Abstract

The majority of medical providers, nurses, and patients agree that appearance is important for patient care. However, at our institution, concerns regarding providers’ white coats as fomites are expressed primarily by providers and nurses, not by patients. We provide a framework for approaching this important issue through a structured quality-improvement process.

Keywords: White coat, Physician attire, Infection control, Hand hygiene, Quality improvement

Health care-associated infections are a significant source of mortality and morbidity. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 1 in 20 inpatients will acquire a health careassociated infection.1 Although there is strong consensus regarding the importance of health care worker hand hygiene, debate remains regarding the role of health care worker attire in infection prevention. Research has shown that white coats do become rapidly saturated with potentially pathogenic microorganisms when worn in a hospital2; however, despite concerning stories in the lay press and online,3–5 there are minimal data demonstrating that pathogens are spread to patients via attire.6

Given this lack of hard evidence, what do patients, doctors, and nurses believe about provider attire? Data on patient attitudes toward provider attire in the United States are sparse. One US study7 reported that physicians wearing white coats favorably influenced trust and increased confidence during the medical encounter. Provider and nurse attitudes toward attire are even scarcer. A recent study from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America8 revealed that patients generally did not perceive white coats as infection risks. In our effort to formulate a rational health care worker dress code that balances patient safety with acceptability, it was important to understand all stakeholder perceptions of provider attire. The goal of our project was to assess current provider, nurse, and patient attitudes regarding provider attire.

METHODS

Our study was performed on inpatient medicine and surgery units at University of Washington Medical Center and Harborview Medical Center during 2012. The primary intent was to assess perceptions of medical provider attire as part of a quality improvement initiative. Thus, institutional review board approval was not required.

Electronic surveys were distributed to nurses and medical providers without exclusion at both medical centers. Paper copies of a similar questionnaire were distributed to patients at the time of hospital discharge. Exclusion criteria for patients included being unable to read or speak English, too ill to participate, younger than age 18 years, or having cognitive impairment, behavioral issues, or severe mental illness. Identical questionnaires were distributed to patients and nurses, and included 13-items using a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) with 2 yes/no questions about respondents voicing concerns or their intent to do so, and additional space for comments. The questionnaires distributed to medical providers were homologous to those presented to nurses and patients with 3 additional questions regarding frequency of wearing white coats. These questionnaires are available from the authors upon request.

Responses to collapsed categories on the 5-point Likert scale are presented as percentages. P values for the comparison of groups on percentages were calculated by χ2 test. Calculations were carried out in R version 2.15.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

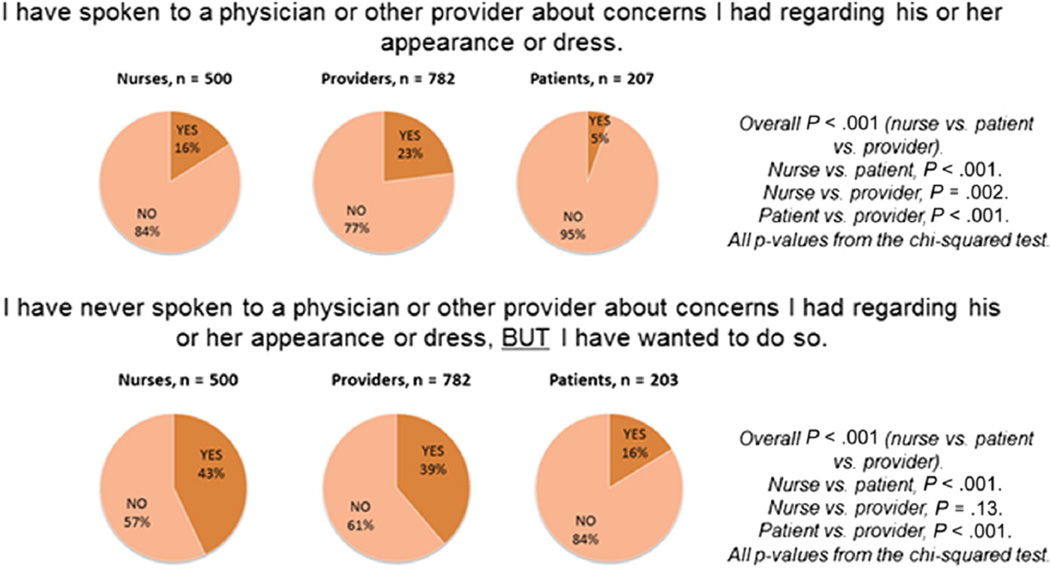

The questionnaire was completed by 782 medical providers (39% at University of Washington Medical Center and 17% at Harborview Medical Center; 44% residents/fellows at both institutions), 500 nurses (50% University of Washington Medical Center and 50% Harborview Medical Center), and 212 patients (53% University of Washington Medical Center and 47% Harborview Medical Center) (see Fig. 1). Ninety-five percent of providers and 93% of nurses agreed that appearance was important for patient care, versus 83% of patients (P < .001). Of the medical providers, 42% wore a white coat when examining patients. White coats were laundered at least monthly by 56% of providers, and 43% were embarrassed by the appearance of their white coat. When asked if white coats were “unhygienic,” 53% of providers and 51% of nurses agreed, compared with only 6% of patients (P <.001). In addition to white coats, long neckties were also identified as unhygienic by the health care workers (62% of nurses and 58% of providers, versus 31% of patients; P < .001). Notable themes emerged around professionalism, propriety, and identification (Table 1). Lastly, 2 yes/no questions were asked of all respondents (Fig. 2).

Fig 1.

Results from questionnaires.

Table 1.

Select comments from questionnaires

| Responder | Hygiene | Professionalism/propriety | Identifying providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Providers | “Some [white coats] that I have seen on others have been embarrassing, with old stains, etc.” “Ties and white coats may clearly serve as reservoirs for MDROs and may potentially be vectors for nosocomial transmission.” |

“…Jeans, quasijeans, wrinkled/baggy/worn out clothing, and other subbusiness-casual attire does not project professionalism…” “My bigger concern is really, really short skirts or visible cleavage in women…” |

“In the hospital, the white coat helps identify me as a doctor to both staff and patients.” “…I think the white coat also helps the patients sort out who I am. ” |

| Nurses | [White coats] do seem to be unhygienic…my guess is they are rarely [if] EVER washed.” “…I am most concerned with the infection control issues that may arrive when MDs wear long white coats and examine patients.” |

“Female physicians should never wear high heels or show cleavage…it’s absolutely inappropriate.” “Jeans and cargo pants are being worn by physicians…. Some of our patients are better dressed than the providers are.” |

“Physicians should be easily identifiable…ID cards all look the same at 6 ft with less than perfect vision…” “…White coat is a must in establishing rank.” |

| Patients | “I trust that physicians wear what is most appropriate and hygienic for me.” “No correlation between color [of] a physician’s coat and their hygiene practices.” |

“For the most part, these people are professionals and they should know they need to look that way.” “People in the medical field should dress professionally, no street clothes, nothing provocative.” |

“Wearing a white coat with a name tag lets us know we are talking to a doctor and his/her name.” “I like the ability to identify a doctor by clothing standard, it leaves no doubt [to] who you are addressing.” |

MD, medical doctor; MDRO, multidrug-resistant organisms.

Fig 2.

Concerns and discussion about medical provider appearance.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that the conversation regarding white coats remains pertinent and appearance is important to all stakeholders. However, providers and nurses expressed significantly different attitudes toward attire-related hygiene than did patients. Clinicians indicated that unclean provider attire may play a role in pathogen transmission. This was in stark contrast to patients, who were much less likely to express such concerns. This finding mirrored the results of a Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America study.8

Although attire hygiene was the focus of our survey, themes emerged around professionalism, propriety, and identification. These concurrent themes are also supported in the literature; studies show patients have the most confidence in physicians wearing white coats, and this is associated with increased perception of provider competency as well as the ability of patients to identify their provider.7–10 Given these findings, factors beyond infection risk should be considered when modifying dress codes.

Finally, our study revealed a hesitation to vocalize concerns about provider attire. Whereas a minority of providers, nurses, and patients reported having approached providers when they had concerns about their appearance, many more wanted to but chose not to directly discuss the issue with the relevant provider. This suggests that a culture shift or formal communication rubric might be necessary to allow providers and nurses to voice concerns about attire. Current evidence has yet to clarify the causal relationship between attire and health care-associated infection.2,5,8 Our study results suggest that many health care providers believe that there may be a link; therefore, we propose a structured process for discussion and implementation of patient safety initiatives around attire hygiene (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Model for discussing and addressing issues related to provider attire.

Limitations of our study include the subjective nature of this topic, preformed answer choices rather than structured interviews, and participants’ opinions possibly not representing opinions of the population outside of the research setting.

It may be impractical to determine exactly how cross-contamination occurs with provider attire. Instead, we have chosen to focus on provider and patient satisfaction. We believe that patients should know who their providers are, that providers should have the option of wearing attire that fulfills their desire to maintain a hygienic and “professional” appearance, and that all stakeholders should be empowered to voice their concerns. Achieving this balance will create a culture of provider autonomy, patient satisfaction, and overall safety.

Acknowledgments

Financial support included the University of Washington Patient Safety Innovations Program.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-associated infections. [Accessed July 31, 2013]; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/surveillance/index.html.

- 2.Burden M, Cervantes L, Weed D, Keniston A, Price CS, Albert RK. Newly Cleaned physician uniforms and Infrequently Washed White Coats have similar Rates of Bacterial contamination after an 8-Hour Workday: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2011;6:177–182. doi: 10.1002/jhm.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy C. End for traditional doctor’s coat. [Accessed 19 June 2008];BBC News. 2007 Sep 17; http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/health/6998195.stm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray S. Superbug fears kill off doctors’ white coats. The Times. 2007 Sep 17; http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/health/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson JA, Loveday HP, Hoffman PN, Pratt RJ. Uniform: an evidence review of the microbiological significance of uniforms and uniform policy in the prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2007;66:e301–e307. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.RID: Committee to Reduce Infection Deaths. [Accessed July 31, 2013]; Available at: http://www.hospitalinfection.org. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, Kilpatrick AO. What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118:1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S, Mayer J, Munoz-Price LS, Murthy R, et al. Healthcare Personnel attire in Non-Operating Room settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:107–121. doi: 10.1086/675066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, Crossley M. Are we dressed to impress? A descriptive survey assessing patients’ preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clinical Medicine. 2009;9:519–524. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.9-6-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clement R. Is it time for an evidence based uniform for doctors? BMJ. 2012;345:e8286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]