Abstract

Cyanobacteria from Subsection V (Stigonematales) are important components of microbial mats in non-acidic terrestrial hot springs. Despite their diazotrophic nature (N2 fixers), their impact on the nitrogen cycle in such extreme ecosystems remains unknown. Here, we surveyed the identity and activity of diazotrophic cyanobacteria in the neutral hot spring of Porcelana (Northern Patagonia, Chile) during 2009 and 2011–2013. We used 16S rRNA and the nifH gene to analyze the distribution and diversity of diazotrophic cyanobacteria. Our results demonstrate the dominance of the heterocystous genus Mastigocladus (Stigonematales) along the entire temperature gradient of the hot spring (69–38 °C). In situ nitrogenase activity (acetylene reduction), nitrogen fixation rates (cellular uptake of 15N2) and nifH transcription levels in the microbial mats showed that nitrogen fixation and nifH mRNA expression were light-dependent. Nitrogen fixation activities were detected at temperatures ranging from 58 °C to 46 °C, with maximum daily rates of 600 nmol C2H4 cm−2 per day and 94.1 nmol N cm−2 per day. These activity patterns strongly suggest a heterocystous cyanobacterial origin and reveal a correlation between nitrogenase activity and nifH gene expression during diurnal cycles in thermal microbial mats. N and C fixation in the mats contributed ~3 g N m−2 per year and 27 g C m−2 per year, suggesting that these vital demands are fully met by the diazotrophic and photoautotrophic capacities of the cyanobacteria in the Porcelana hot spring.

Introduction

Hot springs represent extreme environments for life. They are typically dominated by a range of microorganisms that form well-defined ‘mats' that are constantly being over run by hot spring water. A variety of physical and chemical features, such as the pH (Hamilton et al., 2011; Loiacono et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2013), sulfide concentration (Purcell et al., 2007) and temperature (Miller et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013) shape the microbial presence and life cycle in these ecosystems. Temperature is considered the most important variable associated with changes and metabolic adaptations in microbial mat communities in hot springs with a neutral pH (Cole et al., 2013; Mackenzie et al., 2013).

Recently, the diversity of microbial thermophiles in many hot springs has been characterized (Nakagawa and Fukui, 2002; Meyer-Dombard et al., 2005; Hou et al., 2013; Inskeep et al., 2013). A range of thermophilic microorganisms (~75–40 °C) has been identified. Representatives of the bacterial phyla Cyanobacteria, Chloroflexi and Proteobacteria are the most commonly found microbes in neutral to alkaline hot springs (Otaki et al., 2012; Cole et al., 2013; Mackenzie et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013). Within the cyanobacteria, unicellular members such as Synechococcus and Cyanothece typically dominate at temperatures above 60 °C (Ward et al., 1998; Ward and Castenholz, 2000; Papke et al., 2003; Steunou et al., 2006, 2008). At lower temperatures (~60–40 °C), filamentous, non-heterocystous genera such as Phormidium and Oscillatoria and heterocystous genera such as Calothrix, Fischerella and Mastigocladus are common (Sompong et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2006; Finsinger et al., 2008; Coman et al., 2013). Although heterocystous cyanobacteria are richly represented in many hot springs with a neutral pH, their role and capacity as providers of fixed nitrogen is still unknown.

Nitrogen fixation is the process by which selected diazotrophs from Archaea and Bacteria consume atmospheric N2 gas as a substrate for growth (Stewart et al., 1967). This process may represent an important source of ‘new' nitrogen in the often nitrogen-limited hot spring waters. This process also counteracts the loss of combined nitrogen caused by denitrification in the poorly ventilated substrates of terrestrial hot springs (Otaki et al., 2012). N2 fixation has been assessed by screening for specific nif genes such as nifH (encoding the α-subunit of the nitrogenase enzyme complex), which is the most widely used molecular marker in the search for diazotrophs. Hence, the analysis of the presence of the nifH gene combined with measurements of nitrogenase activity (using the acetylene reduction assay) has been widely used to identify diazotrophs and diazotrophy in microbial mats from diverse environments (Stal et al., 1984; Bergman et al., 1997; Steunou et al., 2006; Díez et al., 2007; Severin and Stal, 2009; Desai et al., 2013).

Currently, the most thoroughly studied hot springs are those in Yellowstone National Park (YNP, Wyoming, USA), in which both nitrogenase activity and nifH gene transcription patterns have been examined (Miller et al., 2009; Hamilton et al., 2011; Loiacono et al., 2012). For example, nitrogenase activity was recorded in alkaline hot springs at temperatures of ~50 °C and was attributed to the heterocystous cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus (Stewart, 1970; Miller et al., 2006), whereas at higher temperatures in two other hot springs, the activity was credited to the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus (Steunou et al., 2006, 2008). However, heterotrophic bacteria and archaea are also highly represented as thermophiles in YNP acidic hot springs, including the presence of some active nitrogen fixers at temperatures up to 82 °C (Hamilton et al., 2011). Moreover, nifH genes have been detected at 89 °C in hot springs with varying pH values (1.9–9.8) (Hall et al., 2008; Loiacono et al., 2012).

Owing to the more ‘indirect' character of the ‘nitrogen fixation' activity provided by the acetylene reduction technique (which measures nitrogenase enzyme activity), verification of the results through measurements of the nitrogen fixation activity (that is, N2 gas uptake and cellular N incorporation using the 15N2 stable isotope assay) is highly recommended (Peterson and Burris, 1976; Montoya et al., 1996). However, 15N2 gas uptake has rarely been used to study nitrogen fixation by microorganisms in thermal hot springs. The only exception is the study of Stewart (1970) in an alkaline hot spring in YNP. Furthermore, measurements of nitrogenase activity by acetylene reduction assay (ARA), 15N2 uptake and nifH gene expression have not been evaluated together in a thermal microbial mat.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the role of diazotrophs in the nitrogen economy of the pristine, neutral terrestrial hot spring of Porcelana (Chile) with a focus on cyanobacteria. To achieve this goal, we examined the molecular identity (16S rRNA and nifH genes) of diazotrophic cyanobacteria and estimated their daily in situ nitrogenase activity and 15N2 uptake in combination with nifH gene expression in a series of interannual analyses (2009, 2011–2013). Our data show that cyanobacteria are capable of fulfilling the nitrogen demands of hot spring microbial mats through their nitrogen fixation activity.

Materials and methods

Study site and sampling strategies

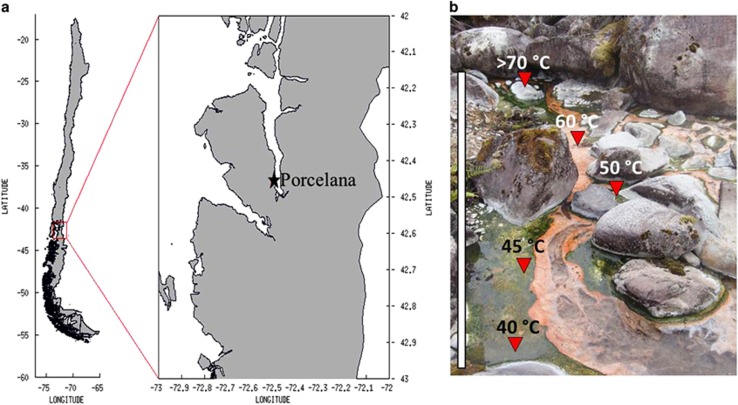

The study was conducted in the hot spring of Porcelana located ~100 m above sea level at 42°27′29.1″S–72°27′39.3″W in northern Patagonia, Chile (Figure 1a). A similar thermophilic temperature range (>69–38 °C) was registered during the sampling and experimentation during late summer (March) of the 4 years, 2009 and 2011–2013. Temperature, pH and dissolved O2 percentages were monitored using a multiparameter instrument (Oakton, Des Plaines, IL, USA; model 35607-85). Microbial mat samples (1 cm thick) used for in situ ARA and 15N2 uptake experiments and DNA/RNA analysis were obtained using a cork borer with a diameter of 7 mm. An extra three cores not used in the in situ analysis were included to generate enough material for the DNA/RNA analyses. Spring water (5 ml) and microbial mat samples were collected in triplicate for nutrient (NH4+, NO3−, NO2− and PO43−) and total chlorophyll determinations. Dissolved Fe concentrations were determined in the same samples using ICP-Mass spectrometry X series 2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) after preconcentration with ammonium 1-pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate/diethylammonium diethyldithiocarbamate organic extraction (Bruland and Coale, 1985). All samples were stored in liquid nitrogen during transportation to the laboratory and at −80 °C until processing.

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the Porcelana hot spring in northern Patagonia, Chile (X Region, Comau fjord). (b) The pigmented microbial mat was formed throughout the temperature gradient; the sampling sites are indicated by red triangles. The gray bar represents the mat extension (~10 m) within the thermophilic temperature gradient.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis

DNA was extracted as described previously (Bauer et al., 2008). Before DNA extraction, the samples were placed in a Lysing Matrix E tube (Qbiogene, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing lysis buffer and solid-glass beads (1 mm) to homogenize the microbial cells by bead beating (4.0 ms−1 for 20 s). The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA were determined using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) and by inspection after separation in a 1% agarose gel. Then, the total DNA was used as the template for PCR amplifications of cyanobacterial 16S rRNA genes using the cyanobacteria-specific primers CYA106F with a GC clamp (5′ 40 nucleotide GC tail) and CYA781R(a)–CYA781R(b) (Nübel et al., 1997) to generate amplicons 600 nucleotides in length. The DNA was also used as a template for amplification of the nifH genes using the diazotrophic cyanobacteria-specific primers CN Forward (CNF) with a GC clamp and CN Reverse (CNR) (Olson et al., 1998) to generate amplicons 350 nucleotides in length. The amplicons were resolved using a denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) approach with a D-code system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the protocol of Díez et al. (2007). The gradients of DNA denaturant agents used in the gels were 45–75% for the 16S rRNA gene and 45–65% for the nifH gene. DGGE bands located in the same position in the gel were assigned to the same microbial population. Several of the bands with the same position were excised from the gel, reamplified and sequenced, as were all bands located at different positions along the gel. The excised DGGE bands were eluted in 20 μl DNAse/RNAse-free dH2O (ultraPURE; Apiroflex, Santiago, Chile) and stored at 4 °C overnight. An aliquot of the eluted DNA was subjected to an additional PCR amplification using the corresponding primers (without GC clamp) before sequencing (Macrogen Inc., Seoul, Korea). Each specific DGGE band retrieved was assigned to one sequence representing a specific phylotype. The sequences were edited using the BioEdit software (Sequence Alignment Editor Software V.7.0.5.3., Carlsbad, CA, USA), followed by a basic local alignment and the use of a search tool (BLASTN) (Altschul et al., 1997).

Bacterial nifH gene clone library

The diversity of diazotrophic prokaryotes present in the microbial mat throughout the thermal gradient was determined using nifH gene clone libraries. PCR amplifications of the nifH gene were performed using the universal primers PolF/PolR (Poly et al., 2001) that cover most of the known diazotrophic organisms (Bacteria and Archaea), including cyanobacteria (Mårtensson et al., 2009; Díez et al., 2012). These primers amplify fragments 360 bp in length. The PCR products were purified (Wizard Clean-Up System; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and cloned using the commercial pJET1.2/blunt Cloning Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Clones with the proper insert sequence were validated using the primer vector set pJetF/pJetR (amplicon length ~550–600 bp). Fifty to one hundred clones obtained from each library (12 clone libraries in total) were selected for cyanobacterial-specific nifH gene amplifications using the primers CNF and CNR (Olson et al., 1998). These primers amplify a fragment within the insert generated by the universal primers PolF/PolR (Poly et al., 2001). Several of the amplified PCR products were sequenced to check for cyanobacterial genetic identities. Clones that did not amplify with the cyanobacterial primers CNF and CNR were assumed to correspond to other types of bacteria and were also sequenced. All sequences obtained were edited using the BioEdit software (Sequence Alignment Editor Software V.7.0.5.3.). The operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with 98% similarity were assigned using BLASTCLUST-BLAST score-based single-linkage clustering (Schloss and Westcott, 2011). The closest relatives to all OTUs were assigned using the BLASTN tool (National Center for Biotechnology Information database).

Phylogenetic reconstruction and statistical analysis

The 16S rRNA phylotypes retrieved from the DGGE band sequences, the reference taxa and the closest relatives from GenBank (only from published studies or cultures) were aligned using BioEdit with the ClustalW tool (Tom Hall; Ibis Therapeutics, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The same procedure was used for the nifH-DGGE band sequences and the nifH OTUs from the constructed clone libraries. The subsequent phylogenetic reconstruction using the maximum-likelihood search strategy with 10 000 bootstrap replicates was performed for each gene data set. The sequences of Gloeobacter violaceus and Desulfovibrio salexigens were used as outgroups for the 16S rRNA and nifH gene phylogenetic reconstructions, respectively.

The obtained 16S rRNA and nifH sequences (16S rRNA-DGGE band and nifH OTUs) were subjected to cluster analysis and BEST tests using PRIMER 6. The dendrograms generated for both genes were constructed to elucidate the similarity between the samples collected during different years and along the temperature gradient. The BEST test was performed to estimate the environmental factors that best explained the microbial species distributions. Additionally, correspondence analysis and redundancy analysis analyses (Clarke, 1993) were performed based on the relative abundances of 16S rRNA-DGGE bands and nifH OTUs and the environmental variables recorded each year to pinpoint the environmental variable (s) that most strongly influenced the microbial mat community.

RNA extraction and real-time qPCR measurements

Biological replicates from the acetylene reduction assay (three cores each) plus some additional non-assayed samples were used for the subsequent RNA analysis. These samples were collected throughout the day–night cycle (at 1200, 1300, 1400, 1600, 1800, 2000, 2300 and 0300 hours) and at three different temperatures (58 °C, 48 °C and 47 °C) in 2 years (2012 and 2013). RNA from the samples was extracted using Trizol and the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit according to manufacturer's specifications (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The quality and quantity of the RNA were determined using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) and by electrophoresis in an RNase-free 1% agarose gel. DNase treatment (TURBO DNA-free kit; Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was performed, and 1 μg of RNA from each sample (in duplicate) was used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) standardization. Then, the cDNA was synthesized using a selective cDNA Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's specifications with the universal nifH gene primers PolF/PolR (Poly et al., 2001). For qPCR, the nifH gene was cloned into the TOPO vector plasmid to obtain the plasmid stock concentration (1010 copies) and the plasmid curve (102–108 copies). The SensiMix kit (Bioline, Taunton, MA, USA) was used for the fluorescence signal, and the real-time qPCR (Roche LC 480 Roche diagnostics Ltd., Mannheim, Germany) program was run as follows: 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 59 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 30 s. To avoid nonspecific fluorescence, only fluorescence within the CP (crossing point) range given by the plasmid standard curve was considered and melting curves were only considered if they showed a unique product.

Measurement of nitrogenase activity ARA

The ARA was used to assess nitrogenase activity in the microbial mats throughout the temperature gradient of the hot spring. This assay was performed according to the procedure described by Capone (1993). At each temperature, four biological replicates composed of three microbial mat cores each (7 mm in diameter and 1 cm thick) were placed in presterilized 10 ml glass incubation vials containing 1 ml of prefiltered (0.2 μm filter pore) spring water and sealed using Mininert valves STD (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). The samples were incubated for 2 h following replacement of 1 ml of air with 1 ml of acetylene gas (10–20% of the gas phase) generated from calcium carbide (CaC2+H2O=Ca(OH)2+C2H2). The four replicates plus two controls (one with microbial mat cores but no acetylene gas and one containing only acetylene gas but no cores) were incubated at their original in situ temperature in the field. The first control was used to estimate any natural ‘background' ethylene generated by the microbial community, and the second control was used to estimate any ethylene generated in the calcium carbide reaction. After incubations during diel cycles (1300, 1400, 1700, 2300 and 0300 hours), 5 ml of the gas phase was withdrawn from each vial using a hypodermic syringe and transferred to a 5 ml BD vacutainer (no additive Z plus tube, REF367624). After transporting the vacutainers to the laboratory, the ethylene produced was analyzed by injecting 1 ml of the gas using a gas-tight syringe (Hamilton) into a GC-8A gas chromatograph (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an 80/100 Porapak Q (Supelco, St Louis, MO, USA) 1 m × 1/4 in column and a flame ionization detector using helium as the carrier gas. A commercial ethylene standard of 100 p.p.m. (Scotty Analyzed Gases, Sigma-Aldrich) in air was used to estimate the ethylene produced. Acetylene (20% in air) was used as an internal standard (Stal, 1988). The nitrogenase activity calculated from the ethylene produced was corrected using the two controls and expressed per surface area of microbial mat cores and time.

Isotopic nitrogen assimilation (15N2) and carbon (H13CO3−) uptake

In parallel to the ARA measurements performed in 2012 and 2013, samples from the microbial mats were collected for 15N and 13C uptake experiments. The experiments (15N2 and H13CO3−) were performed using three biological replicates composed of three microbial mat cores each (7 mm in diameter and 1 cm thick). The cores were placed in presterilized 12 ml vials with 1 ml of prefiltered (0.2 μm filter pore) spring water and incubated at the corresponding in situ temperatures. The 15N uptake experiments were initiated through the addition of 1 ml of 15N2 gas (98% atom 15N2 gas; Sigma-Aldrich) through a gas-tight syringe into the headspace of each vial. To estimate the carbon (H13CO3−) uptake, 500 μl of H13CO3− (500 μm) was added to the vials. Additionally, two replicate vials without the isotope (15N2 and 13C) were incubated to determine the natural isotopic composition (control). The vials were incubated in situ for 2 or 6 h and then the cores were dried at 70 °C for 48 h. Measurement of 15N and 13C atom incorporation (AT 15N and 13C) were performed using a mass spectrometer (IRMS delta plus, Thermo FinniganH; Stable Isotope Laboratory, Granada, Spain), and the C:N ratio (organic matter composition of the sample) was determined. Calculations of the 15N and 13C assimilation rates were performed as described by Montoya et al. (1996) and Fernandez et al. (2009), including corrections by dilutions of 15N2 gas and controls.

Results

Geochemistry of the Porcelana hot spring

The Porcelana hot spring (Figure 1) shows a continuous outflow of hot water, thereby forming a decreasing temperature gradient away from the well. The water temperature ranged from 69 °C to 38 °C over the gradient investigated, with some variation in maximum temperatures between years (Table 1). A brightly pigmented microbial mat (~3 cm deep) extended 7–10 m away from the well (Figure 1b) at the bottom of the water stream. The decreasing temperature gradient resulted in increasing water oxygen solubility. The physicochemical features of the mat were comparatively constant over time (Table 1). The pH was close to neutral (~6.5), and the macronutrient concentrations were on average 1.9 μmol l−1 NO3−, 0.6 μmol l−1 NO2−, 0.03 μmol l−1 NH4+ and 51.4 μmol l−1 PO43− over the 2011–2013 period (Table 1). The nitrate concentration was examined during the day and night periods and at two temperatures (52 °C and 47 °C) in 2012. No variations were apparent between day and night, although the nitrate levels were almost threefold higher at 52 °C (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S1). The dissolved Fe concentrations were ~0.07 μmol l−1 in 2012 and 2013 (Table 1).

Table 1. Physical and chemical variables registered in the Porcelana hot spring at different locations along the microbial mat during the years 2009 and 2011–2013.

| Year | T (°C) | O2 % Sat. | pH | NO3− (μmol l−1) | NO2− (μmol l−1) | NH4+ (μmol l−1) | PO4− (μmol l−1) | Fe (μmol l−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 46 | 42 | 5.2 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2009 | 42 | 46 | 6.4 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2009 | 40 | 43 | 6.1 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2009 | 38 | 48 | 5.1 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2011 | 69 | 54 | 6.9 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2011 | 64 | 59 | 6.7 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2011 | 61 | 80 | 6.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2011 | 57 | 82 | 6.8 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2011 | 51 | 90 | 6.7 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2012 | 52 | 104 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 29.7 | ND* |

| 2012 | 47 | 108 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 43.5 | 0.02 |

| 2013 | 66 | 72 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 115 | 0.05 |

| 2013 | 65 | 73 | 6.8 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 47.4 | 0.07 |

| 2013 | 58 | 86 | 6.8 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 38.4 | 0.14 |

| 2013 | 48 | 94 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 34.1 | 0.06 |

Abbreviation: ND*, data not determined.

Interannual cyanobacterial diversity

The cyanobacterial diversity in the microbial mat growing along the temperature gradient was examined during the years 2009 and 2011–2013. The analyses were performed by DGGE using the cyanobacterial-specific 16S rRNA gene as the diversity marker (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S3a). The resulting DGGE bands (five in total) revealed the existence of differently distributed sub-populations along the temperature gradient. The bands corresponded with members of the phylum Cyanobacteria and specifically with members within the heterocystous order Stigonematales (DGGE band CYA5; GenBank accession numbers for nucleotide sequences: KJ696694) and the non-heterocystous order Oscillatoriales (DGGE band CYA1-4; GenBank accession numbers for nucleotide sequences: KJ696687–KJ696690) (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1).

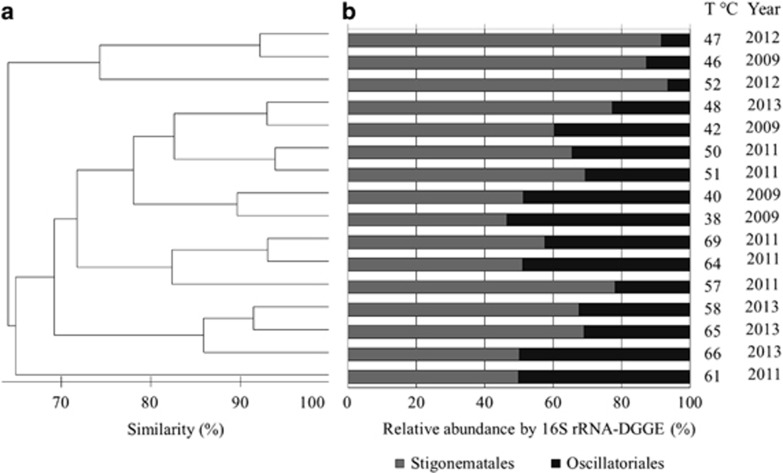

Cluster analysis of the 16S rRNA gene marker was performed using PRIMER 6 (Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index dendrogram) assuming the presence or absence of the DGGE bands together with their relative abundance throughout the temperature gradient in the 4 years (Figure 2). Up to 70% similarity was apparent for all samples denoted as cyanobacteria in the dendrogram (Figure 2a). However, samples collected from similar temperatures within the same year grouped as pairs showed >90% similarity. This result may be explained by the similar relative abundances of the cyanobacteria (analyzed by 16S rRNA genes) exhibited by the pairs (Figure 2b). Additionally, most pairs showed >80% similarity with a third sample collected during the same year or at a similar temperature. This result illustrates the strong influence of temperatures and interannual variations on the cyanobacterial community.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the interannual cyanobacterial diversity at different temperatures in the Porcelana hot spring based on the 16S rRNA gene and DGGE. (a) Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index dendrogram. (b) Relative abundance of 16S rRNA-DGGE bands (phylotypes) for each temperature and year investigated.

Phylogenetic reconstructions of the sequences retrieved from the DGGE bands using the 16S rRNA gene confirmed the placement of the hot spring cyanobacteria within the filamentous non-heterocystous order Oscillatoriales (Section III) and the heterocystous order Stigonematales (Section V) (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S2). The four 16S rRNA-DGGE bands CYA1–CYA4 (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S3a) formed clusters with members of the genera Leptolyngbya and Oscillatoria (Oscillatoriales) with a 99% similarity according to the BLASTN analyses (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, the even more prevalent 16S rRNA-DGGE band CYA5 (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S3a) was closely related to members of the Mastigocladus and Fischerella genera (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1). The tentatively identified Mastigocladus phylotype (CYA5) was the only phylotype present along the entire temperature gradient (i.e., from 69 °C to 38 °C); CYA5 also exhibited the highest relative abundance in 16S rRNA gene sequences at higher temperatures (57–46 °C) (Figure 2b). Within this temperature range, the Mastigocladus phylotype represented an average of 66% of the total cyanobacterial community; the remaining 34% was represented by Oscillatoriales phylotypes.

BEST analysis relating the 16S rRNA phylotypes identified by DGGE to the recorded in situ environmental variables including temperature (°C), dissolved oxygen (%), pH and nitrogen compounds (NO3−, NO2− and NH4+) (Table 1) showed that variations in temperature and pH explained 77% of the similarity between the phylotypes (ρ-value 0.109; significance level 91%). These results were corroborated using canonical correspondence analysis, which showed that temperature, pH and NO2− represented the major ecological drivers of the phylotype distribution in the Porcelana hot spring (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S5).

Interannual diversity of cyanobacterial diazotrophs

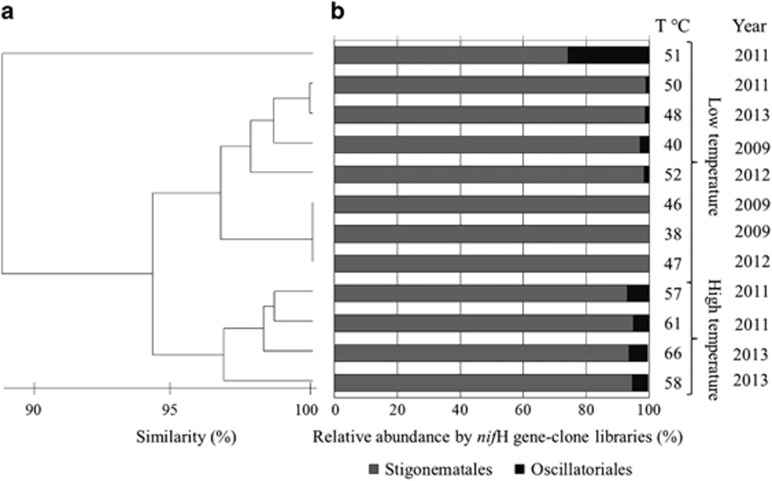

The diversity of diazotrophs in the hot spring was investigated by constructing clone libraries targeting the nifH gene using universal primers (Poly et al., 2001). Fifty to one hundred clones were obtained from the 12 libraries constructed (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1). To identify clones related to cyanobacteria, the clones were reamplified using the cyanobacterial-specific nifH gene primers (Olson et al., 1998). Fifteen to fifty clones in each library were found to represent cyanobacterial phylotypes. All of the retrieved sequences (GenBank accession numbers for nucleotide sequences: KM507492–KM507497) were analyzed using BLASTCLUST-BLAST (Schloss and Westcott, 2011) to identify the OTUs present in each clone library (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1). A total of six cyanobacterial nifH OTUs were apparent, three of which were determined to be closely affiliated (>98% nucleotide sequence identity) to the heterocystous genus Mastigocladus (Stigonematales) by BLASTN analysis (Figure 3b, Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1). The other three OTUs were affiliated with the Oscillatoriales (>88% nucleotide sequence identity) and more specifically with the genera Leptolyngbya and Oscillatoria (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1). A phylogenetic reconstruction of the six nifH gene OTUs and the closest related sequences from the database confirmed the identities obtained by BLASTN (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S4). As shown in Figure 3a, similarity cluster analysis of the nifH OTUs demonstrated that all of the microbial mat samples collected in the spring were highly stable and exhibited >95% similarity in the community that was independent of the temperature and the year investigated. The dominance of the Mastigocladus OTUs identified by nifH gene analysis was confirmed (93% on average) at all temperatures, whereas the Oscillatoriales OTUs were comparatively rare (7% average) (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Relative abundance and interannual diazotrophic bacterial diversity in the Porcelana hot spring based on the nifH marker gene and clone libraries. (a) Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index dendrogram. (b) Relative abundance of the nifH gene (OTUs) determined using clone libraries obtained for each temperature and year investigated.

Redundancy analysis of the nifH gene OTUs and the in situ recorded environmental variables including temperature (°C), dissolved oxygen (%), pH and nitrogen compounds (NO3−, NO2− and NH4+) (Table 1) showed that the temperature and nutrients (NH4+ and NO2−) explained the distribution and high relative abundance of the Mastigocladus nifH gene OTUs in the spring (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S6).

The identity of the cyanobacterial OTUs obtained using the nifH clone libraries were verified via the DGGE approach using the same cyanobacterial-specific nifH primers (Olson et al., 1998). Three nifH-DGGE bands (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S3b) were retrieved and affiliated with M. laminosus with 99% sequence similarity (BLASTN tool; GenBank accession numbers for nucleotide sequences: KJ696698–KJ696700) (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table S1). None of the nifH-DGGE bands were affiliated with members of the Oscillatoriales.

A phylogenetic reconstruction combining the sequenced nifH gene OTUs and nifH-DGGE bands with their closest matches in the database (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figure S4) showed that all of the genes clustered to Stigonematales with sequences related to the thermophilic M. laminosus. The Oscillatoriales OTUs clustered with the ‘Filamentous thermophilic cyanobacterium sp.' (accession number: KM507495 and KM507496) and Leptolyngbya sp. (accession number: KM507497).

Biological nitrogen fixation

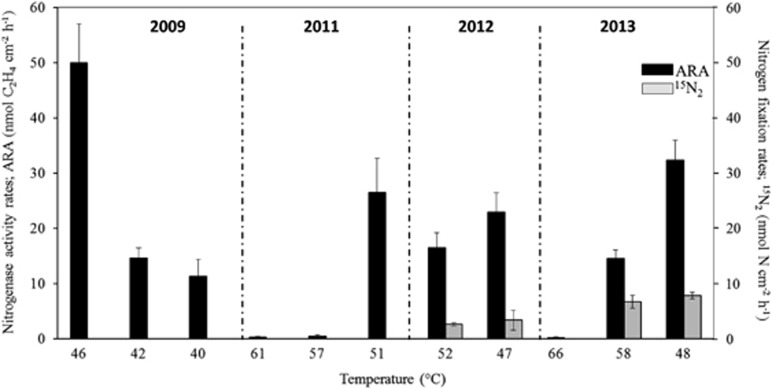

Owing to the high presence of potential diazotrophic cyanobacteria in the microbial mat of the Porcelana hot spring, the nitrogen fixation process was recorded using two approaches: the sensitive acetylene reduction assay (ARA-GC) to estimate the nitrogenase enzyme activity (years 2009 and 2011–2013) and the 15N2 stable isotope uptake to estimate the biological incorporation of nitrogen into the biomass (years 2012 and 2013) using mass spectroscopy. As shown in Figure 4 and Table 2, the total nitrogenase activity recorded along the temperature gradient at mid-day (1200–1400 hours) varied from 0.2 (±s.d. 0.01) to 50.0 (±s.d. 7.0) nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1. The highest rates were recorded at 46–48 °C, whereas higher temperatures (Figure 4) and darkness (Figure 5) gave a lower activity.

Figure 4.

Nitrogen fixation assessed by the ARA and 15N2 uptake analysis for the different temperatures and years investigated. ARA measurements (black bars) were conducted during the 4 years, whereas 15N2 uptake measurements (gray bars) were performed in 2012 and 2013.

Table 2. The contribution of nitrogenase activity, nitrogen fixation and carbon assimilation rates, the C2H4:N2 ratio and the percentage of nitrogen fixation to the total PPa and Pnewb in the Porcelana hot spring.

| Year | T (°C) |

Hourly rates |

Daily rates |

Ratios |

% Nitrogen fixation contribution to |

Input of daily nitrogen fixation to microbial mat | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogenase activity (nmol cm−2 h−1) | Nitrogen fixation (nmol N cm−2 h−1) | Nitrogen fixationc (nmol N cm−2 h−1) | Carbon assimilation (nmol C cm−2 h−1) | Nitrogenase activity (nmol cm−2 per day) | Nitrogen fixation (nmol N m−2 per day) | Carbon assimilation (nmol C cm−2 per day) | C2H4:N2 | C:Nd | Total daily primary production PP (C) | Total new production Pnew (N) | g N m−2 per year | ||

| 2009 | 46 | 50.0±7.0 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 600±84.1 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2009 | 42 | 14.6±1.8 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 175±21.8 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2009 | 40 | 11.3±3.1 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 136±36.6 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2011 | 61 | 0.3±0.1 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 3.6±1.6 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2011 | 57 | 0.5±0.3 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 6.1±3.0 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2011 | 51 | 26.5±6.2 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 318±74.4 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2012 | 52 | 16.5±2.7 | 2.6±0.3 | 1.4±0.1 | 53.0±4.1 | 198±32.4 | 31.4±3.24 | 636±49 | 6.3 | 18.7 | 92.2 | 99.1 | 1.6 |

| 2012 | 47 | 22.9±3.5 | 3.4±1.8 | 4.6±1.8 | ND* | 275±42.5 | 40.2±21.6 | ND* | 6.8 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 2.9 |

| 2013 | 66 | 0.2±0.01 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 2.8±0.1 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| 2013 | 58 | 14.5±1.6 | 6.7±1.2 | 1.6±0.3 | 45.8±8.7 | 174±19.7 | 80.0±14.3 | 550±105 | 2.2 | 9.1 | 132 | 99.8 | 4.1 |

| 2013 | 48 | 32.4±3.6 | 7.8±0.6 | 6.3±1.8 | ND* | 388±42.9 | 94.1±6.9 | ND* | 4.1 | ND* | ND* | ND* | 4.8 |

Abbreviations: ND*, data not determined; Pnew, new nitrogen production; PP, primary production.

The values were calculated from those obtained during daytime (1200–1400 hours).

Nmol C cm−2 per day.

Nmol N cm−2 per day.

Nitrogen fixation rates for 6 h in situ incubation.

C:N based on organic matter calculated by mass spectrometer instrument.

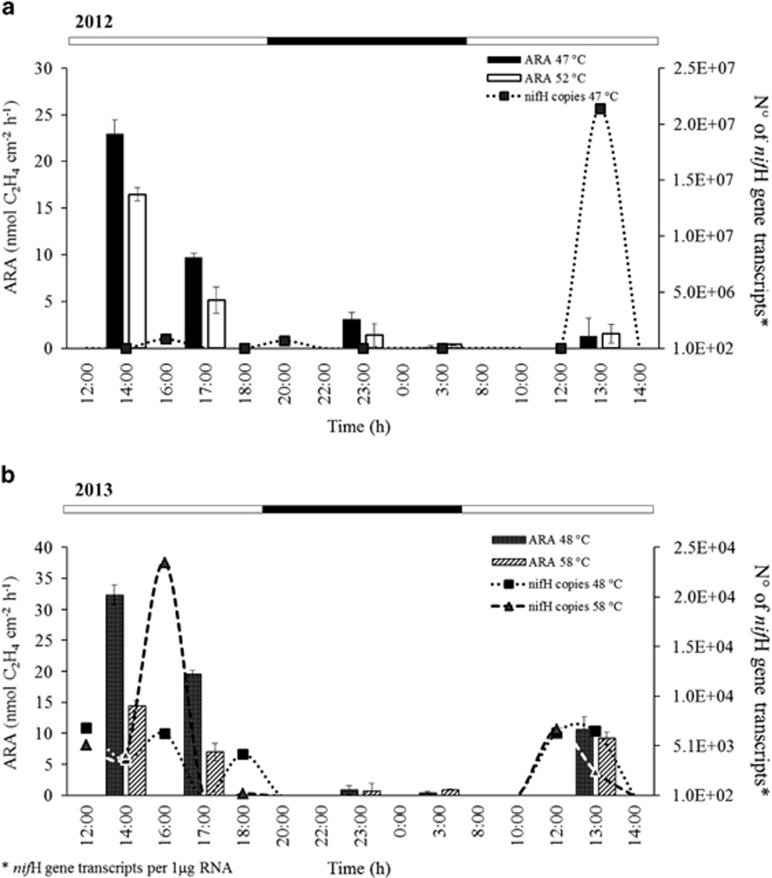

Figure 5.

Diel cycles in nitrogenase activity (NA) and nifH gene expression in the Porcelana hot spring. (a) Diel cycles at different temperatures in 2012. The bars represent ARA and the dotted line represents the number of nifH gene transcripts at 47 °C. (b) Diel cycles at different temperatures in 2013. The bars and the dashed line represent activities at 58 °C and 48 °C. Error bars indicate the s.d. The top bar represents the light (white) and night (black) periods; the latter is also illustrated by gray shading.

Analysis of the cellular incorporation of nitrogen (Table 2) after 2-h (1200–1400 hours) and 6-h (1200–1800 hours) incubations showed incorporation of 15N (Table 2 and Figure 4). The highest nitrogen incorporation recorded was 7.8 nmol N cm−2 h−1 (±s.d. 0.6) at 48 °C in 2013, coinciding with the highest nitrogenase activity at the same temperature and year (Table 2). No difference in activity was observed following incubations for 2 or 6 h (Table 2). The theoretical ratio between the acetylene reduction (ARA) and the isotopic N2 fixation method (C2H4:N2) is 4:1. The ratio for the Porcelana hot spring microbial mat was close to this theoretical ratio, ranging from 2.2:1 to 6.8:1 (Table 2).

Based on the 15N uptake quantities, the ‘new' yearly nitrogen inputs into the Porcelana hot spring were extrapolated to represent up to 2.9 g N m−2 per year in 2012 and 4.8 g N m−2 per year in 2013 (Table 2).

Diel cycles of nitrogenase activity and nifH gene expression

Based on the fact that the optimum temperature for nitrogenase activity in the Porcelana hot spring was between 58 °C and 46 °C (Figure 4), this temperature interval were selected to determine the nitrogenase activity and nifH gene expression in greater detail throughout the day during two consecutive days in 2012 and 2013. As shown in Figure 5, the nitrogenase activity peaked at mid-day (at ~1300–1400 hours) irrespective of the temperature and approached zero at night. Similar diel nitrogenase activity patterns were observed in both years, peaking at 22.9 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1 at 47 °C in 2012 and 32.4 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1 at 48 °C in 2013 (Table 2). The nitrogenase activity was consistently higher at lower temperatures (47–48 °C). Next, the biological sample replicates used for the nitrogenase assays (three cores in each vial) were combined with extra microbial mat material to examine the diel cycles of nifH gene expression (Figure 5). In 2012, the nifH gene expression was measured only at 47 °C. Maximum transcript levels occurred around mid-day (day 2) with 2.1 × 107 nifH gene transcripts identified. In 2012, two lower expression peaks were noted at 1600 hours (5.2 × 105) and 2000 hours (6.6 × 105); this pattern was also observed in 2013. The highest transcription level (2.4 × 104) was found at ~1600 hours and 58 °C, whereas no nifH expression took place in the dark–night time when examined in 2012 and 2013.

Carbon fixation

Because the data showed that the Porcelana microbial mat was dominated by cyanobacteria, the in situ incorporation of 13C-labeled bicarbonate (H13CO3−) was followed in 2012 and 2013. The incubations with H13CO3− lasted 2 h (1200–1400 hours) under the same conditions described for the nitrogen fixation assays (i.e., at 52 °C and 58 °C) (Table 2). The highest carbon incorporation recorded was 53.0 (±s.d. 4.1) and 45.8 (±s.d. 8.7) nmol C cm−2 h−1 at 52 °C and 58 °C, respectively, during the two consecutive years (Table 2). Extrapolation to a yearly incorporation showed an average C uptake of ~27 g C fixed m−2 per year in the Porcelana hot spring.

Contribution of combined nitrogen to the Porcelana microbial community

Taking into account the daily rates of 15N2 uptake, H13CO3− assimilation and the C:N ratio (Table 2), it was apparent that the photoautotrophic nitrogen fixers present in the Porcelana microbial mat sustained these key nutrient demands to a large extent. Even when the daily rates found for nitrate assimilation (15NO3−) (data not shown) were considered, the total ‘new' production of nitrogen fixation (15N) contributed up to 99% of the ‘new' N input into the microbial mat of the Porcelana hot spring (Table 2). The analyses were performed according to the protocol of Raimbault and Garcia (2008), although the data were not corrected for nitrification.

Discussion

Although thermal systems around the world have attracted considerable interest and their overall biology and organisms have been characterized (Stewart, 1970; Miller et al., 2006; Steunou et al., 2008; Hamilton et al., 2011; Loiacono et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2013), our knowledge on the identity and relevance of diazotrophs in such systems has remained surprisingly rudimentary. The distinct microbial mats or biofilms formed in hot springs typically harbor phototrophic microorganisms that often belong to the phyla Cyanobacteria and Chloroflexi (Liu et al., 2011; Klatt et al., 2013). Because certain members of these phyla (together with archaea) may fix atmospheric dinitrogen gas (N2), this organismal segment may serve an important key nutrient (N) role in these ecosystems, as was recently suggested (Steunou et al., 2006, 2008; Hamilton et al., 2011; Loiacono et al., 2012).

To extend our knowledge concerning the significance of thermal diazotrophs, we performed the first detailed examination by combining analyses of the genetic diversity of microbes, their diazotrophic capacity and estimates of their contribution to ‘new' nitrogen in the neutral hot spring Porcelana (Patagonia, Chile). The high volcanic activity in Chile has generated a large number of largely unexplored terrestrial hot springs with distinct physicochemical parameters; some of the hot springs exhibit characteristics resembling those of other well-studied hot spring areas (for example, YNP) (Hauser, 1989; Hamilton et al., 2011; Loiacono et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013). The pristine hot spring of Porcelana was selected because this spring represents a stable ecosystem appropriate for identifying microbes and factors that control their behavior in the community. The lush microbial mats of the Porcelana thermal gradient (~69–38 °C) are likely supported by the nitrogen, phosphate and iron levels typical for the Porcelana water system and contain microbes belonging to Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria and Chloroflexi (Mackenzie et al., 2013). Hence, we hypothesized the existence of a rich diazotrophic community in the Porcelana spring, making it an ideal model system for exploration.

The polyphasic approach used in our study of the Porcelana hot spring in combination with several methodological approaches such as molecular markers (16S rRNA and nifH genes), molecular techniques (clone libraries, DGGE and RT-qPCR), in situ enzyme activities (ARA) and isotope uptake (15N2 and H13CO3−) established that the Porcelana hot spring is dominated by cyanobacteria, particularly the diazotrophic genus Mastigocladus (Stigonematales). Cyanobacteria have been identified in other thermal microbial mats included members of the unicellular Synechococcales (mainly the genus Synechococcus) (Sompong et al., 2005; Steunou et al., 2006, 2008) and the filamentous Stigonematales (genera Fischerella and Mastigocladus) (Miller et al., 2006; Lacap et al., 2007, 2007; Finsinger et al., 2008). The dominating cyanobacterial phylotypes discovered in the microbial mats of the Porcelana hot spring corroborated these data, with the exception of the unicellular cyanobacteria. The presence of the Stigonematales phylotypes was also verified by morphological analysis (microscopy; data not shown).

Using the nifH genes as a marker allowed a more accurate determination of the affiliation of the dominating cyanobacteria OTUs and revealed the dominance of the heterocystous genus Mastigocladus; however, the affiliations were less apparent using the 16S rRNA marker gene. The latter is likely due to the low number of sequences and sequenced genomes from the order Stigonematales in the databases. The Mastigocladus phylotypes were present throughout the temperature gradient (69 °C to near 38 °C), thereby expanding their upper temperature limit compared with the results of other thermal or laboratory systems (Finsinger et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2009). The 16S rRNA and nifH gene approach also identified members of the non-heterocystous Oscillatoriales (including both non-diazotrophs and diazotrophs), although they were present at a lower abundance; this group was not detected using the DGGE approach. Taken together, the data show that the Porcelana spring has a unique microbial composition devoid of unicellular cyanobacteria and other diazotrophic bacteria.

To broaden our knowledge of the importance of nitrogen fixation in the Porcelana spring, diel activities were examined using both the nitrogenase activity and 15N2 isotope uptake approaches; the use of these complementary techniques reflect different aspects of the fixation process (Peterson and Burris, 1976; Montoya et al., 1996). To date, measurements of cyanobacterial-associated nitrogenase activity (acetylene reduction assay) have dominated hot spring analyses (Steunou et al., 2006, 2008; Miller et al., 2009). Recent studies showed that heterotrophic bacteria and archaea may serve as significant nitrogen fixers in hot springs (Hamilton et al., 2011; Loiacono et al., 2012). However, the only study following 15N2 isotope uptake was conducted in 1970 in thermal microbial mats (YNP) dominated by the cyanobacterial genera Calothrix and Mastigocladus (Stewart, 1970). Nitrogen fixation assessed using nitrogenase activity in combination with 15N2 gas uptake provided different but complementary information; therefore, we used these techniques in the present study of the Porcelana hot spring. The data show that diazotrophy is the norm in this hot spring in all 4 years examined. Furthermore, the activity was only apparent during the day time (1300–1400 hours) and was highest at 58 °C to 46 °C but was not detected above 60 °C. The nitrogenase activity recorded was on a similar order of magnitude (50.0 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1) to that reported for the Mushroom Spring (YNP; 40–180 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1; Steunou et al., 2008), although there were differences in the retrieval of the diazotrophic biomass. Similarly, nitrogen fixation rates in the Porcelana hot spring (ranging from 2 to 8 nmol N cm−2 h−1) were in agreement with the activities reported for other non-thermal aquatic ecosystems (Fernandez et al., 2011). The data further demonstrated that the nitrogen fixation rates in the Porcelana microbial mat fell within the theoretical ratio for C2H4:N2 of 4:1 (if hydrogen production was taken into account; Postgate, 1982).

The use of the nifH gene as a potent molecular marker for diazotrophs in natural ecosystems has been extensive in recent years (Díez et al., 2007; Severin and Stal, 2009, 2010; Fernandez et al., 2011). However, the presence of nif genes or transcripts is not necessarily coupled to activity, as shown for Synechococcus-dominated hot spring mats (Steunou et al., 2006, 2008) where nifH gene expression peaked in the evening and nitrogenase activity peaked in the morning. A similar phenomenon was also observed in cyanobacterial microbial mats from temperate regions (Stal et al., 1984; Severin and Stal, 2009, 2010). In contrast, the nitrogen fixation activity (nitrogenase activity and N2 uptake) in the Porcelana hot spring showed a positive correlation with nifH gene expression. Moreover, because nitrogen fixation during the daytime is typical for ecosystems dominated by heterocystous cyanobacteria (Stal, 1995; Evans et al., 2000; Charpy et al., 2007; Bauer et al., 2008), our data infer the predominance, if not the exclusive role, of the heterocystous Mastigocladus-type cyanobacteria in nitrogen fixation in the Porcelana hot spring.

It cannot be excluded that the low concentrations of combined inorganic nitrogen (for example, ammonium and nitrate) in the Porcelana hot spring may be the result of a rapid turnover of these compounds (Herbert, 1999). However, the distinct nitrogen fixation activities recorded (on average 3 g N m−2 year) in the Porcelana hot spring suggest that this process is not diminished by other sources of combined nitrogen. Rather, we can conclude that the entry of ‘new' nitrogen by diazotrophic cyanobacteria supports most of the total daily nitrogen demand (up to 99%) of the microbial mat. Comparing this nitrogen input with that of rain water (ca. 0.1 g N m−2 per year) for the geographical region related to Porcelana (Weathers and Likens, 1997), we suggest that the biological nitrogen fixation found in our study may constitute the major source of ‘new' nitrogen into this ecosystem.

The fact that both the nitrogen and CO2 fixation coincided at mid-day in the Porcelana cyanobacterial mat may explain the substantial nitrogen fixation activity recorded. Photosynthesis would not only cover the high energy demand (ATP) of the nitrogen fixation process but also provide the required reducing power and carbon skeletons.

Conclusions

Our data demonstrate that the microbial mats covering the thermal gradient of the Porcelana hot spring outflow represent a well-organized and functioning ecosystem dominated by diazotrophic cyanobacteria of the Mastigocladus-type and may represent a typical scenario for neutral hot springs. Our results further emphasize the pivotal role of such diazotrophic cyanobacteria in maintaining this microbial dominated ecosystem by delivering most of its nitrogen demand through nitrogen fixation. These findings may also have important implications for other thermal or extreme environments dominated by cyanobacterial microbial mats.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff of the Huinay Scientific Field Station for making our visits to the Porcelana hot spring possible. We also thank Dr C Pedrós-Alió, and colleagues R MacKenzie, T Quiroz, S Guajardo and S Espinoza for their assistance with sample collection and analysis, and Dr S Andrade for his help with the analysis of the metal samples. This work was financially supported by PhD scholarship CONICYT No. 21110900, the French Embassy for PhD mobility (Chile) and LIA MORFUN (LIA 1035), and the following grants funded by CONICYT: FONDECYT No. 1110696 and FONDAP No. 15110009.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer K, Díez B, Lugomela C, Seppelä S, Borg AJ, Bergman B. (2008). Variability in benthic diazotrophy and cyanobacterial diversity in a tropical intertidal lagoon. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 63: 205–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B, Gallon JR, Rai AN, Stal LJ. (1997). N2 Fixation by non-heterocystous cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 19: 139–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bruland KW, Coale KH. (1985). Analysis of seawater for dissolved cadmium, copper, and lead: an intercomparison of voltammetric and atomic adsorption methods. Mar Chem 17: 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Capone DG. (1993). Determination of nitrogenase activity in aquatic samples using the acetylene reduction procedure. In: Kemp PF, Sherr BF, Sherr EB, Cole JJ (eds), Handbook of Methods in Aquatic Microbial Ecology. Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, pp 621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Charpy L, Alliod R, Rodier R, Golubic S. (2007). Benthic nitrogen fixation in the SW New Caledonia lagoon. Aquat Microb Ecol 47: 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KR. (1993). Non-parametric multivariate analysis of changes in community structure. Aust J Ecol 18: 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Cole JK, Peacock JP, Dodsworth JA, Williams AJ, Thompson DB, Dong H et al. (2013). Sediment microbial communities in Great Boiling Spring are controlled by temperature and distinct from water communities. ISME J 7: 718–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coman C, Druga B, Hegedus A, Sicora C, Dragos N. (2013). Archaeal and bacterial diversity in two hot spring microbial mats from a geothermal region in Romania. Extremophiles 17: 523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai MS, Assig K, Dattagupta S. (2013). Nitrogen fixation in distinct microbial niches within a chemoautotrophy-driven caves ecosystem. ISME J 7: 2411–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez B, Bauer K, Bergman B. (2007). Epilithic cyanobacterial communities of a marine tropical beach rock (Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef): diversity and diazotrophy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 3656–3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez B, Bergman B, Pedrós-Alió C, Anto M, Snoeijs P. (2012). High cyanobacterial nifH gene diversity in Arctic seawater and sea ice brine. Environ Microbiol 4: 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AM, Gallon JR, Jones A, Staal M, Stal LJ, Villbrandt M et al. (2000). Nitrogen fixation by Baltic cyanobacteria is adapted to the prevailing photon flux density. New Phytol 147: 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C, Farías L, Alcaman ME. (2009). Primary production and nitrogen regeneration processes in surface waters of the Peruvian upwelling system. Prog Oceanogr 83: 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C, Farías L, Ulloa O. (2011). Nitrogen fixation in denitrified marine waters. PLoS One 6: e20539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsinger K, Scholz I, Serrano A, Morales S, Uribe-Lorio L, Mora M et al. (2008). Characterization of true-branching cyanobacteria from geothermal sites and hot springs of Costa Rica. Environ Microbiol 10: 460–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JR, Mitchell KR, Jackson-Weaver O, Kooser AS, Cron BR, Crossey LJ et al. (2008). Molecular characterization of the diversity and distribution of a thermal spring microbial community by using rRNA and metabolic genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 4910–4922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton T, Lange R, Boyd E, Peters J. (2011). Biological nitrogen fixation in acidic high-temperature geothermal springs in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Environ Microbiol 13: 2204–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser A. (1989). Fuentes termales y minerales en torno a la carretera Austral, Regiones X–XI, Chile. Rev Geol Chile 16: 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert RA. (1999). Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol Rev 23: 563–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W, Wang S, Jiang H, Dong H, Briggs BR. (2013). A comprehensive census of microbial diversity in hot springs of Tengchong, Yunnan Province, China using 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing. PLoS One 8: 53350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Jiang H, Briggs BR, Wang S, Hou W, Li G et al. (2013). Archaeal and bacterial diversity in acidic to circumneutral hot springs in the Philippines. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 85: 452–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inskeep WP, Jay ZJ, Tringe SG, Herrgard MJ, Rusch DB, Metagenome YNP Project Steering Committee and Working Group Members. (2013). The YNP metagenome project: environmental parameters responsible for microbial distribution in the Yellowstone geothermal ecosystem. Front Microbiol 4: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatt C, Liu Z, Ludwig M, Kühl M, Jensen SI, Bryant DA et al. (2013). Temporal metatranscriptomic patterning in phototrophic Chloroflexi inhabiting a microbial mat in a geothermal spring. ISME J 7: 1775–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacap DC, Barraquio W, Pointing SB. (2007). Thermophilic microbial mats in a tropical geothermal location display pronounced seasonal changes but appear resilient to stochastic disturbance. Environ Microbiol 9: 3065–3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Klatt C, Wood JM, Rusch DB, Ludwig M, Wittekindt N et al. (2011). Metatranscriptomic analyses of chlorophototrophs of a hot-spring microbial mat. ISME Journal 5: 1279–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiacono S, Meyer-Dombard D, Havig J, Poret-Peterson A, Hartnett H, Shock E. (2012). Evidence for high-temperature in situ nifH transcription in an alkaline hot spring of Lower Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park. Environ Microbiol 14: 1272–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie R, Pedrós-Alió C, Díez B. (2013). Bacterial composition of microbial mats in hot springs in Northern Patagonia: Variations with seasons and temperature. Extremophiles 17: 123–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson L, Díez B, Wartiainen I, Zheng W, El-Shehawy R, Rasmussen U. (2009). Diazotrophic diversity, nifH gene expression and nitrogenase activity in a rice paddy field in Fujian, China. Plant Soil 325: 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Dombard DR, Shock EL, Amend JP. (2005). Archaeal and bacterial communities in geochemically diverse hot springs of Yellowstone National Park, USA. Geobiology 3: 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SR, Purugganan M, Curtis SE. (2006). Molecular population genetics and phenotypic diversification of two populations of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 2793–2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SR, Williams R, Strong AL, Carvey D. (2009). Ecological specialization in a spatially structured population of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus. Appl. Environ Microbiol 75: 729–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya JP, Voss M, Kahler P, Capone DG. (1996). A simple, high-precision, high-sensitivity tracer assay for N2 fixation. Appl Environ Microbiol 62: 986–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Fukui M. (2002). Phylogenetic characterization of microbial mats and streamers from a Japanese alkaline hot spring with a thermal gradient. J Gen Appl Microbiol 48: 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nübel U, Garcia-Pichel F, Muyzer G. (1997). PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 3327–3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JB, Steppe TF, Litaker RW, Paerl HW. (1998). N2 fixing microbial consortia associated with the ice cover of Lake Bonney, Antarctica. Microbiol Ecol 36: 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otaki H, Everroad R, Matsuura K, Haruta S. (2012). Production and consumption of hydrogen in hot spring microbial mats dominated by a filamentous anoxygenic photosynthetic bacterium. Microbes Environ 27: 293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RT, Ramsing NB, Bateson MM, Ward DM. (2003). Geographical isolation in hot spring cyanobacteria. Environ Microbiol 5: 650–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RB, Burris RH. (1976). Conversion of acetylene reduction rates to nitrogen fixation rates in natural populations of blue-green algae. Anal Biochem 73: 404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poly F, Monrozier LJ, Bally R. (2001). Improvement in the RFLP procedure for studying the diversity of nifH genes in communities of nitrogen fixers in soil. Res Microbiol 152: 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postgate JR. (1982) The Fundamentals of Nitrogen Fixation. Cambridge University Press: London. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell D, Sompong U, Yim LC, Barraclough TG, Peerapornpisal Y. (2007). The effects of temperature, pH and sulphide on the community structure of hyperthermophilic streamers in hot springs of northern Thailand. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 60: 456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimbault P, Garcia N. (2008). Evidence for efficient regenerated production and dinitrogen fixation in nitrogen-deficient waters of the South Pacific Ocean: impact on new and export production estimates. Biogeosciences 5: 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Severin I, Stal LJ. (2009). NifH expression by five groups of phototrophs compared with nitrogenase activity in coastal microbial mats. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 73: 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severin I, Stal LJ. (2010). Temporal and spatial variability of nifH expression in three filamentous cyanobacteria in coastal microbial mats. Aquat Microb Ecol 60: 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD, Westcott SL. (2011). Assessing and improving methods used in operational taxonomic unit-based approaches for 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 77: 3219–3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sompong U, Hawkins PR, Besley C, Peerapornpisal Y. (2005). The distribution of cyanobacteria across physical and chemical gradients in northern Thailand. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 52: 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stal LJ, Grossberger S, Krumbein WE. (1984). Nitrogen fixation associated with the cyanobacterial mat of a marine laminated microbial ecosystem. Mar Biol 82: 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Stal LJ. (1988). Nitrogen fixation in cyanobacterial mats. In: Packer L, Glazer AN (eds). Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, pp 474–484. [Google Scholar]

- Stal LJ. (1995). Physiological ecology of cyanobacteria in microbial mats and other communities. New Phytol 131: 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steunou AS, Bhaya D, Bateson MM, Melendrez M, Ward D, Brecht E et al. (2006). In situ analysis of nitrogen fixation and metabolic switching in unicellular thermophilic cyanobacteria inhabiting hot spring microbial mats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 2398–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steunou AS, Jensen SI, Brecht E, Becraft ED, Bateson MM, Kilian O et al. (2008). Regulation of nif gene expression and the energetics of N2 fixation over the diel cycle in a hot spring microbial mat. ISME J 2: 364–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart G, Fitzgerald P, Burris RH. (1967). In situ studies on N2 fixation using the acetylene reduction technique. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 58: 2071–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart W. (1970). Nitrogen fixation by blue-green algae in Yellowstone thermal areas. Phycologia 9: 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Hou W, Dong H, Jiang H, Huang L. (2013). Control of temperature on microbial community structure in hot springs of the Tibetan Plateau. PLoS One 8: e62901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DM, Ferris MJ, Nold SC, Bateson MM. (1998). A natural view of microbial biodiversity within hot spring cyanobacterial mat communities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62: 1353–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DM, Castenholz RB. (2000). Cyanobacteria in geothermal habitats. In: Potts M, Whitton B (eds), Ecology of Cyanobacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers: The Netherlands, pp 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers KC, Likens GE. (1997). Clouds in Southern Chile: an important source of nitrogen to nitrogen-limited ecosystems? Environ Sci Technol 31: 210–213. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.