Abstract

Phosphatase enzymes are responsible for much of the recycling of organic phosphorus in soils. The PhoD alkaline phosphatase takes part in this process by hydrolyzing a range of organic phosphoesters. We analyzed the taxonomic and environmental distribution of phoD genes using whole-genome and metagenome databases. phoD alkaline phosphatase was found to be spread across 20 bacterial phyla and was ubiquitous in the environment, with the greatest abundance in soil. To study the great diversity of phoD, we developed a new set of primers which targets phoD genes in soil. The primer set was validated by 454 sequencing of six soils collected from two continents with different climates and soil properties and was compared to previously published primers. Up to 685 different phoD operational taxonomic units were found in each soil, which was 7 times higher than with previously published primers. The new primers amplified sequences belonging to 13 phyla, including 71 families. The most prevalent phoD genes identified in these soils were affiliated with the orders Actinomycetales (13 to 35%), Bacillales (1 to 29%), Gloeobacterales (1 to 18%), Rhizobiales (18 to 27%), and Pseudomonadales (0 to 22%). The primers also amplified phoD genes from additional orders, including Burkholderiales, Caulobacterales, Deinococcales, Planctomycetales, and Xanthomonadales, which represented the major differences in phoD composition between samples, highlighting the singularity of each community. Additionally, the phoD bacterial community structure was strongly related to soil pH, which varied between 4.2 and 6.8. These primers reveal the diversity of phoD in soil and represent a valuable tool for the study of phoD alkaline phosphatase in environmental samples.

INTRODUCTION

Phosphorus (P) is an essential macronutrient for all living cells (1). Despite its relative abundance in soils, P is one of the main limiting nutrients for terrestrial organisms (2). P is present in organic and inorganic forms in soil, but only the inorganic orthophosphate ions in soil solutions are readily available for plants (3). To sustain crop productivity, large amounts of P fertilizers are therefore used in agriculture, both as inorganic fertilizers (e.g., triple super phosphate) and organic fertilizers (e.g., manure). After application, some of the inorganic P is rapidly taken up by plants and microorganisms, while the remaining P is immobilized as insoluble and bound P forms in the soil. Microorganisms can access and recycle P from these recalcitrant P forms by solubilization of inorganic P and by mineralization of organic P via enzymatic processes mediated primarily by phosphatases, which hydrolyze the orthophosphate group from organic compounds (3). When facing P scarcity, microorganisms upregulate expression of functional genes coding for phosphatases (phosphomonoesterases, phosphodiesterases, phytases), high-affinity phosphate transporters, and enzymes for phosphonate utilization, which together constitute the Pho regulon (4). The phosphomonoesters which are hydrolyzed by phosphatases are generally the dominant fraction of organic P and can represent up to 90% of the organic P in soil (3).

Prokaryotic alkaline phosphatases have been grouped into three distinct families, PhoA, PhoD, and PhoX (5–7), which are classified in COG1785, COG3540, and COG3211, respectively, of the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) categorization. PhoA was the first alkaline phosphatase to be characterized. It is a homodimeric enzyme that hydrolyzes phosphomonoesters and is activated by Mg2+ and Zn2+ (7). PhoD and PhoX are monomeric enzymes that hydrolyze both phosphomonoesters and phosphodiesters and are activated by Ca2+ (5, 6). Enzymes of all three families are predominantly periplasmic, membrane bound, or extracellular (8). PhoD and PhoX are exported by the twin-arginine translocation pathway (5, 6), while PhoA is secreted via the Sec protein translocation pathway (9). There is high sequence variability in the PhoA, PhoD, and PhoX proteins, not only between the families but also within each family (5, 9). PhoD is widespread in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (8, 10).

Until recently, our knowledge of the phosphatase-encoding genes in prokaryotes was based on traditional culture-dependent methods. Advances in culture-independent techniques have provided new tools for the study of microbial communities in the environment. The first functional gene probes to target alkaline phosphatase genes were the primers developed by Sakurai et al. named ALPS primers (11). They were based on phosphatase gene sequences from seven isolates and first used to examine the different soil alkaline phosphatase community structures resulting from mineral and organic fertilization. Alkaline phosphatase genes belonging to the Actinobacteria, Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria, and Cyanobacteria classes were identified by cloning, giving the first insight into alkaline phosphatase diversity in soil (11).

Subsequently, the ALPS primers were demonstrated to be specific to the phoD alkaline phosphatase gene (10). They were used to assess alkaline phosphatase gene diversity and structure in several soils by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) (12–15) and by 454 sequencing (10, 16). These studies showed that crop management, application of organic and conventional fertilizers, and vegetation all affect the phoD alkaline phosphatase gene diversity. Tan et al. (10) examined the effects of three mineral P fertilization intensities (zero, medium, and high input) in grassland soil on the composition and diversity of alkaline phosphatase and found a change in the phoD bacterial community compositions between unfertilized and fertilized treatments, with the dominant phoD alkaline phosphatase genes affiliated with Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Cyanobacteria. However, they pointed out that the ALPS primers are likely to have an amplification bias, resulting in an overrepresentation of Alphaproteobacteria, and that new primers are therefore required to provide better coverage of the phoD diversity.

In this study, we assessed the diversity and environmental distribution of the phoD gene based on current genome and metagenome databases, and we present a new set of improved primers which targets the large diversity of phoD genes in soil microorganisms. These primers can be used as a tool both to identify PhoD-producing bacteria and to study phoD bacterial community diversity and composition in the environment. The newly designed primers were tested in a gene-targeted metagenomic approach using 454 sequencing in a range of soils collected from two continents with different climates and soil properties. Finally, we compared them to the previously published ALPS primers (11), using the same samples and methodology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Taxonomic and environmental distribution of phoD alkaline phosphatase genes across microbial genomes and metagenomes.

The distribution of phoD genes was assessed using the Integrated Microbial Genomes and Metagenomes (IMG/M) database, a dedicated system for annotation of whole genomes and metagenomes (17). Draft and complete genome data sets were used to evaluate the distribution of phoD across kingdoms and phyla, and metagenome data sets were used to evaluate the prevalence of phoD in the environment (data accessed on 13 July 2015). Metagenome data sets were categorized as “air,” “engineered and waste” (bioreactor and waste treatment), “extreme environments” (saline, alkaline, hot spring, brine, and black smokers), “fresh water,” “marine environment,” “plant-associated” (leaves and wood), “animal-associated” (associated with humans, arthropods, molluscs, and sponges), and “soil” (rhizosphere and bulk soil). These categories were chosen based on the environment-type classification of the IMG/M database. The relative abundance of phoD gene counts per environment type was calculated as the gene count number normalized by the total number of bases sequenced per metagenome data set.

Soil sampling and general soil characteristics.

Four grassland soils were collected in Australia in July 2013 (samples 1 to 4 [S1 to S4]), and two grassland soils were sampled in Switzerland in September 2012 (S5 and S6) (Table 1). These represent a broad range of soil types, vegetation, and climatic conditions, varying from hot semiarid to continental temperate climates. At each site, five soil cores from the top 5 cm were randomly collected and homogenized by sieving (4 mm). A subsample was stored at −80°C for molecular analysis. The remaining composite soil was air dried and used to determine the basic soil properties, including pH, texture, and total carbon (C) and P. Methods used to determine the soil properties are described in Table 1. The sampled soils covered a range of textures, with clay contents varying between 12 and 38%. Soil pH ranged between 4.2 and 6.8. Total C varied between 5 and 34 g kg−1 soil, and total P varied between 193 and 705 mg kg−1 soil. The vegetation densities were similar at sampling sites S5 and S6 but very different at the other sites, ranging from dense to scarce, depending on the location.

TABLE 1.

Description of the grassland soils S1 to S6, with location, geographical coordinates, climate, soil type, vegetation, pH, texture, and total C and P

| Sample | Site | Geographical coordinates | Climate (climate category)a | Soil typeb | Vegetation | pH (CaCl2)c | Texture (% clay, % silt, % sand)d | Total C (g kg−1 soil)e | Total P (mg kg−1 soil)f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Kia-Ora (Australia) | 34°48′18″S, 148°35′00″E | Warm temperate climate, fully humid with warm summer (Cfb) | Planosol | Microlaena stipoides, Austrodanthonia spp., Elymus scaber, Bothriochloa macra, Austrostipa spp. | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 14, 28, 58 | 21.0 ± 0.8 | 221 ± 8 |

| S2 | Narrabri (Australia) | 30°15′14″S, 149°51′53″E | Warm temperate climate, fully humid with warm summer or with hot summer (Cfa) | Planosol | Chrysocephalum sp., Themeda sp., Festuca arundinacea | 6.1 ± 0.0 | 38, 27, 35 | 23.7 ± 0.1 | 705 ± 13 |

| S3 | Nyngan (Australia) | 31°25′52″S, 147°04′09″E | Arid climate, hot steppe (BSh) | Cambisol | Mixed grasses and dicot plants; clumpy cover, not a sward | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 30, 33, 37 | 15.0 ± 0.3 | 466 ± 10 |

| S4 | Mutawintji (Australia) | 31°16′19″S, 142°17′44″E | Arid climate, hot steppe (BSh) | Leptosol | Chenopodium sp., Acacia sp., Astrebla sp. | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 12, 11, 77 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 193 ± 11 |

| S5 | Watt (Switzerland) | 47°25′45″N, 008°29′31″E | Warm temperate climate, fully humid with warm summer (Cfb) | Cambisol | Arrhenaterion elatioris | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 30, 33, 37 | 27.5 ± 0.1 | 613 ± 33 |

| S6 | Watt (Switzerland) | 47°25′45″N, 008°29′31″E | Warm temperate climate, fully humid with warm summer (Cfb) | Cambisol | Arrhenaterion elatioris | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 30, 33, 37 | 34.4 ± 0.4 | 703 ± 39 |

Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Climate categories are described further in a paper by Kottek et al. (51).

World Reference Base for Soil Resources (52).

Measured in a soil suspension in 0.01 M CaCl2 with a 1:2.5 mass/volume ratio using a Benchtop pH/ISE 720A (Orion Research Inc., Jacksonville, FL).

Determined by a commercial soil analysis lab (Soil Conseil, Nyon, Switzerland).

Measured on dry and ground soil using a CNS analyzer (Thermo-Finnigan).

DNA extraction from soil.

All DNA samples were extracted in duplicate. Nucleic acids were extracted from the Australian samples using a DNA PowerSoil isolation kit (Mo Bio, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions, with an initial bead-beating step of 2 cycles of 3 min at 30 Hz using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen, CA). Nucleic acids were extracted from the Swiss samples (2 g of frozen soil) using an RNA PowerSoil isolation kit (Mo Bio) according to the manufacturer's instructions, with an additional homogenizing step using an Omni Bead Ruptor homogenizer (Omni International, Kennesaw, GA) (2.8-mm zirconium beads for 1 min at 5 m s−1) prior to isolation. DNA was eluted from the RNA/DNA capture column using 4 ml of DNA elution solution (1 M NaCl, 50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS], 15% isopropanol [pH 7]). DNA was precipitated using isopropanol and resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated H2O. Only the DNA extracts were used in this study.

Primer design and in silico testing.

Gene sequences annotated as phoD and/or associated with COG3540 (Clusters of Orthologous Groups; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/), which corresponds to phoD alkaline phosphatase, were retrieved from the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) and UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) databases. They were then clustered at 97% similarity using CD-HIT (18), resulting in a total of 315 sequences used as references for the primer design (see the list in Table S1 and the taxonomic tree in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The reference sequences were affiliated with 11 phyla, including Actinobacteria (59 sequences), Bacteroidetes (22 sequences), Cyanobacteria (22 sequences), Deinococcus-Thermus (2 sequences), Ignavibacteriae (1 sequence), Firmicutes (13 sequences), Gemmatimonadetes (1 sequence), Spirochaetes (16 sequences), Planctomycetes (4 sequences), Proteobacteria (173 sequences), and Verrucomicrobia (2 sequences).

The gene sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (19), and the alignment was manually reviewed by comparison with the aligned translated sequences, using Geneious 6.1.2 (Biomatters, Australia) and the alignment of the COG3540 group available on the NCBI website (Conserved Domain Protein Family, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml) as the amino acid reference alignment. The most suitable conserved regions for primer design were identified using PrimerProspector (20). Forward and reverse candidate primers were then manually designed to reach the maximum coverage of the reference sequences. Candidate primers were paired to target an amplicon length of 250 to 500 bp, which represents the best compromise length for next-generation sequencing and quantitative PCR studies. They were then tested in silico using De-MetaST-BLAST (21) to identify potential primer pairs with an appropriate product size and coverage of the reference sequences.

Optimization and validation of phoD-targeting primers.

Candidate primers (21 forward primers and 23 reverse primers) were tested in a gradient PCR using a mixture of soil genomic DNA (S5 and S6) (Table 1) as the template. PCRs were performed in a 25-μl volume containing 1× MyTaq reaction buffer (including MgCl2 and deoxynucleoside triphosphates [dNTPs]), 0.5 μM each primer, and 0.6 U of MyTaq polymerase (Bioline, NSW, Australia) with 1 to 2 ng DNA as the template in an S1000 thermocycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA). The amplification reaction included an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of a denaturation step of 30 s at 95°C and an annealing step of 30 s at the calculated annealing temperature of each candidate primer pair (gradient of ±3°C), and an extension step of 30 s at 72°C. A final extension step was performed for 5 min at 72°C. Amplicon size and intensity and the presence of primer dimers were assessed visually after electrophoresis on a 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel and staining with ethidium bromide.

The amplicon specificity was evaluated for selected primer pairs by cloning and sequencing. The PCR products were ligated at 4°C overnight using pGEM-T vector systems (Promega, Madison, WI) and transformed into chemically competent E. coli cells [α-select; F− deoR endA1 recA1 relA1 gyrA96 hsdR17 (rk− mk+) supE44 thi-1 phoA Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 Φ80lacZΔM15 λ−] according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bioline). Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) profiling of clones with the expected insert size was done using HhaI (0.2 U/μl for 3 h at 37°C; Promega), and profiles were visualized by electrophoresis on a 2% (wt/vol) agarose gel. Representative inserts of unique RFLP profiles were then sequenced (Macrogen Inc., Seoul, South Korea). The resulting sequences were used to evaluate the coverage and specificity of the candidate primer pairs using BLAST (22).

Amplicon diversity was examined for three candidate primer pairs by 454 GS-FLX+ sequencing (Roche 454 Life Sciences, Branford, CT) using barcoded primers. The barcoded primer design, sequencing, and initial quality filtering were performed by Research and Testing Laboratory (Lubbock, TX) using standard protocols. Briefly, sequences with a quality score of <25 were trimmed, and chimeras were removed using USEARCH, with clustering at a 4% divergence (23). Denoising was performed with the Research and Testing Denoise algorithm, which uses the nonchimeric sequences and the quality scores to create consensus clusters from aligned sequences. Within each cluster, the probability of prevalence of each nucleotide was calculated, and a quality score was generated, which was then used to remove noise from the data set.

The primer pair phoD-F733 (5′-TGGGAYGATCAYGARGT-3′)/phoD-R1083 (5′-CTGSGCSAKSACRTTCCA-3′) provided the highest phoD diversity and coverage (numbers indicate the respective positions in the reference phoD gene of Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099). phoD-F733 anneals to the conserved region that consists of the amino acid residues WDDHE, which contribute to the coordination of two Ca2+ cofactors (24). In addition, the fragment targeted by phoD-F733/phoD-R18083 includes two conserved arginine residues. Nevertheless, the variable part of the amplified region also allows a good identification of taxonomy. This primer pair was named PHOD and used further in this study.

454 sequencing using PHOD and ALPS primers.

For comparative analysis of PHOD and ALPS primers ALPS-F730/ALPS-R110 (5′-CAGTGGGACGACCACGAGGT-3′/5′-GAGGCCGATCGGCATGTCG-3′) (11), phoD genes were amplified in pooled duplicate DNA extracts at a concentration of 20 ng μl−1 using the PCR conditions described above, with an annealing temperature at 58°C for PHOD primers and at 57°C for ALPS primers. Samples were then sequenced using 454 GS-FLX+ pyrosequencing (Roche) by Research and Testing Laboratory, with a resulting yield between 1,642 and 13,998 reads per library.

Sequence analysis.

Sequencing data sets amplified by PHOD and ALPS primers were analyzed separately using mothur (25). Sequences were analyzed as nucleic acid sequences to keep the maximum information, allow accurate identification, and avoid artifacts due to frameshifts and errors during back-translation (26). After demultiplexing, reads containing ambiguities and mismatches with either the specific primers or the barcode were removed. Reads with an average quality score of <20 were then filtered out. The remaining reads were trimmed at 150 bp and 450 bp as the minimum and maximum lengths, respectively. Across all samples, 92% of the sequences had a length between 320 and 380 bp.

The resulting PHOD- and ALPS-amplified data sets were merged and aligned using the Needleman-Wunsch global alignment algorithm as implemented in mothur, using 6-mer searching and the aligned reference sequences as the template. The pairwise distance matrix was calculated from the alignment, and sequences were clustered using the k-furthest method as implemented in mothur, with a similarity cutoff at 75% to define the operational taxonomic units (OTUs), as calculated by Tan et al. (10). OTU matrices were normalized to the smallest library size using the normalized.shared command in mothur to allow comparison between samples. The relative abundance of each OTU was normalized by the total number of reads per sample. The normalized values were then rounded to the nearest integer. The taxonomy assignment was performed using BLASTn in BLAST+ (27), with a minimum E value of 1e−8 to retrieve NCBI sequence identifiers (GI accession number). Subsequently, in-house Perl scripts were used to populate and query a MYSQL database containing the NCBI GI number and taxonomic lineage information (the scripts were written by Stefan Zoller, Genetic Diversity Centre, ETH Zurich, and are available on request).

Data analysis.

Rarefaction curves were calculated and extrapolated to 5,000 reads to standardize the samples using EstimateS (version 9; http://purl.oclc.org/estimates). The unconditional variance was used to construct 95% confidence intervals for both interpolated and extrapolated values, which assumes that the reference sample represents a fraction of a larger but unmeasured community. Observed species richness (Sobs) based on the normalized library size, estimated species richness based on a library size of 5,000 reads (Sest), and the Chao1 species richness index (28) were calculated using EstimateS. Additionally, the Good's coverage (29) and the alpha diversity estimated by the Shannon-Wiener (H′) (30) index were calculated. Paired Student t tests were used to compare Sobs, Sest, Good's coverage, and H′ indices between samples.

Similarities between phoD bacterial community structures were tested using pairwise libshuff analysis as implemented in mothur with 1,000 iterations (31). Correlations between the community composition and environmental variables were tested by redundancy analysis (RDA), followed by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the RDA fit, and a variance partitioning analysis using the vegan package (vegan; Community Ecology Package, R package version 2.2-0; http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan) in R version 2.15.0 (R Core Team, 2014; http://www.R-project.org). Prior to analysis, the measured environmental variables (clay and silt content, total C and P, and soil pH) were standardized using the Z-score method, and nominal variables (vegetation, climate, and soil type) were also included.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The standard flowgram format (.sff) files were submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the accession number ERP008947.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Taxonomic distribution of phoD alkaline phosphatase gene.

Our current knowledge of the taxonomic distribution of phoD was described based on the IMG/M database. A total of 63 archaeal, 6,469 bacterial, and 73 eukaryotic draft or complete genomes containing at least one copy of the phoD gene were found.

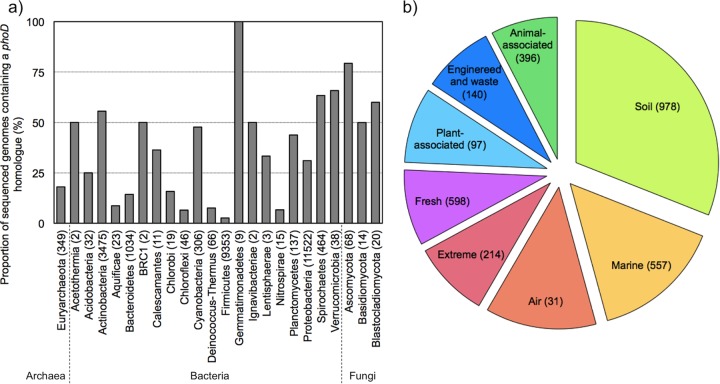

In bacteria, the phoD gene was spread across 20 phyla (Fig. 1a). More than half of the genomes of Actinobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Spirochaetes, and Verrucomicrobia contained at least one copy of the phoD gene. Among the Proteobacteria, the phoD gene occurred in 52, 30, and 34% of the Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria, respectively. The number of phoD copies per genome varied between 1 and 9, but the majority of sequenced genomes (71%) carried only a single copy.

FIG 1.

Current knowledge of the phoD gene in the IMG/M database. (a) Proportion of sequenced genomes containing a phoD homologue. The numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of sequenced genomes in each phylum. (b) Relative abundance of phoD genes in different types of environments (normalized as the number of phoD counts per number of bases sequenced per metagenome data set). The numbers in brackets indicate the number of metagenome data sets per environment type.

Although phoD is widespread across the bacterial phyla, it is important to note that the microbial genome sequence database contains the genomes of cultured strains almost exclusively, which creates a general bias in databases (32). Proteobacteria was the most recurrent phylum in the database, as the Gammaproteobacteria and more particularly the Pseudomonas genus are among the most intensively studied taxa (32) and thus are the genomes found most frequently in databases. Given the presence of the phoD gene in the less represented phyla, such as Chloroflexi, Deinococcus-Thermus, and Planctomycetes, phoD-targeting primers represent an important tool to study these less easily culturable phyla.

Additionally, phoD genes were found in archaea, affiliated almost entirely with Euryarchaeota (Halobacteriaceae), and in eukaryotes, mainly in Ascomycetes. Alkaline phosphatase activity in archaea has only rarely been reported, e.g., from extreme environments (33, 34), while in eukaryotes it has been reported in Basidiomycetes (35) and in eukaryotic phytoplanktonic cells (36); in mammals, it is widely used as an indicator for liver disease (37). However, alkaline phosphatase activity has not previously been associated with the phoD gene in these taxa.

Environmental distribution of phoD alkaline phosphatase—a meta-analysis.

The prevalence of phoD in the environment was investigated by analysis of 3,011 available metagenome data sets in the IMG/M database. The phoD gene was found in a range of environments (Fig. 1b), with the greatest abundance in soil, followed by marine and air environments.

Metagenomic studies focusing on phosphatases in marine environments have shown that phoD and phoX are more common than phoA in these samples (8, 38). The high diversity and relative abundance of the phoD gene found in soil metagenomes (Fig. 1b) suggest that phoD may also be particularly relevant in terrestrial ecosystems, although the relative abundances of the three alkaline phosphatase families in soil have not yet been studied on the metagenome level. The fact that organic P represents between 30% and 80% of the total P in grassland and agricultural soils, mainly in the form of diverse phosphomonoesters and diesters (3), may promote the diversity of phoD in terrestrial ecosystems.

Performance of PHOD and ALPS primers.

A key aim of this work was to design a new set of PHOD primers targeting the bacterial phoD alkaline phosphatase for studying the phoD bacterial community diversity and composition in soil. The PHOD primers were tested on six soils that represent a range of contrasting soil properties, collected in Australia and Switzerland, and the results were compared with those obtained with the same samples using the ALPS primers.

Generally, amplification using PHOD primers resulted in fewer filtered reads than that with ALPS primers, with 2,309 ± 1,148 (mean ± standard deviation) and 7,778 ± 3,107 reads and average read lengths of 380 ± 33 bp and 364 ± 35 bp for PHOD- and ALPS-amplified samples, respectively (Table 2). The difference in the number of filtered reads per library was directly linked to primer design, more particularly to the degree of degeneracy of the PHOD primers. Increasing degeneracy in primers generally reduces PCR efficiency due to the dilution of each unique primer sequence (39). Degenerate primers increase the risk of unspecific annealing during the PCR but increase the probability of amplifying yet-unknown phoD gene sequences by allowing all coding possibilities for an amino acid residue in the nucleic acid sequences (40). When used appropriately, degenerate primers, such as the PHOD primers, represent a great advantage in studies on genetic diversity by targeting known and unknown sequences in environmental samples (41).

TABLE 2.

Data obtained with PHOD and ALPS primers based on normalized dataa

| Primer | Sample | No. of filtered reads | No. of unique reads | No. of reads after normalization | Species richness index |

Good's coverage | H′ | No. of: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sobs | Sest | Chao1 | Phyla | Classes | Orders | Families | Genera | |||||||

| PHOD | S1 | 1,915 | 1,763 | 1,088 | 290 | 685 | 684 | 0.83 | 4.6 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 37 |

| S2 | 2,170 | 1,820 | 963 | 201 | 293 | 303 | 0.91 | 3.9 | 10 | 14 | 18 | 29 | 39 | |

| S3 | 3,090 | 2,709 | 1,001 | 227 | 458 | 452 | 0.87 | 4.2 | 9 | 14 | 18 | 32 | 43 | |

| S4 | 1,042 | 829 | 1,037 | 148 | 214 | 210 | 0.93 | 3.8 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 20 | 23 | |

| S5 | 4,399 | 3,296 | 977 | 191 | 359 | 352 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 11 | 16 | 21 | 37 | 46 | |

| S6 | 1,240 | 937 | 1,039 | 199 | 318 | 313 | 0.89 | 4.2 | 9 | 12 | 14 | 26 | 31 | |

| ALPS | S1 | 5,958 | 2,097 | 1,017 | 78 | 100 | 97 | 0.99 | 3.2 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 15 | 18 |

| S2 | 12,619 | 3,168 | 998 | 168 | 209 | 290 | 0.93 | 3.8 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 24 | 32 | |

| S3 | 3,730 | 1,276 | 1,027 | 139 | 217 | 212 | 0.95 | 3.8 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 18 | 21 | |

| S4 | 5,025 | 2,097 | 995 | 123 | 181 | 177 | 0.98 | 3.1 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 22 | 27 | |

| S5 | 9,482 | 3,110 | 1,012 | 107 | 143 | 140 | 0.97 | 3.4 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 14 | 18 | |

| S6 | 9,854 | 2,038 | 999 | 195 | 238 | 237 | 0.98 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 23 | 29 | |

| P value (Student's t test) | <0.05* | <0.05* | NS | <0.1* | <0.05* | <0.05* | <0.01* | <0.05* | <0.01* | <0.01* | <0.01* | <0.01* | <0.01* | |

Number of filtered reads (after initial processing), number of unique reads, and number of reads after normalization per library, species richness indices (Sobs, Sest, and Chao1), Good's coverage, alpha diversity (Shannon-Wiener index, H′), and taxonomy (numbers of phyla, classes, orders, families, and genera). *, statistically significant result; NS, nonsignificant.

By filtering out redundant sequences, the number of reads decreased remarkably in the ALPS-amplified samples, leading to more-similar numbers of unique reads for the two sets of primers, which averaged 1,893 ± 885 bp (mean ± standard deviation) and 2,297 ± 659 bp for PHOD- and ALPS-amplified samples, respectively. This showed that ALPS-amplified samples consisted of a greater number of redundant reads than did PHOD-amplified samples. Finally, normalization of the library size in order to compare the two primer sets resulted in an average library size of 1,013 ± 31 bp. Our results suggest that the ALPS primers target a narrow spectrum of sequences which represent a large fraction of the reads after amplification.

Species richness and alpha diversity of the phoD gene in six soils.

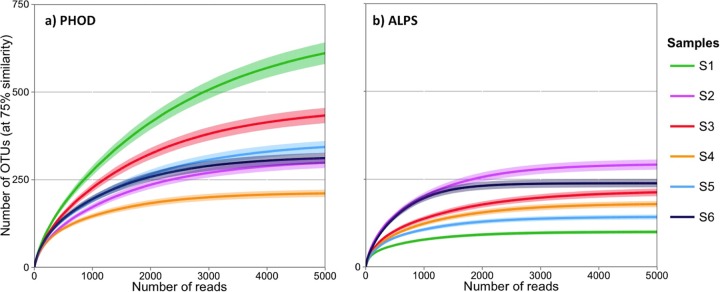

Amplification with PHOD primers revealed a 2-fold variation in species richness among the six samples (Table 2). Sobs was lowest in S4 and highest in S1, with 148 and 290 OTUs, respectively. Chao1 and Sest indices, derived from the rarefaction curves, showed a similar trend. The difference in species richness between samples is well illustrated by the rarefaction curves (Fig. 2a). The rarefaction curve of S1 had the steepest slope, showing the greatest increase of species with the number of reads, while that of S4 reached the asymptote with the fewest reads (ca. 3,000).

FIG 2.

Rarefaction curves of samples S1 to S6 amplified by PHOD (a) and ALPS (b) primers extrapolated to 5,000 reads with 95% confidence intervals.

Compared to amplification with PHOD primers, amplification with ALPS primers resulted in significantly lower species richness and alpha diversity (Table 2). In ALPS-amplified samples, the rarefaction curves always reached the asymptote with fewer reads than in the corresponding PHOD-amplified samples (Fig. 2a and b). The rarefaction curves of S1 when amplified using PHOD and ALPS primers contrasted particularly strongly, leading to a 7-fold difference in Chao1 and Sest. Likewise, H′ was always greater in PHOD- than in ALPS-amplified samples. This suggests that PHOD primers target a broader diversity of phoD-bearing bacteria than ALPS primers.

Using ALPS primers, Tan et al. (10) found between 450 and 548 OTUs in soils fertilized with zero, medium, or high P input, with a sequencing depth between 14,279 and 16,140 reads. In contrast, Fraser et al. (16) reported lower numbers, which are in the same range as in the six soils analyzed in this study. They found between 137 and 163 OTUs in soils from organic and conventional cropping systems and prairie, with a sequencing depth of 11,537 to 54,468 reads. Thus, the number of OTUs seems to be quite variable between studies and/or soils. By applying both primers on the same soils, we found that PHOD primers targeted a larger species spectrum than ALPS primers.

Dominant phyla harboring phoD in six soils.

Taxonomy was assigned to most sequences using BLAST+ (27) (Fig. 3; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). The remainder, 5,052 reads representing between 0.1 and 22% of the total filtered read number, were not assigned a taxonomic identity. In theory, the primers could amplify phoD in archaea and eukaryotes also, as phoD has been found in several archaeal and eukaryotic species in the IMG/M database. In the six soils studied here, both ALPS and PHOD primers amplified phoD from bacteria only, based on identification using BLAST+.

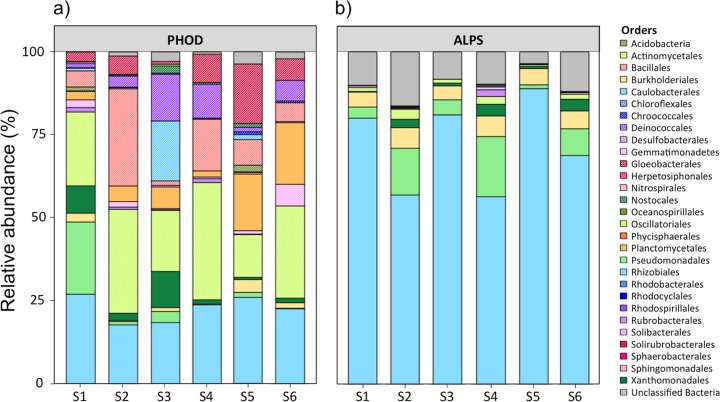

FIG 3.

Relative abundance as a percentage of the total community at the order level in samples S1 to S6 amplified by PHOD (a) and ALPS (b) primers.

PHOD primers targeted phoD genes from 13 phyla (Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Deinococcus-Thermus, Firmicutes, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospirae, Planctomycetes, Proteobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Verrucomicrobia). They covered 22 classes, 38 orders, 71 families, and 113 genera. The dominant orders were Actinomycetales (13 to 35%), Bacillales (1 to 29%), Gloeobacterales (1 to 18%), Rhizobiales (18 to 27%), and Pseudomonadales (0 to 22%). A libshuff analysis showed that the phoD bacterial communities in the different soils were significantly different from each other (P < 0.001). S1 was characterized by 25% Pseudomonadales and 10% Xanthomonadales. The highest relative abundance of Bacillales (29%) was found in S2. S3 had particularly high abundances of Caulobacterales (19%), Deinococcales (14%), and Xanthomonadales (11%). Planctomycetes were especially abundant in S4 and S6, with 18 and 19%, respectively, while S5 showed a high abundance of Gloeobacterales (18%).

ALPS primers amplified phoD genes from 6 phyla (Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, and Proteobacteria). In more detail, ALPS primers covered 13 classes, 22 orders, 42 families, and 64 genera. The most prevalent class was Alphaproteobacteria (55 to 92%). Rhizobiales was the dominant taxon in this class, with an overrepresentation of Methylobacterium sp., which represented 60 to 95% of the abundance of Rhizobiales. A libshuff analysis showed that the structures of the phoD bacterial communities in the different samples were also significantly different from each other (P < 0.001).

This taxonomy analysis highlights the fact that the phoD gene is widespread across phyla and that the PHOD primers covered the phoD diversity well. PHOD primers targeted phoD genes in 13 out of the 20 phyla known to carry the phoD gene, based on the IMG/M database. PHOD primers captured a particularly large diversity of Actinobacteria, including the common soil genera Actinomyces, Arthrobacter, Kineococcus, Kitasatospora, Micrococcus, and Streptosporangium (42), and of Proteobacteria, including Azorhizobium, Rhodospirillum, Caulobacter, Geobacter, and Variovorax (43). Both Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria are known to be important for mineralization of soil organic matter and in composting processes (44, 45). Our sequencing results for soils, in accordance with the IMG/M analysis, show that a greater diversity of microorganisms than previously thought contributes to organic P mineralization by secreting PhoD.

PHOD primers amplified many sequences belonging to phyla with low abundances in the IMG/M database. These sequences were affiliated with the phyla Deinococcus-Thermus (e.g., Deinobacter sp.), Nitrospirae (e.g., Nitrospira sp.), Spirochaetes (e.g., Spirochaeta sp.), Planctomycetes (e.g., Isosphaera sp. and Planctomyces sp.), and Verrucomicrobia (e.g., Opitutus sp.). The ALPS primers did not amplify phoD genes from these phyla. Moreover, compared to the PHOD primers, the ALPS primers failed to detect phoD genes from many genera, including, e.g., Anabaena, Chroococcidiopsis, and Chroococcus, belonging to the Cyanobacteria. Our results support the conclusion of Tan et al. (10) that the ALPS primers have an amplification bias, restraining the amplification to a limited number of microbial taxa and overrepresenting Alphaproteobacteria, probably because of the few sequences used to design the primers (7 sequences from 4 phyla used, compared with 315 sequences from 11 phyla used here for the primer design).

Soil pH is the main driver of the phoD bacterial community.

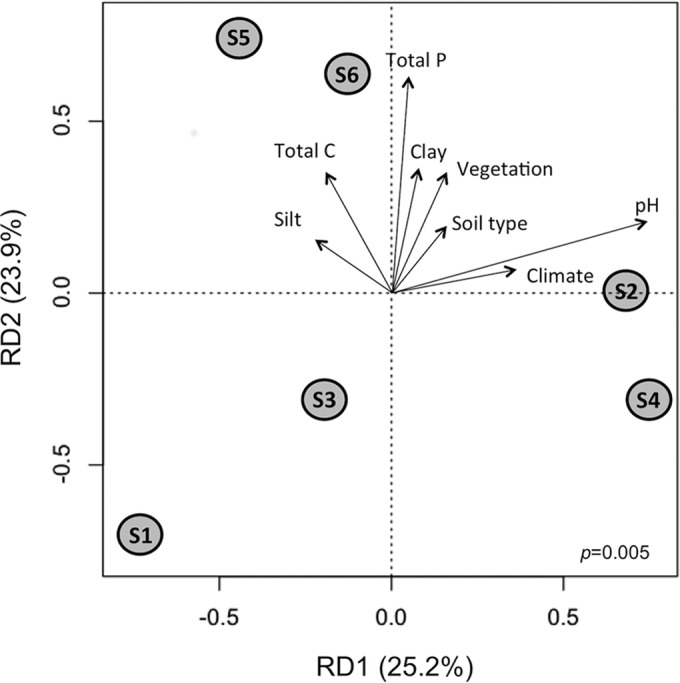

Redundancy analysis (RDA) of the PHOD-amplified samples indicated that 49.1% of the variation was explained by the two main RDA components (Fig. 4). Variance partitioning analysis showed that soil pH explained 23.7% and total P 18.3% of the variance among the communities. However, soil pH was the only environmental variable that was significantly correlated with the distribution of the samples (P = 0.03). The most divergent samples along the first RDA component axis were S1 and S4. The observed differences between these samples are likely due to the very contrasting soil and environmental properties between the sampling sites. S1 was taken from an oceanic and temperate climatic region with dense vegetation, while S4 was collected in a hot semiarid climatic region with only scattered vegetation, where lower soil microbial biomass and diversity are expected (46). S1 and S4 also exhibited the biggest difference in soil pH, which is regarded as the main environmental driving force that affects total microbial communities and activities (47, 48). Soil pH has previously been observed to be an important driver of the phoD bacterial community in the rhizosphere of wheat grown in different soils (15). Phosphatase activity can respond to changes in soil pH within days, e.g., after a lime treatment in agricultural soils (49). The second RDA component was linked mainly to total P. The phoD communities of S5 and S6 clustered together along the second-component axis, probably because these two samples were both collected in Switzerland and had high total carbon and other similar soil properties. In contrast, S1, S3, and S4 had low total C and P values.

FIG 4.

Redundancy analysis of the phoD bacterial community of samples S1 to S6 amplified by PHOD primers with the environmental variables clay and silt content, total C and P, soil type, climate, vegetation and soil pH. The significance of the model is indicated in the bottom right corner. Note that soil pH was the unique environmental variable that was significantly correlated with the phoD bacterial community (P = 0.03).

Previous studies using the ALPS primers have reported an effect of the application of organic and conventional fertilizers, crop management, vegetation, and pH (10, 12–16, 50). The plant community has been reported to have an impact on phoD diversity and community structure in monocultures (14, 15). P fertilization has been reported to either increase (10) or reduce (12) the diversity of the phoD gene. Jorquera et al. (13) observed that P fertilization alone did not affect the phoD bacterial community structure in a Chilean Andisol pasture, while combined N and P fertilization did change the phoD bacterial community structure. While all these studies have provided some insights into the environmental drivers affecting phoD bacterial communities, they need to be interpreted with caution due to the amplification bias of the ALPS primers toward Alphaproteobacteria described above. PHOD primers should now be applied to a wider range of soils to verify whether pH is the main driver of the phoD bacterial community.

In conclusion, evaluation of metagenomic data sets revealed that the phoD gene is found primarily in bacteria and is spread across 20 bacterial phyla. phoD has been found to be ubiquitous in the environment, with terrestrial ecosystem metagenomes containing the highest relative abundance of phoD. The newly designed PHOD primers reported here covered the large diversity of the phoD gene better than previously published primers and amplified sequences affiliated with 13 bacterial phyla. The most prevalent phoD genes identified in six diverse soils from Europe and Australia were affiliated with the orders Actinomycetales, Bacillales, Gloeobacterales, Rhizobiales, and Pseudomonadales. Soil pH was found to be the main environmental driver affecting the phoD bacterial community. PHOD primers can be used as a tool to study phoD bacterial community diversity and composition and to identify and quantify microorganisms that carry and express phoD in the environment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stefan Zoller for the Perl scripts for the taxonomic analysis and the Genetic Diversity Center (Zurich, Switzerland) for technical assistance. We also acknowledge Agroscope (Switzerland) and the New South Wales Department of Primary Industry (NSW, Australia) for access to the sampling sites.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) and by a research grant from the University of Sydney.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01823-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Westheimer FH. 1987. Why nature chose phosphates. Science 235:1173–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.2434996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vitousek PM, Porder S, Houlton BZ, Chadwick OA. 2010. Terrestrial phosphorus limitation: mechanisms, implications, and nitrogen-phosphorus interactions. Ecol Appl 20:5–15. doi: 10.1890/08-0127.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Condron LM, Turner BL, Cade-Menun BJ. 2005. Chemistry and dynamics of soil organic phosphorus, p 87–122. In Sims JT, Sharpley AN (ed), Phosphorus: agriculture and the environment. ASA, CSSA and SSSA, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vershinina OA, Znamenskaya LV. 2002. The Pho regulons of bacteria. Microbiology 71:497–511. doi: 10.1023/A:1020547616096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kageyama H, Tripathi K, Rai AK, Cha-um S, Waditee-Sirisattha R, Takabe T. 2011. An alkaline phosphatase/phosphodiesterase, PhoD, induced by salt stress and secreted out of the cells of Aphanothece halophytica, a halotolerant cyanobacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:5178–5183. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00667-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JR, Shien JH, Shieh HK, Hu CC, Gong SR, Chen LY, Chang PC. 2007. Cloning of the gene and characterization of the enzymatic properties of the monomeric alkaline phosphatase (PhoX) from Pasteurella multocida strain X-73. FEMS Microbiol Lett 267:113–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulanger RR, Kantrowitz ER. 2003. Characterization of a monomeric Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase formed upon a single amino acid substitution. J Biol Chem 278:23497–23501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo H, Benner R, Long RA, Hu J. 2009. Subcellular localization of marine bacterial alkaline phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:21219–21223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907586106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaheer R, Morton R, Proudfoot M, Yakunin A, Finan TM. 2009. Genetic and biochemical properties of an alkaline phosphatase PhoX family protein found in many bacteria. Environ Microbiol 11:1572–1587. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan H, Barret M, Mooij MJ, Rice O, Morrissey JP, Dobson A, Griffiths B, O'Gara F. 2013. Long-term phosphorus fertilisation increased the diversity of the total bacterial community and the phoD phosphorus mineraliser group in pasture soils. Biol Fertil Soils 49:661–672. doi: 10.1007/s00374-012-0755-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakurai M, Wasaki J, Tomizawa Y, Shinano T, Osaki M. 2008. Analysis of bacterial communities on alkaline phosphatase genes in soil supplied with organic matter. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 54:62–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2007.00210.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chhabra S, Brazil D, Morrissey J, Burke J, O'Gara F, Dowling DN. 2013. Fertilization management affects the alkaline phosphatase bacterial community in barley rhizosphere soil. Biol Fertil Soils 49:31−39. doi: 10.1007/s00374-012-0693-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorquera MA, Martínez OA, Marileo LG, Acuña JJ, Saggar S, Mora ML. 2014. Effect of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization on the composition of rhizobacterial communities of two Chilean Andisol pastures. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 30:99–107. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Marschner P, Zhang F. 2012. Phosphorus pools and other soil properties in the rhizosphere of wheat and legumes growing in three soils in monoculture or as a mixture of wheat and legume. Plant Soil 354:283–298. doi: 10.1007/s11104-011-1065-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Zhang F, Marschner P. 2012. Soil pH is the main factor influencing growth and rhizosphere properties of wheat following different pre-crops. Plant Soil 360:271–286. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1236-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser TD, Lynch DH, Bent E, Entz MH, Dunfield KE. 2015. Soil bacterial phoD gene abundance and expression in response to applied phosphorus and long-term management. Soil Biol Biochem 88:137−147. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markowitz VM, Chen I-MA, Chu K, Szeto E, Palaniappan K, Grechkin Y, Ratner A, Jacob B, Pati A, Huntemann M. 2012. IMG/M: the integrated metagenome data management and comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D123–D129. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y, Niu B, Gao Y, Fu L, Li W. 2010. CD-HIT suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics 26:680–682. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walters WA, Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Berg-Lyons D, Fierer N, Knight R. 2011. PrimerProspector: de novo design and taxonomic analysis of barcoded PCR primers. Bioinformatics 27:1159–1161. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulvik CA, Effler CT, Wilhelm SW, Buchen A. 2012. De-MetaST-BLAST: a tool for the validation of degenerate primer sets and data mining of publicly available metagenomes. PLoS One 7:e50362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. 2011. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez F, Lillington J, Johnson S, Timmel CR, Lea SM, Berks BC. 2014. Crystal structure of the Bacillus subtilis phosphodiesterase PhoD reveals an iron and calcium-containing active site. J Biol Chem 289:30889–30899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.604892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philippe H, Brinkmann H, Lavrov DV, Littlewood DTJ, Manuel M, Wörheide G, Baurain D. 2011. Resolving difficult phylogenetic questions: why more sequences are not enough. PLoS Biol 9:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chao AC, Shen T-J. 2003. Nonparametric estimation of Shannon's index of diversity when there are unseen species in sample. Environ Ecol Stat 10:429–443. doi: 10.1023/A:1026096204727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Good IJ. 1953. The population frequencies of species and the estimation of population parameters. Biometrika 40:237–264. doi: 10.1093/biomet/40.3-4.237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK. 2011. Estimating species richness, p 39–54. In Magurran AE, McGill BJ (ed), Biological diversity: frontiers in measurement and assessment, vol 12 Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schloss PD, Larget BR, Handelsman J. 2004. Integration of microbial ecology and statistics: a test to compare gene libraries. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:5485–5492. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5485-5492.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sait M, Hugenholtz P, Janssen PH. 2002. Cultivation of globally distributed soil bacteria from phylogenetic lineages previously only detected in cultivation-independent surveys. Environ Microbiol 4:654–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zappa S, Rolland J-L, Flament D, Gueguen Y, Boudrant J, Dietrich J. 2001. Characterization of a highly thermostable alkaline phosphatase from the euryarchaeon Pyrococcus abyssi. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:4504–4511. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4504-4511.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wende A, Johansson P, Vollrath R, Dyall-Smith M, Oesterhelt D, Grininger M. 2010. Structural and biochemical characterization of a halophilic archaeal alkaline phosphatase. J Mol Biol 400:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ŝnajdr J, Valŝková V, Merhautová V, Cajthaml T, Baldrian P. 2008. Activity and spatial distribution of lignocellulose-degrading enzymes during forest soil colonization by saprotrophic basidiomycetes. Enzyme Microb Technol 43:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2007.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyhrman ST, Ruttenberg KC. 2006. Presence and regulation of alkaline phosphatase activity in eukaryotic phytoplankton from the coastal ocean: implications for dissolved organic phosphorus remineralization. Limnol Oceanogr 51:1381–1390. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.3.1381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez NJ, Kidney BA. 2007. Alkaline phosphatase: beyond the liver. Vet Clin Pathol 36:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2007.tb00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sebastian M, Ammerman JW. 2009. The alkaline phosphatase PhoX is more widely distributed in marine bacteria than the classical PhoA. ISME J 3:563–572. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acinas SG, Sarma-Rupavtarm R, Klepac-Ceraj V, Polz MF. 2005. PCR-induced sequence artifacts and bias: insights from comparison of two 16S rRNA clone libraries constructed from the same sample. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:8966–8969. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8966-8969.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Limansky AS, Viale AM. 2002. Can composition and structural features of oligonucleotides contribute to their wide-scale applicability as random PCR primers in mapping bacterial genome diversity? J Microbiol Methods 50:291–297. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(02)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menzel P, Stadler PF, Gorodkin J. 2011. maxAlike: maximum likelihood-based sequence reconstruction with application to improved primer design for unknown sequences. Bioinformatics 27:317–325. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bora N, Ward A. 2008. The actinobacteria. In Goldman E, Green L (ed), Practical handbook of microbiology. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nacke H, Thürmer A, Wolher A, Will C, Hodac L, Herold N, Schöning I, Schrumpf M, Rolf D. 2011. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of bacterial community structure alon different management types in German forest and grassland soils. PLoS One 6:e17000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Danon M, Franke-Whittle IH, Insam H, Chen Y, Hadar Y. 2008. Molecular analysis of bacterial community succession during prolonged compost curing. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 65:133–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu H, Zeng G, Huang H, Xi X, Wang R, Huang D, Huang G, Li J. 2007. Microbial community succession and lignocellulose degradation during agricultural waste composting. Biodegradation 18:793–802. doi: 10.1007/s10532-007-9108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bachar A, Al-Ashhab A, Soares MIM, Sklarz MY, Angel R, Ungar ED, Gillor O. 2010. Soil microbial abundance and diversity along a low precipitation gradient. Microb Ecol 60:453–461. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9727-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N. 2009. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5111–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00335-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fierer N, Jackson RB. 2006. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:626–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507535103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dick WA, Cheng L, Wang P. 2000. Soil acid and alkaline phosphatase activity as pH adjustment indicators. Soil Biol Biochem 32:1915–1919. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00166-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fraser T, Lynch DH, Entz MH, Dunfield KE. 2014. Linking alkaline phosphatase activity with bacterial phoD gene abundance in soil from a long-term management trial. Geoderma 257–258:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kottek M, Grieser J, Beck C, Rudolf B, Rubel F. 2006. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol Z 15:259–263. doi: 10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/International Soil Reference and Information Centre/International Society of Soil Science. 1998. World reference base for soil resources. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson JM, Ingram JSI. 1993. Tropical soil biology and fertility: a handbook of methods, 2nd ed. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohno R, Zibilske LM. 1991. Determination of low concentrations of phosphorus in soil extracts using malachite green. Soil Sci Soc Am J 55:892–895. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1991.03615995005500030046x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.