Abstract

Context

Family planning services are essential for reducing high rates of unintended pregnancies among young people, yet a perception that providers will not preserve confidentiality may deter youth from accessing these services. This systematic review, conducted in 2011, summarizes the evidence on the effect of assuring confidentiality in family planning services to young people on reproductive health outcomes. The review was used to inform national recommendations on providing quality family planning services.

Evidence acquisition

Multiple databases were searched to identify articles addressing confidentiality in family planning services to youth aged 10–24 years. Included studies were published from January 1985 through February 2011. Studies conducted outside the U.S., Canada, Europe, Australia, or New Zealand, and those that focused exclusively on HIV or sexually transmitted diseases, were excluded.

Evidence synthesis

The search strategy identified 19,332 articles, nine of which met the inclusion criteria. Four studies examined outcomes. Examined outcomes included use of clinical services and intention to use services. Of the four outcome studies, three found a positive association between assurance of confidentiality and at least one outcome of interest. Five studies provided information on youth perspectives and underscored the idea that young people greatly value confidentiality when receiving family planning services.

Conclusions

This review demonstrates that there is limited research examining whether confidentiality in family planning services to young people affects reproductive health outcomes. A robust research agenda is needed, given the importance young people place on confidentiality.

Context

The high rates of unintended pregnancy among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. make family planning services essential.1 Many factors, however, can inhibit young people from accessing these services, including a perception that services will not be kept confidential. Without the assurance of confidentiality, defined by the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM) as “an agreement between adolescent and provider that information discussed during or after the encounter will not be shared with other parties without the explicit permission of the patient,”2 young people may resist seeking needed healthcare services.3–7 Furthermore, once in a clinic setting, adolescents with concerns about confidentiality may be reticent to discuss more-sensitive healthcare issues, such as sexual activity and family planning.2,5,8 SAHM and the American Academy of Pediatrics have affirmed the importance of confidentiality in adolescent healthcare settings.2,4,9 As discussed in a complementary systematic review on youth-friendly family planning services in this series, assurance of confidentiality was the characteristic most frequently cited by young people and providers as important in youth-friendly family planning services.10

In clinic settings, a number of conditions may threaten assurances of confidentiality for young people in the context of general healthcare services, including family planning. Some providers simply do not provide healthcare services to young people confidentially, some do not explicitly discuss confidentiality with young people, and some lack training on the provision of confidential healthcare services to adolescents and young adults.11,12 Young people who have health insurance through their parents’ plans may have their confidentiality breached when an explanation of benefits that identifies services received is sent home and opened by a parent.13,14 The issue is further complicated by the legal and ethical limits of confidentiality, such as in the case of legal obligations to report child abuse and when the patient has suicidal ideation or indicates potential harm to others. Additionally, laws governing adolescents’ rights to consent to healthcare services, which are inextricably linked to confidentiality, vary by state and specific circumstances such as when the adolescent is married versus single, and type of services needed (e.g., sexually transmitted disease [STD] testing or treatment, or provision of contraceptives).4,12 Given these issues, further investigation of the effect of assurance of confidentiality in the provision of family planning services on specific reproductive health outcomes is warranted.3,4

Conducted in 2011, the purpose of this systematic review was to summarize the evidence of the effect of assuring confidentiality in family planning services to young people on reproductive health outcomes. A secondary aim was to summarize youth perspectives on confidentiality. Barriers and facilitators that providers face in assuring confidentiality were also examined.

The Office of Population Affairs (OPA) and CDC used the evidence presented here, along with findings from a series of systematic reviews,15 to inform the development of “Providing Quality Family Planning Services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs.”16

Evidence Acquisition

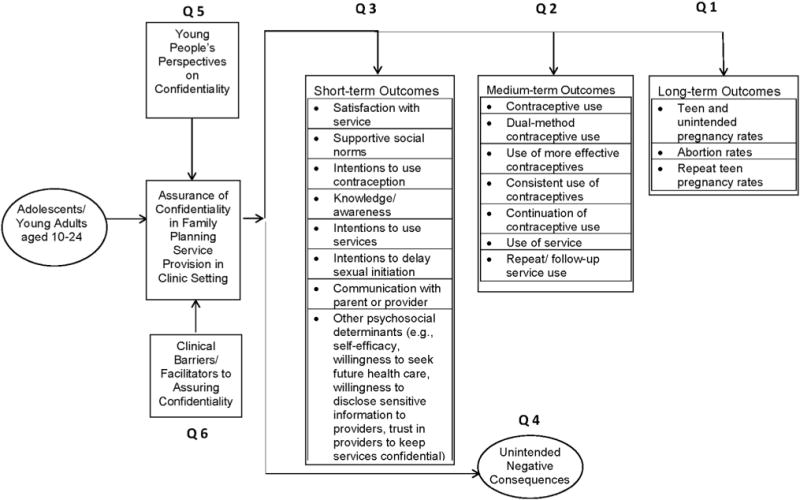

The methods for conducting this systematic review have been described elsewhere.17 Six key questions (Table 1) were developed. An analytic framework (Figure 1) was then applied to show the logical relationships among the population of interest (adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years); the intervention of interest (assurance of confidentiality in family planning service provision in a clinical setting); and long-, medium-, and short-term outcomes of interest. The first three key questions examined the effects of assurance of confidentiality in the provision of family planning services to young people on long-, medium-, or short-term reproductive health outcomes of interest. Long-term outcomes included reduced teen or unintended pregnancy rates. Medium-term outcomes included facets of contraceptive use (e.g., use of more-effective contraceptives or more consistent use of contraceptives) and use of services. Short-term outcomes included psychosocial factors (e.g., willingness to seek future health care, willingness to disclose sensitive information to providers, trust in providers to keep services confidential), as well as communication with providers or parents about reproductive health issues. All summary measures reporting relevant outcomes were considered for review. The fourth key question examined whether any unintended negative consequences were associated with the assurance of confidentiality in the provision of family planning services (e.g., increased sexual activity being associated with receiving confidentiality assurances). The fifth key question examined youth perspectives on confidentiality in family planning services, and the sixth key question examined barriers and facilitators for clinics in assuring confidential services. Search strategies (Appendix A) were then developed and used to identify relevant articles in several electronic databases (Appendix B).

Table 1.

Key Questions

| Key question no. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | Is there a relationship between assurance of confidentiality in the provision of family planning services to young people and improved long-term outcomes (i.e., decreased teen or unintended pregnancy rates, decreased abortion rates, decreased repeat teen pregnancy rates)? |

| 2 | Is there a relationship between assurance of confidentiality in the provision of family planning services to young people and improved medium-term outcomes (i.e., increased contraceptive use, increased use of more effective contraceptives, increased consistent use of contraceptives, increased continuation of contraceptive use, increased use of services)? |

| 3 | Is there a relationship between assurance of confidentiality in the provision of family planning services to young people and improved short-term outcomes (i.e., psychosocial outcomes [such as self-efficacy, willingness to seek future health care, willingness to disclose sensitive information to providers, trust in providers to keep services confidential], and communication with parents or providers about reproductive health)? |

| 4 | Are there unintended negative consequences associated with assuring confidentiality when providing young people family planning services? |

| 5 | What are young people’s perspectives on confidentiality in the provision of family planning services? |

| 6 | What are the barriers and facilitators for clinics in assuring confidentiality in family planning services to young people? |

Figure 1.

Analytic framework.

Selection of Studies

Retrieval and inclusion criteria for all reviews in this series have been described elsewhere.17 Specific to this review, articles must have been full length and published in peer-reviewed journals in English from January 1, 1985, through February 28, 2011, and must have reported data specific to individuals aged 10–24 years. Articles that focused on policy interventions (e.g., a state law requiring parental notification for certain services) were excluded because they were considered to be outside the purview of the clinic setting.

Some inclusion criteria were specific to key questions. For Key Questions 1–4, which sought to examine the effect of assurance of confidentiality on outcomes and identify any unintended negative consequences, studies had to include a comparison group or pre–post measures if there was only a single study group. Given the descriptive nature of Key Questions 5 and 6, which sought to examine youth perspectives on confidentiality and clinical barriers or facilitators, non-comparative studies (i.e., studies that did not include a comparison group or pre–post measures) were included to capture most potentially relevant literature.

Assessment of Study Quality and Synthesis of Data

The methodology used for synthesizing the data and assessing quality of individual studies is described in detail elsewhere.17 Briefly, each analytic study was assessed to evaluate the risk that the findings may be confounded by a systematic bias, using a schema developed by U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).18 A rating of risk for bias was determined by assessing the presence or absence of several characteristics known to protect a study from the confounding influence of bias. Criteria for this process were developed based on recommendations from several sources, including the USPSTF18; the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system19; and the Community Guide for Preventive Services.20 Study quality was not assessed for the non-analytic studies, as they did not measure associations and had no comparison group.

Evidence Synthesis

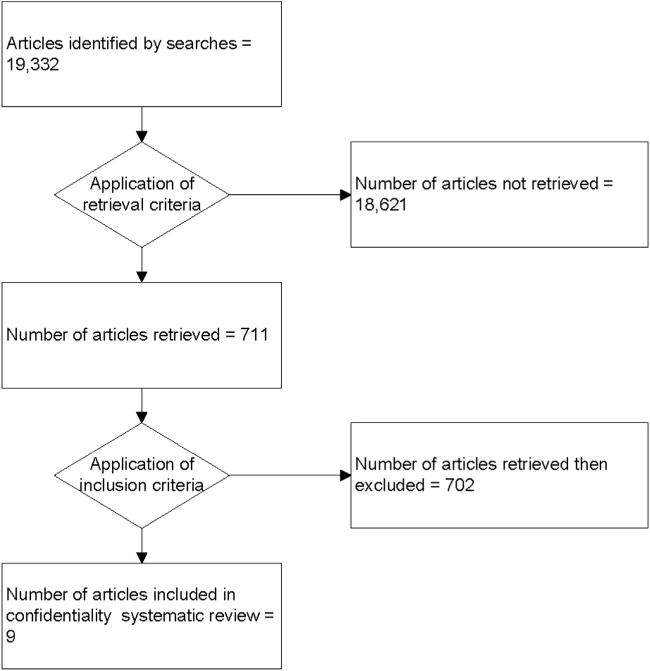

The search strategy yielded 19,332 articles (Figure 2). After an initial title and abstract content screen, 711 articles were retrieved for full review. The other 18,621 citations were not retrieved because they were either not relevant to the key questions or did not report on original studies. After applying the inclusion criteria to the 711 retrieved articles, nine articles were included in the final review.5,8,11,21–26 Two22,26 were conducted in the United Kingdom, and the remaining5,8,11,21,23–25 in the U.S. None of the nine studies addressed long-term outcomes. One study8 examined medium- and short-term outcomes, as well as provided youth perspectives on confidentiality. One study21 examined a short-term outcome and also provided youth perspectives. Two studies5,24 examined only short-term outcomes. Five studies11,22,23,25,26 did not examine outcomes but did provide descriptive information. Two of these22,23 addressed youth perspectives on confidentiality. Two articles11,23 addressed clinical facilitators or barriers. One22 addressed both youth perspectives on confidentiality and clinical facilitators/barriers. No studies examined unintended negative consequences.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram showing evolution of evidence bases.

Studies Examining the Effect of Confidentiality on Reproductive Health Outcomes

A range of study designs was used in the four studies8,12,21,24 that examined the effect of assuring confidentiality on reproductive health outcomes, and the risk for bias in these studies varied. One RCT5 was rated as having low risk for bias, one pre–post study21 was rated as having moderate risk for bias, and two cross-sectional studies were rated as having high24 or moderate8 risk for bias. Sample sizes ranged from 5321 to 1,715.8 Three studies5,8,21 recruited young people from schools and one study24 recruited youth from clinics. The age of study populations ranged from 12 to 21 years. Appendix D provides more detailed information on each study.

One study8 examined the provision of pelvic examinations, a medium-term outcome. This cross-sectional study examined the relationship between adolescent perceptions of confidentiality of care provided by their regular healthcare provider and use of this provider for pelvic examinations. A higher proportion of teens who believed their provider would deliver confidential care reported having obtained health care without parental knowledge within the last year than those who did not believe their provider would keep their care confidential (13% vs 6%, p < 0.001). The odds of having a pelvic examination in the previous 2 years was higher among female teens who perceived that their provider offered confidential care as compared with those who did not (OR=3.3, 95% CI=2.1, 5.5). Among all teens in the study, regardless of perceptions of confidential care, 8% reported having forgone health care in the last year because of fear that parents would find out; however, no differences were found when comparing teens who did and did not perceive confidential care.

Various short-term outcomes were examined. One study5 investigated the influence of physician assurance of confidentiality on adolescent willingness to seek future health care for routine health needs. This study also assessed a related psychosocial outcome: adolescent willingness to disclose sensitive information (i.e., information about sexuality, substance use, and mental health) to the provider after hearing a confidentiality assurance statement. One study8 explored the association between trust in providers to keep services confidential and young people’s communication with those providers. One study21 explored changes in adolescent beliefs in a provider to keep certain services confidential after hearing a confidentiality assurance statement that explained what can be kept confidential and what cannot. Association between communication with parents about a clinic visit and receipt of confidential services at that visit was examined in another study.24

One RCT5 examined the influence of physician confidentiality assurance statements on willingness to seek future health care and found a significant effect. In this study, 562 adolescents were randomly assigned to one of three study groups. Adolescents listened to a standardized audiotape depiction of an office visit during which they heard either (1) a physician who assured unconditional confidentiality (all discussions and services are kept confidential); (2) a physician who assured conditional confidentiality (discussions and services are confidential except in cases of suspected abuse or self-harm); or (3) a physician who did not mention confidentiality (control group). Adolescents assured of confidentiality (the conditional and unconditional groups combined) more frequently reported willingness to return to see that physician in the future compared with those who were not assured of confidentiality (67% vs 53%, p < 0.001). Adolescents assured of unconditional confidentiality by a physician more frequently reported willingness to return for a future visit to see that physician compared with those who were assured conditional confidentiality (72% vs 62%, p=0.001).

That study5 also found a positive effect between assurance of confidentiality from a provider and a young person’s willingness to disclose sensitive information to that provider. Adolescents assured of confidentiality (the conditional and unconditional groups combined) by a provider more frequently reported willingness to disclose sensitive information regarding sexuality, substance use, and mental health to that provider compared with those who were not assured of confidentiality (46.5% vs 39%, p=0.02).

One cross-sectional study8 found a positive association between the perception of confidentiality among young people and communication with providers about sensitive topics. In this study, the adjusted odds of having discussed sex-related topics with a provider in the past year was higher among youth who perceived that their provider would maintain confidentiality compared with those who did not (OR=2.7, 95% CI=2.2, 3.4).

One pre–post study21 assessed changes in adolescent beliefs in a provider to keep certain services confidential after hearing a confidentiality assurance statement that explained what can be kept confidential and what cannot. After hearing the statement, the percentage of students who believed a doctor would keep services confidential increased for the following services: receiving birth control injections (49% to 72%); being tested for HIV (45% to 70%); being tested for STDs (45% to 76%); diagnosing an STD (6% to 28%); and treating an STD (11% to 36%). However, in this study, no tests of statistical significance were conducted.

A cross-sectional study24 examined the hypothesis that receipt of confidential services may undermine a young person’s communication with parents about those services. The study compared two groups of young people: those receiving services that could be obtained confidentially and without parental notification under the current applicable state law (e.g., obtaining birth control; n=29), and those for whom parental consent for treatment was needed (e.g., upper respiratory illness; n=30). The authors examined responses to three parental communication measures and found no statistically significant differences between the group that received confidential services and the group that received non-confidential services: 54% versus 46%, respectively, told parent(s) they were coming to clinic; 46% versus 54%, respectively, told parent(s) all the reasons they were coming to clinic; and 48% versus 52%, respectively, would tell parent(s) if they had a serious or sensitive health problem.

Studies Describing Perspectives of Young People on Confidentiality

Five studies8,21,22,25,26 examined youth perspectives on confidentiality. More detailed information on these five studies is presented in Appendix C. In a cross-sectional study8 that examined perceptions of confidentiality of care among public high school students in Grades 9 and 12, 75% of all teens reported that they would like to be able to obtain health care without parents knowing about it for some or all health concerns. In another study,22 which used an in-school survey and focus groups with young people living in rural settings, participants emphasized that confidentiality is a concern during several stages of receiving sexual healthcare services, including the waiting room, when seeing the doctor, and at the pharmacy. In the third study,26 which explored the importance of confidentiality in sexual health services among ninth-grade students living in urban and rural areas of the United Kingdom, 56% of youth rated confidentiality as the most important feature of sexual health services, 86% reported they were more likely to use a service if it was kept confidential, and 55% reported they would not use a service if it was not confidential.

Using private semi-structured interviews, a fourth study21 elicited suggestions from public school students in Grades 9 and 12 about how to better convey the protections and limitations of confidentiality. Participants suggested the following: emphasizing the protections of confidentiality during conditional confidentiality assurances, selecting words carefully, and behaving in ways that convey trustworthiness. More broadly, the young people offered that it would be helpful if information about confidential adolescent health care were conveyed through media, schools, and peer opinion leaders to support provider interactions.

Lastly, the fifth study25 examined adolescent receptive-ness when offered confidential billing accounts in which enrollees agree to pay when and what they can by themselves, thereby preserving confidentiality by preventing submission of itemized bills to parents. Of those offered the service, 95% enrolled.

Studies Describing Barriers and Facilitators Facing Clinics in Assuring Confidentiality

Three studies10,19,20 described clinical perspectives on barriers and facilitators clinics face in assuring confidentiality in the provision of family planning services to young people. More detailed information on these articles is presented in Appendix C. One study11 identified a number of barriers: limited time to spend with adolescents during office visits, lack of training in adolescent health and medicine, difficulties keeping billing and medical records confidential, and the sensitivity surrounding confidential health care for adolescents. The study also noted conditions that served as facilitators: having an office policy on adolescent confidentiality and the ability of staff and providers to communicate correctly and consistently on office confidentiality policies. Taking time during consultations to address young people’s specific concerns about the nature of confidentiality was also described as helpful. Another study22 found factors that could help facilitate the assurance of confidentiality: securing private time with patients when parents are present and awareness of adolescents’ fears of losing anonymity. Providing services in locations that secured anonymity also were beneficial. In the third study,23 certain beliefs among providers were described as facilitators: the belief that adolescents may not seek contraceptive services if their parents are notified, and the belief that contraceptive access may improve public health.

Discussion

This review demonstrates that there is limited research examining whether the assurance of confidentiality in family planning services to young people affects reproductive health outcomes and underscores the need for more rigorous research. No studies addressed long-term outcomes. One study8 examined a behavioral outcome—use of services. This study found that a perception of confidentiality was positively associated with using a provider for pelvic examinations.

The review provided limited evidence of confidentiality’s effect on a few proximal outcomes. Of the four studies examining associations with short-term outcomes, three found a positive association; confidentiality assurances were associated with willingness to seek future health care for routine health needs and to disclose sensitive information (including information related to sexual health),5 increased frequency of reporting having talked with a provider about sex-related topics in the past,8 and trust in the provider to keep services related to sexual health issues confidential.21 The fourth study24 examined whether the receipt of confidential family planning services undermines communication between a young person and his/her parents about the clinic visit and found that receipt of confidential services did not affect this type of communication with parents.

The systematic review also identified five studies8,21,22,25,26 (including two of the outcome studies8,21) that provided young people’s perspectives on confidentiality. Three of these studies reaffirmed the position that multiple medical associations have recognized: young people greatly value confidentiality when receiving reproductive health and family planning services. These perspectives underscore the importance young people place on confidentiality and lend support to the argument that preserving confidentiality in the provision of family planning services may improve young people’s receptiveness to seeking and receiving those services.

Limitations

The analytic studies that examined reproductive health outcomes have several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the evidence. Of these four studies, only one addressed a medium-term outcome, and none addressed long-term outcomes. Only one5 of the four studies was rated as having a low risk for bias, two8,21 were rated as having a moderate risk for bias, and one24 was rated as having a high risk for bias. Types of potential bias in the studies included selection bias,24 recall bias,8,24,27 self-report bias,5,8,21,24,27 and causal relationship bias.8,24,27 Small sample size, limiting the generalizability of the studies’ findings, was an issue in two studies.21,24 Participation rates were not assessed in one study24 and potential non-response bias was not examined in another study.21 Also, the RCT used a school-based sample, rather than a clinic-based sample, to permit inclusion of adolescents who might not present to a clinic setting because of confidentiality concerns. Thus, participants were responding to simulated clinic scenarios in the school setting, and their willingness to disclose sensitive information and to return for visits in real-life clinic situations is unknown. In the study that examined whether the receipt of confidential reproductive health services undermined youth’s communication with parents about those services, the authors did not assess whether the participants actually knew whether the services they were receiving were those that could be provided confidentially or not. If the youth did not know the confidentiality status of the services they were seeking, the study’s findings on the association between confidential services and communication with parents may be inaccurate. A limitation across studies was the lack of focus on college students, a potentially important population of young adults, as they are living on their own and yet still potentially under their parents’ health plans.

Recommendations

Owing to the limited number of outcome studies meeting the inclusion criteria, the diversity of examined outcomes, and the limitations noted previously, definitive conclusions about the effect of confidentiality assurances on young people’s reproductive health outcomes cannot be drawn. The review did provide limited evidence of confidentiality’s effect on a few proximal outcomes, such as intention to use services or willingness to discuss sensitive issues with a provider. According to the analytic framework, these more proximal outcomes would be the first outcomes to be influenced, but may support the idea of potential longer-term effects. The descriptive information in this review highlights the importance young people place on confidential reproductive health services, supporting what other articles and medical associations have also recognized.1,4,7,9,28–30 The evidence base would be greatly strengthened with the addition of robust studies examining longer-term outcomes such as contraceptive use.

The review also points to barriers and facilitators that clinics face, as identified from studies examining viewpoints of a range of staff and healthcare providers.11,22,23 Rigorous evaluation of these factors to determine whether they influence the perception of confidentiality among young people, and assessing any subsequent impact on outcomes, would build the literature base and could provide much needed evidence on how to improve reproductive health services for young people.

Further investigation of ways to enhance understanding among young people and providers about the legal protections and limits of confidential family planning services is needed. In the RCT5 that examined the effect of confidentiality assurances on the outcomes of interest, assurances increased the percentage of youth willing to seek future health care but also showed that adolescents may not be able to understand the differences between health concerns routinely addressed confidentially and issues that cannot be kept confidential, such as abuse or self-harm. Another study21 showed that hearing a confidentiality assurance statement from a provider increased the proportion of adolescents who believed a doctor would keep certain services confidential, but also showed that these statements were only partially effective in increasing young people’s understanding of the protections of confidentiality related to sexual health issues.

Future investigations should consider research that tests how to best educate young people and providers about state-specific laws related to adolescents and confidential healthcare services, as well as how best to train providers in communicating with young people so as to increase their understanding of confidentiality in the context of family planning services. General messages about the availability of confidential health care for young people through media (e.g., messages on TV, in teen magazines); schools; and other venues for adolescents may also be beneficial.

Only two of the included studies addressed the challenges related to explanation of benefits sent home by health insurance providers and their potential to infringe on adolescent confidentiality. One study11 noted explanations of benefits among the critical barriers to assuring confidentiality in clinical settings, and the other25 explored alternative billing options with adolescents to curtail this issue. This is an ongoing issue that needs further research attention.

Conclusions

There is limited research demonstrating that the assurance of confidentiality to young people in the provision of family planning services affects reproductive health outcomes. Only four outcome studies showed a positive association between assurances of confidentiality and the outcomes of interest; all but one of these lacked rigorous study designs and had a moderate or high risk of bias. Additional non-comparative studies reaffirmed the idea that young people greatly value confidentiality in the context of family planning services and suggested factors that may assist or hinder clinics in their efforts to assure confidentiality when providing family planning services to young people. A research agenda calling for rigorous studies examining longer-term outcomes such as contraceptive use should be a top priority.

Along with evidence from the other systematic reviews in this series, findings from this systematic review were presented to an expert panel in May 2011 at a meeting convened by the OPA and CDC. Combined with expert feedback, these reviews were used to inform the development of the 2014 “Providing Quality Family Planning Services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs.”16 It is possible that additional articles meeting the inclusion criteria for this systematic review have been published since our systematic search of the literature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Publication of this article was supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of Population Affairs (OPA).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for their helpful review of this manuscript: Loretta Gavin, MPH, PhD, and Alison Spitz RN, MPH. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.001.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Brindis CD, Morreale MC, English A. The unique health care needs of adolescents. Future Child. 2003;13(1):117–135. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1602643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sigman G, Silber TJ, English A, Epner JE. Confidential health care for adolescents: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1997;21(6):408–415. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00171-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(9700171-7). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng TL, Savageau JA, Sattler AL, DeWitt TG. Confidentiality in health care: a survey of knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes among high school students. JAMA. 1993;269(11):1404–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.269.11.1404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1993.03500110072038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford CA, English A, Sigman G. Confidential health care for adolescents: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(2):160–167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(04)00086-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford CA, Millstein SG, Halpern-Felsher BL, Irwin Influence of physician confidentiality assurances on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information and seek future health care. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(12):1029–1034. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03550120089044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oberg C, Hogan M, Bertrand J, Juve C. Health care access, sexually transmitted diseases, and adolescents: Identifying barriers and creating solutions. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32(9):320–339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mps.2002.128719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy DM, Fleming R, Swain C. Effect of mandatory parental notification on adolescent girls’ use of sexual health care services. JAMA. 2002;288(6):710–714. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.710. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.6.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thrall JS, McCloskey L, Ettner SL, Rothman E, Tighe JE, Emans SJ. Confidentiality and adolescents’ use of providers for health information and for pelvic examinations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(9):885–892. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.9.885. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.154.9.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein J. Achieving quality health services for adolescents: policy statement of the Committee on Adolescence. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):1263–1270. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0694. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brittain AW, Williams JR, Zapata LB, et al. Youth-friendly family planning services for young people: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S73–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akinbami LJ, Gandhi H, Cheng TL. Availability of adolescent health services and confidentiality in primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):394–401. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford CA, Millstein SG. Delivery of confidentiality assurances to adolescents by primary care physicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(5):505–509. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170420075013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170420075013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold R. Unintended Consequences: how insurance processes inadvertently abrogate patient confidentiality. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2009;12(4):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slive L, Cramer R. Health reform and the preservation of confidential health care for young adults. J Law Med Ethics. 2012;40(2):383–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gavin LE, Moskosky SB, Barfield WD. Introduction to the supplement: development of federal recommendations for family planning services. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S1–S5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gavin L, Moskosky MS, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-04):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tregear SJ, Gavin LE, Williams JR. Systematic review evidence methodology: providing quality family planning services. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2S1):S23–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. US Preventive Services Task Force Procedure Manual. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, USDHHS; 2008. pp. 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7652):1049–1051. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39493.646875.AE. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39493.646875.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based Guide to Community Preventive Services—methods. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 suppl):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00119-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford CA, Thomsen SL, Compton B. Adolescents’ interpretations of conditional confidentiality assurances. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(3):156–159. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00251-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garside R, Ayres R, Owen M, Pearson VA, Roizen J. Anonymity and confidentiality: rural teenagers’ concerns when accessing sexual health services. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;28(1):23–26. doi: 10.1783/147118902101195965. http://dx.doi.org/10.1783/147118902101195965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Adolescents, contraception and confidentiality: a national survey of obstetrician-gynecologists. Contraception. 2011;84(3):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.12.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerand SJ, Ireland M, Boutelle K. Communication with our teens: associations between confidential service and parent-teen communication. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20(3):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2007.01.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rainey DY, Brandon DP, Krowchuk DP. Confidential billing accounts for adolescents in private practice. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26(6):389–391. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00079-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas N, Murray E, Rogstad KE. Confidentiality is essential if young people are to access sexual health services. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(8):525–529. doi: 10.1258/095646206778145686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/095646206778145686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuster MA, Bell RM, Petersen LP, Kanouse DE. Communication between adolescents and physicians about sexual behavior and risk prevention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(9):906–913. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170340020004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170340020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emans SJ, Brown RT, Davis A, Felice M, Hein K. Society for Adolescent Medicine position paper on reproductive health care for adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(8):649–661. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90014-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein JD, Slap GB, Elster AB, Schonberg SK. Access to health care for adolescents: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90084-o. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(92)90084-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein JD, Wilson KM, McNulty M, Kapphahn C, Collins KS. Access to medical care for adolescents: results from the 1997 Commonwealth Fund Survey of the Health of Adolescent Girls. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25:120–130. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00146-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.