Abstract

The transcription factor Pax7 regulates skeletal muscle stem cell (satellite cells) specification and maintenance through various mechanisms, including repressing the activity of the muscle regulatory factor MyoD. Hence, Pax7-to-MyoD protein ratios can determine maintenance of the committed-undifferentiated state or activation of the differentiation program. Pax7 expression decreases sharply in differentiating myoblasts but is maintained in cells (re)acquiring quiescence, yet the mechanisms regulating Pax7 levels based on differentiation status are not well understood. Here we show that Pax7 levels are directly regulated by the ubiquitin-ligase Nedd4. Our results indicate that Nedd4 is expressed in quiescent and activated satellite cells, that Nedd4 and Pax7 physically interact during early muscle differentiation – correlating with Pax7 ubiquitination and decline – and that Nedd4 loss of function prevented this effect. Furthermore, even transient nuclear accumulation of Nedd4 induced a drop in Pax7 levels and precocious muscle differentiation. Consequently, we propose that Nedd4 functions as a novel Pax7 regulator, which activity is temporally and spatially controlled to modulate the Pax7 protein levels and therefore satellite cell fate.

Keywords: Pax7, Nedd4, satellite cells, skeletal muscle, proteasome, ubiquitin

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle features an astounding capacity for regeneration in response to acute injury or disease. This response depends on a discrete population of tissue-specific adult stem cells known as satellite cells (SCs) [1–4], which in normal conditions are maintained in a quiescent state and are located between the plasma membrane and the basal lamina of the host muscle fiber [5, 6]. Upon muscle damage SCs become activated, proliferate, migrate and induce the expression of muscle regulatory transcription factor (MRF) MyoD. At this stage, SCs are committed to the myogenic lineage and are referred to as adult myoblasts. Eventually, adult myoblasts become further committed to terminal differentiation by expression of the MRF myogenin, withdraw from the cell cycle, and either fuse with existing fibers or fuse one to another to form new myofibers [7]. The quiescent SC pool is replenished by self-renewal, ensuring subsequent muscle regeneration events [8].

Although the molecular regulation of muscle differentiation has been studied in detail, the mechanisms controlling SC maintenance and renewal remain to be elucidated. In this context, Pax7 expression is required for SC specification [9–11] and function [12, 13]. Through mechanisms not fully understood, Pax7 can repress MyoD transcriptional activity and terminal differentiation [14–17]. Accordingly, in the absence of Pax7 muscle progenitors undergo precocious differentiation in vivo [12, 13]. Interestingly, genetic and transcriptome studies indicate that Pax7 alone can initiate the myogenic program, inducing MyoD and/or Myf-5 expression [10, 18–22]. Together, these observations are consistent with a model where Pax7 can play dual roles in muscle progenitors [23]. Therefore, differential regulation of Pax7 protein may be critical for SC function, as the Pax7:MyoD protein ratio affects myogenic progression [16], while Pax7 rapidly declines upon myogenin induction [15, 16, 24, 25]. Consequently, identifying mechanisms involved in Pax7 decline in differentiating cells and Pax7 retention in self-renewing SCs is expected to have profound implications for the understanding of SC biology.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) mediates intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, with extreme substrate specificity and is therefore crucial for a variety of cellular processes during homeostasis and disease [26].

The UPS directs the covalent attachment of the 76aa protein ubiquitin to lysine residues of substrate proteins, targeting them for degradation by the 26S proteasome [27]. Ubiquitin transfer occurs in a sequential, ATP-dependent reaction involving three different enzymes: E1 activating, E2 conjugating and E3 ligase, which catalyzes ubiquitination of specific targets [28].

Nedd4 (neural precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated gene 4) is a member of the HECT (homologous to E6-AP carboxyl terminus) class of E3 ligases [29]. They directly interact with substrate proteins through conserved WW domains and transfer ubiquitin from E2 via their HECT catalytic domain [30]. Nedd4 regulates membrane, cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins in a variety of cell contexts [31], including skeletal muscle tissue [32–34]. Whereas Notch1 is the only Nedd4 muscle substrate reported to date [33], Nedd4 expression and function in SC remain to be determined.

Here we provide evidence indicating for the first time that Nedd4 can regulate muscle progenitor fate thought a mechanism involving control of Pax7 levels via the UPS, during early muscle differentiation.

RESULTS

Spatial and temporal regulation of Pax7 levels in muscle progenitors

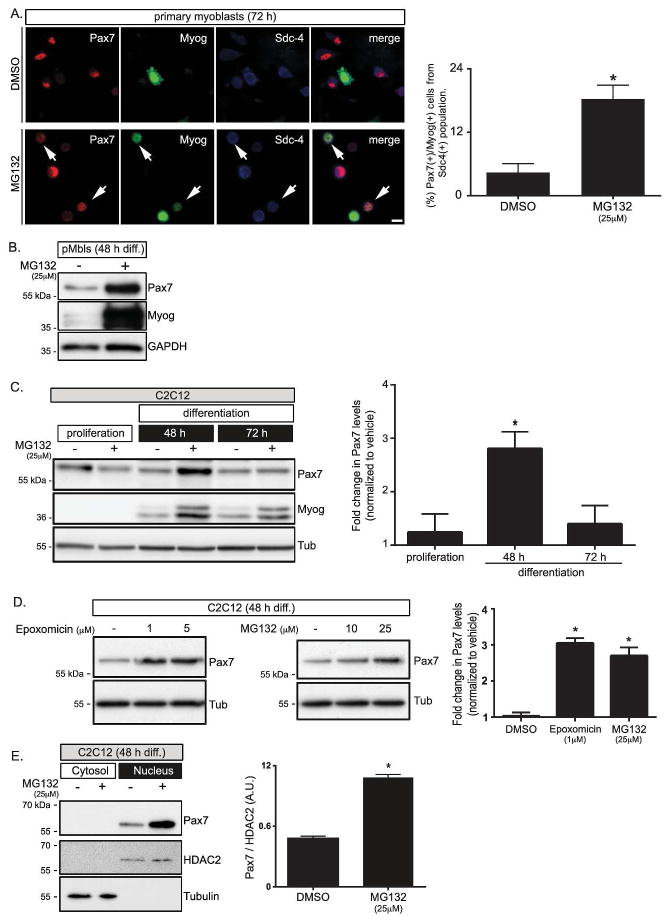

Pax7 decreases significantly parallel to the induction of myogenin expression in myoblasts cell lines; a process that was partially prevented by proteasome inhibition [16, 24]. Therefore, we asked whether Pax7 levels are regulated in a similar manner in activated SCs. For this, adult mouse primary myoblasts were allowed to differentiate in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. As expected, Pax7 and myogenin exhibited a mutually exclusive expression pattern in vehicle-treated cells, as observed by indirect immunofluorescence (IF) (Fig. 1A). However, MG132 treated cultures showed a significant increase (≥4 fold) in the percentage of Pax7(+)/myogenin(+) cells (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, Western blotting analyses revealed that Pax7 protein levels increased ≥ 2.5 fold upon MG132 treatment (Fig. 1B). To further confirm the specificity of these observations, we compared the effects of two non-related proteasome inhibitors -MG132 and epoxomicin- on Pax7 expression. As shown in Figure 1 (C–D), treatment with either inhibitor resulted in a dose-dependent increase of Pax7 protein in differentiating C2C12 myoblasts. Interestingly, this effect was consistently observed within a discrete window of time (~48 h after differentiation induction, Fig. 1C). No changes in Pax7 levels were detected in cells maintained in proliferation conditions (Fig. 1C) or in cells analyzed later during differentiation (Fig. 1C), where any remaining Pax7 expression is largely confined to the “reserve population” of undifferentiated cells [15]. On the other hand, Pax7 protein was detected only in nuclear fractions in both control and MG132 treated cells (Fig. 1E), indicating that regulation of Pax7 levels occurs within this cellular compartment.

FIGURE 1. Pax7 stability is regulated by the proteasome during myogenesis.

A, Proteasome inhibition results in myogenin (Myog) and Pax7 co-expression (arrows) in adult mouse primary myoblasts (pMbs). Syndecan-4 (Sdc-4) expression was used as lineage marker. Scale bar: 10 μm. Right panel: quantification (three separate experiments; (mean ± s.e.m.)) of percentage of Myog(+)/Pax7(+) cells from the total Sdc-4(+) population; Student’s t test *p<0.005.

B, Western Blot analysis of Pax7 and myogenin expression in 48 h cultured pMbs treated as in A.

C, Pax7 levels are significantly increased upon proteasome inhibition during differentiation commitment in C2C12 myoblasts. Myogenin (Myog): differentiation marker, tubulin (Tub): loading control. Right panel: quantification of Pax7 fold change (mean ± s.e.m.) of three separate experiments. One way ANOVA *p<0.005.

D, Epoxomicin mediated proteasome inhibition recapitulates Pax7 accumulation in differentiating C2C12 myoblasts. MG132 effect is shown as positive control. Right panel: quantification of Pax7 fold change (mean ± s.e.m.) of three separate experiments for 1μM epoxomicin and 25 μM MG132 treatments. One way ANOVA *p<0.005.

E, Proteasome inhibition results in Pax7 nuclear accumulation. Pax7 expression was determined by Western blot in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions: (tubulin: cytoplasmic marker; histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2): nuclear marker), Right panel: quantification of Pax7 protein levels normalized to HDAC2 (mean ± s.e.m.) of three separate experiments. Student’s t test *p<0.005. MG132 was used at 25μM in B,C and E.

Pax7 is ubiquitinated in differentiating myogenic cells

In an attempt to understand the mechanism(s) involved in Pax7 control, we used Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) coupled to mass spectrometry to identify direct Pax7 regulators (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MuDPIT) and in vitro pull-down assays revealed several candidates Pax7-binding proteins, including members of the UPS (Fig. S1B). Based on our previous results, we focused on the analysis of these particular candidates in the post-translational control of Pax7.

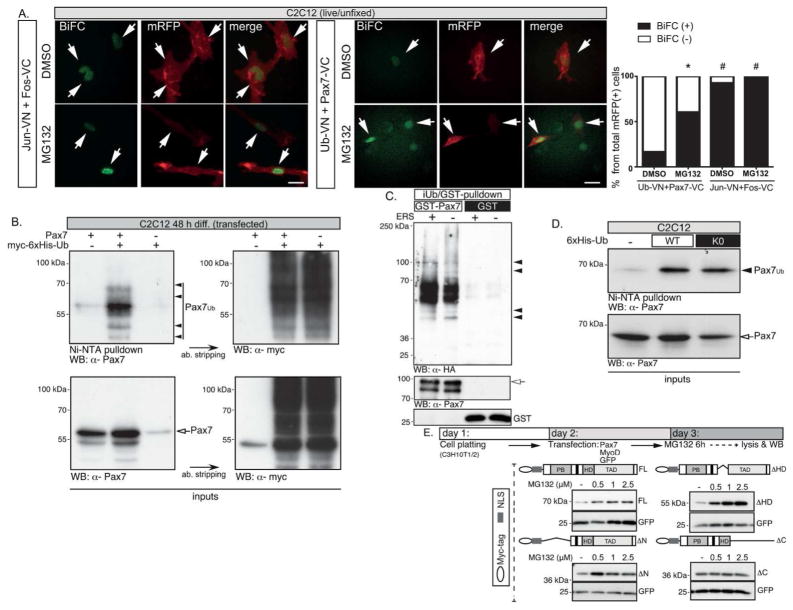

First we verified in vivo Pax7 ubiquitination in C2C12 cells by bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays (BiFC; see Materials and Methods) [35]. Live-cell fluorescent signal was only reconstituted when Pax7-[Venus C-terminus] fusion protein (Pax7-VC) and ubiquitin-[Venus N-terminus] fusion protein (ubiquitin-VN) were co-expressed (Fig. 2A; Fig. S2). Importantly, complementation was detected in the cell nucleus and enhanced by MG132 treatment, correlating with increased Pax7-VC levels (Fig. S1A). Control complementation mediated by interacting proteins bFos-VC and bJun-VN remained unaffected by the presence of MG132 (Fig. 2A), as previously described [35]. Ubiquitin-Pax7 complexes were also detected by denaturating Ni-NTA affinity purification of total ubiquitinated proteins from C2C12 myoblasts expressing myc-6xHis-Ub (Fig. 2B), suggesting that Pax7 is indeed ubiquitinated. Unexpectedly however, ubiquitin-Pax7 appeared mainly as discrete band(s) instead of the smear-like signal characteristic of poly-ubiquitinated proteins targeted to the proteasome (Fig. 2B, compare Ni-NTA pulldown vs. input). Furthermore, equivalent ubiquitin-Pax7 complexes were obtained in vitro upon incubation of GST-Pax7 fusion protein with a UPS-enriched HeLa cell extract plus ATP (Fig. 2C). In this scenario, we considered two alternative explanations: i) Pax7 was modified by addition of single ubiquitin molecule(s) (i.e. mono-ubiquitination or multi-mono-ubiquitination) or ii) Pax7 co-purificate indirectly due to its interaction with ubiquitinated proteins. The later argument seemed less likely due to the denaturating conditions used during Ni-NTA affinity purification and since equivalent ubiquitin-Pax7 species were obtained in vivo and in vitro. In order to test the remaining possibility, in vivo ubiquitination assays were performed in C2C12 cells transfected with either 6xHis-ubiquitin (wt) or 6xHis-ubiquitin proteins lacking all lysines (K0), preventing polyubiquitin chain formation while still allowing ubiquitin conjugation to the target protein [36–38]. Ubiquitin-Pax7 complexes with equivalent relative molecular masses were detected in both conditions after Ni-NTA pulldown (see Materials and Methods) of ubiquitinated proteins, followed by Western blot for Pax7 (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2. Pax7 is ubiquitinated during myoblast differentiation.

A, Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) shows Pax7 ubiquitination in living cells. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with the indicated constructs and treated with MG132 10μM, 6 h prior to live-cell imaging. Arrows indicate positive BiFC. Right panel: quantification (three separate experiments) of BiFC positive cells from total mRFP positive population. For Pax7-VC/Ub-VN complementation, this analysis shows 16,8 ± 8,4 % BiFC positive cells in the DMSO condition and 60,3 ± 5,2 % in the MG132 condition. Positive control bFos-VC–bJun-VN complementation shows 92,3 ± 3,8% and 98,1± 1,9% for DMSO and MG132 treatment respectively. One way ANOVA *p<0.005; # no significant difference.

B, Pax7 is ubiquitinated during myoblast differentiation. C2C12 cells were transfected with Pax7 and myc-6xHis-ubiquitin, induced to differentiate for 48 h and treated with MG132 10 μM 6 h prior to cell lysis. Denaturing Ni-NTA pulldown, followed by Western blot shows ubiquitinated Pax7 (arrowheads). Putative non-ubiquitinated Pax7 binding to Ni-NTA resin is indicated by white arrow.

C, Pax7 is ubiquitinated in vitro (iUb). Purified GST-Pax7 or GST-only proteins were incubated with S-100 HeLa cell-extracts plus or minus energy-supply (ERS), followed by GST pull-down and Western blot for HA-tag. Arrowhead indicates ubiquitinated Pax7 species and arrow indicated GST-Pax7.

D, Pax7 can be monoubiquitinated during myogenic differentiation. C2C12 cells were transfected with wild type (wt) or mutant (K0) 6xHis-ubiquitin. Denaturing Ni-NTA pulldown followed by Western blot for Pax7 show equivalent monoubiquitinated Pax7 species in both conditions (arrowhead).

E, Pax7 C-terminus is important for Pax7 proteasomal regulation. Upper panel: Experimental strategy. Lower panel: FL, ΔN and ΔHD Pax7 but not ΔC Pax7 levels are increased upon proteasome inhibition in differentiating (24 h) MyoD-converted C3H10T1/2 cells. GFP: transfection/loading control.

Together, these results support the concept that the UPS regulates Pax7 protein levels in differentiating myogenic cells. In this context, we have previously observed that deletion of Pax7 C-terminus domain (Pax7-ΔC) results in significantly higher expression when compared to the full-length Pax7 protein (Olguín et al., 2007). Accordingly, incubation with MG132 results in Pax7, ΔN and ΔHD Pax7-deletion-mutant accumulation when ectopically expressed in C3H10T1/2 cells. This accumulation is not observed for Pax7-ΔC (Fig. 2E), suggesting that Pax7 C-terminus domain is required (directly or indirectly) for Pax7 UPS-mediated regulation.

Ubiquitin ligase Nedd4 is a novel regulator of Pax7 stability in muscle progenitors

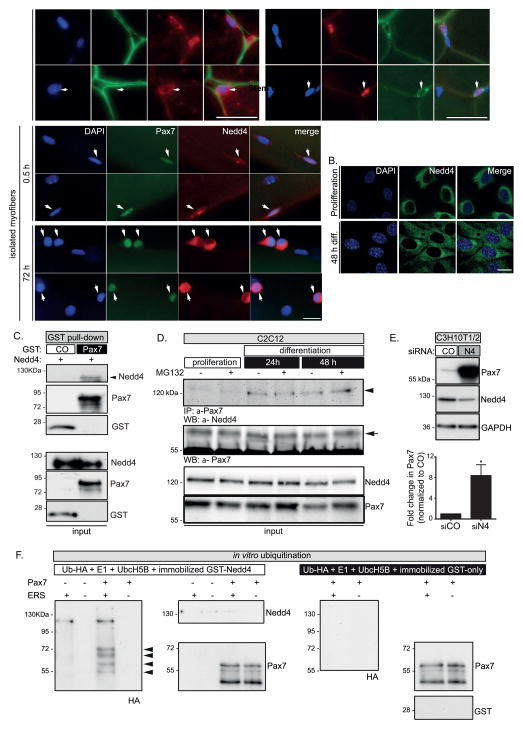

Among the candidate Pax7 regulators uncovered in our proteomics analysis we identified Nedd4 (Fig. S1B), a member of the HECT superfamily of E3 ligases [31], whose role in adult muscle progenitors had not been described. Therefore, we first examined its expression in quiescent and activated SCs. Nedd4 protein was detected in a subset of cells located underneath the basal lamina from tibialis anterior muscle sections (Fig. 3A). The identity of these cells was further confirmed by co-localization with the SC marker Pax7 (Fig. 3A). Although there was almost complete Pax7 and Nedd4 co-expression, Nedd4 was also expressed in Pax7(−) interstitial cells (Fig. 3A). This is not unexpected, since Nedd4 has been described in a variety of cell types.

FIGURE 3. Nedd4 interacts with and regulates Pax7 stability in muscle precursors.

A, Upper panels: Indirect IF for laminin (LN) or Pax7 staining and Nedd4 in adult mouse TA cross-sections, show that Nedd4 is expressed in cells located in a SC position (arrows). Asterisk indicates that interstitial cells may also express Nedd4. Scale bar: 100 μm. Lower panels: Nedd4 is expressed in myofiber-associated SCs (arrows) fixed immediately upon isolation (0.5 h) or after 72 h in culture. 100% of 0.5 h (n=17) and 100% of 72 h (n=123) cultured SCs are Nedd4 positive. Scale bar: 10μm.

B, Nedd4 is expressed during differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts. Indirect immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy show that Nedd4 is expressed at similar levels in proliferating or differentiating C2C12 myoblasts. Scale bar: 10 μm.

C–D, Nedd4 physically interacts with Pax7 during C2C12 myoblast differentiation, as detected via in vitro GST pull-down utilizing purified GST-Pax7 and Nedd4 (C, arrowhead) or co-immunoprecipitation (D, arrowhead). Note that in D, Pax7-Nedd4 interaction occurred preferentially in differentiating cells (24–48 h).

E, Nedd4 negatively regulates Pax7 levels. MyoD-converted C3H10T1/2 were co-transfected with Pax7 plus Nedd4 siRNA (or control) and induced to differentiate for 48 h. Nedd4 knockdown results in a significant increase of Pax7 levels in transfected cells. Lower panel: quantification of Pax7 fold change (mean ± s.e.m.) after Nedd4 siRNA treatment. Student’s t test *p<0.005.

F, Nedd4 ubiquitinates Pax7 in vitro. Purified Pax7 was incubated with E1, UbcH5B, HA-ubiquitin and energy supply with or without immobilized GST-Nedd4 protein. Ubiquitinated Pax7 was generated only in presence of Nedd4 (arrowheads) and energy supply. Controls for Nedd4, Pax7 and GST present in the supernatants are shown.

We also examined Nedd4 expression during ex-vivo SC activation and proliferation in isolated myofibers cultures (Fig. 3A, lower panels). Interestingly, Nedd4 exhibited a marked cytoplasmic expression pattern both in quiescent and activated SCs. This subcellular distribution was also observed in differentiating C2C12 myoblasts (Fig. 3B).

Next, we investigated the nature of the interaction between Pax7 and Nedd4 by in vitro GST pull-down and Western blotting. Nedd4 was significantly enriched when using GST-Pax7 as bait, while no interaction with GST was observed (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained performing pull-down using in vitro translated [35S]-Nedd4 (Fig. S1B), indicating that Pax7 and Nedd4 can physically interact. This interaction also appears to occur in vivo, since both proteins were co-IP from C2C12 myoblasts whole-cell extracts (Fig. 3D). Notably, co-IP was observed upon induction of differentiation (Fig. 3D) but not in cells maintained in proliferating conditions, consistent with our previous observations (see Fig. 1).

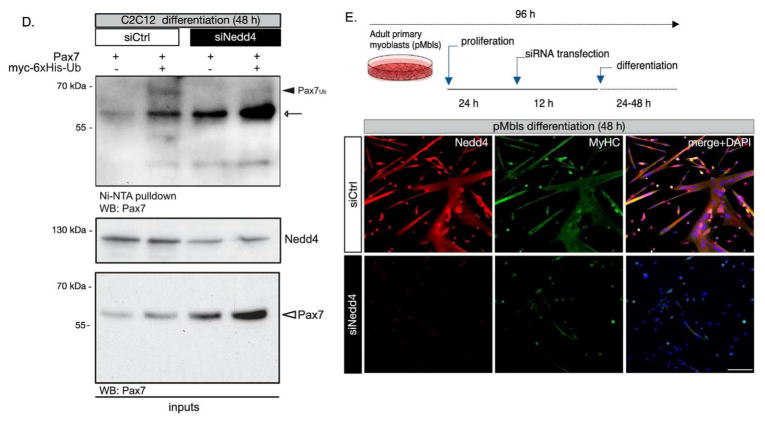

Since Nedd4 regulates the stability of several ligand proteins [31], we hypothesized that Nedd4 knockdown would result in increased Pax7 protein levels. We tested this idea using the C3H10T1/2 myogenic conversion model, since these cells express endogenous Nedd4 but not Pax7, thus allowing co-transfection of Pax7 cDNA and Nedd4 siRNA in order to evaluate the effect on Pax7 levels by Western blotting. Accordingly, Nedd4 knockdown (~52%) results in a >8 fold increase in Pax7 protein, while no significant changes were observed upon co-expression of a non-targeting siRNA (Fig. 3E). Next, we asked if Nedd4 could directly ubiquitinate Pax7 in vitro, using immobilized GST-Nedd4 fusion protein (see Materials and Methods). Under these conditions, we detected ubiquitinated Pax7 species that were absent when either Pax7 or ATP was omitted from the reaction (Fig. 3F). Importantly, these products do not correspond to immobilized Nedd4 or unmodified Pax7 (Fig. 3F), since no products were detected when Nedd4 was replaced in the reaction by immobilized GST-only protein (Fig. 3F).

Taken together, these observations indicate that i) Nedd4 and Pax7 are co-expressed and physically interact in adult myoblasts, and ii) Nedd4 can directly modify Pax7 protein.

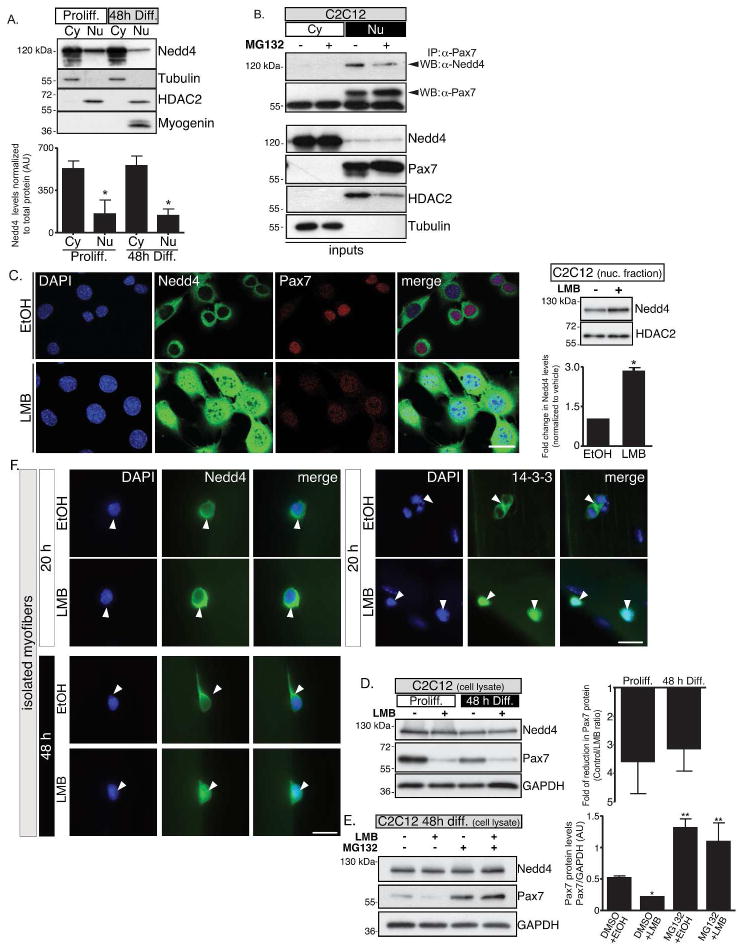

Nedd4 nuclear import/export is critical for regulation of Pax7 protein

Previous studies showed that Nedd4 possesses functional nuclear localization and nuclear export signals [39]. The latter appears to be particularly strong, limiting Nedd4 presence in the nucleus to almost undetectable levels. This effect can be prevented by inhibiting CRM1 (chromosome region maintenance 1)/exportin 1-dependent export [40], which results in nuclear accumulation of Nedd4 in HeLa cells [39]. Therefore, we decided to determine if nuclear translocation of Nedd4 would allow interaction with Pax7 in myogenic cells. For this, co-IP experiments were performed in isolated cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of C2C12 myoblasts. As described previously, Pax7 protein was only detectable in the nuclear compartment (Fig. 1D). Although highly enriched in cytoplasmic fractions, lower levels of Nedd4 (26 ± 10%) were detected in C2C12 nuclear extracts (Fig. 4A). Remarkably however, Nedd4 was efficiently co-IP from nuclear fractions using an anti-Pax7 antibody (Fig. 4B), suggesting that at least some Nedd4 protein was imported to the nucleus, allowing its interaction with Pax7. To further test this idea, C2C12 cells were treated with the CRM1 inhibitor leptomycin B (LMB). In line with previous reports, LMB resulted in a significant increase in Nedd4 in myoblast nuclei, as determined by confocal microscopy and Western blotting (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, nuclear accumulation of Nedd4 correlated with a significant decrease in the Pax7 signal (Fig. 4C), which was further confirmed by Western blotting (≥50% decrease compared to vehicle, Fig. 4D). Importantly, Pax7 decrease upon LMB treatment was efficiently prevented by proteasome inhibition (Fig. 4E), indicating that LMB-induced changes in Pax7 levels require active proteasome. In this context, we evaluated if Nedd4 nuclear import was differentially controlled in activated SCs. For this, single myofibers-associated SCs were treated with LMB (6 h) starting at 12 or 42 h after isolation. Surprisingly, at early time points Nedd4 localization was similar between vehicle and LMB treated cells. However, Nedd4 was efficiently accumulated in SC nuclei at 48 h post isolation (Fig. 4F). In order to distinguish between a general down regulation of the nuclear-cytoplasmic transport and a specific Nedd4 regulation, we determined the effect of LMB on the localization of the 14-3-3-protein family, which are known to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Fig. S3A). Interestingly, 14-3-3 proteins readily accumulate in SC nuclei treated with LMB at 12–20 h post isolation (Fig. 4F). Altogether, these results suggest that Nedd4 does not shuttle to the nuclear compartment constitutively, but most likely in response to myogenic stimuli.

FIGURE 4. Nedd4 localization is critical for the control of Pax7 stability.

A, Nedd4 is preferentially located to cytoplasm in C2C12 cells. Proliferating and differentiating C2C12 cells were subjected to subcellular fractioning and Nedd4 levels were analyzed by Western blotting.. Lower panel: quantification of Nedd4 protein normalized to total cytoplasmic or nuclear protein, respectively (mean ± s.e.m.). One way ANOVA *p<0.005.

B, Nedd4 interacts with Pax7 at the cell nucleus; indicated by IP analysis from isolated subcellular fractions.

C, Inhibition of CRM-1/exporting-1 (leptomycin B, LMB) in C2C12 myoblasts, results in nuclear Nedd4 accumulation when compared with vehicle treated cells (EtOH); analyzed by confocal microscopy (Left panel) and Western blotting (Right panel mean ± s.e.m. of Pax7 fold change. Student’s t test *p<0.005). Scale bar: 10 μm.

D, LMB treatment results in a reduction of Pax7 levels in C2C12 myoblasts. Right panel: Fold reduction of Pax7 levels in response to LMB treatment in proliferating and differentiating C2C12 cells (mean ± s.e.m.).

E, LMB induced Pax7 decline is dependent of proteasome activity. 48 h differentiating C2C12 cells were treated as indicated and analyzed via Western blotting (Right panel mean ± s.e.m. of Pax7 protein levels. One way ANOVA *p<0.005).

F, Nedd4 nuclear import is temporally regulated in activated SCs. Single fiber-associated SCs were treated with LMB for 6 h at 12–42 h post isolation (i.e. 20–48 h total in vitro culture time, respectively). Arrowheads indicate Nedd4 and 14-3-3 localization by IF. Scale bar: 10 μm.

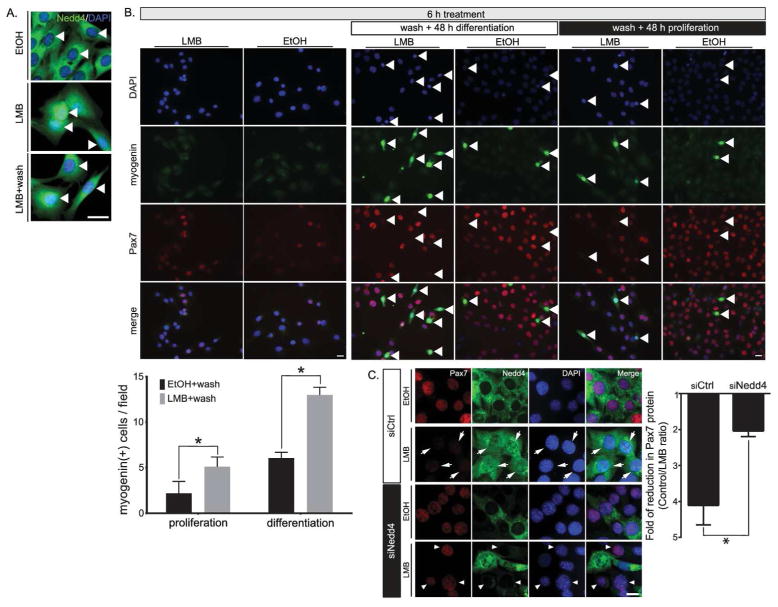

We have previously proposed that regulation of the Pax7:MRFs ratio is critical to maintain muscle progenitors in a self-renewing/proliferating state (Pax7high/MRFlow) or to allow activation of the differentiation program (Pax7low/MRFhigh). In this context, we hypothesized that a decrease in Pax7 levels upon LMB treatment would result in precocious differentiation induction. To test this possibility, LMB was removed after a 6 h treatment, and the cells were maintained in culture for an additional 48 h prior to fixation. Under these conditions, LMB-induced nuclear accumulation of Nedd4 was effectively reversed upon removal, as determined by loss of Nedd4 nuclear signal observed by IF (Fig. 5A). Nevertheless, Pax7 levels remained below control after transient LMB treatment (Fig. 5B), which correlated with a >2 fold increase in the percentage of myogenin (+) cells (Fig. 5B) and an increase in the population of cells expressing myosin heavy chain (Fig. S4), indicating progression towards terminal differentiation. A significant increase in myogenin (+) cells was also observed in LMB-treated cells maintained in proliferating culture conditions, suggesting that a transient decrease in Pax7 protein levels is sufficient to allow differentiation induction. Since Nedd4 is one of many proteins exported by a CRM1/exportin-1 dependent mechanism (Fig. S3A), we confirmed the specific requirement for Nedd4 by evaluating the effect of LMB on cells previously transfected with a Nedd4 siRNA or a non-targeting control siRNA: Nedd4 knockdown blocked the LMB-induced drop in Pax7 levels by at least 50% (Fig. 5C). Accordingly, we observed a decrease in ubiquitinated Pax7 species detected in C2C12 whole-cell extracts co-trasfected with 6xHis-ubiquitin and Nedd4 siRNA, followed by Ni-NTA pulldown and Pax7 Western blot (Fig. 5D). Further supporting a critical role for Nedd4 regulation during muscle differentiation in activated SCs, we observed a marked decrease in cell fusion and myosin heavy chain expression upon Nedd4 knockdown in adult primary myoblasts (Fig. 5E).

FIGURE 5. Nedd4 nuclear accumulation results in precocious muscle differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts.

A, LMB wash promotes Nedd4 cytoplasmic relocalization (arrowheads). C2C12 cells were treated for 6 h with LMB or vehicle (EtOH) prior to fixation or washed and cultured for additional 48 h prior to indirect immunofluorescence analysis. Scale bar: 10 μm.

B, Transient LMB treatment results in precocious myoblast differentiation. Cells were treated with LMB or vehicle (EtOH) for 6 h and either fixed immediately or washed and maintained in culture for 48 h (growth or differentiation conditions, as schematized) prior to fixation. LMB treatment resulted in a significant increase of myogenin positive cells in both conditions. Lower panel: quantification of myogenin positive cells per field (mean ± s.e.m.). One way ANOVA *p<0.005.

C, LMB mediated Pax7 protein reduction is dependent on Nedd4. Left panel: C2C12 cells were transfected with control (Ctrl) or Nedd4 siRNA and treated with vehicle or LMB 6 h prior to cell fixation. As expected, LMB treatment resulted in a Nedd4 nuclear accumulation concomitant to a decrease Pax7 protein levels (arrows). This phenotype is reversed by Nedd4 knock down (arrowheads). Right panel: Fold of reduction in Pax7 protein levels (mean ± s.e.m.) is significantly reduced by siNedd4 transfection. Student’s t test *p<0.005.

D, Nedd4 knockdown during C2C12 early differentiation, results in decreased Pax7 ubiquitination. C2C12 myoblasts were co-transfected with either control (siCtrl) or Nedd4 specific (siNedd4) siRNAs and myc-6xHis-ubiquitin, and induced to differentiate for 48 h prior to Ni-NTA pulldown followed by Pax7 Western blot. Black arrowhead indicates ubiquitin-Pax7 species (Pax7ub). White arrow indicates putative non-ubiquitinated Pax7 in Ni-NTA eluates. Nedd4 Western blot is shown as control for knockdown efficiency (~ 50%). Note that control for Pax7 expression (white arrowhead) correlates in size and relative signal levels of putative non-ubiquitinated Pax7 binding to Ni-NTA resin (white arrow).

E, Nedd4 knockdown impairs terminal muscle differentiation in activated SCs. Adult primary myoblasts were isolated and transfected with siCtrl or siNedd4 prior to differentiation induction. After 48 h, cells where fixed and tested for myotube formation and myosin heavy chain and Nedd4 expression by IF. Quantification of n=3 experiments indicate a ≥50% reduction in the fusion index (not shown), considering ≥3 nucleated cells as myotubes. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Together, these results suggest that regulation of Nedd4 sub-cellular localization is critical to modulate Pax7 protein levels by the UPS and therefore, muscle progenitor fate.

DISCUSSION

Adult muscle progenitor fate is influenced by a functional interaction between the transcription factor Pax7 and members of the MyoD family of MRFs. We have proposed that changes in the Pax7:MyoD protein ratio may act as a molecular rheostat fine-tuning acquisition of lineage identity while preventing precocious terminal differentiation [23]. In this scenario, post-translational modifications can play an important role controlling Pax7 expression and function in a context dependent manner [24, 41, 42]. In the present study we describe a novel mechanism by which the E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4 connects the UPS and the regulation of Pax7 levels in cells initiating muscle differentiation.

Nedd4 deletion leads to lethality before birth [43–45]. Interestingly, skeletal muscle and neuromuscular junction development in Nedd4-null mice are impaired, indicating a possible role for Nedd4 in muscle formation during embryogenesis [43–45]. In adult skeletal muscle, Nedd4 expression increases upon both denervation and unloading-induced atrophy, while muscle-specific Nedd4 knockout mice retain muscle mass after denervation [33, 34]; suggesting that Nedd4 directly participates in the generation of atrophic under very specific conditions, which in turn implies that different pathways in the muscle cell can lead to atrophy. Despite these findings, potential Nedd4 function(s) in muscle maintenance and repair have not been described. Our results show for the first time that i) Nedd4 is expressed in quiescent and activated SCs and ii) that Nedd4 regulates adult muscle progenitor cell fate by affecting Pax7 levels.

Pax7 levels are controlled by proteasomal activity

Proteasome inhibition partially recovered Pax7 expression in myogenin(+) cells, suggesting for the first time that Pax7 levels were post-translationaly regulated [16]. Here we showed that proteasome inhibition in primary adult myoblasts also leads to Pax7 retention in myogenin(+) cells (Fig. 1), strongly suggesting that proteasome-dependent degradation of Pax7 is a physiologically relevant mechanism to control the Pax7:MRFs balance. Interestingly, the timing of Pax7 decline is under temporal control, since Pax7 accumulation upon proteasome inhibition was restricted to early differentiation (Fig. 1).

Pax3 -a close Pax7 homolog- is also subject to UPS regulation [46]. In their study, Boutet and colleagues not only show that Pax3 is marked for degradation via a non-canonical pathway but also ruled out a similar regulation for Pax7. This conclusion is based on two observations: i) when Pax3 dropped, Pax7 levels were unaffected and ii) site-directed mutagenesis introducing a lysine in position 475 -key for Pax3 degradation- turned Pax7 susceptible to UPS-mediated degradation. The apparent contradiction with the results presented here may highlight key functional differences between the two Pax proteins. First, in the referenced study, Pax3 levels increased upon proteasome inhibition in proliferating myoblasts while Pax7 remained unchanged. As shown in Fig. 1C, Pax7 levels also remain unaffected by MG132 treatment in myoblasts maintained in proliferating culture conditions. Nevertheless, Pax7 levels are clearly affected by proteasome inhibition in differentiating myoblasts. Upon myogenic progression, Pax7 expression is maintained in a small population of undifferentiated “reserve cells” [47]. Interestingly, proteasome inhibition in differentiated cell cultures has no effect on the remaining Pax7 levels, supporting the idea that the UPS regulates Pax7 in a cell context-dependent manner. Differences in the nature and regulation of the signaling pathways involved in Pax3 and Pax7 degradation can also explain these disparities.

Pax7 mono-ubiquitination as signal for proteasomal degradation?

Using at least three different approaches (i.e. BiFC, immunoprecipitation and in vitro ubiquitination), we determined that Pax7 is ubiquitinated during muscle differentiation. Interestingly, Pax7 appears to be mono-ubiquitinated (Fig. 2B–E) in muscle progenitors as shown previously for Pax3 [46]. Importantly, we showed that E3 ligase Nedd4 catalyzed Pax7 mono-ubiquitination in vitro (Fig. 3F). Despite of this, in the present study we were unable to identify the specific Pax7-residue(s) involved. Nevertheless, studies using deletion mutants suggest that Pax7 carboxy terminus might be directly or indirectly involved in this process (Fig. 2F). Thus, it will be interesting to study the functional relevance of Pax7 mono-ubiquitination in its activity and degradation.

Ubiquitinated protein recognition by the proteasome is classically attributed to the presence of polyubiquitin chains [38], which are specifically recognized by the ubiquitin receptor subunits of proteasome complex Rpn10/S5a and Rpn13/ARM1 [48, 49]. However, non-canonical ubiquitin signals have also been described [50–53]. In this context, an increasing number of examples support the role of mono-ubiquitin modification as a bona fide signal for protein degradation [46, 54, 55]. Targeting mono-ubiquitinated proteins for degradation involves ubiquitin receptors carrying modified substrates to the proteasome [46, 51]. In this context, remains to be determined if Pax7 UPS-dependent regulation involves a similar mechanism.

Regulation of Nedd4 function in adult muscle precursors

Here we show that Nedd4 E3 ligase interacts with and regulates Pax7 protein levels in muscle precursors (Fig. 3). Nedd4 interaction with its substrates requires ubiquitin interacting motifs and the presence of ubiquitin binding domains in target proteins subjected to mono-ubiquitination [56, 57]. Additionally, Nedd4 catalytic activity is regulated in cis via intramolecular interaction of the C2 and HECT domain, in which C2 domain inhibits Nedd4 function [58]. Identification of the detailed interaction surface between Nedd4 and Pax7 might be important to understand molecular determinants of Pax7 ubiquitination.

Nedd4 activity can be regulated via extrinsic stimuli. For example, tyrosine phosphorylation mediated by Src kinases in response to FGFR activation antagonizes C2 domain mediated auto-inhibition to activate its ubiquitin-ligase activity [59]. Thus, complete mechanisms connecting SC niche signaling with Nedd4 activity are still missing and could be relevant to understand Pax7 regulation in quiescent and activated SCs. In this line, a critical subject is the relationship between post-translational and post-transcriptional regulation of Pax7, since microRNA-dependent Pax7 decrease has been described during the proliferation-to-differentiation transition in primary mouse myoblasts [60]. Accordingly, hypoxic conditions favor quiescence/self-renewal in proliferating myoblasts by up regulating Pax7 expression, via a mechanism involving Notch-dependent repression of miR-1 and miR-206 expression [61].

We provided evidence indicating that Nedd4 shuttles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus in a myogenic context (Fig. 4). Moreover, Nedd4 nuclear localization appears to be under fine control, since LMB treatments of single myofiber-associated SCs indicate that Nedd4 is not transported to de nucleus at early stages of SC activation (Fig. 4). Transient disruption of Nedd4 nuclear export was sufficient to decrease Pax7 levels (Fig. 4–5). Most significantly, this nuclear Nedd4-dependent Pax7 decline results in precocious differentiation induction (Fig. 5), while Nedd4 knockdown correlates with retention of Pax7 protein, decreased Pax7 ubiquitination and impaired terminal differentiation. Thus, Nedd4 nuclear import/export appears to be a rate-limiting step and subject to specific regulation in myogenic cells, since Nedd4 over-expression in C2C12 or C3H10T1/2 cells co-expressing Pax7 results in accumulation of Nedd4 at the cytoplasm, while no significant changes in Pax7 levels were observed prior to differentiation induction (Bustos and Olguin, unpublished observations).

Physiological relevance of UPS/Nedd4 mediated Pax7 regulation

SCs-specific Pax7 knockout mouse models show dramatic loss of muscle regenerative capacity [12, 13]. Furthermore, recent findings showing that persistent Pax7 expression may underlie SC dysfunction during cancer cachexia [62], indicate that deregulation of Pax7 levels may play a role in diseased muscle.

UPS-dependent regulation appears to be critical for stem cell function [63–67], including muscle precursor differentiation [68–70]. In this scenario, ubiquitination could function to connect extrinsic and/or intrinsic pathways to regulate the Pax7:MyoD ratio, and thus, influence muscle progenitor cell fate. We believe our findings are relevant not only to understand how Pax7 protein levels are regulated during muscle cell differentiation, but also to establish UPS and Nedd4 as important determinants of SCs function and muscle tissue maintenance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Adult primary myoblasts and isolated myofibers were obtained as described [15] and cultured in growth medium [F12-C (Life technologies, USA), 15% horse serum (HS) (Hyclone, USA), 1nM FGF-2] at 37°C with 5% CO2. When required, myoblasts and myofibers were cultured in differentiation medium [F12-C, 7.5% HS].

C2C12 and C3H10T1/2 cell lines were maintained in growth medium [DMEM (Life technologies, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, USA)] at 37°C with 5% CO2. For differentiation assays C2C12 myoblasts were seeded and maintained in differentiation medium [DMEM+5% HS]. 48 h post differentiation induction, 0.1nM 1-β-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine (AraC) (EMD Millipore, USA) was added for 48 h. For ubiquitination assays, C3H10T1/2 cells were subjected to myogenic conversion, as described [15]. When required, cells were incubated with 0.5–25μM MG132, 1–5μM epoxomicin or DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 6 h prior to lysis or fixation. When required, cells were treated with 30nM Leptomycin-B (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) or vehicle for 6 h prior to fixation or lysis.

Subcellular fractionation

Cells were collected in cold PBS and resuspended in buffer A (10mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1.5mM MgCl2, 10mM KCl, 1mM DTT, protease inhibitors) and incubated 30 min on ice. Cells were passed 40 times through a 25G x 5/8 needle, and centrifuged at 700g for 5 min at 4°C; supernatant was stored as cytoplasmic fraction. Pelleted fraction was then washed three times in buffer A, resuspended in buffer B (20mM HEPES pH 7.9, 420mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.2mM EDTA, 1mM DTT and 25% glycerol), incubated on ice for 20 min and centrifuged 2 min at 14.000rpm and 4°C to obtain soluble nuclear fraction.

Plasmid and siRNA transfection

pRSV-MyoD, pCDNA3-Pax7d, pCDNA3-myc-NLSPax7FL, pCDNA3-myc-NLSPax7ΔC, pCDNA3-myc-NLSPax7ΔN, pCDNA3-myc-NLSPax7ΔHD plasmids were described previously [16]. pCS2-UbHA, pCAGGS-UbHA-WT, pCAGGS-UbHA-K48R, pCAGGS-UbHA-K0 and gap43-mRFP plasmids were donated by Dr. Juan Larraín (Santiago, Chile). pCDNA3-UbWT-6xHis y pCDNA3-UbK0-6xHis were donated by Dr. Dimitris Xirodimas (Montepellier, France). pCMV7-myc-6xHis-Ub was donated by Dr. Kristen Bjorkman (Boulder CO, USA) EYFP-MEM plasmid was obtained from Clontech, USA. pBiFC-bFos-VC155, and pBiFC-bJun-VN155(I152L) were previously described [73] and obtained from Dr. Chang-Deng Hu, (IN, USA). pBiFC-Pax7-VC155 was generated by PCR cloning Pax7d cDNA from pCDNA3-Pax7d. Primers were, FW: 5′-CCGGAATTCGGATGGCGGCCCTTCCC-3′, RV: 5′-CCGCTCGAGAGTAGGCTTGTCCCGTTTCCA-3′. pBiFC-Ub-VN155(I152L) was generated by PCR cloning of HA-ubiquitin cDNA from pCS2-UbHA. Primers were, FW: 5′-CCGGAATTCATGCAGATCTTCG-3′ RV: 5′-CCGCTCGAGCCCACCTCTCAGACG-3′. EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites were used for directional insertion in pBiFC-VC155 and pBiFC-VN155(I152L) backbones. Fusion protein generation and expression was confirmed via Western blot.

For knockdown, Nedd4 siRNAs-pool (QIAGEN, USA) and siCONTROL RISC-free siRNA (Dharmacon, USA) were used. Expression vectors and siRNAs were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life technologies, USA) according the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL, protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and 10–30μg of total protein was loaded into 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes for Western blotting with the following primary antibodies and dilutions: mouse monoclonal anti-Pax7, 1:10; mouse monoclonal (F5D) anti-myogenin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, USA), 1:5; mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin, 1:10000; mouse monoclonal anti-HA HRP conjugated, 1:4000 (Sigma-Aldrich,USA); mouse monoclonal anti-HDAC2 [3F3], 1:5000; rabbit polyclonal ChiP-grade anti-HA tag, 1:10000; rabbit polyclonal anti-Nedd4, 1:10000; rabbit monoclonal anti-GFP E385, 1:5000 (Abcam, UK); mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (EMD-Millipore, USA), 1:10000; mouse monoclonal 9B11 myc-tag (Cell Signaling, USA), 1:1000; rabbit polyclonal anti-GST (gift from Dr. María Paz Marzolo, Santiago, Chile), 1:5000 and mouse monoclonal P4D1 anti-ubiquitin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), 1:500. As secondary antibodies HRP conjugated anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, USA) were used at 1:5000. HRP activity was detected using the SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, USA). When indicated, lysates/fractions were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation as described [16].

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehide for 20 min and subjected to standard indirect immunofluorescence [16]. Primary antibodies and dilutions were as following: mouse monoclonal anti-Pax7 1:5 and mouse monoclonal anti-MHC (MF20), 1:2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, USA),; rabbit polyclonal anti-myogenin M-225 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), 1:200; chicken anti-Syndecan-4 [74] 1:500; rabbit polyclonal anti-Nedd4 (Abcam, UK), 1:1000. Secondary antibodies and dilutions were: goat anti-mouse Alexa 594, 1:500; goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488, 1:500; goat anti-mouse Alexa488, 1:500 (Life technologies, USA) and donkey anti-chicken-AMCA (Jackson IR, USA), 1:500. Vectashield (Vector labs, USA) was used for mounting. Images were acquired using an IX71 microscope (Olympus, USA) equipped with a QICam FAST QImaging camera or an Eclipse C2 spectral imaging confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Muscle section staining

Tibialis anterior muscles from 2–3 month-old female B6D2F1/J or C57BL/6J mice were dissected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen-chilled isopentane and cryosectioned (10μm thickness) for indirect immunofluorescence [16]. Primary antibodies and dilutions were: rat monoclonal anti-Laminin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 1:2000 and rabbit polyclonal anti-Nedd4 antibody (Abcam, UK) at 1:1000. Donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa-555, goat anti-mouse Alexa 594 and donkey anti-rat IgG Alexa-488 (Life technologies, USA) were used as secondary antibodies at 1:500 dilution. Slides were mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector labs, USA), and imaged for analysis using a BX61 (Olympus, USA) or a Diaphot Eclipse E600 microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Ubiquitin-mediated fluorescence complementation

General protocol was performed as described previously [35, 73] with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were transfected with plasmids encoding C-terminus fragment of Venus Fluorescent protein (VC155) fused to Pax7- or bFos- and N-terminus fragment of Venus (VN155-I152L) fused to ubiquitin -or bJun- as specified. Gap43-mRFP was included as a transfection marker. 24 h post transfection, fluorescence was evaluated in living cells, using an IX71 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus, USA) equipped with a QICam FAST QImaging digital camera. When indicated, 10μM MG132 or DMSO was added 6 h prior to examination.

Cell-based ubiquitination

Cells were transfected with Pax7 and myc-6xHis-ubiquitin, induced to differentiate for 48 h, and subjected to a His-ubiquitin based assay as described [75] with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were treated with 25μM MG132 for 6 hours and harvested in ice-cold PBS. Cells were pelleted for 10 minutes at 1000rpm, resuspended in buffer A2 (6M guanidine chloride, 0.1M Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 and 10mM immidazole, pH 8.0) and incubated with 50μl of Ni-NTA agarose (QIAGEN, USA) for 3 h at room temperature. After binding, Ni-NTA beads were washed twice with buffer A2, twice with buffer A2/TI (1 volume of buffer A2 and 3 volumes of buffer TI) and once with buffer TI (25mM Tris-HCl, 20mM imidazole, pH 6.8). Proteins were eluted with buffer ETI (25mM Tris-HCl, 300mM imidazole, pH 6.8) for 10 minutes at room temperature and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

GST pull-down

5μg of GST or GST-Pax7 were incubated with 0.25μg of Nedd4 in GST pull-down buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors) for 20 h at 4°C and then incubated with 10% v/v glutathione-agarose beads (Thermo Scientific, USA) 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed with GST pull-down buffer supplemented with 300mM NaCl. SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling was use to obtain eluted fractions for further analysis. Alternatively, [35S]-labeled proteins were obtained by coupled in vitro translation in rabbit reticulocyte extracts (Promega, USA) as described and pulled-down with GST or GST-Pax7.

In vitro ubiquitination

1μg of GST-Nedd4 or GST-only were pre-bound to 50μl glutathione-agarose beads (Thermo Scientific, USA) for 2 h at 4°C in pull-down buffer. Immobilized GST-proteins were incubated with 5μg of purified Pax7 protein in a 100μl reaction containing: 10μg of recombinant HA-Ubiquitin, 200ng of Ubiquitin Activating Enzyme UBE1 (E1), 300ng of UbcH5b (E2), 1X Energy regeneration solution (ERS) (Boston Biochem, USA), and 50mM HEPES, pH 7.5 buffer. After 1h incubation at 30 °C, supernatants were recovered for further analysis. Presence of Nedd4 in gluthatione-agarose beads was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. S3B). E3 activity was determined by detection of auto-ubiquitinated Nedd4 in parallel assays (data not shown), as described [57].

Alternatively 5μg of GST-Pax7 or GST-only proteins were incubated in a 50μl reaction with S-100 HeLa cell fraction 3.7mg/ml as UPS source, supplemented with 5μg of HA-ubiquitin, 1X ERS and 8μM MG132 and 250ng/μl ubiquitin aldehyde (Boston Biochem, USA). Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 1 h and diluted in 500μl of GST pull-down buffer prior to analysis.

Data analysis

Data is presented as representative experiments and quantifications are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three biological replicates. For immunofluorescence analysis at least 1000 cells -from three experimental replicates- were analyzed per treatment, unless indicated. For Western blots, densitometry analyses were performed using ImageJ software (NIH). Data was plotted in Excel (Microsoft, USA) or GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad software Inc., USA). Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed to determine statistical significance. Immunofluorescence images were processed using Photoshop and final figures were assembled using Illustrator (Adobe, USA).

Ethical issues

Mice procedures were performed according to National Commission for Science and Technology (CONICYT) guidelines and approved by Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile bioethics and biosecurity committee.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE S1. Pax7 interacts with UPS-related proteins during myogenesis.

A, (i), General strategy for identifying Pax7-interacting proteins by mass spectrometry. (ii) Approximate equimolar Pax7 and MyoD expression levels were confirmed via Western blotting (Lower panel, highlighted box). (iii) MG132 treatment results in an increase of ectopic Pax7 protein levels. C3H10T1/2 cells were transfected with Pax7 and MyoD at the indicated ratio and induced to differentiate for 48 h prior to vehicle or MG132 treatment and Western blotting. GFP was used as a transfection control. (iv) C2C12 cells were transfected with Pax7-VC and cells were induced to differentiate for 48 h prior to vehicle or MG132 treatment and Western blotting. GAPDH protein was used as a loading control.

B, (i) Identified Pax7 interacting candidates are detailed. Note that, as described previously [16], MyoD-Pax7 interaction was also detected in this analysis (*). Black box: Pax7-interacting candidates involved in protein turnover regulation via UPS. (ii) In vitro pull-down assays using purified recombinant GST-Pax7 and [35S]-methionine labeled in vitro-translated candidates were performed to validate mass spectrometry data. A subset of these candidates (bold) was enriched in the GST-Pax7 pull-down fraction, suggesting direct physical interaction.

FIGURE S2: Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) shows Pax7 ubiquitination in C2C12 cells.

A, Upper panel: Schematic representation of the principle used in this assay. bFos-bJun or Pax7-Ubiquitin interaction partners are fused to complementary non-fluorescent fragments of Venus protein (VC and VN). Venus fluorescence reconstitution is mediated by partner protein’s interaction. Lower panel: BiFC in living C2C12 cells. For quantifications, cells transfected with bFos-VC/bJun-VN or Pax7-VC-Ubiquitin-VN were classified into two categories, BiFC positive (arrows) or BiFC negative cells. Scale bar: 10μm.

B, Pax7 ubiquitination is observed in cell nucleus via BiFC in fixed C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells were transfected with bFos-VC/bJun-VN or Pax7-VC/Ubiquitin-VN and treated with MG132 6 h prior to cell fixation, mounting and fluorescence microscopy analysis. Arrows indicate positive BiFC cells. Scale bar: 10μm.

C, Pax7 can be monoubiquitinated during myogenic conversion. C3H10T1/2 cells were co-transfected with MyoD, Pax7 plus WT or mutant HA-Ub. Denaturing-IP for Pax7 followed by Western blot for HA show equivalent monoubiquitinated Pax7 species in all conditions (arrowhead).

FIGURE S3. A. Nuclear export inhibition induces 14-3-3 proteins nuclear accumulation. Proliferating C2C12 cells were treated with vehicle or 50 nM Leptomycin B (LMB) 6 h prior to cell fixation and immunofluorescence analysis for total 14-3-3 isoforms (rabbit polyclonal anti pan 14-3-3 antibody (K-19) Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA at 1:100). Note that LMB treatment results in strong nuclear accumulation of 14-3-3 protein (arrows) Scale bar: 10μm.

B, GST-Nedd4 and GST-only are retained by glutathione agarose beads. Eluates obtained from beads containing GST-Nedd4 or GST-only proteins were separated by centrifugation from Pax7 in vitro ubiquitination reaction and analyzed by Western blot. Note that ubiquitinated high molecular weight proteins (probably Nedd4 self-ubiquitinated species) are observed only in the presence of GST-Nedd4.

FIGURE S4: Leptomycin B (LMB) pretreated C2C12 cells show precocious Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) expression.

C2C12 cells were treated with vehicle or 50 nM LMB 6 h, washed and induced to differentiation for 48 h prior to fixation and immunofluorescence analysis to determine MyHC (monoclonal anti-MyHC antibody (MF-20) DSHB, Iowa City, IA, USA at 1:5) and Myogenin expression. Note that LMB treated cells show an increased number of MyHC positive cells compared to control (arrows). Note that it is possible to observe a higher number of Myogenin(+)/MyHC(−) cells in the control condition (arrowheads). Despite cells expressing MyHC are determined to terminal differentiation, no fusion is observed due to the short experimental time windows. Scale bar: 50μm. Lower panel: Quantification of the MyHC positive cells per field. (mean ± s.e.m.) after LMB treatment. Student’s t test *p<0.005.

Significance Statement.

Transcription factor Pax7 is a crucial regulator of adult muscle stem cell specification, maintenance and renewal. Little is known however about the mechanisms that control Pax7 function in order to orchestrate muscle stem cell activation, differentiation and renewal. Here we show that Nedd4 regulates Pax7 protein levels through the ubiquitin proteasome system, therefore affecting muscle stem cell fate.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Juan Larrain for Ub-HA, UbK48R, UbK0 and gap43mRFP plasmids, Dr. Sharad Kumar for mNedd4, Dr. Chang-Deng Hu for VC155 and VN155(I152L) and Dr. Dimitris Xirodimas for the pCDNA3-UbWT-6xHis y pCDNA3-UbK0-6xHis constructs. We are indebt to Dr. Enrique Brandan, Dr. Felipe Court and Dr. María Paz Marzolo for reagents and access to indispensable equipment. We greatly appreciate Dr. Patricia Burgos, Pamela Farfán and Dane Lund for troubleshooting with us UPS related protocols. Finally, we thank all members from the Olguín lab for valuable discussions and suggestions.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FONDECYT) [grant number 1130631] to HO; International Research Visit Fellowship from Fellowship “Becas-Chile” and Doctoral Thesis Support Fellowship AT- 24121135 from CONICYT to FB; Institutional Fellowship for graduate students (VRI-PUC) to EdV and support for EdV and FC from National Doctoral Fellowship, CONICYT. Funding for DDWC has been provided by NIH AR062836. Funding for JRY has been provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants P41 GM103533, R01 MH067880, UCLA/NHLBI Proteomics Centers (HHSN268201000035C). Funding for BBO has been provided by NIH AR049446.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Francisco Bustos: conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. Eduardo de la Vega: data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. Felipe Cabezas: data collection, analysis and interpretation. James Thompson: data collection, analysis and interpretation. DD Cornelison: reagents/equipment/analysis tools and data analysis. BB Olwin: reagents/equipment/analysis tools and data analysis. John Yates: reagents/equipment/analysis tools and data analysis. Hugo C. Olguin: conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing.

References

- 1.Lepper C, Partridge TA, Fan C-M. An absolute requirement for Pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. DEVELOPMENT. 2011;138(17):3639–3646. doi: 10.1242/dev.067595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Mathew SJ, et al. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. DEVELOPMENT. 2011;138(17):3625–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sambasivan R, Yao R, Kissenpfennig A. Pax7-expressing satellite cells are indispensable for adult skeletal muscle regeneration. 2011 doi: 10.1242/dev.067587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi X, Garry DJ. Muscle stem cells in development, regeneration, and disease. GENES & DEVELOPMENT. 2006;20(13):1692–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.1419406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MAURO A. Satellite cells of skeletal muscle fibers. J BIOPHYS BIOCHEM CYTOL. 1961;9:493–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultz E, Gibson MC, Champion T. Satellite cells are mitotically quiescent in mature mouse muscle: an EM and radioautographic study. J EXP ZOOL. 1978;206(3):451–456. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402060314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciciliot S, Schiaffino S. Regeneration of mammalian skeletal muscle. Basic mechanisms and clinical implications. CURR PHARM DES. 2010;16(8):906–914. doi: 10.2174/138161210790883453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chargé SBP, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. PHYSIOL REV. 2004;84(1):209–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassar-Duchossoy_etal2005_Pax3Pax7_GenDev2. 2005:1–6

- 10.Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, et al. A Pax3/Pax7-dependent population of skeletal muscle progenitor cells. NAT CELL BIOL. 2005;435(7044):948–953. doi: 10.1038/nature03594. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15843801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seale P, Sabourin LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, et al. Pax7 is required for the specification of myogenic satellite cells. CELL. 2000;102(6):777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Günther S, Kim J, Kostin S, et al. Myf5-positive satellite cells contribute to Pax7-dependent long-term maintenance of adult muscle stem cells. CELL STEM CELL. 2013;13(5):590–601. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maltzahn von J, Jones AE, Parks RJ, et al. Pax7 is critical for the normal function of satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle. PNAS. 2013;110(41):16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307680110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar D, Shadrach JL, Wagers AJ, et al. Id3 is a direct transcriptional target of Pax7 in quiescent satellite cells. MOL BIOL CELL. 2009;20(14):3170–3177. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olguín HC, Olwin BB. Pax-7 up-regulation inhibits myogenesis and cell cycle progression in satellite cells: a potential mechanism for self-renewal. DEV BIOL. 2004;275(2):375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.015. Available at: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=15501225&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olguín HC, Yang Z, Tapscott SJ, et al. Reciprocal inhibition between Pax7 and muscle regulatory factors modulates myogenic cell fate determination. J CELL BIOL. 2007;177(5):769–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608122. Available at: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=17548510&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zammit PS. Pax7 and myogenic progression in skeletal muscle satellite cells. J CELL SCI. 2006;119(Pt 9):1824–1832. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Lin G, Slack JMW. Control of muscle regeneration in the Xenopus tadpole tail by Pax7. DEVELOPMENT. 2006;133(12):2303–2313. doi: 10.1242/dev.02397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gros J, Manceau M, Thomé V, et al. A common somitic origin for embryonic muscle progenitors and satellite cells. NAT CELL BIOL. 2005;435(7044):954–958. doi: 10.1038/nature03572. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15843802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kassar-Duchossoy L, Giacone E, Gayraud-Morel B, et al. Pax3/Pax7 mark a novel population of primitive myogenic cells during development. GENES & DEVELOPMENT. 2005;19(12):1426–1431. doi: 10.1101/gad.345505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKinnell IW, Ishibashi J, Le Grand F, et al. Pax7 activates myogenic genes by recruitment of a histone methyltransferase complex. NAT CELL BIOL. 2007;10(1):77–84. doi: 10.1038/ncb1671. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18066051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Relaix F. Pax3 and Pax7 have distinct and overlapping functions in adult muscle progenitor cells. J CELL BIOL. 2006;172(1):91–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olguín HC, Pisconti A. Marking the tempo for myogenesis: Pax7 and the regulation of muscle stem cell fate decisions. J CELL MOL MED. 2012;16(5):1013–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01348.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olguin HC. Regulation of Pax7 protein levels by caspase-3 and proteasome activity in differentiating myoblasts. BIOL RES. 2011;44(4):323–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zammit PS, Golding JP, Nagata Y, et al. Muscle satellite cells adopt divergent fates: a mechanism for self-renewal? J CELL BIOL. 2004;166(3):347–357. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A. Targeting proteins for destruction by the ubiquitin system: implications for human pathobiology. ANNU REV PHARMACOL TOXICOL. 2009;49:73–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.051208.165340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. ANNU REV BIOCHEM. 1998;67(1):425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. ANNU REV BIOCHEM. 2001;70(1):503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotin D, Kumar S. Physiological functions of the HECT family of ubiquitin ligases. NAT REV MOL CELL BIOL. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nrm2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingham RJ, Gish G, Pawson T. The Nedd4 family of E3 ubiquitin ligases: functional diversity within a common modular architecture. ONCOGENE. 2004;23(11):1972–1984. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang B, Kumar S. Nedd4 and Nedd4-2: closely related ubiquitin-protein ligases with distinct physiological functions. CELL DEATH DIFFER. 2009 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar S, Harvey KF, Kinoshita M, et al. cDNA Cloning, Expression Analysis, and Mapping of the MouseNedd4Gene. GENOMICS. 1997;40(3):435–443. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koncarevic A, Jackman RW, Kandarian SC. The ubiquitin-protein ligase Nedd4 targets Notch1 in skeletal muscle and distinguishes the subset of atrophies caused by reduced muscle tension. THE FASEB JOURNAL. 2007;21(2):427–437. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6665com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagpal P, Plant PJ, Correa J, et al. The Ubiquitin Ligase Nedd4-1 Participates in Denervation-Induced Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Mice. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang D, Kerppola TK. Ubiquitin-mediated fluorescence complementation reveals that Jun ubiquitinated by Itch/AIP4 is localized to lysosomes. PROC NATL ACAD SCI US A. 2004;101(41):14782–14787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404445101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ben-Saadon R, Zaaroor D, Ziv T, et al. The polycomb protein Ring1B generates self atypical mixed ubiquitin chains required for its in vitro histone H2A ligase activity. MOLECULAR CELL. 2006;24(5):701–711. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carvallo L, Muñoz R, Bustos F, et al. Non-canonical Wnt signaling induces ubiquitination and degradation of Syndecan4. JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY. 2010;285(38):29546–29555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.155812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chau V, Tobias JW, Bachmair A, et al. A multiubiquitin chain is confined to specific lysine in a targeted short-lived protein. SCIENCE. 1989;243(4898):1576–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamilton MH, Tcherepanova I, Huibregtse JM, et al. Nuclear import/export of hRPF1/Nedd4 regulates the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of its nuclear substrates. J BIOL CHEM. 2001;276(28):26324–26331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kudo N. Leptomycin B Inhibition of Signal-Mediated Nuclear Export by Direct Binding to CRM1. EXPERIMENTAL CELL RESEARCH. 1998;242(2):540–547. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawabe Y-I, Wang YX, McKinnell IW, et al. Carm1 Regulates Pax7 Transcriptional Activity through MLL1/2 Recruitment during Asymmetric Satellite Stem Cell Divisions. CELL STEM CELL. 2012;11(3):333–345. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luan Z, Liu Y, Stuhlmiller TJ, et al. SUMOylation of Pax7 is essential for neural crest and muscle development. CELL MOL LIFE SCI. 2013;70(10):1793–1806. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1220-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao XR, Cao XR, Lill NL, et al. Nedd4 Controls Animal Growth by Regulating IGF-1 Signaling -- Cao et al. 1 (38): ra5 -- Science Signaling. SCIENCE SIGNALING. 2008;1(38):ra5. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1160940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fouladkou F, Lu C, Jiang C, et al. The ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1 is required for heart development and is a suppressor of thrombospondin-1. JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY. 2010;285(9):6770–6780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.082347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Oppenheim RW, Sugiura Y, et al. Abnormal development of the neuromuscular junction in Nedd4-deficient mice. DEV BIOL. 2009;330(1):153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boutet SC, Disatnik M-H, Chan LS, et al. Regulation of Pax3 by Proteasomal Degradation of Monoubiquitinated Protein in Skeletal Muscle Progenitors. CELL. 2007;130(2):349–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida N, Yoshida S, Koishi K, et al. Cell heterogeneity upon myogenic differentiation: down-regulation of MyoD and Myf-5 generates “reserve cells”. J CELL SCI. 1998;111(Pt 6):769–779. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deveraux Q, Ustrell V, Pickart C, et al. A 26 S protease subunit that binds ubiquitin conjugates. JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY. 1994;269(10):7059–7061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Husnjak K, Elsasser S, Zhang N, et al. Proteasome subunit Rpn13 is a novel ubiquitin receptor. NATURE. 2008;453(7194):481–488. doi: 10.1038/nature06926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ciechanover A, Breitschopf K, Hatoum OA, et al. Degradation of MyoD by the ubiquitin pathway: regulation by specific DNA-binding and identification of a novel site for ubiquitination. MOL BIOL REP. 1999;26(1–2):59–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1006964122190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. ANNU REV BIOCHEM. 2009;78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y, Ciechanover A. Non-canonical ubiquitin-based signals for proteasomal degradation. J CELL SCI. 2012;125(Pt 3):539–548. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McDowell GS, Philpott A. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BIOCHEMISTRY AND CELL BIOLOGY. 2013;45(8):1833–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y, Cohen S, Ciechanover A. Modification by single ubiquitin moieties rather than polyubiquitination is sufficient for proteasomal processing of the p105 NF-kappaB precursor. MOL CELL. 2009;33(4):496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin H, Gui Y, Du G, et al. Dependence of phospholipase D1 multi-monoubiquitination on its enzymatic activity and palmitoylation. JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY. 2010;285(18):13580–13588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Polo S, Sigismund S, Faretta M, et al. A single motif responsible for ubiquitin recognition and monoubiquitination in endocytic proteins. NATURE. 2002;416(6879):451–455. doi: 10.1038/416451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woelk T, Oldrini B, Maspero E, et al. Molecular mechanisms of coupled monoubiquitination. NAT CELL BIOL. 2006;8(11):1246–1254. doi: 10.1038/ncb1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiesner S, Ogunjimi AA, Wang H-R, et al. Autoinhibition of the HECT-type ubiquitin ligase Smurf2 through its C2 domain. CELL. 2007;130(4):651–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fang NN, Chan GT, Zhu M, et al. Rsp5/Nedd4 is the main ubiquitin ligase that targets cytosolic misfolded proteins following heat stress. NAT CELL BIOL. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ncb3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen J-F, Tao Y, Li J, et al. microRNA-1 and microRNA-206 regulate skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation and differentiation by repressing Pax7. J CELL BIOL. 2010;190(5):867–879. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu W, Wen Y, Bi P, et al. Hypoxia promotes satellite cell self-renewal and enhances the efficiency of myoblast transplantation. DEVELOPMENT. 2012;139(16):2857–2865. doi: 10.1242/dev.079665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.He WA, Berardi E, Cardillo VM, et al. NF-κB-mediated Pax7 dysregulation in the muscle microenvironment promotes cancer cachexia. J CLIN INVEST. 2013;123(11):4821–4835. doi: 10.1172/JCI68523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heuzé ML, Lamsoul I, Moog-Lutz C, et al. Ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. BLOOD CELLS, MOLECULES, AND DISEASES. 2008;40(2):200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moran-Crusio K, Reavie LB, Aifantis I. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cell fate by the ubiquitin proteasome system. TRENDS IN IMMUNOLOGY. 2012;33(7):357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Naujokat C, Šarić T. Concise Review: Role and Function of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in Mammalian Stem and Progenitor Cells. STEM CELLS. 2007;25(10):2408–2418. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reavie L, Gatta Della G, Crusio K, et al. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cell differentiation by a single ubiquitin ligase-substrate complex. NAT IMMUNOL. 2010;11(3):207–215. doi: 10.1038/ni.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tuoc TC, Stoykova A. Roles of the ubiquitin-proteosome system in neurogenesis. CC. 2010 doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gardrat F, Montel V, Raymond J, et al. Degradation of an ubiquitin-conjugated protein is associated with myoblast differentiation in primary cell culture. IUBMB LIFE. 1999;47(3):387–396. doi: 10.1080/15216549900201413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim SS, Rhee S, Lee KH, et al. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the myogenic differentiation of rat L6 myoblasts. FEBS LETTERS. 1998;433(1–2):47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mugita N, Honda Y, Nakamura H, et al. The involvement of proteasome in myogenic differentiation of murine myocytes and human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR MEDICINE. 1999;3(2):127–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. NAT BIOTECHNOL. 2001;19(3):242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cociorva DL, Tabb D, Yates JR. Validation of tandem mass spectrometry database search results using DTASelect. CURR PROTOC BIOINFORMATICS. 2007;Chapter 13(Unit 13.4) doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1304s16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kodama Y, Hu C-D. An improved bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay with a high signal-to-noise ratio. BIOTECH. 2010;49(5):793–805. doi: 10.2144/000113519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cornelison DDW, Wilcox-Adelman SA, Goetinck PF, et al. Essential and separable roles for Syndecan-3 and Syndecan-4 in skeletal muscle development and regeneration. GENES & DEVELOPMENT. 2004;18(18):2231–2236. doi: 10.1101/gad.1214204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jin L, Pahuja KB, Wickliffe KE, et al. Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of COPII coat size and function. NATURE. 2012;482(7386):495–500. doi: 10.1038/nature10822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1. Pax7 interacts with UPS-related proteins during myogenesis.

A, (i), General strategy for identifying Pax7-interacting proteins by mass spectrometry. (ii) Approximate equimolar Pax7 and MyoD expression levels were confirmed via Western blotting (Lower panel, highlighted box). (iii) MG132 treatment results in an increase of ectopic Pax7 protein levels. C3H10T1/2 cells were transfected with Pax7 and MyoD at the indicated ratio and induced to differentiate for 48 h prior to vehicle or MG132 treatment and Western blotting. GFP was used as a transfection control. (iv) C2C12 cells were transfected with Pax7-VC and cells were induced to differentiate for 48 h prior to vehicle or MG132 treatment and Western blotting. GAPDH protein was used as a loading control.

B, (i) Identified Pax7 interacting candidates are detailed. Note that, as described previously [16], MyoD-Pax7 interaction was also detected in this analysis (*). Black box: Pax7-interacting candidates involved in protein turnover regulation via UPS. (ii) In vitro pull-down assays using purified recombinant GST-Pax7 and [35S]-methionine labeled in vitro-translated candidates were performed to validate mass spectrometry data. A subset of these candidates (bold) was enriched in the GST-Pax7 pull-down fraction, suggesting direct physical interaction.

FIGURE S2: Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) shows Pax7 ubiquitination in C2C12 cells.

A, Upper panel: Schematic representation of the principle used in this assay. bFos-bJun or Pax7-Ubiquitin interaction partners are fused to complementary non-fluorescent fragments of Venus protein (VC and VN). Venus fluorescence reconstitution is mediated by partner protein’s interaction. Lower panel: BiFC in living C2C12 cells. For quantifications, cells transfected with bFos-VC/bJun-VN or Pax7-VC-Ubiquitin-VN were classified into two categories, BiFC positive (arrows) or BiFC negative cells. Scale bar: 10μm.

B, Pax7 ubiquitination is observed in cell nucleus via BiFC in fixed C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells were transfected with bFos-VC/bJun-VN or Pax7-VC/Ubiquitin-VN and treated with MG132 6 h prior to cell fixation, mounting and fluorescence microscopy analysis. Arrows indicate positive BiFC cells. Scale bar: 10μm.

C, Pax7 can be monoubiquitinated during myogenic conversion. C3H10T1/2 cells were co-transfected with MyoD, Pax7 plus WT or mutant HA-Ub. Denaturing-IP for Pax7 followed by Western blot for HA show equivalent monoubiquitinated Pax7 species in all conditions (arrowhead).

FIGURE S3. A. Nuclear export inhibition induces 14-3-3 proteins nuclear accumulation. Proliferating C2C12 cells were treated with vehicle or 50 nM Leptomycin B (LMB) 6 h prior to cell fixation and immunofluorescence analysis for total 14-3-3 isoforms (rabbit polyclonal anti pan 14-3-3 antibody (K-19) Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA at 1:100). Note that LMB treatment results in strong nuclear accumulation of 14-3-3 protein (arrows) Scale bar: 10μm.

B, GST-Nedd4 and GST-only are retained by glutathione agarose beads. Eluates obtained from beads containing GST-Nedd4 or GST-only proteins were separated by centrifugation from Pax7 in vitro ubiquitination reaction and analyzed by Western blot. Note that ubiquitinated high molecular weight proteins (probably Nedd4 self-ubiquitinated species) are observed only in the presence of GST-Nedd4.

FIGURE S4: Leptomycin B (LMB) pretreated C2C12 cells show precocious Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) expression.

C2C12 cells were treated with vehicle or 50 nM LMB 6 h, washed and induced to differentiation for 48 h prior to fixation and immunofluorescence analysis to determine MyHC (monoclonal anti-MyHC antibody (MF-20) DSHB, Iowa City, IA, USA at 1:5) and Myogenin expression. Note that LMB treated cells show an increased number of MyHC positive cells compared to control (arrows). Note that it is possible to observe a higher number of Myogenin(+)/MyHC(−) cells in the control condition (arrowheads). Despite cells expressing MyHC are determined to terminal differentiation, no fusion is observed due to the short experimental time windows. Scale bar: 50μm. Lower panel: Quantification of the MyHC positive cells per field. (mean ± s.e.m.) after LMB treatment. Student’s t test *p<0.005.