Abstract

As states continue to debate whether or not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a key consideration is the impact of expansion on the financial position of hospitals, including their burden of uncompensated care. Conclusive evidence from coverage expansions that occurred in 2014 is several years away. In the meantime, we analyzed the experience of hospitals in Connecticut, which expanded Medicaid coverage to a large number of childless adults in April 2010 under the ACA. With hospital-level panel data from Medicare cost reports, we used difference-in-differences analyses to compare the change in Medicaid volume and uncompensated care in the period 2007–13 in Connecticut to changes in other Northeastern states. We found that early Medicaid expansion in Connecticut was associated with an increase in Medicaid discharges of 7 to 9 percentage points, relative to a baseline rate of 11 percent, and 7 to 8 percentage point increase in Medicaid revenue as a share of total revenue, relative to baseline share of 9.5 percent.. Also, in contrast to the national and regional trends of increasing uncompensated care during this period, hospitals in Connecticut experienced no increase in uncompensated care. We conclude that uncompensated care in Connecticut was roughly one-third lower than what it would have been without early Medicaid expansion. The results suggest that ACA Medicaid expansions could reduce hospitals’ uncompensated care burden.

In debates about the Medicaid expansion in the Affordable Care Act (ACA), hospitals have argued forcefully that expansion would improve their financial position.[1] This argument was not enough to carry the day in all states: As of April 29, 2015, twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia had expanded their Medicaid programs.[2] In several of the remaining states, however, the debate about whether (or how) to expand Medicaid continues.

Multiple analysts have projected that one consequence of Medicaid expansion for hospital finances will be a reduction in uncompensated care.[3–5] Some early evidence suggests that Medicaid expansion has indeed reduced uncompensated hospital care. A recent report from the Department of Health and Human Services explored aspects of Medicaid expansion using data from five large for-profit hospital chains that operated in both expansion and nonexpansion states, and from hospital association surveys in three expansion states.[6] The analysis found that uninsured admissions fell and Medicaid admissions increased, with the largest changes occurring in states that implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion.

Several other studies also found that coverage expansions and contractions prior to the ACA led to decreases and increases, respectively, in uncompensated care. A recent study showed that significant Medicaid cuts in Tennessee and Missouri in 2005 led to increases in uncompensated care in those states.[7] Another study found that health reform in Massachusetts reduced bad debt (one component of uncompensated care) by 26 percent—a change that reflects the effects of both the state’s Medicaid expansion and its implementation of a health insurance exchange.[8]

To estimate the effect of Medicaid expansion—as opposed to Medicaid cuts or to the full package of coverage expansions included in the ACA—on all hospitals, rather than just for-profits, we looked at the experience of Connecticut, a state that expanded its Medicaid program immediately after passage of the ACA.

Prior to the ACA, parents and caretakers with incomes up to 185 percent of the federal poverty level were eligible for Medicaid in Connecticut.[9] Childless adults were eligible for limited medical assistance through the State Administered General Assistance program, a state-financed program with a limited benefit package, if they had incomes below 56 percent of poverty and had less than $1,000 in assets.[10] Higher-income adults who did not have access to affordable group insurance and who experienced difficulty paying nongroup premiums were also able to purchase subsidized coverage through the state-sponsored Charter Oak Health Plan. However, enrollment in this program was declining during our study period because of rising premiums.[11]

As of April 2010 Connecticut offered full Medicaid benefits to childless adults with incomes below 56 percent of poverty, regardless of assets. In contrast with the limited benefits that had been available previously, the full benefits now included an expanded provider network, as well as long-term care/skilled nursing facility services and home health care benefits.[10] This resulted in 46,000 new Medicaid enrollees by 2014.[12] Benjamin Sommers and coauthors have shown that Connecticut’s decision to expand eligibility in this way led to an increase in Medicaid coverage and a reduction in the number of uninsured among the state’s residents.[12] We investigated whether these changes in insurance coverage at the population level translated into an increase in the number of inpatients with Medicaid coverage and a reduction in the amount of uncompensated care provided by hospitals.

Four other states—New Jersey, Washington, Minnesota, and California—and the District of Columbia also chose to expand their Medicaid programs between 2010 and 2014. For various reasons, their experiences do not provide clean natural experiments for investigating the effect of Medicaid expansion on hospital uncompensated care.

New Jersey and Washington used the early opportunity for expansion under the ACA to fund existing state programs without expanding eligibility to new groups. As a result, no increase in insurance coverage was expected.[9] In general, expansions in Medicaid coverage will reduce uncompensated care only to the extent that they reduce the uninsured rate among hospitalized patients. To the extent that such expansions simply shift patients from one source of public coverage to another, uncompensated care will not change.

Similarly, early expansion did not appear to substantially affect the number of uninsured residents in the District of Columbia. Sommers and coauthors found an insignificant decrease in the uninsured rate among childless adults, but a significant increase in the uninsured rate among parents.[12]

Early expansion by California and Minnesota increased the number of people eligible for public insurance and therefore should have had a larger effect on coverage, compared to the situation in states that did not expand eligibility to new groups. However, because California and Minnesota did not implement the expansion until 2011 and because data on hospital uncompensated care are available only with a lag, at this point we have very little post-expansion data on these states.

States that are still deciding whether or not to expand Medicaid need information now on the potential costs and benefits of expansion. Our focus on a single state, Connecticut, offers insights into how expanding Medicaid to cover the uninsured affects hospitals’ uncompensated care.

Study Data And Methods

Data

The data we analyzed came from Medicare cost reports for fiscal years 2007–13. These reports are submitted annually by all Medicare-certified hospitals (essentially, all hospitals excluding Veterans Affairs and select children’s hospitals). We combined these annual reports to create a hospital-level data set with up to seven years of data per hospital. The full sample consisted of 30 hospitals in Connecticut and 404 hospitals in the comparison states, providing a total of 1,958 hospital-year observations.

The cost reports include information on the total number of hospital discharges and the number of discharges for certain payer types: Medicaid (Title 19 of the Social Security Act), Medicare (Title 18), and the Maternal and Child Health program (Title 5). We expected that after 2010 the Medicaid share of discharges would increase in Connecticut, compared to the other states, driven by the increase in childless adults enrolled in Connecticut’s Medicaid program. This increase should coincide with a decrease in uninsured discharges. However, to the extent that the early Medicaid expansion caused some individuals to shift from private to public coverage – a phenomenon known as “crowd out”private discharges could fall as well.

Unfortunately, the hospital cost reports do not provide separate measures of uninsured and privately insured discharges. Therefore, we could not directly estimate the extent to which the expansion of Medicaid reduced the number of uninsured patients instead of simply crowding out existing private coverage.

One measurable consequence of any decline in the number of uninsured patients should be a decline in uncompensated care. Uncompensated care is defined as the sum of charity care and bad debt deflated by the cost-to-charge ratio, minus payments from self-pay patients. Charity care is care for which there was no expectation of payment at the time of discharge, whereas bad debt arises from services for which the hospital billed but did not receive payment. As a practical matter, it is difficult to distinguish these two components of uncompensated care even when they are reported separately, because hospitals vary in their definitions of charity care.

It is sometimes argued that the difference between Medicaid reimbursements and the cost of providing care represents a form of uncompensated care. However, such shortfalls are not included in standard definitions of uncompensated care[13] or in the measure of uncompensated care reported in the Medicare cost reports.

Methods

It is important to note that starting in 2010 hospitals were required to report data on uncompensated care using more disaggregated categories than had been required previously, such as separately reporting charity care and bad debt and reporting uncompensated care amounts by the insurance status of the patient.. To create a consistent measure of uncompensated care over the study period, and to address the ongoing problem of distinguishing between bad debt and charity care, we aggregated the detailed categories in the post-2010 data to match the pre-2010 measures of uncompensated care. For details on the construction of uncompensated care measures and a comparison with American Hospital Association data, see online Appendix Exhibits 1 and 2.[14]

In the cost reports, uncompensated care is measured in terms of hospital charges. We applied hospital-specific cost-to-charges ratios from the cost reports to construct a measure of the cost of uncompensated care. We used a difference-in-differences approach to assess the impact of Connecticut’s early expansion. Specifically, we investigated whether the change in uncompensated care (or other outcomes of interest, such as the Medicaid share of discharges) after 2010 was larger in Connecticut than in other Northeastern states—specifically, Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. The comparison group excluded New Jersey, which as mentioned above was also an ACA early adopter but expanded Medicaid only to people who were previously covered by state and local programs, and Massachusetts, which implemented a major health insurance reform in 2007.

Limitations

One potential limitation of our data is that hospitals often file incomplete information in Medicare cost reports.[15] Although our data contained observations from 94 percent of the hospitals in Connecticut and 86 percent of those in the comparison states, hospital cost reports were sometimes missing information on Medicaid revenues and uncompensated care. To ensure that our results were not biased by sample selection, we tested whether the rate of item nonresponse changed differentially in Connecticut compared to the other states. Although nonresponse was slightly more common in Connecticut overall, the response rate did not change more in Connecticut than in other states after 2010. Thus, there is no reason to expect our estimates to be biased by nonresponse.

As an additional robustness check, we conducted analyses on a subsample of hospitals that were observed continuously over the study period. As we describe below, the results from this balanced panel were very similar to those from the full sample.

Another potential limitation of our analysis is one of external validity: Connecticut’s expansion may not be representative of the expansions that are currently under way in other states. One possible reason is that Connecticut used early expansion as an opportunity to expand an existing program, so some enrollees were already insured. However, Connecticut is not alone in this respect. At least fourteen of the states that chose to expand Medicaid in 2014 had some form of preexisting program in place.[12]

Another way in which Connecticut’s early experience differs from those of later expansions is that in 2010 Connecticut expanded eligibility to childless adults with incomes only up to 56 percent of poverty, instead of using the 133 percent threshold required by the ACA after 2014. Given the limited nature of the 2010 expansion, we expect the effects of the 2014 expansion to be greater than what we found for Connecticut.

A final limitation of our analysis is that observed reductions in uncompensated care may overstate the improvement in hospitals’ financial positions because of the way uncompensated care is measured. Hospitals that treat uninsured patients can count any difference between what those patients pay and the cost of the service as uncompensated care. In contrast, hospitals that treat Medicaid patients cannot count the difference between what Medicaid pays and the cost of the service—the shortfall—as uncompensated care. Therefore, Medicaid expansion would have improved Connecticut hospitals’ financial positions only if the state’s Medicaid reimbursement rate was higher than what the hospitals would have collected from uninsured people had they not gained Medicaid eligibility.

The connection between uncompensated care and financial position is further complicated by the fact that Connecticut’s Medicaid expansion led to some crowding out of existing private coverage.[12] Because private insurers typically reimburse more generously than state Medicaid programs, shifts from private coverage to Medicaid would negatively affect Connecticut hospitals’ financial positions.

Study Results

Nationally, roughly 58 percent of private hospitals are notfor-profit.[16] However, there is substantial variation across regions, with for-profit hospitals located disproportionately in Southern states.[17] The vast majority of hospitals in our sample were notfor-profit: 99 percent of discharges in Connecticut (where only one of thirty hospitals was for-profit) and 90 percent of discharges in the comparison states were from not-for-profit hospitals (Exhibit 1). The sole for-profit hospital in Connecticut did not report information on uncompensated care before expansion.

EXHIBIT 1.

Descriptive Statistics Characteristics Of Hospitals In 2007–09, Before Medicaid Was Expanded In Connecticut

| Connecticut hospitals |

Northeastern hospitals |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Outcome variables, per hospital year | ||||

| Medicaid discharges | ||||

| As share of all discharges | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| In levels (weighted) | 3,198 | 3,321 | 2,463 | 2,642 |

| Medicaid revenues | ||||

| As share of total revenues | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.12 |

| In levels ($M; weighted average) | 135.8 | 88.1 | 307.9 | 441.2 |

| Uncompensated care | ||||

| As share of total expenses | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| In levels ($M; weighted average) | 13.9 | 8.8 | 14.2 | 18.5 |

| Hospital and market characteristics | ||||

| Organizational status (weighted by discharges) | ||||

| Nonprofit | 0.99 | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.30 |

| For profit | 0.00 | —a | 0.03 | 0.18 |

| Public | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| Total hospital beds | 412 | 209 | 442 | 346 |

| County unemployment rate (%) | 6.1 | 1.7 | 6.3 | 1.9 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2007–09 Medicare cost report data. NOTES “Northeastern hospitals” are all hospitals in the states of Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont (the Northeast census region excluding, Connecticut and, as explained in the text, New Jersey and Massachusetts). “Uncompensated care” is the sum of charity care and bad debt charges deflated by the cost-to-charge ratio, minus payments from self-pay patients. Results in levels represent the annual average per hospital number of Medicaid discharges; the annual average per hospital amount of Medicaid revenue in millions of dollars; and the annual average per hospital amount of uncompensated care in millions of dollars. All statistics in the table – both shares and levels - are the mean for a hospital year, weighted by average hospital-level discharges in the pre-expansion period. The pre-expansion sample consisted of 646 hospital-year observations from 19 hospitals in Connecticut and 271 hospitals in the Northeast census region.

SD is standard deviation.

Connecticut had no for-profit hospitals during this period.

Average hospital size (measured by numbers of hospital beds) did not differ between facilities in Connecticut and those in the comparison states (Exhibit 1). In terms of baseline market characteristics, the average county-level unemployment rate was similar in Connecticut and the comparison states (6.1 percent versus 6.3 percent).

A comparison of baseline values for our dependent variables also suggested that the other Northeastern states represented a good control group for Connecticut. In 2007–09, Medicaid patients represented 11 percent of discharges in Connecticut and 10 percent in the comparison states (Exhibit 1), although Medicaid represented a smaller share of hospital revenues in Connecticut than in the other states. Uncompensated care as a share of total expenses was 3 percent in both Connecticut and the comparison group.

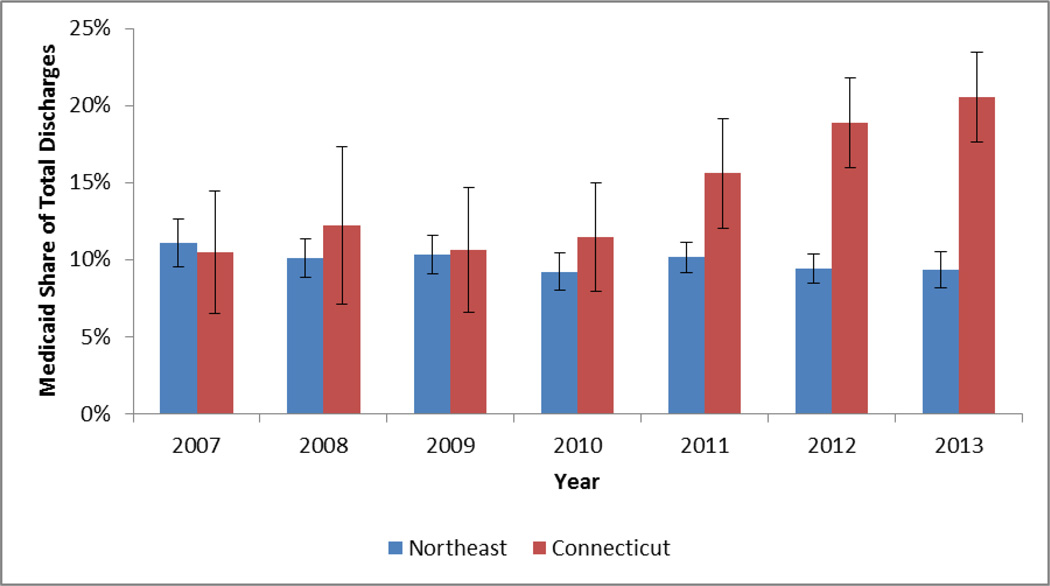

Exhibit 2 shows trends in Medicaid discharges as a share of total discharges from 2007 through 2013. We use Medicaid discharges during the pre-expansion period (2007–2009) as the denominator for calculating this share in both the pre-expansion and post-expansion periods because total discharges could have been affected by Connecticut’s expansion. Sommers and coauthors found large increases in Medicaid coverage at the population level in Connecticut, relative to neighboring states.[12] This pattern is evident in the hospitalized Connecticut population as well: Medicaid accounted for about the same fraction of discharges in Connecticut and other Northeastern states before 2010, as noted above, but the Medicaid share of discharges nearly doubled in Connecticut after 2010, while it fell insignificantly (p = 0.13) in the other states (Exhibit 2). In 2013, 21 percent of discharges in Connecticut were Medicaid enrollees, compared to 9 percent in the other Northeastern states (p < 0.01). Trends in Medicaid revenues show a similar pattern, increasing in Connecticut both in absolute terms and relative to the comparison states (see Appendix Exhibit 3).[14]

EXHIBIT 2.

Unadjusted Trends In Medicaid Discharges As A Share Of Total Discharges For Hospitals In Connecticut And Other Northeastern States, 2007–13

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2007–13 Medicare cost report data. NOTES The analysis sample included 1,985 observations from 434 hospitals in Connecticut and the comparison “Northeastern states” (Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont). In all years, Medicaid discharges are expressed as a fraction of total discharges in the period before Connecticut expanded Medicaid (2007–09). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

There are two channels through which Connecticut’s early expansion could have increased the number of Medicaid inpatients: by increasing inpatient utilization among newly insured people and by shifting the source of payment for people who would have been admitted anyway. The second channel includes both patients who otherwise would have been covered by private insurance and those who would have been uninsured. We examined two additional outcomes to shed light on the relative importance of these two channels. For results of these examinations, which are summarized below, see Appendix Exhibit 4.[14]

First, we examined trends in total discharges. The results indicated no significant change in Connecticut relative to either the baseline or the change in the other states. This null result for total discharges was consistent with findings from previous studies indicating that the use of inpatient care is relatively insensitive to insurance coverage. The most relevant evidence for our study is from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, which found no significant effect of Medicaid coverage on inpatient admissions.[18]

Second, we examined trends in discharges for patients with coverage other than Medicaid, Medicare, or other federal programs. Ideally, we would have looked separately at privately insured and uninsured patients. Unfortunately, as noted above, the Medicare cost reports do not break out these categories. The best we could do was to analyze an “all other”category of discharges for patients not covered by Medicaid or one of the federal programs enumerated in the Medicare cost reports, which will include both privately insured and uninsured patients as well as those covered by other state programs.

Looking at this “all other” category, we saw a significant decrease in Connecticut after 2010, relative to the change in other states. In 2013 the fraction of privately insured and uninsured discharges was 14 percentage points lower in Connecticut than in the comparison states (p < 0.01), a reduction of roughly the same magnitude as the increase in the share of Medicaid discharges. This result further suggests that the main effect of the expansion on hospitals was to change their payer mix instead of increasing their total volume.

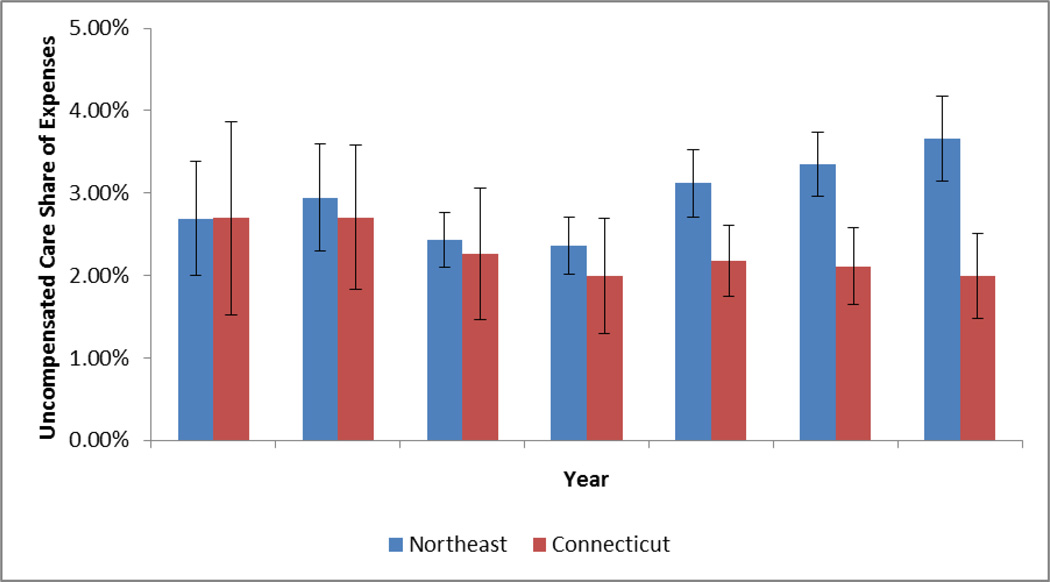

Our main interest was in determining whether expanding Medicaid coverage reduced the amount of uncompensated care provided by hospitals. Consistent with national statistics reported by the American Hospital Association,[13] uncompensated care expenditures increased in the comparison nonexpansion states beginning in 2011 (Exhibit 3). In contrast, we saw little change over time in uncompensated care as a fraction of total hospital expenditures in Connecticut. In 2013 uncompensated care as a share of total hospital expenditures was 1.8 percentage points lower in Connecticut than in the comparison states (p = 0.09), as a result of the increase in uncompensated care in those states. If we assume that the comparison states represent an appropriate counterfactual, this divergence suggests that Connecticut’s decision to expand Medicaid in 2010 fully offset an increase in uncompensated care that the state’s hospitals would have faced otherwise.

EXHIBIT 3.

Unadjusted Trends In Uncompensated Care As A Share Of Total Expenditures For Hospitals In Connecticut And Other Northeastern States, 2007–13

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2007–13 Medicare cost report data. NOTES The analysis sample included 1,985 observations from 434 hospitals in Connecticut and the comparison “Northeastern states” (Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont). In all years, uncompensated care is expressed as a fraction of total hospital expenditures in the period before Connecticut expanded Medicaid (2007–09). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

One question that cannot be answered by our analysis is why uncompensated care in the other Northeastern states increased during this period. Anecdotal reports suggest two possibilities. One is the increasing popularity of high-deductible plans,[19,20] and the other is the very slow economic recovery following the Great Recession.[21] Either of these phenomena would have affected Connecticut just as much as the comparison states; we conclude that Medicaid expansion in Connecticut offset what would have otherwise been an increased burden of uncompensated care because of these underlying dynamics.

It is important to note, however, that a simple interrupted time-series analysis that looked only at the flat trend in uncompensated care in Connecticut would conclude that the early expansion of Medicaid in 2010 had no effect on the amount of uncompensated care provided by hospitals]. The trend in comparison states provided information needed to understand what would likely have happened in Connecticut in the absence of early Medicaid expansion.

Regression

We estimated multivariate difference-in-differences models to account for the possibility that other factors affecting uncompensated care, such as hospital size or local economic conditions, may have been changing differentially in Connecticut versus the other Northeastern states during this period. The model also includes hospital and year fixed effects. (Exhibit 4).

EXHIBIT 4.

Effects Of Medicaid Expansion In Connecticut Over Time, Compared To Changes In Comparison States

| Mean | Difference-in- differences |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable |

Pre- expansion (2007– 09) |

Post- expansion (2011– 13) |

Difference between periods |

Unadjusted | Regression- adjusted |

| Medicaid discharges | |||||

| As share of total | 0.079*** | 0.094*** | |||

| Connecticut | 0.111 | 0.182 | 0.072 | ||

| Northeast | 0.104 | 0.097 | −0.007 | ||

| In levels | 1,895*** | 2,814*** | |||

| Connecticut | 3,198 | 4,589 | 1,391 | ||

| Northeast | 2,463 | 1,959 | −504 | ||

| Medicaid revenues | |||||

| As share of total | 0.076*** | 0.070*** | |||

| Connecticut | 0.095 | 0.182 | 0.086 | ||

| Northeast | 0.166 | 0.176 | 0.011 | ||

| In levels ($ millions) | 158.3** | 148.5*** | |||

| Connecticut | 135.8 | 356.6 | 220.9 | ||

| Northeast | 307.9 | 370.5 | 62.5 | ||

| Uncompensated care | |||||

| As share of total expenses | −0.011*** | −0.008 | |||

| Connecticut | 0.026 | 0.021 | −0.005 | ||

| Northeast | 0.027 | 0.033 | 0.006 | ||

| In levels ($ millions) | −5.1** | −3.8* | |||

| Connecticut | 13.9 | 11.4 | −2.5 | ||

| Northeast | 14.2 | 16.8 | 2.6 | ||

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2007–13 Medicare cost report data. NOTES The analysis sample included 1,744 observations from 434 hospitals in Connecticut and comparison states in the Northeast (Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont). Observations from 2010 were omitted from the analysis because for most hospitals the 2010 fiscal year included both months before and months after Connecticut’s implementation of the expansion of Medicaid. Results in levels represent the annual average per hospital number of Medicaid discharges; the annual average per hospital amount of Medicaid revenue in millions of dollars; and the annual average per hospital amount of uncompensated care in millions of dollars. All regressions were estimated using ordinary least squares and weighted by total discharges before expansion. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. To address the problem of] clustering at the state level with only seven clusters, we estimated corrected p values by reestimating our main models using a data set of state-by-year means, following Donald SG, Lang K. Inference with difference-in-differences and other panel data. Rev Econ Stat. 2007;89(2):221–33. The regression-adjusted model included year and hospital fixed effects, controls for for-profit status, bed size, and county-level unemployment rate.

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Consistent with Exhibits 2 and 3 the regression results indicate that after expansion, Medicaid discharges increased significantly in Connecticut relative to the trend in the other states. When Medicaid discharges were measured as a share of total discharges, the regression-adjusted difference-in-differences model implies that Connecticut’s early expansion increased the Medicaid share by 9.4 percentage points relative to the change in other states. This is an 85 percent increase relative to the baseline mean of 11.1 percent). We found a similar percentage increase for Medicaid discharges measured in levels and for Medicaid revenues as a share of total revenues. When the dependent variable was measured in dollars, the regression-adjusted model implies that Medicaid revenues more than doubled: a relative of increase of $148.5 million compared with a pre-expansion baseline of $135.8 million.

Turning to uncompensated care, the unadjusted difference-in-differences estimate implies that Connecticut’s early Medicaid expansion reduced uncompensated care as a percentage of total hospital expenses by approximately 1 percentage point, or roughly one-third of the baseline mean (0.026). The point estimate from the regression-adjusted model was a slightly smaller and insignificant 0.8 percentage points. Measured in dollars, the results were similar, although the regression-adjusted estimate was marginally significant with p = 0.11.

Alternative Analyses And Sensitivity Tests

To test the sensitivity of our results, we conducted the analysis on alternative samples using alternative regression specifications. The results from these alternative models (Appendix Exhibit 5)[14] were not qualitatively different from those reported in Exhibit 4.

For our first robustness check, we limited the sample to hospitals with complete data for the entire study period. This reduced the sample to fifty-two hospitals and 364 hospital-year observations, but it did not change the results materially. The difference-in-differences estimates for this balanced sample imply that the early expansion of Medicaid increased the Medicaid share of discharges in Connecticut by 10 percentage points relative to comparison states and reduced uncompensated care as a percentage of total expenditures by 0.66 percentage points, which was marginally significant with p = 0.10.

Because all of the Connecticut hospitals in our sample were notfor-profit, we reestimated the regressions on a sample that excluded for-profit hospitals in the comparison states. Our results were robust to this change as well: We found that Medicaid discharges increased by 9 percentage points, while uncompensated care fell by 0.81 percentage points.

Discussion

Connecticut was the first state to implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion by extending eligibility to childless adults who were not previously eligible for public insurance. The early expansion applied only to people with very low incomes (up to 56 percent of poverty). Nonetheless, it increased Medicaid enrollment by approximately 46,000 people and significantly reduced the number of uninsured adults.[10,12]

Our study investigated how this coverage expansion affected the provision of uncompensated care by hospitals in Connecticut. We found evidence that the volume of Medicaid discharges and revenue from Medicaid increased significantly. Uncompensated care in Connecticut did not increase, while it increased significantly in comparison states. This is consistent with preliminary evidence that since January 2014, hospitals in ACA expansion states have seen large increases in Medicaid patients.[6]

We also found that the implied reduction in the amount of uncompensated care in Connecticut relative to comparison states was much smaller than the increase in Medicaid revenue. One explanation for the difference in the size of these effects is that not all of the adults who gained Medicaid coverage in Connecticut were previously uninsured. In fact, Sommers and coauthors found that 40 percent of Connecticut’s new Medicaid enrollees already had coverage.[12]

Bad debt generated by insured patients accounts for a significant portion of hospital uncompensated care. However, moving patients from private insurance to Medicaid should have a smaller effect on uncompensated care than extending coverage to previously uninsured patients.

Because Medicaid payment rates are so much lower than those of private insurance, the substitution of public for private coverage tends to have a negative impact on total hospital revenues. We would expect crowd-out to be less of a factor for very poor adults, such as those who gained Medicaid coverage in Connecticut, than for the slightly higher income (but still poor) adults who gained coverage in subsequent expansions that increased Medicaid eligibility to 138% of poverty.. However, the degree of crowd-out that Sommers and coauthors found in Connecticut was greater than what has been projected for the ACA’s national Medicaid expansion.[12,22] Going forward, the impact of health reform on hospitals will depend to an important degree on the extent to which increased public coverage displaces private insurance.

Conclusion

We close with three general observations about uncompensated care in a post-ACA world. First, uncompensated care may decline as a result of coverage expansions, but it will not go away. Current projections suggest that there will still be roughly thirty million uninsured people in the United States in 2025.[23] As long as there are uninsured patients, hospitals will continue to provide uncompensated care. Additional uncompensated care will be attributable to insured patients with unaffordable out-of-pocket costs.

Second, policy makers have recently raised concerns about the level of charity care provided by not-for-profit,[24] and the regulatory environment is changing. Not-for-profit hospitals will face new and more stringent community benefit requirements under the ACA, beginning in 2016. These hospitals will be required to establish and publicize charity care policies and—before trying to collect patients’ unpaid medical bills—to take steps to inform those patients that they could be eligible for charity care.

Third, it is reasonable to conclude that the reduction in uncompensated care caused by Connecticut’s early Medicaid expansion represented a net gain for the state’s hospitals. However, it is less clear what reductions in uncompensated care might mean for other actors in the system. Some advocates of health care reform have argued that reductions in uncompensated care provided by hospitals will translate into lower prices for private payers, which in turn will lead to lower premiums.[25] This argument is predicated on an assumption that hospitals cost shift. Although research on cost shifting is limited, the best evidence from rigorous empirical studies suggests that it is not a widespread phenomenon.[26]

Studies examining how hospitals respond to exogenous changes in public program reimbursement as well as to other financial shocks suggest a number of ways that hospitals could use the savings from reduced uncompensated care. They could increase staffing levels,[27] increase investments in technology,[28] or increase their holdings of financial assets.[29] Disentangling the effect of a reduction in uncompensated care from other changes in hospital finances brought about by the ACA is a challenging but important objective for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Helen Levy received financial support from the National Institute on Aging (Grant No. NIA K01AG034232).

Footnotes

Results from this study were presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, San Diego, CA, May 1 2015.

Contributor Information

Sayeh Nikpay, Email: snikpay@umich.edu, Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and a visiting scholar in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Scholars Program at the University of California, Berkeley.

Thomas Buchmueller, Risk Management and Insurance in the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan.

Helen Levy, Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan.

Notes

- 1.Ollove M. Hospitals lobby hard for Medicaid expansion. [cited 2015 Apr 30];Stateline [blog on the Internet] 2013 Apr 17; Available from: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2013/04/17/hospitals-lobby-hard-for-medicaid-expansion. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation: State health facts: status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): KFF; 2015. Apr 29, [cited 2015 Apr 30]. Available from: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graves JA. Medicaid expansion opt-outs and uncompensated care. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2365–2367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1209450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price CC, Eibner C. For states that opt out of Medicaid expansion: 3.6 million fewer insured and $8.4 billion less in federal payments. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(6):1030–1036. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holahan J, Buettgens M, Dorn S. The cost of not expanding Medicaid [Internet] Washington (DC): Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2013. Jul 17, [cited 2015 Apr 30]. Available from: http://kff.org/medicaid/report/the-cost-of-not-expanding-medicaid/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLeire T, Joynt K, McDonald R. Impact of insurance expansion on hospital uncompensated care costs in 2014 [Internet] Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2014. Sep 24, [cited 2015 Apr 30]. (ASPE Issue Brief). Available from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2014/uncompensatedcare/ib_uncompensatedcare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garthwaite C, Gross T, Notowidigdo MJ. [cited 2015 Apr 30];Hospitals as insurers of last resort [Internet] 2015 Jan; Unpublished paper. Available from: http://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/noto/research/GGN_Hospitals%20as%20Insurers%20of%20Last%20Resort_jan2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arrieta A. The impact of the Massachusetts health care reform on unpaid medical bills. Inquiry. 2013;50(3):165–176. doi: 10.1177/0046958013516580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sommers BD, Arntson E, Kenney GM, Epstein AM. Lessons from early Medicaid expansions under health reform: interviews with Medicaid officials. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(4) doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.04.a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.State of Connecticut Department of Social Services. Section 1115 demonstration draft waiver application to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Medicaid low-income adult coverage demonstration [Internet] Hartford (CT): The Department; [cited 2015 Apr 30]. Available from: http://www.ct.gov/dss/lib/dss/pdfs/1115waivernewjune.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker AL. Charter Oak health plan enrollment falls as premiums rise. [cited 2015 Apr 30];CT Mirror [serial on the Internet] 2011 Sep 9; Available from: http://ctmirrororg/2011/09/09/charter-oak-health-plan-enrollment-falls-premiums-rise/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sommers BD, Kenney GM, Epstein AM. New evidence on the Affordable Care Act: coverage impacts of early Medicaid expansions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(1):78–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Hospital Association. Uncompensated hospital care cost fact sheet [Internet] Chicago (IL): AHA; 2014. Jan, [cited 2015 May 1]. Available from: www.aha.org/content/14/14uncompensatedcare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 15.Kane NM, Magnus SA. The Medicare cost report and the limits of hospital accountability: improving financial accounting data. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2001;26(1):81–105. doi: 10.1215/03616878-26-1-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Hospital Association. Fast facts on US hospitals [Internet] Chicago (IL): AHA; [updated 2015 Jan; cited 2015 May 1]. Available from: http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/fast-facts.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Government Accountability Office. Nonprofit, for-profit, and government hospitals: uncompensated care and other community benefits [Internet] Washington (DC): GAO; 2005. May 26, [cited 2015 May 1]. (Report No. GAO-05-743T). Available from: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d05743t.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, et al. The Oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year. Q J Econ. 2012;127(3):1057–1106. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hancock J. More high-deductible plan members can’t pay hospital bills. [cited 2015 May 1];Kaiser Health News [serial on the Internet] 2013 Aug 12; Available from: http://kaiserhealthnews.org/news/more-high-deductible-plan-members-cant-pay-hospital-bills/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowe J. Uncompensated care an ominous trend. [cited 2015 May 1];Healthcare Finance [serial on the Internet] 2011 Jun 2; Available from: http://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/uncompensated-care-ominous-trend. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karash JA. Bad debt. The rising tide of uncompensated care. Hosp Health Netw. 2010;84(2):11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buettgens M. Health Insurance Policy Simulation Model (HIPSM) methodology documentation [Internet] Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2011. Dec 21, [cited 2015 May 1]. (Research Report). Available from: http://www.urban.org/research/publication/health-insurance-policy-simulation-model-hipsm-methodology-documentation. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Congressional Budget Office. Insurance coverage provisions of the Affordable Care Act—CBO’s April 2014 baseline [Internet] Washington (DC): CBO; [cited 2015 May 1]. Available from: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43900-2014-04-ACAtables2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grassley C. Letter to Mosaic Life Care [Internet] Washington (DC): Senate Committee on the Judiary; 2015. Jan 16, [cited 2015 May 1]. Available from: http://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1503959-grassley-letter-2015-01-16-ceg-tomosaic.html. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoll K, Bailey K. Hidden health tax: Americans pay a premium [Internet] Washington (DC): Families USA; 2009. May, [cited 2015 May 1]. Available from: http://familiesusa.org/sites/default/files/product_documents/hidden-health-tax.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frakt AB. How much do hospitals cost shift? A review of the evidence. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):90–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White C, Wu VY. How do hospitals cope with sustained slow growth in Medicare prices? Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1):11–31. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Ody C. The impact of the 2008 stock market crash [Internet] Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. Feb, [cited 2015 May 1]. How do hospitals respond to negative financial shocks? (NBER Working Paper No. 18853). Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w18853. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duggan MG. Hospital ownership and public medical spending. Q J Econ. 2000;115(4):1343–1373. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.