIs, men engaging in concurrent and multiple partnerships, and men engaging in same-sex sexual behaviour. There was a perception among Allentown participants that the high prevalence of HIV/STIs locally was caused, in part, by men engaging in multiple and concurrent sexual partnerships; a perceived neighbourhood norm. Finally, many women in Allentown discussed the occurrence of men engaging in same-sex relationships, “a common thing in the area” (Renelle, Allentown resident, 22 years), that they felt contributed to a reduced number of desirable available male partners. Due to these experiences and perceptions, women were hesitant to engage in sexual relationships with men from the neighbourhood.

Regardless of their perception of local sex ratios, women in Blackrock were similar to women in Allentown in their perception of the availability of desirable men for partnerships. Women in this tract described men who were available for partnerships locally as being of a lower quality. The characteristics that made men undesirable to women in Allentown were echoed by women in Blackrock (e.g. violent, non-monogamous). Women in Blackrock differed from women in Allentown, however, with regards to their perception of the factors that reduced the number of desirable available male sexual partners. All women in Blackrock referenced the number of married men living in their neighbourhood as reducing the number of single and desirable men available for partnerships. One woman’s comments summarised common perceptions of local marriage rates:

A lot of guys in this area who…are already married and so of course, that’s out…The kind of guy that I think that I would like…you know they kind of already married. (Amira, Blackrock resident, 30 years)

Outside of local marriage rates, there were a myriad of factors Blackrock women cited as contributing to reducing the perceived number of desirable available male partners, however, there was little consensus about the main issues. Much like participants from Allentown, some participants in Blackrock believed that there were men in the neighbourhood engaging in same-sex sexual behaviour. An additional factor, unique to women living in Blackrock, was the perception that the racial/ethnic segregation of the neighbourhood reduced the perceived number of desirable available male partners. Some women believed that because the residents of their neighbourhood were predominantly Black and that other racial/ethnic groups tended to “stay in their separated area” (Malia, Blackrock resident, 31 years) that they had limited access to desirable available men of other racial/ethnic backgrounds; limiting their overall pool of male partners.

Partnership characteristics

In Allentown, male incarceration and the availability of desirable male partners influenced the structure and type of partnerships that participants sought out, experienced, and witnessed. While a history of incarceration was not exactly considered to be undesirable it seemed to influence the type of relationship that women were interested in with that partner. For example, one participant would not rule out dating a man with a record, but would not pursue a serious relationship with him due to a fear that he may still be involved in activities that lead to his initial incarceration. She describes this by stating:

[His incarceration history] was what kept me from getting serious with him because he tends to have patterns to where he makes dumb decisions to end right back in prison. So I can handle jail maybe, but when you keep going in and out of prison for long periods of time, I’m not too big on that. (Shantele, Allentown resident, 19 years)

Generally, relationships with men with a record seemed to be characterised as short, based primarily on sexual activity, and often overlapped with other sexual partnerships that the man might be engaged in. These relationships occurred in a sexual network environment described by women as a “spider web,” (Gloria, Allentown resident, 26 years) where sexual connections were interrelated and overlapping. Local rates of male incarceration were believed to influence concurrency by destabilising existing sexual partnerships, or “foundation relationships” (Candice, Allentown resident, 32 years). In a partner’s absence women were thought to seek out additional partners.

The exceptions to this were women whose partners were incarcerated briefly. The burden that this period of incarceration placed on the relationship was chiefly financial (e.g. paying bail) and did not contribute to a substantial disruption in the nature of the relationship. Longer periods of incarceration, however, were frequently cited as a contributing factor to a male partner’s interest in engaging in multiple sexual partnerships upon his release. Said one participant of her relationship with a man who recently served four years:

[His incarceration] kind of had an impact on why our relationship didn’t last long. Because he had just spent the last four years in prison so now he has his freedom to do what he wants to do [sexually]. (Nyah, Allentown resident, 26 years)

Participants emphasised that it was common for women in Allentown to engage in transactional sex relationships (or to exchange sex for financial or material support) during their partners’ incarceration. These relationships were thought to provide much-needed financial and material support when a primary partner was absent. Money earned from these exchanges was sometimes used to defray the costs associated with a partner’s incarceration. Summarising these costs one 21-year old participant revealed “[incarceration] costs me money. Lawyers, bonds, books, phones” (Ayesha, Allentown resident, 21 years). Transactional sex was also viewed as a mechanism through which women could obtain “fast” cash, allowing them to provide largely uninterrupted care for their children without incurring childcare expenses. Describing the relationship between local male incarceration rates and transactional sex relationships one participant stated:

The man in jail, that’s why the womens out here are prostituting… Cuz the man in jail, they can’t do nothing…And they have so many children, they don’t have no money to pay no babysitter so they got to make some money to better provide for them. (Candice, Allentown resident, 32 years)

There were other scenarios where women reported engaging in transactional sex relationships. For women with partners with a criminal record but who are not currently incarcerated, income from transactional sex relationships helped provide financial stability for their household. A lack of employment opportunities for women and the employment restrictions against individuals with a criminal background (their male partners) contributed to a situation where women felt that if they “can’t get no job, I might as well use what I got” (Laila, Allentown resident, 28 years).

One of the consequences of the seemingly high prevalence of women engaging in transactional sex in Allentown was the perception that this contributed to the high neighbourhood prevalence of HIV/STIs (described above).

Some men will go out there and pay for it [sex], which is most definitely why diseases will come back. (Ayesha, Allentown resident, 21 years)

In Blackrock, the structure and type of partnerships that women sought out, experienced, and witnessed were also influenced by the perceived local availability of desirable male partners. The one factor that all participants agreed influenced the perceived number of available desirable male partners in the neighbourhood was local marriage rates. While a man’s marital status influenced a participant’s romantic interest (or lack thereof) in him, it did not seem to deter married men from pursuing romantic relationships with women in their neighbourhood. Moreover, participants felt that some married men did not try to hide their marital status from the women they pursued. Instead they would approach single women and offer to support them materially or financially in exchange for a romantic or sexual relationship. One woman described her experience being approached by a married man:

Married men approach me and it’s disheartening…obviously it doesn’t mean anything anymore to be married and be faithful to that one person…Yeah, [when he approached me] he was up front with it…You know… “I’m married but I’ll take care of you”. What? I was like “No thank you.” Yeah. That was someone that goes to church with me. (Cassandra, Blackrock resident, 36 years)

For women living in Blackrock the major consequence of the perceived paucity of desirable available male partners was that several women described engaging in multiple long-term concurrent relationships. For these women each long-term partner seemed to serve a specific purpose (e.g. provide love, financial support, or sex) that a single male partner was unable to provide. Blackrock participants described vacillating between partners seemingly trying to identify which partner’s “purpose” served her needs more.

I started cheating on him. I got me another boyfriend or another dude I was messing with. I was dating him, was dating both of them at the same time like [the] same day sometimes. I was there with him because he’s faithful but…I was seeking other options. (Jasmin, Blackrock resident, 30 years)

Discussion

Emerging research suggests that people living in communities with high rates of incarceration are at a higher risk of contracting HIV/STIs (Thomas and Sampson 2005; Thomas and Torrone 2006; Thomas et al. 2007) but the exact pathways through which incarceration and sex ratios contribute to HIV- and STI-related risk have not been fully explored. This qualitative study explored how male incarceration rates and resulting sex ratio imbalances impacted the nature and structure of sexual relationships to create conditions that increase the risk of HIV/STI transmission.

Participants discussed the impact that male incarceration rates and male shortage had on the perceived number and desirability of available male partners in their neighbourhood. Research has highlighted the impact that male incarceration has on the number of partners available for Black women and how male shortage shapes sexual risk (e.g., higher number of sex partners (Knittel et al. 2013; Pouget et al. 2010), multiple and concurrent partnerships (Adimora et al. 2001; Lane et al. 2004)), however, with few known exceptions (Adimora et al. 2001; Bontempi, Eng, and Quinn 2008) the perceived desirability of available partners has been absent from this discussion. Both Adimora et al. (2001) and Bontempi, Eng, and Quinn (2008) found that local sex ratios contributed to a reduction in the number of “quality” men available for partnerships; these studies did not, however, describe how partner quality shaped the nature or structure of partnerships. Our findings build on this work by highlighting how perceived partner availability and desirability shaped the nature and structure of partnerships and HIV- and STI-related risk for women engaging in relationships with either older or younger male partners.

Women engaging in sexual relationships with male partners ten or more years older than them may have an increased risk of HIV/STI infection because their partners are more likely to be infected themselves or because resulting power imbalances can impact sexual decision-making (Adimora and Schoenbach 2002). In the absence of older available men who were perceived to be worthy of a long-term or committed partnership, women discussed seeking out less desirable, often younger, men for short-term partnerships; partnerships focused on sexual activity and that were often with partners believed to have higher sexual risk (e.g. men engaged in concurrent partnerships). While this study covers a fairly wide age range, little data exists to describe differences in sexual partnership decisions by age among adults, and specifically about perceived partner availability by age. Our findings suggest that partner desirability can dictate both the type and structure of partnerships and highlight the need for additional research on heterosexual Black women’s perceptions of partner desirability and how perceived desirability impacts sexual risk throughout a woman’s life course.

Transactional sex is associated with behaviours that can increase an individual’s risk of acquiring HIV/STIs including having high-risk sexual partners, multiple sexual partners, and a high number of new sexual partners (Cederbaum et al. 2013; Baseman, Ross, and Williams 1999; Dunkle et al. 2010; McMahon et al. 2006). Additionally, some research has identified an association between engaging in transactional sex relationships with a reduction in condom use (Baseman, Ross, and Williams 1999; Dunkle et al. 2010). Our findings illuminate two pathways through which incarceration influenced women’s reliance on transactional sex relationships. First, male incarceration disrupted the economic stability of a household by removing a male partner who was providing material or financial support (Cooper et al. 2013). Second, having a criminal record served as a barrier to employment opportunities for many of the participants’ partners. Women engaged in transactional sex during periods where their partner was absent or during periods where their partner was un- or underemployed. Most studies exploring transactional sex relationships and sexual risk in the USA have been conducted among subpopulations of high-risk women (e.g., substance using women, homeless women (Cederbaum et al. 2013; McMahon et al. 2006)). One recent study, however, examined the prevalence of transactional sex among women in the general US population (Dunkle et al. 2010) and found that Black women were more likely than White women to report starting a relationship due to economic considerations and initiating transactional sex with someone who wasn’t a regular partner. Transactional sex with non-regular partners was associated with concurrent partnerships, substance use, and having high-risk sexual partners. To better understand racial/ethnic disparities in rates of HIV/STIs, future research should focus on economically motivated sexual relationships among Black women in the USA, specifically among women living in communities disproportionately impacted by incarceration.

We also found that local marriage rates influenced the perceived desirability of available male partners in Blackrock. As a result, several participants reported engaging in multiple long-term concurrent partnerships due to their inability to identify one male partner to fulfil all of their needs. Although the majority of research exploring the context and motivations for partner concurrency has focused on the experiences of men (Carey et al. 2010; Nunn et al. 2011), we identified one study that explored partner concurrency among adults recruited from an STD clinic (Senn 2011). Senn et al.’s (2011) findings suggest that there is some overlap in the reasons men and women give for engaging in concurrent partnerships, including the need for different partners to fulfil different needs. Our findings intimate that similar motivations for engaging in concurrent partnerships may exist for heterosexual Black women in areas where desirable men are believed to be less available.

Limitations

Our findings should be understood in the context of several study limitations. First, the boundaries and scales of census tracts might not accurately reflect how people experience or perceive their neighbourhood. Participants (particularly in Blackrock) described variation in their definitions of ‘neighbourhood’ which necessarily influenced their perceptions of partner availability. This is complicated by evidence that suggests that low male to female sex ratios at the census tract level are not significantly associated with more sexual partners for men or women (Senn et al. 2008) though some studies have found a relationship between tract sex ratio and sexual health outcomes (Cooper et al. 2014). In the absence of administrative data that align with participant’s perceptions of neighbourhood boundaries, however, census tracts are used frequently in studies, examining health outcomes at the neighbourhood level (Krieger 2006). Second, while every attempt was made to select two census tracts from the urban core, we were unable to identify a census tract in the urban core with a low male incarceration rate, a male: female sex ratio close to 1.00, and a high proportion of Black residents. The difficulty in identifying this type of census tract highlights the racialisation of incarceration in the USA. As a result, Blackrock was located outside of the urban core. Our findings, therefore, could be a reflection of the different perceptions that women living within and those living outside of the urban core may have of sex ratios, perceived partner availability, and romantic relationships instead of a product of their perceptions of local incarceration rates and sex ratios. Further, administratively-defined boundaries may be less relevant in suburban settings because living outside the urban core may be accompanied by greater mobility (e.g. access to transportation) outside of the neighbourhood boundaries.

This study also had several strengths. A rigorous examination of negative cases helped to refine our interpretations and member checks were used to solicit feedback about our study’s findings. Furthermore, we sought variation by tract-level rates of male incarceration and sex ratios, allowing for the contrast and comparison of research findings across census tracts. Finally, we were able to reach saturation of key analytic themes from both neighbourhoods and our findings support previous research.

Conclusions

This study contributes to an emerging body of literature examining the processes through which incarceration and sex ratios influence romantic and sexual partnerships among heterosexual Black women. The results from this body of work suggests that HIV and STI prevention efforts focusing on heterosexual Black women may be enhanced by considering the role of local incarceration rates, marriage rates, and resulting sex ratio imbalances.

In the present study, the theme of desirability emerged as a factor influencing the nature and structure of sexual partnerships in the context of high local rates of male incarceration. To better understand racial/ethnic disparities in rates of HIV/STIs, future research should focus on how perceived desirability impacts sexual risk among heterosexual Black women, specifically among women living in communities disproportionately impacted by incarceration. Furthermore, to more deeply examine the impact of local rates of male incarceration, and low male to female sex ratios on the nature and structure of partnerships, samples should include heterosexual men (both with and without a criminal history).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by a grant from the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to Emory University: 1F31MH096630-01, the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health and the Emory University, and the Laney Graduate School. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of these funders. We would like to thank study participants for sharing their time and experiences with this study.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Contextual factors and the black-white disparity in heterosexual HIV transmission. Epidemiology. 2002;13(6):707–712. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Fullilove RE, Aral SO. Social context of sexual relationships among rural African Americans. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2001;28(2):69–76. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baseman J, Ross M, WIlliams M. Sale of Sex for Drugs and Drugs for Sex: An Economic Context of Sexual Risk Behavior for STDs. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26(8):444–449. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi JM, Eng E, Quinn SC. Our Men Are Grinding Out: A Qualitative Examination of Sex Ratio Imbalances, Relationship Power, and Low-Income African American Women's Health. Women and Health. 2008;48(1):63–81. doi: 10.1080/03630240802132005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Senn TE, Seward DX, Vanable PA. Urban African-American Men Speak Out on Sexual Partner Concurrency: Findings from a Qualitative Study. AIDS Behaivor. 2010;14:38–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9406-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson EA, Sabol WJ. Prisoners in 2011. edited by Bureau of Justice Statistics U.S. Department of Justice. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum JA, Wenzel SL, Gilbert ML, Chereji E. The HIV Risk Reduction Needs of Homeless Women in Los Angeles. Women's Health Issues. 2013;23(3):e167–e172. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Disparities in HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STDs, and TB: African Americans/Blacks. [Accessed December 1];2010a http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthdisparities/AfricanAmericans.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans. [Accessed December 1];2010b http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/index.htm.

- Cooper HLF, Clark CD, Barham T, Embry V, Caruso B, Comfort M. "He Was the Story of My Drug Use Life" : A Longitudinal Qualitative Study of the Impact of Partner Incarceration on Substance Misuse Patterns Among African American Women. Substance Use and Misuse. 2013;49(1–2):176–188. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.824474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HLF, Haley DF, Linton S, Hunter-Jones J, Martin M, Kelley ME, Karnes C, et al. Impact of public housing relocations: are changes in neighborhood conditions related to STIs among relocaters? Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2014;41(10):573–579. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Wingood GM, Camp CM, DiClemente RJ. Economically motivated relationships and transactional sex among unmarried African American and white women: results from a U.S. national telephone survey. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(Suppl 4):90–100. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson YO, Quinn SC, Sandelowski M. The gender ratio imbalance and its relationship to risk of HIV/AIDS among African American women at historically black colleges and universities. AIDS Care. 2007;18(4):323–331. doi: 10.1080/09540120500162122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, HIllemeier MM, Burns PB. Excess Mortality Among Blacks and Whites in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(1552–8) doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611213352102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golledge RG, Stimson RJ. Analytical Behavioural Geography. New York: Croom Helm; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MR, Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Epperson MW, Adimora AA. Incarceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(4):584–601. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9348-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knittel AK, Snow RC, Griffith DM, Morenoff J. Incarceration and sexual risk: Examining the relationship between men's involvement in the criminal justice system and risky sexual behavior. AIDS Behavior. 2013;17:2703–2714. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0421-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. A Century of Census Tracts: Health and the Body Politic (1906–2006) Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(3):355–361. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9040-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SD, Keefe RH, Rubinstein RA, Levandowski BA, Freedman M, Rosenthal A, Cibula DA, Czerwinski M. Marriage Promotion and Missing Men: African American Women in a Demographic Double Blind. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2004;18(4):405–428. doi: 10.1525/maq.2004.18.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice. 1996;13(6):522–525. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.6.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design: an interactive approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon JM, Tortu S, Pouget ER, Hamid R, Neaigus A. Contextual determinants of condom use among female sex exchangers in East Harlem, NYC: an event analysis. AIDS Behavior. 2006;10(6):731–741. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Dickman S, Cornwall A, Rosengard C, Kwakwa H, Kim D, James G, Mayer KH. Social, structural and behavioral drivers of concurrent partnerships among African American men in Philadelphia. AIDS Care. 2011;23(11):1392–1399. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.565030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget ER, Kershaw TS, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR, Blankenship KM. Associations of sex ratios and male incarceration rates with multiple opposite-sex partners: potential social determinants of HIV/STI transmission. Public Health Report. 2010;125(Suppl 4):70–80. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Scott-Sheldon LA, Seward DX, Wright EM, Carey MP. Sexual partner concurrency of urban male and female STD clinic patients: a qualitative study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):775–784. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Urban MA, Sliwinski MJ. Male-to-Female Ratio and Multiple Sexual Partners: Multilevel Analysis with Patients from an STD Clnic. AIDS Behav. 2008;14(4):942–948. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9405-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The Sentencing Project. Incarceration in the United States. [Accessed June 26];2010 http://www.sentencingproject.org/template/page.cfm?id=107. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Torrone E. Incarceration as forced migration: Effects on selected community health outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(10):1762–1765. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Sampson LA. High rates of incarceration as a social force associated with community rates of sexually transmitted infection. Journal of Infectious Disease. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S55–S60. doi: 10.1086/425278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Levandowski BA, Isler MR, Torrone E, Wilson G. Incarceration and Sexually Transmitted Infections: A Neighborhood Perspective. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;85(1):90–99. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. [Accessed September 1];2007–2011 http://factfinder2.census.gov.

- MAXQDA, software for qualitative data analysis, 1989–2013. Berlin, Germany: [Google Scholar]