Summary

Traditional voxel-level multiple testing procedures in neuroimaging, mostly p-value based, often ignore the spatial correlations among neighboring voxels and thus suffer from substantial loss of power. We extend the local-significance-index based procedure originally developed for the hidden Markov chain models, which aims to minimize the false nondiscovery rate subject to a constraint on the false discovery rate, to three-dimensional neuroimaging data using a hidden Markov random field model. A generalized expectation-maximization algorithm for maximizing the penalized likelihood is proposed for estimating the model parameters. Extensive simulations show that the proposed approach is more powerful than conventional false discovery rate procedures. We apply the method to the comparison between mild cognitive impairment, a disease status with increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s or another dementia, and normal controls in the FDG-PET imaging study of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, False discovery rate, Generalized expectation-maximization algorithm, Ising model, Local significance index, Penalized likelihood

1. Introduction

In a seminal paper, Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) introduced false discovery rate (FDR) as an alternative measure of Type I error in multiple testing problems to the family-wise error rate (FWER). They showed that the FDR is equivalent to the FWER if all null hypotheses are true and is smaller otherwise, thus FDR controlling procedures potentially have a gain in power over FWER controlling procedures. FDR is defined as the expected proportion of false rejections among all rejections. The false nondiscovery rate (FNR; Genovese and Wasserman, 2002), the expected proportion of falsely accepted hypotheses, is the corresponding measure of Type II error. The traditional FDR procedures (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995, 2000; Genovese and Wasserman, 2004), which are p-value based, are theoretically developed under the assumption that the test statistics are independent. Although these approaches are shown to be valid in controlling FDR under certain dependence assumptions (Benjamini and Yekutieli, 2001; Farcomeni, 2007; Wu, 2008), they may suffer from severe loss of power when the dependence structure is ignored (Sun and Cai, 2009). By modeling the dependence structure using a hidden Markov chain (HMC), Sun and Cai (2009) proposed an oracle FDR procedure built on a new test statistic, the local index of significance (LIS), and the corresponding asymptotic data-driven procedure, which are optimal in the sense that they minimize the marginal FNR subject to a constraint on the marginal FDR. Following the work of Sun and Cai (2009), Wei et al. (2009) developed a pooled LIS (PLIS) procedure for multiple-group analysis where different groups have different HMC dependence structures, and proved the optimality of the PLIS procedure. Either the LIS procedure or the PLIS procedure only handles the one-dimensional dependency. However, problems with higher dimensional dependence are of particular practical interest in analyzing imaging data.

FDR procedures have been widely used in analyzing neuroimaging data, such as positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data (Genovese, Lazar, and Nichols, 2002; Chumbley and Friston, 2009; Chumbley et al., 2010, among many others). We extend the work of Sun and Cai (2009) in this article by developing an optimal LIS-based FDR procedure for three-dimensional (3D) imaging data using a hidden Markov random field model (HMRF) for the spatial dependency among multiple tests. Existing methods for correlated imaging data, for example, Zhang, Fan, and Yu (2011) are not shown to be optimal, i.e., minimizing FNR.

HMRF model is a generalization of HMC model, which replaces the underlying Markov chain by Markov random field. A well-known classical Markov random field with two states is the Ising model. In particular, the two-parameter Ising model, whose formal definition is given in Equation (1), reduces to the two-state Markov chain in one-dimension (Bremaud, 1999). The Ising model and its generalization with more than two states, the Potts model, have been widely used to capture the spatial structure in image analysis; see Bremaud (1999), Winkler (2003), Zhang et al. (2008), Huang et al. (2013) and Johnson et al. (2013), among others. In this article, we consider a hidden Ising model for each area based on the Brodmann’s partition of the cerebral cortex (Garey, 2006) and subcortical regions of the human brain, which provides a natural way of modeling spatial correlations for neuroimaging data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work that introduces the HMRF-LIS based FDR procedure to the field of neuroimaging.

We propose a generalized expectation-maximization algorithm (GEM; Dempster et al., 1977) to search for penalized maximum likelihood estimators (Ridolfi, 1997; Ciuperca, Ridolfi, and Idier, 2003; Chen, Tan, and Zhang, 2008) of the hidden Ising model parameters. The penalized likelihood prevents the unboundedness of the likelihood function, and the proposed GEM uses Monte Carlo averages via Gibbs sampler (Geman and Geman, 1984; Roberts and Smith, 1994) to overcome the intractability of computing the normalizing constant in the underlying Ising model. Then the LIS-based FDR procedures can be conducted by plugging in the estimates of the hidden Ising model parameters. In what follows, we use the term “HMRF” to refer to the 3D hidden Ising model.

The article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the HMRF model, i.e., the hidden Ising model, for 3D imaging data. We provide the GEM algorithm for the HMRF parameter estimation and the implementation of the HMRF-LIS-based data-driven procedures in Section 3. In Section 4, we conduct extensive simulations to compare the LIS-based procedures with conventional FDR methods. In Section 5, we apply the PLIS procedure to the 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET) image data of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), which finds more signals than conventional methods.

2. A Hidden Markov Random Field Model

Let S be a finite lattice of N voxels in an image grid, usually in a 3D space. Let Θ = {Θs ∈ {0, 1}: s ∈ S} denote the set of latent states on S, where Θs = 1 if the null hypothesis at voxel s is false and Θs = 0 otherwise. For simplicity, we follow Sun and Cai (2009) to call hypothesis s to be nonnull if Θs = 1 and null otherwise. We also call voxel s to be a signal if Θs = 1 and noise otherwise. Let Θ be generated from a two-parameter Ising model with the following probability distribution

| (1) |

where Z(φ) is the normalizing constant, φ = (β, h)T, H(θ) = (Σ〈s,t〉 θsθt, Σs∈S θs)T, and 〈s, t〉 denotes all the unordered pairs in S such that for any s, t is among the six nearest neighbors of voxel s in a 3D setting. This model possesses the Markov property:

where S \{s} denotes the set S after removing s, and

(s) ⊂ S is the nearest neighborhood of s in S. Some parameter interpretations of β and h are given in Web Appendix A.

(s) ⊂ S is the nearest neighborhood of s in S. Some parameter interpretations of β and h are given in Web Appendix A.

We assume the observed z-values X = {Xs: s ∈ S} are independent given Θ= θ with

| (2) |

where Pϕ(xs|θs) denotes the following distribution

| (3) |

with , unknown parameters and pl ≥ 0. In particular, the z-value Xs follows the standard normal distribution under the null, and the nonnull distribution is set to be the normal mixture that can be used to approximate a large collection of distributions (Magder and Zeger, 1996; Efron, 2004). The number of components L in the nonnull distribution may be selected by, for example, the Akaike or Bayesian information criterion. Following the recommendation of Sun and Cai (2009), we use L = 2 for the ADNI image analysis.

Markov random fields (MRFs; Bremaud, 1999) are a natural generalization of Markov chains (MCs), where the time index of MC is replaced by the space index of MRF. It is well known that any one-dimensional MC is an MRF, and any one-dimensional stationary finite-valued MRF is an MC (Chandgotia et al., 2014). When S is taken to be one-dimensional, the above approach based on (1)–(3) reduces to the HMC method of Sun and Cai (2009).

3. Hidden Markov Random Field LIS-Based FDR Procedures

Sun and Cai (2009) developed a compound decision theoretic framework for multiple testing under HMC dependence and proposed LIS-based oracle and data-driven testing procedures that aim to minimize the FNR subject to a constraint on FDR. We extend these procedures under HMRF for image data. The oracle LIS for hypothesis s is defined as LISs(x) = PΦ(Θs = 0|x) for a given parameter vector Φ. In our model, Φ = (ϕT, φT)T. Let LIS(1)(x), …, LIS(N)(x) be the ordered LIS values and

, …,

, …,

the corresponding null hypotheses. The oracle procedure operates as follows: for a prespecified FDR level α,

the corresponding null hypotheses. The oracle procedure operates as follows: for a prespecified FDR level α,

| (4) |

Parameter Φ is unknown in practice. We can use the data-driven procedure that simply replaces LIS(i)(x) in (4) with , where Φ̂ is an estimate of Φ.

If all the tests are partitioned into multiple groups and each group follows its own HMRF, in contrast to the separated LIS (SLIS) procedure that conducts the LIS-based FDR procedure separately for each group at the same FDR level α and then combines the testing results, we follow Wei et al. (2009) to propose a pooled LIS (PLIS) procedure that is more efficient in reducing the global FNR. The PLIS follows the same procedure as (4), but with LIS(1), …, LIS(N) being the ordered test statistics from all groups.

Note that the model homogeneity, which is required in Sun and Cai (2009) and Wei et al. (2009) for HMCs, fails to hold for the HMRF model. In other words, P(Θs = 1) for the interior voxels with six nearest neighbors are different to those for the boundary voxels with less than six nearest neighbors. We show the validity and optimality of the oracle HMRF-LIS-based procedures in Web Appendix B.

We now provide details of the LIS-based data-driven procedure for 3D image data, where the parameters of the HMRF model need to be estimated from observed test data.

3.1 A Generalized EM Algorithm

The observed likelihood function under HMRF, L(Φ|x) = PΦ(x) = ΣΘPϕ(x|Θ)Pφ(Θ), is unbounded (see Web Appendix C for details). One solution to avoid the unboundedness is to replace the likelihood by a penalized likelihood (Ridolfi, 1997; Ciuperca et al., 2003)

| (5) |

where , l = 1, …, L, are penalty functions that ensure the boundedness of pL(Φ|x). We follow Ridolfi (1997) and Ciuperca et al. (2003) to choose

where x ∝ y means that x = cy with a positive constant c independent of any parameter. Note that (5) reduces to the unpenalized likelihood function when a = b = 0. When a > 0 and b > 1, the penalized likelihood approach is equivalent to setting to be the inverse gamma distribution, which is a classical prior distribution for the variance of a normal distribution in Bayesian statistics (Hoff, 2009). We do not impose any prior distribution here. The choice of a and b does not impact the strong consistency of the penalized maximum likelihood estimator (PMLE) based on the same penalty function for a finite mixture of normal distributions (Ciuperca et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2008). Such a penalty performs well in the simulations, though formal proof of the consistency of PMLE for hidden Ising model remains an open question.

We develop an EM algorithm based on the penalized likelihood (5) for the estimation of parameters in the HMRF model characterized by (1)–(3). We introduce unobservable categorical variables K = {Ks: s ∈ S}, where Ks = 0 if Θs = 0, and Ks ∈ {1, …, L} if Θs = 1. Hence, P(Ks=0|Θs=0) = 1 and we denote P(Ks=l|Θs=1) = pl. From (3), we let . To estimate the HMRF parameters Φ = (ϕT, φT)T, (Θ, K, X) are used as the complete data variables to construct the auxiliary function in the (t + 1)st iteration of EM algorithm given the observed data x and the current estimated parameters Φ(t):

where PΦ(Θ, K, X) = Pφ(Θ)Pϕ(X, K|Θ) = Pφ(Θ) Πs∈S Pϕ(Xs, Ks|Θs). The Q-function can be further written as follows

where

and

Therefore, we can maximize Q(Φ|Φ(t)) for Φ by maximizing Q1(ϕ|Φ(t)) for ϕ and Q2(φ|Φ(t)) for φ, separately.

Maximizing Q1(ϕ|Φ(t)) under the constraint by the method of Lagrange multipliers yields,

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where

For Q2(φ|Φ(t)), taking its first and second derivatives with respect to φ, we obtain

Maximizing Q2(φ|Φ(t)) is then equivalent to solving the nonlinear equation:

| (9) |

It can be shown that equation (9) has a unique solution and can be solved by the Newton-Raphson (NR) method (Stoer and Bulirsch, 2002). However, a starting point that is not close enough to the solution may result in divergence of the NR method. Therefore, rather than searching for the solution of equation (9) over all φ, we choose a φ(t+1) that increases Q2(φ|Φ(t)) over its value at φ = φ(t). Together with the maximization of Q1(ϕ|Φ(t)), the approach leads to Q(Φ(t+1)|Φ(t)) ≥ Q(Φ(t)|Φ(t)) and thus pL(Φ(t+1)|x) ≥ pL(Φ(t)|x), which is termed a GEM algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977). To find such a φ(t+1) that increases the Q2-function, a backtracking line search algorithm (Nocedal and Wright, 2006) is applied with a set of decreasing positive values λm in the following

| (10) |

where m = 0, 1, …, and φ(t+1) = φ(t+1,m) which is the first one satisfying the Armijo condition (Nocedal and Wright, 2006)

| (11) |

Since I(φ(t)) is positive-definite, the Armijo condition guarantees the increase of Q2-function. In practice, α is chosen to be quite small. We adopt α = 10−4, which is recommended by Nocedal and Wright (2006), and halve the Newton-Raphson step length each time by using λm = 2−m.

In the GEM algorithm, Monte Carlo averages are used via Gibbs sampler to approximate the quantities of interest that are involved with the intractable normalizing constant of the Ising model. By the ergodic theorem of the Gibbs sampler (Roberts and Smith, 1994) (see Web Appendix D for details),

where {θ(t,1,x), …, θ(t,n,x)} are large n samples successively generated by the Gibbs sampler from

with

and being the normalizing constant, and {θ(1,φ), …, θ(n,φ)} are generated from Pφ(θ). Here for vector v, v⊗2 = vvT. Similarly,

where C is the number of all possible configurations θ of Θ. Then the difference between Q2-functions in the Armijo condition can be approximated by

Back to Q1(ϕ|Φ(t)), the local conditional probability of Θ given x can also be approximated by the Gibbs sampler:

| (12) |

3.2 Implementation of the LIS-Based FDR Procedure

The algorithm for the LIS-based data-driven procedure, denoted as LIS for single group analysis, SLIS for separate analysis of multiple groups, and PLIS for pooled analysis for multiple groups, is given below:

Set initial values Φ(0) = {ϕ(0), φ(0)} for the model parameters Φ of each group;

Update ϕ(t) from equations (6), (7) and (8);

Update φ(t) from equations (10) and (11);

Iterate Steps 2 and 3 until convergence, then obtain the estimate Φ̂ of Φ;

Plug-in Φ̂ to obtain the test statistics from equation (12);

-

Apply the data-driven procedure (LIS, SLIS or PLIS).

The GEM algorithm is stopped when the following stopping rule(13) where Φi is the ith coordinate of vector Φ, is satisfied for three consecutive regular Newton-Raphson iterations with m = 0 in (10), or the prespecified maximum number of iterations is reached. Stopping rule (13) was applied by Booth and Hobert (1999) to the Monte Carlo EM method, where they set ε1 = 0.001, ε2 between 0.002 and 0.005, and the rule to be satisfied for three consecutive iterations to avoid stopping the algorithm prematurely because of Monte Carlo error. We used ε1 = ε2 = 0.001 in simulation studies and real-data analysis. Constant α = 10−4 is recommended by Nocedal and Wright (2006) for the Armijo condition (11), and the Newton-Raphson step length in (10) is halved by using λm = 2−m. In practice, the Armijo condition (11) might not be satisfied when the step length ||φ(t+1,m)− φ(t)|| is very small. In this situation, the iteration within Step 3 is stopped by an alternative criterionwith ε3 < ε2, for example, ε3 = 10−4 if ε2 = 0.001. Small a and b should be chosen in (8). We choose a = 1 and b = 2.

4. Simulation Studies

The simulation setups are similar to those in Sun and Cai (2009) and Wei et al. (2009), but with 3D data. The performances of the proposed LIS-based oracle (OR) and data-driven procedures are compared with the BH approach (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995), the q-value procedure (Storey, 2003), and the local FDR (Lfdr) procedure (Sun and Cai, 2007) for single group analysis; and the performances of SLIS and PLIS are compared with BH, q-value, and the conditional Lfdr (CLfdr) procedure (Cai and Sun, 2009) for multiple groups. The Lfdr and CLfdr procedures are shown to be optimal for independent tests (Sun and Cai, 2007; Cai and Sun, 2009). For simulations with multiple groups, all the procedures are globally implemented using all the locally computed test statistics based on each method from each group. The q-values are obtained using the R package qvalue (Dabney and Storey, 2014). For the Lfdr or CLfdr procedure, we use the proportion of the null cases generated from the Ising model with given parameters as the estimate of the probability of the null cases P(Θs = 0), together with the given null and nonnull distributions without estimating their parameters. For the LIS-based data-driven procedures, the maximum number of GEM iterations is set to be 1,000 with ε1 = ε2 = 0.001, ε3 = α = 10−4, a = 1 and b = 2. For the Gibbs sampler, 5,000 samples are generated from 5,000 iterations after a burn-in period of 1,000 iterations. In all simulations, each HMRF is on a N = 15×15×15 cubic lattice S, the number of replications M = 200 is the same as that in Wei et al. (2009), and the nominal FDR level is set at 0.10.

4.1 Single-Group Analysis

4.1.1 Study 1: L = 1

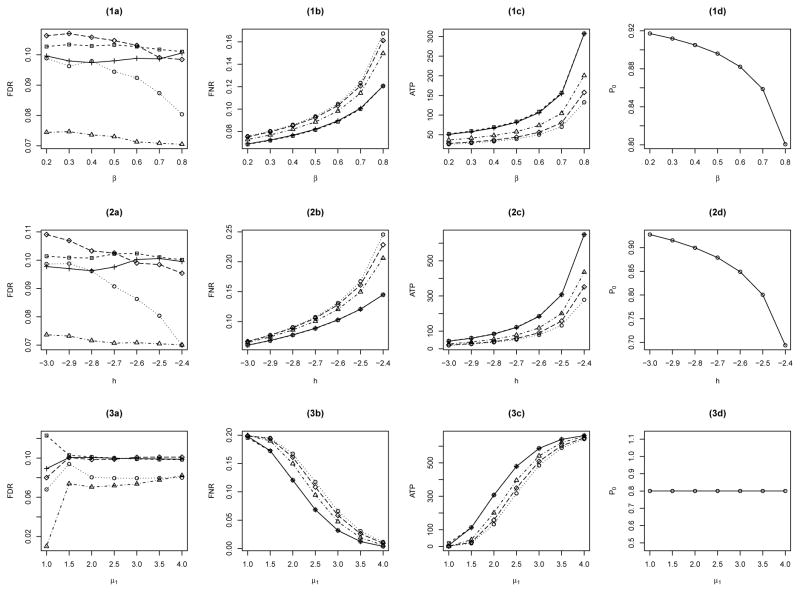

The MRF Θ = {Θs: s ∈ S} is generated from the Ising model (1) with parameters (β, h), and the observations X = {Xs: s ∈ S} are generated conditionally on Θ from . Note that the MRF Θ is not observable in practice. Figure 1 shows the comparisons of the performance of BH, q-value, Lfdr, OR and LIS. In Figure 1(1a–1c), we fix h = −2.5, set μ1 = 2 and , and plot FDR, FNR, and the average number of true positives (ATP) yielded by these procedures as functions of β. In Figure 1(2a–2c), we fix β = 0.8, set μ1 = 2 and , and plot FDR, FNR and ATP as functions of h. In Figure 1(3a–3c), we fix β = 0.8 and h = −2.5, set , and plot FDR, FNR and ATP as functions of μ1. The corresponding average proportions of the nulls, denoted by P0, for each Ising model are given in Figure 1(1d–3d). The initial values for the numerical algorithm are set at β(0) = h(0) = 0, and .

Figure 1.

Comparison of BH (○), q-value (◇), Lfdr (△), OR (+) and LIS (□) for a single group with L = 1.

From Figure 1(1a–3a), we can see that the FDR levels of all five procedures are controlled around 0.10 except one case of the LIS procedure in Figure 1(3a) with the lowest μ1, whereas the BH and Lfdr procedures are generally conservative. This case of obvious deviation of the LIS procedure is likely caused by the small lattice size N. As a confirmation, additional simulations by increasing the lattice size N to 30×30×30 yield an FDR of 0.1019 for the same setup. From Figure 1(1b–3b) and (1c–3c) we can see that the two curves of OR and LIS procedures are almost identical, indicating that the data-driven LIS procedure works equally well as the OR procedure. These plots also show that the LIS procedure outperforms BH, q-value and Lfdr procedures with increased margin of performance in FNR and ATP as β or h increases or μ1 is at a moderate level. Note that from Web Appendix A, we can see that β controls how likely the same-state cases cluster together, and (β, h) together control the proportion of the aggregation of nonnulls relative to that of nulls.

4.1.2 Study 2: L = 2

We now consider the case where the nonnull distribution is a mixture of two normal distributions. The MRF is generated from the Ising model (1) with fixed parameters β = 0.8 and h = −2.5, and the nonnull distribution is a two-component normal mixture with fixed p1 = p2 = 0.5, μ2 = 2, and . In Figure 2(1a–1c), varies from 0.125 to 8, and μ1 = −2. In Figure 2(2a–2c), we fix and vary μ1 from −4 to −1. The initial values are set at β(0) = h(0) = 0, , and , l = 1,2.

Figure 2.

Comparison of BH (○), q-value (◇), Lfdr (△), OR (+) and LIS (□) for a single group with L = 2 (see 1a–2c), and the one with L being misspecified (see 3a–3c).

Similar to Figure 1, we can see that the FDR levels of all the procedures are controlled around 0.10, where BH and Lfdr are conservative, and OR and LIS perform similarly and outperform the other three procedures. In Figure 2(2a) at μ1 = −1, additional simulations yield an FDR of 0.1035 when the lattice size N is increased to 30×30×30 for the same setup.

The results from both simulation studies are very similar to those in Sun and Cai (2009) for the one-dimensional case using HMC. It is clearly seen that, for dependent tests, incorporating dependence structure into a multiple-testing procedure improves efficiency dramatically.

4.1.3 Study 3: misspecified nonnull

Following Sun and Cai (2009), we consider the true nonnull distribution to be the three-component normal mixture 0.4N(μ, 1) + 0.3N(1, 1) + 0.3N(3, 1), but use a misspecified two component normal mixture in the LIS procedure. The unobservable states are generated from the Ising model (1) with fixed parameters β = 0.8 and h = −2.5. The simulation results are displayed in Figure 2(3a–3c), the true μ varies from −4 to −1 with increments of size 0.5. The initial values are set at β(0) = h(0) = 0, , and , l = 1, 2.

Figure 2(3a–3c) shows that the LIS procedure performs similarly to OR under misspecified model. Additionally, the obvious biased FDR level by the LIS procedure at μ = −1 reduces to 0.1067 when the lattice size N is increased to 30×30×30.

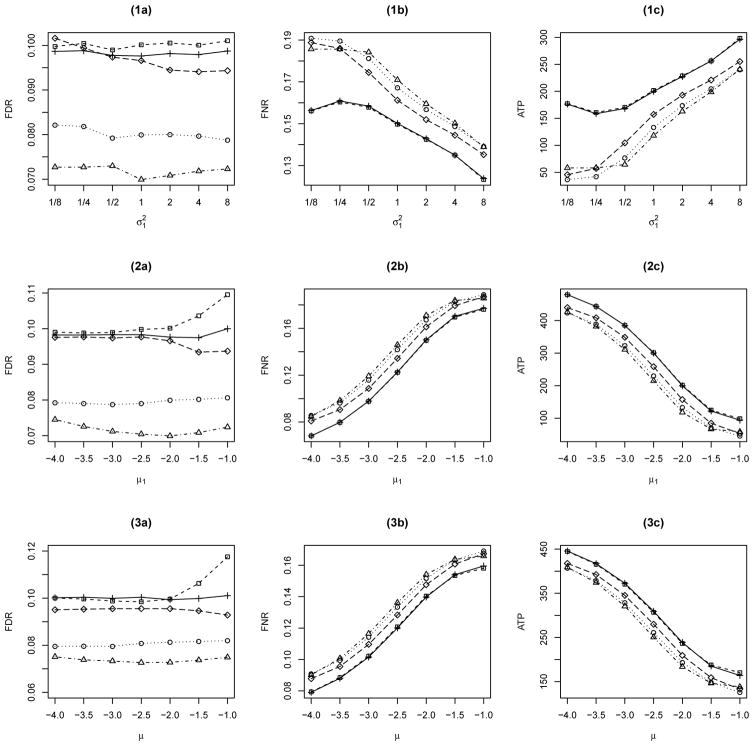

4.2 Multiple-Group Analysis

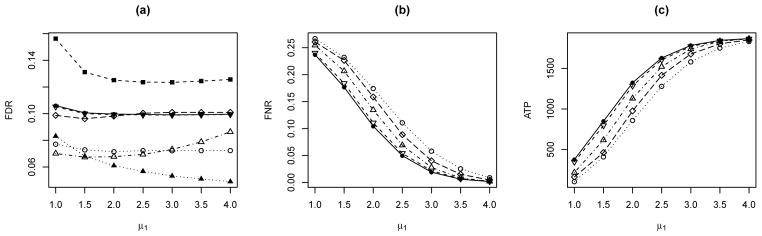

Voxels in a human brain can be naturally grouped into multiple functional regions. For simulations with grouped multiple tests, we consider two lattice groups each with size 15×15×15. The corresponding MRFs Θ1 = {Θ1s: s ∈ S} and Θ2 = {Θ2s: s ∈ S} are generated from the Ising model (1) with parameters (β1 = 0.2, h1 = −1) and (β2 = 0.8, h2 = −2.5), respectively. The observations Xk = {Xks, s ∈ S} are generated conditionally on Θk, k = 1, 2, from , where μ1 varies from 1 to 4 with increments of size 0.5, μ2 = μ1 + 1 and . The initial values are , and .

The simulation results are presented in Figure 3, which are similar to that in Wei et al. (2009) for the one-dimensional case with multiple groups using HMCs. Figure 3(a) shows that all procedures are valid in controlling FDR at the prespecified level of 0.10, whereas BH and CLfdr procedures are conservative. We also plot the within-group FDR levels of PLIS for each group separately. One can see that in order to minimize the global FNR level, the PLIS procedure may automatically adjust the FDRs of each individual group, either in The simulation results are presented in Figure 3, which are similar to that in Wei et al. (2009) for the one-dimensional case with multiple groups using HMCs. Figure 3(a) shows that all procedures are valid in controlling FDR at the prespecified level of 0.10, whereas BH and CLfdr procedures are conservative. We also plot the within-group FDR levels of PLIS for each group separately. One can see that in order to minimize the global FNR level, the PLIS procedure may automatically adjust the FDRs of each individual group, either inflated or deflated reflecting the group heterogeneity, while the global FDR is appropriately controlled. In Figure 3(b) and (c) we can see that both SLIS and PLIS outperform BH, q-value and CLfdr procedures, indicating that utilizing the dependency information can improve the efficiency of a testing procedure, and the improvement is more evident for weaker signals (smaller values of μ1). Between the two LIS-based procedures, PLIS slightly outperforms SLIS, indicating the benefit of ranking the LIS test statistics globally. In particular, ATP is 8.3% higher for PLIS than for SLIS when μ1 = 1.

Figure 3.

Comparison of BH (○), q-value (◇), CLfdr (△), SLIS (▽) and PLIS (●) for two groups with L = 1. In (a), ■ and ▲ represent the results by PLIS for each individual group; for PLIS, while the global FDR is controlled, individual-group FDRs may vary.

5. ADNI FDG-PET Image Data Analysis

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in the elderly population. Much progress has been made in the diagnosis of AD including clinical assessment and neuroimaging techniques. One such extensively used neuroimaging technique is FDG-PET imaging, which is used to evaluate the cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (CMRgl). We consider the FDG-PET image data from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu) as an illustrative example.

The data set consists of the baseline FDG-PET images of 102 normal control (NC) subjects and 206 patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a prodromal stage of AD. Sixty one brain regions of interest (ROIs) are considered (see Web Appendix E for details), where the number of voxels in each region ranges from 149 to 20,680 with a median of 2,517. The total number of voxels of these 61 ROIs is N = 251, 500. The goal is to identify voxels with reduced CMRgl in MCI patients comparing to NC.

We apply the HMRF-PLIS procedure to the ADNI data, and compare to BH, q-value and CLfdr procedures. We implement the BH procedure globally for the 61 ROIs, whereas we treat each region as a group for the q-value, CLfdr and PLIS procedures. For the BH and q-value procedures, a total number of N two-sample Welch’s t-tests (Welch, 1947) are performed, and their corresponding two-sided p-values are obtained. For the PLIS and CLfdr procedures, z-values are used as the observed data x, which are obtained from those t statistics by the transformation zi = Φ−1[G0(ti)], where Φ and G0 are the cumulative distribution functions of the standard normal and the t statistic, respectively. The null distribution is assumed to be the standard normal distribution. The nonnull distribution is assumed to be a two-component normal mixture for PLIS. The LIS statistics in the PLIS procedure are approximated by 106 Gibbs-sampler samples, and the Lfdr statistics in the CLfdr procedure are computed by using the R code of Sun and Cai (2007). All the four testing procedures are controlled at a nominal FDR level of 0.001. In the GEM algorithm for HMRF estimation, the initial values for β and h in the Ising model are set to be zero. The initial values for the nonnull distributions are estimated from the signals claimed by BH at an FDR level of 0.1. The maximum number of GEM iterations is set to be 5,000 with ε1 = ε2 = 0.001, ε3 = α = 10−4, a = 1 and b = 2. For the Gibbs sampler embedded in the GEM, 5,000 samples are generated from 5,000 iterations after a burn-in period of 1,000 iterations. In this data analysis, the GEM algorithm reaches the maximum iteration and is then claimed to be converged for five ROIs. Among all 61 ROIs, the estimates of β have a median of 1.57 with the interquartile range of 0.36, and the estimates of h have a median of −3.71 with the interquartile range of 1.52. Such magnitude of parameter variation supports the multi-region analysis of the ADNI FDG-PET image data because even a 0.1 difference in β or h can result in quite different Ising models, see Figure 1(1d) and (2d).

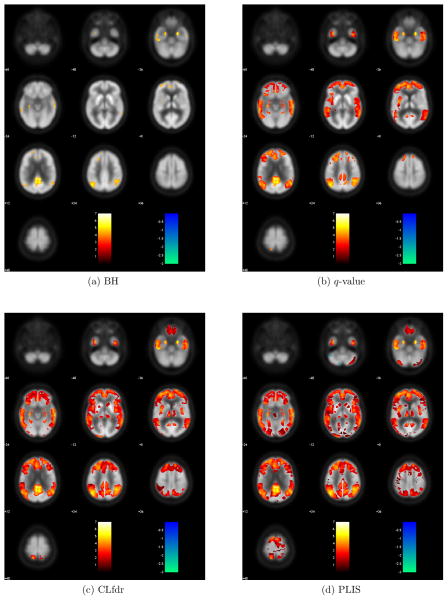

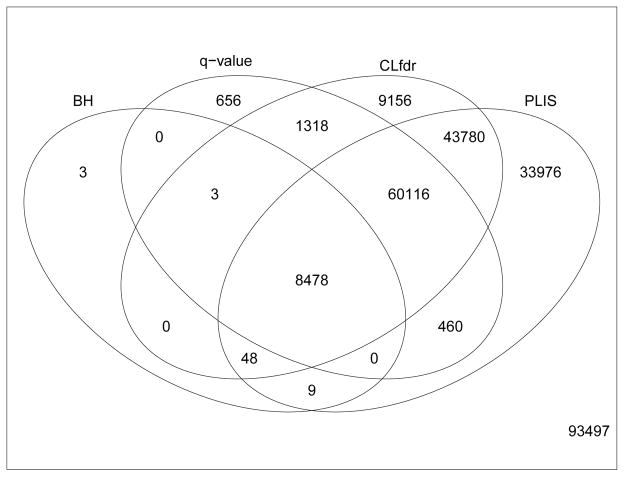

Figure 4 shows the z-values (obtained by comparing CMRgl values between NC and MCI) of all the signals claimed by each procedure. Figure 5 summarizes the number of voxels that are claimed as signals by each procedure. We can see that PLIS finds the largest number of signals and covers 91.5%, 97.2% and 99.9% of signals detected by CLfdr, q-value and BH, respectively. It is interesting to see that the PLIS procedure finds more than 17 times signals as BH, twice as many signals as q-value, and about 20% more signals than the CLfdr procedure.

Figure 4.

Z-values of the signals found by each procedure for the comparison between NC and MCI.

Figure 5.

Venn diagram for the number of signals found by each procedure for the comparison between NC and MCI. Number of signals discovered by each procedure: BH=8,541, q-value=71,031, CLfdr=122,899, and PLIS=146,867.

Detailed interpretations of the scientific findings are provided in Web Appendix E.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this article, we consider LIS-based FDR procedures based on HMRF for 3D neuroimage data, where HMRF provides a natural way of modeling spatial correlations. The procedures aim to minimize the FNR while FDR is controlled at a prespecified level. We find brain regions are spatially heterogeneous, hence model each region separately by a single HMRF, and implement the PLIS procedure to minimize the global FNR. We propose a GEM algorithm based on the penalized likelihood to obtain the HMRF parameter estimates, which overcomes the unboundedness of the original likelihood function. Numerical analysis shows the superiority of the HMRF-LIS-based procedures over commonly used FDR procedures, illustrating the value of HMRF-LIS-based FDR procedures for spatially correlated image data. The asymptotic properties of the PMLE of HMRF and the data-driven HMRF-LIS- based procedures are of interest for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Jeanine Houwing-Duistermaat, an Associate Editor and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. The research is supported in part by NIH grant R01-AG036802 and NSF grants DMS-1007590 and DMS-1407142.

We also would like to thank ADNI for providing the brain image data that were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). Data collection and sharing was funded by NIH grant U01-AG024904 and DOD grant W81XWH-12-2-0012. ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare;; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Web Appendix A mentioned in Sections 2 and 4, Web Appendices B–D referenced in Section 3, Web Appendix E mentioned in Section 5, and a MATLAB package implementing the proposed FDR procedure are available with this paper at the Biometrics website on Wiley Online Library.

References

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. On the adaptive control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing with independent statistics. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2000;25:60–83. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. The Annals of Statistics. 2001;29:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Booth JG, Hobert JP. Maximizing generalized linear mixed model likelihoods with an automated Monte Carlo EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1999;61:265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bremaud P. Markov Chains: Gibbs Fields, Monte Carlo Simulation, and Queues. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Sun W. Simultaneous testing of grouped hypotheses: Finding needles in multiple haystacks. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2009;104:1467–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Chandgotia N, Han G, Marcus B, Meyerovitch T, Pavlov R. One-dimensional Markov random fields, Markov chains and topological Markov fields. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 2014;142:227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Tan X, Zhang R. Inference for normal mixtures in mean and variance. Statistica Sinica. 2008;18:443–465. [Google Scholar]

- Chumbley JR, Friston KJ. False discovery rate revisited: FDR and topological inference using Gaussian random fields. NeuroImage. 2009;44:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumbley J, Worsley K, Flandin G, Friston K. Topological FDR for neuroimaging. NeuroImage. 2010;49:3057–3064. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciuperca G, Ridolfi A, Idier J. Penalized maximum likelihood estimator for normal mixtures. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 2003;30:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dabney A, Storey JD. qvalue: Q-value estimation for false discovery rate control. R package version 1.36.0 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Large-scale simultaneous hypothesis testing: The choice of a null hypothesis. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2004;99:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Farcomeni A. Some results on the control of the false discovery rate under dependence. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 2007;34:275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Garey LJ. Brodmann’s Localisation in the Cerebral Cortex. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Geman S, Geman D. Stochastic relaxation, Gibbs distributions, and the Bayesian restoration of images. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 1984;6:721–741. doi: 10.1109/tpami.1984.4767596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. NeuroImage. 2002;15:870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese C, Wasserman L. Operating characteristics and extensions of the false discovery rate procedure. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2002;64:499–517. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese C, Wasserman L. A stochastic process approach to false discovery control. The Annals of Statistics. 2004;32:1035–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff PD. A First Course in Bayesian Statistical Methods. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Goldsmith J, Reiss PT, Reich DS, Crainiceanu CM. Bayesian scalar-on-image regression with application to association between intracranial DTI and cognitive outcomes. NeuroImage. 2013;83:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TD, Liu Z, Bartsch AJ, Nichols TE. A Bayesian non-parametric Potts model with application to pre-surgical FMRI data. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2013;22:364–381. doi: 10.1177/0962280212448970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magder LS, Zeger SL. A smooth nonparametric estimate of a mixing distribution using mixtures of Gaussians. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:1141–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Nocedal J, Wright S. Numerical Optimization. 2. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ridolfi A. Politecnico di Milano. Milan; Italy: 1997. Maximum likelihood estimation of hidden Markov model parameters, with application to medical image segmentation. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GO, Smith AFM. Simple conditions for the convergence of the Gibbs sampler and Metropolis-Hastings algorithms. Stochastic Processes and their Applications. 1994;49:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stoer J, Bulirsch R. Introduction to Numerical Analysis. 3. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD. The positive false discovery rate: A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. The Annals of Statistics. 2003;31:2013–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Cai TT. Oracle and adaptive compound decision rules for false discovery rate control. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2007;102:901–912. [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Cai TT. Large-scale multiple testing under dependence. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2009;71:393–424. doi: 10.1111/rssb.12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Sun W, Wang K, Hakonarson H. Multiple testing in genome-wide association studies via hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2802–2808. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch BL. The generalization of ‘Student’s’ problem when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika. 1947;34:28–35. doi: 10.1093/biomet/34.1-2.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler G. Image Analysis, Random Fields and Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods. 2. New York: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu WB. On false discovery control under dependence. The Annals of Statistics. 2008;36:364–380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Fan J, Yu T. Multiple testing via FDR L for large-scale image data. The Annals of Statistics. 2011;39:613–642. doi: 10.1214/10-AOS848SUPP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Johnson TD, Little RJA, Cao Y. Quantitative magnetic resonance image analysis via the EM algorithm with stochastic variation. The Annals of Applied Statistics. 2008;2:736–755. doi: 10.1214/07-AOAS157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.