Abstract

Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) signaling in response to flagellin is dispensable for inducing humoral immunity, but alterations of aa 89–96, the TLR5 binding site, significantly reduced the adjuvanticity of flagellin. These observations indicate that the underlying mechanism remains incompletely understood. Here, we found that the native form of Salmonella typhimurium aa 89–96-mutant flagellin extracted from flagella retains some TLR5 recognition activity, indicating that aa 89–96 is the primary, but not the only site that imparts TLR5 activity. Additionally, this mutation impaired the production of IL-1β and IL-18. Using TLR5KO mice, we found that aa 89–96 is critical for the humoral adjuvant effect, but this effect was independent of TLR5 activation triggered by this region of flagellin. In summary, our findings suggest that aa 89–96 of flagellin is not only the crucial site responsible for TLR5 recognition, but is also important for humoral immune adjuvanticity through a TLR5-independent pathway.

Keywords: adjuvanticity, amino acids 89–96, Salmonella typhimurium flagellin, TLR5 activity

Introduction

Flagellin is a unique type of inflammatory molecule that is a ligand of both Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) and the Nod-like receptor NLRC4.1,2,3,4,5 Activation of TLR5 can induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α and KC, whereas the recognition of intracellular flagellin by NLRC4 results in the maturation and secretion of the inflammasome cytokines IL-1β and IL-18.6,7

It has been reported that amino acid (aa) 89–96 of flagellin encompasses the TLR5 ligand activity site and that the replacement of aa 89–96 of the Salmonella typhimurium gene fliC with the Helicobacter pylori gene flaA completely abolishes the TLR5-dependent activity of the protein.8 Analysis of the crystal structure of zebrafish TLR5, which was crystallized in complex with the D1/D2/D3 fragment of Salmonella flagellin, showed that the deletion of the LRR9 loop of TLR5, corresponding to aa 89–96 in the flagellin ligand, severely impairs the induction of TLR5 signaling by two to three orders of magnitude.9 However, the extent to which aa 89–96 affects the TLR5 ligand activity of flagellin has not yet been fully elucidated.

Additionally, flagellin has been shown to be an effective adjuvant in many systems,10,11,12 and it is generally thought that flagellin exerts its adjuvant effects through TLR5 activation,13 with a large number of pro-inflammatory cytokines being elicited in this process. Furthermore, the substitution of aa 89–96 of flagellin abolished its adjuvant effect.14 However, the adjuvant humoral immune response was not altered when flagellin mixed with OVA protein was administered to immunized TLR5KO mice, indicating that the TLR5-mediated innate immune response is not necessary for the adjuvant effect of flagellin.15,16 These studies also showed that the deletion of the hypervariable region in flagellin decreases the potency of the protein for generating antagonistic antibodies.14 Moreover, antibodies against the TLR5 ligand activity site of flagellin prevent infected flagellated bacteria from recognition by host cell innate immune sensors.17

Thus, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between TLR5 recognition activity and the adjuvant activity of aa 89–96 in flagellin. Additionally, the role of the hypervariable region of flagellin in innate and adaptive immune responses was also examined.

Materials and methods

Materials

pTrc99a (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) was kindly provided by E L Hartland of the University of Melbourne (Victoria, Australia). Salmonella typhimurium strain LB5000 was a gift from L R Bullas of Loma Linda University (Loma Linda, CA, USA).18 Salmonella Dublin strain SL1438 (ATCC39184) was donated by B A Stocker of Stanford University (Palo Alto, CA, USA). The Salmonella typhimurium strains ATCC14028s and ATCC14028s (fliC−fljB−) were kindly donated by K D Smith of the Institute for Systems Biology (Seattle, WA, USA).19 Crystallized chicken egg white albumin (OVA, Grade VI, St. Louis, MO, USA) was purchased from Sigma, and the inactivated vaccine strain H5N1 Re-6 of avian influenza virus was purchased from the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute (Harbin, China).

Mice

Six- to eight-week-old female wild-type (WT) and TLR5KO C57BL/6 mice were provided by the Animal Center of the Institut Pasteur (Paris, France), and the Comparative Medicine Centre of Yangzhou University (Yangzhou, China). The care and use of the mice was approved by the respective institutional animal experimentation committee (the Direction Départementale des Services Vétérinaires de la Préfecture de Police de Paris and the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Yangzhou University). All surgeries were performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Creation of flagellin substitution and deletion mutants

We amplified fliC-WT from Salmonella typhimurium (ATCC14028s) and cloned it into the NcoI and HindIII sites of the pTrc99a plasmid. For flagellin variants with the I411A mutation (pTrc99a-fliC-411), an aa 89–96 fliC→flaA substitution (pTrc99a-fliC-89–96) or the Δ183–279 mutant (pTrc99a-fliC-SJW61),8,20,21 their DNA sequences were generated from fliC-WT using a standard PCR-based mutagenesis strategy.22 All mutations were then verified by DNA sequencing. The corresponding plasmids were electrically transformed into the intermediate host bacterium S. typhimurium strain LB5000 for modification, then into the final host strain S. typhimurium ATCC14028s (fliC−fljB−) for expression. Additionally, the 89–96 fliC→flaA substitution mutant was cloned into the NcoI and HindIII sites of the pET30a plasmid (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) and transformed into Escherichia coli BL-21 (DE3) for protein production (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA).

The expression of mutant flagellin proteins in both the ATCC14028s (fliC−fljB−) and E. coli BL-21 (DE3) transformants were induced with 1 mM IPTG. Proteins were analyzed using standard SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting with rabbit anti-Hi antiserum (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) and a goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

Electron microscopy

Samples were negatively stained with 2% (w/v) phosphotungstic acid that was neutralized to pH 7.4 with 1 M KOH. Electron micrographs were obtained using a Philips Tecnai 12 electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, the Netherlands).

Serological identification and bacterial motility assays

The ATCC14028s (fliC−fljB−) transformants were identified using the conventional slide agglutination test with Difco Salmonella O and H antisera (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA), then were ‘stab-inoculated' into the centers of motility plates (LB medium containing 0.3% agar, 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG). The cultures were incubated upright at 37 °C for 6 h and were then photographed.

Purification and preparation of bacterial flagellin

The ATCC14028s (fliC−fljB−) transformants were cultured in the presence of 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG; this is a well-established method to obtain the monomeric flagellin that was used for the extraction.23 The 6×-His flagellin protein expressed from pET30a was purified under native conditions using the Novagen His Bind Purification Kit. The flagellin proteins were transferred into 20K MWCO Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassettes (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), and dialysis was conducted for 18 h at 4 °C with constant stirring in 4 l of PBS. ProteoSpin Endotoxin Removal Maxi Kits (Norgen Biotek, Thorold, ON, Canada) were first used to concentrate the flagellin and remove contaminants. Then, purified proteins were cycled through a Pierce High-Capacity Endotoxin Removal Spin Column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) several times until the final EU concentration was below 0.1 EU/µg protein. The endotoxin level was measured using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate QCL-1000 assay (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD, USA). Residual DNA was detected using DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit I (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and N-terminal sequencing of flagellin was performed by PPSQ-33A (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using the Edman degradation method. The total protein concentration was determined using the Bradford dye-binding method (Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit II, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

TLR5 activation assay

HEK293-mTLR5 cells stably transfected with murine TLR5 (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) were cultured in DMEM/high-glucose medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) in the presence of 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), Normocin (100 µg/ml; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) and the selective antibiotic blasticidin (10 µg/ml; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). WT HEK293 cells were cultured without blasticidin as indicated above.

For IL-8 assays, 5×104 cells/well were seeded into a flat-bottom 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C in an incubator with 5 % CO2 overnight. The cells were washed twice and stimulated for 5 h with each mutant flagellin. The amount of human IL-8 secreted into the supernatant was quantified by ELISA (BD OptEIA Human IL-8 ELISA Set).

For the NF-κB activation assay, HEK293-mTLR5 cells were transfected with pNiFty-SEAP (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA), which encodes an SEAP reporter under the control of an NF-κB-dependent ELAM promoter. The cells were plated in 96-well flat-bottom plates at a density of 5×104 cells/well. On the day of stimulation, cells were washed twice and then stimulated with each mutant flagellin, trypsin-treated mock flagellin14 or a flagellin-mimic control (the same extraction protocol was used with the ATCC14028s flagellin-deficient (fliC−fljB−) strain) for 20 h. The SEAP levels were determined with a spectrophotometer using the QUANTI-Blue system (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Ex vivo production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 by peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) in response to mutant flagellin proteins

Resident peritoneal macrophages were collected from euthanized C57BL/6 mice by RPMI-1640 lavage. Peritoneal cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS. For the IL-1β assay, PECs were seeded at a density of 2×105 cells/ml and stimulated with the mutant flagellin proteins or each control for 24 h.13 The IL-1β secreted into the supernatant was quantified by ELISA (BD OptEIA Mouse IL-1β ELISA Set). For the IL-18 assay, PECs were seeded at a density of 4×105 cells/ml and stimulated as described for IL-1β the secreted IL-18 was quantified using a Mouse IL-18 ELISA Kit (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA).

Quantification of serum cytokine levels

One hour after i.p. injection with a 1-µg dose of each mutant flagellin,24 blood was collected from the retrobulbar intraorbital capillary plexus. The serum was separated, and levels of IL-6, TNFα, IL-1β and IL-18 were quantified using the BD OptEIA ELISA Set and Invitrogen Mouse IL-18 ELISA Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunizations

Six- to eight-week-old C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.p. with OVA (50 µg) alone or OVA (50 µg) mixed with a purified flagellin protein in PBS (total volume, 200 µl). Subsequently, serum antibody titers were measured by ELISA.15 Similarly, C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.p. with the inactivated vaccine strain H5N1 Re-6 virions (0.2 µg) alone or mixed with a purified flagellin protein in PBS (total volume, 200 µl), and the serum HI titers were measured according to OIE procedures. Blood was collected from the retrobulbar intraorbital capillary plexus, and the sera were stored at −80 °C until use.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant differences were detected using the Mann–Whitney U test. Differences for which P<0.05 were considered to be significant and were indicated by asterisks in the text. All statistical values were calculated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

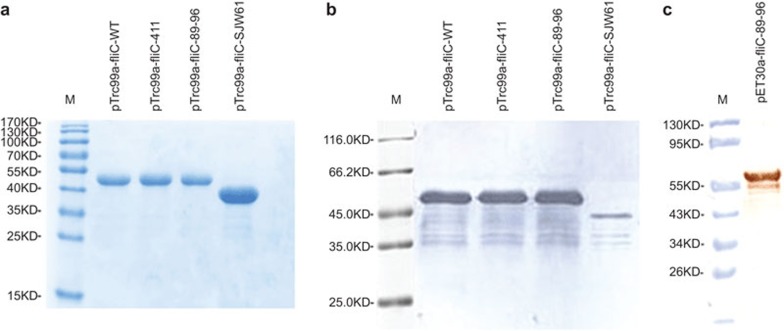

The aa 89–96 fliC→flaA mutant flagellin retains detectable TLR5 recognition activity

A series of flagellated recombinant Salmonella strains were constructed to determine whether the TLR5 ligand activity site (aa 89–96), the aa (411th) that most affects TLR5-dependent activity of flagellin and the hypervariable region of flagellin could affect recognition by TLR5.8,14,20 The flagellated strains were photographed (Supplementary Figure 1a), and flagellar motilities (Supplementary Figure 1b) and serological patterns (Table 1) were also examined. We found that the flagellin proteins expressed by pTrc99a were successfully assembled into flagella and all of the flagellated recombinant strains could be agglutinated using Salmonella Hi antisera in the slide agglutination test, indicating that the flagella were fully functional. Then, all mutant flagellin proteins from Salmonella and the pET30a-expressed soluble fusion flagellin proteins from E. coli were characterized (Figure 1). Residual DNA was measured and found to be less than 1 pg/µg protein (Supplementary Figure 2). The N-terminal sequence of all four flagellin proteins from Salmonella was AQVINTNSLSLLTQN as predicted (Supplementary Figure 3).

Table 1. Serological identification of the recombinant Salmonella strains.

| Group | O4 | Hi | O9 | Hg,p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC14028s | − | + | + | − |

| ATCC14028s (fliC−fljB−) | − | − | + | − |

| SL1438 | − | − | + | + |

| ATCC14028s (pTrc99a-fliC-WT) | − | + | + | − |

| ATCC14028s (pTrc99a-fliC-411) | − | + | + | − |

| ATCC14028s (pTrc99a-fliC-89–96) | − | + | + | − |

| ATCC14028s (pTrc99a-fliC-SJW61) | − | + | + | − |

Figure 1.

Characterization of mutant flagellin proteins. (a) SDS–PAGE analysis of the recombinant mutant flagellin proteins expressed from pTrc99a. (b) Western blot analysis of the recombinant mutant flagellin proteins expressed from pTrc99a. (c) Western blot analysis of the aa 89–96 fliC→flaA mutant flagellin protein expressed from pET30a. M indicates the molecular size markers in kDa.

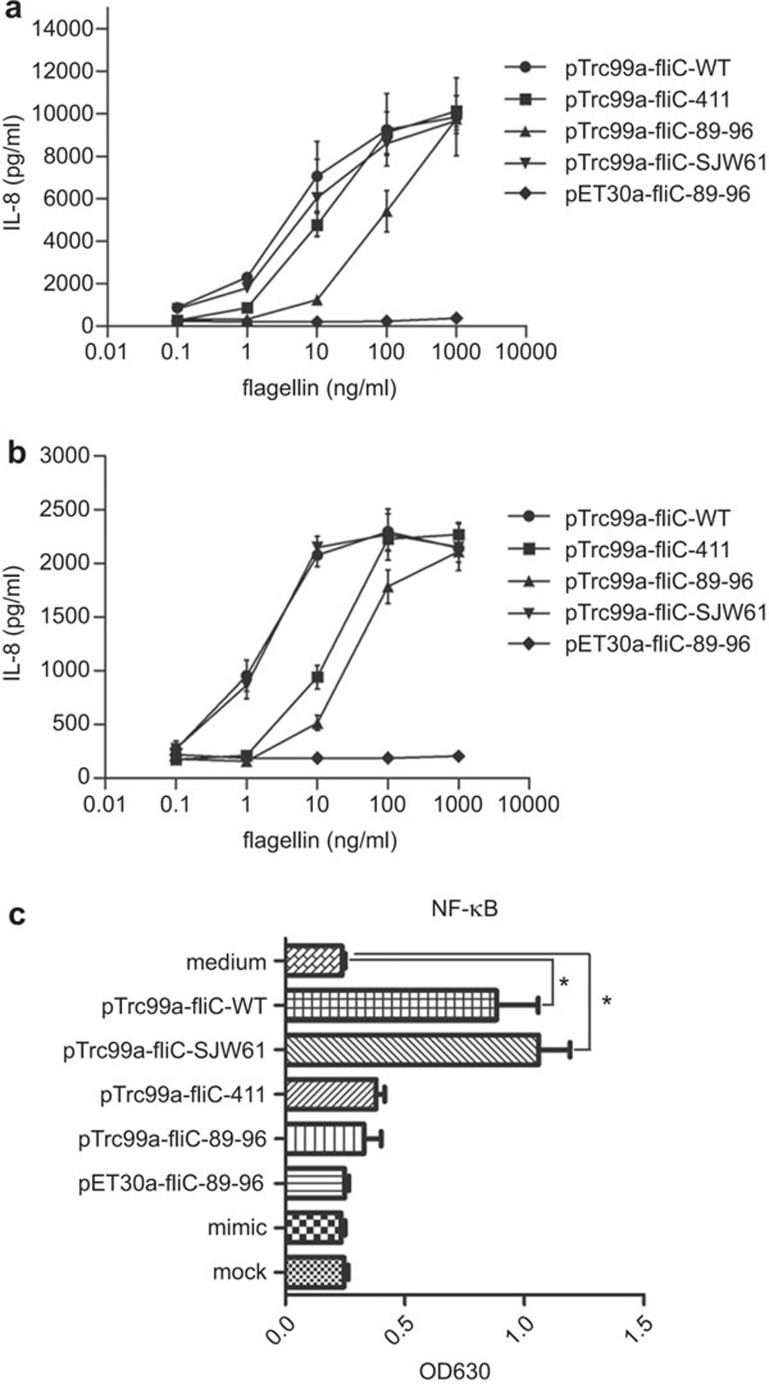

In IL-8 assay, we found that the difference in IL-8 secretion was most obvious at low stimuli concentrations in HEK293-mTLR5 cells, but all of the native flagellin proteins extracted from Salmonella induced the maximum amount of IL-8 secretion at stimuli concentrations greater than 1 µg/ml (Figure 2a). As a control, markedly reduced IL-8 secretion was observed in WT HEK293 cells (Figure 2b). This finding was supported by the results of an NF-κB activation assay (Figure 2c). In summary, our findings suggested that the TLR5 recognition activity of the pET30a-fliC-89–96 flagellin was completely lost, whereas the pTrc99a-fliC-89–96 flagellin retained some, albeit reduced TLR5 recognition activity. The I411A mutation in flagellin significantly affected TLR5 recognition, although mutating the hypervariable region of flagellin had no effect on TLR5 recognition. Notably, the removal of the His-tag of the pET30a-fliC-89–96 fusion protein did not affect TLR5 recognition (data not shown). The mock and mimic flagellins that we used as controls activated neither TLR5 nor NF-κB.

Figure 2.

TLR5 dose–response curves to the purified recombinant mutant flagellin proteins. (a) Dose–response curve of IL-8 production by HEK293-mTLR5 cells stimulated with purified recombinant mutant flagellin proteins at concentrations of 0.1–1000 ng/ml. (b) Dose–response curves of IL-8 production by wild-type HEK293 cells stimulated with purified recombinant mutant flagellin proteins at concentrations of 0.1–1000 ng/ml. (c) NF-κB pathway activation in response to stimulation with the recombinant mutant flagellin proteins. Cells were stimulated 0.5 ng/ml flagellin. Data are presented as the means±s.d. of three independent experiments that we performed in triplicate. Error bars represent one s.d. Statistical analyses were done using Mann–Whitney analysis relative to the unstimulated well; *P<0.05. TLR, Toll-like receptor.

TLR5 recognition of flagellin induces pro-inflammatory cytokine production and deletion of the flagellin hypervariable region enhances inflammatory cytokine secretion

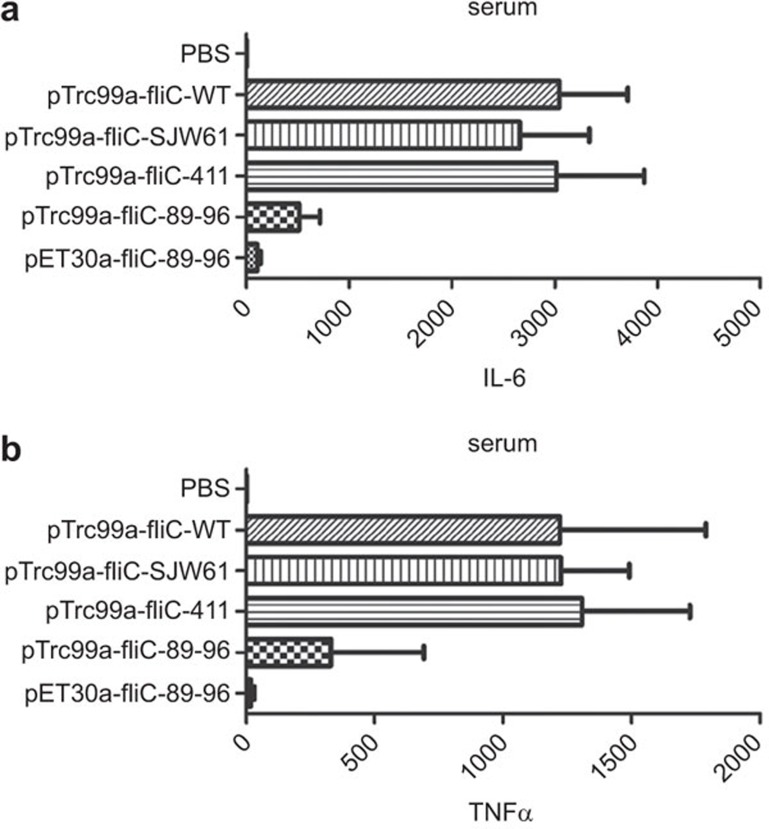

Bacterial flagellin elicits widespread innate immune responses, leading to the release of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines that allow it to act as a critical mediator of systemic inflammation.24 In this study, intraperitoneal injection of the I411A or SJW61 mutant flagellins triggered secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, but the aa 89–96 fliC→flaA mutant flagellin did not evoke substantial IL-6 or TNF-α production (Figure 3), Additionally, inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18, were not detected in the serum. These results indicated that TLR5 recognition of flagellin was responsible for the enhanced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and that the inflammatory responses were inhibited in the process. The robust cytokine secretion by I411A mutant flagellin suggested that the TLR5 signal strength triggered by stimuli at the microgram levels had reached the cytokine secretion threshold.

Figure 3.

IL-6 and TNF-α pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in mouse serum induced by flagellin. One hour after i.p. injection with 1-µg dose mutant flagellin protein, sera were collected for ELISA. Error bars represent one s.d. Data are presented as the means±s.d. of three independent experiments. N=5 mice per group. (a) IL-6. (b) TNF-α.

Additionally, TLRs can stimulate the production of the proforms of the cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, whereas certain NLRs can trigger subsequent proteolytic processing of these proforms via caspase 1.25 To evaluate these inflammatory molecules, PECs were collected from euthanized mice. Flow cytometric analysis showed that 77.4% of the PECs were F4/80+CD11b+ (data not shown). In the murine PEC model, we found that TLR5 recognition of flagellin promoted the secretion of mature IL-1β and IL-18. Flagellin SJW61, in which aa 183–279 in the hypervariable region were deleted, evoked significantly enhanced secretion of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 (Figure 4). These results indicated that TLR5 and NLRC4 work collaboratively in the innate immune response and that the partial deletion of the hypervariable region in flagellin enhances the inflammatory response.

Figure 4.

Deletion of the hypervariable region in flagellin significantly enhances the secretion of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 by ex vivo stimulated PECs. Each mutant flagellin was prepared 10 µg/ml concentration, except for the mutant flagellin pTrc99a-fliC-SJW61 (7.73 µg/ml), and cells were stimulated for 24 h. Data are presented as the means±s.d. of three independent experiments that were performed in triplicate. Error bars represent one s.d. Statistical analyses were done using Mann–Whitney analysis; *P<0.05. (a) IL-1β inflammatory cytokine production. (b) IL-18 inflammatory cytokine production. PEC, peritoneal exudate cell.

Reduction in TLR5 recognition and the partial deletion the hypervariable region in flagellin do not impair its humoral adjuvanticity

Flagellin has adjuvant activity. To better characterize this property, we empirically determined the minimal immunization dose of flagellin that is required to evoke a maximal adjuvant effect. We found that a 0.5 µg dose of the pTrc99a-expressed flagellin was sufficient. Next, we examined the adjuvant effect in the groups of mice immunized with mutant flagellin proteins mixed with OVA protein or with the inactivated vaccine strain H5N1 Re-6 (Figure 5). In both flagellin expression systems, we found that neither the deletion of the hypervariable region of the flagellin protein nor flagellin with a modestly reduced TLR5 recognition activity affected adjuvant activity. By contrast, the aa 89–96 fliC→flaA substitution partially reduced the adjuvanticity of flagellin; the mock and mimic flagellins showed no adjuvanticity.

Figure 5.

The adjuvant activity of mutant flagellin proteins expressed from pTrc99a. (a) Comparison of the adjuvant activities of the groups immunized with 0.5 µg pTrc99a-expressed flagellin mixed with 50 µg OVA. Mice were immunized with OVA alone or with 50 µg of OVA and a mutant flagellin protein on days 0 and 14. OVA-specific IgG titers were assayed on day 28 by ELISA. (b) A comparison of the adjuvant activities of the groups immunized with pTrc99a-expressed mutant flagellins mixed with inactivated H5N1 vaccine strain virions. Mice were immunized with H5N1 Re-6 alone or were co-injected with 0.2 µg H5N1 Re-6 and 0.5 µg mutant flagellin on days 0 and 14. The HA titer was assayed on day 28. Lines indicate the arithmetic means. Each point represents the serum HI titer for an individual mouse. Error bars represent one s.d. Data are presented as the means±s.d. of three independent experiments. N=5 mice per group. Statistical analyses were performed using Mann–Whitney analysis; *P<0.05.

aa 89–96 of flagellin is the key site responsible for adjuvanticity in humoral immunity but is independent of the characteristics of TLR5 binding

Previous studies have shown that aa 89–96 of Salmonella Typhimurium flagellin comprise the critical activity site of this TLR5 ligand. Here, we used C57BL/6 TLR5KO and C57BL/6 WT mice to compare the adjuvant effects of WT and aa 89–96 fliC→flaA flagellin (Figure 6). We found that in both strains of mice, the group co-injected with pTrc99a-fliC-89–96 and OVA protein had significantly lower OVA-specific IgG titers than the group co-injected with pTrc99a-fliC-WT and OVA protein; however, the titers were still higher than the group injected with OVA alone, suggesting that the adjuvant ability of Salmonella typhimurium flagellin does not require its TLR5 ligand activity, but that the aa 89–96 substitution in flagellin significantly reduced its adjuvanticity. In conclusion, these results indicate that aa 89–96 of flagellin represent the key site responsible for the adjuvant effect in humoral immunity, but this is not related to typical TLR5 binding.

Figure 6.

The amino acids 89–96 of flagellin represents the key site for the adjuvant effect in humoral immunity, but is independent of typical TLR5 binding characteristics. A comparison of the adjuvant activities in mice immunized with 20 µg pTrc99a-fliC-89–96 flagellin or pTrc99a-fliC-WT flagellin mixed with 50 µg OVA in TLR5KO and WT mice. Mice were injected on days 0 and 14. OVA-specific IgG titers were measured on day 28 by ELISA. Data are presented as the means±s.e.m. of two independent experiments. Error bars represent one s.d. Statistical analyses were carried out using Mann–Whitney analysis; *P<0.05. For PBS-treated TLR5KO mice, n=3 per group; for other cohorts, n=5 per group.

Discussion

In this study, we constructed four flagellated recombinant Salmonella strains. We found that the E. coli-expressed aa 89–96 fliC→flaA flagellin completely lacked TLR5 recognition activity; however, the native conformation of aa 89–96 fliC→flaA flagellin extracted from flagella retained detectable TLR5 recognition activity, which indicated that E. coli-expressed flagellin may not fully reflect the characteristics of native flagellin. This finding was in accordance with a recent study that found that the absence of the TLR5 LRR9 loop severely impaired TLR5 signaling.9

Additionally, the innate immune response characteristic of each mutant flagellin was analyzed both ex vivo and in vivo. In contrast to the TLR5 ligand binding site, which is mainly located in the D1 domain, the inflammasome-stimulating site of flagellin proteins is located in the C-terminal leucine-rich helical hairpin region.26,27 In a murine PEC model, we found that TLR5 recognition or the deletion of the hypervariable region of flagellin significantly promoted the secretion of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. Recent studies have demonstrated the dependence of IL-1β production on TLR5 signaling by alveolar macrophages and the requirement for TLR5 to induce IL-1β mRNA expression in the intestine.28,29 IL-18 induction by flagellin is generally thought to be mediated by the NLRC4 inflammasome, which does not require TLR5. We hypothesized the reduced IL-18 induction by the replacement of aa 89–96 fliC→flaA in flagellin may be a consequence of impaired NLRC4 activity. Interestingly, the TLR5 activity of the Δ183–279 flagellin mutant was not altered, but the inflammatory responses were stronger. We also observed this effect in the His-tagged Δ183–279 flagellin mutant. We attributed these effects to the lower MW of this flagellin, which facilitates phagocytosis into the cytoplasm for the activation of the NLRC4 inflammasome (data not shown).

Flagellin has intrinsic adjuvant activities that have been widely reported.13,30 In this study and in the work of Nempont et al.,14 it was found that aa 89–96 of flagellin is critical for adjuvant effects, and this eight conserved aa sequence is also crucial for flagellar filament formation.8 As shown in electron micrographs of the recombinant Salmonella strains, the aa 89–96 fliC→flaA flagellum was much shorter and more fragile than the other flagella. It resulted in 10-fold lower yields of flagellin extraction compared to other mutant flagellins. In TLR5KO and WT mice, the similarly decreased adjuvant effects for aa 89–96 mutant flagellin indicated that another factor might be involved at the TLR5 binding site. The reduced IL-1β and IL-18 production in Figure 4 may explain the reason why this decreased adjuvanticity was observed. We hypothesized that the NLRC4 activity is also impaired. Interestingly, Lopez-Yglesias et al.31 recently reported that a MyD88-independent pathway contributes to the adjuvanticity of flagellin towards OVA protein. They proposed that this pathway contributes to both the recognition and adjuvanticity of flagellin. Our data indicate that aa 89–96 of flagellin should be considered as a candidate domain that triggers this novel pathway.

Many studies have investigated the influence of the TLR5 binding site and the deletion of the hypervariable domain of flagellin on its adjuvanticity. It has been reported that vaccines against flagellated pathogens should avoid inducing antibodies against the TLR5 ligand activity site; as such, antibodies may allow flagellated bacteria to evade the host innate immune response.17 Additionally, it has been reported that the deletion of the hypervariable region in flagellin promotes escape from neutralization by decreasing the potency of the protein that is the target of antagonistic antibodies.14 In this study, we demonstrated that the reduced TLR5 recognition or the deletion of the partial hypervariable domain in flagellin did not affect the adjuvant activity of the protein when administered i.p. The adjuvanticity of flagellin was also confirmed using a foreign Ag, an H5N1 vaccine strain, and flagellin showed a remarkable adjuvant effect. Therefore, these constructs may be suitable in the clinic for the delivery of flagellin as an adjuvant.

In conclusion, we confirmed the relationship between TLR5 recognition activity and adjuvant activity of aa 89–96 in flagellin. Although many basic questions and the potential uses of flagellin as an adjuvant remain to be explored, based on its remarkable adjuvanticity, we believe that flagellin has the potential to be used as a next-generation vaccine adjuvant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB518805), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31230070, 31172299), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-12-0745) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). We thank XiaoMing Zhang of Institut Pasteur in Paris for assistance with in vivo studies and for critically reading this manuscript, and Edith Deriaud of Institut Pasteur in Paris for technical assistance.

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cellular & Molecular Immunology's website. (http://www.nature.com/cmi).

Supplementary Information

References

- 1Donnelly MA, Steiner TS. Two nonadjacent regions in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli flagellin are required for activation of Toll-like receptor 5. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 40456–40461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Eaves-Pyles TD, Wong HR, Odoms K, Pyles RB. Salmonella flagellin-dependent proinflammatory responses are localized to the conserved amino and carboxyl regions of the protein. J Immunol 2001; 167: 7009–7016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Murthy KG, Deb A, Goonesekera S, Szabo C, Salzman AL. Identification of conserved domains in Salmonella muenchen flagellin that are essential for its ability to activate TLR5 and to induce an inflammatory response in vitro. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 5667–5675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Lightfield KL, Persson J, Brubaker SW, Witte CE, von Moltke J, Dunipace EA et al. Critical function for Naip5 in inflammasome activation by a conserved carboxy-terminal domain of flagellin. Nat Immunol 2008; 9: 1171–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Miao EA, Andersen-Nissen E, Warren SE, Aderem A. TLR5 and Ipaf: dual sensors of bacterial flagellin in the innate immune system. Semin Immunopathol 2007; 29: 275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Strindelius L, Filler M, Sjoholm I. Mucosal immunization with purified flagellin from Salmonella induces systemic and mucosal immune responses in C3H/HeJ mice. Vaccine 2004; 22: 3797–3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7McSorley SJ, Cookson BT, Jenkins MK. Characterization of CD4+ T cell responses during natural infection with Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol 2000; 164: 986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Andersen-Nissen E, Smith KD, Strobe KL, Barrett SL, Cookson BT, Logan SM et al. Evasion of Toll-like receptor 5 by flagellated bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 9247–9252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Yoon SI, Kurnasov O, Natarajan V, Hong M, Gudkov AV, Osterman AL et al. Structural basis of TLR5-flagellin recognition and signaling. Science 2012; 335: 859–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Newton SM, Jacob CO, Stocker BA. Immune response to cholera toxin epitope inserted in Salmonella flagellin. Science 1989; 244: 70–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Taylor DN, Treanor JJ, Sheldon EA, Johnson C, Umlauf S, Song L et al. Development of VAX128, a recombinant hemagglutinin (HA) influenza-flagellin fusion vaccine with improved safety and immune response. Vaccine 2012; 30: 5761–5769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Zhang H, Liu L, Wen K, Huang J, Geng S, Shen J et al. Chimeric flagellin expressed by Salmonella typhimurium induces an ESAT-6-specific Th1-type immune response and CTL effects following intranasal immunization. Cell Mol Immunol 2011; 8: 496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Mizel SB, Bates JT. Flagellin as an adjuvant: cellular mechanisms and potential. J Immunol 2010; 185: 5677–5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Nempont C, Cayet D, Rumbo M, Bompard C, Villeret V, Sirard, JC. Deletion of flagellin's hypervariable region abrogates antibody-mediated neutralization and systemic activation of TLR5-dependent immunity. J Immunol 2008; 181: 2036–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Sanders CJ, Franchi L, Yarovinsky F, Uematsu S, Akira S, Nunez G et al. Induction of adaptive immunity by flagellin does not require robust activation of innate immunity. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39: 359–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Vijay-Kumar M, Carvalho FA, Aitken JD, Fifadara NH, Gewirtz AT. TLR5 or NLRC4 is necessary and sufficient for promotion of humoral immunity by flagellin. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40: 3528–3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Saha S, Takeshita F, Matsuda T, Jounai N, Kobiyama K, Matsumoto T et al. Blocking of the TLR5 activation domain hampers protective potential of flagellin DNA vaccine. J Immunol 2007; 179: 1147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Bullas LR, Ryu JI. Salmonella typhimurium LT2 strains which are r- m+ for all three chromosomally located systems of DNA restriction and modification. J Bacteriol 1983; 156: 471–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Raffatellu M, Chessa D, Wilson RP, Dusold R, Rubino S, Baumler AJ. The Vi capsular antigen of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi reduces Toll-like receptor-dependent interleukin-8 expression in the intestinal mucosa. Infect Immun 2005; 73: 3367–3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Smith KD, Andersen-Nissen E, Hayashi F, Strobe K, Bergman MA, Barrett SL et al. Toll-like receptor 5 recognizes a conserved site on flagellin required for protofilament formation and bacterial motility. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Yoshioka K, Aizawa S, Yamaguchi S. Flagellar filament structure and cell motility of Salmonella typhimurium mutants lacking part of the outer domain of flagellin. J Bacteriol 1995; 177: 1090–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Smith KD, Valenzuela A, Vigna JL, Aalbers K, Lutz CT. Unwanted mutations in PCR mutagenesis: avoiding the predictable. PCR Methods Appl 1993; 2: 253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Ibrahim GF, Fleet GH, Lyons MJ, Walker RA. Method for the isolation of highly purified Salmonella flagellins. J Clin Microbiol 1985; 22: 1040–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Rolli J, Loukili N, Levrand S, Rosenblatt-Velin N, Rignault-Clerc S, Waeber B et al. Bacterial flagellin elicits widespread innate immune defense mechanisms, apoptotic signaling, and a sepsis-like systemic inflammatory response in mice. Crit Care 2010; 14: R160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: guardians of cytosolic sanctity. Immunol Rev 2009; 227: 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Miao EA, Mao DP, Yudkovsky N, Bonneau R, Lorang CG, Warren SE et al. Innate immune detection of the type III secretion apparatus through the NLRC4 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 3076–3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Poyraz O, Schmidt H, Seidel K, Delissen F, Ader C, Tenenboim H et al. Protein refolding is required for assembly of the type three secretion needle. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010; 17: 788–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Descamps D, Le Gars M, Balloy V, Barbier D, Maschalidi S, Tohme M et al. Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5), IL-1beta secretion, and asparagine endopeptidase are critical factors for alveolar macrophage phagocytosis and bacterial killing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 1619–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Carvalho FA, Aitken JD, Gewirtz AT, Vijay-Kumar M. TLR5 activation induces secretory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (sIL-1Ra) and reduces inflammasome-associated tissue damage. Mucosal Immunol 2011; 4: 102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30McSorley SJ, Ehst BD, Yu Y, Gewirtz AT. Bacterial flagellin is an effective adjuvant for CD4+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol 2002; 169: 3914–3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Lopez-Yglesias AH, Zhao X, Quarles EK, Lai MA, VandenBos T, Strong RK et al. Flagellin induces antibody responses through a TLR5- and inflammasome-independent pathway. J Immunol 2014; 192: 1587–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.