Abstract

The pathologies of tendon and ligament attachments are called enthesopathies. One of its types is enthesitis which is a characteristic sign of peripheral spondyloarthropathy. Clinical diagnosis of enthesitis is based on rather non-specific clinical signs and results of laboratory tests. Imaging examinations are highly promising. Numerous publications prove that enthesitis can be differentiated from other enthesopathic processes in an ultrasound examination or magnetic resonance imaging. However, some reports indicate the lack of histological criteria, specific immunological changes and features in imaging examinations that would allow the clinical diagnosis of enthesitis to be confirmed. The first part of the publication presents theories on the etiopathogenesis of enthesopathies: inflammatory, mechanical, autoimmune, genetic and associated with the synovio-entheseal complex, as well as theories on the formation of enthesophytes: inflammatory, molecular and mechanical. The second part of the paper is a review of the state-of-the-art on the ability of imaging examinations to diagnose enthesitis. It indicates that none of the criteria of inflammation used in imaging medicine is specific for this pathology. As enthesitis may be the only symptom of early spondyloarthropathy (particularly in patients with absent HLA-B27 receptor), the lack of its unambiguous picture in ultrasound and magnetic resonance scans prompts the search for other signs characteristic of this disease and more specific markers in imaging in order to establish diagnosis as early as possible.

Keywords: enthesopathy, enthesitis, etiopathogenesis, spondyloarthropathies, rheumatic diseases

Abstract

Patologie przyczepów ścięgien i więzadeł są określane mianem entezopatii. Jednym z rodzajów entezopatii jest zapalenie (enthesitis), które stanowi charakterystyczny objaw spondyloartropatii obwodowych. Enthesitis jest rozpoznawane przez klinicystów na podstawie mało specyficznych objawów klinicznych i wyników badań laboratoryjnych. Duże nadzieje wiązane są z badaniami obrazowymi. Wiele prac naukowych dowodzi możliwości różnicowania zapalenia entez z innymi procesami entezopatycznymi w badaniach ultrasonograficznych albo metodą rezonansu magnetycznego. W sprzeczności pozostają doniesienia wskazujące na brak kryteriów histologicznych, specyficznych zmian immunologicznych oraz cech w badaniach obrazowych pozwalających na potwierdzenie klinicznego rozpoznania zapalenia. W pierwszej części publikacji przedstawiono teorie etiopatogenezy entezopatii: zapalną, mechaniczną, kompleksu entezy, autoimmunologiczną i genetyczną oraz koncepcje powstawania entezofitów: zapalną, molekularną i mechaniczną. Druga część pracy stanowi przegląd aktualnej wiedzy na temat możliwości badań obrazowych w rozpoznawaniu enthesitis. Wskazuje on, że żadne ze stosowanych w badaniach obrazowych kryteriów zapalenia nie jest specyficzne dla tej patologii. Ze względu na fakt, że może być ono jedynym objawem spondyloartropatii w początkowym ich okresie (zwłaszcza u chorych z nieobecnym antygenem HLA-B27), brak jednoznacznego obrazu enthesitis w badaniach ultrasonograficznych i rezonansu magnetycznego wymaga poszukiwania innych objawów charakterystycznych dla tych chorób oraz bardziej specyficznych markerów w badaniach obrazowych w celu jak najszybszego ustalenia rozpoznania.

Introduction

Entheses are sites where tendons, ligaments, fasciae and joint capsules attach to bones ensuring reduction in mechanical stress on the border of tissues with various strength and elasticity(1). The pathologies of entheses are called enthesopathies. Inflammation (enthesitis) is one of them. It is believed that enthesitis may develop in the course of spondyloarthropathy (SpA)*, metabolic or endocrine diseases and secondary to (micro)injury(1–3).

According to the ASAS (Assessment of SpondyloArthritis) criteria of 2009, enthesitis is part of to the clinical picture of peripheral spondyloarthropathy and is observed in all its types(2). Some authors consider enthesitis a characteristic feature of spondyloarthropathy and the first clinical sign of this disease. Nevertheless, it is frequently ignored by both patients and physicians, which leads to considerable delay in diagnosis(4).

In the clinical practice, the diagnosis of enthesitis is based on clinical examination, including interview (pain at the site of an enthesis that subsides following physical exercise), and observing pain in an enthesis upon compression. These symptoms are non-specific since they are also present in other conditions, such as microdamage of enthesis or presence of degenerative lesions where various scars form following micro- or partial damage(5). A number of reports emphasize the relevance of imaging in diagnosing enthesitis. D'Agostino demonstrated features of enthesitis in ultrasound examinations (US) of 98% of patients with SpA(6). Nevertheless, our own study(7) does not confirm that US differentiates the etiology of pathological entheses (more details can be found in the Part 2 of this publication).

The discussion is complicated by the fact that some authors do not confirm the existence of “primary” enthesitis. If inflammation occurs it is associated with the initial phase of the healing process of injured entheses or structures that adhere to the tendon in the vicinity of the bone attachments – usually bursae or adipose tissue(8–10). On the other hand, the latest data obtained on animal models indicate that interleukin 23 (IL-23) may take part in initiating enthesitis. IL-23, which production in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is dependent on the intestinal bacterial flora (microflora), may in certain cases undergo enhanced expression and spread to other tissues in the body. A new subpopulation of T lymphocytes showing increased expression of receptors for IL-23 was found in entheses. If the population is present, the receptors undergo intensive activation and proliferation thus initiating inflammation. Conversly, their blockade reduces inflammation and prevents tissue from further destruction(11, 12).

Anatomy of entheses

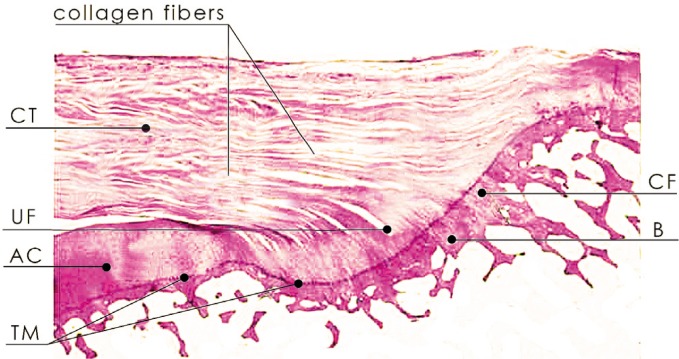

There are two types of entheses: fibrous and fibrocartilaginous(13). Due to their anatomic connection with a rigid material, i.e. bone, they are a common site for micro- and partial damage. According to the literature, they are at the same time predilection areas for spondyloarthropathy. In SpA, the disease affects mainly the entheses that are subject to mechanical stress, especially the fibrocartilaginous ones(13–15). They are made of four parts(14): 1. fibrous part (loosely and longitudinally arranged fibroblasts and dense fibrous connective tissue); 2. non-calcified fibrocartilage (FC) with dominating chondrocytes and extracellular matrix with proteoglycans that constitutes a barrier for vessels and cells; 3. calcified fibrocartilage and 4. bone (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal section of the fibrocartilaginous enthesis of the supraspinatus muscle tendon: dense connective tissue (CT), non-calcified fibrocartilage (UF), calcified fibrocartilage (CF) and bone (B)

Fibrocartilage is a transitional tissue between dense fibers of the connective tissue and cartilage, which has been formed as a result of enthesis adaptation to the compression-like stress(14), as in the wall of the Achilles tendon bursa, where so-called periosteal FC covers the posterior aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity (calcaneal bursal wall). The other, so-called sesamoid FC, develops in the ventral part of the Achilles tendon (tendinous bursal wall) and during the movement of the foot it “wraps itself” over the upper part of the calcaneal tuberosity(14). Like tendons, noncalcified fibrocartilage contains type I, III, V and VI collagen and proteoglycans (decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin and lumican) as well as type II collagen and aggrecan that are also found in the cartilage(14). The periosteal and sesamoid FC are neither vascularized nor innervated. This may partially result from the presence of aggrecan, which main glycosaminoglycan – chondroitin sulfate – is an axonal growth inhibitor in the central nervous system. In elderly patients, degeneration causes the appearance of vessels and nerves in the FC(8, 16).

Enthesopathies including enthesitis

The OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatologic Clinical Trials)(4) enthesopathy definition is: “Abnormal hypoechoic (loss of normal fibrillar architecture) and/or thickened tendon or ligament at its bony attachment (may occasionally contain hyperechoic foci consistent with calcification) seen in two perpendicular planes that may exhibit Doppler signal and/or bony changes including enthesophytes, erosions, or irregularity”(4). According to the authors’ opinion, this definition reflects a range of changes observed in imaging examinations (particularly US) in pathologically altered entheses, which in correlation with histological findings result from:

lower echogenicity (hypoechogenicity) of enthesis – results from the loss of its normal fibrillar structure caused by damage and edema or presence of irregular scar;

thickened enthesis – results from altered structure of the collagen fibers which undergo breaking and unfolding and thus have a greater volume;

calcification (mineralization) and ossification – result from healing processes of microdamage and scar formation;

irregular outline of the entheseal osseous elements – results from the pathological process involving the FC or entheseal bony component thereby leading to cortical bone defects, i.e. inflammatory cysts and erosions.

The term enthesitis was introduced by La Cava in 1959 to describe a process observed in entheses following mechanical injury. In 1971, Ball found that this pathology is a characteristic feature of ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Then, in the 1980s, a hypothesis of enthesitis was extended to include all types of spondyloarthropathies(14). It is currently believed that enthesitis is one of the main signs of SpA, especially in the peripheral type, and may be the only manifestation of this disease for a long time(17, 18). Therefore, this part of SpA's clinical picture has become the basis for a range of indices for diagnosing and monitoring different types of spondyloarthropathies, e.g. Mander Enthesis Index, Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score, Major Enthesitis Index, Gladman Index and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index(19). In 2009, enthesitis was also included in the ASAS classification criteria of SpA despite the fact that in the previous years, the term “enthesopathy” had been used in Amor's and ESSG's (European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group)(20) criteria.

As mentioned before, the diagnosis of enthesitis is based on the clinical picture, mainly interview and pain upon compression with edema at the site of an enthesis. Based solely on these signs, the diagnosis of SpA is frequently made. Laboratory tests (ESR and CRP) are also non-specific and HLA-B27 antigen in peripheral type of SpA is present in merely 30–70% of cases(21). These data indicate how difficult it is to diagnose enthesitis. At the same time, such a diagnosis is an essential criterion for qualification to biological treatment in psoriatic arthritis (PsA, one of SpA types) in many countries.

Pathogenesis of enthesitis

Inflammatory theory

There is no unambiguous definition or histopathological criterion for enthesitis(14) so far. This mainly results from the difficulties in obtaining samples for a histopathological analysis in rheumatic patients(18). Some authors confirm the existence of the inflammatory process whereas others suggest the presence of transient inflammation secondary to enthesis damage, which subsequently subsides to enable anti-inflammatory and repair processes(22–24).

In 1971, Ball introduced histopathology-based diagnosis of enthesitis in patients with AS(18). Inflammatory infiltration consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells was localized in the subchondral layer where it induced erosive processes followed by fibrous tissue proliferation with secondary formation of cartilage, and subsequently, bone(18). The existence of inflammation in the osseous part of entheses was confirmed in other studies(14). In the subchondral region of bone adjacent to entheses in patients with AS and PsA, large counts of CD3+ and CD20+ lymphocytes were found and in the synovial membrane and fluid CD4+ lymphocytes were prevalent(14, 25). Moreover, unlike patients with RA, those with AS manifested prevalence of T CD8+ lymphocytes in the bony part and synovial membrane of entheses(14, 25). The authors concluded that they might play the crucial role in the pathogenesis of enthesitis in SpA(14).

Mechanical theory

Patients with clinical signs of enthesitis of the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia manifested increased vascularity and cellular infiltration within the FC part of the enthesis(18). It is proven that inflammation is triggered by a mechanical factor, so-called micro- or partial damage of the FC, that leads to the activation of the innate immune system, mainly macrophages(8). This was confirmed in subsequent papers published in 2000 and 2001(26). At present, more and more damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) are identified to trigger such an immune response at the sites of microdamage(8).

Apart from the activation of the innate immune system, a factor that damages the FC of entheses, irrespective of its nature (mechanical, infectious or stress-related), may induce inflammatory response involving the activation of Toll-like receptors (TLR) which belong to the group of pattern-recognition receptors that identify characteristic structures of microbes such as bacterial or viral DNA, RNA etc. and dendritic cells. According to this hypothesis, TLRs are activated as a result of the deposition of auxiliary molecules originating from intestinal bacteria at the site of FC damage(8, 25).

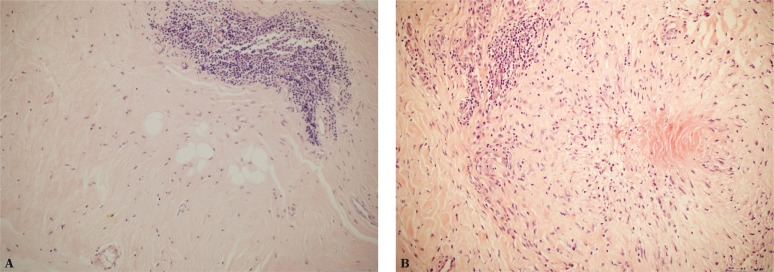

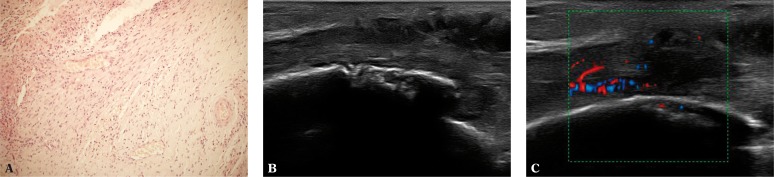

Macrophages activated by enthesis damage begin secreting proinflammatory cytokines M1 (TNF-α, IL-18, 12 and 23), prostaglandins (e.g. PGE2), nitric oxide, various growth factors and neuropeptides(27). This is followed by apoptosis, release of pain mediators and matrix metalloproteinases which degrade collagen and proteoglycans. Studies conducted in our center confirmed that(28) (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A. Focal inflammatory infiltration of lymphoid cells in the area of a tendon enthesis (200x magnification, H&E stain); B. Focal necrosis and chronic inflammatory infiltration in the region of a tendon enthesis (200x magnification, H&E stain)

Subsequently, in normal conditions, which constitute the majority, i.e. in typical mechanical microdamage of an enthesis, we observe sequential secretion of immunosuppressive IL-10 and IL-13 cytokines which signal M2 macrophages to switch the phenotype from M1 to M2, stop inflammation processes, reduce TLR reactivity and suppress production of proinflammatory cytokines. According to some hypotheses, in certain situations, such as in rheumatic diseases, stopping inflammation is not always effective and then, a chronic inflammation develops which may lead to irreversible damage to the articular structures. Today, we know that in RA, TNF-α cytokine produced by M1 macrophages stimulates synovial fibroblast-like synoviocytes to secrete proinflammatory cytokines. The inflammation progresses. It is not known, however, how it occurs in SpA.

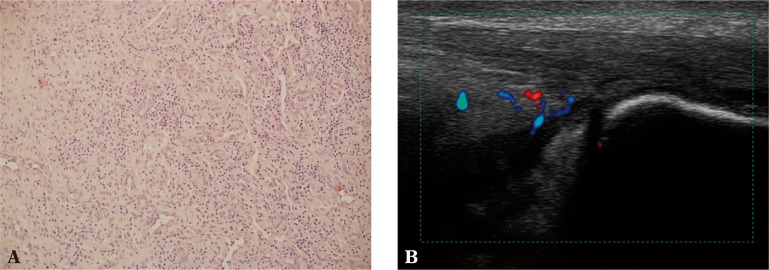

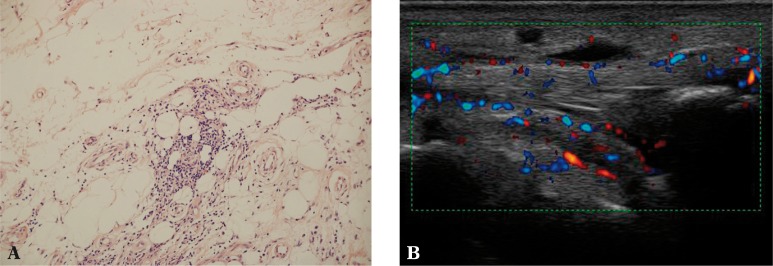

Synovio-entheseal complex theory

Benjamin and McGonagle observed interrelations between an enthesis and adjacent synovial membrane of the bursa or adipose tissue and introduced the term “synovioentheseal complex” (SEC)(3, 8, 25). They drew attention to the inflammatory potential of the tissues that surround entheses and are related to it by function (in terms of mechanical stress dissipation) as fundamental factors in the etiopathogenesis of enthesitis(13). According to the SEC theory, micro- or partial damage to entheses may activate the mechanisms of the innate immune system and stimulate rapid development of bursitis (fig. 3). The authors provide a similar explanation for their “functional enthesis” theory, according to which the conflict of the tendon moving in the vicinity of the bone, which acts as a pulley (e.g. tibialis posterior tendon and medial malleolus), may cause tenosynovitis (fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

A. Synovium of the Achilles tendon with inflammatory granulation consisting of numerous small vessels and chronic inflammatory infiltrations of lymphoid cells (100x magnification, H&E stain); B. Effusion as well as thickened and vascularized synovium of the Achilles tendon bursa (bursitis) in US

Fig. 4.

A. Inflammatory infiltration in the area of the sheath extending onto the tendon (200x magnification, H&E stain); B, C. Erosions on the medial malleolus in the course of chronic tibialis posterior tenosynovitis

Benjamin et al.(3, 8, 25) also demonstrated proinflammatory potential of the adipose tissue of tendons and surrounding tissues. The adipose tissue is localized on the surface of the tendon in the epitendon, between fiber bundles (endotendon fat), in the angle between an enthesis and adjacent bone (insertional angle as e.g. the adipose tissue of the quadriceps femoris tendon), in the area of the tendon (e.g. adipose tissue of the Hoffa's body or Kager triangle) and in the bursa (so-called meniscoid fat, e.g. adipose fold of the Kager triangle which, being the component of the Achilles tendon bursa, exhibits proinflammatory potential and is additionally lined with the synovial membrane)(9, 10, 29).

Adipose tissue exhibits endocrine or paracrine activity and releases growth factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is vascularized and innervated. It may be a source of pain and play a role in the inflammatory response(9, 13) (fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

A. Quite numerous inflammatory infiltrations of lymphocytes in the extra-articular adipose tissue (200x magnification, H&E stain); B. Edema and hyperemia of the adipose tissue of the flexor compartment in the course of tibialis posterior tenosynovitis

The blood vessels that appear in tendons in the course of inflammatory and inflammatory-repair processes may originate from the adipose tissue adjacent directly to the tendon (patellar ligament, the quadriceps tendon), from the paratenon (Achilles tendon), from the loose connective tissue in the area of the tendon, and from the mesentery of the tendon (e.g. sheath tendons and the Achilles tendon).

The vessels found in entheses may also originate from the bone marrow(8). The vascular invasion is facilitated by the lack of the periosteum in entheses, which enables the stem cells of the bone marrow to gain direct access to the soft tissues of entheses and facilitates enthesis repair (see: Pathogenesis of enthesophytes). In fibrocartilaginous entheses, FC degeneration or partial loss of the FC creates favorable conditions for the vascular invasion of the bone marrow capillary vessels (see: Pathogenesis of enthesophytes)(8, 13, 25).

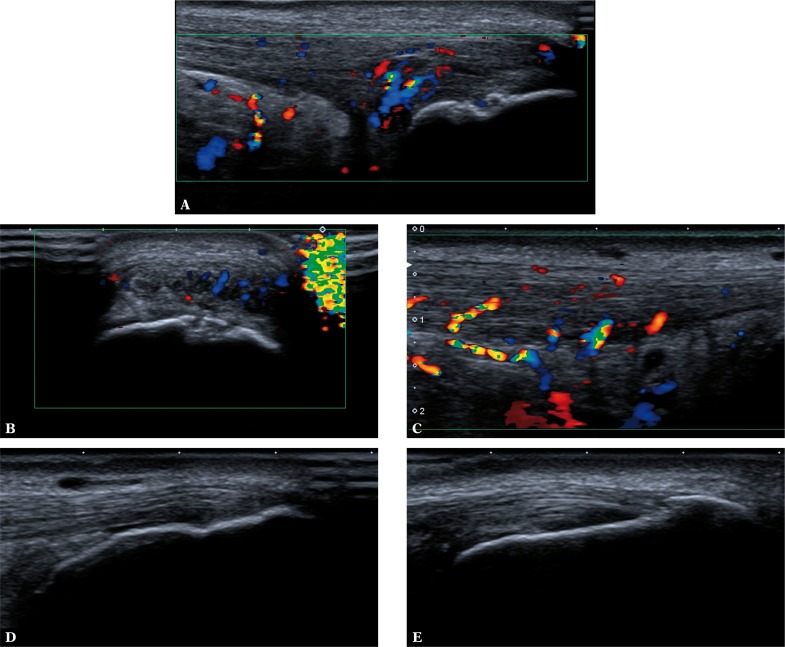

Invasive blood vessels proliferate within tendon or ligament entheses, frequently leading to multidirectional damage resulting from chronic inflammation, or they participate in the repair processes. The patient may manifest clinical symptoms of enthesitis, but in imaging examinations, we are unable to determine the order of events: whether inflammation of the adipose tissue in the vicinity of an enthesis was triggered by microdamage that presents with e.g. an enthesophyte, or whether the primary inflammatory process occurred in the adipose tissue (or in the bursa) and the enthesophyte observed is a mineralized scar after healed stress (microdamage), which has no causal relationship with the pathology of tissues surrounding the enthesis. Our own prospective US observations based on the calcaneal tuberosity enthesis do not currently allow the conclusions to be specified. In patients with clinically diagnosed enthesitis, we observe cases of bursitis or inflammation of the adipose tissue in the Kager triangle in normal as well as altered image of the enthesis(7) (fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Achilles tendons in a patient with clinically diagnosed enthesitis. On the right (A, B): tenosynovitis with the presence of inflammatory and repair process vessels penetrating into the damaged Achilles tendon; active erosion in the calcaneal wall of the bursa (A, B); mineralized scar following partial damage of the enthesis in the proximal part of the attachment (A). On the left (C, D, E): intratendinous damage to the Achilles tendon with inflammatory and repair process vessels originating from the fat pad of the Kager triangle; the bursa is normal (D); chronic enthesopathic lesions visible as areas of enhanced echogenicity of FC and blurred bone outline (D) as well as mineralized scars (E) which correspond to remodeled scars after cartilage microdamage sustained in the past

Autoimmune theory

Another mechanism postulated to occur in the pathogenesis of enthesitis is an autoimmune process. Aggrecan – a large proteoglycan, which is a component of the FC and cartilage, may be a potential autoantigen in the fibrocartilage of patients with SpA. When implanted in mice, it caused peripheral arthritis and spondylitis(14). The content of aggrecan and the link protein increases upon compression in tendons whereas type I collagen is replaced by type II (gap phenomenon)(13). In rheumatic patients, these molecules were identified as autoantigens of the autoimmune response(13). A similar mechanism is discussed in terms of SpA(13). Nevertheless, not all authors agree that the FC is the site where enthesitis starts in spondyloarthropathy since SpA also includes fibrous entheses(14).

Genetic theory

In the past years, intensive studies have been conducted on genes coding numerous proteoglycans and glycoproteins that play a key role in the development, structure and function of tendons, ligaments and entheses. Not only will they allow us to learn more about the etiopathogenesis of diseases or pathological lesions, but will also facilitate genetic therapies that will inhibit pathogenetic mechanisms, such as enthesopathy, in the future(30, 31). For instance, it is known that the presence of 9q33 chromosome is associated with the predisposition to Achilles tendon injuries. A similar effect was observed in the absence of the fibromodulin: fibers underwent reduction, had various diameters, uneven outlines, their arrangement was disturbed and the number of cells and amount of the endotendon was reduced. Studies on mice demonstrated the development of ectopic calcification in the Achilles tendon in the case of the lack of biglycan and fibromodulin. The absence of proteoglycan 4 led to the development of calcifications (calcified scars) in tendons and tendon sheaths(32).

Pathogenesis of enthesophytes

Enthesophytes are one of the most common manifestations of enthesopathies in imaging. They are considered a unique feature of spondyloarthropathy, which distinguishes it from RA(32) (fig. 7). Various hypotheses concerning the formation of enthesophytes suggest the role of inflammatory and mechanical factors as well as molecular mechanisms involving mesenchymal cells.

Fig. 7.

Ossified scars (enthesophytes) in the calcaneal tendon enthesis seen in US (A) and X-ray (B), called upper calcaneal spur

Inflammatory theory

According to the inflammatory theory, the starting point of new bone formation is an inflammatory process, and more specifically – macrophages capable of producing TGF-β cytokine and bone morphogenetic proteins (BPMs) which influence cartilage differentiation and ossification processes(14, 32). Despite the fact that some of the key proinflammatory cytokines in AS, i.e. TNF, IL-1 and IL-17, inhibit ossification processes, TGF-β and BMPs lead to the formation of enthesophytes. This mechanism has not been entirely explained yet. It remains unknown why the cancellous bone, in which osteoporosis with secondary fractures occurs in AS, behaves differently to the cortical layer, in which new bones, syndesmophytes and enthesophytes are formed. It is probable that the cortical layer does not have receptors for the above mentioned cytokines.

Moreover, T lymphocytes were detected(32), which indicates IL-23 receptor expression and response to these cytokines in entheses. IL-23 overexpression led to destructive lesions in entheses with simultaneous formation of a new bone (enthesophyte). The IL-22 interleukin induced osteoblasts differentiation via Wnt and BMPs. Other cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-17, IL-18, IL-33 and oncostatin M, also have osteogenic effects. This is a proof for the fact that apart from its catabolic activity the immune system may, under certain conditions, exhibit anabolic activity as well.

Molecular theory

Another hypothesis indicates that enthesophytes (just as osteophytes and syndesmophytes) originate from the mesenchymal cells(33). The differentiation of precursor mesenchymal cells into enthesophytes is enabled by three groups of molecules: PGE2, BMPs and Wnt. It is not yet known whether these bony spurs (broadly speaking osteophytes), including structures localized in the peripheral joints (osteophytes in the strict sense), in entheses (enthesophytes) and along the vertebral column (spondylophytes, syndesmophytes), develop through the same molecular mechanism. Currently, we know about two basic paths of their development: endochondral ossification and membranous ossification, including chondroid metaplasia. Studies conducted in humans and mice revealed the presence of hypertrophic chondrocytes, which indicates endochondral bone formation in the spinal and peripheral joints, as well as membranous bone formation and chondroid metaplasia(33).

Mechanical theory

According to the mechanical theory, enthesophytes constitute a type of a repair reaction to mechanical stress (microdamage) of the tendon or ligament and lead to damage to the FC (in fibrocartilaginous entheses) and rarely to the periosteum (in fibrous entheses)(13). In the latter case, osteoblasts originate from the mesenchymal precursor cells, which cover the intact periosteum. As a result of irritation (damage) of the periosteum, osteoblasts differentiate and form new bones (enthesophytes, syndesmophytes). The differentiation and activation of osteoblasts are regulated by various molecular signals, such as PGE2 that induces an anabolic effect on bone formation. Moreover, it acts together with the family of TGF/BMP proteins in inducing ossification. Wnt proteins also play a significant role in bone and syndesmophyte formation(33). The lack of suppression of signals transmitted by Wnt/β-catenins led to the development of large osseous lesions (enthesophytes, syndesmophytes)(32).

In fibrocartilaginous entheses, the proximity of non-calcified fibrous cartilage to the bone enables endochondral ossification(25). At first, invasion of the vessels to the fibrocartilage occurs(25). Fibrocartilaginous entheses, and more specifically the FC itself, do not have openings (canals) for vessels. However, histopathological examinations reveal that due to FC degeneration, “tunnels” form within the rows of FC cells. These “tunnels” serve as a way for capillaries and mesenchymal stem cells of the bone marrow into the fibrous part of an enthesis which subsequently become filled with the bone tissue(14, 25). The problem with bone marrow-enthesis communication does not concern fibrous entheses that do not possess the FC barrier thanks to which blood flows easily between the ligament or tendon and bone. Such a situation occurs rarely, but is possible in the case of fibrocartilaginous entheses in which the continuity of FC is partially lacking. In such sites, an enthesis has the features of a fibrous attachment, which facilitates communication with the bone marrow(25).

Conclusion

The presented above review of the state-of the-art concerning the etiopathogenesis of enthesopathy, including enthesitis, demonstrates how many issues still remain unexplained at the histopathological and immunological levels. This generates a number of questions and difficulties in interpreting imaging findings, which will be presented in the second part of the article.

Footnotes

Spondyloarthropathies are the second most common group of rheumatic diseases that includes five entities: ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, arthritis concomitant with non-specific inflammatory bowel disease and undifferentiated spondyloarthropathies. Depending on the predominant symptoms, i.e. sacroiliac arthritis or spondylitis, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis or finger arthritis, SpAs may be divided into axial and peripheral types.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not report any financial or personal connections with other persons or organizations, which might negatively affect the contents of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Eshed I, Bollow M, McGonagle DG, Tan AL, Althoff CE, Asbach P, et al. MRI of enthesitis of the appendicular skeleton in spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1553–1559. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.070243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Agostino MA. Role of ultrasound in the diagnostics work-up of spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:375–379. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328354612f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin M, McGonagle D. The enthesis organ concept and its relevance to the spondyloarthropathies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;649:57–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0298-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filipucci E, Aydin SZ, Karadag O, Salaffi F, Gutierrez M, Direskeneli H, et al. Reliability of high-resolution ultrasonography in the assessment of Achilles tendon enthesopathy in seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1850–1855. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Miguel E, Muñoz-Fernández S, Castillo C, Cobo-Ibáñez T, Martín-Mola E. Diagnostic accuracy of enthesis ultrasound in the diagnosis of early spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:434–439. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Agostino MA, Aegerter P, Jousse-Joulin S, Chary-Valckenaere I, Lecoq B, Gaudin P, et al. How to evaluate and improve the reliability of power Doppler ultrasonography for assessing enthesitis in spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:61–69. doi: 10.1002/art.24369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Zaniewicz-Kaniewska K, Kwiatkowska B. Spectrum of ultrasound pathologies of Achilles tendon, plantar aponeurosis and flexor digiti brevis entheses in patients with clinically suspected enthesitis. Pol J Radiol. 2014 doi: 10.12659/PJR.890803. [w druku] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin M, McGonagle D. The enthesis organ concept and its relevance to the spondyloarthropathies. In: López-Larrea C, Diaz-Peña R, editors. Molecular mechanisms of spondyloarthropathies. New York: Landes Bioscience and Springer Science + Business Media; 2009. pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Kontny E, Zaniewicz-Kaniewska K, Prohorec-Sobieszek M, Saied F, Maśliński W. Role of inflammatory factors and adipose tissue in pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Part I: Rheumatoid adipose tissue. J Ultrason. 2013;13:192–201. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2013.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Hrycaj P, Prohorec-Sobieszek M. Role of inflammatory factors and adipose tissue in pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Part II: Inflammatory background of osteoarthritis. J Ultrason. 2013;13:319–328. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2013.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGonagle D, Wakefield RJ, Tan AL, D'Agostino MA, Toumi H, Hayashi K, et al. Distinct topography of erosion and new bone formation in achilles tendon enthesitis: implications for understanding the link between inflammation and bone formation in spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2694–2649. doi: 10.1002/art.23755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emad Y, Ragab Y, Gheita T, Anbar A, Kamal H, Saad A, et al. Knee Enthesitis Working Group: Knee enthesitis and synovitis on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with psoriasis without arthritic symptoms. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1979–1986. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin M, Toumi H, Ralphs JR, Bydder G, Best TM, Milz S. Where tendons and ligaments meet bone: attachment sites (“enthuses”) in relation to exercise and/or mechanical load. J Anat. 2006;208:471–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.François RJ, Braun J, Khan MA. Entheses and enthesitis: a histopathologic review and relevance to spondyloarthritides. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:255–264. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tei MM, Farraro KF, Woo SLY. Structural Interfaces and Attachements in Biology. New York: Springer; 2013. Ligament and Tendon Enthesis: Anatomy and Mechanics; pp. 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw HM, Santer RM, Watson AHD, Banjamin M. Adipose tissue at entheses: the innervations and cell composition of the retromalleolar fat pad associated with the rat Achilles tendon. J Anat. 2007;211:436–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feydy A, Lavie-Brion MC, Gossec L, Lavie F, Guerini H, Nguyen C, et al. Comparative study of MRI and power Doppler ultrasonography of heel in patients with spondyloarthritis with and without heel pain and in controls. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:498–503. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Healy P, Helliwell PS. Measuring clinical enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis: assessment of existing measures and development of an instrument specific to psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:686–691. doi: 10.1002/art.23568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong PC, Leung YY, Li EK, Tam LS. Measuring disease activity in psoriatic arthritis. Int J Rheumatol. 2012;2012:839425. doi: 10.1155/2012/839425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sparado A, Iagnocco A, Perrotta FM, Modesti M, Scarno A, Valesini G. Clinical and ultrasonography assessment of peripheral enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology. 2011;50:2080–2086. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMichael A, Bowness P. HLA-B27: natural function and pathogenic role in spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res. 2002;4(Suppl. 3):S153–S158. doi: 10.1186/ar571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braem K, Deroose CM, Luyten FP, Lories RJ. Inhibition of inflammation but not ankylosis by glucocorticoids in mice: further evidence for the entheseal stress hypothesis. Arthirits Res Ther. 2012;14:R59. doi: 10.1186/ar3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, Chao CC, Sathe M, Grein J, Gorman DM, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-(t(+) CD3(+) CD4(-)CD8(-) entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1069–1076. doi: 10.1038/nm.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benham H, Rehaume LM, Hasnain SZ, Velasco J, Baillet AC, Ruutu M, et al. IL-23-mediates the intestinal response to microbial beta-glucan and the development of spondyloarthritis pathology in SKG mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Mar; doi: 10.1002/art.38638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamin M, McGonagle D. The anatomical basis for disease localisation in seronegative spondyloarthropathy at entheses and related sites. J Anat. 2001;199:503–526. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19950503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Agostino MA, Palazzi C, Olivieri I. Entheseal involvement. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(Suppl. 55):S50–S55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fredberg U, Ostgaard R. Effect of ultrasound-guided, peritendinuous injections of adalimubab and anakinra in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a pilot study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19:338–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prochorec-Sobieszek M, Małdyk P. Obraz mikroskopowy ścięgien i pochewek ścięgnistych w przypadkach reumatoidalnego zapalenia stawów. Reumatologia. 1993;31:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamin M, Redman S, Milz S, Büttner A, Amin A, Moriggl B, et al. Adipose tissue at entheses: the rheumatological implications of its distribution. A potential site of pain and stress dissipation? Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1549–1555. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.019182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Rielly DD, Rahman P. Advances in the genetics of spondyloarthritis and clinical implications. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15:347. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hébert HL, Ali FR, Bowes J, Griffiths CE, Barton A, Warren RB. Genetic susceptibility to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: implications for therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:474–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldring SR. Osteoimmunology and bone homeostasis: relevance to spondyloarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15:342. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schett G, Rudwaleit M. Can we stop progression of ankylosing spondylitis? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]