Abstract

Objective

Cigarette smoking is a prevalent problem among Latinos, yet little is known about what factors motivate them to quit smoking or make them feel more confident that they can. Given cultural emphases on familial bonds among Latinos (e.g., familismo), it is possible that communication processes among Latino spouses play an important role. The present study tested a mechanistic model in which perceived spousal constructive communication patterns predicted changes in level of motivation for smoking cessation through changes in self-efficacy among Latino expectant fathers.

Methods

Latino males (n = 173) and their pregnant partners participated in a couple-based intervention targeting males’ smoking. Couples completed self-report measures of constructive communication, self-efficacy (male partners only), and motivation to quit (male partners only) at four time points throughout the intervention.

Results

Higher levels of perceived constructive communication among Latino male partners predicted subsequent increases in male’s partners’ self-efficacy and, to a lesser degree, motivation to quit smoking; however, self-efficacy did not mediate associations between constructive communication and motivation to quit smoking. Furthermore, positive relationships with communication were only significant at measurements taken after completion of the intervention. Female partners’ level of perceived constructive communication did not predict male partners’ outcomes.

Conclusion

These results provide preliminary evidence to support the utility of couple-based interventions for Latino men who smoke. Findings also suggest that perceptions of communication processes among Latino partners (particularly male partners) may be an important target for interventions aimed increasing desire and perceived ability to quit smoking among Latino men.

Keywords: communication, self-efficacy, motivation, Latino, smoking

Latinos in the United States have only a slightly lower smoking prevalence as White Caucasians (13% vs. 19%; CDC, 2011), but are significantly less likely to quit (Pérez-Stable et al., 2001) and more likely to die from smoking-related illnesses (USCS, 2013). Spousal communication processes may be particularly relevant predictors of motivation for change among Latinos who possess cultural values emphasizing spousal and familial bonds, such as simpatia (i.e., general tendency to avoid interpersonal conflict and remain agreeable; Falicov, 2013) and familismo (i.e., collectivistic emphasis on remaining loyal and contributing to the wellbeing of the nuclear and extended family; Falicov, 2013). Moreover, family-related motivators to engage in healthy behavioral patterns (e.g., smoking cessation) might be especially pertinent to Latino men who also possess the cultural script of machismo (i.e., men’s responsibility to provide for, protect, and defend their family; Gonzalez & Acevedo, 2013) and particularly powerful during family-related life events (e.g., pregnancy) for expectant Latino fathers (Pollak et al., 2010). Further, according to Lewis and colleagues (2006), “[constructive] communication may encourage spouses to reflect on the roles, norms, and obligations of the relationship, which are thought to promote the cognitive and emotional considerations necessary for transformation of motivation” (p. 1376).

More specifically, constructive communication patterns between partners may positively impact Latino men’s motivation to quit smoking by increasing their confidence in their ability to do so (i.e., self-efficacy; Bandura, 1999). Specifically, romantic partners who are able to communicate in a way that is supportive, mutually respectful, direct, and non-violent might be better able to positively exchange information and skills, thus promoting a greater sense of self-efficacy to execute desired goals and improve behavioral health (Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, 2002). This increase in self-efficacy may promote greater motivation to engage in smoking behavior change, as is predicted by Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1991) and corroborating empirical research (e.g., Cupertino et al., 2012; Kelly, Zyzanski, & Alemagno, 1991). Though no previous studies have examined the effect of couple communication patterns on partners’ self-efficacy to quit smoking, better interspousal relationship functioning is thought to promote a greater sense of self-efficacy to execute desired goals (Coyne & Smith, 1994), which might then increase motivation, a important precedent to behavioral change such as smoking cessation (see Miller & Rollnick, 2012).

Based on these assertions, the present study tested a model in which perceived constructive communication patterns among Latino romantic partners predicted male partners’ later levels of motivation to quit smoking, specifically by increasing the smoker’s belief in his ability to quit. To test these pathways, the current project used longitudinal data from Latino couples who received a couple-based communication skills training intervention and completed contemporaneous assessments of perceived constructive communication, self-efficacy (males only), and motivation (males only) at four time points. This is a secondary analysis of The Parejas Trial, a randomized trial that examined the effectiveness of a brief couple-based intervention aimed at promoting health behaviors among Latino partners during pregnancy and postpartum (see Pollak et al., 2014). As the intervention effects on behavioral health outcomes are reported elsewhere (Pollak et al., 2014), the current study examined specifically how changes in motivational processes coincided with changes in communication patterns among couples who received the intervention. We hypothesized that (1) higher levels of perceived constructive communication in each partner would positively predict male partners’ motivation to quit smoking and (2) changes in male partners’ self-efficacy would mediate this relationship.

Methods

Participants

A total of 173 (50%) of the 348 couples who participated in the larger study were included in the present analyses (i.e., only those in the intervention arm). Demographic information for these participants is presented in Table 1. Eligible men were 18 years of age or older, living with their pregnant partner, of Hispanic ethnicity, and had smoked within the past 30 days. Eligible women were 16 years of age or older, living with their partner, 8–25 weeks pregnant, and not currently smoking. Follow-up rates were 86%, 78%, and 79% for end of pregnancy (28–35 weeks gestation), 3-months postpartum, and 12-months after baseline follow-ups, respectively. Results of attrition analyses revealed that participants who were lost to follow-up reported less household income and were more likely to report speaking only Spanish at home than those who completed the larger study.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and demographics

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 47.3 | 79 | 45.4 | 74 |

| African-American | 0.6 | 1 | 3.1 | 5 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1.8 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Mixed race | 47.3 | 79 | 49.1 | 80 |

| Other | 3.0 | 5 | 2.5 | 4 |

| Employment | ||||

| Full-Time | 64.0 | 110 | 14.0 | 27 |

| Part-Time | 29.1 | 50 | 11.6 | 19 |

| Unemployed | 7.0 | 12 | 74.4 | 126 |

| Education | ||||

| Grades 0–6 | 30.1 | 52 | 29.5 | 51 |

| Grades 6–9 | 32.9 | 57 | 37.0 | 64 |

| Grades 10–12 | 27.7 | 48 | 24.9 | 43 |

| Vocational Schooling | 0.6 | 1 | 1.2 | 2 |

| Some College | 6.4 | 11 | 4.0 | 7 |

| College Degree | 1.7 | 3 | 2.9 | 5 |

| Post Grad | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 |

| Monthly Individual Income | ||||

| $0–$500 | 24.4 | 40 | 18.4 | 27 |

| $501–$1,000 | 26.2 | 43 | 33.3 | 49 |

| $1,001 – $1,500 | 25.0 | 41 | 34.0 | 50 |

| $1,501 or more | 24.4 | 40 | 14.3 | 21 |

| Living Situation | ||||

| Married and living with partner | 33.5 | 58 | 33.5 | 58 |

| Unmarried but living with partner | 66.5 | 115 | 66.5 | 115 |

| Relationship Length | ||||

| Less than 6 months | 9.3 | 16 | 9.3 | 16 |

| 6 months – less than 2 years | 16.9 | 29 | 16.9 | 29 |

| 2–3 years | 10.5 | 18 | 10.5 | 18 |

| More than 3 years | 63.4 | 109 | 63.4 | 109 |

| Age (years) | M = 30.08 | SD = 6.39 | M = 28.18 | SD = 6.19 |

| Weeks Pregnant at Baseline | - | - | M = 16.55 | SD = 5.54 |

Procedures

All procedures of the larger study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Duke University Medical Center. Latino couples were recruited from two health service centers and through local outreach efforts in a midsized Southeastern city. Interested partners were informed about a study to help expectant fathers to quit smoking, expectant mothers to have better nutrition and physical activity, and pregnant couples to communicate more effectively about smoking. Eligible couples participated in a two-arm randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of a two-session, culturally-appropriate, couple-based, face-to-face treatment versus a control arm in which couples received a culturally-appropriate self-help smoking cessation guide. Four face-to-face surveys of the couples were conducted throughout the duration of the study: at baseline (Time 1), end of pregnancy (28–35 week gestation; Time 2), 3 months postpartum (Time 3), and 12 months from baseline (Time 4). Survey follow-ups coincided with intervention procedures such that the two-session face-to-face treatment protocol was completed by Time 2 and additional booster sessions and follow-up telephone calls were completed between Time 2 and Time 4. Each couple member was compensated for each survey completion with a $10 gift certificate.

Measures

Constructive Communication

Male partners’ and female partners’ perceived dyadic constructive communication patterns were assessed with the 7-item Constructive Communication subscale of the larger 32-item Communication Patterns Questionnaire (Heavey, Larson, Zumtobel, & Christensen, 1996). This scale measures percieved dyadic constructive communication behaviors about relationship issues in general (rather than about specific topics) and an example item includes “When some problem in the relationship arises, we both suggest possible solutions and compromises” which is rated on a 9-point scale (1 = Very unlikely to 9 = Very likely). Higher scores indicate adaptive, constructive communication behaviors between romantic partners. This subscale has demonstrated high internal consistency, high levels of interspousal agreement, and strong associations with other measures of marital adjustment (Hahlweg, Kaiser, Christensen, Fehm-Wolfsdorf, & Groth, 2000; Heavey et al., 1996). Internal reliability of this scale for male partners in the current study was .81, .78, .81, .85 at Time 1 through Time 4, respectively. Internal reliability of this scale for female partners in the current study was .81, .79, .82, .82 at Time 1 through Time 4, respectively.

Self-Efficacy

Male partners were asked about their level of self-perceived ability to stop smoking behaviors using a single Likert scale item. Male partners were asked how confident they feel to quit smoking at this time (1 = Not at all to 7 = Very much). This item is validated with Spanish-speaking Latino samples (Bock, Niaura, Neighbors, Carmona-Barros, & Azam, 2005).

Motivation

Male partners were asked about their desire to quit smoking using a single Likert scale item. Male partners were asked how much they want to quit smoking at this time (1 = Not at all to 7 = Very much). This item is validated with Spanish-speaking Latino samples (Bock et al., 2005).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 6.12. Full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used to handle missing data (Enders, 2010; Kline, 2011). Path analyses were used to test study hypotheses in a single three-variable four-wave panel model. Both male partners’ and female partners’ communication scores were included in the model to examine their unique effects on male partners’ self-efficacy and motivation. Following procedures outlined by Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, and Müller (2003), model fit was assessed using the chi-square test of model fit (a nonsignificant chi-square value indicates that the model has acceptable fit), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root-mean-square (SRMR) with the following cutoff values: CFI ≥ .95, TLI ≥ .95, RMSEA < .06, SRMR < .08. Because of significant positive intercorrelations between male and female partners’ communication scores (see Table 2), correlations between partner scores were specified at each time point of measurement within the path model. Next, the bias-corrected bootstrap method procedure (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004) was used to test whether male partners’ and female partners’ levels of constructive communication indirectly predicted increases in male partners’ motivation through increases in male partners’ self-efficacy. Thus, 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) were used to examine the significance of indirect effects of constructive communication on motivation through self-efficacy. According to this method, an indirect effect is significant at the .05 level if the value of 0 is not included in the bias-corrected confidence interval.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among study variables

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Men's CC | 52.55 | 10.18 | - | .53*** | .49*** | .49*** | .24** | .25** | .30** | .28** | .16* | .18** | .03 | .05 | .11 | .01 | .04 | .01 |

| 2. T2 Men's CC | 56.39 | 8.16 | - | .66*** | .73*** | .26** | .36** | .21* | .28** | .09 | .25** | .16* | .03 | .06 | .17** | .16* | .16* | |

| 3. T3 Men's CC | 57.60 | 7.71 | - | .84*** | .31** | .42** | .52** | .52** | .18* | .22* | .21* | .25** | .07 | .08 | .16* | . 16* | ||

| 4. T4 Men's CC | 57.45 | 8.34 | - | .42** | .40** | .51** | .51** | .16* | .25** | .15 | .24** | .01 | .05 | .16* | .17** | |||

| 5. T1 Women's CC | 52.05 | 10.57 | - | .48*** | .61*** | .57*** | .04 | .01 | .07 | .02 | .05 | .11 | .00 | .01 | ||||

| 6. T2 Women's CC | 55.34 | 8.01 | - | .47*** | .52*** | .04 | .05 | .06 | .04 | .06 | .03 | .01 | .07 | |||||

| 7. T3 Women's CC | 56.49 | 8.76 | - | .84*** | .02 | .11 | .10 | .17 | .03 | .05 | .16 | .07 | ||||||

| 8. T4 Women's CC | 56.20 | 8.71 | - | .08 | .16 | .13 | .29 | .01 | .13 | .13 | .15 | |||||||

| 9. T1 SE | 6.10 | 1.27 | - | .38** | .28** | .33** | .29** | .28** | .18* | .33** | ||||||||

| 10. T2 SE | 6.15 | 1.16 | - | .42** | .37** | .21* | .48** | .33** | .41** | |||||||||

| 11. T3 SE | 6.27 | 1.10 | - | .64** | .26** | .40** | .70** | .63** | ||||||||||

| 12. T4 SE | 6.27 | 1.22 | - | .20* | .38** | .43** | .60** | |||||||||||

| 13. T1 Motivation | 6.31 | 1.20 | - | .47** | .34** | .42** | ||||||||||||

| 14. T2 Motivation | 6.40 | 1.13 | - | .46** | .45** | |||||||||||||

| 15. T3 Motivation | 6.42 | 1.12 | - | .67** | ||||||||||||||

| 16. T4 Motivation | 6.49 | 1.03 | - |

Note. CC = Constructive communication. SE = Self-efficacy.

T1 = Baseline. T2 = End of pregnancy (28–35 weeks gestation). T3 = 3-months postpartum. T4 = 12-months after baseline.

p<.001

p < .01

p < .05.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for variables of interest across time points are presented in Table 2. As expected, individual variables were autocorrelated positively across time points. Additionally, the sample means indicated that each variable increased over time. Correlational analyses also revealed that male partners’ motivation was positively related to self-efficacy across time points, and that male partners’ self-efficacy and motivation were positively related to male partners’ (but not female partners’) constructive communication scores, but only at post-intervention time points.

Path Analyses

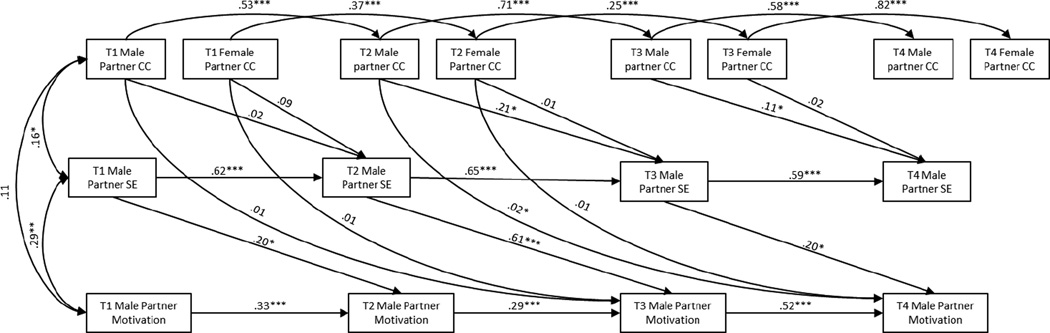

Results of path analyses are displayed in Figure 1. Model fit statistics indicated that the model fit the data well, χ2 (55, 173) = 67.11, p = .13, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .98, TLI = .98, SRMR = .07. Paths representing temporal stability were significant and demonstrated mostly moderate to large effect sizes, indicating that all three constructs were relatively stable over time. Results also showed that higher levels of male partner’s self-efficacy at all time points significantly predicted subsequent increases in male partner’s motivation at following time points. Additionally, results showed that neither male nor female partners’ prepartum constructive communication before intervention procedures (i.e., Time 1) predicted male partners’ subsequent self-efficacy or motivation. However, male partners’ (but not female partners’) constructive communication after receiving the couple-based intervention (but still before the birth of the child; Time 2), significantly predicted subsequent increases in male partner’s post-partum self-efficacy and motivation. Finally, significant associations among male partner’s constructive communication and self-efficacy remained significant at time points that were both post-intervention and postpartum (Time 3–4).

Figure 1.

Path diagram of the associations between constructive communication, self-efficacy, and motivation to quit smoking

Note. CC = Constructive communication. SE = Self-efficacy. T1 = Baseline. T2 = End of pregnancy (28–35 weeks gestation). T3 = 3-months postpartum. T4 = 12-months after baseline. Intercorrelations between male and female partners’ communication scores (see Table 2) were specified at each time point of measurement within the path model, but are not shown in the figure.

Standardized estimates are shown.

***p<.001 **p < .01 *p < .05.

Mediation Analyses

Results of mediational tests revealed that neither male partners’ (β = .04, CI = [−.439, .358]) nor female partners’ (β = .01, CI = [−.635, .205]) constructive communication at Time 1 predicted male partners’ motivation to quit smoking at Time 3 through self-efficacy at Time 2. Similarly, neither male partners’ (β = .08, CI = [−.125, .290]) nor female partners’ (β = .01, CI = [−.102, .076]) constructive communication at Time 2 predicted male partners’ motivation to quit smoking at Time 4 through self-efficacy at Time 3.

Discussion

Overall, higher levels of constructive communication among Latino male partners who smoke were associated with greater self-efficacy and, to a lesser degree, motivation to quit smoking at post-treatment follow-ups. Non-significant mediational paths through self-efficacy suggest that other variables may play an important role in the link between more constructive communication processes and motivation in Latino men who smoke. Notably, significant communication-efficacy and communication-motivation paths were found only at late pregnancy time points that were post-intervention. These results suggest that changes in male partners’ communication with their partner occurred simultaneous to intervention procedures and that these changes were positively associated with men’s perceived self-efficacy and motivation to quit smoking. Corroborating theoretical assertions that healthier relational processes may bolster partners’ level of motivation for health behavior change (see Lewis et al., 2006), findings from the present study suggest that more constructive communication patterns among Latino spouses are positively associated with male partners’ subsequent perceived level of ability and desire to quit smoking, which are important precedents to the initiation and maintenance of behavioral change (Miller & Rollnick, 2012).

Moreover, findings provide promising initial evidence that couple-based communication skills training may be an effective method for increasing Latino men’s motivation to quit smoking and engage in healthier behavioral patterns. Given the small but significant associations between communication and male partners’ motivation to quit smoking, results from the current study should be considered preliminary until additional studies have replicated these findings. Additionally, causal inferences cannot be drawn from the current study and more research is needed to clarify the interrelated role of couple communication processes, self-efficacy, and motivation to change. Future studies should explore these relationships in more diverse samples and test if these associations are significant among non-Latinos and non-pregnant couples. Future research might also address limitations of the present study by utilizing objective measures of constructive communication and more detailed measures of self-efficacy and motivation, and examine the effect of communication processes on health behaviors (e.g., smoking cessation, alcohol use, daily smoking habits, etc.).

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by grant R01CA127307 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) awarded to the last author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. New York, NY, US: Psychology Press, New York, NY; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 1991;50(2):248–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bock BC, Niaura RS, Neighbors CJ, Carmona-Barros R, Azam M. Differences between Latino and non-Latino White smokers in cognitive and behavioral characteristics relevant to smoking cessation. Addictive behaviors. 2005;30(4):711–724. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2005–2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1207–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Smith DAF. Couples coping with a myocardial infarction: Contextual perspective on patient self-efficacy. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8(1):43–54. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.8.1.43. [Google Scholar]

- Cupertino AP, Berg C, Gajewski B, Hui SKA, Richter K, Catley D, Ellerbeck EF. Change in self-efficacy, autonomous and controlled motivation predicting smoking. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17(5):640–652. doi: 10.1177/1359105311422457. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105311422457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Latino families in therapy: Second Edition. Guilford Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M, Acevedo G. Clinical practice with Hispanic individuals and families: An ecological perspective. Multicultural perspectives in social work practice with families. 2013:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hahlweg K, Kaiser A, Christensen A, Fehm-Wolfsdorf G, Groth T. Self-Report and observational assessment of couples' conflict: The concordance between the communication patterns questionnaire and the KPI observation system. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(1):61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Heavey CL, Larson BM, Zumtobel DC, Christensen A. The Communication Patterns Questionnaire: The reliability and validity of a constructive communication subscale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996:796–800. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RB, Zyzanski SJ, Alemagno SA. Prediction of motivation and behavior change following health promotion: Role of health beliefs, social support, and self-efficacy. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32(3):311–320. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90109-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, DeVellis B, Sleath B. Interpersonal communication and social influence. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice, 3rd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 363–402. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM. Understanding health behavior change among couples: An interdependence and communal coping approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(6):1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate behavioral research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Stable EJ, Ramirez A, Villareal R, Talavera GA, Trapido E, Suarez L, McAlister A. Cigarette smoking behavior among US Latino men and women from different countries of origin. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(9):1424–1430. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1424. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.9.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak KI, Denman S, Gordon KC, Lyna P, Rocha P, Brouwer RN, Baucom DH. Is pregnancy a teachable moment for smoking cessation among US Latino expectant fathers? A pilot study. Ethnicity & health. 2010;15(1):47–59. doi: 10.1080/13557850903398293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak KI, Lyna P, Bilheimer AK, Gordon KC, Peterson B, Gao X, Fish LJ. Efficacy of a couple-based randomized controlled trial to help Latino fathers quit smoking during pregnancy and postpartum: The Parejas Trial. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2014 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0841. cebp-0841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of psychological research online. 2003;8(2):23–74. [Google Scholar]

- USCS. 1999–2009 Incidence and Mortality. [accessed 03.19.14];2013 Web-based Report, www.cdc.gov/uscs.