Abstract

Aim:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate how increasing NaCl salinity in the medium can affects the essential oils (EOs) composition and phenolic diterpene content and yield in leaves of Salvia officinalis L. The protective role of such compounds against NaCl stress was also argued with regard to some physiological characteristics of the plant (water and ionic relations as well as the leaf gas exchanges).

Materials and Methods:

Potted plants were exposed to increasing NaCl concentrations (0, 50, 75, and 100 mM) for 4 weeks during July 2012. Replicates from each treatment were harvested after 0, 2, 3, and 4 weeks of adding salt to perform physiological measurements and biochemical analysis.

Results:

Sage EOs were rich in manool, viridiflorol, camphor, and borneol. Irrigation with a solution containing 100 mM NaCl for 4 weeks increased considerably 1.8-cineole, camphor and β-thujone concentrations, whereas lower concentrations (50 and 75 mM) had no effects. On the contrary, borneol and viridiflorol concentrations decreased significantly under the former treatment while manool and total fatty acid concentrations were not affected. Leaf extracts also contained several diterpenes such as carnosic acid (CA), carnosol, and 12-O-methoxy carnosic acid (MCA). The concentrations and total contents of CA and MCA increased after 3 weeks of irrigation with 75 or 100 mM NaCl. The 50 mM NaCl had no effect on these diterpenes. Our results suggest a protective role for CA against salinity stress.

Conclusion:

This study may provide ways to manipulate the concentration and yield of some phenolic diterpenes and EOs in sage. In fact, soil salinity may favor a directional production of particular components of interest.

KEY WORDS: Antioxidants, carnosic acid, essential oil quality, plant nutrition, salinity

INTRODUCTION

High demand for natural products such as essential oils (EOs) and phenolic diterpenes has fuelled the increased interest in the cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) as alternatives to traditional crops. The cultivation of EOs-containing species from different families has been initiated in a number of countries to respond to food and cosmetic industry needs. Common sage (Salvia officinalis) is among several Lamiaceae species, which received much interest [1-3]. The main sage oil-producing countries in the Mediterranean basin are Spain, France, and Tunisia [4]. Still, growing such species under arid and semi-arid conditions is a big duty. For instance, abiotic stresses such as heat, water shortage, and salinity, apart from restricting the growth and yield, provoke various metabolic changes in most plants [2,5,6]. All the above abiotic factors result in a build-up of salt in the soil imposing a major limitation to the growth and yield of crops. Although there is a substantial literature on the behavior of common species under stressful conditions [5], data on MAPs are less available.

Common sage is a Mediterranean shrub of the Lamiaceae family, which has been used for a long time as food spice and folk medicine. The biological properties of EO of sage are attributed mainly to α- and β-thujone, camphor, and 1.8-cineole [7]. Still the percentage of these EOs depends on several factors including the geographic origin of the plant, environmental factors, plant organ, and genetic differences [8]. Apart from volatiles and flavonoids, sage contains the relatively large amount of polyphenolic compounds with antioxidant activity [9,10]. Carnosic acid (CA), 12-O-methyl carnosic acid (MCA) and carnosol (CAR) were shown to be the major diterpene constituents in leaves of both sage and rosemary [9]. CA metabolism plays a double role in several Labiatae plants. First, CA can protect plants from biotic and abiotic stresses by scavenging free radicals within the chloroplasts. Second, CA metabolism may also play a role in the stability of cell membranes [11]. In addition, CA and its derivatives have a wide range of pharmacological and biological activities. These compounds are responsible for up to 90% of the antioxidant activity of the plant extract [12,13], so there is an increasing interest in using sage as a source of natural antioxidants in food preservatives. Besides, CA and CAR were found to possess antibacterial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, anti-obesity, and photoprotective activities [10,14,15]. Recent reports have showed that these compounds may be useful for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases [16]. Such biological and commercial potential of the sage diterpenes makes them an attractive target for developing strategies intended for their extensive production [17]. Besides, the extraction of these compounds from plants needs sufficient plant biomass together with high amounts of these metabolites. In this regard, several studies [18-20] have targeted enhancing the production of these high-value plant compounds by choosing the accurate plant species or accession, the richest plant part or the proper plant development stage. Besides, the use of some agricultural techniques has been also reported [20]. It was shown, for instance, that the essential cations (K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ and Fe2+) can favor the foliar biosynthesis of several phenolic diterpenes in both sage and rosemary [2,20]. As well, it was shown that the upper young leaves contained higher levels of diterpenes when compared to bottom senescent ones [20]. Furthermore, it has been shown that drought-induced oxidative stress reduces the CA and CAR contents of the sage leaves and enhances the formation of the highly oxidized diterpenes isorosmanol (ISO) and dimethyl isorosmanol [12]. Still, the effects of moderate and severe NaCl salinity stress on the biosynthesis of such high-value plant compounds are not well studied.

In several countries, water shortages have forced growers to use more and more treated wastewater and saline water for plant irrigation. The soil and water salinity possess serious limitation to plant productivity. Crops are more and more exposed to this problem accentuated by increasing climate aridity. Plants exposed to relatively high concentrations of salt undergo several changes in their metabolism in order to cope with their stressful environment. For instance, excessive soil salinity alters EOs biosynthesis and composition in several species of industrial interest [6,21,22]. The impact of salinity on the EO yield and composition was studied on sage’s fruits in hydroponic culture [1] or with relatively low level of NaCl in the soil (lower than 4.7 dS/m) [3]. Still the effect of moderate and higher NaCl concentrations in the soil on the EOs composition and phenolic diterpenes are not well studied on the common sage. It is, therefore, of interest to evaluate if irrigation with increasing saline water can be used as an agricultural technique to increase their foliar concentrations in sage. The protective role of CA against NaCl stress was also argued with regard to some physiological features of the plant (water and ionic relations as well as the photosynthetic exchanges).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Culture

Common sage used in the present study was propagated by cuttings at the floral budding stage. Sixty-four plants (1-year-old) were grown in 5 L plastic pots containing desert dune sand (≤1 mm in diameter, 0.1 g soluble salt 100/g DW of sand) in a glasshouse covered with a shade net. The experiment was carried out during July 2012. Plants were exposed, in average, to a PPFD of 1000 mmol/m/s. During 3 weeks after transplanting into the pots, all plants were irrigated with a complete nutrient solution having an initial total ion concentration of 4.5 mM and electrical conductivity (EC) of 3.0 dS/m. These plants were divided into two batches: For the first batch (kinetic batch), forty-eight plants (48) have received increasing NaCl concentrations (0, 50, 75, and 100 mM) in the irrigation solution. The resulted soil ECs were, respectively, 3.0, 9.0, 11.1, and 14.9 dS/m. To avoid osmotic shock, NaCl concentrations were increased gradually, by 25 mM/day, until the desired concentration was reached. Each solution was used to irrigate twelve pots every 4 days. Four plants were randomly harvested from each treatment after 2, 3, and 4 weeks of adding NaCl. The experimental design was a completely randomized block with 4 replicates (each pot being a replicate). This batch of plants was used to determine the effect of salinity on total leaf dry weight, the water content (WC), and the kinetic of accumulation of the phenolic abietanes diterpenes and their yields. The second batch of plants was used to determine the effect of increasing salinity on EOs composition, ion contents, and plant gas exchange. Sixteen plants were irrigated with the same NaCl as mentioned above and were harvested only at the end of the treatment.

Determination of Plant Growth and WC

Plants (4 replicates for each treatment) were randomly harvested after 0, 2, 3, and 4 weeks of adding salt to determine plant growth and leaf WC. After recording their total leaf fresh biomass (FW), they were oven-dried at 80°C for 48 h and total leaf dry biomass (DW) was measured. Plant growth was estimated by determining the total dry weight of the leaves. The leaf WC was determined as follow:

WC = FW−DW/DW

Ion Contents and Gas Exchange Measurements

Ion contents and gas exchange were performed on fully expanded leaves collected between 9 and 11 am after 4 weeks of NaCl treatment. These evaluations were completed with an infrared, portable CO2 gas analyzer (ADC, BioScientific Ltd., Hoddesdon, UK). The photosynthetic rate (A), transpiration (E), and stomatal conductance (gs) were all evaluated. The instantaneous water use efficiency (iWUE) was calculated as A/E.

EOs Extraction and Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analyses

EOs analyses were performed on leaves collected between 9 and 11 am after 4 weeks of treatment. The EOs were extracted from 10 g sub-samples of fresh leaves by steam distillation at atmospheric pressure, using a modified Clevenger type apparatus. Distillation lasted 3 h. The EOs were separated from the aqueous phase by adding chloroform. The organic layer was dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated under atmospheric pressure to eliminate the chloroform. The residue was solubilized in 30 volumes of 100% (v/v) hexane and analyzed by GC/MS as described by Tounekti et al. [6].

Abietanes Diterpenes Analyses

For the abietanes diterpenes analyses, a sub-sample of fresh leaves was taken from each harvested plant. The leaves were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis. Diterpenes were determined as described by Munné-Bosch et al. [12].

Statistical Analyses

Variance of data was analyzed with a two-way ANOVA (salt concentration and duration of treatment being the independent variables) using a GLM procedure of SAS software 1996 for a Randomized Complete Block design with 4 replicates. To correct for departure from normality, EOs data (percentages) were Log-transformed before analyses; untransformed means were reported. Where applicable, means were separated by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (P ≤ 0.05).

RESULTS

Growth, Water Relations, Ionic Contents, and Gas Exchanges in Salt-stressed Sage Plants

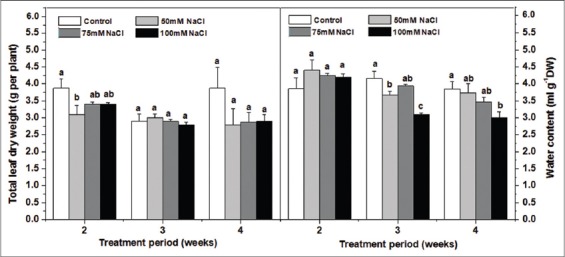

The present results revealed that soil salinity had no significant effect on total leaf dry weight per plant [Figure 1]. Still such growth parameter tended to decrease after 4 weeks in all salt treatments. Furthermore, the lower NaCl levels (50 and 75 mM) have not affected noticeably the leaf WC either after 4 weeks of treatment. However, a significant decrease was seen for the 100 mM NaCl treatment starting from the 3rd week [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Effect of increasing soil NaCl concentrations (mM) on foliar water content (ml (H2O) g−1 Dry weight) and total leaves dry weight (g per plant) in Salvia officinalis L plants. Each value is the mean of 3 replicates ± standard deviation. Values marked by different small letters are significantly different at P < 5%

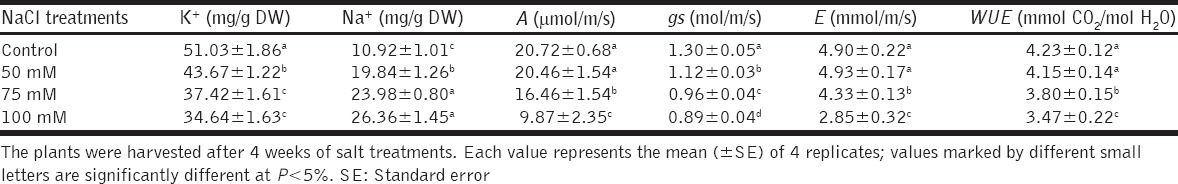

After 4 weeks soil salinity has led to a significant decrease in the assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration rate (E) and therefore the instantaneous water use efficiency (iWUE) mainly for 75 and 100 mM treatments [Table 1]. The largest decreases were shown at 100 mM NaCl, leading to A values of 10 µmol/m/s after 4 weeks of stress which was 50% lower than control plants. Besides, our results demonstrate that gs decreased significantly more than A in all salt treatments and mainly when the lowest NaCl concentrations were provided, which suggests a stomatal limitation of the photosynthetic capacity mainly after 4 weeks of treatments. After the same period, salinity has strongly increased Na+ and reduced the K+ content in the sage leaves, with the 100 mM dose causing the largest effect. For instance, the leaf Na+ contents increased by 140% and the K+ contents decreased by 32% in the 100 mM-treated plants relative to controls [Table 1].

Table 1.

Ions contents, net photosynthesis (A), stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration rate (E), and instantaneous water use efficiencies (iWUE=A/E) in leaves of sage plants grown in a medium without NaCl (control), or containing increasing NaCl concentrations (0, 50, 75 and 100 mM)

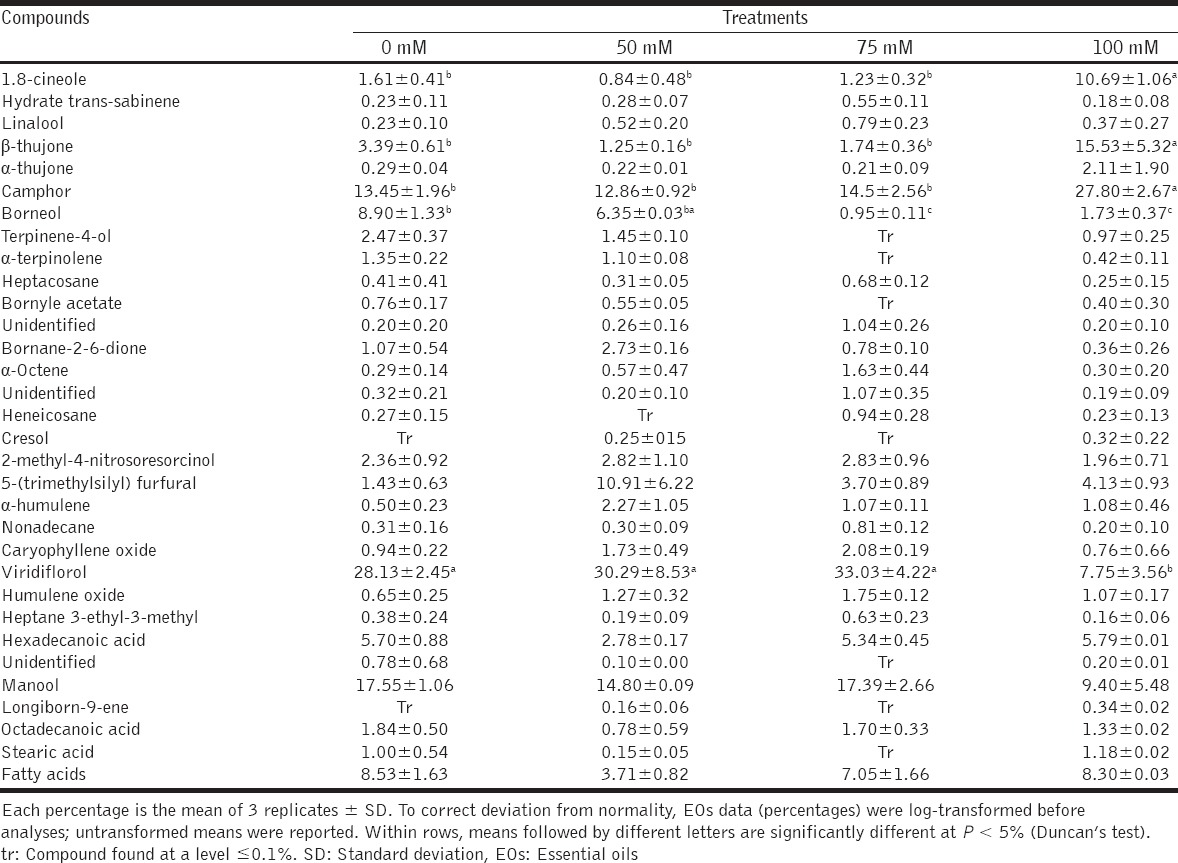

Salt Stress-induced Changes in EOs

The GC-MS analyses of sage EOs obtained by steam distillation of leaves allowed the identification of 31 compounds representing about 96% of the total EOs [Table 2]. The oil contained different chemical classes such as monoterpenes (24%), sesquiterpenes (29%), diterpenes (19%), saturated fatty acids (23.6%), and alkanes (1.3%). The majority of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes recovered were oxygen-containing compounds. The most abundant were viridiflorol (28.1%), manool (17.5%), camphor (13.4%), borneol (8.9%), and β-thujone (3.4%). The analyses also revealed a relatively large fraction made of saturated fatty acids [Table 2]. The increased concentration of NaCl in the soil medium changed the composition of sage EOs but did not induce the synthesis of new oils. These changes depended on salt concentration. 1.8-cineole, β-thujone and camphor increased considerably in the plants fed with 100 mM NaCl; lower salt concentrations had no effect. In contrast, borneol and viridiflorol levels were reduced by the 100 mM NaCl treatment. Manool and total fatty acid fraction did not change [Table 2].

Table 2.

Leaf EOs composition (% of total) in Salvia officinalis L. after 4 weeks of culture on increasing NaCl concentrations

Salt Stress-induced Changes in Phenolic Diterpenes

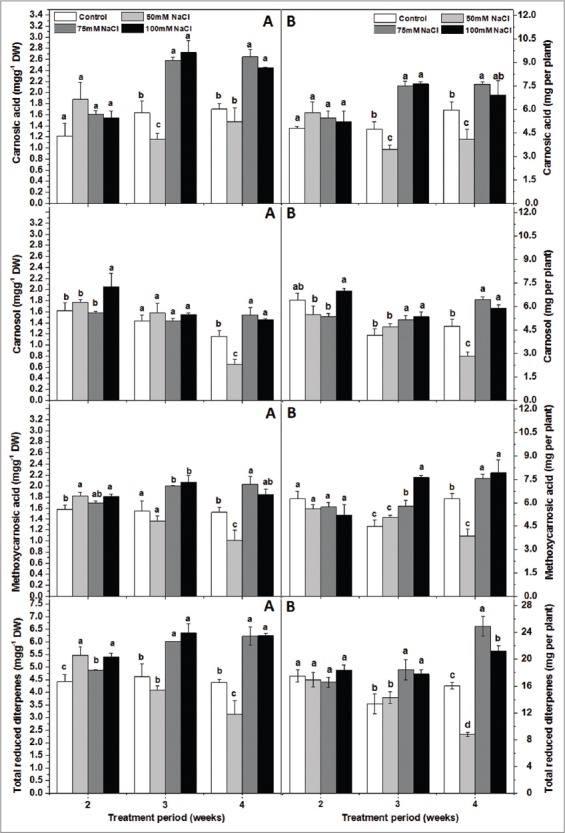

In common sage, CA and CAR are the major phenolic diterpenes in the leaves [Figure 2]. Our results demonstrated that the CA content varied between 1.2 and 1.7 mg/g DW and CAR between 1.2 and 1.6 m/g DW in the leaves of control plants. We found that NaCl in the soil medium did not affect significantly the oxidized diterpenes rosmanol (ROS) and dimethyl isorosmanol (DIM) as well as their total contents regardless of the duration of the treatment [Table 3]. Whereas, the effect of salinity on CA, CAR, MCA, ISO, and the total reduced diterpene contents changed with time (treatment x duration significant). After 2 weeks of treatment, NaCl had only a limited effect on sage abietane diterpene content. However, after 3 weeks, plants fed with 75 mM or 100 mM NaCl had considerably more CA, MCA and reduced forms in their leaves than those fed with 0 mM or 50 mM NaCl [Figure 2]. After 4 weeks, plants which received 75 mM or 100 mM NaCl contained more CA, MCA, and CAR than those irrigated with 50 mM. The latter had similar CA but lower MCA and CAR content than control plants. The reduced diterpenes content tended to decrease when plants were fed with 50 mM NaCl and to increase for higher concentrations (after 3 or 4 weeks). Still, the levels of the oxidized compounds did not change significantly in the 50 and 75 mM-treated plants of the present study. Higher salt concentrations enhanced CA, MCA, and CAR biosynthesis [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Effect of increasing soil NaCl concentrations (mM) on foliar reduced diterpene concentrations (mg/g Dry weight) (A) and contents (mg per plant) (B) in Salvia officinalis L plants. CA: Carnosic acid, CAR: Carnosol, MCA: Methoxycarnosic acid; RED: Total reduced diterpenes (RED = CA + CAR + MCA). Each concentration is the mean of 4 replicates ± standard deviation. In values marked by different small letters are significantly different at P < 5%

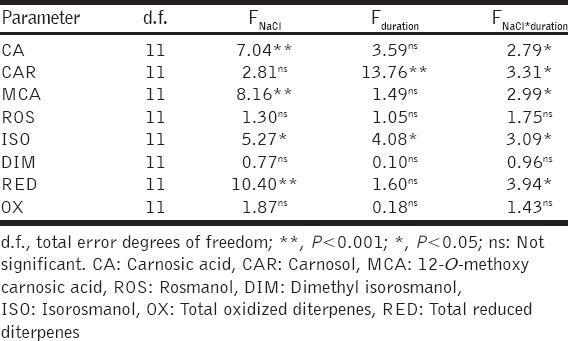

Table 3.

Summary of two-way ANOVA of effects of growth medium NaCl concentration and treatment duration as fixed independent variables

DISCUSSION

In all plant species, salinity leads to a reduction in plant biomass when it exceeds a certain threshold [5]. According to Maas and Hoffman [23], a crop is considered moderately salt sensitive when 50% of the reduction in biomass occurred at 90 mM NaCl, which is not the case for sage plant as revealed by our results. In fact, despite its trend for decreasing, for all NaCl applied levels, at the treatment end, total leaf dry weight per plant was not significantly affected by soil salinity [Figure 1]. Hence, the present study confirms that sage is a moderately salt-resistant glycophyte [2,23]. The detrimental effects of NaCl on plants are typically due to osmotic effects and/or ionic imbalances resulting from nutritional deficiency or excess ions [20,24,25]. The abscission of the oldest leaves, and therefore the slight decrease of the total leaf dry weight (either not statistically significant), has been considered an adaptive mechanism that prevents the accumulation of toxic ions (Na+ and Cl−) and reduces water loss in salt-stressed plants [5,24,25]. According to our results, the application of the 50 mM NaCl in the soil did not affect noticeably the leaf WC either after 4 weeks of treatment, while at higher levels plants were unable to suitably hydrate their tissues which cause water stress [6,24,25]. As a consequence, salinity has led to an early decrease in the assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (gs), and the transpiration rate (E) [Table 1], as it was seen in several other species [20,24]. Still the largest decreases were shown for the higher NaCl levels. Such simultaneous decrease in gs and E has kept away the salt-stressed plants from an acute loss of the leaf cell turgor. To maintain leaf cell turgor, plants generally accumulate solutes from the soil (Na+ and Cl−) [24]. According to our results, after 4 weeks of treatment, the Na+ increased by 140% and the K+ decreased by 32% in the 100 mM NaCl-treated plants relative to controls, while the effects were more moderate in the 75 and 50 mM-treated plants. Still, this increased uptake of Na+ (inclusion mechanism), combined with a limited production of new leaves, led to a build-up of Na+ to toxic levels, which likely caused the leaf senescence and abscission.

The response of sage to changes in its environment involves among others the regulation of the levels of its secondary metabolites including EOs and phenolic diterpenes [2,3,12,26]. The effect of salinity on isoprenoids biosynthesis is expected as it affects the photosynthetic assimilation (A) and, therefore, the glycolysis pathway from where their precursor, D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and pyruvate, were provided. It was already found that adding 100 mM NaCl to the plant growing medium almost increased concentrations and contents of several abietane diterpenes in rosemary leaves [20]. Herein we test for the first time to our knowledge the effect of increasing NaCl concentrations on the leaf abietanes diterpenes yield and composition in the sage plant.

The GC-MS analyses of sage EOs obtained by steam distillation of leaves allowed the identification of 31 compounds representing about 96% of the total EOs [Table 2]. The most abundant oils were viridiflorol (28.1%), manool (17.5%), camphor (13.4%), borneol (8.9%), and β-thujone (3.4%); this composition is somewhat similar to that of Eastern Lithuanian sage (i.e. 9.3-35.6% α-thujone; 6.9-29.1% camphor; 6-24% viridiflorol; 3.1-13.6% α-humulene; 3-13.3% manool; 8.6-12.7% 1.8-cineole, and 2-5.5 % borneol) [27,28]. The relatively high levels of oxygenated compounds mainly thujones, 1.8-cineole and camphor confer to the sage EO its antiseptic, astringent, carminative, and antispasmodic values. Still lesser concentrations of 1.8-cineole, camphor, and borneol were recorded herein as compared to our earlier studies, which may be due to seasonal variations, cultivar diversity or plant age [29]. For example, the low camphor levels found in this study seems to be due at least to the fact that the bulk of the leaves used were mature. Many studies showed that camphor is used in the recovery and recycling mechanisms for the carbon and energy accumulated during leaf development [30]. The analyses also revealed a relatively large fraction made of saturated fatty acids. This fraction was found in the extracts of many Lamiaceae species mainly in the genus Salvia [31-33].

As many other abiotic stresses, soil salinity can increase the synthesis of some secondary metabolites and encourage the formation of new compounds [34,35]. In agreement with this, our results showed that increasing NaCl in the soil medium changed the composition of sage Eos, but did not induce the synthesis of new oils. These changes depended on NaCl levels applied into the soil. For instance, 1.8-cineole, β-thujone and camphor increased considerably in the plants fed with 100 mM NaCl; lower salt concentrations had no effect. In contrast, borneol and viridiflorol levels were reduced by the 100 mM NaCl treatment. Manool and total fatty acid fraction did not change. Similarly, Hendawy et al. [36] reported that sage plants fed with NaCl (2500 ppm) in combination with different zinc concentrations had higher β-thujone, camphor and 1.8-cineole concentrations, less viridiflorol, and no manool. In the same way, Aziz et al. [3] have reported that increasing NaCl up to 4.7 dS/mimproved the α-thujone, cis-thujone and camphor contents. They also found that 1.8-cineole decreased and viridiflorol increased which is different to our results. The lower NaCl level they used could explain these differences since the percentage of some EO compounds are dependent on the medium salinity among others [6,35]. Besides, the effects of NaCl on the EO composition vary between species. For example the 50 mM NaCl applied during 3 weeks, increased 1.8-cineole, borneol and camphor in coriander leaves; while higher concentrations decreased these monoterpenes [35], which is not the case for sage as shown by the present results. The 1.8-cineole and camphor were also stimulated in two Ocimum varieties subject to an excess of water (125% of field capacity) or to a water deficit (75 and 50% of field capacity) [37]. NaCl appears to affect the activity of key enzymes in the biosynthesis pathways of EOs which concentrations are altered by salinity [38,39]. According to Putievsky et al. [40], good quality sage oil should contain a high percentage (>50%) of the epimeric α- and β-thujones and a low percentage (<20%) of camphor. Still more recent studies have stated that the biological properties of the sage’s EO are attributed mainly to α- and β-thujone, camphor, and 1.8-cineole [7]. It appeared, therefore, that the soil salinity has beneficial effects on the sage’s EO quality.

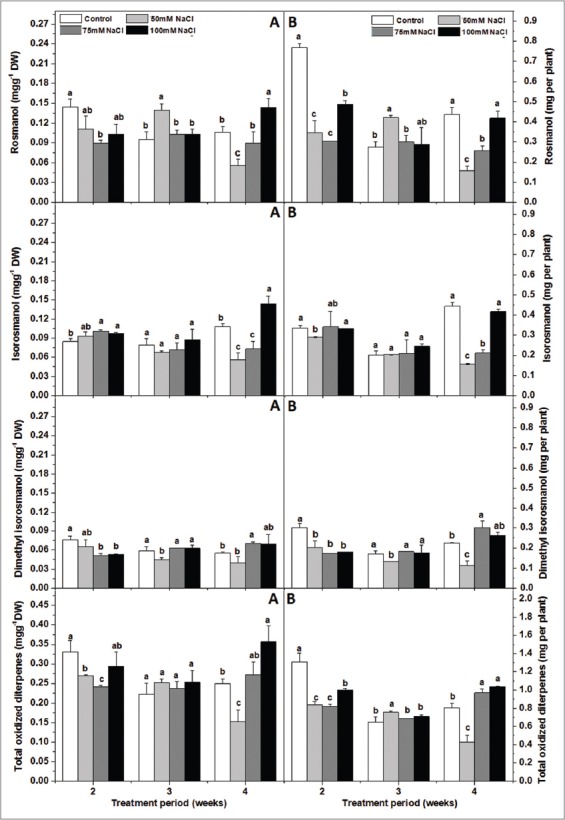

In common sage, CA and CAR are the major phenolic diterpenes in the leaves [Figure 2]. Dried sage leaves can contain up to 3% CA, depending on the plant variety, the growth conditions, the sample treatment and the method of preparing the extract. According to our results, the CA content varied between 1.2 and 1.7 mg/g DW and CAR between 1.2 and 1.6 mg/g DW in the leaves of control plants. Still our result agreed that environmental constraints produce substantial differences in flavonoid and phenolic acids and esters within plants particularly members of the Lamiaceae family [12,41,42]. We found that NaCl in the soil medium did not affect significantly the oxidized diterpenes ROS and DIM as well as their total contents regardless of the duration of the treatment [Table 3]. Whereas, the effect of salinity on CA, CAR, MCA, ISO, and the total reduced diterpene contents changed with time (treatment × duration significant) [Table 3]. After 2 weeks of treatment, NaCl had only a limited effect on sage diterpene content. However, after 3 weeks, plants fed with 75 or 100 mM NaCl had considerably more CA, MCA, and reduced forms in their leaves than those fed with 0 or 50 mM NaCl [Figure 2]. After 4 weeks, plants which received 75 or 100 mM NaCl contained more CA, MCA, and CAR than those irrigated with 50 mM. The latter had similar CA, but lower MCA and CAR content than control plants. Therefore, the NaCl-induced changes in leaf CA, MCA, and the total reduced diterpene composition depended more on stress intensity (concentration of salt in the irrigation solution); but, variability in CAR content is better explained by treatment duration. Still most isoprenoids and phenolic diterpenes are induced to protect plant cells from drought, salt, heat stress or mechanical wounding [2,39,43]. The tendency of the reduced diterpenes content to decrease when plants were fed with 50 mM NaCl and to increase for higher concentrations (after 3-4 weeks), suggests that the plants reacted differently to these two ranges of salinity. It appears that the 50 mM NaCl treatment induced only a mild osmotic stress, which caused the degradation (oxidation) of the normally occurring pools of reduced diterpenes. Still, the levels of the oxidized compounds did not change significantly in the 50 and 75 mM-treated plants of the present study, thus further supporting the view that plants can withstand photooxidative stress at these salinity levels. Whereas, higher salt concentrations, led to a more acute stress (oxidative or Na+ or Cl− toxicity) to which plants responded with enhanced CA, MCA and CAR biosynthesis [Figure 2]. In the latter situation, de novo biosynthesis of reduced diterpenes exceeded their degradation to oxidized forms. This appears especially true for the 100 mM NaCl-treated plants whose leaves had high concentrations of oxidized diterpenes basically at the 14th week [Figure 3]. It is already known that CA may give rise to CAR after enzymatic dehydrogenation or to highly oxidized diterpenes such as ROS or ISO after enzymatic dehydrogenation and free radical attack [9,12,42]. Thus, CA may function as a “cascading” antioxidant, in which oxidation products are further oxidized, thus improving antioxidative protection by CA. In addition, CA can be O-methylated to form MCA. The O-methylated diterpenes can reinforce and stabilize the lipid chain [42]. Another indication that the 100 mM-treated plants faced different type of stress compared to the lower-treated plants is the decrease of the leaf WC especially on the 14th week [Figure 1] meaning that their ability for osmotic adjustment decreased. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that the gs decreased significantly more than A in all salt treatments and mainly at 50 mM NaCl, which suggests a stomatal limitation of the photosynthetic capacity (restriction of CO2 availability for carboxylation). However, at higher concentrations mainly at 100 mM NaCl and apart from a stomatal limitation of photosynthesis, the plants suffered from a reduction in the iWUE and more acute stress, which could harm the photosynthetic apparatus [24,25]. These findings are in agreement with previous results that found that the increase in salinity levels decreased iWUE in tomato plants [44]. Under these conditions, the formation of reactive oxygen species can occur, which possibly leads to photoinhibition and/or photo-oxidative impairment. Besides, the effect of 50 mM NaCl on CA, MCA, and CAR resembles that of drought- or high light-induced oxidative stress conditions, which reduced their concentrations in rosemary leaves [12].

Figure 3.

Effect of increasing soil NaCl concentrations (mM) on foliar oxidized diterpene concentrations (mg/g Dry weight) (A) and contents (mg per plant) (B) in Salvia officinalis L plants. ROS: Rosmanol, ISO: Isorosmanol, DIM: Dimethyl isorosmanol, OX: Total oxidized diterpenes (OX = ROS + ISO + DIM). Each concentration is the mean of 4 replicates ± standard deviation. In values marked by different small letters are significantly different at P < 5%

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, NaCl in the soil medium affected EOs composition of common sage leaves by stimulating biosynthesis pathways of several monoterpene families such as p-menthane (1.8-cineole) and bornane (camphor). The increased concentration of 1.8-cineole under NaCl stress should enhance the commercial value of sage EOs [45] since 1.8-cineole and thujone are the main parameters of sage oil quality [46]. In addition, NaCl decreased borneol and the sesquiterpene viridiflorol. Still, our study provides ways to manipulate the concentration of phenolic diterpenes in sage leaves. We have shown that sage plant subjected to increasing NaCl concentrations (>50 mM) in the medium had higher CA and MCA content, but slightly lower total leaf dry mass compared to non-treated plants. Therefore, it may be possible to obtain higher yields of antioxidants, such as CA, from plants grown with saline water. It may be feasible to increase the commercial value of sage leaf extracts by manipulating the concentration of phenolic diterpenes and EOs. Nevertheless, larger scale field studies are needed to ascertain the potentially beneficial effects of NaCl on phenolic diterpene and EOs concentration against the potential loss in plant biomass production and soil fertility in the long run.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Support for the research of T. Tounekti was provided by the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) through the postdoctoral grant 83/TUN/D33. The authors are grateful to Dr. Sergi Munné-Bosch of the University of Barcelona for his scientific helps and support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ben Taarit M, Msaada K, Hosni K, Hammami M, Kchouk ME, Marzouk M, et al. Plant growth, essential oil yield and composition of sage (Salvia offcinalis L.) fruits cultivated under salt stress conditions. Ind Crop Prod. 2009;30:333–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tounekti T, Munné-Bosch S, Vadel AM, Chtara C, Khemira H. Influence of ionic interactions on essential oil and phenolic diterpene composition of Dalmatian sage (Salvia officinalis L.) Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:813–21. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aziz EE, Sabry RM, Ahmed SS. Plant growth and essential oil production of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) and curly-leafed parsley (Petroselinum crispum ssp crispum L.) cultivated under salt stress conditions. World Appl Sci J. 2013;28:785–96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung AY, Foster S. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley &Sons, Inc; 1996. Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients Used in Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chnnusamy V, Jagendorf A, Zhu J. Understanding and improving salt tolerance in plants. Crop Sci. 2005;45:437–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tounekti T, Vadel AM, Bedoui A, Khemira H. NaCl stress affects growth and essential oil composition in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2008;83:267–73. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raal A, Orav A, Arak E. Composition of the essential oil of Salvia officinalis L. from various European countries. Nat Prod Res. 2007;21:406–11. doi: 10.1080/14786410500528478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry NB, Anderson RE, Brennan NJ, Douglas MH, Heaney AJ, McGimpsey JA, et al. Essential oils from dalmatian sage (Salvia officinalis l.): Variations among individuals, plant parts, seasons, and sites. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:2048–54. doi: 10.1021/jf981170m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwarz K, Ternes W. Antioxidative constituents of Rosmarinus officinalis and Salvia officinalis : I. isolation of carnosic acid and formation of other phenolic diterpenes. Z Leben Unters Forsch. 1992;195:99–103. doi: 10.1007/BF01201766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brückner K, Božic D, Manzano D, Papaefthimiou D, Pateraki I, Scheler U, et al. Characterization of two genes for the biosynthesis of abietane-type diterpenes in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) glandular trichomes. Phytochemistry. 2014;101:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munné-Bosch S, Alegre L. Subcellular compartmentation of the diterpene carnosic acid and its derivatives in the leaves of rosemary. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1094–102. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munné-Bosch S, Schwarz K, Alegre L. Enhanced formation of alpha-tocopherol and highly oxidized abietane diterpenes in water-stressed rosemary plants. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:1047–052. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorsen MA, Hildebrandt KS. Quantitative determination of phenolic diterpenes in rosemary extracts. Aspects of accurate quantification. J Chromatogr A. 2003;995:119–25. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)00487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paris A, Strukelj B, Renko M, Turk V, Pukl M, Umek A, et al. Inhibitory effect of carnosic acid on HIV-1 protease in cell-free assays [corrected] J Nat Prod. 1993;56:1426–30. doi: 10.1021/np50098a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rau O, Wurglics M, Paulke A, Zitzkowski J, Meindl N, Bock A, et al. Carnosic acid and carnosol, phenolic diterpene compounds of the labiate herbs rosemary and sage, are activators of the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Planta Med. 2006;72:881–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-946680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischedick JT, Standiford M, Johnson DA, Johnson JA. Structure activity relationship of phenolic diterpenes from Salvia officinalis as activators of the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 pathway. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:2618–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tounekti T, Munné-Bosch S. Enhanced phenolic diterpenes antioxidant levels through non-transgenic approaches. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2012;31:505–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.del Baño MJ, Lorente J, Castillo J, Benavente-García O, del Río JA, Ortuño A, et al. Phenolic diterpenes, flavones, and rosmarinic acid distribution during the development of leaves, flowers, stems, and roots of Rosmarinus officinalis. Antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4247–53. doi: 10.1021/jf0300745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abreu ME, Muller M, Alegre L, Munne-Bosch S. Phenolic diterpenes and a-tocopherol contents in leaf extracts of 60 Salvia species. J Sci Food Agric. 2008;88:2648–53. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tounekti T, Vadel AM, Ennajeh M, Khemira H, Munné-Bosch S. Ionic interactions and salinity affect monoterpene and phenolic diterpene composition in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2011;174:504–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Keltawi NE, Croteau R. Salinity depression of growth and essential oil formation in spearmint and marjoram and its reversal by foliar applied cytokinin. Phytochemistry. 1987;26:1333–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heuer B, Yaniv Ravina I. Effect of late salinization of chia (Salvia hispanica), stock (Matthiolatri cuspidata) and evening primrose (Oenothera abiennis) on their oil content and quality. Ind Crop Prod. 2002;15:162–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maas EV, Hoffman GJ. Crop salt tolerance - current assessment. J Irrigation Drainage Div ASCE. 1977;103:115–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delfine S, Alvino A, Villani MC, Loreto F. Restrictions to carbon dioxide conductance and photosynthesis in spinach leaves recovering from salt stress Plant Physiol. 1999;119:1101–6. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loreto F, Centritto M, Chartzoulakis K. Photosynthetic limitations in olive cultivars with different sensitivity to salt stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26:595–601. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben Taarit M, Msaada K, Hosni K, Marzouk B. Changes in fatty acid and essential oil composition of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) leaves under NaCl stress. Food Chem. 2010;9:951–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maric S, Maksimovic M, Milos M. The impact of the locality altitudes and stages of development on the volatile constituents of Salvia officinalis L. from Bosnia and herzegovina. J Essent Oil Res. 2006;18:178–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernotiene G, Nivinskiene O, Butkiene R, Mockute D. Essential oil composition variability in sage (Salvia officinalis L.) Chemija. 2007;18:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giannouli AL, Kintzios SE. Essential oils of Salvia spp: Examples of intra-specific and seasonal variation. In: Kintzios SE, editor. Sage: The Genus Salvia. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croteau R, El-Bialy H, Dehal SS. Metabolism of monoterpenes: Metabolic fate of (+)-camphor in sage (Salvia officinalis) Plant Physiol. 1987;84:643–8. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senatore F, Arnold NA, Piozzi F, Formisano C. Chemical composition of the essential oil of Salvia microstegia Boiss. et Balansa growing wild in Lebanon. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1108:276–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Özek G, Özek T, Işcan G, Başer KH, Hamzaoglu E, Duran A. Comparison of hydrodistillation and microdistillation methods for the analysis of fruit volatiles of Prangos pabularia Lindl., and evaluation of its antimicrobial activity. S Afr J Bot. 2007;73:563–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang Q, Liang Z, Wang J, Xu W. Essential oil composition of Salvia miltiorrhiza flower. Food Chem. 2009;113:592–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon JE, Bubenheim DR, Joly RJ, Charles DJ. Water stress induced alterations in essential oil content and composition of sweet basil. J Essent Oil Res. 1992;4:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neffati M, Marzouk B. Changes in essential oil and fatty acid composition in coriander (Coriandrum sativum l.) leaves under saline conditions. Ind Crop Prod. 2008;28:137–42. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendawy SF, Khalid KA. Response of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) plants to zinc application under different salinity levels. J Appl Sci Res. 2005;1:147–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khalid KH. Influence of water stress on growth, essential oil, and chemical composition of herbs (Ocimum Sp.) Int Agrophysics. 2006;20:289–96. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burbott AJ, Loomis WD. Evidence for metabolic turnover of monoterpenes in peppermint. Plant Physiol. 1969;44:173–9. doi: 10.1104/pp.44.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munné-Bosch S, Alegre L. Drought-induced changes in the redox state of a-tocopherol, ascorbate and the diterpene carnosic acid in chloroplasts of Labiatae species differing in carnosic acid contents. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:1816–25. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.019265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putievsky E, Ravid U, Sanderovich D. Morphological observations and essential oils of sage (Salvia officinalis L.) under cultivation. J Essent Oil Res. 1992;4:291–3. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hidalgo P, Ubera J, Tena M, Valcárcel M. Determination of carnosic acid in wild and cultivated Rosmarinus officinalis. J Agri Food Chem. 1998;46:2624–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munné-Bosch S, Alegre L, Schwarz K. The formation of phenolic diterpenes in Rosmarinus officinalis L under Mediterranean climate. Eur Food Res Technol. 2000;210:263–7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byun-McKay A, Godard KA, Toudefallah M, Martin DM, Alfaro R, King J, et al. Wound-induced terpene synthase gene expression in Sitka spruce that exhibit resistance or susceptibility to attack by the white pine weevil. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:1009–21. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.071803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kutuk C, Cayci G, Heng LK. Effects of increasing salinity and N-15 labelled urea levels on growth, N uptake, and water use efficiency of young tomato plants. Aust J Soil Res. 2004;42:345–51. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boelens MH. Essential oils and aroma chemicals from Eucalyptus globulus Labill. Perfum Flavor1985. 9:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Areias F, Valentão P, Andrade PB, Ferreres F, Seabra RM. Flavonoids and phenolic acids of sage: Influence of some agricultural factors. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:6081–4. doi: 10.1021/jf000440+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]