Abstract

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a specialized subpopulation of T cells that control the immune response and thereby maintain immune system homeostasis and tolerance to self-antigens. Many subsets of CD4+ Tregs have been identified, including Foxp3+, Tr1, Th3, and Foxp3neg iT(R)35 cells. In this study, we identified a new subset of CD4+VEGFR1high Tregs that have immunosuppressive capacity. CD4+VEGFR1high T cells, which constitute approximately 1.0% of CD4+ T cells, are hyporesponsive to T-cell antigen receptor stimulation. Surface marker and FoxP3 expression analysis revealed that CD4+VEGFR1high T cells are distinct from known Tregs. CD4+VEGFR1high T cells suppressed the proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cell as efficiently as CD4+CD25high natural Tregs in a contact-independent manner. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells from wild type to RAG-2-deficient C57BL/6 mice inhibited effector T-cell-mediated inflammatory bowel disease. Thus, we report CD4+ VEGFR1high T cells as a novel subset of Tregs that regulate the inflammatory response in the intestinal tract.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, regulatory T cells, suppression, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1

Introduction

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play critical roles in the maintenance of immune homeostasis and prevention of autoimmunity and inflammation.1 Tregs were initially described by Gershon and Kondo in the early 1970s and were called suppressive T cells.2,3 In 1995, Sakaguchi et al. demonstrated that the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor α-chain, CD25, served as a phenotypic marker for CD4+ suppressor T cells or CD4+ Tregs and that these CD25+CD4+ T cells prevented the development of autoimmune diseases.4

Since then, many phenotypically distinct CD4+ Treg subsets have been identified, including Foxp3+, IL-10-secreting Tr1, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-secreting Th3, and Foxp3negiT(R)35 cells.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 The mechanisms of Treg function generally include the following: suppression by inhibitory cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), TGF-β, and IL-35; suppression of effector T cells by IL-2 depletion or generation of pericellular adenosine; suppression by targeting dendritic cells (DCs) through cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen (CTLA), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and lymphocyte-activation gene 3; and cytolysis by secretion of granzyme-A and -B.15,16

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR1) has seven immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains in the extracellular domain (ECD), a single transmembrane region and a consensus tyrosine kinase sequence. VEGFR1 binds VEGFA, VEGFB, and placental growth factor (PlGF). VEGFR1 was initially reported to act as a decoy receptor and modulates angiogenesis through its ability to sequester VEGFA because of its weak tyrosine kinase activity and a high affinity for VEGFA.17,18 Recently, VEGFR1 was shown to mobilize bone marrow-derived cells via its tyrosine kinase activity19 as well as induce monocyte migration and chemotaxis.20,21 Kaplan et al. demonstrated that VEGFR1+ hematopoietic bone marrow progenitors home to tumor-specific pre-metastatic sites and dictate organ-specific tumor spread.22 Dikov et al. reported that VEGFR1 is the primary mediator of VEGF-mediated inhibition of DC maturation.23 In the case of T cells, the engagement of T-cell VEGFR1 with its ligand induces IL-10 production and chemotaxis toward VEGF.24

However, the function of VEGFR1-expressing CD4+ T cells has not been identified. Our previous work prompted us to investigate whether a subset of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells contains suppressive capacity similar to that of Tregs. In this study, we show that CD4+VEGFR1high T cells exist in the lymph node, spleen, and thymus, and they are phenotypically distinct from other known Tregs. Importantly, CD4+VEGFR1high T cells can suppress T-cell proliferation via soluble factor-mediated apoptosis and lead to suppression of effector T-cell-mediated inflammatory colitis, as shown by adoptive transfer into RAG-2-deficient mice. In summary, we report CD4+VEGFR1high T cells as a distinct subset of Tregs that regulate the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Materials and methods

Mice

GFP-Foxp3 knock-in mice on a C57BL/6 background were generously provided by Prof. Seong-Hoe Park (Seoul National University college of Medicine) with the permission of Prof. A. Rudensky (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center). Thy1.1-B6 and RAG-2 knock-out (KO) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. OT-II mice were provided by Prof. Dong Sup Lee (Seoul National University College of Medicine). C57BL/6 mice at 7–12 weeks of age were purchased from Central Laboratory Animal, Inc. and maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions, according to the guidelines of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources of Seoul National University. All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Seoul National University.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions of thymi, lymph nodes (inguinal, axial), and spleens from 7- to 10-week-old mice were washed and resuspended in 100 μL of cold staining buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% sodium azide in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Before staining, each sample was blocked with anti-FcR monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (2.4G2, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) for 10 min at room temperature (RT). The following antibodies (Abs) were used: FITC- or PE-labeled anti-CD8a, APC-Cy7-labeled anti-CD25, PerCP or PE-labeled anti-CD3, FITC-labeled anti-CD103, PE-labeled anti-CTLA4 (for cell surface), and the respective isotype control Abs (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). APC-labeled or purified anti-mouse VEGFR1 Abs were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). FITC- or PE-Cy7 labeled anti-CD4, FITC-labeled anti-GITR, and the respective isotype control Abs were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Alexa Fluor 647-labeled anti-rat IgG was from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR, USA). The cells were incubated for 30 min on ice in 100 μL of staining buffer containing the appropriate concentration of Ab. At the end of the staining, the pellets were washed with staining buffer and analyzed using a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva and FlowJo software. For detection of intracellular (IC) cytokine production, the cultured CD4+ T cells were restimulated with 50 ng mL−1 phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) plus 500 ng mL−1 ionomycin plus Brefeldin A (10 μg mL−1) for 5 h. The cells were stained with APC-labeled anti-mouse interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and PE-labeled anti-mouse IL-17A (BD Biosciences) using IC fixation buffer and 10× permeabilization buffer (eBioscience). IC staining of Foxp3 was conducted using FITC-labeled anti-mouse Foxp3 (FJK-16s), Fixation/Permeabilization Concentrate & Diluent set and 10× permeabilization buffer (eBioscience), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Isolation of splenic CD4+ T cells and cell sorting

CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleens of mice by positive or negative selection using the MACS magnetic separation system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, spleen cell suspensions were incubated in cold protein extraction buffer (PEB) (PBS supplemented with 2 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 0.5% BSA) with magnetic microbeads conjugated to anti-CD90.2, anti-mouse CD4, or biotin-Ab cocktail/anti-biotin microbeads (CD4+ T-cell isolation kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were washed twice and loaded onto the magnetic separation columns. Flow cytometry was performed using anti-mouse CD3 or anti-mouse CD4 Abs (eBioscience), and populations were confirmed to be ≥85% CD3+ or CD4+ T lymphocytes. Purified CD4+ T cells were sorted into CD4+Foxp3/GFP+, CD4+Foxp3/GFP−, CD4+Foxp3/GFP+VEGFR1negative, CD4+Foxp3/GFP−VEGFR1high, CD4+CD25high, CD4+CD25−, CD4+VEGFR1high, and CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells using a JSAN Cell Sorter (Bay Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan). CD4+VEGFR1−CD25−, CD4+VEGFR1+CD25−, and CD4+CD25− T cells were sorted by a BD-FACS Aria I cell sorter (BD Biosciences) for in vivo experiments. After sorting, the cells were routinely ≥90% viable, as assessed by trypan blue exclusion.

T-cell activation and in vitro suppression assay

Freshly sorted CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated with 3 μg mL−1 or 5 μg mL−1 soluble anti-CD3 mAb in the presence of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in a U-bottomed 96-well plate for three or four days and then pulsed with 1 μCi/well [3H] thymidine for 18 h. Tregs were added to the culture at the indicated doses. The APCs used were irradiated (2000 rad) mouse splenocytes. The cells were cultured in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2-mercaptoethanol (ME), l-glutamine, gentamicin, essential and nonessential amino acids, and HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich) for the indicated time in a CO2 incubator. The cultured cells were harvested, and the incorporated [3H] thymidine (Amersham Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) was measured as counts per minute with a beta counter. For some experiments, CD4+CD25− T cells were labeled with 5 μM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) before the suppression assay, and the level of proliferation was assessed by determining the dilution of CFSE using flow cytometry after the initiation of the cultures. For in vitro antigen-mediated suppression assay, CD4+CD25− T cells from the spleens of OT-II T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) transgenic mice were used as responders and were stimulated with 1.0 μM ovalbumin (OVA) peptide-pulsed APCs in the absence or presence of Tregs. The cultures were maintained at 37 °C for three or four days and pulsed with 1 μCi/well [3H] thymidine for 18 h. For blocking assay, 10 μg mL−1 neutralizing anti-VEGFR1 Ab (R&D systems) was added to standard suppression assay.

Transwell experiments were performed in 96-well plates with a pore size of 1.0 μm (Corning Incorporated, Lowell, MA, USA). CD4+CD25− T cells plus APCs in the lower chamber and CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells plus APCs in the upper or lower chamber were stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb in 96-well transwell culture plates. Additionally, incorporation of [3H] thymidine by proliferating cells during the last 18 h of the culture was measured. For preparation of culture supernatants (CSs) from CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells, cells were cultured under stimulation with 10 μg mL−1 plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb and 1 μg mL−1 soluble anti-CD28 mAb in the presence or absence of 100 U mL−1 IL-2 for three days. Non-conditioned media were prepared with CS from CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells incubated for three days without any stimulators. The CS was harvested and kept frozen at −80 °C until use.

Flow cytometric measurement of apoptosis

To assay for apoptosis, cells were harvested, washed with cold PEB, and resuspended in 100 μL of Annexin V staining buffer. PE-Annexin V and 7AAD (BD Biosciences) were added and incubated for 15 min at RT in the dark. After staining, 400 μL of binding buffer was added to each sample. The results were analyzed by flow cytometry. To determine the mechanism of apoptosis induction, we investigated B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) expression (intrinsic pathway) and caspase-8 activity (extrinsic pathway). For IC detection of Bcl-2, the cells were harvested, washed in cold PEB, fixed with 100 μL of IC fixation buffer (eBioscience), and incubated in the dark at RT for 20 min. After fixation, the cells were washed with permeabilization buffer (eBioscience), stained with FITC-labeled anti-Bcl-2 (eBioscience), incubated in the dark at RT for 20 min, washed with permeabilization buffer, and analyzed by flow cytometry. IC caspase-8 detection was performed using the caspase-8 apoptosis detection kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cells were harvested and washed with PBS, and reaction mixtures were prepared by combining 100 μL of cell suspension, 400 μL of PBS, and 10 μL of N-Acetyl-Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp-7-amino-4-(trifluoromethyl)-coumarin (IETD-AFC) substrate. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, and free AFC was measured by flow cytometry. The results are presented as the amount of AFC from apoptotic cells to that of non-apoptotic cells.

Adoptive T-cell transfer to RAG2 KO mice and cell preparations

CD4+VEGFR1+CD25−, CD4+VEGFR1−CD25−, or CD4+CD25+ T cells were sorted using a BD-FACS Aria I cell sorter (BD Biosciences) and intravenously transferred into seven-week-old RAG2 KO mice. After seven weeks, the recipient mice were sacrificed, and their colon tissues were extracted for histopathological analysis of paraffin-embedded sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Additionally, the body weights of the recipient mice were monitored after T-cell transfer. For cell isolation from peripheral lymphoid organs, the spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN) were mechanically disrupted into single cell suspensions. To assess for colonic lamina propria lymphocytes (LPL), the colons were isolated and flushed extensively to eliminate the lumen content. The colons were cut into small pieces and incubated in Ca- and Mg-free PBS-ontaining 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5 mM EDTA, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 30 min at RT to release intraepithelial lymphocytes. The samples were then resuspended in DMEM with 5% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U mL−1 collagenase IV (Invitrogen) and 100 μg mL−1 DNase I (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and shaken at 37 °C for 90 min. The supernatants and colons were collected and passed through a 40-μm strainer and washed. The cells were centrifuged in a Ficoll gradient (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) at 600g for 40 min. The lymphocytes were collected from the lymphocyte layer, washed, and used for further experiments.

Statistical analysis

The values for all measurements are presented as the mean ± SEM. Analysis of variance was used to compare the differences between groups. Comparisons for all pairs were performed by Student's t-test. A p-value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Phenotypic analysis of CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells

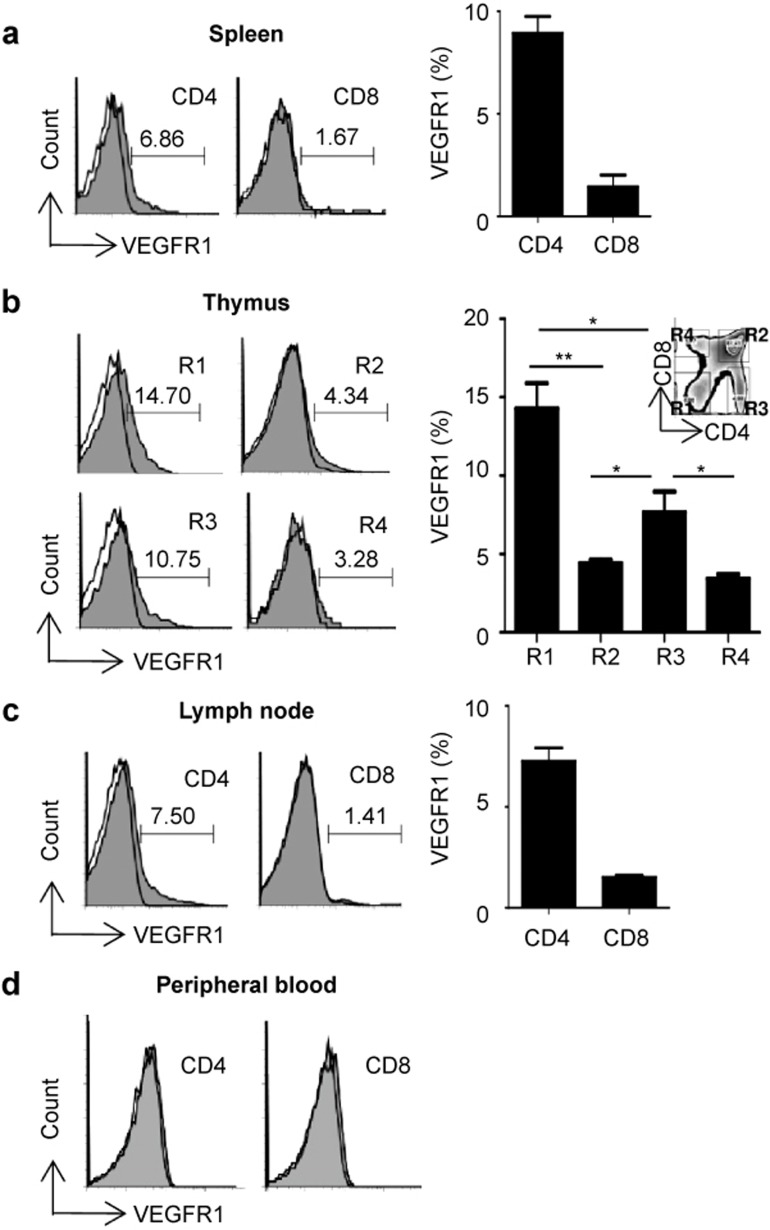

We previously reported that VEGFR1 is expressed on T cells.24 In that study, goat anti-mouse VEGFR1 polyclonal Ab was used to stain the VEGFR1 on T cells as the mAb was not available at that time. Recently, rat anti-mouse VEGFR1 mAb has been developed and become available. In this study, we reconfirmed the expression of VEGFR1 on T cells by the mAb and found the frequency of VEGFR1+ T cell was different from that assessed by polyclonal Ab. Approximately 7–15% of CD4+ and 2–5% of CD8+ T cells in the spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes expressed VEGFR1 and about 1% of CD4 and CD8 T cells were positive for VEGFR1 in peripheral blood (Figure 1). Interestingly, the frequency of VEGFR1+ cells was higher in double negative (DN, 14%) than in double positive (DP, 5%) thymocytes (histograms shown in Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

T-cell VEGFR1 expression. Cell suspensions of (a) spleens, (b) thymus, (c) lymph nodes (LNs), and (d) peripheral blood from C57BL/6 mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. The proportions of VEGFR1+ on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from (a) spleens, (b) thymi, and (c) LNs in the right panel are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. The expression level of VEGFR1 in the thymus was analyzed in different quadrants following the differentiation of thymocytes: R1, CD4−3CD8−3 (double negative, DN); R2, CD4+CD8+ (double positive, DP); R3, CD4+CD8−3 (single positive, SP); R4, CD4−3CD8+ (single positive, SP). The solid histograms represent the isotype controls and the tinted histograms show the distribution of positive cells, gated for CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, as indicated. Results from one representative experiment out of three are shown.

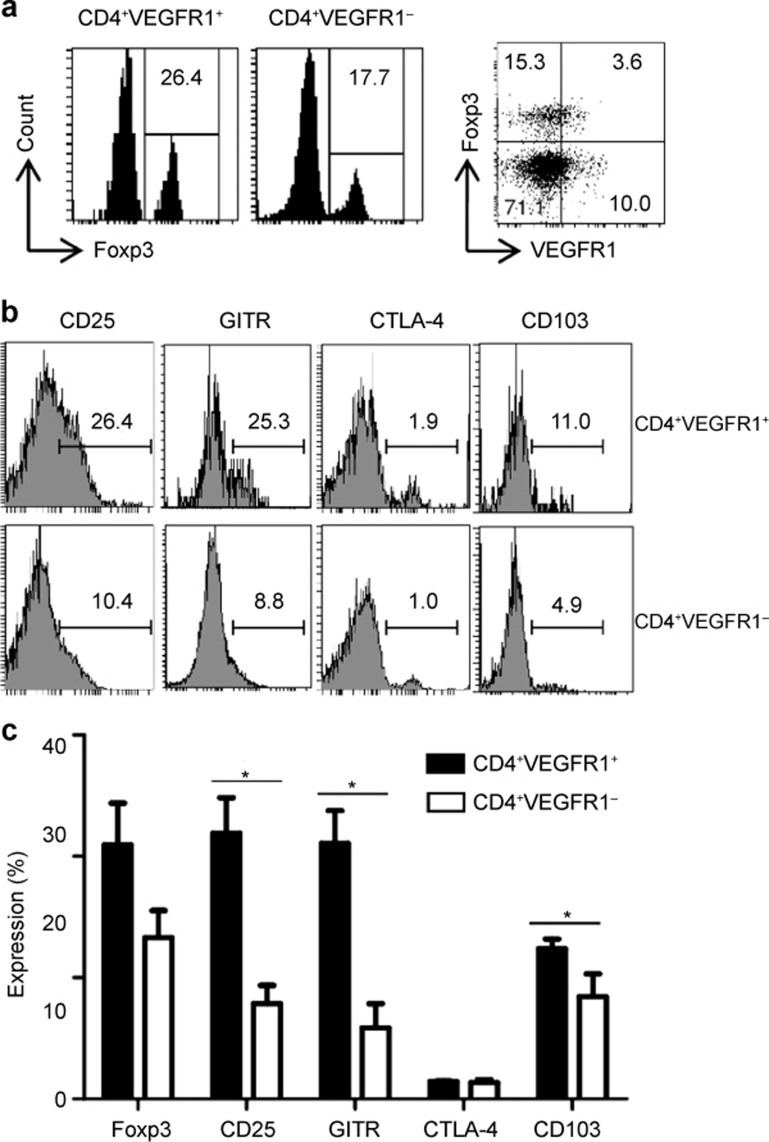

For the phenotypic analysis of CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells, we assessed the expression of Foxp3, CD25, glucocorticoid-inducible tumor necrosis factor receptor (GITR), CTLA-4, and CD103 in CD4+VEGFR1+ and CD4+VEGFR1− T cells. These are specific markers of Tregs.4,6,25,26 The number of cells expressing CD25, GITR, and CD103 in the CD4+VEGFR1+ T-cell populations was found to be approximately 2- to 3-fold higher than that in the CD4+VEGFR1− T-cell population (Figure 2b and 2c). Considering that the number of Foxp3+ T cells in CD4+VEGFR1+ T-cell population was not significantly different from that in CD4+VEGFR1− T-cell populations (Figure 2), the plausible bias by the contained Foxp3+ T cells in the expression of CD25, GITR, and CD103 on CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells would be negligible. In addition, although expression level of CD25, GITR, and CD103 in CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells was significantly higher than in CD4+VEGFR1− T cells, they did not coincide with the level observed in CD4+Foxp3+ T cells. It has been reported that Foxp3 was found to be expressed on over 80% of CD4+CD25+ T cells but was almost undetectable on CD4+CD25− T cells. In addition, the molecules GITR, CTLA4, and CD103 have been reported to be expressed on approximately 80%, 20–30%, and 20–30% of CD4+CD25+ Tregs compared with approximately 6%, 1%, and 1% of CD4+CD25− T cells, respectively.25,26,27 These results indicated that CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells are phenotypically distinct from other known Treg.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic characterization of CD4+VEGFR1+ and CD4+VEGFR1−3 T cells. CD4+ T-cell VEGFR1 and Foxp3 expression from C57BL/6 mice is shown in (a) (right dot plots). (a and b) Expression levels of Foxp3, CD25, GITR, CTLA-4, and CD103 for CD4+VEGFR1+ and CD4+VEGFR1−3 populations are shown from one representative experiment out of three. (c) The proportions of cells positive for Foxp3, CD25, GITR, CTLA-4, and CD103 within the CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells and CD4+VEGFR1−3 T-cell populations are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (Student's t-test, *p <0.05).

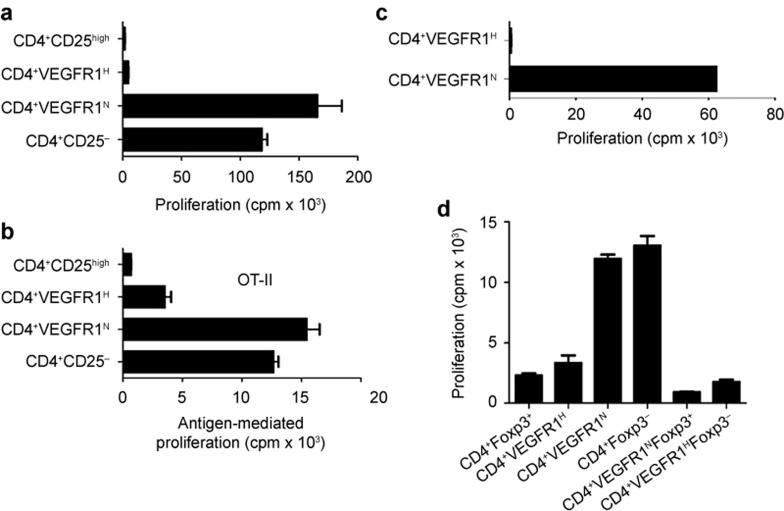

CD4+VEGFR1high T cells are hyporesponsive to TCR stimulation and suppress proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells regardless of Foxp3 in vitro

We isolated these cells by sorting for VEGFR1 and CD4 expression. To ensure complete separation, the upper about 1.0% of VEGFR1+ cells were collected as CD4+VEGFR1high T cells, and the lower less than 10.0% of CD4+VEGFR1− T cells were collected as CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells. For suppression assays, CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells were co-cultured with CD4+CD25− T cells that were stimulated by anti-CD3 and APCs for four days. CD4+CD25high T cells were used as a positive control for Tregs. As shown in Figure 3a, CD4+VEGFR1high T cells significantly inhibited the proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells to the same degree as the CD4+CD25high Tregs. In contrast, no inhibition was observed with CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells. Furthermore, we investigated whether CD4+VEGFR1high T cells can suppress the CD4+CD25− T-cell proliferation by antigen-laden APCs. Although OT-II TCR transgenic mice have low level of Tregs,28 CD4+VEGFR1high, CD4+VEGFR1negative, and CD4+CD25high T cells were purified from the spleens of OT-II TCR transgenic mice and co-cultured with TCR transgenic CD4+CD25− T cells stimulated with OVA (OT-II) peptide-pulsed APCs. We confirmed that suppressive capacity between CD4+VEGFR1high and CD4+CD25high T cells has no significant difference (Figure 3b). Next, we assessed the proliferative capacity of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells. Stimulation by anti-CD3 and APCs failed to induce proliferation of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells, as shown in Figure 3c, indicating that CD4+VEGFR1high T cells are anergic, consistent with one of the characteristics of Tregs. To exclude the possible contribution of Foxp3, CD4+VEGFR1highFoxp3− T cells were isolated from the spleens of Foxp3-GFP knock-in mice. The purified CD4+VEGFR1highFoxp3− T cells were co-cultured with CD4+CD25− T cells stimulated by anti-CD3 and APCs. Of note, we found that CD4+VEGFR1highFoxp3− T cells significantly suppressed the proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells as efficiently as CD4+VEGFR1−Foxp3+ or CD4+Foxp3+ (Figure 3d). This result suggested that the suppressive capacity of CD4+VEGFR1high T cell is not dependent on Foxp3.

Figure 3.

CD4+VEGFR1high T cells are unresponsive to TCR stimulation and suppress proliferation of CD4+CD25−3 T cells regardless of Foxp3 in vitro. For suppression assay, CD4+VEGFR1negative and CD4+VEGFR1high T cells were sorted by a JSAN Cell Sorter. (a) CD4+CD25high, CD4+CD25−3, CD4+VEGFR1high, or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells were sorted by a JSAN Cell Sorter, and CD4+CD25−3 T cells (5 × 104) were cultured with CD4+CD25high, CD4+CD25−3, CD4+VEGFR1high, or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells (1 × 104) in the presence of anti-CD3 (5 μg mL−31) mAb and APCs (2.5 × 105). (b) CD4+CD25−3 T cells from OT-II TCR transgenic mice were stimulated with 1.0 μg mL−31 OVA323-339 peptide and APCs in the presence or absence of CD4+CD25high, CD4+VEGFR1high, or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells. (c) CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells (1 × 105) were stimulated with anti-CD3 and APCs (5 × 105). (d) CD4+Foxp3−3 T cells (5 × 104) from GFP-Foxp3 knock-in C57BL/6 mice were simulated with anti-CD3 and APCs in the presence or absence of CD4+Foxp3/GFP+, CD4+VEGFR1high, CD4+VEGFR1negative, CD4+Foxp3/GFP−3, CD4+VEGFR1negativeFoxp3/GFP+, or CD4+VEGFR1highFoxp3/GFP−3 T cells (1 × 104). The cultures were maintained at 37°C for four days and pulsed with 1 μCi/well [3H] thymidine for 18 h. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of triplicates from one representative out of two or three performed. R1H and R1N indicate R1high and R1negative, respectively.

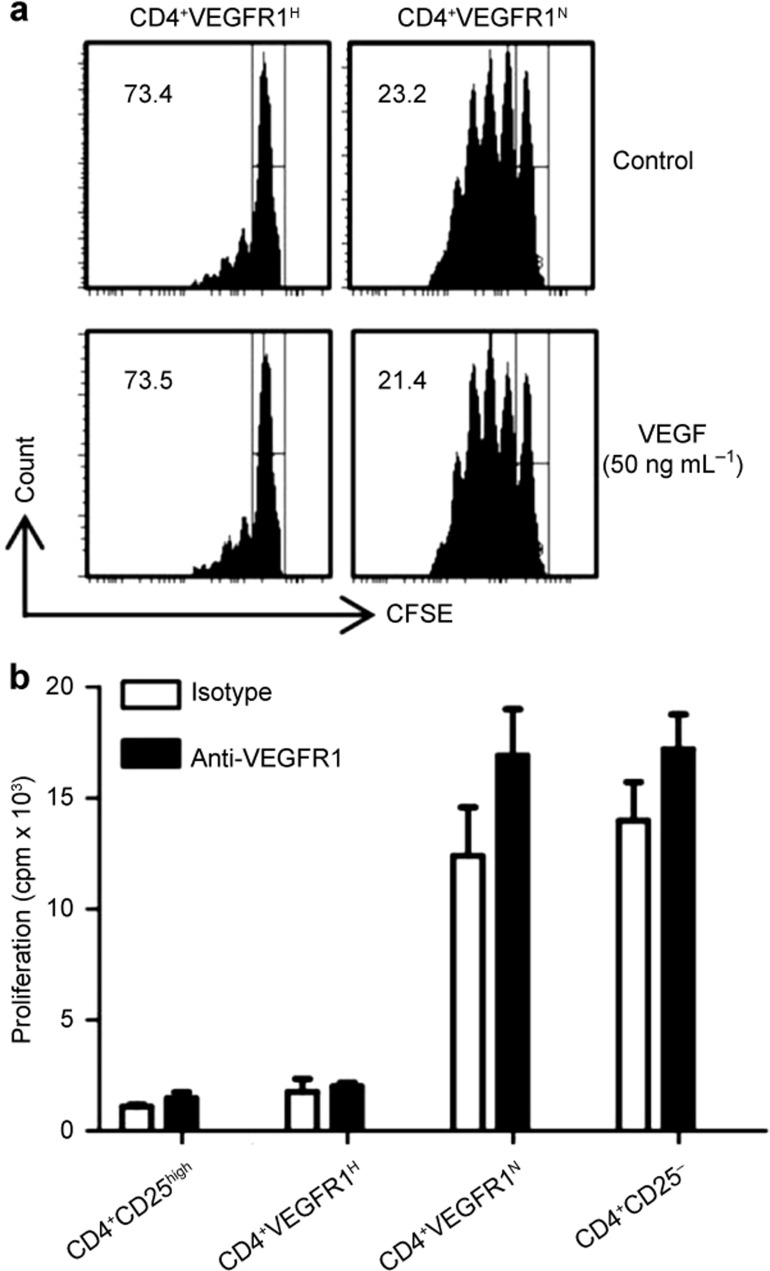

VEGF and anti-VEGFR1 mAb do not alter CD4+VEGFR1high Treg suppressor activity

To investigate whether signaling through VEGFR1 contributes to the suppression mediated by CD4+VEGFR1high T cells, we evaluated the suppressive capacity of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells in the presence of VEGF or neutralizing anti-VEGFR1 mAb. CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25− T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3, and APCs and were co-cultured with CD4+VEGFR1high T cells in the presence or absence of VEGF or anti-VEGFR1 mAb. CD4+VEGFR1high T cells suppressed the proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells irrespective of the presence of VEGF (Figure 4a) or anti-VEGFR1 mAb (Figure 4b), indicating that ligand binding of VEGFR1 does not influence the suppressive activity of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells. These results clearly showed that VEGFR1 signaling is not required for the CD4+VEGFR1high T-cell-mediated suppression.

Figure 4.

Effect of VEGF treatment and neutralization of VEGFR1 on CD4+VEGFR1high T-cell-mediated suppression. (a) CD4+CD25−3 T cells from the spleens of CD57BL/6 mice were labeled with 5 μM CFSE, and incubated with anti-CD3 and APCs and CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+ VEGFR1−3 T cells in the presence or absence of VEGF (50 ng mL−31). After three days of culture, CFSE fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry and shown from one representative experiment out of two performed. The percentage inhibition of proliferation is shown in each panel. (b) Neutralizing antibodies (10 μg mL−31 anti-VEGFR1 or isotype antibody) were added to the in vitro standard suppression assays, and the cells were then cultured for four days. The proliferative response was measured by analyzing [3H] thymidine incorporation in the harvested cells. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of triplicates from one representative experiment out of two performed.

Soluble mediator(s) are potentially involved in CD4+VEGFR1high T-cell-mediated suppression through apoptosis induction

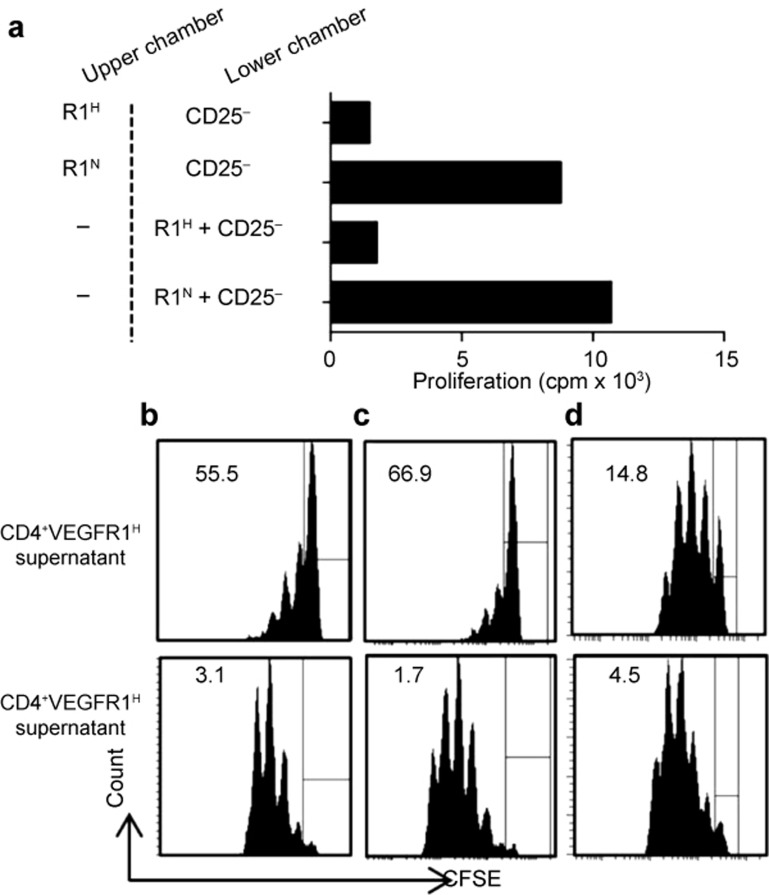

To determine whether cell-to-cell contact is required for CD4+VEGFR1high T-cell-mediated suppression, we performed transwell experiments. CD4+VEGFR1high T cells were placed in the upper chamber, and CD4+CD25− T cells were placed in the lower chamber. Cells in the both chambers were stimulated by anti-CD3 and APCs, and the proliferation of cells in the lower chamber was determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation. As shown in Figure 5a, CD4+VEGFR1high T cells suppressed the proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells in the absence of cell-to-cell contact, suggesting that the CS from CD4+VEGFR1high T cells contains a factor that mediates the suppressive activity. As another way, the CSs from CD4+VEGFR1high and CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells were prepared by stimulating cells with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the presence or absence of IL-2. CD4+CD25− T cells were labeled with 5 μM CFSE and then stimulated with anti-CD3 and APCs in the presence of CS. As shown in Figure 5b and 5c, the CS from CD4+VEGFR1high T cells significantly inhibited the proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells regardless of adding IL-2. Interestingly, the CS from non-stimulated CD4+VEGFR1high T cells slightly suppressed CD4+CD25− T-cell proliferation (Figure 5d). These results indicated that most of the suppression of cell proliferation was mediated by soluble factor(s) derived from the activated state of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells.

Figure 5.

The suppressive activity of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells is mediated by soluble factor(s). (a) In transwell cultures, CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells (1 × 104) were cultured with anti-CD3 and APCs in the upper or lower chambers of transwell culture plates, as indicated. CD4+CD25−3 T cells (5 × 104) were cultured in the lower chambers of the 96-well plates in medium containing anti-CD3 and APCs. The cultures were maintained for a total of 96 h and pulsed with [3H] thymidine for 18 h. The proliferating cells in the lower chambers were determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation. (b–d) Supernatants from CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells were harvested from different culture conditions. CFSE-labeled (5 μM) CD4+CD25−3 T cells (1 × 105) were stimulated with anti-CD3 (3 μg mL−31) and APCs (1 × 106) and cultured in a medium containing 50% culture supernatants obtained from each culture condition. The supernatants were obtained from cultured CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells (1 × 105) with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 μg mL−31) and soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg mL−31) mAb in the absence (b) or presence (c) of IL-2 (100 U mL−31). (d) CD4+VEGFR1high or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells were cultured in the absence of stimulators for three days and then each collected supernatant was used as a control (non-conditioned media). Results are shown from one representative experiment out of two performed. Results are shown as mean ± SEM of triplicates from one representative experiment out of two performed. R1H and R1N indicate R1high and R1negative, respectively.

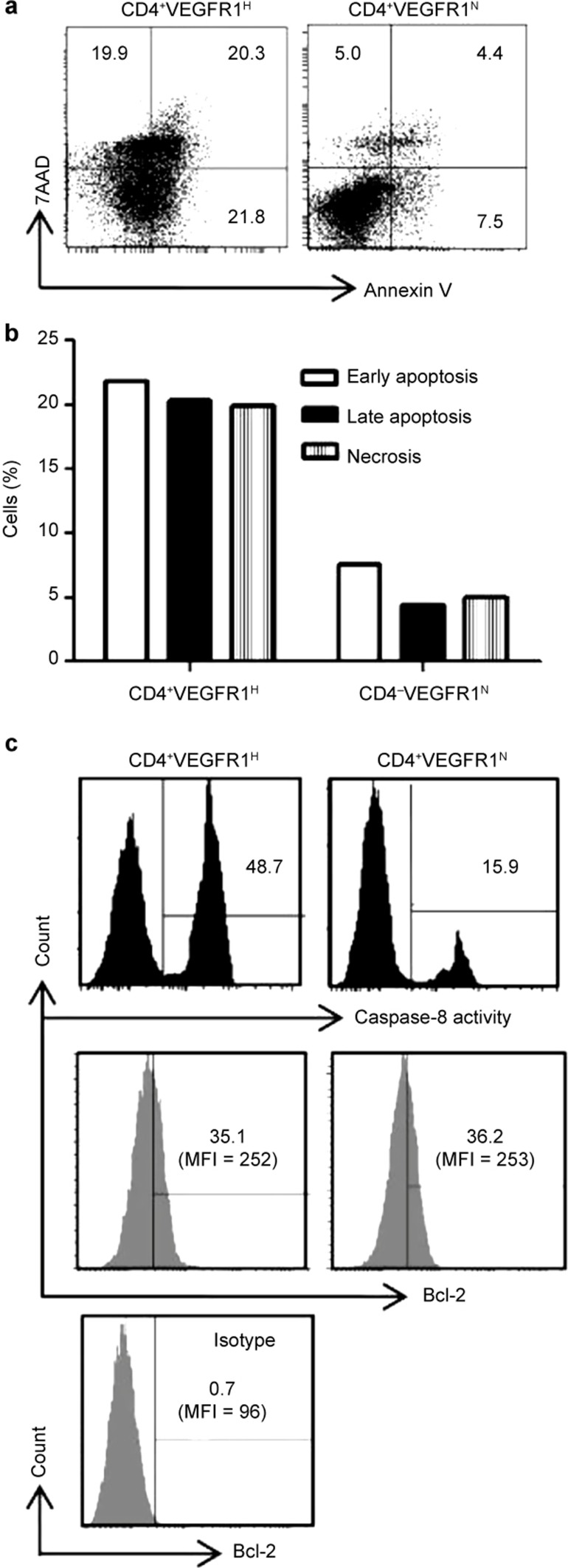

The suppression of cell proliferation and cell death (apoptosis) was determined by CFSE labeling and Annexin V/7AAD, respectively.29 We stained CD4+CD25− T cells activated by CS with Annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) on day 4 after stimulation and analyzed the cells by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 6a and 6b, the rate of CD4+CD25− T cells in all phases of apoptotic death significantly increased, including early apoptosis (Annexin V-positive cells only; Figure 6a, lower right quadrant), late apoptosis (both Annexin V- and 7AAD-positive cells; Figure 6a, upper right quadrant), and necrosis (7AAD-positive cells only; Figure 6a, upper left quadrant). We then assessed the degree of caspase-8 activation and the expression level of Bcl-2, which are known to be representative markers of apoptosis pathways, by Ab staining and subsequent flow cytometric analysis. As shown in Figure 6c, the activity of caspase-8 was significantly higher in the cells treated with CD4+VEGFR1high T-cell-derived CS; however, the expression level of Bcl-2 did not differ from the control. Collectively, these data suggest that the soluble mediator(s) from CD4+VEGFR1high T cells mediate the suppression of cell proliferation through the induction of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Figure 6.

Soluble factor(s) from CD4+VEGFR1high T cells induce apoptosis of CD4+CD25−3 T cells. Supernatants from activated CD4+VEGFR1high T cells or CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells cultured with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 and IL-2 for three days were added to CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25−3 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and APCs and cultured for four days. After incubation, the cells were harvested and stained with Annexin V (surface) and 7AAD (nuclear). CFSE-positive cells were analyzed for staining patterns of Annexin-V and 7AAD by flow cytometry. Control indicates non-conditioned media. (a) Dot plot and (b) graph are shown from one representative experiment out of three performed. (c) Bcl-2 expression and caspase-8 activity were detected in CD4+CD25−3 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and APCs for four days in the presence of either supernatant of activated CD4+VEGFR1high T cells or CD4+VEGFR1−3 T cells. The results are shown from one representative experiment out of two performed. R1H and R1N indicate R1high and R1negative, respectively.

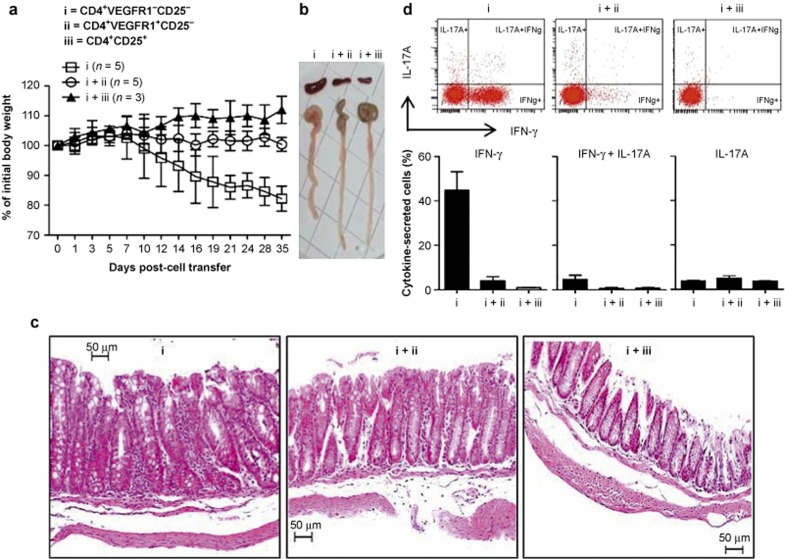

Adoptive transfer of CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells ameliorates IBD in lymphopenic mouse

We explored the role of CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells in vivo using mouse IBD models established in previous studies.30,31 RAG-2 KO mice were injected intravenously with CD4+VEGFR1+CD25−, CD4+VEGFR1−CD25−, or CD4+CD25+ T cells isolated from C57BL/6 mice. RAG2 KO mice injected with CD4+VEGFR1−CD25− T cells exhibited weight loss at seven or eight weeks after transfer (Figure 7a). Histology of the colon revealed the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lamina propria and submucosa with a thickened wall, which are findings indicative of colitis (Figure 7c). The mice that received CD4+VEGFR1−CD25− T cells with CD4+VEGFR1+CD25− T cells did not show any weight loss or detectable symptoms, and the colons showed normal histology, which was shown in mice received CD4+CD25+ T cells (Figure 7a and 7c). The spleens and colons of CD4+VEGFR1−CD25− T-cell-transferred RAG2 KO mice were markedly enlarged when compared with that of Treg-injected mice (Figure 7b). The CD4+ T cells in the lamina propria of the colon of the mice suffering from colitis were isolated and assayed for cytokine expression by IC cytokine staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. The percentages of IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells in only CD4+VEGFR1−CD25− T-cell-injected mice were 10-fold higher than in control mice, but the ratio of IL-17A-producing CD4+ cells did not differ between the group of mice with colitis and the control groups (Figure 7d). We additionally observed that CD4+VEGFR1−CD25− T-cell-injected mice have the same symptoms with CD4+CD25− T-cell-injected RAG-2 KO mice such as weight loss, enlarged spleens and colons, the infiltration of inflammatory cells, intestinal crypt destruction (data not shown). Taken together, the above results confirmed that CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells can play an essential role in vivo in the control of expansion of immune cells involved in Th1-mediated development of IBD.

Figure 7.

Transfer of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells into RAG2-KO mice. (a) CD4+VEGFR1−3CD25−3 (i), CD4+VEGFR1+CD25−, (ii) or CD4+CD25+ T cells (iii) (2 × 105) sorted from the spleens of C57BL/6 mice were injected into the tail veins of RAG2 KO mice. Each mixture of CD4+VEGFR1+CD25−3 or CD4+CD25+ T cells with CD4+VEGFR1−3CD25−3 T cells (1:1 ratio) was injected into RAG-2 KO mice. The group of RAG2 KO mice co-injected with CD4+VEGFR1−3CD25−3 and CD4+CD25+ T cells (1:1 ratio) was monitored as a control group. Body weight was monitored as indicated in Figure 6a and is presented as a percentage of initial weight at day 0: (body weight at the indicated days)/(body weight at day 0) ×100 ± SEM. (b) The representative size of spleens and colons from the indicated cells-injected RAG2 KO recipient mice. (c) Colonic tissues were collected seven weeks post-cell transfer, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and analyzed by microscopy (original magnifications: 200×). (d) Lamina propria lymphocytes from the colon were harvested seven weeks post-cell transfer and stimulated ex vivo, and IFN-γ and IL-17 expression from one representative experiment are shown as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that CD4+VEGFR1high T cells suppress the proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells by soluble factor(s)-mediated induction of apoptosis and ameliorate IBD induced in lymphopenic mice, confirming the important role of CD4+VEGFRhigh T cells in the maintenance of immune homeostasis.

VEGF and VEGFR have profound effects on both developmental hematopoiesis and pathologic conditions.32,33,34,35,36,37,38 We first investigated the expression level of VEGFR1 in the murine thymocytes and T cells. We observed DN, DP, and SP (CD4 and CD8) thymocytes expressed VEGFR1. We also observed VEGFR1 on the surface of CD4 and CD8 T cells isolated from spleen and LN, but could find very low levels of VEGFR1+ cells in T cells from peripheral blood. Of note, we observed the ratio of CD4 and CD8 splenic T cells expressing VEGFR1 varies depending on the nature of Ab (polyclonal vs. monoclonal) resulting in the higher ratio with polyclonal Ab.24 Considering that VEGFR1 is expressed on human CD34+ and mouse Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs),39 VEGFR1 may be expressed from the early phase of T-cell development, and perhaps these cells be derived from VEGFR1+ bone marrow HSCs. On the other hand, considering that the frequency of VEGFR1+ T cells in the peripheral blood is lower than in lymphoid organs, VEGFR1+ T cells might be induced in certain tissue microenvironment.40,41

In previous study, we reported that the engagement of VEGFR1 with VEGF did not affect the proliferation of T cells but induced T-cell migration.24 In mouse model of chronic infusion of VEGF, VEGFR2 signaling significantly inhibited thymic T-cell development and decreased total number of splenic T cells, whereas VEGFR1 signaling contributed to the mobilization of T cells such as T precursors from the bone marrow and T cells from thymus to spleen.38 Furthermore, the treatment of neutralizing anti-VEGFR1 Ab and exogenous VEGF did not affect the suppressive function of CD4+VEGFR1high T cell. However, VEGFR1 would be involved in the migration of these cells and cause cleavage of IL-2 receptor α (CD25) from the surface of activated T cells through the induction of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) under a certain environment such as VEGF or a ligand-enriched environment.24,42,43

Considering these factors that (i) the expression pattern of Foxp3 and several other surface markers in CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells are different from CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs, (ii) CD4+VEGFR1high T cells suppress T-cell proliferation without Foxp3, (iii) the suppressive capacity of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells is independent of cell-to-cell contact, CD4+VEGFR1high T cells would be a new distinct subtype of Tregs different from CD4+Foxp3+ natural Tregs.

What would be the mechanisms underlying the suppressive effect of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells? The CS from activated CD4+VEGFR1high T cells induced inhibition of T-cell proliferation and apoptotic death of activated T cells, indicating that soluble factor(s) should be involved in a suppressive mechanism of CD4+VEGFR1high T cell. To get insight into the mechanism that could be responsible for apoptosis induced by CS, we have investigated the impact of extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis into CS-induced CD4+CD25− T-cell death. Apoptosis can be triggered by the ligation of cell surface death receptors (extrinsic apoptosis pathways) or stress signals through the release of apoptogenic factors from mitochondrial intermembrane space (intrinsic apoptosis pathways).44 Activated caspase-8 is a key molecule that processes downstream effector caspases which subsequently cleave specific substrates resulting in cell death after death receptor ligation in extrinsic apoptosis. Bcl-2 proteins such Bax and Bak cause cytochrome c release from mitochondria, and cytochrome c forms the apoptosome which activates caspase-9 in intrinsic apoptosis. This pathway involves downregulation of Bcl-2 expression. We demonstrated that CS from activated CD4+VEGFR1high T cells highly triggered the activation of caspase-8 into target cells, but did not show the difference of Bcl-2 expression compared to that from activated CD4+VEGFR1− T cells. Therefore, apoptosis of CD4+CD25− T cells by CS from CD4+VEGFR1high T cells might be triggered through extracellular (extrinsic) apoptotic pathway including caspase-8 activation. CD95 (APO-1/Fas), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 1(TRAIL-R1) and TRAIL-R2 are the best-characterized death receptors as initiators for caspase-8 dependent apoptotic pathway.45,46 The corresponding ligands of the TNF superfamily are CD95 ligand (L), TNF-α, lymphotoxin-α, and TRAIL. CD95 L and TRAIL have not only membrane-bound forms but also soluble forms by proteolysis or alternative splicing.47 In addition, perforin and granzyme B directly cleave caspase-8, which mediates the induction of apoptosis through perf/GrB pathway.48 We suggest that candidates for apoptosis-mediated soluble factors from CD4+VEGFR1high T cells could be soluble forms of CD95L and TRAIL, perforin, and granzyme B. However, it has reported that CD95L and TRAIL have the severe toxic effect in membrane-forms than in soluble forms.47

We previously reported that CD4+VEGFR1+ T cells produced IL-10 after VEGF stimulation.24 Although VEGF signaling has no effect in CD4+VEGFR1high T-cell-mediated suppression (Figure 4), we wondered if IL-10 could lead to CD4+VEGFR1high T-cell-mediated suppression. As a result, the expression level of IL-10 between activated CD4+VEGFR1high and CD4+VEGFR1negative T cells had no difference and neutralizing anti-IL-10 Abs did not mitigate the suppressive activity. However, the addition of IL-2 to CD4+VEGFRhigh T cells during stimulation induced higher levels of IL-10 (data not shown). This result indicated that IL-10 could be a possible candidate of soluble factors which inhibit T-cell proliferation but not a major suppressive factor (data not shown). It is also of note that previous studies had reported that unlike neutralizing anti-IL-10 Ab, neutralizing anti-IL-10R Ab could affect the immune-suppressive activities of Tregs,49,50 which needs to be further investigated. We also found that the level of TGF-β in the CS of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells was below the detection limit (60 pg mL−1). IL-35 is also well-known factors in the mechanism of CD4+Foxp3+ T-cell-mediated suppression.16,51 IL-35 is a CD4+Foxp3+ T-cell-specific cytokine that is required for the maximal suppressive capacity in human and mouse,51,52,53 and it is also involved in regulation of mucosal immune responses.54 CD4+VEGFR1high T cells are not specifically Foxp3-expressing cells. However, the recent study showed that IL-35-mediated negative regulation of immune responses is not restricted to CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells.55 Some papers have reported that microRNA-containing or Fas ligand-expressing exosomes from Tregs or other tissues could mediate effector T-cell apoptosis.56,57,58 Taken together, CD4+VEGFR1high T-cell-mediated suppression might be exerted in various ways depending on the microenvironment, so that further studies to identify soluble factor(s) responsible for the suppressive activity should be considered under various circumstances.

IBD is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory disorder and one of the CD4+ T-cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. CD4+ T cells transferred into immune-deficient mice lead to IBD in response to enteric bacterial antigens derived from commensal microorganism, causing lethal weight loss and diarrhea due to endothelial and crypt hyperplasia as well as significant accumulation of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages within the lamina propria in the large intestine.31,59,60,61,62 In most human and mouse cases examined, IBD is associated with Th1-producing TNF and IFN-γ, which are important mediators of this disease.63,64 Th17 cells also have been suggested to play a key role in the pathogenesis of colitis and IBD, as they convert into Th1 cells and promote Th1 responses through IL-12 and IL-23.65,66 We found that adoptive transfer of CD4+VEGFR1−CD25− T cells into RAG2-deficient mice resulted in colitis seven weeks after transfer, whereas the co-transfer of CD4+VEGFR1+CD25− T cells did not induce colitis. The most prominent histopathological changes by CD4+VEGFR1−CD25− T-cell injection into RAG-2 KO mice were cellular infiltration, absence of crypts, and hypertrophy of all the layers of the colon. These results were consistent with those of previous studies.60,62

Therefore, we carefully suggest that understanding of suppressive mechanisms and successful ex vivo expansion of CD4+VEGFR1high T cells could contribute as the therapeutic potential of IBD or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health &Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant NO HI13C0954).

References

- 1Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 2008; 133: 775–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Gershon RK, Kondo K. Infectious immunological tolerance. Immunology 1971; 21: 903–914. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Gershon RK, Kondo K. Cell interactions in the induction of tolerance: the role of thymic lymphocytes. Immunology 1970; 18: 723–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol 1995; 155: 1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Bennett CL, Brunkow ME, Ramsdell F, O'Briant KC, Zhu Q, Fuleihan RL et al. A rare polyadenylation signal mutation of the FOXP3 gene (AAUAAA→AAUGAA) leads to the IPEX syndrome. Immunogenetics 2001; 53: 435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 2003; 299: 1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Groux H, Bigler M, de Vries JE, Roncarolo MG. Interleukin-10 induces a long-term antigen-specific anergic state in human CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med 1996; 184: 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Groux H, O'Garra A, Bigler M, Rouleau M, Antonenko S, de Vries JE et al. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature 1997; 389: 737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R, Bordignon C, Narula S, Levings MK. Type 1 T regulatory cells. Immunol Rev 2001; 182: 68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Roncarolo MG, Gregori S, Battaglia M, Bacchetta R, Fleischhauer K, Levings MK. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev 2006; 212: 28–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Levings MK, Sangregorio R, Sartirana C, Moschin AL, Battaglia M, Orban PC et al. Human CD25+CD4+ T suppressor cell clones produce transforming growth factor beta, but not interleukin 10, and are distinct from type 1 T regulatory cells. J Exp Med 2002; 196: 1335–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Weiner HL. Induction and mechanism of action of transforming growth factor-beta-secreting Th3 regulatory cells. Immunol Rev 2001; 182: 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Collison LW, Chaturvedi V, Henderson AL, Giacomin PR, Guy C, Bankoti J et al. IL-35-mediated induction of a potent regulatory T cell population. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Tang Q, Bluestone JA. The Foxp3+ regulatory T cell: a jack of all trades, master of regulation. Nat Immunol 2008; 9: 239–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8: 523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev 1997; 18: 4–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med 2003; 9: 669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Carmeliet P, Moons L, Luttun A, Vincenti V, Compernolle V, De Mol M et al. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med 2001; 7: 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Clauss M, Weich H, Breier G, Knies U, Röckl W, Waltenberger J et al. The vascular endothelial growth factor receptor Flt-1 mediates biological activities. Implications for a functional role of placenta growth factor in monocyte activation and chemotaxis. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 17629–17634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Barleon B, Sozzani S, Zhou D, Weich HA, Mantovani A, Marme D. Migration of human monocytes in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated via the VEGF receptor flt-1. Blood 1996; 87: 3336–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature 2005; 438: 820–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Dikov MM, Ohm JE, Ray N, Tchekneva EE, Burlison J, Moghanaki D et al. Differential roles of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in dendritic cell differentiation. J Immunol 2005; 174: 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Shin JY, Yoon IH, Kim JS, Kim B, Park CG. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced chemotaxis and IL-10 from T cells. Cell Immunol 2009; 256: 72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25McHugh RS, Whitters MJ, Piccirillo CA, Young DA, Shevach EM, Collins M et al. CD4(+)CD25(+) immunoregulatory T cells: gene expression analysis reveals a functional role for the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor. Immunity 2002; 16: 311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, Uede T, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi N et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med 2000; 192: 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol 2002; 3: 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Fohse L, Suffner J, Suhre K, Wahl B, Lindner C, Lee CW et al. High TCR diversity ensures optimal function and homeostasis of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol 2011; 41: 3101–3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Dumitriu IE, Mohr W, Kolowos W, Kern P, Kalden JR, Herrmann M. 5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester-labeled apoptotic and necrotic as well as detergent-treated cells can be traced in composite cell samples. Anal Biochem 2001; 299: 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Takeda I, Ine S, Killeen N, Ndhlovu LC, Murata K, Satomi S et al. Distinct roles for the OX40-OX40 ligand interaction in regulatory and nonregulatory T cells. J Immunol 2004; 172: 3580–3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Brimnes J, Reimann J, Nissen M, Claesson M. Enteric bacterial antigens activate CD4(+) T cells from scid mice with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol 2001; 31: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Ohm JE, Gabrilovich DI, Sempowski GD, Kisseleva E, Parman KS, Nadaf S et al. VEGF inhibits T-cell development and may contribute to tumor-induced immune suppression. Blood 2003; 101: 4878–4886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O'Shea KS et al. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 1996; 380: 439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi TP, Gertsenstein M, Wu XF, Breitman ML et al. Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk-1-deficient mice. Nature 1995; 376: 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Fong GH, Rossant J, Gertsenstein M, Breitman ML. Role of the Flt-1 receptor tyrosine kinase in regulating the assembly of vascular endothelium. Nature 1995; 376: 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Kondo S, Asano M, Matsuo K, Ohmori I, Suzuki H. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor is detectable in the sera of tumor-bearing mice and cancer patients. Biochim Biophys Acta 1994; 1221: 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Scaldaferri F, Vetrano S, Sans M, Arena V, Straface G, Stigliano E et al. VEGF-A links angiogenesis and inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Huang Y, Chen X, Dikov MM, Novitskiy SV, Mosse CA, Yang L et al. Distinct roles of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in the aberrant hematopoiesis associated with elevated levels of VEGF. Blood 2007; 110: 624–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Hattori K, Heissig B, Wu Y, Dias S, Tejada R, Ferris B et al. Placental growth factor reconstitutes hematopoiesis by recruiting VEGFR1(+) stem cells from bone-marrow microenvironment. Nat Med 2002; 8: 841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Clark RA, Chong B, Mirchandani N, Brinster NK, Yamanaka K, Dowgiert RK et al. The vast majority of CLA+ T cells are resident in normal skin. J Immunol 2006; 176: 4431–4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Ganusov VV, De Boer RJ. Do most lymphocytes in humans really reside in the gut? Trends Immunol 2007; 28: 514–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42Park MJ, Shin JS, Kim YH, Hong SH, Yang SH, Shin JY et al. Murine mesenchymal stem cells suppress T lymphocyte activation through IL-2 receptor alpha (CD25) cleavage by producing matrix metalloproteinases. Stem Cell Rev 2011; 7: 381–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Wang H, Keiser JA. Vascular endothelial growth factor upregulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinases in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of flt-1. Circ Res 1998; 83: 832–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Fulda S, Debatin KM. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene 2006; 25: 4798–4811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Walczak H, Krammer PH. The CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and the TRAIL (APO-2L) apoptosis systems. Exp Cell Res 2000; 256: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46Siegmund D, Mauri D, Peters N, Juo P, Thome M, Reichwein M et al. Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD) and caspase-8 mediate up-regulation of c-Fos by Fas ligand and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) via a FLICE inhibitory protein (FLIP)-regulated pathway. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 32585–32590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Wajant H. CD95L/FasL and TRAIL in tumour surveillance and cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Res 2006; 130: 141–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48Medema JP, Toes RE, Scaffidi C, Zheng TS, Flavell RA, Melief CJ et al. Cleavage of FLICE (caspase-8) by granzyme B during cytotoxic T lymphocyte-induced apoptosis. Eur J Immunol 1997; 27: 3492–3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49Asseman C, Mauze S, Leach MW, Coffman RL, Powrie F. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med 1999; 190: 995–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50Powrie F, Carlino J, Leach MW, Mauze S, Coffman RL. A critical role for transforming growth factor-beta but not interleukin 4 in the suppression of T helper type 1-mediated colitis by CD45RB(low) CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med 1996; 183: 2669–2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51Collison LW, Pillai MR, Chaturvedi V, Vignali DA. Regulatory T cell suppression is potentiated by target T cells in a cell contact, IL-35- and IL-10-dependent manner. J Immunol 2009; 182: 6121–6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52Collison LW, Workman CJ, Kuo TT, Boyd K, Wang Y, Vignali KM et al. The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function. Nature 2007; 450: 566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53Chaturvedi V, Collison LW, Guy CS, Workman CJ, Vignali DA. Cutting edge: human regulatory T cells require IL-35 to mediate suppression and infectious tolerance. J Immunol 2011; 186: 6661–6666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 54Wirtz S, Billmeier U, McHedlidze T, Blumberg RS, Neurath MF. Interleukin-35 mediates mucosal immune responses that protect against T-cell-dependent colitis. Gastroenterology 2011; 141: 1875–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55Shen P, Roch T, Lampropoulou V, O'Connor RA, Stervbo U, Hilgenberg E et al. IL-35-producing B cells are critical regulators of immunity during autoimmune and infectious diseases. Nature 2014; 507: 366–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56Abusamra AJ, Zhong Z, Zheng X, Li M, Ichim TE, Chin JL et al. Tumor exosomes expressing Fas ligand mediate CD8+ T-cell apoptosis. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2005; 35: 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57Stenqvist AC, Nagaeva O, Baranov V, Mincheva-Nilsson L. Exosomes secreted by human placenta carry functional Fas ligand and TRAIL molecules and convey apoptosis in activated immune cells, suggesting exosome-mediated immune privilege of the fetus. J Immunol 2013; 191: 5515–5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58Okoye IS, Coomes SM, Pelly VS, Czieso S, Papayannopoulos V, Tolmachova T et al. MicroRNA-containing T-regulatory-cell-derived exosomes suppress pathogenic T helper 1 cells. Immunity 2014; 41: 89–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59Rudolphi A, Boll G, Poulsen SS, Claesson MH, Reimann J. Gut-homing CD4+ T cell receptor alpha beta+ T cells in the pathogenesis of murine inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol 1994; 24: 2803–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60Morrissey PJ, Charrier K, Braddy S, Liggitt D, Watson JD. CD4+ T cells that express high levels of CD45RB induce wasting disease when transferred into congenic severe combined immunodeficient mice. Disease development is prevented by cotransfer of purified CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med 1993; 178: 237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, Caddle LB, Coffman RL. Phenotypically distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells induce or protect from chronic intestinal inflammation in C. B-17 scid mice. Int Immunol 1993; 5: 1461–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62Claesson MH, Rudolphi A, Kofoed S, Poulsen SS, Reimann J. CD4+ T lymphocytes injected into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice lead to an inflammatory and lethal bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol 1996; 104: 491–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63Blumberg RS, Saubermann LJ, Strober W. Animal models of mucosal inflammation and their relation to human inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Immunol 1999; 11: 648–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, Menon S, Caddle LB, Coffman RL. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity 1994; 1: 553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65Liu ZJ, Yadav PK, Su JL, Wang JS, Fei K. Potential role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 5784–5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66Abraham C, Cho J. Interleukin-23/Th17 pathways and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15: 1090–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]