Abstract

Ultrasound examination is a valuable method in diagnosing visceral vasoconstriction of atherosclerotic origin, as well as constriction related to the compression of the celiac trunk. Given the standard stenosis recognition criteria of >70%, the increase in peak systolic velocity (PSV) over 200 cm/s in the celiac trunk; of PSV > 275 cm/s in the superior mesenteric artery, and of PSV > 250 cm/s in the inferior mesenteric artery, the likelihood of correct diagnosis is above 90%. In the case of stenosis due to compression of the celiac trunk by median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm, a valuable addition to the regular examination procedure is to normalize the flow velocity in the vessel, i.e. the reduction in peak systolic velocity levels below 200 cm/s, and in end-diastolic velocity (EDV) levels below 55 cm/s during deep inspiration. In the case of celiac trunk stenosis exceeding 70–80%, additional information on the level of collateral circulation can be obtained by measuring the flow in the hepatic and splenic arteries – assessing the flow velocity, resistance, and pulsatility indices (which fall below 0.65 and below 1.0 in cases of stenosis of the celiac trunk with a reduced capacity of collateral circulation), as well as assessing the changes in these parameters during normal respiration and during inspiration. This paper discusses in detail the examination methods for the celiac trunk and mesenteric arteries, as well as additional procedures used to confirm the diagnosis and pathologies affecting visceral blood flow velocity, i.e.: cirrhosis and hypersplenism. The publication is an update of the Polish Ultrasound Society guidelines published in 2011.

Keywords: mesenteric arteries, celiac trunk, arcuate ligament syndrome, mesenteric ischemia

Abstract

Badanie USG jest cenną metodą służącą do rozpoznawania zwężeń naczyń trzewnych – zarówno pochodzenia miażdżycowego, jak i związanego z uciskiem na pień trzewny. Przy stosowanych kryteriach rozpoznania zwężenia >70% dla pnia trzewnego wzrost prędkości szczytowo-skurczowej (PSV) do >200 cm/s oraz w tętnicy krezkowej górnej PSV >275 cm/s i tętnicy krezkowej dolnej PSV >250 cm/s prawdopodobieństwo postawienia prawidłowego rozpoznania wynosi powyżej 90%. W przypadku zwężeń spowodowanych uciskiem na pień trzewny przez krzyżujące się w okolicy jego odejścia od aorty odnogi przepony – więzadła łukowate – cennym uzupełnieniem badania potwierdzającym rozpoznanie jest normalizacja prędkości przepływu w naczyniu, tj. jej spadek w zakresie prędkości szczytowo-skurczowej poniżej 200 cm/s oraz końcowo-rozkurczowej poniżej 55 cm/s. W przypadku zwężeń pnia trzewnego przekraczających 70–80% dodatkowe informacje na temat stopnia rozwoju krążenia obocznego można uzyskać, mierząc przepływy w tętnicy wątrobowej i śledzionowej – oceniając zarówno prędkości przepływu, wskaźniki oporności oraz pulsacyjności (obniżające się poniżej 0,65 i poniżej 1,0 w przypadkach zwężenia pnia trzewnego bez rozwiniętego krążenia obocznego), jak zmiany powyższych parametrów w czasie normalnego oddychania oraz wdechu. Omówiono szczegółowo technikę badania pnia trzewnego i tętnic krezkowych, a także dodatkowe elementy potwierdzające rozpoznanie oraz patologie mogące zmieniać prędkości przepływu w naczyniach trzewnych – marskość wątroby, hipersplenizm. Publikacja stanowi aktualizację standardów Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego wydanych w roku 2011.

Introduction

The correct understanding of complex circulation within the celiac trunk and mesenteric arteries and their interactions serves as the foundation for reliable diagnostics, as well as the basis for accurate diagnosis. The visceral arteries include: celiac trunk, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), extending from the upper part of the front wall of the abdominal aorta above the renal arteries, and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), departing from the front-left anterolateral wall of the aorta a few centimeters below renal vessels. These vessels are separated by a short distance and are connected circumferentially to allow blood flow between them, the levels of which – to varying degrees – change with age and with the degree and severity of pathological changes.

The celiac trunk supplies blood to abdominal organs: liver, gallbladder (and bile ducts), pancreas, spleen, and the abdominal intestinal structures: the stomach, duodenum, and the proximal part of the jejunum. The superior mesenteric artery delivers blood to the large intestine from the cecum to the splenic flexure, while the distal part of the colon is supplied with blood by the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 1). The visceral trunk and SMA connect directly to the gastro-duodenal artery. Both mesenteric arteries – SMA and IMA – are connected by meandering mesenteric artery (arc of Riolan) the marginal artery of the colon (artery of Drummond). There is also a connection between the IMA and the internal iliac arteries(1).

Fig. 1.

Common origin of coeliac artery and superior mesenteric artery

Equipment

Ultrasound imaging is performed using a standard 2–5 MHz probe. Due to the need to record high-speed flows (2,5–2,75 m/s in healthy subjects, and – in some cases – of more than 4 m/s in the case of lesions), high-end units using triplex mode are recommended. Due to the greater stability in examining the position of the aorta and the SMA, and usually a large measurement angle, the examination of the mesenteric artery can be performed in duplex, where the B-mode image is frozen.

Examination preparation

The patient should refrain from eating for 6–8 hours before the examination. Due to the nature of evaluation of abdominal vascular structures, the patients should also abstain from taking any fluids for at least 2 hours prior to the examination.

Examination procedure

The examination is performed by positioning the patient in the supine position, with the patient breathing freely; the probe is positioned over the celiac trunk during exhalation, the recording speed is set to triplex mode. Due to changes in blood flow to the celiac trunk during deep breathing, the assessment of stenosis during inspiration is impossible.

The examination is typically carried out in the longitudinal plane – along the axis of the middle-upper section of the vessel – which is necessary for the proper determination of the angle between the axis of the blood stream and the direction of the Doppler wave (Fig. 2A, B). In the absence of clearly identifiable stenosis or a post-stenotic dilation, the scanning probe should also be positioned over the entire length of the vessel in order to check for significant changes in the flow velocity within. In cases of stenosis identified in B-mode, the probe should be placed in the upper edge of the stenosis, before the post-stenotic dilation, or – in the case of visible pressure – the entire bend should be examined for changes in flow velocity. This should be followed by examination performed during the end-inspiratory pause. Stenosis associated with the pressure by the arched ligaments during inhalation will move them to a higher position and cause the “unblocking” of the celiac trunk, as well as a significant decrease in flow velocity within, in most cases reaching normal levels (Fig. 3A–G). In the case of clearly visible stenosis, it is recommended to supplement the study of flow measurements in the hepatic and splenic arteries, preferably during free breathing and maximal inspiration.

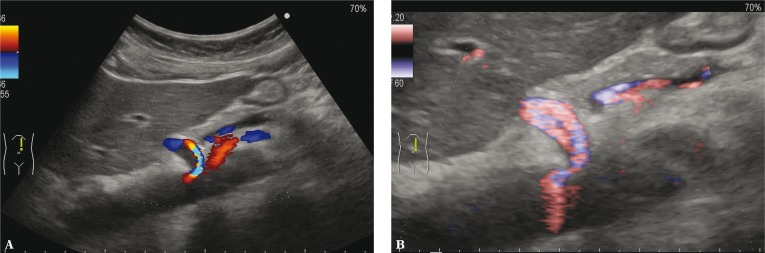

Fig. 2.

A. Morphological image – stenosis. B. Morphological image – stenosis PD

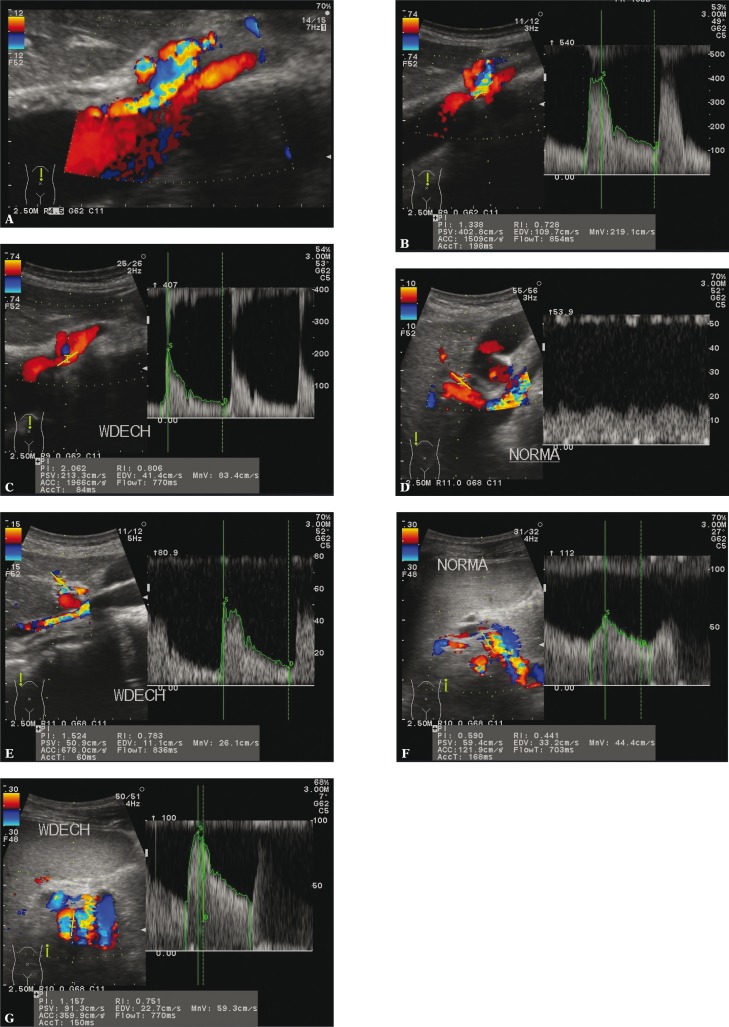

Fig. 3.

A. The morphological – celiac trunk stenosis – median arcuate ligament syndrome. B. The increase in flow velocity in the pressure region. C. Normalization of the flow during inspiration. D. Low-resistance hepatic artery flow. E. Normalization of the hepatic artery flow during inspiration. F. Low-resistance flow in the splenic artery. G. Normalization of the splenic artery flow during inspiration

Technical aspects of the examination

Correct preparation for the examination is essential for the analysis of the measured velocity levels. Any food intake can significantly alter the flows in both – the celiac trunk, and the mesenteric arteries. In the case of the celiac trunk a varying increase in the flow rate can be observed; in the case of the mesenteric arteries, a clearly observed increase in flow velocity is complemented by a reduction in the flow resistance (which is caused by the increase – by a factor of 2 or more – in end-diastolic velocity, EDV). Due to the differences between individuals’ responses to food, the current guidelines do not recommend comparing flow velocities before and after a meal(2).

When assessing the arcuate ligament syndrome, it is essential to perform the examination with the patient breathing freely. The probe should be positioned over the celiac trunk, and – when the patient exhales – the recording should be performed. This is not a problem in the triplex mode; however, in a situation where the equipment does not allow for live high-speed measurements, the probe must be placed (and the angle set) in the correct position in the B-mode with color coding, and then the Doppler mode should be enabled, thus freezing the B-frame image, and making minor adjustments in the position of the probe without changing the image controls.

Normal images

Due to changes in the flow velocity caused by the consumption of food, measurements must be performed with patients remaining on an empty stomach. In the case of celiac trunk – in the absence of pressure – the artery is usually straight, and the aorta joint lies at an angle greater than 30°, leading to normal images being registered.

Beyond its initial, curved segment in the middle-upper part, the superior mesenteric artery runs parallel to the front wall of the aorta, causing difficulties in obtaining adequate recording angle not exceeding 60°. In most cases, in order to record images that can be properly assessed, a stronger pressure and deflection of the probe is necessary.

The inferior mesenteric artery normally is a thin vessel, sometimes difficult to visualize; in the absence of pathological changes in the other two arteries it does not require a more detailed assessment.

According to the literature review, the normal levels of flow velocities in visceral vessels are as follows(3):

celiac trunk: PSV – 98–105 cm/s;

SMA: PSV – 97–142 cm/s;

IMA: PSV – 93–189 cm/s.

Based on the observations of the celiac trunk performed by the authors on young, slim patients without the arcuate ligament syndrome, PSV can reach levels up to 150 cm/s.

With age, the visceral vessels flow velocity decreases. It should be noted that any comorbidities may affect the flow in the visceral vessels. In the case of the celiac trunk, this means mainly post-inflammatory cirrhosis with reduced portal flow and a compensatory increase in hepatic and splenic arteries (caused by splenomegaly). Most pathological changes occurring with strongly pronounced splenomegaly (above 15 cm) and hypersplenism cause a marked increase in splenic artery (sometimes reaching more than 2 l/min), significantly altering the flow in the celiac trunk. A similar effect is observed in the case of increasing the flow in the hepatic artery in patients with vascularized metastases to the liver.

Assessment of pathological changes

Due to the numerous connections between the visceral vessels, patients may not show signs of organ ischemia despite the presence of significant stenosis. Generally it is considered that in order for the pathological changes to occur, the narrowing of at least two of the three vessels must take place(4); this assertion, however, constitutes a considerable simplification of a (quite often very complex) clinical problem(5).

It should also be noted that chronic mesenteric ischemia caused by atherosclerosis usually detectable in the initial section of visceral vessels, is just one of several causes of ischemia. Other causes include: congestion/acute thrombosis, hypotensive shock and sepsis, venous outflow obstruction, and mesenteric vascular thrombosis. In all these cases, ultrasound examination provides negligible diagnostic usefulness.

In contrast, ultrasound examination offers considerable diagnostic value in the assessment of chronic intestinal ischemia caused by atherosclerosis in major vessels of the visceral, as well as in the cases of the median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS).

From the clinical perspective, the possibility of chronic ischemia caused by atherosclerotic narrowing of the visceral vessels should be considered in elderly patients with unexplained abdominal pain and loss of body weight (Fig. 4A, B). Such changes on at least one of the visceral vessels occur in several percent of patients over 65 years of age, and are three times more common in women (Fig. 5A–C).

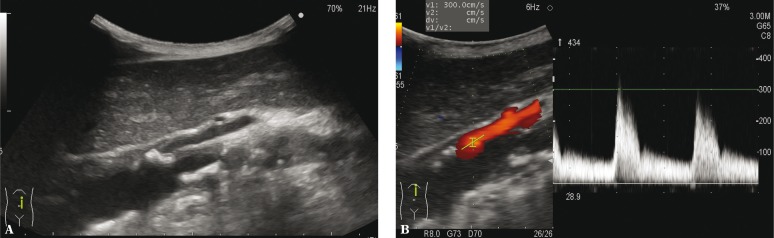

Fig. 4.

A. Atherosclerotic stenosis of the celiac trunk. B. Atherosclerotic stenosis of the celiac trunk – the increase in flow velocity

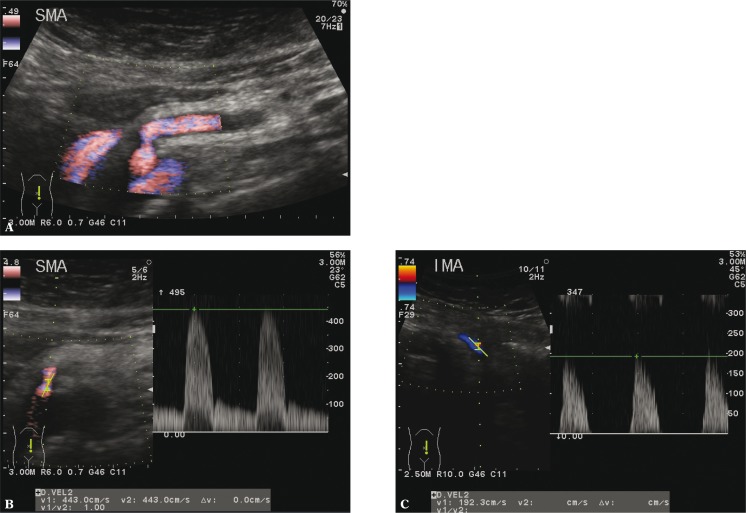

Fig. 5.

A. Superior mesenteric artery stenosis – morphological picture. B. Superior mesenteric artery stenosis – the increase in flow velocity. C. High-resistance flow in the inferior mesenteric artery – narrowing in the distal section

Diagnostics of celiac artery stenosis is based on PSV measurements. The criterion of stenosis of the celiac and superior mesenteric artery exceeding 70% is the increase in peak systolic velocity in the vessels: PSV >200 cm/s for CT, and PSV >275 cm/s for SMA.

According to this criterion, with respect to the visceral trunk, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) are as follows: 75–100%, 87–89% and 85%. A valuable addition to the examination procedure is the evaluation of resistance and pulsatility indices (RI and PI) in the proper hepatic artery and spleen. A decrease in RI below, and in PI below 1.0 are symptoms of significant stenosis. In patients with long-term changes in the developed collateral circulation flow in these vessels (or one of them) the flows may remain unchanged despite celiac trunk stenosis above 80%.

In the case of the superior mesenteric artery, with the flow velocity increasing above 275 cm/s, sensitivity, specificity and PPV are at: 89–100%, 92–100% and 80%.

In the case of IMA, the criterion for hemodynamically significant stenoses (>50%) is the increase in PSV >250 cm/s, with sensitivity and specificity at 90% and 96%, and the overall accuracy of 95%. When the velocity quotient in IMA and aorta is above 4.0, the overall accuracy is 93%(6).

It should also be underscored that a stenosis in one of the visceral vessels will usually increase the flow in other vessels; and whereas the increased flow in the vicinity of stenosis quickly changes to free flow with a distorted spectrum, the compensating increase in flow is visible throughout the entire section being examined.

In the study and diagnostics of visceral vasoconstriction of atherosclerotic it is crucial the flow through these vessels, amounting to about 20% of stroke volume, may double after a heavy meal, and – in contrast – is also subject to double reduction in the cases of pathological changes (shock, hypovolemia) or during a submaximal effort performed on an empty stomach(7).

Occlusion of the lower aorta (Leriche syndrome) is often associated with the occlusion of the IMA.

Morphological evaluation of the degree of stenosis of the celiac trunk in cases where median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) is anticipated involves changes in the shape of the upper section of the vessel, oppressed by a branch of the diaphragm, which sometimes makes it difficult to obtain a proper angle for velocity estimation, mainly due to the widening of the post-stenotic artery compression, within which there are clear turbulence of blood (also recorded in the spectral image).

Morphologically, varying degrees of pressure can be observed in 20–70% of people referred for examination due to abdominal pain, mostly young and slim. In 1% of this group, the occlusion is severe enough to cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting after a meal, and weight loss. The symptoms may occur during and after physical workout. Diagnostic criteria include the increase in PSV above 250 cm/s and EDV >55 cm/s. The velocities drop significantly (often to normal levels) with the examination performed during maximal inspiration(7). The diagnosis may be reached more easily by assessing the flow in the hepatic and splenic arteries – in which changes in RI and PI are visible, reaching levels below 0.65 and 1.0; the increase in resistance and flow rate during inspiration further validates the diagnosis (own material).

It should be noted that the arcuate ligament syndrome is now the leading reason for celiac trunk surgery in the course of chronic ischemia.

Ultrasound examination is also useful in assessing the postoperative state of vascular vessels, also after stenting. In such cases, the criteria for identifying restenosis are: the increase of PSV above 300 cm/s and EDV above 50–70 cm s(8), and – in more severe cases – a decrease in PSV below 40 cm/s (Fig. 6 and 7).

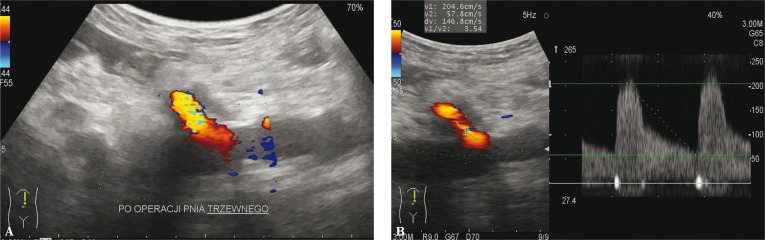

Fig. 6.

A. Celiac trunk after surgical treatment of stenosis – morphological picture. B. Flow velocity in the visceral trunk – borderline values

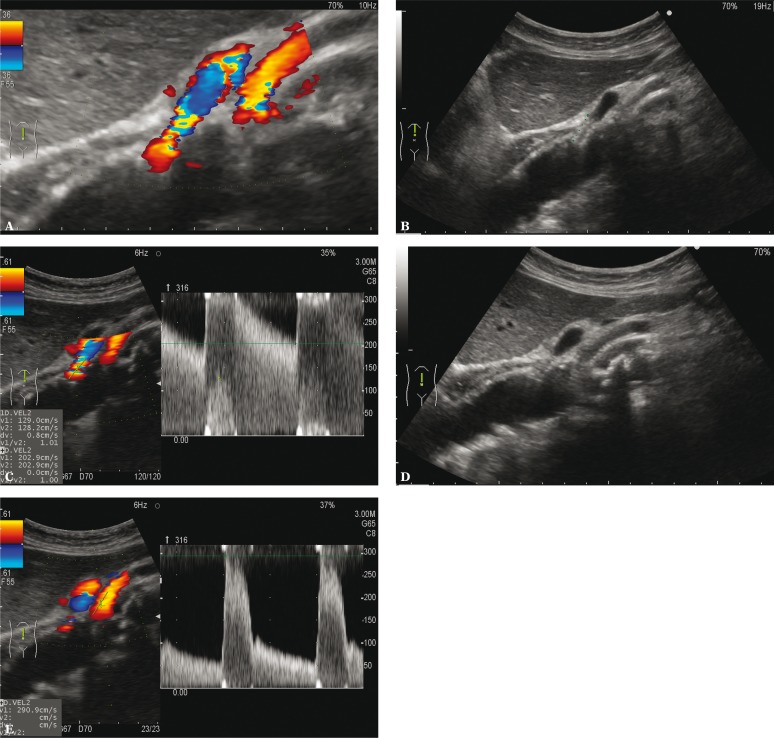

Fig. 7.

A. Celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery after stent implantation. B. Stent implanted in the visceral trunk. C. Pathological increase in the flow velocity in the visceral trunk stent – stenosis. D. Stent implanted in the superior mesenteric artery. E. Flow velocity in the superior mesenteric artery stent – borderline values

Impression

Description of the celiac trunk examination includes morphological assessment of vessel: correct/incorrect diameter with narrowing/post-stenotic widening. Another aspect is the velocity of systolic and diastolic flow in the stenosis during normal breathing and during inspiration. While checking the hepatic and splenic arteries the description should state whether any disorder associated with the current above stenosis occur, including: changes in flow rate, and the reduction of RI.

In the case of atherosclerotic vascular stenosis, the report should also take into account the state of the abdominal aorta, including the size and echogenicity of atherosclerotic plaques, and their relationship to the outgoing vessels.

The description of the mesenteric arteries includes the assessment and recording of flow velocity and possibly an increase/reduction in the flow resistance.

In the case of mesenteric artery stenosis the report impression should evaluate all three visceral vessels. In cases of a narrowing of the celiac trunk is advisable to check the flow in the superior mesenteric artery.

Documentation

Documentation of celiac trunk examination in the absence of pathological changes covers only the recording of blood flow during normal breathing.

In cases when stenosis is identified, the morphological image of the celiac trunk and mesenteric arteries should be recorded, together with the flow spectrum in the point of maximum constriction/pressure with the assessment of velocity during quiet breathing, and during maximum inspiration; and – optionally – with the assessment of flow velocity in the hepatic and splenic arteries during normal respiration and during inspiration. The detection of stenosis in one of the vessels requires the evaluation of others.

In the cases of atherosclerotic, the changes in the abdominal aorta should be recorded.

Summary

Visceral Doppler ultrasound examination enables the evaluation of the hemodynamic significance of stenoses by assessing the changes in blood flow above and below stenosis with distinctive spectrum disorders. This approach is particularly useful in assessing changes associated with compression of the celiac trunk by branches of the diaphragm – the arcuate ligament, as it makes it possible to determine the degree of stenosis, as well as the development of collateral circulation. This allows for rapid implementation of additional diagnostic approaches and therapeutic procedures.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this paper do not claim any financial or personal relationships with other individuals or organizations which could adversely affect the content of this publication, and/or claim any rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Pellerito J, Polak JF. Introduction to vascular sonography. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moneta GL, Taylor DC, Helton WS, Mulholland MW, Strandness DE, Jr, et al. Duplex ultrasound measurement of postprandial intestinal blood flow: effect of meal composition. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1294–1301. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jäger K, Bollinger A, Valli C, Ammann R. Measurements of mesenteric blood flow by duplex scan. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:462–469. doi: 10.1067/mva.1986.avs0030462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxter BT, Pearce H. Diagnosis and surgical management of chronic mesenteric ischemia. In: Strandness DE, van Breda A, editors. Vascular Diseases: Surgical and Interventional Therapy. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cronenwett JL, Johnston KW. Rutherford's Vascular Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellerito JS, Revzin MV, Tsang JC, Greben CR, Naidich JB. Doppler sonographic criteria for the diagnosis of inferior mesenteric artery stenosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:641–650. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronenwett JL, Johnston KW. Rutherford's Vascular Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong PA. Visceral duplex scanning: evaluation before and after artery intervention for chronic mesenteric ischemia. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2007;19:386–392. doi: 10.1177/1531003507311802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]