Abstract

γδ T cells play important roles in innate immunity as the first-line of defense against infectious diseases. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection disrupts the balance between Vδ1 T cells and Vδ2 T cells and causes dysfunction among γδ T cells. However, the biological mechanisms and clinical consequences of this disruption require further investigation. In this study, we performed a comprehensive analysis of phenotype and function of memory γδ T cells in cohorts of Chinese individuals with HIV infection. We found a dynamic change in memory Vδ2 γδ T cells, skewed toward an activated and terminally differentiated effector memory phenotype TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cell, which may account for the dysfunction of Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV disease. In addition, we found that IL-17-producing γδ T cells were significantly increased in HIV-infected patients with fast disease progression and positively correlated with HLA-DR+ γδ T cells and CD38+HLA-DR+ γδ T cells. This suggests the IL-17 signaling pathway is involved in γδ T-cell activation and HIV pathogenesis. Our findings provide novel insights into the role of Vδ2 T cells during HIV pathogenesis and represent a sound basis on which to consider immune therapies with these cells.

Keywords: γδ T cell, HIV, IL-17, immune activation, memory Vδ2 γδ T cells

Introduction

γδ T cells represent a small population (1%–10%) of the lymphocyte pool.1 Unlike conventional αβ T cells bearing αβ T-cell receptors (TCRs), γδ T cells function in an MHC-independent manner and play a vital role in the first line of host defense against infectious diseases.2,3 In humans, two major subsets of γδ T cells, Vδ1 and Vδ2, have been defined based on the δ chain usage. Vδ1 T cells bearing Vδ1-encoded TCRs predominately reside in specific tissues such as intestine and spleen and respond to stress-induced antigens including MHC class 1-related chain A/B and UL16-binding proteins.4,5,6 In contrast, Vδ2 T cells bearing Vδ2-encoded TCRs account for the major circulating pool of γδ T cells and significantly expand in response to phosphoantigens during a variety of infectious diseases.7,8,9

The balance between Vδ1 T cells and Vδ2 T cells is altered in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients, with increasing Vδ1 T cells and a substantial depletion of Vδ2 T cells.10,11,12,13 Vδ2 T-cell numbers correlate directly with CD4+ T-cell counts and inversely with viral loads.14 The capacity of Vδ2 T cells to respond to phosphoantigens, such as isopentenyl pyrophosphate, inversely correlates with HIV-1 disease progression due to the specific depletion of the Vγ2Jγ1.2 Vδ2 T-cell subpopulation.12,15 However, the mechanisms and clinical consequences for this remain unclear.

Given that most Vδ2 T cells are CD4− and resistant to HIV infection,16 the loss of Vδ2 T cells is likely an indirect effect of HIV infection. Following HIV infection, progression to AIDS is typically associated with chronic immune activation that gradually depletes the naïve CD4+ T- and CD8+ T-cell pools and subsequently impairs the immune function of HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.17,18,19 To date, the contribution of Vδ2 T-cell depletion in chronic immune activation has not been comprehensively investigated in HIV infection. In this study, we performed a comprehensive phenotypic and functional analysis of memory γδ T cells in cohorts of Chinese individuals with acute and chronic HIV infection in different stages of progression to define the specificity of Vδ2 T-cell depletion and the functional changes in the γδ subsets. Our efforts constitute a critical step toward identifying key mechanisms and clinical consequences of Vδ2 T-cell depletion in HIV infection. Our findings may help elucidate the role that Vδ2 T cells play in HIV pathogenesis and may provide a sound basis on which to consider immune therapies using these cells.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

One hundred and one HIV-infected patients were enrolled in this study. Most of the patients were from the acute HIV infection (Beijing PRIMO) cohort20,21 and the chronic HIV infection cohort from 2006–2012, Beijing You'An Hospital, China. HIV infection was defined by HIV-specific antibody, HIV RNA and western blotting (WB). Patients were divided into four groups: an acute HIV infection group (ACUTE), a slow progression group (SP), a fast progression group (FP) and a HAART group (HAART). Acute HIV-infected patients (ACUTE, n=17) were defined as negative in the presence of HIV antibody but positive for HIV RNA.22 The average infection time of acute HIV-infected patients was 59 (59±35.38) days. Patients with progressive disease with less than 350 CD4+ cells/µl and requiring highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) according to the WHO recommendation within 2 years after diagnosis were classified as fast progressors (FPs, n=21), and those who did not require HAART (greater than 350 CD4+ cells/µl) within 2 years were defined as slow progressors (SPs, n=37).23 Patients who received HAART therapy, using a first-line regimen of zidovudine, lamivudine and efavirenz were defined as the HAART group (n=26). Patients with opportunistic infections or co-infections with tuberculosis, hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus were excluded in this study. Twenty-six age-matched healthy subjects were recruited as healthy controls. The characteristics of all patients are described in Table 1 and Table 2. This study was approved by the Beijing You'An Hospital Research Ethics Committee with written informed consent obtained from each participant.

Table 1. General information of chronic HIV-infected patients in the study.

| Characteristics | HC group | Acute group | SP group | FP group | HAART group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 26 | 17 | 37 | 21 | 26 |

| Chinese Han population (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Age (years), mean±s.d. | 28.6±5.9 | 28.9±7.07 | 32.3±11.6 | 30.5±7.8 | 32.3±11.4 |

| Male (%) | 80.5 | 100 | 91.2 | 95.2 | 84.6 |

| Transmission, homosexual (%) | — | 100 | 83.8 | 90.5 | 65.3 |

| CD4 cell count (cells/µl), mean±s.d. | 891±543 | 447±166 | 506±128 | 248±58 | 350±179 |

| CD8 cell count (cells/µl), mean±s.d. | 788±441 | 1277±730 | 1006±370 | 871±375 | 837±418 |

| Plasma viral load (log10 copies/ml), mean±s.d. | NA | 4.7±1.13 | 3.57±1.62 | 3.83±1.22 | 1.12±0.38 |

Abbreviations: FP, fast progressors; HC, healthy control; NA, not applicable; SP, slow progressor.

Data were shown as mean±s.d.

Table 2. CD4 cell counts from ten patients before and after therapy in HAART group.

| Before HAART | After HAART | |

|---|---|---|

| PT1 | 49 | 103 |

| PT2 | 87 | 154 |

| PT3 | 50 | 164 |

| PT4 | 57 | 108 |

| PT5 | 19 | 142 |

| PT6 | 150 | 202 |

| PT7 | 106 | 281 |

| PT8 | 180 | 297 |

| PT9 | 176 | 329 |

| PT10 | 119 | 232 |

Abbreviations: HAART, highly activate antiretroviral therapy; PT, patient.

Cell counting

CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts were measured with a FACSCalibur TruCount tube Becton Dickinson (San Diego, CA, USA) with multicolor antibodies (CD3+, CD8+, CD45+ and CD4+ T cells). The results were analyzed by Multiset software BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA).

Viral load testing

Plasma viral load was analyzed by the Roche Cobas Amplicor 2.0 assay (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), which has a lower limit of detection of 50 copies/ml.

Antibodies

Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human CD38 (HIT2) monoclonal antibody (mAb), allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human HLA-DR (L243) mAb, phycoerythrin-cyanine 7 (PE-cy7)-conjugated anti-human CD3 (HIT3a) mAb, peridinin-chlorophyll-protein complex cyanine 5.5 (PerCP-cy5.5)-conjugated anti-human CD27 (O323) mAb and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human CD45RA (HI100) mAb were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-human pan TCRγδ mAb, PE-conjugated anti-human pan TCRγδ (IMMU510) mAb and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-human pan Vδ2TCR (IMMU389) were purchased from Immunotech (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, France). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-human pan Vδ1TCR (TS8.2) mAb was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). PE-conjugated IL-17A (SCPL1362) mAb and PE-conjugated interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (B27) mAb were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). The isotype control mAbs were purchased from the corresponding company, respectively.

Flow cytometry analysis

For surface staining, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from healthy controls and HIV-infected patients as described previously.24,25 Briefly, the cells were washed with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin before labeling with specific antibodies. For intracellular staining, cells were incubated with 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate, 1 µg/ml ionomycin and 5 µg/ml Brefeldin A (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), followed by fixation, permeabilization and incubation with specific antibodies. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACScan flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Version 7.6.2; Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Quantification of plasma lipopolysaccharide (LPS), LPS-binding protein (LBP) and soluble CD14 (sCD14)

Plasma LPS was quantified using the limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Hycult Biotech, Uden, The Netherlands) as described previously.26 Briefly, plasma samples from HIV-infected patients and healthy controls were diluted 1∶10 with endotoxin-free water and then inactivated for 5 min at 75 °C before incubation with limulus amebocyte lysate reagent for 30 min at room temperature. The enzyme reaction was stopped with acetic acid, and the absorbance measured at 405 nm. The levels of sCD14 and LBP in plasma were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits from R&D Systems ( Minneapolis, MN, USA) and Cell Sciences (Canton, MA, USA), respectively.27 All operations were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean±s.d. One-way ANOVA, the Mann–Whitney U test and Spearman's rank-correlation were performed for data analysis using Prism 5.0 software.

Results

HIV infection disrupts the balance of circulating γδ T-cell subsets

We performed a series of flow cytometry analyses to compare the proportions of circulating γδ T-cell subsets in HIV-infected patients. We found that both the frequency and the absolute number of total peripheral blood γδ T cells were not significantly changed among the healthy controls (n=20), ACUTE (n=12), SP (n=22), FP (n=17) and HAART (n=21) groups (Figure 1a–c). However, compared with healthy controls, the proportions and the absolute numbers of Vδ1 γδ T cells were significantly increased in all HIV-infected groups, with the highest levels in the FP group (Figure 1d and e). In contrast, the proportions and the absolute numbers of Vδ2 γδ T cells in all HIV-infected patient groups were significantly decreased compared to healthy controls (Figure 1d and e), but with no significant differences among the ACUTE, SP and FP groups. In addition, the ratios of Vδ1 γδ/Vδ2 γδ T cells were reversed in all HIV-infected groups (Figure 1f). Taken together, these results suggest that HIV infection disrupts the balance of circulating γδ T-cell subsets, with a specific depletion of Vδ2 γδ T cells. Interestingly, our results show HAART treatment did not restore the depletion of Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients (Figure 1d and e).

Figure 1.

HIV infection disrupts the balance of γδ T-cell subsets. PBMCs were isolated from HCs, ACUTE, SP, FP and HAART groups, and the proportions and numbers of γδ T cells were assessed by flow cytometry. (a) γδ T cells were gated, and the proportions of Vδ1 and Vδ2 γδ T cells were analyzed; (b) percentages of γδ T cells; (c) absolute numbers of γδ T cells; (d) percentages of Vδ1 and Vδ2 γδ T cells; (e) absolute numbers of Vδ1 and Vδ2 γδ T cells; (f) ratios of Vδ1/Vδ2 γδ T cells. Significant differences and P values were determined by the Mann–Whitney U test or by one-way ANOVA. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001. HC, healthy control; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Memory Vδ2 γδ T cells are skewed toward a TEMRA phenotype in HIV infection

The specific depletion of Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients led us to analyze the proportions of Vδ2 γδ T-cell subsets by measuring expression levels of cell surface markers CD27 and CD45RA (Figure 2a). Our results show that the frequency of naïve Vδ2 γδ T cells (CD27+CD45RA+, Tnaive) was dramatically decreased in HAART compared with the healthy controls, ACUTE and SP groups (Figure 2b). Interestingly, the frequency of Tnaive Vδ2 γδ T cells in the SP group was higher than that in the FP group (Figure 2b). In addition, the frequency of central memory Vδ2 γδ T cells (CD27+CD45RA−, TCM) was decreased in all HIV-infected patients groups compared with healthy controls (Figure 2c). We also found a significant decrease in TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells in the FP group compared with that of the SP group (Figure 2c), suggesting the depletion of TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells accelerates the progression of HIV disease. However, the frequency of TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells in the HAART group was still lower than the healthy controls, indicating that HAART therapy could not restore the TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells (Figure 2c). Further, the effector memory (CD27−CD45RA−, TEM) Vδ2 γδ T cells were significantly decreased in the acute HIV-infected patients compared with healthy controls. However, no difference was found between the SP group and the FP group (Figure 2d). Strikingly, we observed a dramatic increase in terminally differentiated effector memory TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells in all HIV-infected patients, especially in the acute and the FP groups (Figure 2e). This dynamic change indicates that HIV infection drives the Vδ2 γδ T cells toward a terminally differentiated effector phenotype, which subsequently results in the dysfunction of Vδ2 γδ T cells.

Figure 2.

Memory Vδ2 γδ T cells in chronic HIV infection. Comparisons of Vδ2 γδ T-cell subsets among the HCs, ACUTE, SP, FP and HAART groups. (a) Vδ2 γδ T cells were gated, and the expression of CD27 and CD45RA were analyzed. (b) Tnaive Vδ2 γδ T cells; (c) TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells; (d) TEM Vδ2 γδ T cells; (e) TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells. Significant differences and P values were determined by one-way ANOVA. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001. HC, healthy control.

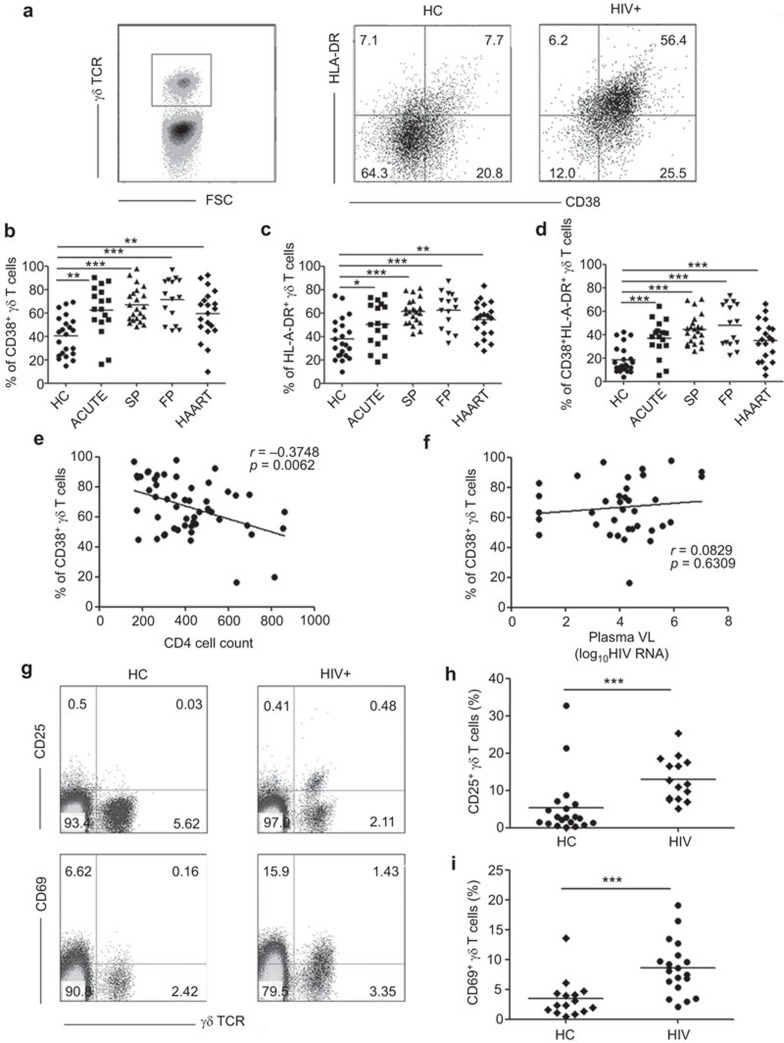

Elevated activation of γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients

Previous studies demonstrate a persistent activation of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in chronic HIV-infected patients.28,29,30 Here, we investigated whether γδ T cells were also overactivated in HIV-infected patients with different disease progressions by measuring the expression levels of activation markers CD38 and HLA-DR using flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 3a, levels of CD38 and HLA-DR expressed on γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients were significantly higher than in healthy controls. The frequencies of CD38+γδ T cells and HLA-DR+ γδ T cells were significantly elevated in all HIV-infected groups compared with the healthy controls (Figure 3b and c). The frequency of CD38+HLA-DR+ γδ T cells was also increased in all HIV-infected patients (Figure 3d). No significant differences were observed in the frequencies of activated γδ T cells among the HIV-infected groups (Figure 3b–d). We then analyzed the correlation of γδ T-cell activation with the CD4+ T-cell counts and the viral loads in HIV-infected patients. The results show that the frequency of CD38+γδ T cells displayed a negative correlation with the CD4+ T-cell count, but no correlation with the plasma viral load in HIV-infected patients (Figure 3e–f). Moreover, we also found significant increases in the expression of CD25 and CD69 on γδ T cells in acute HIV-infected patients compared with healthy controls (Figure 3g–i). Taken together, these results suggest that excessive activation of γδ T cells occurs during the early phase of HIV disease and is associated with disease progression. HAART treatment has no significant effect on this activation.

Figure 3.

γδ T cells are excessively activated in HIV-infected patients. (a) γδ T cells were gated, and the expression of CD38 and HLA-DR were analyzed by flow cytometry. Comparisons of the frequencies of (b) CD38+ γδ T cells, (c) HLA-DR+ γδ T cells and (d) CD38+HLA-DR+ γδ T cells among the HCs, ACUTE, SP, FP and HAART groups. Correlation analysis of the frequency of CD38+ γδ T cells with (e) CD4+ T-cell counts and (f) plasma viral loads. (g) Lymphocytes were gated, and the expression of CD25 and CD69 on γδ T cells from HCs (n=19) and ACUTE (n=15) were analyzed by flow cytometry. Comparisons of the frequencies of (h) CD25+γδ T cells and (i) CD69+γδ T cells between the HCs and ACUTE groups. Significant differences and P values were calculated by the Mann–Whitney U tests and one-way ANOVA. Correlations were determined by Spearman's rank correlation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001. HC, healthy control.

Microbial translocation contributes to elevated activation of γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients

Microbial translocation contributes to chronic immune activation in HIV-infected patients, especially toward CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells.31,32,33 LPS, a marker of microbial translocation, positively correlates with CD8+ T-cell activation.27 LBP is a serum glycoprotein that initiates an immune response after recognition of bacterial LPS in vivo.34 sCD14 in plasma, driven predominantly by microbial translocation, affects the activation status of T cells.32 Here, we investigated whether microbial translocation contributes to γδ T-cell activation in HIV-infected patients.

We measured three biomarkers, LPS, LBP and sCD14, associated with microbial translocation in the plasma samples from healthy controls and the HIV-infected patients with different disease progressions. The results show that plasma LPS was increased in the early stages of HIV disease (ACUTE and SP groups), but decreased in the HAART group (Figure 4a). Additionally, we found a slight increase in plasma levels of LBP in the SP and HAART groups compared with the healthy controls (Figure 4b). Plasma levels of sCD14 were significantly elevated in all HIV-infected patients, especially in the FP and HAART groups, compared with healthy controls (Figures 4c). These data suggest that microbial translocation predominantly exists in chronic HIV-infected patients. Furthermore, we observed a significant positive correlation between the frequencies of HLA-DR+ γδ T cells and sCD14 (Figure 4h). However, there was no significant correlation between the frequencies of CD38+ γδ T cells or CD38+HLA-DR+γδ T cells and sCD14 (Figure 4g and i). Additionally, no significant correlation was found between any subset of Vδ2 γδ T cells and sCD14 levels in untreated HIV-infected patients (Figure 4j–m). Together, these results suggest that microbial translocation contributes to elevated activation of γδ T cells in chronic HIV-infected patients.

Figure 4.

Microbial translocation contributes to elevated activation of γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients. ELISA analysis on the levels of (a) LPS, (b) LBP and (c) sCD14 in the plasma of the HCs, ACUTE, SP, FP and HAART groups. Correlation analysis of the frequencies of CD38+γδ T cells, HLA-DR+ γδ T cells and CD38+HLA-DR+γδ T cells with the levels of (d–f) LBP and (g–i) sCD14. Correlation analysis (j–m) shows no significant correlation between the sCD14 levels and the frequency of any subset of Vδ2 γδ T cells in untreated HIV-infected patients. Significant differences and P values were calculated by the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations were determined by Spearman's rank correlation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HC, healthy control; LBP, LPS- binding protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; sCD14, soluble CD14.

Chronic immune activation depletes memory Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients

The finding of elevated activation of γδ T cells prompted us to investigate whether chronic immune activation contributes to the depletion of Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients. We measured CD38 expression on different Vδ2 γδ T cell subsets (Tnaive, TCM, TEM and TEMRA) by flow cytometry. Our results show the levels of CD38 expression on all Vδ2 γδ T-cell subsets were significantly increased in all HIV-infected groups compared with healthy controls (Figure 5a), indicating that all Vδ2 γδ T cells display an elevated activation in HIV-infected patients.

Figure 5.

Chronic immune activation distorts memory Vδ2 γδ T cells towards terminally differentiated effector TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients. (a) Comparison of CD38 expression levels in the subsets of Vδ2 γδ T cells in the HCs, ACUTE, SP, FP and HAART groups. Correlation analyses of the frequency of CD38+ γδ T cells with the frequencies of Vδ2 γδ T-cell subsets (b) Tnaive Vδ2 γδ T cells, (c) TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells, (d) TEM Vδ2 γδ T cells and (e) TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells. Significant differences and P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA. Correlations were determined by Spearman's rank correlation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001. HC, healthy control.

We then analyzed the correlations between the frequencies of Vδ2 γδ T-cell subtypes and the proportion of CD38+γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients. We found no significant correlation between the frequency of Tnaïve Vδ2 γδ T cells and CD38+γδ T cells (Figure 5b). Our findings show that the frequencies of TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells and TEM Vδ2 γδ T cells were negatively correlated to the frequency of CD38+γδ T cells (Figure 5c and d). These data suggest that the depletion of memory Vδ2 γδ T cells may result from excessive immune activation of γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients. Interestingly, we found a positive correlation between the frequency of TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells and the frequency of CD38+γδ T cells (Figure 5e), indicating that HIV infection causes an increase in excessively activated TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells.

IL-17-producing γδ T cells were significantly increased in chronic HIV-infected patients

IFN-γ and IL-17 are two important immunoregulatory cytokines in innate immunity against virus and intracellular pathogens.3,35 The imbalanced production of cytokines by T cells is associated with the activation and exhaustive status of memory T cells in HIV-infected patients.36 Here, we assessed the production of IL-17 and IFN-γ by γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients with different disease progressions. After gating on lymphocytes, IL-17 or IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells were analyzed in the healthy controls, ACUTE, SP, FP and HAART groups (Figure 6a). We found that the frequency of IL-17-producing γδ T cells was increased in the ACUTE and SP groups and significantly increased in the FP groups, compared with the healthy controls (Figure 6b). Moreover, HAART treatment reduced the frequency of IL-17-producing γδ T cells to nearly the same level as in the healthy controls (Figure 6b). These results suggest that IL-17-producing γδ T cells are involved in HIV disease progression. However, no significant differences in IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells among the healthy controls, ACUTE, SP, FP and HAART groups were found (Figure 6c). Correlation analysis also showed significant positive correlations between the frequency of IL-17-producing γδ T cells and the frequencies of HLA-DR+ γδ T cells (Figure 6e) and CD38+HLA-DR+ γδ T cells (Figure 6f), but not with the frequency of CD38+ γδ T cells (Figure 6d). These results suggest that HIV-1 infection directly distorts the production of cytokines in γδ T cells and that IL-17-producing γδ T cells may play an important role in HIV pathogenesis and disease progression.

Figure 6.

The balance of cytokine production by γδ T cells is disrupted in HIV-infected patients. PBMCs (2×106/well) were seeded into 24-well plates, stimulated with PMA (50 ng/ml)/Ion (1 µg/ml) for 6 h before the addition of BFA (10 µg/ml). After incubation for 2 hours, intracellular staining of IFN-γ and IL-17 was assessed by flow cytometry. (a) IL-17-producing γδ T cells and IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (b, c) Quantitative comparisons of IL-17-producing γδ T cells and IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells among the HCs, ACUTE, SP, FP and HAART groups. (d–f) The frequency of IL-17 producing γδ T cells was positively correlated to (e) HLA-DR+ γδ T cells and (f) CD38+HLA-DR+ γδ T cells but not to (d) CD38+γδ T cells. Significant differences and P values were calculated by the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations were determined by Spearman's rank correlation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. HC, healthy control; Ion, ionomycin; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate.

Discussion

The loss of Vδ2 T cells is an early characteristic event in HIV disease progression. In agreement with previous reports,11,12,13 we found that HIV infection caused a significant increase in Vδ1 T cells and a sharp decrease in Vδ2 T cells, leading to an inverted Vδ2/Vδ1 ratio in all HIV-infected patients, including acute HIV-infected patients, slow progressors and fast progressors. The decrease of Vδ2 γδ T cells was positively correlated to the CD4+ cell count, but not correlated to viral RNA (data not shown), which was different from a previously published paper from China.14 This discrepancy may be due to the different HIV strains or transmission routes. Consistent with previous data,37 we show that HAART therapy did not rescue the loss of Vδ2 γδ T cells. However, Chaudhry et al.38 recently reported that prolonged antiretroviral therapy can reconstitute the Vγ2 T-cell receptor repertoire. To date, the mechanisms of Vδ2 γδ T-cell depletion are not clear. Li and Pauza39 reported that HIV envelope glycoproteins could induce uninfected cell apoptosis through the Erk and Akt kinase pathways. In addition, Herbeuval et al.40 have reported that type I IFN-regulated TRAIL/DR5 mechanisms induce apoptosis of CD4+ T cells. Similarly, we found that TRAIL/DR5 expression in Vδ2 γδ T cells in acute HIV-infected patients was significantly increased compared with healthy controls (data not shown). This indicates that the IFN-regulated TRAIL/DR5 mechanisms engage in the depletion of Vδ2 γδ T cells. More studies should be conducted to clarify the mechanisms of HIV-mediated depletion of Vδ2 γδ T cells.

In this study, our comprehensive analysis of memory Vδ2 γδ T cells in cohorts of Chinese individuals shows for the first time that naive Vδ2 γδ T cells are not decreased at the acute stage (ACUTE group) of HIV infection, but are significantly reduced in fast progressors (FP group). TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells (CD27+CD45RA−), abundant in peripheral blood, were significantly depleted in fast progressors. TEM Vδ2 γδ T cells were only significantly decreased in acute HIV-infected patients. Moreover, we found that HAART treatment could not restore the proportion of TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells, although it could restore the proportion of TEM Vδ2 γδ T cells to similar levels in healthy controls. In contrast, there was a significant increase in the frequency of TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients, especially in acute HIV-infected patients and fast progressors compared with healthy controls. These dynamic changes in memory Vδ2 γδ T-cell subsets indicates that the Vδ2 γδ T cells might be skewed toward an activated and terminally differentiated effector memory phenotype by HIV infection, subsequently resulting in the dysfunction of Vδ2 γδ T cells. This finding is not consistent with the conclusion of Boudová et al.41 that showed that the proportion of TEM Vδ2 T cells was significantly decreased in HAART-treated groups. Given the heterogeneity of the patients assessed in this study, this discrepancy may be ascribed to differences in HIV strain, gender, transmission route and/or disease status.

Chronic immune activation is one of the well-known characteristics of HIV infection and AIDS pathogenesis.42,43 Vδ2 T cells are believed to be highly susceptible to activation-induced cell death.44 In the present study, we found that the expression levels of activation marker CD38 in memory Vδ2 γδ T cells were significantly elevated in all HIV-infected patients. Both TCM and TEM Vδ2 γδ T cells negatively correlated with CD38+γδ T cells. Conversely, TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells positively correlated with CD38+γδ T cells. These data indicate that immune activation accounts for the loss of memory TCM Vδ2 γδ T cells and an increase in the dysfunctional phenotype of TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients.

Intestinal microbial translocation is believed to contribute to chronic immune activation in HIV disease.27,31,33 Our study results show that microbial translocation marker sCD14 was significantly elevated in the plasma from HIV-infected patients, consistent with previous studies.45,46 Moreover, sCD14 showed significant correlation with HLA-DR+ γδ T cells. These findings suggest microbial translocation may partly contribute to the activation of γδ T cells.

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that IL-17-producing γδ T cells play crucial roles in inflammatory responses against infectious microorganisms.47,48 In this study, we found an increase in IL-17 producing γδ T cells in HIV-infected patients, particularly in fast progressors. Our results suggest that IL-17 producing γδ T cells may participate in HIV pathogenesis. Further, we observed a positive correlation between IL-17 producing γδ T cells and HLA-DR+ or CD38+HLA-DR+γδ T cells. This indicates that the IL-17 signaling pathway may be involved in γδ T-cell activation in HIV disease. Further studies on the activation of the IL-17 signaling pathway are needed for a better understanding of the mechanisms of chronic T-cell activation and HIV pathogenesis.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate a dynamic change in memory Vδ2 γδ T cells toward an activated and terminally differentiated effector phenotype TEMRA Vδ2 γδ T cell, which may account for the dysfunction of Vδ2 γδ T cells in HIV disease. The suggestive role of the IL-17 signaling pathway in T-cell activation in this study provides a new clue for further investigations into the mechanisms of chronic immune activation and HIV pathogenesis during HIV infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Mega-Projects of National Science Research for the 12th Five-Year Plan (2012ZX10001006), the Natural Science Foundation of China (30930083), the Ministry of Health (201302018) and the PUMC Scholarship for Dr Jianmin Zhang. We thank Dr Austin Cape for careful reading and comments.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- 1Hayday AC. Gammadelta T cells and the lymphoid stress–surveillance response. Immunity 2009; 31: 184–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Poccia F, Agrati C, Ippolito G, Colizzi V, Malkovsky M. Natural T cell immunity to intracellular pathogens and nonpeptidic immunoregulatory drugs. Curr Mol Med 2001; 1: 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Bonneville M, O'Brien RL, Born WK. Gammadelta T cell effector functions: a blend of innate programming and acquired plasticity. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10: 467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Schild H, Mavaddat N, Litzenberger C, Ehrich EW, Davis MM, Bluestone JA et al. The nature of major histocompatibility complex recognition by gamma delta T cells. Cell 1994; 76: 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Kong Y, Cao W, Xi X, Ma C, Cui L, He W. The NKG2D ligand ULBP4 binds to TCRgamma9/delta2 and induces cytotoxicity to tumor cells through both TCRgammadelta and NKG2D. Blood 2009; 114: 310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Qi J, Zhang J, Zhang S, Cui L, He W. Immobilized MICA could expand human Vdelta1 gammadelta T cells in vitro that displayed major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related A-dependent cytotoxicity to human epithelial carcinomas. Scand J Immunol 2003; 58: 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Brenner MB. Human gamma delta T cells recognize alkylamines derived from microbes, edible plants, and tea: implications for innate immunity. Immunity 1999; 11: 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Tanaka Y, Morita CT, Tanaka Y, Nieves E, Brenner MB, Bloom BR. Natural and synthetic non-peptide antigens recognized by human gamma delta T cells. Nature 1995; 375: 155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Constant P, Davodeau F, Peyrat MA, Poquet Y, Puzo G, Bonneville M et al. Stimulation of human gamma delta T cells by nonpeptidic mycobacterial ligands. Science 1994; 264: 267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10De Paoli P, Gennari D, Martelli P, Basaglia G, Crovatto M, Battistin S et al. A subset of gamma delta lymphocytes is increased during HIV-1 infection. Clin Exp Immunol 1991; 83: 187–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Autran B, Triebel F, Katlama C, Rozenbaum W, Hercend T, Debre P. T cell receptor gamma/delta+ lymphocyte subsets during HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol 1989; 75: 206–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Zheng NN, McElrath MJ, Sow PS, Mesher A, Hawes SE, Stern J et al. Association between peripheral gammadelta T-cell profile and disease progression in individuals infected with HIV-1 or HIV-2 in West Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 57: 92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Poccia F, Boullier S, Lecoeur H, Cochet M, Poquet Y, Colizzi V et al. Peripheral V gamma 9/V delta 2 T cell deletion and anergy to nonpeptidic mycobacterial antigens in asymptomatic HIV-1-infected persons. J Immunol 1996; 157: 449–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Li H, Peng H, Ma P, Ruan Y, Su B, Ding X et al. Association between Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells and disease progression after infection with closely related strains of HIV in China. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46: 1466–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Enders PJ, Yin C, Martini F, Evans PS, Propp N, Poccia F et al. HIV-mediated gammadelta T cell depletion is specific for Vgamma2+ cells expressing the Jgamma1.2 segment. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2003; 19: 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Li H, Chaudhry S, Poonia B, Shao Y, Pauza CD. Depletion and dysfunction of Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells in HIV disease: mechanisms, impacts and therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Immunol 2013; 10: 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Jansen CA, de Cuyper IM, Steingrover R, Jurriaans S, Sankatsing SU, Prins JM et al. Analysis of the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy during acute HIV-1 infection on HIV-specific CD4 T cell functions. AIDS 2005; 19: 1145–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Harari A, Petitpierre S, Vallelian F, Pantaleo G. Skewed representation of functionally distinct populations of virus-specific CD4 T cells in HIV-1-infected subjects with progressive disease: changes after antiretroviral therapy. Blood 2004; 103: 966–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Champagne P, Ogg GS, King AS, Knabenhans C, Ellefsen K, Nobile M et al. Skewed maturation of memory HIV-specific CD8 T lymphocytes. Nature 2001; 410: 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Huang X, Lodi S, Fox Z, Li W, Phillips A, Porter K et al. Rate of CD4 decline and HIV-RNA change following HIV seroconversion in men who have sex with men: a comparison between the Beijing PRIMO and CASCADE cohorts. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 62: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Huang X, Chen H, Li W, Li H, Jin X, Perelson AS et al. Precise determination of time to reach viral load set point after acute HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 61: 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Hubert JB, Burgard M, Dussaix E, Tamalet C, Deveau C, Le Chenadec J et al. Natural history of serum HIV-1 RNA levels in 330 patients with a known date of infection. The SEROCO Study Group. AIDS 2000; 14: 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Mahnke YD, Song K, Sauer MM, Nason MC, Giret MT, Carvalho KI et al. Early immunologic and virologic predictors of clinical HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS 2013; 27: 697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Zhou J, Kang N, Cui L, Ba D, He W. Anti-gammadelta TCR antibody-expanded gammadelta T cells: a better choice for the adoptive immunotherapy of lymphoid malignancies. Cell Mol Immunol 2012; 9: 34–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Kang N, Zhou J, Zhang T, Wang L, Lu F, Cui Y et al. Adoptive immunotherapy of lung cancer with immobilized anti-TCRgammadelta antibody-expanded human gammadelta T-cells in peripheral blood. Cancer Biol Ther 2009; 8: 1540–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Baroncelli S, Galluzzo CM, Pirillo MF, Mancini MG, Weimer LE, Andreotti M et al. Microbial translocation is associated with residual viral replication in HAART-treated HIV+ subjects with <50 copies/ml HIV-1 RNA. J Clin Virol 2009; 46: 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med 2006; 12: 1365–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Hazenberg MD, Stuart JW, Otto SA, Borleffs JC, Boucher CA, de Boer RJ et al. T-cell division in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infection is mainly due to immune activation: a longitudinal analysis in patients before and during highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Blood 2000; 95: 249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Hazenberg MD, Otto SA, van Benthem BH, Roos MT, Coutinho RA, Lange JM et al. Persistent immune activation in HIV-1 infection is associated with progression to AIDS. AIDS 2003; 17: 1881–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Rajasuriar R, Khoury G, Kamarulzaman A, French MA, Cameron PU, LewinSR. Persistent immune activation in chronic HIV infection: do any interventions work? AIDS 2013; 27: 1199–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Klatt NR, Funderburg NT, Brenchley JM. Microbial translocation, immune activation, and HIV disease. Trends Microbiol 2013; 21: 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Wallet MA, Rodriguez CA, Yin L, Saporta S, Chinratanapisit S, Hou W et al. Microbial translocation induces persistent macrophage activation unrelated to HIV-1 levels or T-cell activation following therapy. AIDS 2010; 24: 1281–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Cassol E, Malfeld S, Mahasha P, van der Merwe S, Cassol S, Seebregts C et al. Persistent microbial translocation and immune activation in HIV-1-infected South Africans receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2010; 202: 723–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Brenchley JM, Price DA, Douek DC. HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nat Immunol 2006; 7: 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Schulz SM, Kohler G, Holscher C, Iwakura Y, Alber G. IL-17A is produced by Th17, gammadelta T cells and other CD4- lymphocytes during infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis and has a mild effect in bacterial clearance. Int Immunol 2008; 20: 1129–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Nakayama K, Nakamura H, Koga M, Koibuchi T, Fujii T, Miura T et al. Imbalanced production of cytokines by T cells associates with the activation/exhaustion status of memory T cells in chronic HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012; 28: 702–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Hebbeler AM, Propp N, Cairo C, Li H, Cummings JS, Jacobson LP et al. Failure to restore the Vgamma2-Jgamma1.2 repertoire in HIV-infected men receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Clin Immunol 2008; 128: 349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Chaudhry S, Cairo C, Venturi V, Pauza CD. The gammadelta T-cell receptor repertoire is reconstituted in HIV patients after prolonged antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2013; 27: 1557–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Li H, Pauza CD. Critical roles for Akt kinase in controlling HIV envelope-mediated depletion of CD4 T cells. Retrovirology 2013; 10: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Herbeuval JP, Grivel JC, Boasso A, Hardy AW, Chougnet C, Dolan MJ et al. CD4+ T-cell death induced by infectious and noninfectious HIV-1: role of type 1 interferon-dependent, TRAIL/DR5-mediated apoptosis. Blood 2005; 106: 3524–3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Boudova S, Li H, Sajadi MM, Redfield RR, Pauza CD. Impact of persistent HIV replication on CD4 negative Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells. J Infect Dis 2012; 205: 1448–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42Miedema F, Hazenberg MD, Tesselaar K, van Baarle D, de Boer RJ, Borghans JA. Immune activation and collateral damage in AIDS pathogenesis. Front Immunol 2013; 4: 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Sodora DL, Silvestri G. Immune activation and AIDS pathogenesis. AIDS 2008; 22: 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Ferrarini M, Delfanti F, Gianolini M, Rizzi C, Alfano M, Lazzarin A et al. NF-kappa B modulates sensitivity to apoptosis, proinflammatory and migratory potential in short- versus long-term cultured human gamma delta lymphocytes. J Immunol 2008; 181: 5857–5864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Sandler NG, Wand H, Roque A, Law M, Nason MC, Nixon DE et al. Plasma levels of soluble CD14 independently predict mortality in HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2011; 203: 780–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46Ipp H, Zemlin AE, Glashoff RH, van Wyk J, Vanker N, Reid T et al. Serum adenosine deaminase and total immunoglobulin G correlate with markers of immune activation and inversely with CD4 counts in asymptomatic, treatment-naive HIV infection. J Clin Immunol 2013; 33: 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Hamada S, Umemura M, Shiono T, Tanaka K, Yahagi A, Begum MD et al. IL-17A produced by gammadelta T cells plays a critical role in innate immunity against listeria monocytogenes infection in the liver. J Immunol 2008; 181: 3456–3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48Chen M, Hu P, Peng H, Zeng W, Shi X, Lei Y et al. Enhanced peripheral gammadeltaT cells cytotoxicity potential in patients with HBV-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure might contribute to the disease progression. J Clin Immunol 2012; 32: 877–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]