Abstract

Background

ABO blood group has been associated with risk of cancers of the pancreas, stomach, ovary, kidney and skin, but has not been evaluated in relation to risk of aggressive prostate cancer.

Methods

We used three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (rs8176746, rs505922, and rs8176704) to determine ABO genotype in 2,774 aggressive prostate cancer cases and 4,443 controls from the Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3). Unconditional logistic regression was used to calculate age and study adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between blood type, genotype and risk of aggressive prostate cancer (Gleason score ≥8 or locally advanced/metastatic disease (stage T3/T4/N1/M1).

Results

We found no association between ABO blood type and risk of aggressive prostate cancer (Type A: OR=0.97, 95% CI=0.87-1.08; Type B: OR=0.92, 95% CI=0.77-1.09; Type AB: OR=1.25, 95% CI=0.98-1.59, compared to Type O, respectively). Similarly, there was no association between ‘dose’ of A or B alleles and aggressive prostate cancer risk.

Conclusions

ABO blood type was not associated with risk of aggressive prostate cancer.

Keywords: ABO, blood type, prostate cancer, genetic epidemiology

Introduction

Blood group can be traced to a single gene, ABO, located on chromosome 9q34. ABO encodes a glycosyltransferase that catalyzes the transfer of carbohydrates to red blood cells, thereby forming the distinct antigenic structures of the A and B blood groups. ABO blood group has been associated with several malignancies, including cancers of the pancreas(1), ovary(2), kidney(3), and skin(4). One study failed to show an association between ABO blood group and overall prostate cancer(5); however, no studies have focused on aggressive prostate cancer, which have been shown to be etiologically different from indolent cancer(6). We used genotype data to investigate the association between ABO blood type (A, B, AB, and O), as well as variation in ABO (OO, AO, AA, AB, BO, BB) and aggressive prostate cancer risk.

Material and Methods

Data were from the Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3) aggressive prostate cancer genome-wide association study (GWAS), described in detail elsewhere(7). Cases and controls were selected from prospective cohort studies, and were restricted to men of European ancestry. Cases were men with incident prostate cancer with high histologic grade (Gleason score ≥8) or locally advanced/metastatic disease (stage T3/T4/N1/M1); cases were followed for overall and cancer specific mortality. Controls were men without a diagnosis of prostate cancer. Assessment of ABO blood group alleles was conducted using genotype data from rs505922, rs8176704 and rs8176746 in ABO to infer phased haplotypes for each participant with >99% posterior probability, based on an expectation-maximization algorithm(8), similarly to prior studies (1,2). Briefly, rs8176746 is a marker of the B allele and rs505922 is a proxy (r2 =1) for rs687289, a marker of the O allele; rs8176704 distinguishes the A1 and A2 alleles(8). Unconditional logistic regression estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of the association between ABO blood group and aggressive prostate cancer adjusted for age and study. We further examined dose of A and B alleles by investigating the association between risk of aggressive prostate cancer and ABO genotype (AO, AA, BO, BB, AB, OO). We also examined study-specific associations between ABO blood group and aggressive prostate cancer. Among cases, we used Cox proportional hazards regression to assess the association between ABO blood group and prostate cancer-specific mortality, adjusted for age at diagnosis and study. P-values were 2-sided and analyses were done using SAS statistical packages (SAS Institute).

Results

The study included 2,774 aggressive prostate cancer cases and 4,443 controls. The frequency of ABO blood group is shown in Table 1 and for each cohort in Supplemental Table 1. When adjusted for age and study, there was no association between ABO blood types and risk of aggressive prostate cancer (Table 1). We found no association between Type A or AB, compared to Type O, and risk of aggressive disease. Similar results were observed when we evaluated ABO genotype (Supplemental Table 2). In the case-only analysis (n=2,774), there was no association between ABO blood group or genotype and prostate cancer-specific mortality (n=598 prostate cancer deaths) (data not shown).

Table 1. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the association between ABO blood type and aggressive prostate cancer1 risk, Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium.

| Type O | Type A | Type B | Type AB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) cases | 1172 (42%) | 1182 (43%) | 285 (10%) | 135 (5%) |

| N (%) controls | 1772 (40%) | 1928 (44%) | 534 (12%) | 209 (5%) |

| Multivariable adjusted OR (95% CI)2 | Ref. | 0.97 (0.87-1.08) | 0.92 (0.77-1.09) | 1.25 (0.98-1.59) |

Aggressive prostate cancer defined as Gleason 8+ or locally advanced/metastatic disease

Adjusted for age and study cohort

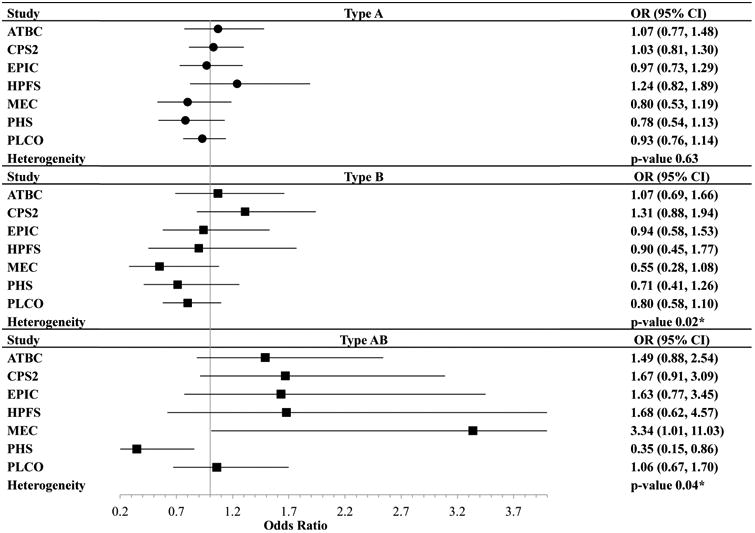

Figure 1 presents study-specific odds ratios for ABO blood group and risk of aggressive disease. There was heterogeneity across studies and no statistically significant associations comparing Type A or B to Type O in any individual study. There was a positive association with aggressive prostate cancer comparing Type AB to O in the Multiethnic Cohort (OR: 3.34, 95% CI: 1.01-11.03) and an inverse association in the Physicians'; Health Study (OR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.15-0.86).

Figure 1. Association between ABO blood type and aggressive prostate cancer risk by study, Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium.

*Heterogeneity across the cohort was assessed using p-value from Cochran's Q statistic

Discussion

In this large nested case-control study, we found no significant association between ABO blood group and aggressive prostate cancer risk or prostate cancer-specific mortality. These data are consistent with a prior study examining prostate cancer risk overall(5).

Previous studies have generally shown an increased risk of cancer, including pancreas, ovarian, and renal, for non-Type O blood group compared to Type O(1-3). The potential mechanisms linking ABO to risk of cancer are unclear. It has been suggested that ABO antigens interfere with intercellular adhesion and membrane signaling, and may be involved with angiogenesis(3). In addition, ABO blood group may affect the systemic inflammatory state and immune surveillance for malignant cells(1,3,4).

A strength of this study is the use of genotype-derived blood groups, which reduced the risk of exposure misclassification from self-report blood type and allowed us to specifically assess whether genotypic variation in ABO was associated with aggressive prostate cancer risk. Restricting to men of European ancestry may limit the generalizability of our findings to men of other ethnicities with differing prevalence of blood types and prostate cancer risk. Finally, despite a large overall study, the prevalence of type AB was low. Although there is some heterogeneity among studies, overall ABO blood type and ABO genotype do not appear to play a role in the development or progression of prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the participants of the BPC3 studies. The authors thank Dr. Philip Prorok, Division of Cancer Prevention, NCI; the screening center investigators and staff of the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial; Mr. Thomas Riley and staff at Information Management Services, Inc.; and Ms. Barbara O'Brien and staff at Westat, Inc. for their contributions to the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial. We thank Hongyan Huang for assistance in preparing the data.

Financial Support: The BPC3 is supported by the US National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute under cooperative agreements U01-CA98233 (PHS, HPFS), U01-CA98710 (CPS2), U01-CA98216 (EPIC), U01-CA98758, R01 CA63464, P01 CA33619, R37 CA54281 and UM1 CA164973 (MEC). PLCO and ATBC was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics and by contracts from the Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, NIH, DHHS. The Danish study Diet, Cancer and Health was funded by the Danish Cancer Society. The EPIC study of vitamin D and prostate cancer and the EPIC-UK cohorts were supported by funding from Cancer Research UK and Medical Research Council UK. EPIC-Greece was supported through the Hellenic Health Foundation. EPIC-Spain was supported by Health Research Fund (FIS); Regional Governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia (No. 6236) and Navarra; and ISCIII RETIC (RD06/0020) (Spain). EPIC-Italy was supported by the Sicilian government, Aire-Onlus Ragusa (Italy). MORGEN-EPIC was supported by the European Commission (DG-SANCO), the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), and Statistics Netherlands. I.M. Shui received a U.S. Army Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Post-doctoral Fellowship. L.A. Mucci and K.M. Wilson are Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigators. S.C. Markt is supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health Training Grant (T32 CA09001).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interests relating to this study.

References

- 1.Wolpin BM, Kraft P, Gross M, Helzlsouer K, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Steplowski E, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Arslan AA, Jacobs EJ, Lacroix A, Petersen G, Zheng W, Albanes D, Allen NE, Amundadottir L, Anderson G, Boutron-Ruault MC, Buring JE, Canzian F, Chanock SJ, Clipp S, Gaziano JM, Giovannucci EL, Hallmans G, Hankinson SE, Hoover RN, Hunter DJ, Hutchinson A, Jacobs K, Kooperberg C, Lynch SM, Mendelsohn JB, Michaud DS, Overvad K, Patel AV, Rajkovic A, Sanchez MJ, Shu XO, Slimani N, Thomas G, Tobias GS, Trichopoulos D, Vineis P, Virtamo J, Wactawski-Wende J, Yu K, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Hartge P, Fuchs CS. Pancreatic cancer risk and ABO blood group alleles: results from the pancreatic cancer cohort consortium. Cancer Res. 2010;70(3):1015–1023. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gates MA, Wolpin BM, Cramer DW, Hankinson SE, Tworoger SS. ABO blood group and incidence of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(2):482–486. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joh HK, Cho E, Choueiri TK. ABO blood group and risk of renal cell cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(6):528–532. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie J, Qureshi AA, Li Y, Han J. ABO blood group and incidence of skin cancer. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e11972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iodice S, Maisonneuve P, Botteri E, Sandri MT, Lowenfels AB. ABO blood group and cancer. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2010;46(18):3345–3350. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Platz EA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Risk factors for prostate cancer incidence and progression in the health professionals follow-up study. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(7):1571–1578. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schumacher FR, Berndt SI, Siddiq A, Jacobs KB, Wang Z, Lindstrom S, Stevens VL, Chen C, Mondul AM, Travis RC, Stram DO, Eeles RA, Easton DF, Giles G, Hopper JL, Neal DE, Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Muir K, Al Olama AA, Kote-Jarai Z, Guy M, Severi G, Gronberg H, Isaacs WB, Karlsson R, Wiklund F, Xu J, Allen NE, Andriole GL, Barricarte A, Boeing H, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Crawford ED, Diver WR, Gonzalez CA, Gaziano JM, Giovannucci EL, Johansson M, Le Marchand L, Ma J, Sieri S, Stattin P, Stampfer MJ, Tjonneland A, Vineis P, Virtamo J, Vogel U, Weinstein SJ, Yeager M, Thun MJ, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Albanes D, Hayes RB, Feigelson HS, Riboli E, Hunter DJ, Chanock SJ, Haiman CA, Kraft P. Genome-wide association study identifies new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Human molecular genetics. 2011;20(19):3867–3875. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraft P, Cox DG, Paynter RA, Hunter D, De Vivo I. Accounting for haplotype uncertainty in matched association studies: a comparison of simple and flexible techniques. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;28(3):261–272. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.