Abstract

Choice viewing behavior when looking at affective scenes was assessed to examine differences due to hedonic content and gender by monitoring eye movements in a selective looking paradigm. On each trial, participants viewed a pair of pictures that included a neutral picture together with an affective scene depicting either contamination, mutilation, threat, food, nude males, or nude females. The duration of time that gaze was directed to each picture in the pair was determined from eye fixations. Results indicated that viewing choices varied with both hedonic content and gender. Initially, gaze duration for both men and women was heightened when viewing all affective contents, but was subsequently followed by significant avoidance of scenes depicting contamination or nude males. Gender differences were most pronounced when viewing pictures of nude females, with men continuing to devote longer gaze time to pictures of nude females throughout viewing, whereas women avoided scenes of nude people, whether male or female, later in the viewing interval. For women, reported disgust of sexual activity was also inversely related to gaze duration for nude scenes. Taken together, selective looking as indexed by eye movements reveals differential perceptual intake as a function of specific content, gender, and individual differences.

Keywords: Emotion, Scene, Eye movements, Selective looking, Pupil

1. Introduction

Affective cues in the visual field naturally draw and hold attention (e.g., Calvo and Lang, 2004; Rösler et al., 2005; LaBar et al., 2000; Nummenmaa et al., 2009) and we have interpreted this “natural selective attention” as reflecting activation of appetitive and defensive neural systems that have evolved to engage attention and arousal in the service of selecting an appropriate action (Bradley, 2009; Lang et al., 1997). Whereas initial attention capture is typically conceptualized as a relatively reflexive process, sustained processing of emotion-inducing cues, particularly in terms of continued perceptual intake, should reflect different functional responses that are optimal in specific affective contexts. In the current study, we monitored eye movements in a choice viewing paradigm which presented a pair of pictures (3 s) in which an affective “content” picture depicted either bodily mutilation, contamination, human threat, appetizing food, nude males, or nude females, together with a “control” picture that was always neutral in hedonic valence. The direction and duration of eye fixations on each picture in a pair were measured across the viewing interval as men and women looked at specific affective contents.

Scenes of both contamination (e.g., feces, vomit, etc.) and mutilation reliably elicit descriptions of disgust (Bradley et al., 2001b; Libkuman et al., 2007), which is classically conceptualized as a rejection response (evolutionarily associated with oral rejection of bad food; Rozin et al., 2000), which could prompt perceptual avoidance. On the other hand, some studies of attentional bias report greater exogenous attention capture for disgusting, compared to fear, stimuli. In these studies (see Carretié, 2014, for an overview; Carretié et al., 2011), emotional stimuli are presented as irrelevant distractors in the context of an ongoing primary task, and attention capture inferred by disruption of task performance (i.e., speed or accuracy). For example, Cisler et al. (2009) reported poorer accuracy on primary task performance 480 ms following the presentation of a disgust, compared to a fear, word, but not earlier or later. Using disgusting and fearful pictures (rather than words), van Hooff et al. (2013) reported reduced detection accuracy for probes presented in the context of disgusting, compared to fear, scenes, but only when presented 200 ms after picture onset, leading them to suggest that attention capture for disgust stimuli is a briefly-lived phenomenon. In the current study, we assessed gaze duration for scenes of contamination and mutilation as it varied across a 3 s interval, predicting relative rejection or avoidance following initial attention capture.

Attentional bias studies have also reported that, compared to other pleasant scenes, sexually-provocative distractors also reduce primary task performance (see Carretié, 2014). Moreover, erotic scenes prompt enhanced sympathetic activity, measured by skin conductance or pupil diameter (e.g. Lang, Greenwald, Hamm & Bradley, 1993; Bradley et al., 2001a; Bradley et al., 2008) and a number of studies have outlined differences among men and women when viewing sexual stimuli (see Murnen and Stockton, 1997; Rupp and Wallen, 2008; Koukounas and McCabe, 1997; Steinman (1981)). In general, whereas biological measures of sexual arousal are often similar, men tend to report that scenes of opposite-, compared to same sex-nudes, are more arousing (Bradley et al., 2001b; Chivers et al., 2010; Jansson et al., 2003), whereas women do not always show a clear preference (Chivers et al., 2004; Costell et al., 1972). Experimental studies, however, have typically not given participants an explicit choice in terms of voluntarily sustaining or averting gaze by providing an alternative visual stimulus. In the current study, we assessed gender differences in choice viewing by presenting scenes depicting either opposite- or same-sex nudes paired with neutral control pictures to both men and women, and additionally measured both skin conductance and pupillary changes as indices of sympathetic nervous system activity.

Eye movement behavior, including scanning and gaze duration, is less reflexive than sympathetically-mediated autonomic responses and is clearly amenable to voluntary control. For example, Nummenmaa et al. (2006) reported that specific instructions to look at a neutral picture in a pair decreased the number and duration of fixations on the accompanying affective scene. Rinck and Becker (2006) found that spider phobics show reliably shorter sustained gaze duration on fear-related pictures, compared to non-fearful participants, and In-Albon et al. (2010) reported that children with separation anxiety were more likely to fixate scenes of separation, rather than reunion, compared to healthy children. More relevant to the current study are data indicating elevated initial fixations on scenes of contamination by participants reporting high fear of contamination (Armstrong et al., 2012). Thus, in the current study, individual differences in reported disgust of contamination, mutilation and sexual activity were measured using the Disgust Scale (Haidt et al., 2002) to assess effects on selective looking.

Several previous studies that used a selective looking paradigm specifically instructed participants to direct attention to each member of the pair (e.g., same/different valence decision; Calvo and Lang, 2004; Nummenmaa et al., 2006). In the current study, we used a free viewing (no-task) context to avoid biasing the direction and duration of eye movements. On each 3 s trial, a neutral control picture was presented with a scene that depicted contamination, mutilation, threat, appetizing food, nude males, nude females or another neutral content picture. Gaze duration for affective content pairs was compared both to eye movement behavior for pairs that contained a neutral content picture, as well as directly to the neutral control picture in each pair. To avoid effects due to the presence of a person in one member of the pair, both pictures in a pair either portrayed people or did not. To rule out differences due to color, all pictures were presented in grayscale, and mean brightness was matched for exemplars in each content category and for each pair. The dependent measure was gaze duration, defined as the sum of the fixation durations on the content picture in each pair expressed as a proportion of the total duration of eye fixations (to the content or neutral control picture in each pair) for each half-second interval across the 3 s viewing period.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Forty-two students from a University of Florida General Psychology course participated for course credit. The study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board and written informed consent obtained. Due to data loss or quality, the final N in analyses for gaze duration and pupil diameter was 39 (22 females), and for skin conductance, 40 (22 females).

2.2. Materials and design

Stimuli were pictures selected from the International Affective Picture System1 (IAPS: Lang et al., 2005) and the internet. The content pictures in each pair were a scene depicting one of 7 contents that included 8 pictures in each of 6 different affective categories: 1) contamination, 2) mutilation, 3) threat, 4) food, 5) nude males, 6) nude females, as well as 7) a set of neutral content pictures (16 pictures). These 64 pictures were paired with 64 control pictures that were always neutral in hedonic valence. Pictures were presented in pairs on each trial, with one content picture and one control picture in each pair. All pictures were presented in grayscale, with brightness adjusted in Photoshop such that mean brightness was matched for exemplars in each content group and the mean brightness did not vary as a function of scene content or pair type. Pairs were arranged such that if the content picture on a trial portrayed people, the neutral control picture also portrayed people; conversely, if the content picture did not include people, the neutral control picture did not include people. Across participants, each neutral control picture was presented in a pair that included each of the affective and neutral content pictures.

Picture presentation was controlled by an IBM-compatible computer running Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, San Francisco, CA). Pictures were displayed on a 19″ in monitor (screen size: 38 cm × 30 cm) located in the experimental room, at a distance of 89 cm from the participant. Two seconds before the presentation of each pair, a fixation cross appeared in the center of the screen and flashed 750 ms prior to picture onset to draw attention to the central fixation point prior to pair presentation. Each picture in a pair was displayed in 8-bit grayscale and subtended a visual angle of 10° (width) by 7.5° (height). The center of each picture was located at 7° of visual angle to the left or right of the central fixation cross, with 14° of visual angle from center-to-center of each pair. Each pair was displayed for 3 s and followed by a blank 3 s intertrial interval. The intertrial interval display consisted of a uniform grayscale background set to the midpoint of an 8-bit grayscale range.

Pictures were arranged in sub-blocks such that one exemplar from each of the content categories occurred twice in each sub-block, once on the left and once on the right side of the fixation point. Content pictures within each category were presented equally often on the left and right side of the fixation cross for each participant. Across participants, each neutral control picture was presented with an exemplar from each of the 7 content categories, with the restriction that pictures involving people were only paired with content pictures portraying people.

2.3. Physiological recordings

Eye movements and pupil diameter were monitored and recorded using an ASL model 504 eye-tracker system (Applied Science Laboratories, Bedford, MA) which allows free movement of the head, and consists of a video camera and an infrared light source pointed at the participant's right eye. A magnetic sensor, attached to a headband tracks and adjusts for head movement. The recording video camera was located in a box in front of the subject covered by a red translucent screen that obscured it from view. Eye position and pupil diameter were sampled at 60 Hz for 2 s prior to picture onset and for 3 s during picture onset.

Skin conductance was measured using VPM software (Cook, 1997) running on an IBM-compatible computer. Skin conductance was recorded using two large sensors placed adjacently on the hypothenar eminence of the left palmar surface after being filled with 0.05-m NaCl paste. A Coulbourn S71-22 skin conductance coupler (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) sampled electrodermal activity at 10 Hz.

2.4. Procedure

Upon arrival at the laboratory, each participant signed a consent form and was seated in a recliner in a small, sound-attenuated, dimly lit (5 lx) room. The eye tracking headband and physiological sensors were then attached, and the eye tracking equipment calibrated using a procedure in which the participant fixated a series of dots projected onto the screen in front of them. Each participant was then instructed to look at a series of pictures that would be displayed on the screen in front of them. Following the picture presentations, the participant completed a short form of the Disgust Scale (Haidt et al., 2002). The experimenter subsequently debriefed, paid, and thanked the participant.

2.5. Data reduction

Two rectangular regions of interest were defined that corresponded to the location on the screen in which each picture was presented. A fixation was defined as an eye movement that remained within 1° of visual angle for 100 ms and occurred within one of the two regions of interest. For the timing of gaze, the duration of each fixation was converted to the number of milliseconds fixated on the content or control picture in each pair in each of six, 500-ms intervals across the 3 s viewing interval, expressed as the proportion of time the eye was fixated on the content picture and the sum of the total fixation duration in each time interval. Using this metric, if the two pictures in a pair were looked at for an equivalent amount of time in any interval, gaze duration was 50%.

Pupil diameter during picture viewing was deviated from the mean pupil diameter in the 2 s baseline preceding picture onset, expressed as the mean change across the 3 s viewing interval, and averaged as a function of pair type for each participant. Skin conductance level during picture viewing was deviated from the mean level in a 1 s baseline preceding picture onset, expressed as the mean change from 1 to 6 s after picture onset, and averaged as a function of pair type for each participant.

Sixteen of the 32 items on the Disgust Scale short form (Haidt et al., 2002) were grouped into subscales based on the nature of the eliciting stimuli. Three subscales were defined that indexed: 1) disgust of bodily products (e.g., vomit, feces; 4 items), 2) disgust of situations involving blood/mutilation (4 items), and 3) disgust of sexual activities (8 items). These scores were included as continuous variables in specific analyses that assessed eye movement activity for mutilations, contamination, or sexual activity, respectively.

Multivariate statistics are reported using a threshold of p < .05.

3. Results

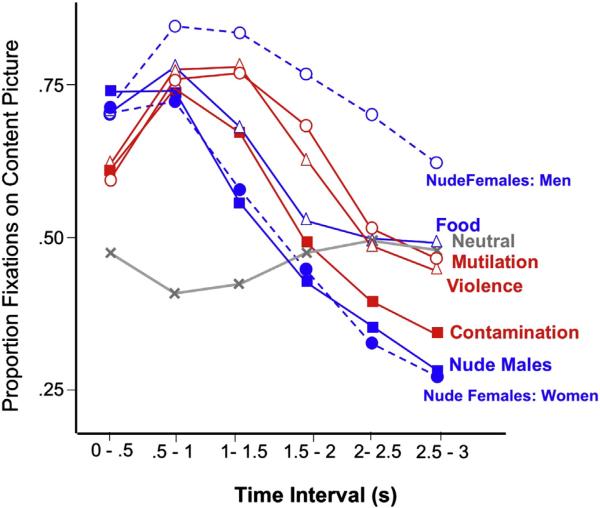

The proportion of time in each half-second interval during which the eyes were fixated on the content picture in each pair across the 3 s viewing period is illustrated in Fig. 1. A significant Gender × Content interaction, F(6, 32) = 7.1, p < .0001, was followed up by simple main effects tests which indicated that men and women only differed in gaze duration for pairs including nude females, F(1,37) = 16.4, p < .0003; accordingly, gaze duration for this content is illustrated separately for men and women in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Gaze duration on the content picture in each pair varies across the viewing interval with specific hedonic content and gender. 50% indicates that the equivalent amount of time was spent looking at the content picture and the neutral control picture in each pair.

Overall, significant main effects of hedonic Content, F(6,32) = 26.6, p < .0001 and Time, F(5,33) = 52.4, p < .0001, were accompanied by a significant interaction of hedonic Content and Time, F(6,32) = 5.2, p < .01. The simple main effect of content was significant at each time interval, Fs (6,32) = 20,48,32,8,4,5, ps < .005. Follow-up Bonferroni tests (p < .001; t(37) > 3.32) indicated that, in the first 500 ms of picture viewing, all pairs that included affective scenes prompted significantly longer gaze durations on the content picture, compared to the pairs that included only neutral pictures, as well as compared to the neutral control picture in each affective pair (i.e. >50%, Fs(1,37) > 9, ps < .01). Gaze duration for neutral content pictures, on the other hand, did not significantly differ from neutral control pictures in the pair. In addition, in the first half-second of picture viewing, gaze duration on pleasant scenes, regardless of specific content, was significantly greater than for unpleasant scenes, F(1,37) = 30, p < .0001.

In the second time interval (.5–1 s), all affective content pictures continued to show significantly longer gaze duration, compared to pairs with neutral content pictures, but differences between pleasant and unpleasant scenes disappeared. In the third time interval (1–1.5 s), gaze duration for affective pairs remained significantly greater than neutral content pictures, except for pairs including nude males, which no longer differed from neutral content pictures, but by the fourth interval (1.5–2 s), only fixations on scenes of mutilation and threat, and nude females (for men) continued to be significantly longer than for pairs with neutral content pictures.

In the last second of picture viewing (e.g., 2–2.5 and 2.5–3 s), only men looking at nude females showed gaze duration that was significantly greater than for neutral content pictures, as well as greater than the control picture in the pair, t(16) = 2.26, p < .04. More importantly, scenes of contamination and nude males were now viewed significantly less than neutral content pictures, as well as significantly less than the neutral control picture in each pair (i.e., <50%), showing avoidance for scenes of contamination, t(38) = −3.93, p < .0004, and nude males, t(38) = −4.45, p < .0001. Women, on the other hand, also avoided looking at female nudes late in the viewing interval, with significantly longer gaze duration on the neutral control picture in the pair, t(38) = −3.93, p < .0008.

Individual differences in reported disgust of mutilation or bodily products did not influence the amount of time that pictures of mutilation or contamination were viewed either overall, or in the last second of picture viewing, or at any interval. However, reported disgust of sexual activities was related to overall shorter gaze duration when viewing pictures of nude people, F(1,36) = 6, p = .02. Separate tests indicated that, for women, the relationship between reported disgust and gaze duration was significant when viewing either nude males, r = −.47, F(1,20) = 6, p = .02, or nude females, r = −.48, F(1,20) = 4.4, p = .05, with greater reported disgust of sexual activity associated with shorter gaze duration. For men, there was no relationship between reported disgust of sexual activity and gaze duration when viewing either nude females or males.

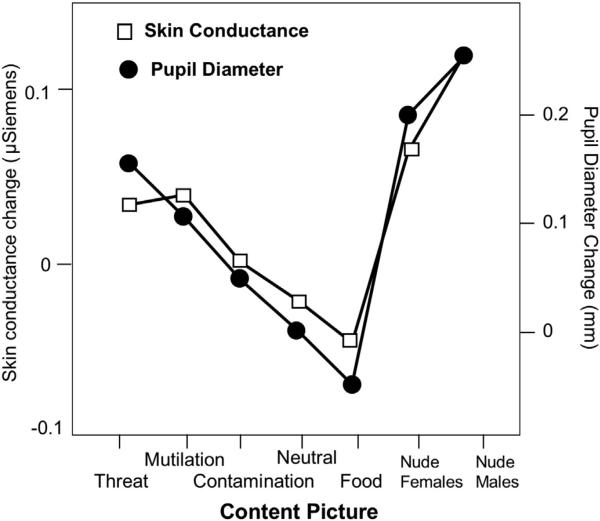

3.1. Skin conductance responses and pupil diameter

Fig. 2 illustrates the mean change in skin conductance level and pupil diameter as a function of hedonic content. These two measures clearly co-varied, and showed a similar pattern of modulation, with significant effects of content for both skin conductance, F(6,33) = 3.04, p = .018, and for pupil diameter, F(6, 32) = 32, p < .0001. There were no effects or interactions involving gender. Follow-up Bonferroni tests (t > 3.33, p < .001) indicated that, compared to pairs with two neutral scenes, pairs including pictures of mutilation, threat, and nude people showed significantly larger pupil dilation; for skin conductance, pairs including pictures of mutilation and nude people prompted significantly larger conductance changes than neutral scenes. Individual differences in reported disgust did not affect skin conductance changes or pupil diameter when viewing mutilation or contamination pictures. For pictures of nude males and females, a Gender × Reported Disgust interaction, F(1,34) = 5.2, p = .03 for skin conductance change indicated that women reporting higher disgust of sex responded with larger conductance changes when viewing pictures of either nude males or nude females, F(1,18) = 5.3, p = .03.

Fig. 2.

Skin conductance change and pupil diameter covary as a function of specific hedonic content.

4. Discussion

Sustained attention capture was measured by tracking the eye across time in a selective looking paradigm, with results indicating significant differences due to specific hedonic content, gender and disgust sensitivity. Initially, gaze duration was longer on pictures with affective content, compared to pairs that contained a neutral content picture (or to the neutral control picture in each pair), with a slight preference for viewing pleasant scenes in the earliest interval. By the last second of the viewing interval, however, scenes of contamination or nude males showed significant avoidance for both men and women, whereas scenes of mutilation did not prompt avoidance. Gender differences were most apparent for scenes including nude females, in which men showed sustained gaze across the viewing interval, whereas women showed no preference for sustained viewing of either nude males or females, and ultimately avoided looking at either content later in the viewing interval. Moreover, for women, gaze duration on nude scenes was inversely related to reported disgust of sexual activities. Taken together, choice viewing behavior is an unobtrusive additional index of sustained attention capture that is influenced by individual differences and preferences, as well as hedonic content.

Whereas some attentional bias studies have reported enhanced disruption of primary task performance immediately following presentation of disgusting stimuli, there was no evidence of enhanced early attention capture, measured by fixation duration, for pictures of contamination in the current study. Rather, consistent with theories predicting that disgust stems from a disease avoidance mechanism (e.g. Oaten et al., 2009), following initial attention capture, scenes of contamination were associated with significant avoidance by both men and women, irrespective of differences in reported disgust. Relatedly, using a larger (4 scene) visual array and a longer (30 s) viewing period, Armstrong et al. (2012) also found no differences in avoidance of contamination scenes for participants reporting high fear or low fear of contamination.

Although scenes of both mutilation and contamination are reliably reported as eliciting “disgust” (e.g., Bradley et al., 2001b; Libkuman et al., 2007), there was no evidence in the current study to support the prediction that pictures of mutilated bodies prompted an averted gaze at any time during the viewing interval, which was found for pictures depicting vomit, feces, and other non-bloody, but disgusting, scenes. Among the theories that have attempted to explain why people seek exposure to media depicting blood or mutilation are “arousal” theories (e.g., Zuckerman, 1996), which suggest that this material induces an “adrenalin rush” similar to extreme sports. Somewhat consistent with this, measures of sympathetic arousal when viewing mutilation scenes, including heightened skin conductance and pupil change, were reliably higher than for scenes of contamination.

Although individual differences in the willingness to look at blood and mutilation are commonly encountered in daily life, differences in reported disgust of blood and mutilation did not reliably modulate gaze duration in the current study. Because the incidence of blood phobia is relatively low in the general population, the lack of correlation in the current study may simply reflect the use of an unselected sample. On the other hand, only marginal differences have been obtained in free-viewing duration even in studies in which participants are specifically selected for blood or mutilation fear (Hamm et al., 1997; Buodo et al., 2006). Taken together, the data suggest that pictures of blood and mutilation are sympathetically arousing and capture sustained processing in both men and women.

One unexpected finding was a slight enhancement in initial fixation duration for pleasant, compared to unpleasant, scenes, regardless of whether pleasant scenes depicted appetizing food or nude people. A preference in processing pleasant scenes has not been found in other measures of early picture processing, such as event-related potentials, in which pictures of nude people typically prompt heightened potentials, compared to food scenes (e.g., Minnix et al., 2013). In the current study, viewing pictures of food did not elicit enhanced pupil diameter or skin conductance activity with both responses were significantly lower than those elicited when viewing scenes of nude people. If replicable, theses data suggest that eye movement behavior may be an additional measure of hedonic valence, as well as emotional arousal, at least in terms of early attention capture.

For erotic stimuli, choice viewing duration was clearly affected by gender. Men showed a clear preference for looking at pictures of nude females which remained remarkably stable across the viewing interval, whereas women never showed a preference for viewing opposite-, compared to same-sex nudes. Rather, for women, the pattern of choice viewing was almost identical for nude females as it was for nude males, with both showing significant avoidance in the final second of picture viewing. On the other hand, pairs that included nude people – either male or female – elicited the largest changes in skin conductance and pupil diameter for both men and women. These data are consistent with previous studies showing discordance between physiological engagement and ratings of subjective arousal for erotic stimuli (see Rupp and Wallen, 2008), and additionally indicate that this discordance is also found in choice gaze behavior when confronted with scenes of opposite- or same-sex nudes. Factors that have been considered in understanding gender differences in behavioral reactions to sexually explicit stimuli include social, cultural, religious, and biological variables (Rupp and Wallen, 2008). Abbreviated viewing of nude scenes by women in the current study was enhanced for those reporting disgust of sexually-related activities, lending some support to the influence of factors that can modulate voluntary behaviors (e.g. ratings, direction of gaze) that are not necessarily shared by all women.

4.1. Summary

Sustained attention capture was measured by eye movement behavior in a selective looking paradigm. When confronted with an emotionally engaging and a neutral picture, gaze duration to the affective member of the pair varied significantly with specific affective content, with heightened initial attention capture for all affective images followed by significant avoidance of scenes depicting contamination or nude males for both men and women. Scenes depicting nude females, on the other hand, prompted differences as a function of gender, with sustained processing found for men, and significant avoidance for women. Choice viewing in a selective looking paradigm is sensitive to differences in hedonic content as well as gender and individual preferences, making it an informative measure in studies of emotional behavior and individual differences.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by research grant MH072850 to Margaret M. Bradley. Thanks to Bob Sivinski for assistance with data collection and initial reduction. Correspondence concerning this manuscript can be sent to the Margaret M. Bradley at the Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, Box 112766, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, 32611.

The list of the subset of pictures used in this study from the IAPS (Lang et al., 2008) is available from the authors.

References

- Armstrong T, Sarawgi S, Olatunji BO. Attentional bias toward threat in contamination fear: overt components and behavioral correlates. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2012;2012(1):232–237. doi: 10.1037/a0024453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM. Natural selective attention: orienting and emotion. Psychophysiology. 2009;46:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00702.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Codispoti M, Cuthbert BN, Lang PJ. Emotion and motivation I: defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion. 2001a;1:276–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Codispoti M, Sabatinelli D, Lang PJ. Emotion and motivation II: sex differences in picture processing. Emotion. 2001b;1:300–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Miccoli L, Escrig MA, Lang PJ. The pupil as a measure of emotional arousal and autonomic activation. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:602–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00654.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buodo G, Sarlo M, Codispoti M, Palomba D. Event-related potentials and visual avoidance in blood phobics: is there any attentional bias? Depression Anxiety. 2006;23:304–311. doi: 10.1002/da.20172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.20172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo MG, Lang PJ. Gaze patterns when looking at emotional pictures: motivationally biased attention. Motiv. Emot. 2004;28:221–243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:MOEM.0000040153.26156.ed. [Google Scholar]

- Carretié L. Exogenous (automatic) attention to emotional stimuli: a review. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;14:1228–1258. doi: 10.3758/s13415-014-0270-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/s13415-014-0270-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretié L, Ruiz-Padial E, Lopez-Martin S, Albert J. Decomposing unpleasantness: differential exogenous attention to disgusting and fearful stimuli. Biol. Psychol. 2011;86:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers ML, Reiger G, Latty E, Bailey JM. A sex difference in the specificity of sexual arousal. Psychol. Sci. 2004;15:736–744. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers ML, Seto MC, Lalumiere ML, Laan E, Grimbos T. Agreement of self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal in men and women: a meta-analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010;39:5–56. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9556-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Olatunji BO, Lohr JM, Williams NL. Attentional bias differences between fear and disgust: implications for the role of disgust in disgust-related anxiety disorders. Cogn. Emot. 2009;23:675–687. doi: 10.1080/02699930802051599. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699930802051599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook III EW. VPM Reference Manual. Author; Birmingham, Alabama: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Costell RM, Lunde DT, Kopell BS, Wittner WK. Contingent negative variation as an indicator of sexual object pleasure. Science. 1972;177:718–720. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4050.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, McCauley CR, Rozin P. The Disgust Scale, Version 2, Short form from. 2002 http://www.people.virginia.edu~jdh6n/disgustscale.html.

- Hamm AO, Cuthbert BN, Globisch J, Vaitl D. Fear and the startle reflex: blink modulation and autonomic response patterns in animal and mutilation fearful subjects. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:97–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In-Albon T, Kossowsky J, Schneider S. Vigilance and avoidance of threat in the eye movements of children with separation anxiety disorder. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010;38:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9359-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson E, Carpenter D, Graham CA. Selecting films for sex research: gender differences in erotic film preference. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2003;32:243–251. doi: 10.1023/a:1023413617648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukounas E, McCabe M. Sexual and emotional variables influencing sexual response to erotica. Behav. Res. Ther. 1997;35:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS, Mesulam MM, Gitelman DR, Weintraub S. Emotional curiosity: modulation of visuospatial attention by arousal is preserved in aging and early-stage Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:1734–1740. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Greenwald MK, Bradley MM, Hamm AO. Looking at pictures: affective, facial, visceral, and behavioral reactions. Psychophysiology. 1993;30:261–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert MM. Motivated attention: affect, activation and action. In: Lang PJ, Simons RF, Balaban MT, editors. Attention and Orienting: Sensory and Motivational Processes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1997. pp. 97–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Technical Report A-7. University of Florida; Gainesville, FL.: 2008. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. [Google Scholar]

- Libkuman TM, Otani H, Kern R, Viger SG, Novak N. Multidimensional normative ratings for the International Affective Picture System. Behav. Res. Methods. 2007;39:326–334. doi: 10.3758/bf03193164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnix J, Versace F, Robinson JD, Lam CY, Engelmann JY, Cui Y, Brown VL, Cinciripini P. The late positive potential (LPP) in response to varying types of emotional and cigarette stimuli in smokers: a content comparison. Psychophysiology. 2013;89:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Stockton M. Gender and self-reported sexual arousal in response to sexual stimulation: a meta-analytic review. Sex Roles. 1997;37:135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Nummenmaa L, Hyönä J, Calvo MG. Eye movement assessment of selective attentional capture by emotional pictures. Emotion. 2006;6:257–268. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nummenmaa L, Hyönä J, Calvo MG. Emotional scene content drives the saccade generation system reflexively. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2009;35:305–323. doi: 10.1037/a0013626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oaten M, Stevenson RJ, Case TI. Disgust as a disease-avoidance mechanism. Psychol. Bull. 2009;133:303–321. doi: 10.1037/a0014823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinck M, Becker ES. Spider fearful individuals attend to threat, then quickly avoid it: evidence from eye movements. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2006;115:231–238. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rösler A, Ulrich C, Billino J, Sterzer P, Weidauer S, Bernhardt T, Kleinschmidt A. Effects of arousing emotional scenes on the distribution of visuospatial attention: changes with aging and early subcortical vascular dementia. J. Neurol. Sci. 2005;229–230:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Haidt J, McCauley CR. Disgust. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, editors. Handbook of Emotions. 2nd Edition Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 637–653. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp HA, Wallen K. Sex differences in response to visual sexual stimuli: a review. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2008;37:206–218. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman DL. A comparison of male and female patterns of sexual arousal. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1981;10:477–492. doi: 10.1007/BF01541588. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01541588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hooff JC, Devue C, Vieweg PE, Theeuwes J. Disgust- and not fear-evoking images hold our attention. Acta Psychol. 2013;143:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.02.001. T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking and the taste of vicarious horror. In: Weaver JB III, Tamborini R, editors. Horror Films: Current Research on Audience Preferences and Reactions. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]